The Family: America's Smallest School (PDF) - ETS

The Family: America's Smallest School (PDF) - ETS

The Family: America's Smallest School (PDF) - ETS

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Policy Information Report<strong>The</strong> <strong>Family</strong>: America’s <strong>Smallest</strong> <strong>School</strong>

This report was written by:Paul E. BartonRichard J. ColeyEducational Testing Service<strong>The</strong> views expressed in this reportare those of the authors and do notnecessarily reflect the views of theofficers and trustees of EducationalTesting Service.Additional copies of this report canbe ordered for $15 (prepaid) from:Policy Information CenterMail Stop 19-REducational Testing ServiceRosedale RoadPrinceton, NJ 08541-0001(609) 734-5212pic@ets.orgCopies can be downloaded from:www.ets.org/research/picCopyright © 2007 byEducational Testing Service.All rights reserved. EducationalTesting Service, <strong>ETS</strong>, and the <strong>ETS</strong>logo are registered trademarks ofEducational Testing Service(<strong>ETS</strong>). LISTENING. LEARNING.LEADING. is a trademark of <strong>ETS</strong>.September 2007Policy Evaluation andResearch CenterPolicy Information CenterEducational Testing ServiceTable of ContentsPreface ............................................................................................................2Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................2Highlights .......................................................................................................3Introduction ...................................................................................................6<strong>The</strong> Parent-Pupil Ratio ..................................................................................8What Research Reveals .......................................................................8Out-of-Wedlock Births .......................................................................10Number of Parents in the Home .......................................................11<strong>The</strong> New Inequality ............................................................................13<strong>Family</strong> Finances ...........................................................................................14Median <strong>Family</strong> Income ......................................................................15Children Living in Poverty ................................................................16Food Insecurity ..................................................................................17Parent Employment ...........................................................................17Literacy Development in Young Children ..................................................19Early Language Acquisition ..............................................................19Reading to Young Children ...............................................................20<strong>The</strong> Child Care Dimension ..........................................................................23A Look at Day Care for the Nation’s 2-Year-Olds .............................23Type of Day Care ........................................................................24Quality of Day Care ...................................................................25<strong>The</strong> Home as an Educational Resource .....................................................26Literacy Materials in the Home ........................................................26Technology .........................................................................................27A Place to Study .................................................................................28Dealing With Distractions .................................................................28<strong>The</strong> Parent–<strong>School</strong> Relationship ................................................................32Getting Children to <strong>School</strong> ................................................................32Parent Involvement in <strong>School</strong> ...........................................................34Putting It Together: Estimating the Impact of<strong>Family</strong> and Home Factors on Student Achievement .................................37Concluding Comments ................................................................................39Appendix Table ............................................................................................42

PrefaceAll parents have witnessed their children doing things,good and bad, which remind them of themselves.<strong>The</strong>se incidents serve as powerful reminders of thecritical role parents play as teachers. Indeed, “theapple does not fall far from the tree,” as the foundationestablished and nurtured at home goes a long wayin ensuring student achievement in school as well assuccess in later life. <strong>The</strong> important educational roleof parents, however, is often overlooked in our local,state and national discussions about raising studentachievement and closing achievement gaps.One of the four cornerstones of <strong>The</strong> OpportunityCompact, the National Urban League’s Blueprint forEconomic Equality, is the Opportunity for Childrento Thrive. Through this guiding principle, we assertthat every child in America deserves to live a life freeof poverty that includes a safe home environment,adequate nutrition and affordable quality health care.We further assert that all children in America deservea quality education that will prepare them to competein an increasingly global marketplace.For the Opportunity to Thrive to be realized, andfor us as a nation to reach the ambitious educationalgoals that we have set for ourselves, we must keepclear in our minds that our family is our first andsmallest school.<strong>The</strong> authors of this report, Paul Barton and RichardColey, tell us how we benefit from paying attentionto the role of our families. <strong>The</strong>y examine many facetsof children’s home environment and experiences thatfoster cognitive development and school achievement,from birth throughout the period of formal schooling.<strong>The</strong>y stress that we should think of strengtheningthe roles of both schools and families, that schoolsneed parents and communities as allies, and thatrecognizing the importance of the role families playshould in no way lessen the need to improve schools.<strong>The</strong> report also reveals the complexity of anyeffort to strengthen the role that families play ineducating children, the many levels on which suchefforts need to take place, and the sensitivity that isnecessary whenever we contemplate the formationand functioning of families — our most importantinstitution, and at the same time our most private one.<strong>The</strong> National Urban League commends EducationalTesting Service for this timely and critically importantreport and joins it in urging parents, educators,administrators and policymakers to consider its findings.Marc H. MorialPresident and CEONational Urban LeagueAcknowledgmentsThis report was reviewed by Carol Dwyer, DistinguishedPresidential Appointee at <strong>ETS</strong>; Drew Gitomer,Distinguished Presidential Appointee at <strong>ETS</strong>; LauraLippman, Senior Program Area Director and SeniorResearch Associate at Child Trends; Isabel V. Sawhill,Senior Fellow and Cabot <strong>Family</strong> Chair at the BrookingsInstitution; and Andrew J. Rotherham, Co-Founder andCo-Director, Education Sector. <strong>The</strong> report was editedby Amanda McBride. Christina Guzikowski provideddesktop publishing. Marita Gray, with the help of her5-year-old son, Ryan, designed the cover. Errors of factor interpretation are those of the authors.

Highlights<strong>The</strong> family and the home are both critical educationinstitutions where children begin learning long beforethey start school, and where they spend much of theirtime after they start school. So it stands to reason thatimproving a child’s home environment to make it moreconducive to learning is critical if we are to improvethe educational achievement of the nation’s studentsand close the achievement gaps. To do this, we needto develop cooperative partnerships in which familiesare allies in the efforts of teachers and schools. <strong>The</strong>kinds of family and home conditions that researchhas found to make a difference in children’s cognitivedevelopment and school achievement include thosehighlighted below. 1<strong>The</strong> Parent-Pupil Ratio. <strong>The</strong> percentage of twoparentfamilies has been in long-term decline. Singleparentfamilies are rapidly becoming a significantsegment of the country’s family population.• Forty-four percent of births to women under age30 are out-of-wedlock. <strong>The</strong> percentage is muchhigher for Black women and much lower for Asian-American women. While the percentage decreasesas women’s educational attainment rises, the ratefor Black and Hispanic college-educated womenremains high.• Sixty-eight percent of U.S. children live with twoparents, a decline from 77 percent in 1980. Only35 percent of Black children live with two parents.In selected international comparisons, the UnitedStates ranks the highest in the percentage of singleparenthouseholds, and Japan ranks the lowest.<strong>Family</strong> Finances. Income is an important factor ina family’s ability to fund the tangible and intangibleelements that contribute to making the home aneducationally supportive environment. At all incomelevels, however, parents have important roles to playin facilitating their children’s learning, many of whichare not dependent upon the availability of money.• Among racial/ethnic groups, Asian-Americanfamilies, on average, have the highest median familyincome; Black families have the lowest.• On average, White and Asian-American familieswith children have higher incomes than White andAsian-American families without children. <strong>The</strong>opposite is true for Black and Hispanic families,however; and these families have much loweraverage family incomes than their White andAsian-American counterparts. <strong>The</strong>re are also largedifferences in family income across the states,ranging from median family incomes in excessof $70,000 in several northeastern states to lessthan $40,000 in New Mexico, Mississippi, andWashington, D.C.• Nationally, 19 percent of children live in poverty.<strong>The</strong> percentages increase to nearly a third or moreof Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, andHispanic children. Among the states, the percentageranges from a low of 9 percent in New Hampshireto a high of 31 percent in Mississippi.• Nationally, 11 percent of all households are “foodinsecure.” <strong>The</strong> rate for female-headed households istriple the rate for married-couple families, and therate for Black households is triple the rate for Whitehouseholds. One-third or more of poor householdsare food insecure.• Rates of parent unemployment are high, and arealarmingly so for some groups. Nationally, onethirdof children live in families in which no parenthas full-time, year-round employment. This is thecase for half of Black and American Indian/AlaskanNative children. More than 40 percent of children inAlaska, New Mexico, Louisiana, and Mississippi livein such families.Literacy Development. Literacy development beginslong before children enter formal education, and iscritical to their success in school.• <strong>The</strong>re are substantial differences in children’smeasured abilities as they start kindergarten. Forexample, average mathematics scores for Black andHispanic children are 21 percent and 19 percentlower, respectively, than the mathematics scores ofWhite children.• By age 4, the average child in a professional familyhears about 20 million more words than the averagechild in a working-class family, and about 35 millionmore words than children in welfare families.1Readers will find sources for the data and definitions of the variables discussed in this section in the main body of the report.

