Parasitic morphology in Germanic - Susi Wurmbrand - University of ...

Parasitic morphology in Germanic - Susi Wurmbrand - University of ...

Parasitic morphology in Germanic - Susi Wurmbrand - University of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

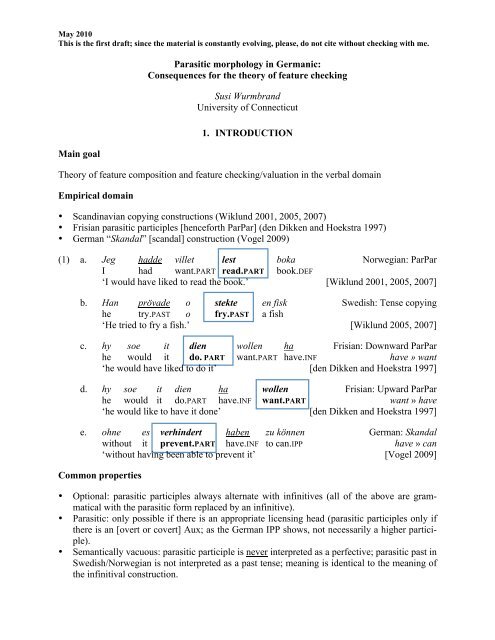

May 2010This is the first draft; s<strong>in</strong>ce the material is constantly evolv<strong>in</strong>g, please, do not cite without check<strong>in</strong>g with me.Ma<strong>in</strong> goal<strong>Parasitic</strong> <strong>morphology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Germanic</strong>:Consequences for the theory <strong>of</strong> feature check<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Susi</strong> <strong>Wurmbrand</strong><strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Connecticut1. INTRODUCTIONTheory <strong>of</strong> feature composition and feature check<strong>in</strong>g/valuation <strong>in</strong> the verbal doma<strong>in</strong>Empirical doma<strong>in</strong>• Scand<strong>in</strong>avian copy<strong>in</strong>g constructions (Wiklund 2001, 2005, 2007)• Frisian parasitic participles [henceforth ParPar] (den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997)• German “Skandal” [scandal] construction (Vogel 2009)(1) a. Jeg hadde villet lest boka Norwegian: ParParI had want.PART read.PART book.DEF‘I would have liked to read the book.’ [Wiklund 2001, 2005, 2007]b. Han prövade o stekte en fisk Swedish: Tense copy<strong>in</strong>ghe try.PAST o fry.PAST a fish‘He tried to fry a fish.’ [Wiklund 2005, 2007]c. hy soe it dien wollen ha Frisian: Downward ParParhe would it do. PART want.PART have.INF have » want‘he would have liked to do it’ [den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997]d. hy soe it dien ha wollen Frisian: Upward ParParhe would it do.PART have.INF want.PART want » have‘he would like to have it done’ [den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997]e. ohne es verh<strong>in</strong>dert haben zu können German: Skandalwithout it prevent.PART have.INF to can.IPP have » can‘without hav<strong>in</strong>g been able to prevent it’ [Vogel 2009]Common properties• Optional: parasitic participles always alternate with <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives (all <strong>of</strong> the above are grammaticalwith the parasitic form replaced by an <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive).• <strong>Parasitic</strong>: only possible if there is an appropriate licens<strong>in</strong>g head (parasitic participles only ifthere is an [overt or covert] Aux; as the German IPP shows, not necessarily a higher participle).• Semantically vacuous: parasitic participle is never <strong>in</strong>terpreted as a perfective; parasitic past <strong>in</strong>Swedish/Norwegian is not <strong>in</strong>terpreted as a past tense; mean<strong>in</strong>g is identical to the mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival construction.

Previous approaches• S<strong>in</strong>ce there are significant differences among the languages when and where parasitic formsare possible, most previous accounts do not aim at a unified analysis for all <strong>of</strong> the above.• Ma<strong>in</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> this talk:o Unified theory that derives parasitic participles <strong>in</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the above constructions (tensecopy<strong>in</strong>g will be left aside here; I only <strong>of</strong>fer some speculations at the end).o Show how <strong>in</strong>dependent language-specific differences derive the differences amongthese constructions across <strong>Germanic</strong>.• Side issues to be covered: IPP and verb cluster reorder<strong>in</strong>g — what, where, where, why?Some conclusions to be reached• “Reverse Agree”: valued probe » unvalued goal• Verb cluster reorder<strong>in</strong>g: can occur <strong>in</strong> syntax or PF (l<strong>in</strong>earization)Previous approaches2. SOME INITIAL OBSERVATIONS• <strong>Parasitic</strong> forms are licensed by higher (c-command<strong>in</strong>g) elemento den Dikken and Hoekstra (1997) (Frisian): Early M<strong>in</strong>imalist check<strong>in</strong>g approach; oneAux checks features on one or more participles (<strong>in</strong> a local configuration); the ‘needy’element is the participle; movement <strong>of</strong> the participle necessary to br<strong>in</strong>g it <strong>in</strong> thecheck<strong>in</strong>g doma<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Aux. This works well for Frisian (cf. the obligatory 3-2-1 order),but cannot, as the authors note, be extended to Swedish/Norwegian.o Wiklund (2005, 2007) (Swedish/Norwegian): copy<strong>in</strong>g relation is “top-down, syntactic,local”; Inverse Agree approach, where parasitic forms are transmitted top-down;notes <strong>in</strong>consistency with the standard probe – goal approach, which situates the deficit<strong>in</strong> the higher probe.(2) Probe – goal system (Chomsky 2001)uF [__] » iF: valuedall uF need to undergo Agree (to delete)Aux » Part1 » Part2uT: [__] iT: perf iT: perfProblems:Notation (rest <strong>of</strong> the talk):iF <strong>in</strong>terpretable featureuF un<strong>in</strong>terpretable featurei/uF: [__] unvalued featurei/uF: x valued feature (feature value x)i/uF: [x] unvalued feature that has beenvalued with value xo Wrong semantics (second participle is not <strong>in</strong>terpreted as a participle)o How can the dependency <strong>of</strong> Part2 on higher Aux/Part1 be guaranteed? How is multipleAgree ever possible?2

Basic proposal• Relation needs to be top-down (the ‘needy’ element is the lower element): “Reverse” Agree• ParPar (Swedish/Norwegian, Frisian): multiple Agree between a licens<strong>in</strong>g Aux and dependentparticiples• Verbs need to value features via Agree with a c-command<strong>in</strong>g head conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the appropriatevalued features.(3) Aux (β) » Part (α) » Part (α)iT: perf uT: [__] uT: [__] multiple Agree/valuation(4) AgreeA feature F: [__] on a head α is valued by a feature F: x on β, iffi. β c-commands αii. α is accessible to β [roughly with<strong>in</strong> the same phase—see below]iii. There is no γ with a valued <strong>in</strong>terpretable feature F such that γ commands α and is c-commanded by β.• This version <strong>of</strong> Agree is similar to the Agree version proposed <strong>in</strong> Zeijlstra (2010) who alsoargues that the c-command<strong>in</strong>g element <strong>in</strong> an Agree relation carries the <strong>in</strong>terpretable (herevalued) feature, whereas the c-commanded element carries the un<strong>in</strong>terpretable (here unvalued)feature. The evidence presented by Zeijlstra, among others, <strong>in</strong>cludes multiple nom<strong>in</strong>ativelicens<strong>in</strong>g, negative concord, and sequence <strong>of</strong> tense. The analysis presented here willstraightforwardly carry over to these phenomena as well.• My approach differs from Zeijlstra’s <strong>in</strong> def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Agree as be<strong>in</strong>g driven by valuation ratherthan (un)<strong>in</strong>terpretable features. In the course <strong>of</strong> this talk, I will present further evidence (seePesetsky and Torrego 2007, Bošković To appear) for separat<strong>in</strong>g the notion <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretability(iF/uF) from the notion <strong>of</strong> valuation and for Agree be<strong>in</strong>g valuation-driven.The bigger picture• The analysis here is <strong>in</strong> a sense a return to check<strong>in</strong>g theories (s<strong>in</strong>ce the ‘<strong>in</strong>adequacy’ [unchecked/unvaluedfeatures] is placed <strong>in</strong> the lower element) and a departure from standardprobe – goal systems (<strong>in</strong>adequacy lies <strong>in</strong> the probe).• The analysis is different from earlier analyses (den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997, Bošković1995, 1999), however, <strong>in</strong> that the <strong>in</strong>adequacy can be elim<strong>in</strong>ated via Agree and no movementis necessary. This is crucial for a unified analysis <strong>of</strong> the constructions <strong>in</strong> (1), as Swedish/Norwegianparasitism cannot be derived by movement.• Standard Agree vs. “reverse” Agree: Ma<strong>in</strong> issue/difference — location <strong>of</strong> the valued features(5) Pesetsky & Torrego: T: iT: [__] » V: uT: pastp. 11: “[…] reason for assum<strong>in</strong>g that the T-feature <strong>of</strong> Tns is unvalued, though <strong>in</strong>terpretable:the fact that Tns appears to learn its value <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ite clauses from the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb.”3

