Alexander Hamilton Central Banker and Financial Crisis Manager

Alexander Hamilton Central Banker and Financial Crisis Manager

Alexander Hamilton Central Banker and Financial Crisis Manager

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

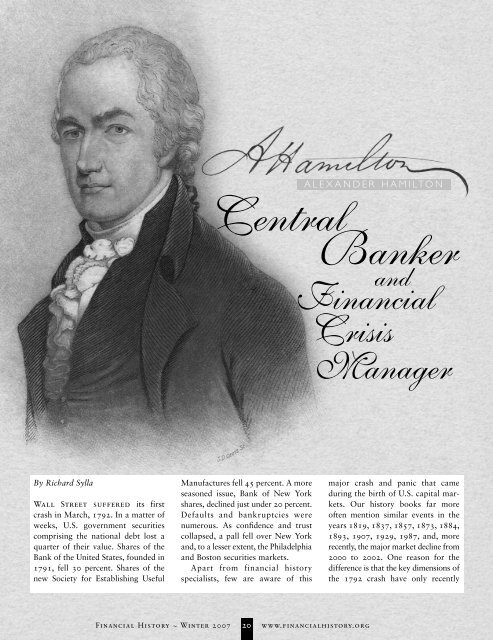

ALEXANDER HAMILTON<strong>Central</strong><strong>Banker</strong><strong>and</strong><strong>Financial</strong><strong>Crisis</strong><strong>Manager</strong>By Richard SyllaWall Street suffered its firstcrash in March, 1792. In a matter ofweeks, U.S. government securitiescomprising the national debt lost aquarter of their value. Shares of theBank of the United States, founded in1791, fell 30 percent. Shares of thenew Society for Establishing UsefulManufactures fell 45 percent. A moreseasoned issue, Bank of New Yorkshares, declined just under 20 percent.Defaults <strong>and</strong> bankruptcies werenumerous. As confidence <strong>and</strong> trustcollapsed, a pall fell over New York<strong>and</strong>, to a lesser extent, the Philadelphia<strong>and</strong> Boston securities markets.Apart from financial historyspecialists, few are aware of thismajor crash <strong>and</strong> panic that cameduring the birth of U.S. capital markets.Our history books far moreoften mention similar events in theyears 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1884,1893, 1907, 1929, 1987, <strong>and</strong>, morerecently, the major market decline from2000 to 2002. One reason for thedifference is that the key dimensions ofthe 1792 crash have only recently<strong>Financial</strong> History ~ Winter 200720www.financialhistory.org

Collection of the Museum of American FinanceCertificate for stock in the Bank of the U.S., January 20, 1792.been recovered. The price changesmentioned in the previous paragraphare part of a new securities pricedatabase compiled, mostly from oldnewspapers, by Jack W. Wilson,Robert E. Wright, <strong>and</strong> me.A more important reason why1792 is less than memorable is thatit had no discernable economic consequences.There was no recession,much less a depression. Prices stoppedfalling by mid-April, the U.S. economycontinued to grow vigorously as it hadsince 1789, <strong>and</strong> the events of Marchwere soon forgotten. But why? Wasthis just an early example of thatDivine Providence that is said to lookafter fools, drunks, <strong>and</strong> the UnitedStates of America?No. Potentially damaging economicconsequences of the panic wereavoided, it is now quite clear, by verymodern central-bank-like interventionsorchestrated by <strong>Alex<strong>and</strong>er</strong> <strong>Hamilton</strong>.<strong>Hamilton</strong>, Secretary of the Treasury,at the time was executing his gr<strong>and</strong>plan to give the country a modern,state-of-the-art financial system.<strong>Hamilton</strong>, who knew his financialhistory, was well aware that a disastrouspanic could defeat the plan.He had studied the 1720 collapseof John Law’s Mississippi Bubble inFrance, which weakened Francefor decades, <strong>and</strong> the related collapsethat same year of the South SeaBubble, which had somewhat lessdamaging consequences for Engl<strong>and</strong>’sfinancial system.Trial Run: The 1791Bank Script BubbleIn 1791, during the crash of a bubbleconnected with scripts — rights tobuy full shares — issued in the IPO ofthe Bank of the United States (BUS),<strong>Hamilton</strong> wrote Senator Rufus Kingthat “a bubble connected with myoperations is of all the enemies Ihave to fear, in my judgment themost formidable.” So <strong>Hamilton</strong> thendirected open market purchases ofgovernment debt to inject liquidityinto panicky markets. It proved tobe a test run for a wider range ofinterventions in the more seriouscrash of 1792.Bank scripts were issued on July 4,1791. For a $25 down-payment, aninvestor received a script entitling theholder to purchase of a full BUS shareafter a series of further payments of$375. Scripts doubled in price in July,<strong>and</strong> then really took off, reachingprices of $264 (New York) to $300(Philadelphia) on August 11. Thewww.financialhistory.org 21 <strong>Financial</strong> History ~ Winter 2007

