Robbing Peter to Pay Paul: Ponzi Schemes Throughout History

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul: Ponzi Schemes Throughout History

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul: Ponzi Schemes Throughout History

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

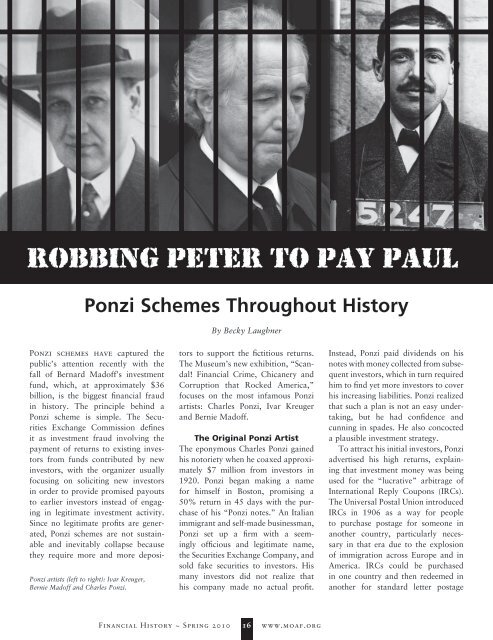

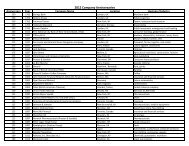

<strong>Robbing</strong> <strong>Peter</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Pay</strong> <strong>Paul</strong><strong>Ponzi</strong> <strong>Schemes</strong> <strong>Throughout</strong> His<strong>to</strong>ryBy Becky Laughner<strong>Ponzi</strong> artists (left <strong>to</strong> right): Ivar Kreuger,Bernie Madoff and Charles <strong>Ponzi</strong>.<strong>Ponzi</strong> schemes have captured thepublic’s attention recently with thefall of Bernard Madoff’s investmentfund, which, at approximately $36billion, is the biggest financial fraudin his<strong>to</strong>ry. The principle behind a<strong>Ponzi</strong> scheme is simple. The SecuritiesExchange Commission definesit as investment fraud involving thepayment of returns <strong>to</strong> existing inves<strong>to</strong>rsfrom funds contributed by newinves<strong>to</strong>rs, with the organizer usuallyfocusing on soliciting new inves<strong>to</strong>rsin order <strong>to</strong> provide promised payouts<strong>to</strong> earlier inves<strong>to</strong>rs instead of engagingin legitimate investment activity.Since no legitimate profits are generated,<strong>Ponzi</strong> schemes are not sustainableand inevitably collapse becausethey require more and more deposi<strong>to</strong>rs<strong>to</strong> support the fictitious returns.The Museum’s new exhibition, “Scandal!Financial Crime, Chicanery andCorruption that Rocked America,”focuses on the most infamous <strong>Ponzi</strong>artists: Charles <strong>Ponzi</strong>, Ivar Kreugerand Bernie Madoff.The Original <strong>Ponzi</strong> ArtistThe eponymous Charles <strong>Ponzi</strong> gainedhis no<strong>to</strong>riety when he coaxed approximately$7 million from inves<strong>to</strong>rs in1920. <strong>Ponzi</strong> began making a namefor himself in Bos<strong>to</strong>n, promising a50% return in 45 days with the purchaseof his “<strong>Ponzi</strong> notes.” An Italianimmigrant and self-made businessman,<strong>Ponzi</strong> set up a firm with a seeminglyofficious and legitimate name,the Securities Exchange Company, andsold fake securities <strong>to</strong> inves<strong>to</strong>rs. Hismany inves<strong>to</strong>rs did not realize thathis company made no actual profit.Instead, <strong>Ponzi</strong> paid dividends on hisnotes with money collected from subsequentinves<strong>to</strong>rs, which in turn requiredhim <strong>to</strong> find yet more inves<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> coverhis increasing liabilities. <strong>Ponzi</strong> realizedthat such a plan is not an easy undertaking,but he had confidence andcunning in spades. He also concocteda plausible investment strategy.To attract his initial inves<strong>to</strong>rs, <strong>Ponzi</strong>advertised his high returns, explainingthat investment money was beingused for the “lucrative” arbitrage ofInternational Reply Coupons (IRCs).The Universal Postal Union introducedIRCs in 1906 as a way for people<strong>to</strong> purchase postage for someone inanother country, particularly necessaryin that era due <strong>to</strong> the explosionof immigration across Europe and inAmerica. IRCs could be purchasedin one country and then redeemed inanother for standard letter postageFinancial His<strong>to</strong>ry ~ Spring 201016www.moaf.org

