Download - Acton Institute

Download - Acton Institute

Download - Acton Institute

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

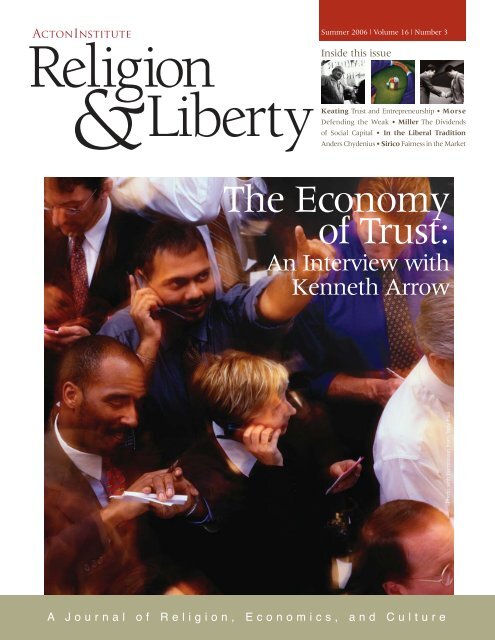

Religion&LibertySummer 2006 | Volume 16 | Number 3Inside this issueKeating Trust and Entrepreneurship • MorseDefending the Weak • Miller The Dividendsof Social Capital • In the Liberal TraditionAnders Chydenius • Sirico Fairness in the MarketThe Economyof Trust:An Interview withKenneth ArrowPhoto:with permission from Tony HallAJournal of Religion, Economics, and Culture

Editor’s NoteDo you have to be good to do well? Therelationship between virtue and worldlysuccess is one that is often discussed atour <strong>Acton</strong> events. Parents and teacherstry to inculcate good habits in their childrenand students, not only as an end initself, but also in the hope that doinggood in the spheres of character andmorality will lead to doing well in theworlds of work, entrepreneurship, andcommerce.In this issue of Religion & Liberty, we takelook at that question from various pointsof view. Our biblical feature examinesEditorial BoardPublisher: Rev. Robert A. SiricoExecutive Editor: John CouretasEditor: Rev. Raymond J. de SouzaManaging Editor: David Michael PhelpsTypesetting and Layout: Leslie YarhouseThe <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> for the Study of Religion and Liberty promotes a free societycharacterized by individual liberty and sustained by religious principles.Letters and requests should be directed to: Religion & Liberty; <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong>;161 Ottawa Ave., NW, Suite 301; Grand Rapids, MI 49503. For archived issuesor to subscribe, please visit www.acton.org/publicat/randl.The views of the authors expressed in Religion & Liberty are not necessarilythose of the <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong>.the teaching about weights and measuresin the Gospel. Being honest inmeasurement is the right thing to do initself, but it also makes possible easytrade and free exchange; imagine theimpossibility of having to verify thatevery package contains the indicatedweight of flour, or sugar, or salt. Our“Double-Edged Sword” this issue comesfrom Rolf Geyling’s submission to the<strong>Acton</strong> homiletics contest.ContentsFrom the perspective of economics, notScripture, we address some of thesesame questions with Professor KennethArrow in our interview. For me, as a onetime graduate economics student whoread Professor Arrow’s work, it was athrill to interview him—and an honorfor R&L to have a Nobel laureate in ourpages. Professor Arrow shows how theexistence of markets at all, let alone theirefficient functioning, depends upon afundamental honesty and trust amongstbuyers and sellers. The market needsmorality. And does the market encourageor discourage the morality it dependsupon? I’ll let you read ProfessorArrow’s answer for yourself.Our own Michael Miller, <strong>Acton</strong>’s directorof programs, takes up the same questionby revisiting an important bookby Francis Fukuyama on the role of “socialcapital” in economic development.Fukuyama’s book is not new, but his argumentremains novel and important:Without trust, markets don’t work well.And finally, I might draw your attentionto our review of John C. Maxwell’s bookThere’s No Such Thing as “Business” Ethics.Maxwell is one of the more popular authorsin the field of business ethicswhich, judging by the number of new titlesin the bookstores, is a booming market.He makes the argument that ethicsin business is not terribly different fromordinary ethics in everyday life. Doinggood is just plain good—for our souls,and for the economy.The Economy of Trust: Kenneth Arrow..................................3Trust and Entrepreneurship: Raymond J. Keating.............4Second-Career Clergy and Parish Business: An Interviewwith Jonathan Englert.......................................................................6<strong>Acton</strong> FAQ ...............................................................................7The Dividends of Social Capital: Michael Miller...................8Double-Edged Sword ...........................................................9Defending the Weak and the Idol of Equality: JenniferRoback Morse.......................................................................10In the Liberal Tradition: Anders Chydenius.......................14Column: Rev. Robert A. Sirico................................................15Book Review.........................................................................16© 2006 <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> for the Study of Religion and Liberty.2 Religion&Liberty