Three checks from the Bank of the U.S. dated the year of the panic, 1792.dotcom bubble of recent memorywas hardly new or unique.In the following days <strong>and</strong> weeksscripts lost more than half of theirpeak valuations — the bid price was110 in New York on September 9 —dragging down with them prices ofU.S. debt securities. Sensing trouble,<strong>Hamilton</strong> on August 15 sprang intoaction. He convened a meeting of thecommissioners of the Sinking Fund(himself <strong>and</strong> four other top officialsof the federal government) <strong>and</strong> persuadedthem to authorize open marketpurchases of $300–400 thous<strong>and</strong> ofU.S. debt at Philadelphia <strong>and</strong> NewYork. The Sinking Fund was a feature<strong>Hamilton</strong> had included in his 1790national debt restructuring plan,ostensibly to assure investors that theU.S. government was committed topaying down its debt, but really —since it would be some time beforefederal revenues would allow anypay-down — to allow just such shorttermopen-market interventions. TheCollection of the Museum of American Financepurchases were financed by loansfrom banks.Over the next month, mid-Augustto mid-September, Sinking Fundrecords show the Treasury purchasing$150 thous<strong>and</strong> of U.S. debt inPhiladelphia <strong>and</strong> $200 thous<strong>and</strong> inNew York, where the money was borrowedfrom the Bank of New York<strong>and</strong> the purchases were executed bythe bank’s cashier, William Seton. TheBUS, the national bank, had just hadits IPO <strong>and</strong> would not open for businessin Philadelphia until December, <strong>and</strong>would not have a New York branchuntil April 1792. <strong>Hamilton</strong> thereforehad to work through the one bankthen in New York, <strong>and</strong> it probablyhelped that he had been one of itsfounders in 1784.By having the Sinking Fund purchaseabout two percent of the debtoutst<strong>and</strong>ing in 1791, <strong>Hamilton</strong> hadnipped in the bud an incipient marketcrash. The liquidity injection calmedthe markets. From New York, Setonin September wrote <strong>Hamilton</strong> inPhiladelphia, saying, “You have theblessings of thous<strong>and</strong>s here, <strong>and</strong> I feelgratified more than I can express, atbeing the dispenser of your benevolence.”Markets are grateful to centralbankers who intervene to prevent pricesfrom collapsing by buying wheneveryone else wants to sell.Causes of the 1792 PanicTraditional accounts of rapid run upof securities prices in the first twomonths of 1792, followed by thecrash of prices in March <strong>and</strong> April,blame it on an ill-fated plan of acabal of New York speculators led byWilliam Duer to corner the marketfor U.S. six percent bonds (6s). Under<strong>Hamilton</strong>’s plan for capitalizing theBUS, investors holding Bank scriptscould pay three-fourths of the fullshare price, $400, by tendering 6s.Duer <strong>and</strong> his associates plotted toborrow whatever money they could,often by offering very high rates of<strong>Financial</strong> History ~ Winter 200722www.financialhistory.org

