Improving Primary Health Care Through Collaboration: Briefing 2 ...

Improving Primary Health Care Through Collaboration: Briefing 2 ...

Improving Primary Health Care Through Collaboration: Briefing 2 ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

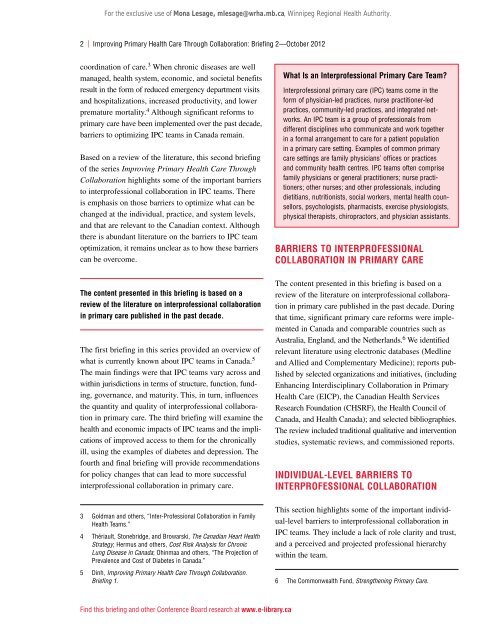

For the exclusive use of Mona Lesage, mlesage@wrha.mb.ca, Winnipeg Regional <strong>Health</strong> Authority.2 | <strong>Improving</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Through</strong> <strong>Collaboration</strong>: <strong>Briefing</strong> 2—October 2012coordination of care. 3 When chronic diseases are wellmanaged, health system, economic, and societal benefitsresult in the form of reduced emergency department visitsand hospitalizations, increased productivity, and lowerpremature mortality. 4 Although significant reforms toprimary care have been implemented over the past decade,barriers to optimizing IPC teams in Canada remain.Based on a review of the literature, this second briefingof the series <strong>Improving</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Through</strong><strong>Collaboration</strong> highlights some of the important barriersto interprofessional collaboration in IPC teams. Thereis emphasis on those barriers to optimize what can bechanged at the individual, practice, and system levels,and that are relevant to the Canadian context. Althoughthere is abundant literature on the barriers to IPC teamoptimization, it remains unclear as to how these barrierscan be overcome.What Is an Interprofessional <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Team?Interprofessional primary care (IPC) teams come in theform of physician-led practices, nurse practitioner-ledpractices, community-led practices, and integrated networks.An IPC team is a group of professionals fromdifferent disciplines who communicate and work togetherin a formal arrangement to care for a patient populationin a primary care setting. Examples of common primarycare settings are family physicians’ offices or practicesand community health centres. IPC teams often comprisefamily physicians or general practitioners; nurse practitioners;other nurses; and other professionals, includingdietitians, nutritionists, social workers, mental health counsellors,psychologists, pharmacists, exercise physiologists,physical therapists, chiropractors, and physician assistants.Barriers to InterProfessional<strong>Collaboration</strong> in <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Care</strong>The content presented in this briefing is based on areview of the literature on interprofessional collaborationin primary care published in the past decade.The first briefing in this series provided an overview ofwhat is currently known about IPC teams in Canada. 5The main findings were that IPC teams vary across andwithin jurisdictions in terms of structure, function, funding,governance, and maturity. This, in turn, influencesthe quantity and quality of interprofessional collaborationin primary care. The third briefing will examine thehealth and economic impacts of IPC teams and the implicationsof improved access to them for the chronicallyill, using the examples of diabetes and depression. Thefourth and final briefing will provide recommendationsfor policy changes that can lead to more successfulinterprofessional collaboration in primary care.The content presented in this briefing is based on areview of the literature on interprofessional collaborationin primary care published in the past decade. Duringthat time, significant primary care reforms were implementedin Canada and comparable countries such asAustralia, England, and the Netherlands. 6 We identifiedrelevant literature using electronic databases (Medlineand Allied and Complementary Medicine); reports publishedby selected organizations and initiatives, (includingEnhancing Interdisciplinary <strong>Collaboration</strong> in <strong>Primary</strong><strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> (EICP), the Canadian <strong>Health</strong> ServicesResearch Foundation (CHSRF), the <strong>Health</strong> Council ofCanada, and <strong>Health</strong> Canada); and selected bibliographies.The review included traditional qualitative and interventionstudies, systematic reviews, and commissioned reports.Individual-Level Barriers toInterprofessional <strong>Collaboration</strong>3 Goldman and others, “Inter-Professional <strong>Collaboration</strong> in Family<strong>Health</strong> Teams.”4 Thériault, Stonebridge, and Browarski, The Canadian Heart <strong>Health</strong>Strategy; Hermus and others, Cost Risk Analysis for ChronicLung Disease in Canada; Ohinmaa and others, “The Projection ofPrevalence and Cost of Diabetes in Canada.”5 Dinh, <strong>Improving</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Through</strong> <strong>Collaboration</strong>.<strong>Briefing</strong> 1.This section highlights some of the important individual-levelbarriers to interprofessional collaboration inIPC teams. They include a lack of role clarity and trust,and a perceived and projected professional hierarchywithin the team.6 The Commonwealth Fund, Strengthening <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Care</strong>.Find this briefing and other Conference Board research at www.e-library.ca