The Economy of TrustAn Interview with Kenneth ArrowKenneth ArrowKenneth Arrow of Stanford won the NobelMemorial Prize for Economics in 1972,and has served as president of both theAmerican Economic Association and theInternational Economic Association. In2004, he was awarded the National Medalfor Science, the United States’ highestaward for scientific achievement. A pioneerin the fields of social choice and welfareeconomics, Professor Arrow has alsowritten in the fields of philosophy andethics. He was invited to participate in thepreliminary consultations during the draftingof Centesimus Annus, and later the PontificalAcademy of Social Sciences. He recentlyspoke with our editor, Father deSouza, in Rome._____________________________________What can the world of religion and ethics contributeto economics?The market has deficiencies of a kind forwhich ethics is a remedy. For example, theworld is really filled with private information.There is inside information on productsand in contracts. In these situations,there is a very strong possibility of one personusing this information to take advantageof the other. If this happens frequently,a market may not exist at all becausethe buyers know that they don’t knowcertain things, and that the sellers can exploitthem. Therefore, it’s not so much thatthere are potential unfair gains, but thatsuch uncertainties about private informationcan make the market inefficient. Infact, if the problem is pronounced, themarket may not exist at all. This is a situationthat is studied particularly in insurancecontracts; when the person insuredmay have private information about dangersunknown to the insurer, there is saidto be “moral hazard” or “adverse selection,”phrases in the last forty years thathave been imported into economic analysisfrom insurance literature.There are various ways of handling thesecases. One of them is the existence ofmorality. It turns out that to a considerableextent, people spontaneously do avoidtaking excessive advantage of their insideinformation, their private information.Part of it is an understanding that eventhough I would gain by cheating, it wouldbring down the market if everybody did it.Of course, there can be a problem if oneperson says, “Well, if I did it, nobody willnotice.” But then, if each person feels thesame way the whole thing breaks down.Part of this behavior, though, is morality—the person doesn’t cheat because he thinksit’s the wrong thing to do. To get marketsthat work, you have to keep the other personfrom trying to cheat you at every moment.So morality is closely related to theworkings of the market.The other point, of course, is that peopledo have aims in life, and not just the grandachievement of material gains. They’reconcerned about others. This concern isthe result of moral codes, which are developedand adopted through religion orthrough inculcation by other ethicalsources. Certainly family relationships aremarked by sacrifice. People are engaged inthese relationships, and therefore, they devotetheir energies to acquire goods, notfor the purpose of using them themselves,but for others.So there are two aspects to this relationship.One relates to deep concern for others,and therefore touches upon the endsof economic activity. The other relates tothe means of economic activity—the market.Morality plays a functional role in theoperation of the economic system.“To get markets thatwork, you have tokeep the other personfrom trying to cheatyou at every moment.So morality is closelyrelated to the workingsof the market.”Could it be argued that a certain amount ofvirtue of a basic kind—being honest, honoringcontracts, providing accurate information—isrequired for a market to work? Is it a dangerthat prosperity can sometimes weaken thosevirtues? To become prosperous you need to bevirtuous, but then does prosperity erode thefoundations of virtue?I don’t know if it’s so much prosperity asthe prospect of prosperity that’s dangerous.When you see a large potential personalgain, you may tend to feel that yourvirtue stands in the way. Now there is alwaysthe question of whether you can getaway with something or can cut corners.You may find the pursuit of the materialgoods becomes an end in itself. But ifyou’re a chess nut, you can also be a facontinuedon pg 12Summer 2006 2005 | Volume 16 15 | Number 313

Getty ImagesTrust andEntrepreneurshipby Raymond J. KeatingWhen it comes to business and the economy,the word trust has two—and to somepeople diametrically opposed—meanings.Trust as a virtue in the marketplace meanshaving confidence in the honesty, reliability,and integrity of market players. Itspeaks volumes about our free enterprisesystem that a stranger can walk into asmall business, for example, that he hasnever patronized before, and yet generallytrust that he will be served well, dealt withfairly, and will walk out the door with aproduct that does what it is supposed to do.But trust also refers to a business organizationwhereby a group of trustees controlone or more corporations. Trusts emergedin the latter half of the nineteenth century,and were accused of assorted marketabuses, with antitrust laws emerging in response.Ironically, trusts came to signify, inpopular terms at least, big bad businessbreaking trust (in the first sense) in themarketplace.The virtue of trust is critical in a free-marketeconomy, including for the risk taking—that is, entrepreneurship and investment—thatdrives economic growth forward.High degrees of trust must exist inthe economic system, in the government,in businesses, and in consumers.The entrepreneur needs to have trust incapitalism itself. While no outcome isguaranteed and the risks are formidable,the entrepreneur must trust that he willhave a fair opportunity to pitch to investorsand sell to consumers. Entrepreneursand investors need to trust that theirproperty will be protected and that theywill have at least a shot at returns commensuratewith their risk taking. Withoutsuch trust, an economy stagnates.These foundational issues rely on whetherwe can trust government in its actions andits self-restraint. Can we count on the governmentto protect private property; maintainthe currency; limit tax and regulatoryburdens; enforce contracts; prosecutefraud; and leave production, price, andprofit matters to competition and ultimatelyconsumer decisions in the marketplace?Indeed, it is most often when governmentfails to do its basic jobs, or reaches far beyondits core duties, that the economy falters.Weak property protections or thegovernment actually usurping privateproperty, runaway inflation, destructivelevels of taxation or regulation, rampantcrime, price controls, all rank as violationsof trust by the government that underminea market economy. Unfortunately,since government is guided so often not byprinciple but instead by politics, power,and pandering to various interests, politiciansoften do break that trust.Fortunately, the private sector operatesunder a different set of incentives. No matterwhat one’s ultimate motivation is, considerationmust be given to others. Inorder to meet one’s own needs and desires,one must first provide a good or service demandedby others. Failure to meet or createnew demands, to be efficient, and to“Businesses have to beable to trust consumers....If entrepreneursand businessesproduce goods and servicesin honest fashion,they should not expectto be sued.”offer the best quality at the lowest pricemean losses and eventually going out ofbusiness. The free-market system of incentivesand competition fosters trust in businessamong consumers.But we often do not think about the factthat trust must flow in the opposite directionas well. Businesses have to be able totrust consumers. What does this mean?Today, it’s largely about abuse of the legalsystem. If entrepreneurs and businessesproduce goods and services in an honestfashion, they should not expect to be sued.Yet that most certainly is not the reality forAmerican businesses. Trust has been brokenin recent times, as lawyers have unjustlybrought frivolous lawsuits againsthonest businesses, with the courts shamefullyallowing such lawsuits to proceedand the government sometimes even participatingas a litigant, as when variouslocal governments brought lawsuitsagainst gun manufacturers.According to Towers Perrin-Tillinghast,4 Religion&Liberty