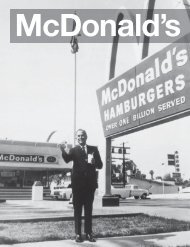

$50 promissory note from the Bank of the U.S. issued August 1, 1792.interest, to buy up most of the 6s, <strong>and</strong>then sell at high prices to those whoneeded 6s to purchase Bank shares in1792 <strong>and</strong> 1793. As the plot wasimplemented, 6s rose from 110 (percentof par) in late December 1791 to125 by mid January 1792, to a peakof 126.25 in early March. But onMarch 9 Duer defaulted on his debts,triggering a chain of further defaults<strong>and</strong> liquidations that drove 6s downto a low of 95 on March 20. Governmentsecurities had lost a quarter oftheir value in about two weeks.More recent research confirmsthat another factor besides the Duercabal was at work in early 1792 todrive up prices <strong>and</strong> then drive themdown. Price bubbles are almost alwaysfueled by newly-created credit, <strong>and</strong> ithappened that a new <strong>and</strong> large sourceof such credit became available at theend of 1791, namely the Bank of theUnited States. The Bank opened inPhiladelphia in December 1791, <strong>and</strong> bythe end of January 1792 it had issued$2.2 million of notes <strong>and</strong> deposits(monetary liabilities) while discountingloan paper of $2.7 million. Some ofthose loans found their way to Duer<strong>and</strong> other speculators.The new central bank had beencareless with its credit creation inits first weeks <strong>and</strong> months. By earlyFebruary, holders of BUS notes <strong>and</strong>deposits were redeeming them forspecie reserves, which fell from $706thous<strong>and</strong> on December 29, to $510thous<strong>and</strong> on January, to $244 thous<strong>and</strong>on March 9. It was a classic drainof reserves from a bank that hadexp<strong>and</strong>ed credit too fast <strong>and</strong> too far.In February, <strong>Hamilton</strong> had to informthe Bank of New York, which itselfwas stressed, that the Treasury wouldhave to draw funds from it to propup the BUS in Philadelphia. At thesame time he urged all banks to reducetheir lending “gradually.” Instead, thebanks stepped hard on the brakes;BUS discounts, for example, declinednearly 25 percent from January 31 toMarch 9, the very day William Duerdefaulted on his debts. Duer nodoubt was a reckless speculator <strong>and</strong>plunger. But in the end he <strong>and</strong> otherslike him were done in by an abrupttightening up of bank credit.<strong>Hamilton</strong> Manages the <strong>Crisis</strong>On March 19, the day before U.S. 6sreached their panic low of 95 in NewYork, <strong>Hamilton</strong> initiated a numberof actions to alleviate the financialdistress. First, he asked the nation’sbanks, still few in number, to lendmoney to merchants who owed customsduties to the Treasury. Hepromised the banks that the Treasurywould not draw the money fromthem for three months.Second, <strong>Hamilton</strong> reminded theTreasury’s collectors of customs inthe nation’s port cities that they wereauthorized to receive post-notes ofthe BUS maturing in 30 days or less“upon equal terms with cash,” <strong>and</strong>he encouraged the BUS to issue suchMuseum of American Financepost-notes as a way of temporarilyconserving its specie reserves.Third, <strong>Hamilton</strong> had the Treasurymake open market purchases atPhiladelphia, using the funds authorizedto be spent by the Sinking Fundin 1791 that had not been expendedthen. And he called the Sinking Fundcommissioners to meet on March 21to authorize more open market purchasesof U.S. debt. There were somedelays in getting the authorizations,but over the next month <strong>Hamilton</strong>directed agents in Philadelphia <strong>and</strong>New York to purchase on the openmarket nearly $250 thous<strong>and</strong> worthof U.S. debt to inject liquidity to thepanicked securities markets.Fourth, <strong>Hamilton</strong> learned in Marchthat the U.S. minister in Amsterdamhad arranged a loan to the Treasuryfrom Dutch bankers of three millionflorins ($1.2 million) at four percentinterest. He directed his agents inU.S. markets to publicize news of theloan, to assure panicky investors thatU.S. finances were in strong shape.Fifth, <strong>Hamilton</strong> initiated a planamong the banks, merchants, <strong>and</strong>securities dealers in New York tocooperate in stemming the crisis. In aletter of March 22 (which becamepublic only in 2005), <strong>Hamilton</strong> suggestedto Seton at the Bank of NewYork that rather than dump theirholdings on the market to meet liquidityneeds, which would only exacerbatethe crisis, the merchants <strong>and</strong>dealers instead use up to $1 million ofU.S. securities at values specified by<strong>Hamilton</strong> as collateral for credits atthe bank. The dealers <strong>and</strong> merchantscould then write checks against thesecredits to settle their accounts withone another, avoiding panic liquidation.Anticipating what decades laterwould be called Bagehot’s rules forproper central bank behavior in acrisis, <strong>Hamilton</strong> directed that theloans be made at the high discountrate of seven percent instead of theusual six percent. Walter Bagehot, awww.financialhistory.org 23 <strong>Financial</strong> History ~ Winter 2007