• Sixty-two percent of high socioeconomic status(SES) kindergartners are read to every day by theirparents, compared to 36 percent of kindergartnersin the lowest SES group. White and Asian-Americanchildren, those who live with two parents, andchildren with mothers with higher education levelswere also more likely to have a parent read to themdaily than their counterparts who were Black orHispanic, lived with one parent, or had motherswith lower educational levels.Child Care Disparities. <strong>The</strong> availability of highqualitychild care is critical when parents work outsidethe home.• About half of the nation’s 2-year-olds are in somekind of regular, nonparental day care, split amongcenter-based care; home-based, nonrelative care;and home-based relative care. Black children arethe most likely to be in day care.• Overall, 24 percent of U.S. children were in centerbasedcare that was rated as high quality, 66 percentwere in medium-quality center-based care, and 9percent were in low-quality center-based care. Ofthose in home-based care, 7 percent were in highqualitysettings, 57 percent were in medium-qualitysettings, and 36 percent were in low-quality care.More than half of Black, Hispanic, and poor 2-yearoldswere in low-quality home-based care.<strong>The</strong> Home as an Educational Resource. <strong>The</strong>resources available at home — books, magazines,newspapers, a home computer with access to theInternet, a quiet place for study — can have a lastinginfluence on a child’s ability to achieve academically.• As of 2003, 76 percent of U.S. children hadaccess to a home computer, and 42 percent usedthe Internet. Black and Hispanic children laggedbehind, however.• Eighty-six percent of U.S. eighth-graders reportedhaving a desk or table where they could study, justabove the international average but well below theaverages of many countries.• Thirty-five percent of eighth-graders watch four ormore hours of television on an average weekday.Comparisons by race/ethnicity reveal considerabledifferences in viewing habits: 24 percent of Whiteeighth-graders spend at least four hours in front ofa television on a given day, while 59 percent of theirBlack peers do so.• A comparison of eighth-graders in 45 countriesfound that U.S. students spend less time readingbooks for enjoyment and doing jobs at home thanstudents in the average country participating in thestudy. On the other hand, U.S. eighth-graders spentmore time, on average, watching television andvideos, talking with friends, and participating insports activities. <strong>The</strong>y also spend almost one morehour daily using the Internet.• One in five students misses three or more days ofschool a month. Asian-American students have thefewest absences. <strong>The</strong> United States ranked 25th of45 countries in students’ school attendance.<strong>The</strong> Parent-<strong>School</strong> Relationship. A significant bodyof research indicates that when parents, teachers, andschools work together to support learning, studentsdo better in school and stay in school longer. Parentalinvolvement in student education includes everythingfrom making sure children do their homework,to attending school functions and parent-teacherconferences, to serving as an advocate for the school,to working in the classroom. How involved are parentsin their children’s education? Are schools helping tofacilitate parental involvement, and doing what theycan to effectively partner with parents?• Since 1996, parents have become increasinglyinvolved in their child’s school. However, parentparticipation decreases as students progressthrough school, and parents of students earning Aaverages are more likely to be involved in schoolfunctions than the parents of students earning C’sand D’s.Putting It Together: Estimating the Impact of<strong>Family</strong> and Home on Student Achievement.How closely can stars in this constellation of factorsassociated with a child’s home environment predictstudent achievement?• <strong>The</strong> analysis provided here uses four family/homefactors that previous research has shown to belinked to student achievement. To some degree,each is likely to be related to the others: singleparentfamilies, parents reading to young childrenevery day, hours spent watching television, and thefrequency of school absences.

• Together, these four factors account for abouttwo-thirds of the large differences among statesin National Assessment of Educational Progress(NAEP) eighth-grade reading scores.* * * * *<strong>The</strong> nation has set high goals for raising studentachievement. <strong>School</strong>s play a critical role in this effort,and it is appropriate that a serious national effortis being made to improve them. However, familycharacteristics and home environment play critical rolesas well. Reaching our ambitious national goals willrequire serious efforts to address issues on both fronts.

IntroductionRecognizing the family as the basic socializing andnurturing institution for children is intuitive. Commonsense tells us that the love and attention that babiesand children receive, their sense of security, theencouragement they are given to learn, the intellectualrichness of their home environment, and the attentionthat is devoted to their health and welfare are allcritical elements in the development of children whoare able and motivated to learn. Ironically, however,something so plain and obvious is often overlooked— or taken for granted.Even though public officials, PTA speakers,educators … often tell us how important arole the family plays, this message does nottranslate to a national resolve to improve thefamily as an educational institution.Thus began our 1992 report, America’s <strong>Smallest</strong><strong>School</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Family</strong>. 2 Although the critical importancechildren’s families play in their lives in the yearspreceding school, during the hours before and afterthe school day, and throughout the days, weeks,and months of summer and holiday breaks remainsapparent, it also stays largely outside current local,state, and national education policy discussions. <strong>The</strong>purpose of this report is to examine information andevidence regarding the critical role the family plays inthe education of the nation’s children.Over the past 15 years, state and national effortsto raise student achievement and reduce achievementgaps have intensified. <strong>The</strong> public and public officialstake the issue of improving education seriously, as isstrongly evidenced by the prominence of the No ChildLeft Behind (NCLB) Act in the national policy agenda.NCLB includes requirements for schools to promoteand facilitate stronger school-parent partnerships.Since America’s <strong>Smallest</strong> <strong>School</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Family</strong> waspublished, not much seems to have changed withrespect to the importance public policy gives to thefamily’s role in children’s learning, even as efforts haveintensified to raise student achievement and reduceachievement gaps. Nor has there been much progresstoward improving many of the conditions that weredescribed in that report. <strong>The</strong>re are, to be sure, effortsto promote the value of early childhood education,new commission reports, and more national leaderspushing for universal pre-kindergarten programs.<strong>The</strong>se efforts all stem from an explicit recognitionof the need to supplement family efforts if we are tosucceed in improving student learning and reducingachievement gaps.A new report card by UNICEF on the state ofchildhood in the world’s economically advancednations paints a bleak picture for the future ofeducation in the United States. In the report, UNICEFcompared the United States with 20 other richcountries on their performance in six dimensionsof child well-being. <strong>The</strong> United States ranks in thebottom third of these 21 countries for five of these sixdimensions. It ranked 12th in educational well-being,17th in material well-being, 20th in family and peerrelationships, 20th in behaviors and risks, and 21st inhealth and safety. 3Despite these disturbing findings, one can findmany good examples of efforts to promote strongerfamily involvement in children’s education, and thisreport describes some of these. Although our review ofcurrent literature identifies many other constructiveefforts to improve family and home conditionsassociated with child development, no major effortswere found to raise the prominence of “before-school”and “after-school” issues, identified in this report, inthe very visible state and national efforts to increaseachievement and reduce achievement gaps.This report is about the family, not about theschools, except in those critical areas where thefamily and school must work together. That said, theauthors have no intention of minimizing the needfor improving our nation’s schools — and it would bea misuse of the report’s findings to argue that all ofthe responsibility for educational improvement restsoutside of the schools. Indeed, a number of <strong>ETS</strong> PolicyInformation Center reports have argued that both areimportant in raising achievement and reducing gaps.A comprehensive review of the available facts andevidence on this subject is Parsing the AchievementGap: Baselines for Tracking Progress. 42Paul E. Barton and Richard J. Coley, America’s <strong>Smallest</strong> <strong>School</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Family</strong>, Policy Information Report, Policy Information Center,Educational Testing Service, 1992.3See UNICEF, Child Poverty in Perspective: An Overview of Child Well-Being in Rich Countries, Innocenti Report Card 7, 2007.4Paul E. Barton, Parsing the Achievement Gap: Baselines for Tracking Progress, Policy Information Report, Policy Information Center, EducationalTesting Service, October 2003.