Trust and EntrepreneurshipU.S. tort costs hit $260 billion in 2004. Thisequated to 2.22 percent of the GDP, comparedto tort costs equaling 0.62 percent ofthe GDP in 1950. That’s a 348 percent explosionin tort costs as a share of the GDP.And these costs do not include litigationavoidance costs, ranging from unnecessaryand duplicative medical tests ordered bydoctors as a defense against possible malpracticeallegations, to the disappearanceof certain products or whole industriesfrom the marketplace because of highproduct liability costs.In a June 1, 2006, story about small businessesbeing the target of unsavorylawyers, the New York Times noted:Litigation costs for small businessescan prove disastrous, if not fatal, becausethe companies survive on thinprofit margins and lack the infrastructureto handle lawsuits, according tothe Small Business Administration. Anaverage civil case can cost $50,000 to$100,000 to litigate through to a trial,according to an October study conductedby the Klemm Analysis Groupfor the association.Lawsuit abuse most certainly represents abreakdown of trust in the marketplace.When trust is shaken, we ultimately musttake a look at the morals and values thatunderpin society itself. No doubt, the riseof secularism and spread of relativism havehad their effects.A rejection of God also means a rejectionof his commandments, including the commandment“You shall not steal” (Exodus20:15). Martin Luther offered the followingexplanation regarding this commandment:“We are to fear and love God, sothat we neither take our neighbors’ moneyor property … but instead help them toimprove and protect their property and income.”With God and the moral imperativewiped away, however, this view canbe easily replaced by the cynicism of whatone can get away with without beingcaught by the customer, boss, shop owner,cashier, cop, or prosecutor.Meanwhile, the phrase “I’ll sue” hasgrown so commonplace that few seem tothink twice about hauling others intocourt. St. Paul reprimanded members ofthe church at Corinth for bringing lawsuitsagainst each other (1 Corinthians 6:7). Asfor responding to lawsuits, Jesus declared:“If anyone wants to sue you and takeaway your tunic, let him have your cloakalso” (Matthew 5:40). This does not meanthat we must suffer all abuses, but thatlawsuits should be the rare exception andforgiveness the rule.For many, the answers to receding lines offaith are expanding lines of government.But government action is not enough tosecure trust. Eventually the required governmentenforcement in a society of losttrust would lead to a police-regulatorystate, governmental abuse, and the loss offreedom. Even many Christians, however,go down the path of seeing big governmentas the answer to so many problemsthat come with a loss of trust. Yet, thepsalmist wisely warns: “Put not your trustin princes” (Psalm 146:3). Christiansshould understand the sinful aspects ofhuman nature, which are not suspendedin government, but instead often are empoweredthrough acquisition and concentrationof power and by spending otherpeople’s money. When it comes to trustand the government, big is bad.This brings us back to big in the market,namely, trusts. Were they really bad? Anunderstanding of how the economy actuallyworks and market developments inthe nineteenth century tell a different taleabout trusts than what many commonlybelieve today.In his massive 1996 tome Capitalism: ATreatise on Economics, George Reisman explainedthat given the limitations of corporatelaw at the time, trusts were the meansfor accomplishing mergers. What were theactual results? Reisman notes that “thetrusts played a major role in improving theefficiency of the economic system, andthus in raising the general standard of living…The era of the trusts was the era ofAmerica’s most rapid economic progressand the transformation of the country intothe world’s foremost industrial producerand economic power.”So, the trusts of the nineteenth century actuallydid not break trust in the marketplace.Instead, they were rather fantasticexamples of entrepreneurs who servedconsumers well. A sober assessment oftheir impact points to fulfillment of thetrust placed in entrepreneurs.In the end, Jesus instructs: “Trust in God”(John 14:1). From that trust comes a loveand respect for our fellow man that createsthe trust necessary for us to fulfill ourwork, our callings, in this life.Raymond J. Keating is an economist, a columnistfor Newsday on Long Island, and alsowrites for OrthodoxyToday.org.Summer 2006 | Volume 16 | Number 35

Getty ImagesSecond-Career Clergy andParish BusinessAn Interview with Jonathan EnglertIn the 2002–2003 academic year, the journalistJonathan Englert followed five seminariansthrough one year of seminary.Their stories are told in Englert’s newbook, The Collar: A Year of Striving and Faithinside a Catholic Seminary, published in Aprilby Houghton Mifflin. In a phone interview,Jonathan Englert spoke with R&Lmanaging editor, David Phelps about therelationship between business sense andthe needs of parish life._____________________________________The seminary in The Collar is what’s called asecond-career seminary, a seminary for menwho have come to their vocation later in life.Some of the seminarians featured in the work,like the retired marketing executive Jim Pemberton,come from significant careers in the businessworld. What are these men looking for in thepriesthood, and do they make good priests?I think that at the center of that question isa mystery, right? What are they lookingfor? One of the reasons I called this bookThe Collar was because of the sense of thesemen being collared, being brought to aprofession, being brought to this new life,and not always willingly. It’s somethingthat they sometimes struggle with.[But ultimately,] I think they are lookingto serve. Jim Pemberton is a good example.He knows that he has all of this experience—lifeexperience, but specificallybusiness experience. He has four decadesof working in a corporate environment,working on deadlines, working on largelogistical planning, having a successful career.And one component of a successfulcareer was, for him, time management. Heused to tell me that having the corporatecareer gave him the ability to handle thediverse stresses that he knew he was goingto be encountering as a priest. And it alsowas going to equip him with the ability tomanage the parish finances and otherparish issues that come up that mostpriests are going to have to handle.But do they make good priests? I wouldsay yes. Being a good business person isnot necessarily essential to being a goodpriest, but it definitely gives them an edgein certain areas. You have to remember,there is a strong managerial function intoday’s priest. That wasn’t always the case.Most priests now have to oversee largeparish staffs and take up the slack to runvarious programs. And that managerial aspectis obviously well informed by havinghad a corporate career where they were incharge of large staffs and various projects.How do seminarians prepare to address theThe Collarbusiness of a parish?There are practical steps that they take. Atseminary, they don’t take Parish BusinessManagement 101. But they do have frequent,usually weekly, meetings or seminarsin which people come from outside ofthe seminary, people who are involved inministry of some form. Sometimes they’repriests, sometimes they’re nuns who runprograms at parishes, and sometimesthey’re lay people who run finance programsin parishes. So they encounter peoplewho are bringing their life experienceor their work experience in parishes to theseminary so that they can get a sense ofwhat they’re going to face.But I think you’re focusing on somethingthat is very important: the managerial aspectof priesthood is going to become a lotmore important as the numbers decline,because the priest is going to have to managethese large staffs that are going to betaking up a lot of the slack. Jim Pembertondefinitely felt it’s better to be a good man-by Jonathan EnglertHoughton Mifflin320 pp. Hardcover $25.95ISBN 0-618-25146-46 Religion&Liberty