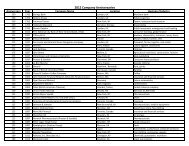

U.S. Sixes, Philadelphia Price130120110Bi d P r i ce ( P e rcent o f Pa r )100908070601790.10301790.11241790.12151791.01051791.0129179. 0Date1 2191791.03231791.04131791.05071791.06011791.06251791.07161791.08101791.09031791.09281791.10221791.11121791.12071791.12311792.01211792.02151792.03141792.04071792.05051792.06021792.06271792.07211792.08111792.08291792.09291792.10241792.11171792.1208student of English central banking,publicized his rules in his book LombardStreet in 1873. The rules in essencesaid that a central bank in a crisisshould lend freely on good collateral,such as government securities, but ata high rate of interest so borrowerswould have an incentive to repay theloans as soon as the crisis had passed.<strong>Hamilton</strong>’s creative financial mindhad come up with Bagehot’s rulesnine decades before Bagehot.But what if the crisis did not end<strong>and</strong> the Bank of New York got stuckwith collateral that had fallen in value.<strong>Hamilton</strong> deemed that possibility“not supposeable,” but to alleviateconcerns on the part of the bank, heoffered to repurchase from it up to$500 thous<strong>and</strong>, again at the values<strong>Hamilton</strong> had specified. In other words,<strong>Hamilton</strong> combined a repurchaseagreement with Bagehot’s rules.The plan was implemented. Fivedays later, an agent of <strong>Hamilton</strong>’s inNew York wrote to him to report,“The dealers last night had a meeting& appointed a committee, to conferwith the directors of the two banks[Bank of New York, <strong>and</strong> the BUSNew York branch about to open inApril]. The propositions they are tohold out I hear in general is to offer,funded debt, at your price [emphasisadded] as pledges for their discounts– & they are to sign an agreement tobind themselves not to draw anyspecie from the banks, on account ofthe discounts they shall obtain <strong>and</strong>giving checks to each other…”Together the combined effect of<strong>Hamilton</strong>’s crisis management measuresworked. By mid-April, the Panicof 1792, Wall Street’s first crash, wasover <strong>and</strong> the securities marketsreturned to routine trading activities.Despite many bankruptcies, therewere virtually no negative effects onthe U.S. economy. It continued to growat higher rates than were commonbefore the financial reforms that beganin 1789.In the aftermath of the panic, 24brokers <strong>and</strong> dealers met in Mayunder a buttonwood tree on Wall Street,<strong>and</strong> subscribed to an agreement thatis regarded as the origin of the NewYork Stock Exchange. Ten of the 24had sold securities to the Treasury inthe open market purchases of March<strong>and</strong> April. So it is possible that thespirit of cooperation in the financialcommunity <strong>Hamilton</strong> encouraged duringthe panic carried over when WallStreet moved toward an improvedtrading system in May.There was political fallout fromthe 1792 panic. The crisis appearedto confirm in the minds of leaderssuch as Jefferson <strong>and</strong> Madison that<strong>Hamilton</strong>’s financial program wasturning the United States into anation of paper speculators <strong>and</strong>stockjobbers rather like Engl<strong>and</strong>,instead of the nation of virtuous<strong>Financial</strong> History ~ Winter 200724www.financialhistory.org