• Why T from the verb and not the verb from T?• <strong>Parasitic</strong> constructions (multiple Agree) may show that this is not a chicken-egg problem: theverb does appear to be dependent on the higher element, rather than vice versa.• Same po<strong>in</strong>t can be made about the <strong>Germanic</strong> Inf<strong>in</strong>itivus pro participio (IPP) construction.Modals <strong>in</strong> Aux – Mod – V constructions do not (or only marg<strong>in</strong>ally <strong>in</strong> German; see Baderand Schmid 2009) occur <strong>in</strong> the participle form; <strong>in</strong>stead, the IPP is used.(6) a. dat Jan het boek heeft kunnen lezen Dutchthat Jan the book has can.IPP read.INF‘that Jan has been able to read the book’b. dass Jan das Buch hat lesen können Germanthat Jan the book has read.INF can.IPP‘that Jan has been able to read the book’• If Aux had to be licensed by a verb valued as a participle, it is not clear how an Aux <strong>in</strong> anIPP construction could be valued. Rather, the IPP, which is <strong>in</strong>terpreted as a participle, seemsto be dependent on the auxiliary (see also den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997 for this po<strong>in</strong>t).• Standard probe – goal system: could cover some <strong>of</strong> the ParPar constructions, but the ma<strong>in</strong>advantage <strong>of</strong> the current approach is its explicitness and the fact that a unified account <strong>of</strong> allthe parasitic constructions is possible, with most restrictions be<strong>in</strong>g derived from <strong>in</strong>dependentproperties <strong>of</strong> the languages.3.1 Verbal features & clause structure3. THE SYSTEM• All <strong>in</strong>terpretable verbal heads have an iT; typically (but not necessarily, see section 5), the iTcomes valued (I consider all tense, mood, and aspect features as <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g an iT, thoughsome dist<strong>in</strong>ctions are necessary for Case assignment):T Aux/Mod English lexical items NotesiT: past iT: perf(ective) haveiT: ∅iT: pres iT: prog(ressive) beiT: ∅ iT: imp(erfective) ∅iT: pass(ive) beiT: mod(al), irr(ealis) can, may, must, woll…zero tense <strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives(see <strong>Wurmbrand</strong> 2007, 2008)iT: mod cover feature for different (semantic)types <strong>of</strong> modals (epistemic,circumstantial, etc.)• All verbal heads have an uT, typically (but not necessarily, aga<strong>in</strong> section 5) unvalued.• Agree <strong>in</strong> (4): uTs: [__] are valued by the closest i/uF: val (with<strong>in</strong> the right doma<strong>in</strong>).• Standard assumption about uTs: not <strong>in</strong>terpretable <strong>in</strong> semantics; must be deleted before LF.• PF: I assume that the uT value is what is realized at PF (alternative to affix hopp<strong>in</strong>g).uT English lexical items uT English lexical itemsuT: past -eduT: perf participleuT: pres ∅uT: prog -<strong>in</strong>guT: ∅ <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itiveuT: pass participleuT: mod/irr <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive4

(7) a. He must have been left alone.b. TP [For this talk, I ignore whether T also <strong>in</strong>volves a uT; this3 will depend on one’s assumptions about the properties <strong>of</strong> C.]T AuxPiT: mod 3Aux AuxPiT: perf 3uT: [__] AuxP VPiT: pass @uT: [__] VuT: [__]c. TP3T AuxP iT: mod can, must, …iT: mod 3 iT: perf; uT: [mod] have + INFAux AuxP iT: pass; uT: [perf] be + PARTiT: perf 3 uT: [pass] V + PARTuT: [mod] AuxP VPiT: passuT: [perf]@VuT: [pass]Important assumption that will be relevant later: Valuation can occur at any po<strong>in</strong>t dur<strong>in</strong>g thederivation (as long as the elements <strong>in</strong>volved appear <strong>in</strong> the right configuration and doma<strong>in</strong>).3.2 Clause structure and doma<strong>in</strong>s(8) Accessibility [Former PIC]i. α is accessible to β iff α is not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> a Spell-Out doma<strong>in</strong> at the time <strong>of</strong> valuation.ii. Spell-Out doma<strong>in</strong>: complete phase m<strong>in</strong>us the Edge (Edge = head, specifier)Doma<strong>in</strong>s, phases• vP, CP (maybe DP, PP…)• One modification: only ϕ-complete vPs count as complete phases (only ϕ-complete v countsas a phase head); vPs that <strong>in</strong>volve unvalued ϕ-features are ϕ-<strong>in</strong>complete and not complete.• Once all unvalued ϕ-features are valued, the phase is complete and subject to Spell-Out.Clause structure• Functional structure: TP » Aux/AspP* » vP » Aux/AspP » VP• English modals: only <strong>in</strong> T (*He has must…, *He must can…)• Modals <strong>in</strong> other <strong>Germanic</strong> languages:o Merged as ma<strong>in</strong> verbs (V):o Functional heads (Mod/Aux):uT: [__]; select subject (i.e., control)iT: mod; uT: [__]; no subject (i.e., rais<strong>in</strong>g)5

phaseSpell-Out doma<strong>in</strong>4. PARASITIC PARTICIPLES4.1 <strong>Parasitic</strong> participles <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian(9) a. Jeg hadde villet lese boka Inf<strong>in</strong>itiveI had want.PART read.INF book.DEF‘I would have liked to read the book.’b. TP Rais<strong>in</strong>g3T AuxP[AgrS and Case valuation is ignoredhere.]iT: past 3AuxModPiT: perf 3uT: [past] Mod vPhad.PAST iT: mod 3uT: [perf] Spec v’want.PART DP 3v VP2 @V v t VuT: [mod]read.INFc. TP Control3T AuxPiT: past 3AuxvPiT: perf 3uT: [past] DP v’3v+V VPuT: [perf] 3want.PART V AspP (InfP)t V 3Asp vPiT: irr 3PRO v’• Once subject is merged,vP is complete and sent toSpell-Out.• Spell-Out doma<strong>in</strong>: VP• Vv to escape Spell-Out• uT <strong>of</strong> V (and possibly v)valued by Mod (Edge isaccessible to elements <strong>in</strong>higher phase).• Inf<strong>in</strong>itive <strong>in</strong>cludes anAsp/Mod head (Wiklund2001, 2005, 2007; or InfPà la Kayne 1989, 1991)with an iT: irr.• No TP <strong>in</strong> modal <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives(see <strong>Wurmbrand</strong> 2007,2008 for arguments fordist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g tense andMod/Asp [woll]).3v+V VPuT: [irr] @read.INFGiven the ongo<strong>in</strong>g controversy about whether modal constructions <strong>in</strong>volve control and/or rais<strong>in</strong>g, I assumehere that both structures are <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple available (see <strong>Wurmbrand</strong> 1999 for arguments that at leastnon-dynamic modal constructions can <strong>in</strong>volve rais<strong>in</strong>g). I do, however, assume that for modals, the rais<strong>in</strong>gvs. control dist<strong>in</strong>ction correlates with the functional vs. lexical status <strong>of</strong> the verb. In what follows, I willonly give one successful derivation for all grammatical examples, as this is all that is needed to accountfor well-formedness. To exclude ungrammatical examples, the failure <strong>of</strong> both options will be illustrated.t V6

<strong>Parasitic</strong> participles• Related to restructur<strong>in</strong>g (Wiklund 2001, 2005, 2007)• Here: Lack <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival iT: irr (irrealis/future mean<strong>in</strong>g comes directly from modal)• Matrix Aux <strong>in</strong> lower position (<strong>in</strong> or below v).(10) a. Jeg hadde villet lest boka ParParI had want.PART read.PART book.DEF‘I would have liked to read the book.’ [Wiklund 2001, 2005, 2007]b. TP3TvPiT: past 3DP v’3v+Aux AuxPiT: perf 3uT: [past] Aux• Mod = V (no iT), cannot value lower uTs.• Aux <strong>in</strong>/below v values the lower uTs.• DP values ϕ-features <strong>of</strong> PRO (see below);matrix vP subject to Spell-Out.• T values matrix v+Aux (accessible s<strong>in</strong>ce atthe Edge).VPt Aux 3VvPuT: [perf] 3want.PART PRO v’3v+V VPuT: [perf] @read.PARTt VPrediction: If licens<strong>in</strong>g head is above vP, feature shar<strong>in</strong>g/copy<strong>in</strong>g impossible 1• Modal constructions do not allow tense shar<strong>in</strong>g/copy<strong>in</strong>g (tense shar<strong>in</strong>g is possible <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong>constructions <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian, but they <strong>in</strong>volve a very different structure; see section6).(11) a. *Han kunde lästeHe can.PAST read.PAST OK read.INF‘He could read’ [Wiklund 2005, 2007]b. *Hon sa att han <strong>in</strong>te kunde lästeShe said that he not can.PAST read.PAST OK read.INF‘She said that he could not read.’[A.-L. Wiklund, p.c.]1 This account also predicts that parasitic participles are only possible <strong>in</strong> the control structure (the rais<strong>in</strong>g structurewould <strong>in</strong>volve a functional modal with an iT: mod, which would block valuation <strong>of</strong> the embedded V by Aux). I wasnot able to verify yet whether this prediction is correct.7