“Being a good businessperson is not necessarilyessential to being a goodpriest, but it definitelygives them an edge incertain areas. You haveto remember, there is astrong managerial functionin today’s priest.”ager than a micro-manager. He came frombusiness. He thought that if a young guycame into the priesthood, for example,who didn’t have this business background,he might feel obliged to do everything, torun every aspect and be totally in controlof every aspect of the parish work, eventhough it would be beyond his expertise.And Jim used to say, “Well, as a managerwith all this experience, I know that thereare things beyond my expertise. I knowthat there are things that people are goingto do better than I can, and those peopleshould be in those positions to do thosethings.” His idea was that if in his parish hehad a parishioner who wanted to get moreactive in the church, a CFO or an accountantfor example, he’s probably going towant to tap him for some fairly importantrole in dealing with the parish’s finances.He saw that [his managerial experience]gave him the ability to screen people, to figureout where they’re going to do the bestwork so that he would be free to get to thehospital, say Mass, and hear confessions.<strong>Acton</strong> FAQHow does <strong>Acton</strong> communicate its ideas to theworld?As a research and educational institution, the <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> has always heldthat its advancement of a “free and virtuous society” must reach the widest possibleaudience to be effective. You don’t change the world by shutting yourselfup in an ivory tower.You may think of <strong>Acton</strong>’s research, publication, and communications efforts asa spectrum that, on the one side, starts with serious, well respected academicwork and, at the other, reaches into the popular media of newspaper commentaries,talk radio, and online media such as Web sites, blogs, and podcasts.Video will be an increasingly important tool for <strong>Acton</strong> in the future.All of <strong>Acton</strong>’s intellectual work is based on the firm foundation built by the institute’sresearch department and its flagship publication, The Journal of Markets& Morality. Other communication vehicles include books, monographs, policypapers, Religion & Liberty, the <strong>Acton</strong> Notes monthly bulletin, and the weekly online<strong>Acton</strong> News & Commentary newsletter. <strong>Acton</strong> understands its various audiences,and reaches them where they are.Why is this important? Because the “war of ideas” on religious, economic, andsocial issues is waged on many fronts. And very often, media such as televisionand film produce the most lasting changes in popular opinion and cultural attitudes.That’s why left-liberal types like Michael Moore and Al Gore are in thedocumentary film business today.Writing in 1949, the economist F. A. Hayek pointed out that socialism was amovement launched by an elite group of intellectuals who worked on newspapersand journals and communicated through speeches to convince the massesof the need for their program. “The character of the process by which the viewsof the intellectuals influence the politics of tomorrow is therefore of much morethan academic interest,” Hayek said.Today, the ideas that advance freedom—or hinderit—are advanced globally and instantaneouslywith the latest informationtechnologies. <strong>Acton</strong> is working toensure that its message, needednow more than ever, will beheard in that raucous marketplaceof ideas.Kris Alan MaurenExecutive DirectorAuthor Jonathan EnglertSummer 2006 | Volume 16 | Number 37

The Dividends of SocialCapitalby Michael MillerWhy have so many countries been unableto fully adopt a market economy? The answeris complex, but there are certain basicconditions that must be met for an economyto become free and prosperous. Twothat are non-negotiable are private propertyand the rule of law. Without these amarket cannot exist. An educated workforce,low taxes, and minimal regulationare also helpful.But there is another element that is crucialbut often overlooked—it is what has beencalled “social capital,” specifically the existenceof trust. Francis Fukuyama makesthis case in his 1995 book Trust: The SocialVirtues and the Creation of Prosperity.Why are trust and social capital so importantfor economic success? In a moderneconomy based on ideas, organization, andtechnology, a key element is human interaction—andhere trust is essential. If a cultureplaces importance on virtues that helpcreate prosperity—honesty, fairness, personalresponsibility, the importance of hardwork, and respect for law—it creates an atmosphereof trust, which engenders spontaneousand voluntary collaboration andcreates the conditions where business andentrepreneurship can flourish. If thesevirtues are not esteemed, or if trust existsonly within familial or tribe relationships,it is difficult to organize and create businesses,and there is a greater need for thestate to organize and maintain order.Fukuyama gives the U.S., Germany, andJapan as examples of high trust societies,which explains their large private sectorsand much of their economic prosperity.France, Italy, and Latin America on theother hand are “familistic” societies wheretrust outside of kinship is quite low. Acountry without a high degree of socialcapital finds it more difficult to collaborateand organize complex enterprises. Wheretrust is lacking, the cost of doing businessincreases and opportunities are lost.Fukuyama argues that while the neoclassicalmodel of economics is generallycorrect, it ignores the importance ofculture—and I would add religion and aproper vision of the person. But whilemodern economists often miss this area,the classical economists from the lateSpanish scholastics in the fifteenth and sixteenthcenturies to Adam Smith understoodthat a market was composed ofhuman persons acting together. Thescholastic theologians and philosophers developedmodern market price theory in thecontext of ethics and moral theology, andwhile not explicit, Smith presupposed aChristian society of shared values as thefoundation of the market economy. His famousbutcher, baker, and brewer example,meant to illustrate division of labor and thepositive power of self interest, only works,of course, if the butcher knows that thebaker is not a scoundrel. If the baker is notto be trusted, the cost of doing business increases.The butcher has to hire a lawyer tomake sure that a contract is right, spendextra time and money reviewing the order,and possibly appeal to the legal authoritiesfor recourse.All of these are what economists call transactioncosts. The higher the transactioncosts, the higher the cost of doing business.But there are other losses that are hard tomeasure but no less real. Low trust andhigher transaction costs mean more lostopportunities altogether. Widespread entrepreneurshipcannot flourish in a societywhere trust is lacking because the risk isincreased.Trust: The Social Virtues andThe Creation of Prosperityby Francis FukuyamaFree Press480 pp. Paperback $16.00ISBN 0-684-82525-28 Religion&Liberty