It is understandable that education reform effortswould focus on improving schools. In the broaderarena of public policy, however, we will have to go farbeyond this focus if we hope to significantly improvestudent learning and reduce the achievement gap.This report highlights some of the important familycharacteristics and home conditions that researchhas found makes a significant difference in children’scognitive development and school achievement.Because the home is, indeed, “America’s smallestschool” — though clearly not its least significant one— it behooves us to take whatever steps are necessaryto assure the homes of all of our nation’s students canprovide the critical support children need to achieve. Ifwe are to improve America’s academic standing withinthe global community, and close our all-too-persistentachievement gaps, we must help ensure nurturinghome environments and supportive, encouragingfamily lives for all students.This is by no means a small endeavor. It will requirepolicy reform, government and social interventions,and above all, cooperative partnerships amongschools, families, and communities.* * * * *<strong>The</strong> report is organized as follows:<strong>The</strong> Parent-Pupil Ratio. Research indicates anupward trend in single-parent families and largedifferences in family-composition trends acrossracial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups. <strong>The</strong> reportexamines these changing patterns and explains howthey may be leading to a “new inequality.”<strong>Family</strong> Finances. Many families are stretched thin inmeeting the basic needs that will help children becomesuccessful students. <strong>The</strong> report looks at economictrends related to child poverty, parent employment,and food insecurity.Literacy Development. Children’s experiences duringthe first years of their lives — their interactions withthe people and world around them — are criticalto their future learning. <strong>The</strong> report examines thedifferences in early language development and schoolreadiness among children of different populationsubgroups. <strong>The</strong> authors also discuss how reading toyoung children influences their language development.<strong>The</strong> Extended <strong>Family</strong>: <strong>The</strong> Child Care Dimension.<strong>The</strong> report looks at the wide variety of child careavailable to parents, and the vast differences in thequality of that care.<strong>The</strong> Home as an Educational Resource. A homeenvironment that is conducive to learning is criticalto children’s ability to succeed in school. <strong>The</strong> authorsexamine the importance of resources and conditions thatsupport learning in the home (e.g., appropriate readingmaterials, a home computer with access to the Internet,and a quiet place to study). <strong>The</strong> authors also look atconditions that can distract students from learning, suchas spending too much time watching television, playingcomputer games, and surfing the Internet. Finally, theauthors examine trends related to these factors acrossdifferent racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups.<strong>The</strong> Parent-<strong>School</strong> Relationship. <strong>The</strong> authorsexamine why it’s important for parents to be involved intheir children’s school and to take a proactive approachto encouraging their children’s learning efforts. <strong>The</strong>authors then highlight trends in these behaviors.Putting It Together: Estimating the Impact of<strong>Family</strong> and Home on Student Achievement. <strong>The</strong>authors explore how a constellation of family andhome characteristics can be used to predict studentachievement.Concluding Comments. <strong>The</strong> authors discuss what familytrends imply about the future state of student learningin the United States. <strong>The</strong>y then elaborate on the need toimprove conditions in both the home and the school.* * * * *This report is packed with statistics and researchfindings, and the authors have drawn upon manysources — from small research studies, to nationalcensuses and data bases, to international surveys.Readers will have different interests, differentperspectives, and different needs. <strong>The</strong> authors hopethat the information in this publication will be helpfulto a diverse audience — an audience with a commoninterest in improving student learning and reducingachievement gaps.

<strong>The</strong> Parent-Pupil RatioOur society relies on parents to nurture and socializechildren. It follows then that having two parentsparticipating in the child-rearing effort is better thanhaving just one, even if only from the standpoint oflogistics and time: time to talk with children, read tothem, help them with homework, get them up and offto school, check their progress with their teachers, andso on.Two-parent families are more likely than singleparentfamilies to be participating in the workforceand to have middle-class incomes. Today, having a“decent” family income is more dependent than everon having two parents working. Families headed onlyby mothers — as the majority of single-parent familiesare — have, on the average, much lower incomesand fewer benefits that go along with employment(such as medical insurance) than two-parent families.Adequate housing, medical care, and nutritioncontribute to children’s cognitive development andschool achievement. 5 While logic, common sense,and research all lead to the conclusion that childrengrowing up with one parent may have a disadvantage,it is often not an easy subject to discuss.What Research RevealsDespite continuing sensitivity about the topic, thereis a growing body of research on family structure andits relationship to children’s well-being. While theresearch generally focuses on whether a child liveswith one versus two parents, there is some researchon the effects of mother-only families; some researchon children with divorced parents; some on childrenwith young, unmarried parents; and some researchthat focuses on the effects on children of growing upwith absent fathers. <strong>The</strong> first comprehensive reportingof this research was undertaken by a committee of theNational Research Council (NRC), which synthesizedand cited more than 70 studies published between 1970and 1988. <strong>The</strong> NRC concluded that:High rates of poverty, low educationalperformance, and health problems are seriousobstacles to the future and well-being ofmillions of children. <strong>The</strong> problems are muchmore acute among black children …. <strong>The</strong>disadvantage of black children relative towhite children is due almost entirely to the lowincome of black family heads … Approximatelyone-half of black children have the additionalburden of having mother-only families. Manybegin life with an under-educated teenagemother, which increases the likelihood thatthey will live in poverty and raises additionalimpediments to their life prospects. 6<strong>The</strong> most recent and large-scale synthesis ofresearch on single-parent families in the United Statesis “Father Absence and Child Well-Being” by WendySigle-Rushton and Sara McLanahan, who start withthis overview:Cohabitation has replaced marriage asthe preferred first union of young adults;premarital sex and out-of-wedlock childbearinghave become increasingly commonplace andacceptable; and divorce rates have recentlyplateaued at very high levels. One out of threechildren in the United States today is bornoutside of marriage, and the proportion istwice as high among African Americans. 7Researchers must consider several issues whenassessing the impact growing up in a single-parentfamily can have on children’s academic success. Firstthey need to determine whether children raised insingle-parent households are different from those whogrow up with two parents in the home in ways thataffect learning and academic success. And, if they do,researchers need to then clarify how they differ. <strong>The</strong>ymust then disentangle the factors that contribute tothese differences, which involve separating factorsrelated to low income from those that are entirelydue to a growing up in a single-parent family. Whileresearch can illuminate issues related to income, it’sfar more difficult to find scientific evidence of theeffect growing up in a single-parent household has on5For a synthesis of research on such family factors, see Barton, 2003.6Gerald David Jaynes and Robin M. Williams, Jr. (Eds.), A Common Destiny: Blacks and American Society, National Research Council,National Academy Press, 1989.7Wendy Sigle-Rushton and Sara McLanahan, “Father Absence and Child Well-Being,” in Daniel P. Moynihan, Timothy M. Speeding, and LeeRainwater (Eds.), <strong>The</strong> Future of the <strong>Family</strong>, Russell Sage Foundation, 2004, p. 116.