c. * TP3(Im)possible derivations:T vP• Functional Mod: iT, hence <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itiveiT: past 3obligatory; no parasitic formsDP v’• Lexical Mod: Agree between T and embeddedv impossible; after the subject is3v+V VPmerged, the matrix VP is sent to SpelluT:[past] 3 Out; embedded v+V is then not accessibleanymore.can.PAST V vP3PRO v’3Spell-Out doma<strong>in</strong>vuT: [__]VP@VuT: [__]• Side conclusion: no V/v-movement <strong>in</strong> restructur<strong>in</strong>g (if embedded V could move to matrix v,it should be possible to get valued by T).Further Evidence: Recursive ParPars(12) Han hade velat kunnat simmat Recursive ParParhe had want.PART can.PART swim.PART‘He would have liked to be able to swim.’ [Wiklund 2001]• Recursive parasitic participles: Evidence for PRO postpon<strong>in</strong>g phase-hood and Spell-Out.• Consider the stage before the highest subject is merged <strong>in</strong> (13):o v Aux can ‘see’ v2 (plus V2, given Vv), s<strong>in</strong>ce Spell-Out <strong>of</strong> VP1 has not occurred yet.o But if PRO vPs were full phases, v3+V3 would be <strong>in</strong>accessible to v1, s<strong>in</strong>ce VP2would have been sent to Spell-Out.o Valuation <strong>of</strong> v3+V3 by Aux would be impossible; recursive ParPars should be *.o Assumption that PRO-vPs are not complete phases: Agree all the way down is possible,and multiple ParPars are correctly predicted to be possible.• OC-PRO: unvalued (but <strong>in</strong>terpretable) ϕ-features which get valued by the controller. v comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gwith PRO is ϕ-<strong>in</strong>complete until PRO is valued.• vP3, vP2 are not ϕ-complete, hence by the def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> Accessibility not subject to Spell-Out.• Once the matrix DP is merged, the ϕ-features <strong>of</strong> PRO get valued, and the embedded VPs becomeSpell-Out doma<strong>in</strong>s. 22 To determ<strong>in</strong>e when exactly the lower vPs become phases, it will be relevant to look at object control. Wiklundstates that ParPars are possible with låta ‘let, allow’, which, accord<strong>in</strong>g to her, can <strong>in</strong>volve object control. If objectcontrol is possible <strong>in</strong> ParPar constructions, valuation <strong>of</strong> PRO cannot occur as soon as the controller is merged, but itmust be possible to postpone PRO valuation until Aux is merged. S<strong>in</strong>ce this would be with<strong>in</strong> one phase and valuation,by assumption, can occur at any stage <strong>of</strong> the derivation, this should not be a problem. However, more data areneeded to verify these suggestions.8

• S<strong>in</strong>ce Aux can be merged lower than (i.e., before) the subject, it can value all embedded uTsbefore the vPs become complete phases.[To simplify the structure, I place Aux directly <strong>in</strong> v. Noth<strong>in</strong>g would change if it is <strong>in</strong> a lowerAsp/Aux and moves to v.](13) TP3T vP1iT: past 3DP v’ Not a Spell-Out Doma<strong>in</strong>3v AuxVP1iT: perf 3have V1 vP2uT: [perf] 3want.PART PRO v’3v2+V2 VP2uT: [perf] 3can.PART V2 vP3t V 3PRO v’3v3(+V3) VP3uT: [perf] @swim.PART4.2 Downward parasitic participles <strong>in</strong> Frisian• My claim (contrary to previous analyses): the downward ParPar construction <strong>in</strong> Frisian isderived <strong>in</strong> exactly the same way as the ParPar construction <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian.Possible ParPars <strong>in</strong> Frisian(14) a. hy soe it dien wollen ha Aux INF f<strong>in</strong>alhe would it do. PART want.PART have.INF‘he would have liked to do it’ [den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997: 1058, ex. (3b)]b. omdat hy it dien wollen ha soe Aux INF f<strong>in</strong>albecause he it do. PART want.PART have.INF would‘because he would have liked to do it’[E. Hoekstra, p.c.]c. sûnder dat echt dien wold te hawwen 3 Aux INF f<strong>in</strong>alwithout that really do.PART want.PART to have.INF‘without really hav<strong>in</strong>g wanted to do it’[E. Hoekstra, p.c.]t V3 The <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival form hawwen is shortened to ha <strong>in</strong> spoken Frisian, which is reflected <strong>in</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the data. Thechoice has no bear<strong>in</strong>g on the data.9

d. ?dat er dat dien k<strong>in</strong>nen hie Aux FIN f<strong>in</strong>althat he that do.PART can.PART had‘that he had been able to do it’[J. Hoekstra, p.c.]• Thanks to E. Hoekstra for provid<strong>in</strong>g me with the follow<strong>in</strong>g examples with f<strong>in</strong>ite f<strong>in</strong>al Aux(found via an <strong>in</strong>ternet search).(15) a. Mar benammen wol ik Mattie en ús bêrn Bauke, Jelte-Pieter en T<strong>in</strong>eke tank sizze foaral de op<strong>of</strong>ferjens…But I especially want to say thanks to Mattie and our children Bauke, Jelte-Pieter andT<strong>in</strong>eke for all the sacrifices…dy’t sy de ôfroune jierren dien moatten ha […]which they the past years do.PART must.PART have‘which they had to make <strong>in</strong> the past years…’b. Ik t<strong>in</strong>k dat immen earst fuot west moatten hat […om]I th<strong>in</strong>k that someone first away be.PART must.PART has [<strong>in</strong> order to]‘I th<strong>in</strong>k that someone had to first be away [<strong>in</strong> order to…]’c. Ik b<strong>in</strong> tankber dat ik sa folle dien k<strong>in</strong>nen haw […]I am thankful that I so much do.PART can.PART have‘I’m grateful that I was able to do so much…’• All <strong>of</strong> the above: participles alternate with <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives (Mod = functional or emb. iT: irr)• ParPars: as <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian, Mod can be a ma<strong>in</strong> verb which embeds a PRO-vP complement.• There are two differences between the two languages, but I will argue that these follow from<strong>in</strong>dependent properties <strong>of</strong> the languages.Word ordero Word order: Frisian 3-2-1; Swedish/Norwegian 1-2-3o One context that is impossible <strong>in</strong> Frisian: *when the licens<strong>in</strong>g Aux is <strong>in</strong> C.• S<strong>in</strong>ce ParPars are licensed top-down (see the structure <strong>in</strong> (10)), movement is not required toderive a ParPar (contra den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997, Bošković 1995, 1999).• Frisian & Swedish/Norwegian hence can <strong>in</strong>volve the same syntax (the same hierarchical relations/sameAgree relations between Aux & participles).• Word order: head-f<strong>in</strong>al structure for Frisian, which I assume can be an effect <strong>of</strong> languagespecific PF-l<strong>in</strong>earization rules for heads & complements.o Syntax: Frisian = Swedish/Norwegian (structure <strong>in</strong> (10))o PF: Swedish/Norwegian l<strong>in</strong>earizes the head before the complement; Frisian l<strong>in</strong>earizesthe complement before the head (i.e., ModP before Aux; VP before Mod etc.)10

Further support• Recursive ParPars are also possible <strong>in</strong> Frisian; as long as there is no <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive <strong>in</strong> between theparticiples (examples from den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997: 1068; exx (24)).(16) All: ‘He would have liked to be able to do it’a. hy soe it dwaan k<strong>in</strong>ne wollen hahe would it do.INF can.INF want.PART have.INFb. hy soe it dwaan k<strong>in</strong>nen wollen hahe would it do.INF can.PART want.PART have.INFc. hy soe it dien k<strong>in</strong>nen wollen hahe would it do.PART can.PART want.PART have.INFd. ??hy soe it dien k<strong>in</strong>ne wollen hahe would it do.PART can.INF want.PART have.INF• This follow from the current analysis (verbs <strong>in</strong> their hierarchical order):(17) a. Aux Mod1.PART Mod2.INF V3.INF Mod1 & Mod2: functionalb. Aux Mod1.PART Mod2.PART V3.INF Mod1: lexical; Mod2: functionalc. Aux Mod1.PART Mod2.PART V3.PART Mod1 & Mod2: lexicald. ??Aux Mod1.PART Mod2.INF V3.PART cannot be derived• To get an <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive on Mod2, Mod1 has to either be functional (with iT: mod) or embed an<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival Asp with iT: irr.• Independently <strong>of</strong> the location <strong>of</strong> Mod2, valuation <strong>of</strong> V3 by Aux across the iT <strong>of</strong> Mod1 or<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival Asp will be impossible; whatever head values Mod2 as an <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive will be closerto V3 than Aux.Restriction: *Aux <strong>in</strong> C• V2 <strong>of</strong> Aux impossible (V2 <strong>of</strong> higher Mod is f<strong>in</strong>e)(18) a. *hy hat it dien wollen *Aux <strong>in</strong> Che has it do. PART want.PART OK if do.INF‘he has wanted to do it’ [den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997: 1082]b. *Hy hie dat dien k<strong>in</strong>nen *Aux <strong>in</strong> CHe had that do. PART can.PART OK if do.INF‘He had been able to do it.’[J. Hoekstra, p.c.]• Crucial part <strong>of</strong> the derivation <strong>of</strong> ParPar is that the licens<strong>in</strong>g Aux is <strong>in</strong>/below v (otherwise itwould be too high to access heads <strong>in</strong> the VP).• This was possible s<strong>in</strong>ce, per assumptions, Aux can freely be <strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong> either the higher orthe lower AuxP/AspP. Insertion <strong>of</strong> Aux <strong>in</strong> the lower AuxP/AspP must also be possible <strong>in</strong> Frisian,s<strong>in</strong>ce ParPars are possible <strong>in</strong> (14), (15), and (16).11