<strong>to</strong> a foreign country. Although therate of exchange was set by regulations,the devaluation of currenciesacross Europe following World WarI wreaked havoc with rates, creatinga potential arbitrage opportunity.In theory, the trade of InternationalReply Coupons could produce a profit,but there have never been enough couponsin circulation <strong>to</strong> support the scaleof <strong>Ponzi</strong>’s scheme. Most investiga<strong>to</strong>rsnever probed deeply enough <strong>to</strong> realizethat his IRC plan was a hoax, and ifthey attempted <strong>to</strong> do so he claimedhe could not reveal his source for thecoupons for fear that a competi<strong>to</strong>rwould steal his methods. Most of all,his impressive knowledge of the intricaciesof the postal system was enough<strong>to</strong> convince anyone who questionedhis tactics.<strong>Ponzi</strong>’s scheme was eventuallyexposed. The edi<strong>to</strong>rs and reportersof the Bos<strong>to</strong>n Post (now defunct, butwhich won a Pulitzer in 1921 for itscoverage of <strong>Ponzi</strong> and his crimes)became suspicious and brought thescheme <strong>to</strong> the attention of financialreporter Clarence Barron (founderof Barron’s) <strong>to</strong> look in<strong>to</strong> <strong>Ponzi</strong>’soperations. Barron determined that<strong>Ponzi</strong> was most likely a fraud butthe final straw came after the Bos<strong>to</strong>nPost revealed <strong>Ponzi</strong>’s dubious his<strong>to</strong>ryand criminal past in its pages.The news triggered runs by inves<strong>to</strong>rs<strong>to</strong> exchange their notes, causing thescheme <strong>to</strong> unravel. When an audit wasconducted <strong>to</strong> determine how muchmoney had been lost, the final tallywas almost $4 million. Six Bos<strong>to</strong>nbanks were also ruined, and <strong>Ponzi</strong>’sinves<strong>to</strong>rs received only about 30 centson the dollar for their investments.For his crimes, <strong>Ponzi</strong> served almost10 years in federal and state prisonand was eventually deported back<strong>to</strong> Italy. He lived there briefly untilhe got a job through a cousin in theairline industry and moved <strong>to</strong> Brazil.He worked there quite successfullyuntil World War II disrupted the airline’sservice between Italy and Brazil.Despite his innate genius and charismaticpersonality, he spent his life trying<strong>to</strong> get rich quickly and ultimatelydied penniless in Rio de Janeiro in1949 at the age of 67.The Match KingIvar Krueger was known as the “MatchKing” because his fac<strong>to</strong>ries producedmore than two- thirds of the world’smatchsticks at the height of his reignin the 1920s. Although famous for hismatchstick making, Kreuger was actuallya financial genius who masteredseveral industries. Using his experiencein finance, he was able <strong>to</strong> utilizeMuseum of American FinanceS<strong>to</strong>ck certificate for shares in Ivar Kreuger’s company, Kreuger & Toll, dated Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 22, 1931.www.moaf.org 17 Financial His<strong>to</strong>ry ~ Spring 2010