Ten years ago Fukuyama warned that anincreasingly individualist and litigiousAmerica would weaken its long-term economicpossibilities. A sustainable free marketcannot rest on an ethical frameworkthat makes truth relative and exalts individualism.A society composed of “economicman” who cares for nothing buthimself and his own consumption cannotlong support a free economy. Strong familiesand a network of voluntary social relationshipssuch as churches and service organizationsare needed to maintain thesocial and organizational fabric of the freesociety.Many view America as an individualistcountry, but as Fukuyama (and Tocquevillebefore him) correctly points out, this is historicallyincorrect. While they are anti-statist,they are in fact more communal andcollaborative than the French, Italians, orCanadians, engaging in more voluntary associationsand private charities. America isa land of entrepreneurship and private enterprisenot because it is composed ofatomistic individuals but because of Americans’propensity to trust one another tosolve their problems and not to rely on thestate to do it for them. An individualist andrelativist America would not long be aprosperous one.Social capital is also important for businessethics. A culture that values the socialvirtues results in decreased infringementsbecause there are entire networks of relationshipsand shared values that frown onsuch behavior, creating an atmosphere ofpositive peer influence, which is more effectivethan the law—an outside authority.Fukuyama has a powerful argument thatrequires our attention. Those cultures withhigh levels of trust have an economic advantage.In other words, economies benefitif the market can rely on the virtue of itsparticipants.Michael Miller is the director of programs at the<strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong>.Double-Edged Sword:The Power of the WordDeuteronomy 25:13–16“You shall not have in your bag two kinds of weights, a large and a small. You shall not havein your house two kinds of measures, a large and a small. A full and just weight you shall have,a full and just measure you shall have; that your days may be prolonged in the land which theLORD your God gives you. For all who do such things, all who act dishonestly, are an abominationto the LORD your God.” Deuteronomy 25:13–16This instruction is found in a large section of legislation given to the people of Israel aspart of the covenant God initiated with them. In Deuteronomy, a code of behavior isset forth that articulates the nation’s distinctrelationship with God.It is among such[detestable] companythat the law placesone who cheats anotherout of a fewcents in business.essYet interspersed between these laws dealingwith major issues, we find several regulationsregarding what would be consideredrather commonplace occurrences. This particularinstruction deals with the basic flowof commerce. In the world of Deuteronomy,most every transaction in the marketplaceinvolved using balancing scales with standardized weights to measure out quantities ofgoods for buying or selling. It could be very easy to increase profit margins surreptitiouslyby altering the weight of one’s stones, using a heavier stone to get more for one’smoney when buying and a lighter stone to give customers less for theirs. Obviously thisis not ethical, but one might question how much might be gained by such a practice asthe fraudulent stones had to be close enough to the standard weight to convince theother party that the transaction was legitimate. The gains per transaction probablyamounted to a very incidental amount, making this the kind of offense that would giverise to some head-shaking with the acknowledgement that, while wrong, it is not thatbig a deal, as many might have done it.But it is important for us not to rationalize such infractions, because Scripture assignsthem gravity. Verse 16 does not say: “It’s not that big a deal”; instead it says: “all whodo such things, all who act dishonestly, are an abomination to the Lord your God.” Thisis strong language—an abomination? There are other practices in Deuteronomy that aredescribed as abominable, practices with a more readily identifiable detestable naturesuch as sorcery, idolatry, and offering children in pagan rites. It is among such companythat the law places one who cheats another out of a few cents in business. Such anaction is an abomination to God, it is repugnant to him and an insult to his characterif one names his name, yet engages in this practice. —A submission by Rolf Geyling.Summer 2006 | Volume 16 | Number 39

Defending the Weak and theIdol of Equalityby Jennifer Roback MorseJennifer Roback MorseThe <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> has begun a series of lectures—eightin Rome and one in Poland—celebratingthe fifteenth anniversary of CentesimusAnnus, Pope John Paul II’s landmarksocial encyclical. The lecture series started in Octoberof 2005 and will continue through 2007.For the next year, Religion & Liberty will featureexcerpts from these conference lectures.The following is taken from Catholic SocialTeaching on the Economy and the Family:an alternative to the modern welfare state,delivered on January 21, 2006, at the PontificalNorth American College in Rome.People unfamiliar with Catholic socialteaching may be surprised to learn that thechurch has consistently condemned socialism.The Catholic Church has never embraced“equality” the way socialism has.The church is not indifferent to the poor.Rather, the church proposes an alternativeprinciple for helping them. Instead of“make everyone equal” as a guiding premise,the church proposes “defend theweak” as the appropriate posture towardthe poor. These approaches have differentfactual foundations and distinct policy implications,especially with regard to society’smost basic institution, the family.Beginning with Leo XIII and continuinguntil John Paul II, the church has consistentlycondemned socialism. Leo XIII realizedthat the godlessness of socialism is notan incidental flaw in an otherwise nobleideal. Godlessness is at the core of the ideologybecause socialism created idols outof the state and the idea of equality. Thiscreates deep and subtle problems. Whilethe state is a necessary institution, it is alimited institution, incapable of solvingevery human problem. By replacing Godwith the state, socialists will almost certainlyover-empower the state and takeeven its legitimate functions to illegitimateextremes.In Leo XIII’s words from Rerum Novarum,“Let it be laid down in the first place that acondition of human existence must beborne with, namely that in civil society thelowest cannot be made equal with thehighest.” Leo understood that creatingeconomic equality was a fool’s errand.While it is true that some forms of inequalityare unjustified, a certain amountof inequality is inevitable and even justified.By making equality the summumbonum of society, socialists take the nobleideal of compassion for the poor and twistit into a form of idolatry.The church’s alternative to the idolatry ofequality is the defense of the weak. AsJohn Paul said in Centesimus Annus, “LeoXIII is repeating an elementary principle ofsound political organization, namely, themore that individuals are defenseless withina given society, the more they requirethe care and concern of others, and in particularthe intervention of government authority.”Focusing on the weak is realistic in a waythat focusing on inequality is not. All of usbegin our lives as helpless infants, completelydependent on the care of others forour survival. If we are lucky, we live longenough that we again need the assistanceof others just to manage our basic bodilyneeds. In between, all of us get sick someof the time and temporarily need help.Any of us could get a bump on the headthat would render us permanently dependanton others.The progression from infancy to adulthoodis not some freak occurrence that could besomehow eliminated by proper social engineering.This is the story of every humanlife. Aging, accidents, and illness can neverbe eliminated either. Yet our modern“The church’s alternativeto the idolatry of equalityis the defense of theweak.”world, it is safe to say, is profoundly uncomfortablewith weakness and dependence.We fear it in ourselves. We tend todistance ourselves from it in others.Jesus told us, “The poor you will alwayshave with you.” It is not possible to eliminatecompletely all differences in the materialconditions of every person in society,as the socialists propose. At the same time,the continued existence of the weak demandsa continual response from theChristian.It is now abundantly clear that “defend theweak” is a very different ethical mandate10 Religion&Liberty