• Assumption: Insertion <strong>of</strong> Aux is only free <strong>in</strong> Frisian when Aux does not move to C (<strong>in</strong> all <strong>of</strong>(14) through (16), Aux can be <strong>in</strong>serted low, and ParPars are possible). When Aux moves toC, as <strong>in</strong> (18), it must be <strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong> the higher position, hence ParPars are excluded.• Why should this be the case? Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary suggestion: some form <strong>of</strong> shortest move; if Aux is<strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong> the higher Aux position, movement to C would be shorter. If there is no movement<strong>of</strong> Aux to C, it doesn’t matter where Aux is <strong>in</strong>serted.• Obvious question: Why is only Frisian subject to such an economy consideration (Swedish/Norwegianare also V2 languages)? Possible direction (J. Bobaljik, p.c.): perhaps V2is/can be different <strong>in</strong> the two languages; Frisian must <strong>in</strong>volve movement <strong>of</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>ite V to C(due to the head-f<strong>in</strong>al l<strong>in</strong>earization, which otherwise always puts the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb at the end); <strong>in</strong>a head-<strong>in</strong>itial language, V2 could be met by the f<strong>in</strong>ite verb <strong>in</strong> situ (as long as it is PF-second).4.3 Upward parasitic participles <strong>in</strong> Frisian• One context where Frisian is radically different from Swedish/Norwegian: “upward” ParPars((19)a).• Given the top-down Agree approach, the existence <strong>of</strong> upward parasitism might appear surpris<strong>in</strong>g.How can a feature be licensed upwards?• There is one restriction on this construction, which is not <strong>in</strong> effect <strong>in</strong> the downward ParPar((19)c): upward ParPars are only possible when the higher Mod is <strong>in</strong> C (cf. (19)a vs. (19)b).(19) a. hy soe it dien ha wollen Upward ParParhe would it do.PART have.INF want.PART want » have‘he would like to have it done’ [den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997]b. *omdat hy it dien ha k<strong>in</strong>nen soe *Mod f<strong>in</strong>albecause he it do.PART have.INF can.PART would OK if Mod.INF‘because he would be able to have done it’c. omdat hy it dien wollen ha soe Downward ParParbecause he it do. PART want.PART have.INF would‘because he would have liked to do it’[E. Hoekstra, p.c.](20)a. * CP2C TPbecause 2T ModPwould 2Mod AuxPcan.PART 2Auxhave.INFvP@Vdo.PARTb. CP2C TPwould 2T ModPt T 2Mod AuxPcan.PART 2Auxhave.INFvP@Vdo.PART12

Ma<strong>in</strong> claim:There is no “upward” licens<strong>in</strong>g; rather, the c-command relation between the Aux& participle is reversed due to movement. “Upward” ParPar: regular Agree.Word order aga<strong>in</strong>• Claim: descend<strong>in</strong>g word orders (e.g., 3-2-1) can be the result <strong>of</strong> PF-l<strong>in</strong>earization or syntacticmovement. By just look<strong>in</strong>g at a 3-2-1 word order, we can’t know whether movement has appliedor not; certa<strong>in</strong>ly, the postulation <strong>of</strong> movement would not be implausible.• Above, we have seen that movement is not necessary to derive ParPars <strong>in</strong> the 3-2-1 order, butthis does not mean that movement is not possible.• Ways to motivate the existence <strong>of</strong> syntactic movement (as opposed to simple l<strong>in</strong>earization):o Semantic effect: No (none <strong>in</strong> verb clusters)o New syntactic relations: Yes—ParPar (movement creates new Agree relations, whichare reflected <strong>in</strong> the morphological form verbs can take)o Locality restrictions: Yes (I argue that the *Aux <strong>in</strong> C restriction follows from the locality<strong>of</strong> Agree; importantly, this restriction only arises when a ParPar is used—i.e.,when a new syntactic Agree relation is to be established)• Claim: AuxP moves to Spec,Mod1(21) CP3CTP{would+T} 3T ModP14AuxP iT: perf ModP1’@ 3… have.INF … Mod1 ModP2{would} 3iT: mod Mod2 t AuxPuT.[perf]• Mod2 can be valued by Mod1 (recall that valuation can occur at any stage) <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive• Mod2 can also be valued by AuxP (assum<strong>in</strong>g the features <strong>of</strong> the head are also part <strong>of</strong> theXP), however, this will only be possible if Mod1 gets out <strong>of</strong> the way first.• Note: Agree <strong>in</strong> (4) crucially does not require that the element with a valued F (β) is a head.• If Mod1 C: AuxP <strong>in</strong> Spec,ModP1 is the closest element with a valued T-feature to Mod2,and hence AuxP can value Mod2 (after Mod1 has moved to C).• If Mod1 stays <strong>in</strong> situ ((19)b): AuxP cannot value Mod2, and a ParPar is excluded. 44 An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g question is whether all reorder<strong>in</strong>g is done by movement <strong>in</strong> cases where we have evidence for somesyntactic movement, or whether a mix <strong>of</strong> movement and PF-l<strong>in</strong>earization is also possible. For <strong>in</strong>stance, does the dovP<strong>in</strong> (21) also move to a position above AuxP (e.g., top specifier <strong>of</strong> [or adjo<strong>in</strong>ed to] ModP1), or is the word orderV»Aux the result <strong>of</strong> head-f<strong>in</strong>al l<strong>in</strong>earization? At this po<strong>in</strong>t, I do not have enough evidence to decide on this po<strong>in</strong>t.13

Important derivation to exclude:• Movement <strong>of</strong> AuxP to Spec,ModP2 must be impossible (Mod1 would then not be <strong>in</strong> betweenAuxP & Mod2, and the position <strong>of</strong> Mod1 would not matter—(19)b not accounted for)• Two ways to exclude that derivation:o Antilocality (Abels 2003)/Last Resort (Bobaljik 1995)—movement <strong>of</strong> complement tospecifier position <strong>of</strong> same head is “too short”. This would entail that valuation undersisterhood should be possible, which raises a number <strong>of</strong> technical issues, complicat<strong>in</strong>gthe analysis. S<strong>in</strong>ce it also does not seem to extend to the control structure <strong>of</strong> modalconstructions, I will prelim<strong>in</strong>arily pursue the second option for Frisian here.o No movement to the middle <strong>of</strong> a verb cluster <strong>in</strong> Frisian. The current analysis (like allother syntactic accounts <strong>of</strong> verb cluster reorder<strong>in</strong>g) does not solve the question <strong>of</strong>why certa<strong>in</strong> reorder<strong>in</strong>gs take place <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> languages and constructions or whattriggers movement. Fact is that verb clusters show certa<strong>in</strong> reshuffl<strong>in</strong>gs, which I claimhere can be the result <strong>of</strong> syntactic movement. S<strong>in</strong>ce Frisian only allows strictly descend<strong>in</strong>gword orders (3-2-1) and orders such as 1-3-2 do not exist, a natural assumptionis that movement always targets the top <strong>of</strong> the verb cluster. Movement <strong>of</strong> AuxPbetween Mod1 and Mod2 is thus excluded. This assumption also correctly excludesmovement <strong>of</strong> AuxP between the two modals <strong>in</strong> a control (i.e., ma<strong>in</strong> verb) structure.o Furthermore, this assumption accounts for why movement cannot apply to generatethe structure <strong>in</strong> (16)d: a potential derivation to yield this configuration would be tomove vP (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g V3) above Mod1 but below Aux; <strong>in</strong> this position, V3 could thenbe valued by Aux, despite Mod2 be<strong>in</strong>g valued as an <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive. However, s<strong>in</strong>cemovement <strong>of</strong> vP does not target the top <strong>of</strong> the verb cluster, it is excluded.Recursive upward ParPar• The movement analysis correctly predicts recursive upward ParPars. The structure is exactlylike the recursive ParPar structure <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian, with the difference that AuxP getsto the position from where it can value the lower verbs by movement <strong>in</strong> Frisian (i.e., semanticallyAuxP is lower), and that the verbs are l<strong>in</strong>earized <strong>in</strong> head-f<strong>in</strong>al order.• S<strong>in</strong>ce the embedded vPs <strong>in</strong>volve PRO, they are not complete phrases, and movement canproceed unrestricted (see below for more details on movement).(22) hy soe it dien ha k<strong>in</strong>nen wollenhe would it do.PART have.INF can.PART want.PART‘He would like to be able to have done it.’ [den Dikken and Hoekstra 1997]14