Museum of American FinanceInternational reply coupons like this formed the basis for Charles <strong>Ponzi</strong>’s money-making scheme.creative accounting practices withoutgetting caught, and move moneyaround via off balance sheet liabilitiesand inter-company holdings and raisemassive capital by introducing complexhybrid securities.Kreuger’s life reads like a moviescript. Born in Sweden <strong>to</strong> a familywith a small match fac<strong>to</strong>ry, Kreugeractually got his start in business in theengineering and construction industry.After finishing school in Sweden, heleft for the US <strong>to</strong> make a name forhimself and spent several years floundering,attempting <strong>to</strong> set himself up indifferent regions of the country. EventuallyKreuger got a lucky break thatenabled him <strong>to</strong> pursue engineering. Hespent much of his life as a young adulttraveling the world assisting in majorconstruction projects including thestadium for the 1912 Olympics, theS<strong>to</strong>ckholm city hall, the MetropolitanLife Tower, the Flatiron building, TheMacy’s building, Syracuse University’sstadium and many beautiful hotelsaround the world including the Plazaand St. Regis hotels.After stumbling across “KahnIron,” an innovative new reinforcedconcrete building material used primarilyin America, Kreuger came upwith the idea of introducing it <strong>to</strong>Europe. Partnering with <strong>Paul</strong> Toll, afellow Swede and Kahn’s representativein Europe, the two pioneered newconstruction methods and formed theextremely successful Swedish engineeringfirm Kreuger & Toll. WithKreuger’s business savvy, the companyquickly developed a near-monopoly inconstruction in Europe and Scandinavia.Soon, though, Kreuger set hissights on bigger things and partedways with Toll. Leaving him <strong>to</strong> runthe construction company, Kreugerestablished and ran a spin-off holdingfirm bearing the same name as hisconstruction company.Kreuger began pursuing a differentindustry: matches. Due <strong>to</strong> its abundanceof natural resources, especiallytimber, Sweden had long been a majorplayer in the matchstick market. Beginningwith the takeover of his family’smatch fac<strong>to</strong>ry and then with other fac<strong>to</strong>riesin the region, Kreuger quicklycame <strong>to</strong> dominate the Swedish matchstickindustry. Unlike <strong>Ponzi</strong>, Kreugerproduced actual profits and was quitea successful entrepreneur and financialmanager. It would not be until laterthat Kreuger would begin his scheme.In 1922 Kreuger made a triumphantreturn <strong>to</strong> America <strong>to</strong> court the prominentinvestment bank Lee, Higginson& Co. With his extensive knowledgeand ability <strong>to</strong> recite facts and statisticson even the most arcane financial<strong>to</strong>pics, Kreuger impressed the Lee,Higginson & Company board, anda partnership was formed. Togetherthey introduced numerous securities<strong>to</strong> the American public over the next10 years until Kreuger’s death in 1932.Securities were issued for Kreuger &Toll, International Match and SwedishMatch Company, the largest ofKreuger’s companies, though it isbelieved that Kreuger supervised over400 different corporations worldwide,some of which were legitimate andothers that only existed on paper.Because Kreuger was incrediblysecretive and he alone controlled hisbusinesses, he treated his companiesas one giant corporation and freelymoved funds between them, often<strong>to</strong> the confusion of his accountants.This provided him liquidity and theability <strong>to</strong> pay consistently high dividends,usually 20–25%, even on hisfailed ventures. (One of Kreuger’sunsuccessful endeavors included a tryat the film industry, which he loved.He is credited with discovering GretaGarbo, a fellow Swede and longtimefriend.) Kreuger realized that hecould use the capital raised from InternationalMatch securities <strong>to</strong> negotiateloans <strong>to</strong> foreign governments inexchange for match monopolies. Hethen turned around and used profitsof his monopolies <strong>to</strong> pay returns onhis securities and negotiate the issuanceof new securities. Playing on theincredible confidence US inves<strong>to</strong>rs hadin him, Kreuger would occasionallyissue securities before the negotiationswith national governments for matchmonopolies that funded the securitieswere finalized.Kreuger was remarkable in that heFinancial His<strong>to</strong>ry ~ Spring 201018www.moaf.org