learning. We can, however, identify with considerableconfidence the overall effects — always bearing inmind that we are talking about averages, not individualsituations. 8Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan summarize theresults of the simple correlations, which “can easily beinterpreted as the probability that a random person,drawn for a given family structure, will experience theoutcome of interest.” <strong>The</strong>y summarize the results oftheir research as follows:• Academic Success. “Studies demonstrate quiteconclusively that children who live in single-motherfamilies score lower on measures of academicachievement than those in two-parent families.”<strong>The</strong> differences are substantial (in statisticalterms, about a third of a standard deviation aftercontrolling for age, gender, and grade level).• Behavioral and Psychological Problems. Fatherabsence is correlated with a higher incidence ofbehavioral and psychological problems that mayinclude shyness, aggression, or poor conduct.• Substance Abuse and Contact With Police.Father absence is correlated with a greater tendencyto use illegal substances, have early contact with thepolice, and be delinquent.• Effect on Life Transitions. Daughters who growup in single-parent families are likely to havesexual relationships at an earlier age than thoseraised from two-parent homes, and are more likelyto bear children outside of marriage. <strong>The</strong>ir earlypartnerships also tend to be less stable.• Economic Well-Being in Adulthood. Researchhas established a strong link between growing upin a single-mother family and having lower incomeas adults.• Adult Physical Health and Psychological Well-Being. Adults from single-mother families havelower self-esteem than those growing up in twoparenthouseholds. Among women, research revealsa negative correlation between poor adult physicalhealth and growing up with a divorced mother. 9While, at first glance, all of these issues may notseem to be related to school achievement, each(e.g., delinquent behavior, drug use, and aggressivebehaviors) can adversely affect school achievement.And although these behaviors appear to be separateand distinct issues, they are often related, with onecondition resulting in another.Evidence also links these variables to other schoolproblems. For example, a Bureau of the Censuspublication reports that the percentage of schoolagechildren of never-married parents were morethan twice as likely to repeat a grade than childrenof married parents (21.1 percent compared to 8.4percent, respectively); the percentage for children ofseparated, divorced, or widowed parents was 13.4percent. Very similar differences were found for thepercentage of children who were ever suspended fromschool. And for both repeating a grade and beingsuspended from school, the rates were much higherfor children in families living below the poverty linethan for children living above it. 10A recent report from the <strong>ETS</strong> Policy InformationCenter found a close relationship between states’ highschool completion rates and the percentage of childrenliving in one-parent families, after controlling forsocial economic status (SES). <strong>The</strong> single-parent familyfactor, by itself, explained over a third of the variationin high school completion rates (SES, single-parentfamilies, and high student mobility together explainedalmost 60 percent of the variation). 11 Another recent<strong>ETS</strong> analysis found that the variation among the statesin the prevalence of one-parent families had a strongcorrelation with the state variation in eighth-gradereading achievement. 128On this matter of disentangling effects, and for a comprehensive look at marriage and children, see the fall issue of <strong>The</strong> Future of Children(titled “Marriage and Well-Being”) published by the Brookings Institution (www.futureofchildren.org).9Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan, 2004.10Jane Lawler Dye and Tallese D. Johnson, A Child’s Day: 2003 (Selected Indicators of Child Well-Being), Current Population Reports, p. 70-109,U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C., January 2007.11Paul E. Barton, One-Third of a Nation: Rising Dropout Rates and Declining Opportunities, Policy Information Report, Policy InformationCenter, Educational Testing Service, February 2005.12Paul E. Barton and Richard J. Coley, Windows on Achievement and Inequality, Policy Information Report, Policy Information Center,Educational Testing Service, 2007.

Having documented the correlation between havingtwo parents and student educational achievement, thissection now examines data on parenthood trends inthe United States.Out-of-Wedlock BirthsOf the 2.3 million births to women under age 30 in 2003-04, about 1 million (or 44 percent) were to unmarriedwomen. Figure 1 shows the percentage of out-of-wedlockbirths for women in each racial/ethnic group.Figure 1Percentage of Out-of-Wedlock Births to WomenUnder Age 30, by Racial/Ethnic Group, 2003-2004AllBlackMixed RaceHispanic44466077higher were out-of-wedlock; this was also the case for 43percent of births to Hispanic mothers. 13Figure 2Percentage of Out-of-Wedlock Births to WomenUnder Age 30, by Educational Attainment of theMother, 2003-2004AllLess thanhigh schoolHigh schooldiploma or GEDSome collegeBachelor’s degreeMaster’s degreeor more413370 10 20 30 40 50 60 70Percentage445162WhiteAsian1634Source: Data from 2004 American Community Surveys reported in Irwin Kirsch, HenryBraun, Kentaro Yamamoto, and Andrew Sum, America’s Perfect Storm: Three ForcesChanging Our Nation’s Future, Policy Information Report, Policy Information Center,Educational Testing Service, January 2007.0 20 40 60 80 100PercentageSource: Data from 2004 American Community Surveys, reported in Irwin Kirsch, HenryBraun, Kentaro Yamamoto, and Andrew Sum, America’s Perfect Storm: Three ForcesChanging Our Nation’s Future, Policy Information Report, Policy Information Center,Educational Testing Service, January 2007.<strong>The</strong>se data paint a grim picture of the status ofmarriage and childbirth in the United States. Seventysevenpercent of Black, 60 percent of mixed-race, and46 percent of Hispanic births were out-of-wedlock. Mostof these out-of-wedlock births were to women with lowlevels of educational attainment. As shown in Figure2, overall, the proportion of out-of-wedlock births fallssubstantially with each additional level of educationmothers attain. <strong>The</strong> proportions are higher, however, forsome groups. Among Black mothers, for example, morethan half of births to those with a bachelor’s degree orIt’s important, however, to understand that thisdichotomy between in- and out-of-wedlock birthsoversimplifies the variation of family types. Accordingto the demographer, Harold Hodgkinson:Four million children of all ages now live withone or more grandparents, and one millionchildren of all ages are the sole responsibility oftheir grandparents … A number of factors havecreated this group, such as parents who are injail, in drug rehabilitation centers, or those whosimply are not capable of raising their children.<strong>The</strong> problems of raising young children whenyou are 65 years old are severe — yet, for manygrandparents there is no alternative.<strong>The</strong> Statistical Abstract of the United States,2002, indicates the following family types wereraising children under 18 years old: 46 percent13American Community Survey data, reported in Kirsch, Braun, Yamamoto, and Sum, 2007.10

of married couples; 43 percent of unmarriedcouples; 60 percent of single women; 22percent of gay couples; and 34 percent oflesbian couples. Several of these categoriesare new for the Census … and little is knownabout how many children are being raised byeach type. However, many teachers report anincrease in the number of children being raisedby same-sex couples. 14Number of Parents in the HomeWhat is the trend for children living in two-parentfamilies in the United States? In the nation as a wholein 2004, 68 percent of children were living with bothparents, down from 77 percent in 1980. <strong>The</strong>re weresubstantial declines among the White, Black, andHispanic populations of children with two parents inthe home over that period, as shown in Figure 3. <strong>The</strong>lowest percentage of children living with two parentswas among Black children — just 42 percent in 1980,dropping to 35 percent in 2004. Thus, the majority ofBlack children live in single-parent homes.Figure 3Percentage of Children Under Age 18 Living WithBoth Parents, by Race/Ethnicity, 1980 and 2004Percentage80706050403077688374 75’80 ’04 ’80 ’04 ’80 ’04 ’80 ’04All White Hispanic BlackSource: U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States, Table 60, June 29, 2005.654235Figure 4Percentage of Children in Single-Parent Families,by State, 2004UtahIdahoNebraskaIowaKansasMinnesotaNorth DakotaNew JerseyColoradoIndianaNew HampshireVermontConnecticutMontanaSouth DakotaWyomingHawaiiIllinoisWisconsinCaliforniaMassachusettsOregonVirginiaWest VirginiaAlaskaKentuckyPennsylvaniaWashingtonU.S.ArizonaMichiganMissouriNevadaTexasMaineMarylandOhioNew YorkNorth CarolinaOklahomaTennesseeDelawareGeorgiaAlabamaFloridaArkansasNew MexicoRhode IslandSouth CarolinaMississippiLousiana1723232424242425262626262727272728282829292929293030303031313131313233333334343434353536363838394042440 10 20 30 40 50 60 70PercentageSource: Data on one-parent families from Kids Count State-Level Data Online (www.aecf.org/kidscount/sld/compare_results.jsp?i=721).14Harold L. Hodgkinson, Leaving Too Many Children Behind: A Demographer’s View on the Neglect of America’s Youngest Children, Institute ofEducational Leadership, April 2003.11