(23) vP3DP v’3vSome predictions <strong>of</strong> this accountVP13AuxP iT: perf VP1@ 3Aux… V V1 vP2t V 3would PRO v’3v2VP23V2 vP3uT: [perf] 3want.PART PRO v’3v3 VP33V3uT: [perf]can.PART• The restriction that the higher Mod must be <strong>in</strong> C should not (and does not) arise <strong>in</strong> the Frisiandownward ParPar construction. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> this construction no movement is necessary (Auxstarts out higher than the verbs that are valued as participles), the position <strong>of</strong> elements aboveAux is irrelevant.• Upward parasitism is not possible <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian — strict 1-2-3 orders, hence nomovement, hence no upward parasitic construction.4.4 Summariz<strong>in</strong>g…Sw Fr Reason/ConsequenceWord order1-2-3 3-2-1 Movement <strong>in</strong> Fr possibleUpward ParPar No Yes Mov’t <strong>of</strong> AuxP above higher Mod requiredDownward ParPar Yes Yes Mod = V; Aux <strong>in</strong>/below vRecursive ParPar Yes Yes PRO postpones Spell-OutAux <strong>in</strong> C (downward) Yes No Perhaps difference <strong>in</strong> V2 due to headedness*Mod above Aux not <strong>in</strong> C N/A Yes Only <strong>in</strong> upward ParPar; Mod needs to get out <strong>of</strong> the wayt AuxP4.5 Other languages?• Construction <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g ParPar: Aux – Mod – V• English: modals are <strong>in</strong> T; cannot be embedded under Aux; Aux – Mod – V cannot be generated<strong>in</strong> any form (as for tense copy<strong>in</strong>g see below).15

What about German?• Ge Skandal construction: similar to the ParPar <strong>in</strong> (14)c (difference: IPP and word order) 5• But: the analogues <strong>of</strong> (14)b,d, (15), as well as upward ParPar constructions are impossible.(24) a. ohne es verh<strong>in</strong>dert haben zu können German: Skandalwithout it prevent.PART have.INF to can.IPP have » can‘without hav<strong>in</strong>g been able to prevent it’ [Vogel 2009]Questionsb. *weil er es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dert hat können *ParPar (3-1-2)s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not prevent.PART has can.IPP OK: prevent.INF‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has not been able to prevent it’c. *weil er es nicht hat verh<strong>in</strong>dert können *ParPar (1-3-2)s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not has prevent.PART can.IPP OK: prevent.INFd. *Er würde es getan haben gewollt *Upward ParParHe would it do.PART have.INF want.PART OK: want.INF‘he would like to have it done’• What contexts allow parasitic participles <strong>in</strong> German?• What is the difference b/w Swedish/Norwegian/Frisian vs. German?• Why is the Frisian upward ParPar not possible <strong>in</strong> German (given that German verb clustersdo appear <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>verted orders, hence may <strong>in</strong>volve syntactic movement)?Answer can’t be…• Two immediate differences between Fr/Ge: IPP, lack <strong>of</strong> fully descend<strong>in</strong>g order (3-2-1)• Note, however, that, at least marg<strong>in</strong>ally, the participial construction is possible <strong>in</strong> German,when then must appear <strong>in</strong> the 3-2-1 order.• Crucially, ParPar is still blocked <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g (f<strong>in</strong>ite) context.(25) a. dass Jan das Buch lesen gekonnt hat Ge: 3-2-1that Jan the book read.INF can.PART has‘that Jan has been able to read the book’b. *dass Jan das Buch gelesen gekonnt hat *ParParthat Jan the book read.PART can.PART has5 The Skandal construction also has the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival marker zu ‘to’ <strong>in</strong> the ‘wrong’ place (namely, before the modal<strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> the auxiliary, which is structurally the highest element). This is also the case <strong>in</strong> the non-parasitic version<strong>of</strong> (24)a where the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive is used <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> the participle. Hence the placement <strong>of</strong> zu is not a special property <strong>of</strong>the Skandal construction, but <strong>of</strong> German Aux – Mod – V constructions <strong>in</strong> general. The generalization regard<strong>in</strong>g theplacement <strong>of</strong> zu is that it has to appear before the f<strong>in</strong>al verb <strong>of</strong> a verb cluster str<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>dependently <strong>of</strong> what that verbis. I follow Vogel (2009), who argues that placement <strong>of</strong> zu is not determ<strong>in</strong>ed by syntactic position, but rather by a(late) PF-edge constra<strong>in</strong>t.16

5.1 A few facts about the Skandal5. “SKANDAL” CONSTRUCTION• Skandal construction noted <strong>in</strong> Reis (1979), Merkes (1895), Meurers (2000)• First exhaustive exam<strong>in</strong>ation: Vogel (2009) who did a number <strong>of</strong> experimental studies test<strong>in</strong>gthe acceptability <strong>of</strong> this construction.p. 311• Crucial fact: Skandal construction is more frequent than the regular IPP construction• Follow up studies (grammaticality judgment study, <strong>in</strong>ternet search), all with the same result.p. 312• Writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>f this construction as a non-standard, marg<strong>in</strong>al phenomenon, or a repair strategyused to deal with the lack <strong>of</strong> explicit grammatical rules (Reis 1979; see Vogel 2009 for an extensivecriticism <strong>of</strong> this approach) is hence not appropriate.5.2 Generalization: *Skandal construction with complete vPs• Vogel (2009): Skandal construction only <strong>in</strong> non-f<strong>in</strong>ite contexts(26) a. ohne es verh<strong>in</strong>dert haben zu können German: Skandalwithout it prevent.PART have.INF to can.IPP have » can‘without hav<strong>in</strong>g been able to prevent it’ [Vogel 2009]b. *weil er es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dert hat können *Skandal (3-1-2)s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not prevent.PART has can.IPP OK: prevent.INF‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has not been able to prevent it’17

c. *weil er es nicht hat verh<strong>in</strong>dert können * Skandal (1-3-2)s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not has prevent.PART can.IPP OK: prevent.INF• I suggest a different <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> Vogel’s observation: the Skandal construction is impossiblewhen the vP where the participle orig<strong>in</strong>ates is a complete vP—i.e., a vP with a ϕ-complete DP subject.(27) a. * b. OK3Aux 3ModvP3DP 3v 3V.PARTEvidence: causatives & perception verbs3Aux 3ModvP3∅/PRO 3v 3V.PART• As shown <strong>in</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> the corpus study conducted by Vogel, the Skandal constructionalso exists with the causative verb lassen ‘let’.(28) Der Kreml wirft ihm im Gegenzug vorThe Kreml<strong>in</strong> accuses him <strong>in</strong> returnsich die Dienste von Prostituierten von e<strong>in</strong>em BankmanagerSELF the servies <strong>of</strong> prostitutes by a bank.managerbezahlt haben zu lassenpay.PART have.INF to let‘In return, the Kreml<strong>in</strong> accuses him <strong>of</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g let a bank manager pay him for theservices <strong>of</strong> prostitutes.’• The example above <strong>in</strong>volves an embedded passive (cf. the subject a bank manager occurs asa by-phrase, and could, <strong>in</strong> fact, be dropped), which under let occurs with active <strong>morphology</strong>.A simpler example illustrat<strong>in</strong>g this construction is given below:(29) Ich ließ ihn feuernI let him fire‘I let him get fired. I let someone fire him.’• The examples with let are also important <strong>in</strong> that they clearly show that the Skandal construction<strong>in</strong>volves the underly<strong>in</strong>g hierarchical (semantic) order Aux » Mod/let » V, rather thanMod/let » Aux » V: <strong>in</strong> passive let-constructions the auxiliary have is impossible <strong>in</strong> that order(have can only occur above let).(30) a. *weil er sich bezahlt haben ließs<strong>in</strong>ce he SELF pay.PART have.INF let.PAST‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he let have paid him’‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has let pay him’18

. weil er sich bezahlen hat lassens<strong>in</strong>ce he SELF pay.PART have.PRES let.IPP‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has let pay him’• Strik<strong>in</strong>gly, the lassen Skandal construction examples <strong>in</strong> Vogel’s corpus <strong>in</strong>volve either a passiveor an unaccusative complement—i.e., a complement without an embedded subject. 6• Examples with an embedded subject do appear to be impossible (this needs to be confirmed).(31) Man warf ihm vor… ‘He was accused…”a. se<strong>in</strong>e K<strong>in</strong>der Banken ausrauben haben zu lassenhis children.ACC banks to.rob.INF have.INF to let‘<strong>of</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g let his children rob banks’?? a. *se<strong>in</strong>e K<strong>in</strong>der Banken ausgeraubt haben zu lassenhis children.ACC banks to.rob.PART have.INF to let‘<strong>of</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g let his children rob banks’• Furthermore, no s<strong>in</strong>gle record <strong>of</strong> a Skandal construction with a perception verb was found <strong>in</strong>the corpus. Note that perception verb complements are different from let complements <strong>in</strong> thatthey do not allow the passive construction.(32) a. Sie hat ihn (den Kuchen) essen sehenShe has him (the cake) eat see.IPP‘She has seen him eat (the cake).’b. Er hat den Kuchen essen lassenHe has the cake eat let.IPP‘He has let eat the cake.’#‘He has let the cake eat .’c. #Er hat den Kuchen essen sehenHe has the cake eat see.IPP*‘He has seen eat the cake.’# ‘He has seen the cake eat .’• All <strong>of</strong> the above hence po<strong>in</strong>t to the claim that the Skandal construction is not compatible withan overt AcI subject.New generalization:A vP with a ϕ-complete DP subject blocks the Skandal construction.6 The corpus <strong>in</strong>volves one potential counterexample: Dar<strong>in</strong> wird der "Heimatwerbung" vorgeworfen, Kunden fürdie Affichierung von Plakaten zwar bezahlt haben zu lassen, die Plakate aber nie aufgeklebt zu haben.(I98/AUG.33952 Tiroler Tageszeitung, 26.08.1998). The sentence is ambiguous, but the context seems to favor thesubject <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> Kunden, Further empirical <strong>in</strong>vestigation is necessary to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether examples <strong>of</strong> thissort are <strong>in</strong>deed acceptable (to my judgment they are not when a clear subject <strong>in</strong>terpretation is <strong>in</strong>tended).19