Dr. Richard Sylla is Henry KaufmanProfessor of the History of <strong>Financial</strong>Institutions <strong>and</strong> Markets at NewYork University’s Stern School ofBusiness, <strong>and</strong> a trustee of theMuseum of American Finance.SourcesCowen, David J. The Origins <strong>and</strong> EconomicImpact of the First Bank of theUnited States, 1791-1797. New York& London: Garl<strong>and</strong>, 2000.<strong>Alex<strong>and</strong>er</strong> <strong>Hamilton</strong>, first Secretary of the Treasury,also acted as the nation’s first central banker during the Crash of 1792.Republican farmers they hoped for.Jefferson <strong>and</strong> Madison redoubled theirefforts in opposition to <strong>Hamilton</strong>’smeasures. Thus, the panic encouragedthe formation of a two-party systemof politics <strong>and</strong> government that wasemerging in those early years, largelyas a consequence of <strong>Hamilton</strong>’sfinancial program.<strong>Hamilton</strong> as <strong>Central</strong> <strong>Banker</strong>We usually think of <strong>Alex<strong>and</strong>er</strong> <strong>Hamilton</strong>as the country’s first Secretary ofthe Treasury who successfully stabilizedthe new federal government’s initiallyshaky finances. We also know that hewas quite a soldier, lawyer, constitutionalist,<strong>and</strong> political essayist —among other things, he conceived ofthe Federalist Papers project <strong>and</strong>wrote three-fifths of the 85 Federalistessays. We know that he conceived<strong>and</strong> founded the BUS, the nation’sfirst central bank, but that he left themanagement of it to others. In 1791<strong>and</strong> 1792, however, when the BUS —<strong>and</strong> indeed, the entire U.S. financialsystem — was new <strong>and</strong> inexperienced,it is clear that <strong>Hamilton</strong> acted as acentral banker <strong>and</strong> crisis manager.Thus, as we approach the 250th(or some say, 252nd) anniversary of<strong>Hamilton</strong>’s birth on January 11, 2007,we can add another feather to <strong>Hamilton</strong>’scap. He was one of the very firstcentral-bank-like managers of afinancial crisis. As in so many otherareas of his endeavors, despite havingfew precedents to guide him, as acentral banker <strong>Hamilton</strong> acquittedhimself quite well. FHCollection of the Museum of American FinanceCowen, David J., Richard Sylla, <strong>and</strong>Robert E. Wright. “The U.S. Panicof 1792: <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Crisis</strong> Management<strong>and</strong> the Lender of LastResort.” Working Paper, SternSchool of Business, New York University,October 2006.Davis, Joseph S. “William Duer, Entrepreneur,1747-99.” In Davis, Essayson the Earlier History of AmericanCorporations. Cambridge: HarvardUniversity Press, 1917, pp. 111-348.Downing, Ned W. “Transatlantic Paper<strong>and</strong> the Emergence of the AmericanCapital Market.” In The Origins ofValue: The <strong>Financial</strong> Innovations thatCreated Modern Capital Markets, W.N. Goetzmann <strong>and</strong> K.G. Rouwenhorst,eds. Oxford <strong>and</strong> New York:Oxford University Press, 2005, chap.16, pp. 271-98.<strong>Hamilton</strong>, <strong>Alex<strong>and</strong>er</strong>. The Papers of<strong>Alex<strong>and</strong>er</strong> <strong>Hamilton</strong>, Harold Syrett,ed. New York: Columbia UniversityPress, 1961-87. Vols. IX-XI.Sylla, Richard. “The Origins of the NewYork Stock Exchange.” In The Originsof Value: The <strong>Financial</strong> Innovationsthat Created Modern CapitalMarkets, W. N. Goetzmann <strong>and</strong> K.G.Rouwenhorst, eds. Oxford <strong>and</strong> NewYork: Oxford University Press, 2005,chap. 17, pp. 299-312.Wright, Robert E., <strong>and</strong> David J. Cowen.<strong>Financial</strong> Founding Fathers: The MenWho Made America Rich. Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 2006.www.financialhistory.org 25 <strong>Financial</strong> History ~ Winter 2007