<strong>The</strong> variation among the states in the percentageof single-parent families is considerable, as shown inFigure 4. <strong>The</strong> low is 17 percent in Utah, while SouthCarolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana have percentagesof 40 or higher.A comparison among large cities is shown inFigure 5. San Diego and Austin had the lowestpercentages of children in one-parent families,although about one-third of families fall into thiscategory. Atlanta and Cleveland had the highestpercentages of single-parent families, with about twothirdsof the cities’ families falling into this category.International comparisons are also available,although there are variations in the years for whichdata are available. In comparison with nine othercountries where data were available, the United Stateshad the highest percentage of one-parent families (28percent) and Japan the lowest (8 percent). <strong>The</strong>re weresubstantial increases in all countries in this statistic forthe time periods available (see Figure 6). In addition,Figure 5Percentage of One-Parent Families,Selected Cities, 2004San DiegoAustinLos AngelesHoustonCharlotteNew YorkChicagoBostonClevelandAtlanta3133363638434552636630 40 50 60 70PercentageSource: U.S. Census Bureau, 2005 American Community Survey.Figure 6Change in the Percentage of Single-Parent Households, Selected Countries, Various Years3530282524Percentage2015105201115201320720141913191217915580’80 ’03 ’85 ’02 ’91 ’04 ’80 ’05 ’81 ’04 ’81 ’03 ’81 ’01 ’88 ’00 ’81 ’04 ’80 ’00United StatesSwedenGermany (unified)DenmarkIrelandUnited KingdomCanadaFranceNetherlandsJapanNote: Data are for children under 18 (except for Australia and Ireland, where data are for children under 15).Source: Compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics from national population censuses, household surveys, and other sources. Some data are fromunpublished tabulations provided by foreign countries (www.childstats.gov/intnllinks.asp?field=Subject1&value=Population+and+<strong>Family</strong>+Characteristics).12

for most of the countries included in this comparison,about one-fifth of families with children were singleparentfamilies. It is clear that the phenomenon of arising rate of children living with one parent is by nomeans confined to the United States.<strong>The</strong> New Inequality<strong>The</strong> nation is very familiar with inequality based onrace/ethnicity and income. Reducing and eliminatingachievement gaps is national policy in education,and NCLB puts teeth into this policy by requiring thedisaggregation of test scores by race/ethnicity andpoverty. It is time to recognize that there is anotherform of inequality in the circumstance of growing upand getting educated: It is whether a child grows upwith two parents in the home, or one. (Once again, it isimportant to understand that the authors are speakingin terms of averages.)This form of inequality cuts across racial andethnic subgroups and family income status. However,it is disproportionately concentrated in minorityand low-income populations. For example, as Figure3 shows, more than half of Black children are notliving with two parents. Efforts to compensate for thedisadvantages children experience when growing upin homes lacking the personal and economic resourcesto support their learning will disproportionatelybenefit students in minority and poor families. Iflow income were combined with not living with twoparents — recognizing the double deficit — minoritystudents would predominate in any targeted effort tocompensate for deprivations and life conditions ofthe kind that have been shown to hinder educationalachievement. <strong>The</strong> next sections of the report identifysome of the family and home conditions that canaffect educational achievement.13

<strong>Family</strong> FinancesMost agree that schools must be adequately fundedif they are to educate students successfully, althoughthere continues to be significant disagreementover how much funding is sufficient. Families alsorequire resources to function effectively as educatinginstitutions, although it’s difficult to pin down exactlywhat constitutes “adequate resources.”<strong>The</strong> report does not argue that lower incomealone is the source of educational inadequacies in thefamily, just as its authors would not argue that a lowerschool budget in itself can be blamed for low studentachievement. In fact, the premise of our 2003 report,Parsing the Achievement Gap, was that it was necessaryto “decompose” income, examining the conditions andbehaviors that are shown by research to be correlatedwith school achievement – which may or may not be“determined” by how much money the family has.<strong>The</strong> most thorough examination of the effectsof family income on the success of children wasperformed by Susan E. Mayer. She cautions aboutascribing “causation” to simple statistical correlations,and in her analysis sorts out what can be attributedto income alone. While she does find a relationshipbetween family income and success, she says itis smaller than generally thought to be. Also, shesuggests that the attributes that make parentsattractive to employers may be similar to those thatmake them good parents. 15In Parsing the Achievement Gap, we identifiedfactors and conditions, which did not include income,that were related to achievement. <strong>The</strong>n we lookedat how the factors differed in high- and low-incomefamilies. <strong>The</strong> gaps in these factors mirrored the gaps inachievement between children in high- and low-incomefamilies. Examples of these factors were birthweight,changing schools, and reading to young children.This report also highlights ways families cansupport and encourage learning that do not dependdirectly on financial resources. <strong>The</strong>se include settingtime limits on watching TV, reading to children, andmaking sure that they get to school. Unfortunately,some important learning supports do require money— and not just nickels and dimes. It takes financialresources to buy books for children to read, shoes forthem to wear to school, and a quiet place for themto read and study. And, more so than parents withsalaries, parents who earn hourly wages may findit difficult (and cost-prohibitive) to take time off toattend a parent-teacher conference or to do volunteerwork at school.Still other important supports for educationaldevelopment involve substantial resources:nutritious food, adequate clothing, glasses to correcta child’s vision problems, and treatment for children’shealth problems. Research has shown that these allaffect student learning and school attendance. Safetynet programs may make a considerable difference,of course, in helping families meet such needs.However, there are large holes in the net, and manyfamilies may not have the knowledge and ability toaccess these programs.Another problem many families in economic straitsface is the need to move from one place to another tofind jobs and affordable housing. This often meansthat their children will have to change schools as well— and that’s a problem, since research has shownthat changing schools frequently can have a negativeimpact on student achievement.<strong>The</strong> United States has the greatest inequality in thedistribution of income of any developed nation — aninequality that has been rising decade by decade. In2004, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau,the top and most affluent quintile (or fifth) had 50percent of the aggregate household income, while thebottom and poorest quintile had 3.4 percent of theincome. Put another way, the top-income householdshad more than 14 times more income than thebottom-income households. 16 As New York Timescolumnist Paul Krugman writes: “We’ve gone back tolevels of inequality not seen since the 1920s.” 17This section provides several measures of familyfinancial resources and examines the distribution ofthose resources among population subgroups andamong the states. <strong>The</strong> authors examine median family15Susan E. Mayer, What Money Can’t Buy: <strong>Family</strong> Income and Children’s Life Chances, Harvard University Press, 1997.16Carmen DeNavas-Walt, Bernadette D. Proctor, and Cheryl Hill Lee, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States:2005, U.S. Census Bureau, August 2005.17“Gilded No More,” <strong>The</strong> New York Times, April 27, 2007.14