Defending the Weak and the Idol of Equalityfrom “create equality.” For equality is not astand-alone objective that always andeverywhere legitimately takes priority.Equality requires a referent. The politicalsystem must make some judgments aboutwho must be equal to whom, for whatpurposes, and in what contexts.As the socialist impulse has unfoldedthroughout the industrialized world, manypeople have been necessarily excludedfrom its concern with equality. The youngcannot be made economically equal to theold, so the young are excluded from thelabor market. The non-voting immigrantsneed not be made equal to the native-borncitizens.Even more chillingly, the physically weakand incapacitated can never be made equalto the strong. Throughout the world,where equality has been made into an idol,powerful political forces operate to completelyexclude these people from the mostbasic protections of law. In the Netherlands,“voluntary” euthanasia—which isnot always voluntary—relieves society ofthe ill and the old. And of course, the infantin the womb has been excluded inmany secularized countries from any legalprotections whatsoever.One of the most destructive applications ofpolitical equality is the drive to make menand women equal. This essentially politicalimpulse has poisoned relationships betweenmen and women inside the familyand in the public square. Modern womenbelieve they do not need husbands for financialsupport or any other kind of help.Young parents seem surprised to find thatmothers and fathers are not truly interchangeable.Society is on the verge ofclaiming that gender is an irrelevant categoryfor marriage, for child-rearing, oreven for sex itself. In other words, thereare voices in our modern culture trying toconvince us that we ought to be indifferentas to whether we prefer a same-sex partnerto an opposite-sex partner. This is trulyequality gone out of control.“Throughout the worldwhere equality has beenmade into an idol, powerfulpolitical forces operateto completely excludethese people from themost basic protections ofThe Catholic vision of the family sees menand women as complementary to eachother, not as competitors with each other.Marriage is inherently a gender-based institution,because it helps men and womenbridge the natural differences betweenthem. Marriage is the school and householdof love. Within the household, menand women learn to help each other, to cooperatewith each other, and to understandeach other. This is a very different visionthan the image of husbands and wivesat each other’s throats, in competition fordominance and power inside their ownhomes.Catholic social teaching insists on supportingthe family, economically and politically.Catholic social teaching defends thefamily as a pre-political reality independentof the state and with claims against thestate. In Centesimus Annus, John Paul reiteratesthis point, originally made by PopeLeo XIII in Rerum Novarum. “He (Leo XIII) frequently insists on necessarylimits to the state’s interventionand on its instrumental character, inasmuchas the family and society areprior to the state, and inasmuch as thestate exists in order to protect theirrights and not stifle them.The ethical principle of defending the weakplaces distinct demands upon us as individualsand as a society. The Catholic visionrespects the family as the great pre-politicalsocial institution, and marriage as the mostbasic unit of social cooperation. The familycan accommodate the inherent inequalitiesacross the generations and across thesexes. Inside the family, the strong are naturallyinclined to take care of the weak.By contrast, the state plants itself firmlyagainst the organic reality of the family.The state demands the right to redefine thefamily in the name of equality. Equality forwomen means unlimited legal entitlementto abortion. Marriage equality has come tomean any combination of adults, participatingin any form of sexual activity, forany length of time, with or without thepossibility of begetting children.Equality for adults means misery for theweak. It is time to abandon the quest forequality. Defending the weak should beour guiding Christian principle.Jennifer Roback Morse, Ph.D. is a senior fellowin economics at the <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong>. She can becontacted through her Web site, www.jennifer-roback-morse.com.Summer 2006 | Volume 16 | Number 311

Arrow interview continued from page 3Well, I think you’re asking two quite differentquestions. One is the use of economicexplanations for things that youthink of as part of other social sciencefields. It’s true that economists do havesomething to say about other fields. Herethe problem is that you get one-sidedviews—namely the economic perspectivealone. You are not getting irrelevant statements;they are not meaningless statements,but just one-sided or incomplete.For example, some of the claims of economicsabout motivation, if correct, areapplicable in other fields, and that was alreadypointed out when the utility theorieswere being developed in the 1880’sand 1890’s.natic about playing chess in a way that getsin the way of doing good deeds.Beyond a certain point, material goods canbe symbols of success, but they can’t reallyimprove your life very much. Yet somehowthese things have a way of becomingnecessities. This is a real phenomenon. Anumber of psychologists and economistsinfluenced by them have been arguingthat happiness, whatever it may mean, isall relative to a previous standard of living.Relatively speaking, if you ask people,what they need to be thoroughly happy orhow much income they need to really bethoroughly satisfied in an economic sense,they will typically answer 20 percent morethan they’ve got now.So while it’s hard to define these terms andsome economists don’t like to make comparisonsto which they can’t give definitemeaning, the typical thing you find is thatrich people are happy and poor people notall that much less happy. If you comparecountries, the average happiness in poorcountries is the same as that in rich countries.(I’m not talking about extremelypoor countries.)One of the most striking things to me issome surveys [that measure happiness]that were done in Japan every few years,and, if I remember the dates, the answersin 1958 to 1988 were roughly the same. Ifyou draw the curves relating happiness toincome, you could not tell them apart.Now that was one of the most rapid periodsof economic growth any country hasever experienced. They were pursuing materialgoods very, very vigorously. The pursuitof material goods may have very littleto do with satisfaction.On the other hand, divorce shows up as abig negative factor in measuring happiness.Material possessions play a role inhappiness, I think, but it’s just a role.The danger of excessive reliance on themarket, excessive perception of the market,is that it will obscure these other,clearly more fundamental courses of happinessor unhappiness. If you spend allyour time at this instead of building upyour relationships, there can be a real priceto pay.A temptation of any academic discipline—especiallyin the social sciences, but also in the naturalsciences—is to explain more than the disciplineis competent to do. Are there areas of economicstoday that you think are overstepping itslimits? And then, to what degree does the worldof metaphysics, philosophy, and theology pointout that there are areas beyond the market, beyondeconomic analysis?We see, by the way, that today psychologyis invading economics—the whole field ofbehavioral economics. I believe that sociologyshould play more of a role in economicsthan it does. The way people behave ineconomics is partly influenced by howother people behave. It’s easy to point outexamples, but it’s not so easy to constructa broad theory.You raise a different question when youask if things like metaphysics, theology,and moral philosophy play a role. Nowyou’re coming to the question of the realmof value versus the realm of description.It’s clear there are value questions of howone “ought to act” that are not going to beanswered by a description of how peopledo it. Economics is not going to answerthat question because it can’t answer it. It’sjust a logically different thing.We draw on religious sources about howone should act. We used to have, in theMiddle Ages, very elaborate regulations ofcommerce—what was permissible commercialbehavior and what is not permissiblecommercial behavior—derived from“Material possessions playa role in happiness, Ithink, but it’s just arole.... The danger ofexcessive reliance onthe market ... is that itwill obscure these other,more fundamentalcourses of happiness orunhappiness.“12 Religion&Liberty