existed as a sort of private financier <strong>to</strong>the world, negotiating complex loanswith governments. He essentiallyachieved what the Dawes Plan didby himself; in a little over a decade,Krueger negotiated loans with matchdeals <strong>to</strong> Peru, Poland, Ecuador, Es<strong>to</strong>nia,France, Greece, Hungary, Latvia,Portugal, Romania, Yugoslavia, Germany,Bolivia, Bulgaria, Guatemala,Lithuania, Turkey and after extensivenegotiations without a resolution, hefabricated a deal with Italy, even forgingthe Minister of Finance’s signatureon fake bonds. He was able <strong>to</strong> coverhis liabilities and support new businessendeavors by collecting fundsfrom new security issues by Kreuger& Toll and its subsidiaries in a giant,complex <strong>Ponzi</strong> scheme.After the Crash of 1929, Kreuger’scompanies appeared <strong>to</strong> weather thes<strong>to</strong>rmy economic climate better thanmost. Not believing that the crashwould continue, Kreuger continuedpaying out false dividends and evenextended his liabilities by negotiatinga $125 million loan <strong>to</strong> Germany.It was impossible <strong>to</strong> raise sufficientfunds in the aftermath of the crash <strong>to</strong>keep up with his obligations. Eventually,Kreuger began <strong>to</strong> falter on hispayments. Realizing he would soonbe discovered, he committed suicide inMarch 1932. A financial crisis ensuedalmost immediately after Kreuger’sdeath, but it would not be for anothercouple of years that the full extent ofhis deception would be known.Bernard MadoffIn 2008, the largest <strong>Ponzi</strong> schemein his<strong>to</strong>ry was revealed by the mastermindbehind it: Bernard Madoff.Unlike <strong>Ponzi</strong> and Kreuger’s pasts,Madoff’s background provided noindication of his capacity <strong>to</strong> commitfraud. A co-founder and former chairmanof NASDAQ, he served on theboard of the National Associationof Securities Dealers, was active inphilanthropic circles, and his firm wasat one time the largest market-makerin NASDAQ securities. Founded in1960, Bernard L. Madoff InvestmentSecurities LLC was mostly known formarket making and acting as the middleman in the transaction of buyingand selling s<strong>to</strong>cks. He was a pillar inthe securities industry, providing solidadvice for almost 50 years. Whenhe turned himself in, he caught theworld off-guard, including the SecuritiesExchange Commission.It is estimated that Madoff’s fraudbegan sometime in the 1980s or early1990s, meaning he collected between$10–17 billion in bogus investmentsin only 20 years. Estimated losseswith fabricated gains are thought <strong>to</strong>be approximately $65 billion. Thereare many similarities between <strong>Ponzi</strong>,Kreuger and Madoff’s schemes. LikeKreuger, Madoff’s legitimate activitiesacted as a cover for his fraudulentdealings. Madoff oversaw a secretive,guarded arm of his renowned firmthat provided wealth management services.Keeping it separate from the res<strong>to</strong>f his business, even physically segregatingit on another building floorfrom the rest of his operations, it wasunder this secret division that Madoffran a <strong>Ponzi</strong> scheme with money fromhis wealthier clients. Madoff did no<strong>to</strong>penly advertise his special privatewealth management services, creatingthe illusion of exclusivity. The fundconsistently paid out a steady returnof 12% (less ostentatious than <strong>Ponzi</strong>’s50% or Kreuger’s 20–25%). Oncegranted the privileges of investingwith Madoff’s fund, deposi<strong>to</strong>rs werereluctant <strong>to</strong> question the details of hismethods or strategy.As a well-respected financial manager,a man who had testified beforeCongress and who had also workedalongside the SEC in the regulation ofNASDAQ in its early days, the SECfound it unnecessary <strong>to</strong> interrogate hisoperations as well. His swindle wasnot actually discovered until he turnedhimself in, revealing everything andtaking sole credit for the entire scheme.It is curious that a serious investigationwas never made. In hindsight, thesigns are all there and we know thata handful of people had picked upon the suspicious nature of Madoff’sprofits. In May 2001, both Barron’sand a trade publication called Mar/Hedge published investigative reportson his hedge fund, both citing theimpossible annual returns, Madoff’sdecision <strong>to</strong> charge a paltry commissioninstead of collecting management fees,and Mar/Hedge additionally noted theunlikelihood of Madoff’s hedge fundbeing one of the largest in the worldwhile remaining virtually unknown.Harry Markopolos also vociferouslyproclaimed Madoff <strong>to</strong> be a fraud,picking up on suspicious behavior asearly as 1999 and even reported hismisgivings <strong>to</strong> the SEC on more thanone occasion.At age 71, Madoff went <strong>to</strong> trial andpled guilty <strong>to</strong> 11 federal offenses, possiblysparing his family and those aroundhim from admitting responsibility. Hewas sentenced <strong>to</strong> 150 years in prison,the maximum allowable sentence withno possibility for parole.None of these three s<strong>to</strong>ries havehappy endings. Between severe prisonsentences and death, each financierpaid duly for their crimes. Even if theybelieved their schemes were only atemporary means <strong>to</strong> an end, they allultimately proved that fraud does notpay (for very long) and that a Rob-<strong>Peter</strong>-<strong>to</strong>-<strong>Pay</strong>-<strong>Paul</strong> scheme is never sustainable.Despite these three examples,which vividly illustrate this importantlesson, <strong>Ponzi</strong> artists continue <strong>to</strong> practicetheir art. Just as Kreuger ignored<strong>Ponzi</strong>’s fate and Madoff disregardedthem both, small scale <strong>Ponzi</strong> schemesare still amazingly still being revealedeven with Madoff’s name still in newspaperheadlines. FHBecky Laughner is the Museum’sAssistant Direc<strong>to</strong>r of Exhibits andArchives.www.moaf.org 19 Financial His<strong>to</strong>ry ~ Spring 2010