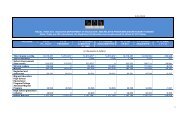

income, the proportion of children who live in poverty,and the proportion who live in families where parentemployment is unstable.While it is hard to disentangle the effects of incomefrom other characteristics associated with social class,it is clear that children from poor families often missout on many enriching extra-curricular activities thattheir more affluent peers participate in. For example,only 20 percent of school-age children in families withpoverty incomes take lessons of some sort, compared to31 percent of children in families at or above the povertyline. And only 23 percent of children in poor familiesbelong to clubs, compared to 36 percent of childrenwhose families are at or above the poverty line. 18Median <strong>Family</strong> IncomeLarge differences exist across states and populationsubgroups on any measure of income. Here we focuson the median income of families with children underage 18 in the household, and show the variationsacross states and among racial/ethnic groups. Table 1shows the 2005 median income for families with andwithout children, by racial/ethnic groups.Table 1Median <strong>Family</strong> Income for FamiliesWith and Without Children, 2005TotalIncomeWithChildrenNoChildrenAll $56,194 $55,176 $57,258White, not Hispanic 63,156 66,235 60,979Black 35,464 31,705 42,079Asian American 68,957 70,292 67,087Hispanic 37,867 36,403 41,276Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2006 Annual Social and EconomicSupplement (http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032006/faminc/new03_000.htm).As Table 1 shows, there are large income differencesamong racial/ethnic groups. On average, Asian-American families have the highest incomes and Blackfamilies have the lowest. <strong>The</strong> table also shows thatfamilies with no children have slightly higher incomes,on average, then those with children. <strong>The</strong>re are twonoticeable exceptions, however. White and Asian-American families with children have higher incomesthan White and Asian-American families with noFigure 7Median Annual <strong>Family</strong> Income for Families WithChildren, by State, 2005ConnecticutNew JerseyMarylandMassachusettsNew HampshireMinnesotaVirginiaAlaskaHawaiiDelawareIllinoisRhode IslandColoradoWisconsinMichiganVermontNew YorkWashingtonPennsylvaniaCaliforniaNebraskaIowaWyomingOhioNorth DakotaIndianaUtahKansasMaineNevadaGeorgiaSouth DakotaMissouriOregonFloridaArizonaNorth CarolinaIdahoSouth CarolinaTennesseeKentuckyTexasMontanaLouisianaAlabamaOklahomaArkansasWest VirginiaNew MexicoMississippiD.C.76,26676,12074,66972,27970,40365,16264,41463,08362,48861,70860,39360,23058,41658,34857,00956,79956,68056,46256,36256,29155,01854,99253,72253,54353,32352,74451,98851,74551,70551,35651,26951,07750,96649,93449,12647,40646,48646,32046,12445,89745,27445,08144,81543,31643,09442,31141,12040,59839,27537,43336,27420 30 40 50 60 70 80Thousands of DollarsSource: Income data are from U.S. Census Bureau and the 2005 American CommunitySurvey.18Dye and Johnson, 2007.15

children. <strong>The</strong> opposite is true for Black and Hispanicfamilies: Those with children have lower averageincomes than their counterparts with no children.Large differences also show up across the states, asFigure 7 shows. Connecticut, New Hampshire, NewJersey, Maryland, and Massachusetts all have medianannual family incomes over $70,000, contrastingsharply with the median incomes in Mississippi andWashington, D.C., which are about half that of theaforementioned states.Children Living in PovertyAs Figure 8 shows, differences exist in poverty ratesamong families of different racial/ethnic groups. In2005, 11 percent of White children under the age of18 were living in poverty, as were 13 percent of Asian/Pacific Islander children. Those percentages increaseto 29 percent of Hispanic/Latino children, and toabout one-third of American Indian/Alaskan Nativeand Black children.Figure 8Percentage of Children in Poverty,by Racial/Ethnic Group, 2005BlackAmerican Indian/Alaskan NativeHispanic/LatinoU.S.Asian/Pacific IslanderWhite1311192932360 10 20 30 40 50PercentageSource: Poverty data are from the American Community Survey, reported in Kids CountState-Level Data Online (www.aecf.org/kidscount).Figure 9Percentage of Children in Poverty, by State, 2005New HampshireMarylandUtahWyomingConnecticutMinnesotaNew JerseyHawaiiNorth DakotaVirginiaColoradoDelawareIowaMassachusettsWisconsinAlaskaKansasNebraskaNevadaVermontWashingtonIllinoisIndianaMainePennsylvaniaFloridaIdahoOregonSouth DakotaU.S.CaliforniaMichiganMissouriNew YorkOhioRhode IslandArizonaGeorgiaMontanaNorth CarolinaTennesseeKentuckyOklahomaSouth CarolinaAlabamaArkansasTexasNew MexicoWest VirginiaLouisianaMississippi9111111121212131313141414141415151515151516171717181818180 10 20 30 40Source: Poverty data are from the American Community Survey, reported in Kids CountState-Level Data Online (www.aecf.org/kidscount).19191919191919202020212122232325252526262831PercentagePoverty is also spread unevenly around the country,as Figure 9 shows. While 9 percent of children in NewHampshire were living in poverty in 2005, 31 percentof Mississippi children were living in poverty.16

Food InsecurityDespite the existence of federal food aid programs,many U.S. families are unable to adequately feedeverybody in the family. According to the U.S.Department of Agriculture, 11 percent of U.S.households (12.6 million families) were classified as“food insecure” at some time during 2005. This meansthat these households, at some time during the year,were uncertain of having, or unable to acquire, enoughfood to meet the needs of all household membersbecause they had insufficient money or lacked otherfood resources.Good nutrition is vital for developing mindsand bodies. Researchers using the Early ChildhoodLongitudinal Study–Kindergarten Cohort toinvestigate the relationship of food insecurity toachievement found that kindergartners from less foodsecurehomes scored lower at the beginning of thekindergarten year than other children, and learned lessover the course of the school year. 19Figure 10 shows the percentage of households whowere food insecure in 2005 by demographic groups.<strong>The</strong> 11 percent average masks the disadvantagesexperienced by certain population subgroups.For example, nearly one-third of female-headedhouseholds were food insecure at some time during2005, triple the rate for married-couple families. <strong>The</strong>rate for Black households, at 22 percent, was nearlytriple the rate of White households. In addition, nearlyone-fifth of Hispanic households were food insecure.<strong>The</strong> government further breaks down the foodsecurity statistics on households having “low foodsecurity” (households able to obtain enough food byusing various coping strategies) and “very low foodsecurity” (households in which normal eating patternswere disrupted and food intake was reduced due toinsufficient money or other resources). In 2005,7 percent of U.S. households were classified as “lowfood security,” and 4 percent were classified as “verylow food security.” Again, it is important to rememberthat this combined 11 percent represents 12.6 millionhouseholds. 20Figure 10Prevalence of Food Insecurity by HouseholdCharacteristics, 2005*All householdsHousehold composition:Female head, no spouseOther household with child**Male head, no spouseWith children under age 6With children under age 18Married couple familiesRace/ethnicity:BlackHispanicOtherWhiteParent Employment0 10 20 30 40Percentage* Food insecurity is defined as households, at some time during the year, that were uncertainFoodof having,insecurityor unableis definedto acquire,as households,enoughatfoodsometo meettimetheduringneedstheofyear,all theirthatmemberswere uncertain ofbecausehaving, ortheyunablehadtoinsufficientacquire, enoughmoney orfoodotherto meetresourcesthe needsfor food.of all their members because they** had Households insufficient with money children or other in complex resources living for arrangements, food. e.g., children of other relativesor unrelated roommate or boarder.**Households with children in complex living arrangements, e.g., children of other relatives orSource: Data calculated by the Economic Research Service using data from the Decemberunrelated roommate or boarder.2005 Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement.As one would expect, families with low incomes willtypically be those that have had less success in thejob market. Of course, income can come from othersources, and for those most in need, a substantialportion will come from the safety-net programs,such as food stamps, unemployment insurance, andwelfare. Beyond providing a steady income, parentswho maintain steady employment also model sociallyresponsible behavior for children to follow.Figure 11 shows the percentage of children wholive in families where no parent has full-time, yearroundemployment, broken out by racial/ethnic group.Overall, these percentages are high, and for somegroups the rates are alarming. While 27 percent of81110101918171618223119Joshua Winicki and Kyle Jemison, “Food Insecurity and Hunger in the Kindergarten Classroom: Its Effect on Learning and Growth,”Contemporary Economic Policy, Vol. 21, No. 2, April 2003, pp. 145–157.20U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Food Security in the United States: Conditions and Trends (www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/FoodSecurity/trends.htm).17