“Religion calls for a senseof responsibility to theother, which the market,in principle, doesn’thave.... Those valueshave to come from elsewhere,and this is whatis emphasized by Christianand Jewish thoughtabout the economy.”the laws on usury, the apparent prohibitionon interest, [etc.] And the same thingis happening in Islamic law now, accordingto things I’ve read. There is the so-calledIslamic banking, which claims not tocharge interest—but does, as had happenedin the Christian world also.Does social analysis today neglect the question ofthe intermediate, private charity collective actionthrough churches, through families—thesekinds of transactions that are not strictly speakingprivate and not for state?I don’t want to say this is a void field, but Ithink the tendency when anyone thinks ofa policy is that either individuals should doit for themselves or the state should do it.I’m struck by the fact that there are a numberof situations where the policy expertdoesn’t understand that there are other institutions.There are many cases wherethese other institutions are probably superior,because the state has constraints on itsactions, even the ideal state, leaving asidecorruption and things like that. The statehas to treat people in some uniform way.You don’t want the state to start makingtoo many distinctions or the potential forcorruption or unfairness arises. So youhave rules. Well, these rules tend to bebroad and not very applicable to particulars.They don’t take account of the individualcase. In a way, you don’t want themto, but that means that their effectivenessis reduced and something more flexiblecan be achieved by using intermediate institutions.For instance, we have such institutions fordistributing resources—what we call charitablegroups. But such institutions alsoexist for agitation to bring matters to thepublic concern, changing people’s values. Ithink the church is playing this major rolein dissemination of these values and judgmentsand forming a focal point for them.Your Jewish faith has a rich tradition of moralconsideration, both moral philosophy andmoral theology, and a very sophisticated Biblicalvision of what the economic life of the ChosenPeople would look like. For someone who is atthe very peak of his field in economics, what lessonshave you picked up from nearly twentyyears of frequent contact with Christians, andparticularly Catholics, thinking about thesethings?Well, I’ve been really concerned aboutethical questions for a long time. I generallytry to write things I feel sure about. As Iget older, I’m a little more speculative andstart to stimulate other people to thinkmore about it. I think one of the criticalthings is the idea of what’s called tzedakah,loosely translated as charity. It’s the idea ofresponsibility for the welfare of others. Ofcourse, then the problem comes, how doyou institutionalize that? How do you getpeople to take these general beliefs andtranslate them into their own actions?And that’s why collective actions of all levelsplay a role.Like most economists, I find the market avery powerful instrument for achieving efficiency.We’re not wasting things. We’renot wasting resources. So whatever getsthere, gets there. Nevertheless, there are alot of limitations. For instance, there areintrinsic limitations like the kinds Isketched out earlier because of the existenceof private information.Religion calls for a sense of responsibilityto the other, which the market, in principle,doesn’t have. In fact, the markets dohave it because they need fairness and efficiencyto some extent. Yet the logic ofmarkets means that such considerationshave to be modeled as totally self-regarding,and people are not totally self-regarding.It’s helpful to model them in that way,I’m not going to deny that; but it’s not theset of values by which you want to live.Those values have to come from elsewhere,and this is what is emphasized byChristian and Jewish thought about theeconomy.Spring 2006 | Volume 16 | Number 313

In the Liberal TraditionAnders Chydenius [1729–1803]“The more opportunities there are in a Society for somepersons to live upon the toil of others, and the less thoseothers may enjoy the fruits of their work themselves, themore is diligence killed, the former become insolent, thelatter despairing, and both negligent.”Known as the Adam Smith of the North, Anders Chydeniuslaid out his economic prescription for mercantilist [Sweden-Finland] in The National Gain in 1765, suggesting a concept ofspontaneous order eleven years before Adam Smith in TheWealth of Nations: “Every individual spontaneously tries to findthe place and the trade in which he can best increase Nationalgain, if laws do not prevent him from doing so.”For Chydenius, freedom and diligence were the foundations ofan economically prosperous nation; direction from the governmentonly gummed up the gears of a natural system of humaninteraction.Thus the wealth of a Nationconsists in the multitude ofproducts or, rather, in theirvalue; but the multitude ofproducts depends on twochief causes, namely, thenumber of workmen andtheir diligence. Naturewill produce both,when she is left untrammeled… If eitheris lacking, the faultshould be sought inthe laws of the Nation, hardly, however,in any want of laws, but in the impediments that are put in theway of Nature.“Every individual spontaneously tries tofind the place and the trade in which hecan best increase National gain, if lawsdo not prevent him from doing so.”Pastor, politician, writer, doctor, scholar, scientist, experimenterin plant and animal husbandry, economist, musician, proponentof freedom and enterprise—Chydenius was a renaissanceman in the Age of Enlightenment, careful to root his ideas onhuman dignity in divine providence. Chydenius asked:Would the Great Master, who adorns the valley with flowersand covers the cliff itself with grass and mosses, exhibit such agreat mistake in man, his masterpiece, that man should not beable to enrich the globe with as many inhabitants as it can support?That would be a mean thought even in a Pagan, but blasphemyin a Christian, when reading the Almighty’s precept:‘Be fruitful, multiply and fill the earth.’The National Gain, written originally for the Stockholm Diet in1765–66, caused Chydenius’s own party to exclude him fromfuture representation. Chydenius retreated into his parishwork until 1778 where once again he challenged the Diet withhis advocacy for workers’ rights, later set down in a letter to theRoyal Economic Society:The Creator only put people to work, but did not stipulate thetype of work each of them should do. Stealing was the onlything that the Almighty prohibited, but no target was set fordiligence, how far it was allowed to go or what sort of thingssuch diligence produced. He did not tie anyone to the ploughnor did He tie anyone to trade guilds but merely when andwhere each one perceived how best to make a living where hecould better himself.14 Religion&Liberty