5.3 Towards an account—word order aga<strong>in</strong>• Frisian and German are alike <strong>in</strong> that the order <strong>of</strong> verbs is fully or partially <strong>in</strong>verted.• Claim made here: word order differences can be the result <strong>of</strong> PF-l<strong>in</strong>earization or syntacticmovement.• One further property (Vogel 2009): Skandal construction occurs only <strong>in</strong> the 3-1-2 order.(33) a. ohne es haben verh<strong>in</strong>dern zu können 1-3-2without it have.INF prevent.INF to can.IPPb. *ohne es haben verh<strong>in</strong>dert zu können *Skandal 1-3-2without it have.INF prevent.PART to can.IPP• How is the 3-1-2 word order derived? Assum<strong>in</strong>g that PF-l<strong>in</strong>earization applies only to sisternodes, this word order cannot be derived by simple head » complement l<strong>in</strong>earization choices.(34) 1 [ 2 [3]]]a. 1 before 2P; 2 before 3P: 1-2-3 c. 1 after 2P; 2 before 3P: 2-3-1b. 1 before 2P; 2 after 3P: 1-3-2 d. 1 after 2P; 2 after 3P: 3-2-1• <strong>Wurmbrand</strong> (2004a, b, 2006a): Some verb cluster reorder<strong>in</strong>g is post-syntactic, some syntactic;3-1-2 and 2-1-3 are syntactic.• The German Skandal construction provides further support for this approach.• Assum<strong>in</strong>g there is no actual PF-movement (only l<strong>in</strong>earization <strong>of</strong> sister nodes), to derive the3-1-2 order, syntactic movement is necessary.Conclusion: The Ge Skandal construction (IPP) is only possible <strong>in</strong> contexts that require syntacticmovement.Hypothesis: Movement is <strong>in</strong> fact necessary to derive the Skandal construction.• How could this hypothesis be confirmed? What would be evidence for the necessity <strong>of</strong> movement<strong>in</strong> the Skandal construction (<strong>in</strong> contrast to non-parasitic constructions)?o Semantic effect: No—none <strong>in</strong> verb clusterso New syntactic relations: Yes—Movement creates new Agree relations, which are reflected<strong>in</strong> the morphological form verbs can take.o Locality restrictions: Yes—I argue that the restriction aga<strong>in</strong>st complete vPs <strong>in</strong> theSkandal construction (but not <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival construction) follows from syntacticconditions on movement, which aga<strong>in</strong> only arise when a ParPar is used—i.e., when anew syntactic Agree relation is to be established.20

(35) GermanAuxP3VP AuxP 3ModP 3have Mod … t VPcan.IPPdo.PART AuxHow could movement creat<strong>in</strong>g the 3-1-2 orderbe tied to the licens<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> participles?5.4 German participles are differentMa<strong>in</strong> assumptions:o German participles are lexically valued—uT: perf [see below for motivation]o A particular T val can be <strong>in</strong>serted only once with<strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle T-doma<strong>in</strong> (TP).o If V is <strong>in</strong>serted valued, Aux cannot be <strong>in</strong>serted valued (but, <strong>of</strong> course, Aux will stillbe <strong>in</strong>terpretable); hence Aux—iT: [__].• Ma<strong>in</strong> outcome: In German, Aux becomes dependent on the participle; the system is still differentfrom, e.g., a Pesetsky and Torrego (2007) system, however, <strong>in</strong> that Agree is top-down(which will force movement <strong>of</strong> participles).Derivation <strong>of</strong> the Skandal construction [uT on Mod ignored; see IPP](36) a. ohne es verh<strong>in</strong>dert haben zu können German: Skandalwithout it prevent.PART have.INF to can.IPP have » can‘without hav<strong>in</strong>g been able to prevent it’ [Vogel 2009]b. CP3C TPwithout 3T AuxPiT: ∅ 3VP Aux’uT: perf 3@ Aux ModPiT: [perf] 3uT: [∅] Mod vPDetails:iT: mod 3PRO v’• VP-movement: possible s<strong>in</strong>ce vP is not acomplete phase (PRO); movement doesnot have to go through Spec,vP.• After VP-movement, VP can value the iT<strong>of</strong> Aux (note aga<strong>in</strong> that Agree is not def<strong>in</strong>edas a relation between two heads).• F<strong>in</strong>ally, the uT: [__] <strong>of</strong> Aux is valued bythe iT <strong>of</strong> T.3v t VP21

• How is valuation by T across the valued VP possible? By assumption, only <strong>in</strong>terpretable featuresblock Agree. This seems necessary <strong>in</strong> any account, s<strong>in</strong>ce moved VPs never block Agreerelations between T & other elements.Locality <strong>of</strong> Agree (repeated):iii. There is no γ with a valued <strong>in</strong>terpretable feature F such that γ commands α and is c-commanded by β.Some technical details• Why can’t VP value both the iT: [__] and the uT: [__] <strong>of</strong> Aux (hence wrongly creat<strong>in</strong>gAux.PERF)?• At the moment, I can only stipulate that this is impossible, that is, an iT: [__] and a uT: [__]<strong>of</strong> the same head cannot be valued by the same feature. Look<strong>in</strong>g at the various feature valuationcontexts that have been proposed, this seems to be correct. But I have no answer yet forwhy this is the case.• What guarantees that iT: [__] is valued by the verb (i.e., the element hav<strong>in</strong>g the uT: perf) andnot some other iT feature above Aux? Answer: If it wouldn’t be uT: perf, then uT: perfwould not be connected to any iT: perf feature. I follow Pesetsky and Torrego (2007) <strong>in</strong> theassumption that each valued feature must be semantically <strong>in</strong>terpreted <strong>in</strong> some location (cf.their Thesis <strong>of</strong> Radical Interpretability, attributed to Brody 1997). In contrast to Pesetsky andTorrego (2007), however, and more <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with Bošković (To appear), the current frameworkdoes not entail that this pr<strong>in</strong>ciple imposes a condition on Spell-Out (a uT: val that is not<strong>in</strong> an Agree relation with an iT: val will not cause the derivation to crash). Rather, it appearsthat this pr<strong>in</strong>ciple is <strong>of</strong> a more global nature. I leave open here where (and how) exactly thispr<strong>in</strong>ciple applies.*Skandal construction with complete vPs(37) *weil er es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dert hat können *Skandal (3-1-2)s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not prevent.PART has can.IPP OK: prevent.INF‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has not been able to prevent it’• This restriction can now be accounted for with one additional assumption: (a slightly differentversion <strong>of</strong>) Antilocality (Abels 2003): Spell-Out doma<strong>in</strong>s are frozen.• If the vP conta<strong>in</strong>s a DP-subject, the vP is complete, and the VP becomes a frozen Spell-Outdoma<strong>in</strong>. Movement impossible.• Movement <strong>of</strong> VPs that are note Spell-Out doma<strong>in</strong>s (yet) is possible; <strong>in</strong> essence, movement <strong>of</strong>VP across a DP subject is excluded.22

(38) * TP3T AuxPiT: pres 3Aux ModPiT: [__] 3uT: [pres] Mod vPiT: mod 3DP v’3v VP@VuT: perf• Possible movement: vP; buteven if V v, the features <strong>of</strong>V will not be part <strong>of</strong> the vP(XP conta<strong>in</strong>s only the features<strong>of</strong> its head, not <strong>of</strong> headsadjo<strong>in</strong>ed to its head).• iT: [__] <strong>of</strong> Aux cannot bevalued (correctly), and uT:perf will not be connected toany <strong>in</strong>terpretable version <strong>of</strong>that feature.• Same for the causative examples(39) * AuxP3Aux vP1iT: [__] 3PRO v1’3v1 vP2let 3iT: caus DP v2’3v2 VP@VuT: perf• To value Aux, the embeddedVP has to move above theAuxP.• The higher vP1 is not a problem,as the examples <strong>in</strong>volvednon-f<strong>in</strong>ite let predicates.• However, movement <strong>of</strong> theembedded VP out <strong>of</strong> a vPwith a DP subject is impossible:vP2 is a completephase, and the embedded VPthus frozen.• Omitt<strong>in</strong>g the embedded subject (as <strong>in</strong> the let passive construction), on the other hand, allowsthe embedded VP to move, and hence the Skandal construction.How then is the regular <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival construction possible?(40) a. weil er es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dern hat können 3-1-2s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not prevent.INF has can.IPP‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has not been able to prevent it’b. weil er se<strong>in</strong>e K<strong>in</strong>der Banken ausrauben hat lassen 3-1-2s<strong>in</strong>ce he his children.ACC banks to.rob.INF have.INF let‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has let his children rob banks’• The order 3-1-2 entails syntactic movement; I propose that <strong>in</strong> this construction, it is the vPthat moves (which, as mentioned above, is possible <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple).23