White children live in families where neitherparent has full-time year-round employment,half of American Indian/Alaskan Native andBlack children and one-third of Hispanic childrenare in this situation.Figure 11Percentage of Children in Families Where NoParent Has Full-Time, Year-Round Employment,by Racial/Ethnic Group, 2005American Indian/Alaskan NativeBlackHispanic/LatinoU.S.Asian/Pacific IslanderWhiteSource: Employment data from the American Community Survey, reported in Kids CountState-Level Data Online (www.aecf.org/kidscount).Employment trends also vary significantly fromstate to state. Iowa, Nebraska, and Utah have thelowest percentage (26 percent) of children living infamilies where no parent has full-time, year-roundemployment. At the opposite end of the scale, onaverage, 43 percent of children in Mississippi live insuch a family. 21Taken together, the measures presented here painta bleak picture of family resources for many of thenation’s families — and the children in their care.While education and public policy generally givestrong support to improving student learning andreducing achievement gaps, the task of greatly raisingthe income floor or reducing economic inequalitythroughout the nation has not been addressed.Income inequality is growing in the United States, not2733323951500 10 20 30 40 50 60Percentagedeclining. But while national debates about incomeinequality become polarized, local pragmatic measuresmay resonate at the community level — measuresthat could help ameliorate the negative effects ofinadequate family income. <strong>The</strong>se measures couldfocus on specific identifiable needs and conditions thatare clearly involved in school achievement — reachingout beyond instruction in the classroom (in thetradition of the school lunch and breakfast programsthat recognize that hungry children can’t learn andthat nutrition is a factor in cognitive development).<strong>School</strong> systems and communities could developsystematic strategies to identify needs that caninfluence learning, and set about meeting those needs— aided possibly by higher levels of government. Howabout providing free books to impoverished families,or health exams along with necessary medical, dental,and vision care for conditions that affect achievement?Perhaps schools could provide students with their ownstudy spaces (with desks, computers, reference books,paper, and pencils) and offer after-school eveningmeals. A canvass across the nation would disclose avariety of approaches that are now being used to helpchildren. <strong>The</strong> programs and services already institutedin schools throughout the country offer a rich sourceof information and experience. 22But let us not forget the services already availablethat many families don’t take advantage of. Forexample, Medicaid now covers many children’s healthneeds, but many of the parents who qualify for theprogram haven’t enrolled their children. A first andvery productive step toward helping families supportand facilitate their children’s academic success wouldbe to educate parents about the programs and servicesavailable to help, and encouraging their use.21State employment data are from the American Community Survey reported in Kids Count State-Level Data Online (www.aecf.org/kidscount)22A central source of information is the Coalition of Community <strong>School</strong>s at the Institute for Educational Leadership.18

Literacy Development in Young ChildrenWe now have a good assessment of the achievement ofyoung children when they first enter the school system,thanks to the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study.Known as the ECLS-K, the study was conductedby the U.S. Department of Education’s NationalCenter for Education Statistics and began with thekindergarten class of 1998–99. Educators have longhad information about student achievement beginningat the fourth grade, through the National Assessmentof Educational Progress (NAEP). What hasn’t beenknown is: (1) how much of the achievement gap thatis observed among different groups of students at thefourth grade already existed when these students wereentering kindergarten, and (2) what are the factorsthat might be responsible for the early learning gaps?Many elements in the home environment influencecognitive development and learning. With ECLS-Kwe can now determine how large the achievementdifferences are in reading and mathematics amongstudents of different racial/ethnic groups and withdifferent levels of family socioeconomic status (SES)at the point of entry into formal schooling. FigureFigure 12Reading and Mathematics Achievement at theBeginning of Kindergarten, by Racial/Ethnic GroupAsianWhiteOtherHispanicBlackAsianWhiteBlackOtherHispanicMathematicsReading17.417.116.50 5 10 15 20 25 30IRT Scaled Test Score22.2Source: Valerie E. Lee and David T. Burkam, Inequality at the Starting Gate: Social BackgroundDifferences in Achievement as Children Begin <strong>School</strong>, Washington, D.C.: EconomicPolicy Institute, 2002.2119.919.919.523.225.712 shows the reading and mathematics scores ofbeginning kindergartners in the fall of 1998, by racial/ethnic groups. <strong>The</strong> data show substantial differencesin children’s reading and mathematics test scores asthey begin kindergarten. Average mathematics scoresare 21 percent lower for Black children than for Whitechildren. Hispanic children’s scores are 19 percentlower than the scores of White children. Similardifferences also exist in reading.Early Language AcquisitionWhile there have been many studies about whathappens in the early years of life and how earlyexperiences affect cognition and language acquisition,none has been as thorough as the work by Betty Hartand Todd Risley, who studied children’s languagedevelopment from birth through age 3. <strong>The</strong>seresearchers recorded and monitored many aspectsof parent-child interactions and noted the children’sprogress. <strong>The</strong>y found that in vocabulary, language, andinteraction styles, children mimic their parents.Hart and Risley observed that in working-classfamilies, “about half of all feedback was affirmativeamong family members when the children were 13 to18 months old; similarly, about half the feedback givenby the child at 35 to 36 months was affirmative.” Thatis, when the parents spoke in an affirmative mannerto a child, the child imitated this tone in talking tosiblings and parents. An affirmative tone was slightlymore prevalent among professional parents, and theirchildren shared this.Conversely, in families on welfare, verbalinteractions with the children were much more likelyto be negative and, in turn, the same was true of theinteractions of the child with the rest of the family.In the families on welfare, the researchers generallyfound a “poverty of experience being transmittedacross generations.” One example of the researchers’findings related to language exchanges is illustratedin Figure 13, which shows the estimated numberof words addressed to the children over 36 months,with the trends extrapolated through 48 months.<strong>The</strong> differences were huge among the professional,working-class, and welfare families. This researchindicates that, by the end of four years, the averagechild in a professional family hears about 20 million19

more words than children in working-class familieshear, and about 35 million more than the children inwelfare families hear. 23Figure 13Estimated Cumulative Differences in LanguageExperience by 4 Years of AgeEstimated Cumulative Words Addressed to Child(in millions)504030201000 21426348** Projected from 36 to 48 months.Source: Hart *Projected and Risley, from 1995. 36 to 48 months.Age of Child in MonthsReading to Young ChildrenProfessionalfamilyWorking-classfamilyWelfare familyChild Trends, a nonprofit, nonpartisan researchorganization dedicated to improving the lives ofchildren, sums up seven research papers, reports,and books, and cites 19 researchers to build anoverwhelming case for the value of reading to children:Children develop literacy-related skills long beforethey are able to read. By reading aloud to theiryoung children, parents can help them acquire theprerequisite skills they will need to learn to readin school. Being read to has been identified as asource of children’s early literacy development,including knowledge of the alphabet, print, andcharacteristics of written language.By the age of two, children who are readto regularly display greater languagecomprehension, larger vocabularies andhigher cognitive skills than their peers.Shared parent-child book reading duringchildren’s preschool years leads to higherreading achievement in elementary school,as well as greater enthusiasm for readingand learning. In addition, being read to aidsin the socioemotional development of youngchildren and gives them the skills to becomeindependent readers and to transition frominfancy to toddlerhood. 24Reading to children is about the simplest thingthat can be done to help them achieve, and it isa critical step in raising achievement and closingachievement gaps. For this reason, if for no other,teaching non-reading parents to read needs to be ahigh priority for communities, states, and the nation— as a key element of an education policy for children.Making sure all families have access to books andother suitable reading materials for their childrenmust also become a key part of this policy. Librarybookmobiles in poor areas, for example, could becomeas ubiquitous as the once-famous Good Humor man.<strong>The</strong>re is, of course, a considerable amount ofreading going on in the American family, although it isclear that the amount and quality varies considerably.For example, ECLS-K found a strong relationshipbetween a kindergartners’ SES and the extent to whichtheir parents read to them. As Figure 14 shows, at thehighest SES quartile, 62 percent of parents reportedreading to their children every day, compared to only36 percent of parents at the lowest SES quartile. <strong>The</strong>se25, 26are very large differences.Trend data displayed in Table 2 also show that, in2005, 60 percent of parents of 3- to 5-year-old childrenwho had not yet entered kindergarten read to theirchildren every day. In 1993, only 53 percent did so. Howmuch parent-to-child reading goes on in families variesa lot, depending on racial/ethnic group, SES, and family23Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children, Paul R. Brookes PublishingCo., 1995.24http://www.childtrendsdatabank.org/indicators/5ReadingtoYoungChildren.cfm25In statistical terms, this is a difference of about one-half of a standard deviation.26SES is measured from a scale that reflects the education, income, and occupations of kindergartners’ parents or guardians.20