Rev. Robert A. SiricoFairness in the MarketHow, in a market setting, can you beassured that you are getting a gooddeal? We all know people who distrustevery price, believe that mostbusiness people are concealing somethingimportant, and have a vague suspicion that every enterpriseis a racket.These people might have a bias, but they do serve a marketfunction. Business must always be aware that its promotionalsand marketing plans must be balanced against the need to inspiretrust always. It is a business asset like no other, and thosewho foster it thrive, while those who do not lose out.But we need to be aware that the price of goods on the marketis not fixed by some eternal law but rather by fluctuationsbased on supply and demand. There is nothing in the structureof the universe that makes paper towels pennies a piece, dishtowels a dollar, and linen tea cloths as high as fifty dollars.These prices are a result of the item’s relative scarcity and its relationshipto the intensity of consumer interest.What is a good deal? It is the point at which buyer and selleragree and exchange property titles. That is all. That is why themedieval theorists who looked into this matter concluded thatthe “just price” and the “just wage” are identical to the marketwage provided there has been no force or fraud and good faithis being shown by all parties.Consider what the old classical economists termed the “diamond-waterparadox.” Why does water, which is necessary forlife, sell for so much less than a diamond, which is not necessary?It has to do with their relative abundance, for the situationwould be completely reversed in a desert where water ishard to come by.To be sure, we make a grave error if we conflate the value ofsomething with its price. Some goods and services of infinitevalue sell for a very low price (I’m thinking here of some booksof prayers I’ve found in thrift stores for pennies!) while somehigh-price items have very low value when considered in amoral sense. But the job of the market is not to provide an objectivemeasure of moral worth, but merely to produce and allocatedemanding goods and services with an eye to efficiency.The price provides us a signal to conserve resources. We wasteresources that are low in price, while we conserve resourcesthat are high in price. We don’t often think about the extent towhich our lives are managed with such signals in mind. But ifyou travel to less developed countries, you find that whatAmericans routinely toss out sells for a very high price in poorcountries.Does this make Americans wasteful or even immoral, as manycommentators claim? Not as a general rule. What is conservationand what is waste can only be measured by the price systemin a market setting. As economies develop, the prices ofnecessities fall, provided the system is working as it should.“The market economy is driven by dynamicchange and innovation...it becomesall the more important, then, thatour sense of what is right and true befixed with an eye to eternal concerns.”Actually the Bible is filled with stories that involve fluctuatingprices. I’m thinking of the parables of the laborers in the vineyard,the pearl of great price, and the treasure in the field. Allinvolve surprising turns of events reflected in price changes.The market economy is driven by dynamic change and innovation,and this can sometimes be destabilizing to our way oflife. It becomes all the more important, then, that our sense ofwhat is right and true be fixed with an eye to eternal concerns.It is morality that is our Rock of Gibraltar in a changing world.Rev. Robert A. Sirico is president of the <strong>Acton</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> for the Studyof Religion and Liberty in Grand Rapids, Michigan.Summer 2006 | Volume 16 | Number 315

ReviewsThere’s No Such Thing as “Business” EthicsBy John C. Maxwell • Warner Faith, New York, NY, 2003160 pp. • $14.95Review by Sarah SalbThe wave of recent corporate scandalshas spurred an increased interestin business ethics. As illegal andunethical behavior is exposed inthe business world, society has demanded reform.In his book, There’s No Such Thing as “Business” Ethics, John C.Maxwell firmly contends that there is no difference between businessethics and general moral behavior. “There’s no such thing asbusiness ethics,” writes Maxwell, “there’s only ethics. People tryto use one set of ethics for their professional life, another for theirspiritual life, and still another at home with their family… If youdesire to be ethical, you live it by one standard across the board.”He believes that people behave unethically because of the convenienceand the desire to win no matter the cost. In addition,people rationalize their choices with relativism by choosing theirown ethical standards to guide their behavior.To guide the ethical mindset and establish an “integrity guideline,”Maxwell stresses the Golden Rule, a principle rooted inmany diverse cultures, ranging from Judaism to Zoroastrianism:one should not do onto others what they would not want doneto themselves. Maxwell believes that people need to have firmethical principles guiding their personal lives and shaping theircharacters, and must translate this behavior into all other aspectsof their lives as well.Part of the beauty of the Golden Rule is its simplicity and universality.It applies to anyone, in any given circumstance. Maxwellexplains how the rule is intuitively correct, since no one wishesto be treated worse than he treats others. By valuing others andtreating others the way you want to be treated, everyone wins.The Golden Rule not only gives direction and guides business endeavors,but also builds character and helps one lead a more productivelife. It is essential that ethical standards be absolute inorder to foster a sense of integrity and responsibility.Using numerous examples, Maxwell tries to convince the readerthat adhering to the Golden Rule is a necessary component ofsuccess. He substantiates his point by showing how the longlastingprofitable companies do follow strong ethical standards.Synovus, for example, is ranked in the top ten of the 100 BestCompanies to Work For in America and has had one of the higheststock returns on the New York Stock Exchange in the past twodecades. In contrast, those that compromise on ethical standardsoften lose out on the long run, as exemplified by the Enron case.The company demanded that profits be shown every year bybooking future revenue immediately, and thus needed to keepbooking more deals each year to maintain gains.The concentration on ethics in an organization needs to be genuineand not watered down. When companies implement businessethics courses solely for external purposes, to avoid or mitigatelegal persecution, they are ineffective in establishing true integrityin the workplace. Maxwell also claims that five factors underminethe Golden Rule and can cause ethical violations: pressure,pleasure, power, pride, and priorities. He then suggests arule that goes above and beyond the call of duty of the GoldenRule—the Platinum Rule. This principle obliges one to go theextra mile in dealing with others. Maxwell exemplifies the PlatinumRule with an occurrence during the 1964 Winter OlympicGames. Italy’s driver for the two-man bobsled competition, EugenioMonti, donated a bolt from his sled to Tony Nash of the competingBritish team, though it cost his team a medal.Maxwell reiterates his underlying message at the end of the book.He writes, “Those who go for the Golden Rule not only have achance to achieve monetary wealth, but also to receive other benefitsthat money can’t buy.” Although slightly repetitive and simplistic,the book is direct and straightforward with a clear message.Since Maxwell includes a number of thought-provokingquestions after each chapter providing the reader with a chanceto reflect on the chapter’s content and apply its principles, There’sNo Such Thing as “Business” Ethics might prove useful as a springboardfor discussions of business ethics.Sarah Salb is a recent graduate of the CUNY honors college at BrooklynCollege.16 Religion&Liberty