• S<strong>in</strong>ce the ma<strong>in</strong> verb is not a participle, it does not have a valued uT: perf, and hence does notneed to value Aux.• But: how is Aux licensed <strong>in</strong> this construction? To see how the features are licensed <strong>in</strong> the IPPconstruction, we now really need to get <strong>in</strong>to the details <strong>of</strong> participles and the IPP.5.5 What’s up with participles <strong>in</strong> German (and the IPP)?Suggested above:• Ge, Du: Aux iT: [__] V uT: perf• Fr, Sw: Aux iT: perf V uT: [__]• This then entails the opposite Agree relations for these languages, and accounts for the ma<strong>in</strong>differences <strong>in</strong> the distribution <strong>of</strong> ParPars.• Initial support for the reverse Agree relation (Part » Aux) is provided by the word order <strong>of</strong>Aux-Part constructions across West-<strong>Germanic</strong>: In all the languages below, participles canprecede the Aux, even when the language otherwise has a basic 1-2-3 order <strong>in</strong> verb clusters(see <strong>Wurmbrand</strong> 2004a, 2006a and references there<strong>in</strong>):Verb clusters with two verbal elementsLanguage ge- AUXILIARY-PARTICIPLE MODAL-INFINITIVEAfrikaans yes 2-1 1-2Dutch (1=f<strong>in</strong>ite) yes 2-1, 1-2 1-2, 2-1Dutch (1=non-f<strong>in</strong>ite) yes 2-1, 1-2 1-2Frisian no 2-1 2-1Standard German yes 2-1 2-1Swiss yes 2-1 2-1, 1-2West Flemish yes 2-1 1-2Is there someth<strong>in</strong>g about participles <strong>in</strong> German that could motivate this difference?• Yes: German participles are circumfixal—ge-stem-en-/t; phonology permitt<strong>in</strong>g, the prefix geisobligatory. That is, a participle consists <strong>of</strong> two parts, both <strong>of</strong> which be<strong>in</strong>g relevant.• The suffix (participle <strong>morphology</strong>) should be licensed <strong>in</strong> the same way as <strong>in</strong> Fr, Sw, E: i.e.,via a uT: [__] that needs to be valued.• But what about the prefix? Suggestion: the prefix is not dependent (or only <strong>in</strong>directly) on thesyntactic context; rather it seems plausible to consider it a special lexical item <strong>in</strong> German (aswell as other West-<strong>Germanic</strong> languages; see below) that is <strong>in</strong>herently valued as a participle. Ithus assume the follow<strong>in</strong>g structure <strong>of</strong> participles (it does not seem to be relevant whether thestructure is formed <strong>in</strong> the lexicon or via some expanded low VP-structure):(41) a. Ge, Du, WF, Af, Sw b. E, Fr, Sw…VV2 [uT: __]ge- V[uT: perf] [uT: __]24

[Aside: Note that all participles will be assumed to comb<strong>in</strong>e with ge-, even those that cannot use theprefix overtly due to phonological restrictions (<strong>in</strong> German, there is a purely phonological constra<strong>in</strong>tthat requires that prefixes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g ge-, attach to verbs with <strong>in</strong>itial stress; cf. (*ge)marschiert;(*ge)bekommen. In these cases, ge-, or rather its features, are still present structurally, but the lexicalitem ge- is deleted <strong>in</strong> post-syntactic phonology <strong>in</strong> accordance with the prefix rule.)]• This cuts the pie correctly: Sw, Fr do not have prefixal participles, hence the verb comes unvalued;Ge, Du do have prefixal participles, hence the verb comes valued.• Moreover, this view allows us to make sense <strong>of</strong> the IPP.Now, the IPP: An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g (yet <strong>of</strong>ten ignored) generalization• Lange (1981), Vanden Wyngaerd (1994), Hoekstra (1997): IPP is only found <strong>in</strong> languagesthat have prefixal (circumfixal) participles.• The assumption that ge-participles come with a valued uT allows us to implement this generalization.(42) a. weil er es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dern hat können 3-1-2s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not prevent.INF has can.IPP‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has not been able to prevent it’b. weil er es nicht hat verh<strong>in</strong>dern können 1-3-2s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not hs prevent.INF can.IPP‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has not been able to prevent it’(43)TP2T AuxPiT: pres 2Aux ModPiT: perf 2Mod vPiT: mod @*uT: perf VuT: [__] uT: [mod]Derivation:• Assumption: A s<strong>in</strong>gle head cannot come withtwo valued features <strong>of</strong> the same type (i.e., nottwo valued T-features).• This entails that functional modals, which have avalued iT, cannot also have a valued uT.• Insertion <strong>of</strong> uT: perf (ge-) <strong>in</strong> Mod is hence impossible.• Hav<strong>in</strong>g not <strong>in</strong>serted any valued perf feature, allowsthe <strong>in</strong>sertion <strong>of</strong> iT: perf <strong>in</strong> Aux.IPP• Mod — uT:[__] gets valued perf by Aux• But s<strong>in</strong>ce uT: [perf] does not correspond to a lexical item <strong>in</strong> ge- languages, no participle canbe <strong>in</strong>serted.• uT: [perf] is then exceptionally deleted, and the default <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive is <strong>in</strong>serted.• In languages, where participles are not circumfixal, uT: [perf] is realized as a participle andthere would be no reason to delete uT: [perf]. Thus IPP does not occur <strong>in</strong> those languages.Word order• 1-3-2: PF-l<strong>in</strong>earization (<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive before IPP)• 3-1-2: movement <strong>of</strong> vP above Aux; Aux is already valued, so, no issue <strong>of</strong> unvalued iT.25

Further support—Lexical Mod• The <strong>in</strong>sertion <strong>of</strong> uT: perf <strong>in</strong> Mod is blocked s<strong>in</strong>ce the head already has a valued feature.• Modals only have iT when they are functional; lexical Modal Vs do not have an iT.• Correct prediction: Lexical modals (e.g., modals followed by a DP) can occur as participles.(44) Er hat Late<strong>in</strong> gekonntHe has Lat<strong>in</strong> can.PART‘He could (speak) Lat<strong>in</strong>.’Further support—werden• There is one verb <strong>in</strong> German, werden ‘become’, which has two participial forms—one with,and one without ge- (stress is the same on both verbs, hence the ge-less version is not stressrelated):geworden; worden (note the vowel change, which makes this clearly a participle anddifferent from the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive).• As predicted, geworden occurs as a ma<strong>in</strong> verb (valued uT: perf possible), and worden <strong>in</strong>functional contexts (valued uT: perf not possible, but uT: perf can be realized due to the lack<strong>of</strong> ge- <strong>in</strong> this verb).(45) a. Hans ist grün geworden / *wordenJohn is green ge-become.PART / *∅-become.PART‘John turned green’b. Hans ist gewählt *geworden / wordenJohn is elected *ge-become.PART / ∅-become.PART‘John got elected.’5.6 Putt<strong>in</strong>g everyth<strong>in</strong>g togetherF<strong>in</strong>al piece <strong>of</strong> evidence—Skandal only <strong>in</strong> the 3-1-2 order• So far, we have seen how the Skandal construction <strong>in</strong> the 3-1-2 order is derived and why thisconstruction is restricted to cases with non-f<strong>in</strong>ite Aux.• One issue rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is to see how the account excludes Skandal constructions <strong>in</strong> orders otherwisepossible, such as the 1-3-2 order below (repeated).(46) a. ohne es haben verh<strong>in</strong>dern zu können 1-3-2without it have.INF prevent.INF to can.IPPb. *ohne es haben verh<strong>in</strong>dert zu können *Skandal 1-3-2without it have.INF prevent.PART to can.IPPLet’s go through the potential derivations• IPP: Mod needs to be functional (recall that ma<strong>in</strong> V modals do occur as participles).• This leaves two options:26

