The other India - National Knowledge Commission

The other India - National Knowledge Commission

The other India - National Knowledge Commission

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

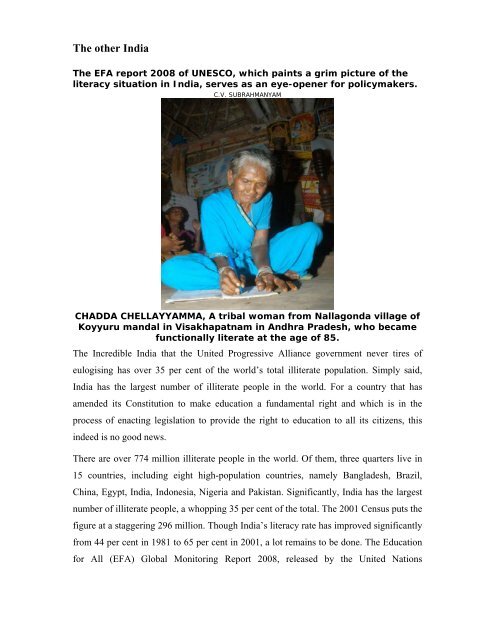

<strong>The</strong> <strong>other</strong> <strong>India</strong><strong>The</strong> EFA report 2008 of UNESCO, which paints a grim picture of theliteracy situation in <strong>India</strong>, serves as an eye-opener for policymakers.C.V. SUBRAHMANYAMCHADDA CHELLAYYAMMA, A tribal woman from Nallagonda village ofKoyyuru mandal in Visakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh, who becamefunctionally literate at the age of 85.<strong>The</strong> Incredible <strong>India</strong> that the United Progressive Alliance government never tires ofeulogising has over 35 per cent of the world’s total illiterate population. Simply said,<strong>India</strong> has the largest number of illiterate people in the world. For a country that hasamended its Constitution to make education a fundamental right and which is in theprocess of enacting legislation to provide the right to education to all its citizens, thisindeed is no good news.<strong>The</strong>re are over 774 million illiterate people in the world. Of them, three quarters live in15 countries, including eight high-population countries, namely Bangladesh, Brazil,China, Egypt, <strong>India</strong>, Indonesia, Nigeria and Pakistan. Significantly, <strong>India</strong> has the largestnumber of illiterate people, a whopping 35 per cent of the total. <strong>The</strong> 2001 Census puts thefigure at a staggering 296 million. Though <strong>India</strong>’s literacy rate has improved significantlyfrom 44 per cent in 1981 to 65 per cent in 2001, a lot remains to be done. <strong>The</strong> Educationfor All (EFA) Global Monitoring Report 2008, released by the United Nations

Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) in New Delhi recently,serves as an eye-opener for policy planners in <strong>India</strong>.Releasing the report, Koichiro Matsuura, Director-General of UNESCO, said:“Bangladesh, Pakistan and <strong>India</strong>, three highly populated countries, continue to face majorchallenges, in terms of both the high number of illiterates and the deep disparities thatexist between urban and rural areas. This poses a serious obstacle to national efforts toachieve Education for All and eradicate poverty.” What is of greater concern to <strong>India</strong> isthat its ranking has dipped by five since last year. It was ranked 100 out of 129 countriesin the EFA 2007 report. <strong>The</strong> EFA 2008 report places <strong>India</strong> at 105 out of 127 countries. Inall categories, whether it is enrolment at the primary level or gender parity or regionaldisparities, <strong>India</strong> finds itself at the bottom of the list, which mostly has countries fromsub-Saharan Africa. For instance, <strong>India</strong>, along with Nigeria and Pakistan, accounts for 27per cent of the world’s total out-of-school children. This translates to over 70 lakhchildren in <strong>India</strong> alone.At the World Education Forum in 2000, attended by 164 governments, 35 internationalinstitutions and 127 non-governmental organisations (NGOs), UNESCO adopted theDakar Framework for Action, promising to commit the necessary resources and efforts toachieve a comprehensive and inclusive system of quality education for all by 2015. <strong>The</strong>current EFA report marks the midway in the ambitious movement to expand learningopportunity to every child, youth and adult by 2015. In this context, the findings of thereport cause concern for <strong>India</strong> because it has pledged to put all children in the 6-14 agegroup in school by that time and attain over 85 per cent literacy rate.<strong>The</strong> UNESCO has defined six EFA goals:1. Expanding and improving comprehensive childhood care and education, especially forthe most vulnerable and disadvantaged children;2. Ensuring that by 2015 all children, particularly girls, children in difficult circumstancesand those belonging to ethnic minorities, have access to free and compulsory primaryeducation of good quality;3. Ensuring that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met throughequitable access to appropriate learning and life skills programme;