Figure 14Percentage of Kindergartners Whose ParentsRead to <strong>The</strong>m Every Day, by Socioeconomic StatusHighest SESQuintilesLowest SES363925 35 45 55 65 75PercentageSource: Richard J. Coley, An Uneven Start: Indicators of Inequality in <strong>School</strong> Readiness,Policy Information Report, Policy Information Center, Educational Testing Service, March2002.structure variables. For example, in 2005, children inpoor families were less likely to have a parent read tothem regularly than children in more affluent families.And while 68 percent of White and 66 percent of Asian-American 3- to 5-year-olds were read to every day, thepercentage drops to 50 percent for Black children and45 percent for Hispanic children.<strong>Family</strong> characteristics also have an importantinfluence on learning and school success. As might beexpected, children in a two-parent family were morelikely to be read to than children in a single-parentfamily (63 percent vs. 53 percent). <strong>The</strong>re was also astrong relationship between mothers’ educational leveland the frequency of reading to the child. Seventytwopercent of children whose mothers were college414662Table 2Percentage of Children Ages 3 to 5 Who WereRead to Every Day in the Past Week by a <strong>Family</strong>Member, Selected Years, 1993-2005 271993 1995 1996 1999 2001 2005Total 53% 58% 57% 54% 58% 60%GenderMale 51 57 56 52 55 59Female 54 59 57 55 61 62Race and Hispanic OriginWhite, Non-Hispanic 59 65 64 61 64 68Black, Non-Hispanic 39 43 44 41 47 50Hispanic 28 37 38 39 33 42 45Asian American 46 37 62 54 51 66Poverty Status 29Below 100% poverty 44 47 47 39 48 50100-199% poverty 49 56 52 51 52 60200% poverty andabove 61 65 66 62 64 65<strong>Family</strong> TypeTwo parents 30 55 61 61 58 61 62Two parents, married - - - - 61 63Two parents,unmarried - - - - 57 50One parent 46 49 46 42 47 53No parents 46 52 48 51 53 64Mother’s Highest Level ofEducational Attainment 31Less than highschool graduate 37 40 37 39 41 41High schoolgraduate/GED 48 48 49 45 49 55Vocational/technicalor some college 57 64 62 53 60 60College graduate 71 76 77 71 73 72Mother’sEmployment Status 32Worked 35 hoursor more per week 52 55 54 49 55 57Worked less than35 hours per week 56 63 59 56 63 61Looking for work 44 46 53 47 54 63Not in labor force 55 60 59 60 58 65Source: Reproduced from the Federal Interagency Forum on Child and <strong>Family</strong> Statistics,America’s Children: Key Indicators of National Well-Being, 2006, Federal Interagency Forumon Child and <strong>Family</strong> Statistics, Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, TableED1. Based on National Household Education Survey analysis.27Estimates are based on children who have yet to enter kindergarten.28Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.29Poverty estimates for 1993 are not comparable to later years because respondents were not asked exact household income.30Refers to adults’ relationship to child and does not indicate marital status.31Children without mothers in the home are not included in estimates dealing with mother’s education or mother’s employment status.32Unemployed mothers are not shown separately but are included in the total.21

Figure 15Percentage of Children Who Were Read to EveryDay in the Past Week, 2003VermontMaineNew HampshireConnecticutMassachusettsMinnesotaPennsylvaniaColoradoOregonHawaiiWest VirginiaWashingtonRhode IslandWyomingDelawareIowaKentuckyVirginiaMarylandMichiganOhioMontanaKansasAlaskaNorth CarolinaNebraskaIdahoNew YorkIndianaU.S.North DakotaSouth CarolinaIllinoisMissouriD.C.New JerseySouth DakotaUtahWisconsinOklahomaOregonTennesseeCaliforniaArkansasArizonaFloridaNew MexicoAlabamaNevadaTexasLouisianaMississippi64615858575756565554545453535352515151515151505049494848484747474747474747464646454544434343434342413868graduates were read to daily, compared to 55 percentof children whose mothers were high school graduatesor who had obtained a GED, and 41 percent of childrenwhose mothers had not completed high school.<strong>The</strong>re is also considerable variation among thestates, as can be seen in Figure 15, which shows thepercentage of parents who read to their children,under age 5, every day. <strong>The</strong> low was Mississippi at 38percent, and the high was Vermont at 68 percent; thenational average was 48 percent.30 40 50 60 70PercentageSource: Data on reading to children are from Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative,National Survey of Children’s Health, Data Resource Center on Child and AdolescentHealth, 2005.22

<strong>The</strong> Child Care DimensionParents are children’s most important teachers duringtheir first five years of life. But parents are far frombeing children’s only teachers: A large proportion ofchildren are in the hands of child care providers for alarge amount of time. <strong>The</strong>se providers constitute thelarger family in which children are raised. It stands toreason, then, that improving the availability of highqualitychild care will improve student learning andreduce inequality.Research supports this assertion and is clearlysummed up in the Annie E. Casey Foundation 2006Kids Count essay:A large body of research underscores howquality child care enables young childrento build the cognitive and social skills thatwill help them learn, build positive socialrelationships and experience academic successonce they enter school. 33This <strong>ETS</strong> Policy Information Report has drawnheavily from the 2006 Kids Count essay, and the essayis an excellent synthesis of what is known and beingdone to improve child care.<strong>The</strong> Head Start program provides the mostconsistent model of quality child care available in theUnited States today. But for a variety of reasons, HeadStart and similar high-quality child care programsaren’t available to many families. Until quality childcare programs are accessible to all families, parentswill continue to rely on family members, friends, andneighbors to care for their children. Of 15.5 million U.S.children in child care today, some 6.5 million (almost42 percent) are in home-based settings. And 2.5 millionof these children come from families whose incomesare below 200 percent of the poverty line. AlthoughBlack families are the most likely to use home-basedcare arrangements, White families use them as well.Hispanic families are more likely to use parental care,but when they go outside the home for child care, theyturn to family members, friends, or neighbors for childcare rather than center-based care. 34Parents use family, friend, and neighbor care forreasons having to do with cost and inability to findtransportation to child care centers. Many parentswork shifts that don’t correspond to the hours childcare centers are available. Others choose this typeof care as a matter of preference based on issues oftrust, personal comfort, culture, and preferences for ahomelike environment. Says the Casey Foundation:This form of child care has been used forgenerations and will, undoubtedly, be animportant resource for years to come. For theforeseeable future, it will represent the mostcommon type of child care for low-incomechildren under age six whose parents areworking, especially those in entry-level jobswith non-traditional schedules. 35A Look at Day Care for the Nation’s 2-Year-OldsA longitudinal survey of children has recently releasedinformation on the child care arrangements for thenation’s 2-year-olds. <strong>The</strong> Early Childhood LongitudinalStudy, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), sponsored by theU.S. Department of Education’s National Center forFigure 16Regular Nonparental Care at About 2 Years of Age,by Primary Type of Care, 2003-04No regular care50.5%Center-based care15.8%Nonrelative care14.9%Relative care18.8%Source: Gail M. Mulligan and Kristin Denton Flanagan, Age 2: Findings from the 2-Year-OldFollow-Up of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), U.S. Departmentof Education, National Center for Education Statistics, August 2006.33Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2006 Kids Count Essay, 2006, (http://www.aecf.org/upload/PublicationFiles/2006_databook_essay.pdf).34Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2006.35Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2006.23