4. Achieving a 50 per cent improvement in levels of adult literacy by 2015, especially forwomen, and equitable access to basic and continuing education for adults;5. Eliminating gender disparities in primary and secondary education by 2005 andachieving gender equality in education by 2015; and6. Improving all aspects of quality of education and ensuring excellence of all so thatrecognised and measurable learning outcomes are achieved by all, especially in literacy,numeracy and essential life skills.On most of these counts, especially on universal primary education, gender parity andtotal literacy, <strong>India</strong> has already missed the bus. Efforts are on to improve the situation butthey are too slow, says the UNESCO report.<strong>The</strong> number of out-of-school children worldwide is 72 million. Though this is asignificant drop from the 96 million in 1999, it is large enough to cause concern,especially for <strong>India</strong>, which accounts for a substantial proportion of out-of-schoolchildren. It is difficult to imagine a scenario where all children of school-going age in<strong>India</strong> could be put in schools by 2015 as Prime Minister Manmohan Singh promisedduring the release of the EFA report.<strong>The</strong> EFA report says there has been an increase in the net enrolment rate of school-goingchildren at the primary level, but the dropout rate is high. <strong>The</strong> report attributes it to amultiplicity of reasons, mainly personal, financial, family or employment problems. Allthese coincide with children’s lack of confidence in the school’s ability to give themadequate support.However, it is significant that UNESCO has commended <strong>India</strong>’s effort in bringing suchchildren back into the sphere of education with parallel or non-formal systems ofeducation. It has especially mentioned the Open School System, which, combined with<strong>other</strong> literacy programmes, has served as an important agent of change. <strong>The</strong> EFA alsospeaks highly of <strong>India</strong>’s “revolution in distance education” and programmes such asSarva Shiksha Abhiyan and Mahila Samakhya, the latter with a special emphasis on girls.<strong>The</strong> report says <strong>India</strong>’s distance learning programme with EDUSAT, the world’s firstdedicated satellite for education, revolutionised the concept of distance education andcompensated for over 10,000 new schools by replacing them with virtual classrooms.

But the U.N. body makes it clear that these efforts are not enough, mainly because of thesheer increase in absolute numbers. <strong>India</strong> has already missed the 2005 target of achievinggender parity and will also miss the 2015 target of attaining total literacy. An<strong>other</strong>problem, highlighted by the EFA report, is the persistence of regional or geographicaldisparities in <strong>India</strong>, with States such as Kerala with high literacy rates at one end of thespectrum and those like Bihar with very low literacy rates at the <strong>other</strong> end. While manycountries have reduced this disparity substantially since 1999, there has been little changein the accessibility to schools in countries such as Benin, Bangladesh, Colombia,Ethiopia, Gambia, Kenya, Zambia, Zimbabwe and <strong>India</strong>.Yet an<strong>other</strong> highlight in the report is that disadvantaged sections of children, especiallyfrom rural areas and slums, continue to be deprived of education. This is worrisome for<strong>India</strong>, which has made universalisation of primary education one of its most ambitiousgoals; it is especially targeted at the disadvantaged sections of society.<strong>The</strong> EFA report also points at the continuing gender disparity in access to education. <strong>The</strong>sheer number of illiterate women in <strong>India</strong> is a matter of concern, despite somecommendable efforts by the government to improve women’s literacy. Though the reportspeaks highly of women-oriented programmes such as Mahila Samakhya and KasturbaBalika Vidyalaya, it points out that while girls’ enrolment at the primary level might haveincreased in <strong>India</strong>, their rate of survival until the secondary stage has remained poorowing mainly to household responsibility, especially sibling care.<strong>The</strong> report comes down heavily on the quality of education, too. It says “there is apressing need for significant improvement across the entire EFA spectrum”. In a nutshell,<strong>India</strong> has to perk up its performance regarding all the six EFA goals if it has to comeanywhere near its commitments.Remedial stepsSignificantly, what the UNESCO report has pointed out in such unambiguous terms hasbeen a matter of concern for educationists and social scientists in <strong>India</strong> for quite sometime. <strong>The</strong>y have been urging the government to take remedial steps, but to no avail. Forinstance, the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>Commission</strong>, headed by Sam Pitroda, has been writingconsistently to the Prime Minister for steps that need to be taken to improve the quality ofeducation, especially primary and secondary education. It has spelt out the “dos” for the

government that can go a long way in improving the quality of education in <strong>India</strong>,especially in view of the fact that the government is in the process of enacting the Rightto Education Bill.A letter from Sam Pitroda to the Prime Minister on October 20, 2007, says that Centrallegislation, despite concerns about federalism, is the only way to improve the quality ofeducation and make the right to education meaningful. This legislation, it says, must haveclarity on the financial commitments, of which the bulk should be provided by theCentral government. Educationists are unequivocal in asserting that resource allocationon education has not been up to the mark even during the UPA government, which hascommitted itself to making right to education a reality. According to the economist andsocial scientist Jayati Ghosh, the entire emphasis of the government has been onenrolment, which no doubt has shown impressive results (the UNESCO reportcorroborates this), but the survival rate and the quality of education, too, are importantand the government has not paid enough attention to these aspects. “Accessibility toschool, especially to schools providing quality education, remains a major concern,” shesays.One reason for the poor quality of education in government schools, she says, isextremely inadequate resources. <strong>India</strong> spends barely 4.1 per cent of its gross domesticproduct (GDP) on education, especially school education, which is extremely inadequate.Quality of education is directly linked to the resources available and the government hasto improve resource allocation to bring about qualitative changes in the field ofeducation.An<strong>other</strong> matter of concern for educationists is that adult literacy programmes have fallenoff the government’s priority list. <strong>The</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>Commission</strong> is in the processof finalising its recommendations on this as well. Based on a round of regional andnational conferences, it has concluded that “illiteracy remains a major problem andtherefore literacy programmes cannot be ignored or given less importance. Expenditureon the <strong>National</strong> Literacy Mission (NLM) must be expanded rather than reduced and givena different focus.” This note emphasises the importance of involving budgetaryprovisions instead of the NLM’s present format of “dependence on underpaid volunteerforce”. According to this note, “better remuneration to literacy workers” will help the