Summary <strong>of</strong> featuresVerb Features PFwerden uT: perf + uT: [perf] gewordenuT: [perf]wordenhelfen uT: perf + uT: [perf] geholfen* uT: [perf] No form; *holfen; competes with uT: perf + uT: [perf]wollen uT: perf + uT: [perf] gewolltuT: [perf]No form, but deletion <strong>of</strong> uT possible (IPP) s<strong>in</strong>ce nobetter alternativeWhat has done the work?• Crucial difference between Sw/Fr & Ge: ParPar <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ite Aux contexts (examples repeated).(48) a. *weil er es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dert hat können Ge *Skandal (3-1-2)s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not prevent.PART has can.IPP OK: prevent.INF‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has not been able to prevent it’b. Jeg hadde villet lest boka Norwegian ParParI had want.PART read.PART book.DEF‘I would have liked to read the book.’ [Wiklund 2001, 2005, 2007]c. ?dat er dat dien k<strong>in</strong>nen hie Frisian ParParthat he that do.PART can.PART had‘that he had been able to do it’[J. Hoekstra, p.c.]• Aux with iT: [__]: requires movement <strong>of</strong> VP above Aux to license Aux; this is only possiblewhen there VP does not cross any complete vP; locality is the major difference betweenSkandal construction & the downward parasitic participles <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian & Frisian.• Aux with iT: perf (as <strong>in</strong> Swedish/Norwegian, Frisian): <strong>in</strong> German only possible when there isa functional modal (or more specifically, when Aux values only a functional modal; as soonas Aux values a ma<strong>in</strong> verb, that option is excluded); Reason: <strong>in</strong>sertion <strong>of</strong> ge- uT: perf is lesscostly s<strong>in</strong>ce it does not require feature deletion, and hence required.• A structure with a functional modal, however, does not allow ParPars (recall that Aux cannotvalue the ma<strong>in</strong> verb across a functional Mod); VP-movement would not help, s<strong>in</strong>ce valuation<strong>of</strong> V by Aux is <strong>in</strong>sufficient to realize a verb as a participle, due to the lexical restriction <strong>of</strong>participles requir<strong>in</strong>g ge-.5.7 Some loose ends <strong>of</strong> the Skandal construction5.7.1 ParPars <strong>in</strong> lexical modal constructions• There is one construction that occurs <strong>in</strong> the 3-<strong>in</strong>itial (i.e., Part » Aux) order: non-IPP constructions.• The empirical status <strong>of</strong> this construction is somewhat controversial.28

• Bader and Schmid (2009) show (via experiments) that this construction is not well-acceptedby native speakers (only about 17%), but it is <strong>of</strong>ten cited <strong>in</strong> the literature, and it did yield asignificant number <strong>of</strong> hits <strong>in</strong> Vogel’s corpus search (see above).• Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, a ParPar construction is allowed; but as before, the participle is entirely impossiblewhen Aux is f<strong>in</strong>ite.(49) a. ohne helfen gekonnt zu haben 3-2-1 (non IPP)without help.INF can.PART to have‘without hav<strong>in</strong>g been able to help’b. ohne geholfen gekonnt zu haben ParPar 3-2-1without help.PART can.PART to have‘without hav<strong>in</strong>g been able to help’Ich h<strong>of</strong>fe, geholfen gekonnt zu haben.‘I hope to have been able to help’This construction yields numerous hits on a Google searchc. *weil er geholfen gekonnt hat *ParPar; Aux = f<strong>in</strong>s<strong>in</strong>ce he help.PART can.PART has OK if help.INF‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he has been able to help’• If these data are confirmed on a broader basis, the follow<strong>in</strong>g revised generalizations hold forparasitic participles <strong>in</strong> German:• vP with an overt DP subject blocks the Skandal construction.• The participle must precede Aux (3-1-2 or 3-2-1).• The German ParPar is not restricted to IPP constructions.• (49)a: modal must be ma<strong>in</strong> verb (s<strong>in</strong>ce it occurs as a participle); to derive an <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itive, anembedded iT: irr is required (see section 5.5).• (49)b,c: the contrast strongly suggests that the ParPar is licensed like <strong>in</strong> the Skandal construction(movement) and not like <strong>in</strong> the Frisian/Swedish/Norwegian ParPar.• The good news: s<strong>in</strong>ce the modal and ma<strong>in</strong> verbs are ge-participles, they must be <strong>in</strong>serted withuT: perf, and Aux with iT: [__]. To value the Aux feature, movement is necessary, and thusthe by now familiar locality restriction is predicted (only PRO-vPs allow VP movement).• But: how are two participles possible? To end up with participial <strong>morphology</strong>, both, the modaland the ma<strong>in</strong> verb need to be <strong>in</strong>serted as lexical verbs with uT: perf. The assumption thatonly one orig<strong>in</strong>ally valued feature is possible per T-doma<strong>in</strong> thus seems to be too strong forthese cases. S<strong>in</strong>ce the data are also not entirely clear yet and need to be confirmed by furtherempirical studies, I leave this issue open for now.5.7.2 Skandal construction <strong>in</strong> some f<strong>in</strong>ite contexts• A Skandal construction seems to be f<strong>in</strong>e, even <strong>in</strong> a f<strong>in</strong>ite context, when there is another modalembedd<strong>in</strong>g the 3-1-2 cluster.29

(50) Er wird es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dert haben können will [3-1-2]He will it not prevent.PART have.INF can.IPP‘He will not have been able to prevent it.’Not: ‘He will not be able to have prevented it.’SW judgment• A quick Google search turned up several <strong>of</strong> these examples.(51) a. Das müsste dir weiter geholfen haben können. Mod [3-1-2]‘That must have been able to help you further.’have » canNot: ‘That must be able to have helped you.’http://www.joomlaportal.de/allgeme<strong>in</strong>e-fragen-zu-mambo-4-5-0/2122-actualizedgerman-langfile-corrected-date-time.htmlb. Suche nach trillian* sollte auch geholfen haben können Mod [3-1-2]‘The search for trillian* should also have been able to help.’have » canNot: ‘The search for trillian* should also be able to have helped.’http://www.og<strong>of</strong>orum.de/1-1-forum/icq-msn-forum/2871-ogo-im-zu-trillian-leerenachrichten/c. Solltest du de<strong>in</strong>er Oma damit geholfen haben können… Mod [3-1-2]‘Should you have been able to help your grandma…’have » canNot: ‘Should you be able to have helped your grandma…’http://www.onmeda.de/foren/forum-rheuma/mittel-gegen-rheuma/680945/read.html• As for embedded contexts, I also f<strong>in</strong>d the follow<strong>in</strong>g possible (<strong>in</strong> contrast to the examples withf<strong>in</strong>ite Aux, there is no big difference <strong>in</strong> grammaticality between participles and <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives <strong>in</strong>these cases). But further empirical work is needed to confirm this.(52) All <strong>in</strong>tended: ‘s<strong>in</strong>ce he will not have been able to prevent it’a. weil er es nicht verh<strong>in</strong>dert haben können wird [3-1-2] wills<strong>in</strong>ce he it not prevent.PART have.INF can.IPP will.FINb. weil er es nicht wird verh<strong>in</strong>dert haben können will [3-1-2]s<strong>in</strong>ce he it not will.FIN prevent.PART have.IPP can.INF• Solution: the highest modal is a lexical verb embedd<strong>in</strong>g the 3-1-2 cluster. The lower modal(can) must be functional s<strong>in</strong>ce it occurs <strong>in</strong> the IPP, but noth<strong>in</strong>g seems to exclude generat<strong>in</strong>gthe highest modal as a lexical verb.• The subject is then generated as the subject <strong>of</strong> the highest modal, and the embedded structure<strong>in</strong>volves a PRO subject. VP-movement with<strong>in</strong> the 3-1-2 cluster is thus possible.• The different orders are the result <strong>of</strong> different PF-l<strong>in</strong>earizations between will and its complement(which is also possible <strong>in</strong> simple clusters).30

5.7.3 Dutch• It seems standard Dutch does not have any parasitic constructions. Dutch is like German <strong>in</strong>that it has ge-participles; hence the k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> parasitic construction we would expect is theSkandal construction.• One major difference between Dutch and German concerns the possible word orders <strong>in</strong> verbclusters: Aux»Mod»V (IPP) constructions are only possible <strong>in</strong> the 1-2-3 order <strong>in</strong> Dutch.• This may be the reason for why the Skandal construction is not possible: to derive that construction,3-1-2 movement is necessary. If that movement is blocked <strong>in</strong>dependently, parasiticparticiples are predicted to be impossible.• Caveat: participles do move <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> constructions <strong>in</strong> Dutch. Thus, it is necessary to tie verbcluster movement to the type <strong>of</strong> construction (Aux»Mod»V; IPP), rather than the <strong>morphology</strong><strong>of</strong> the verbs <strong>in</strong>volved.• <strong>Parasitic</strong> participles do exist <strong>in</strong> some varieties <strong>of</strong> Dutch (e.g., the Stell<strong>in</strong>gwerf dialect), andfurther <strong>in</strong>vestigation is necessary to establish if the restrictions proposed <strong>in</strong> this talk carryover to these dialects.6. SOME THOUGHTS ON SWEDISH TENSE COPYING• At the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g, we have seen that Swedish allows certa<strong>in</strong> tense copy<strong>in</strong>g constructions.• Wiklund (2005, 2007) argues that tense copy<strong>in</strong>g is only possible:o <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives that allow o (morphologically, o is a reduced form <strong>of</strong> och ‘and); cf. try(o-complement possible) vs. modals (o-complement impossible)o <strong>in</strong> semantically tenseless <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives; cf. try vs. decideo <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives without the (<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival) complementizer atto <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itives without a nom<strong>in</strong>ative subjecto when there are no embedded TP, vP-modifiers, or float<strong>in</strong>g quantifiers associated withan embedded subject.(53) a. Jeg hadde villet lest boka ParParI had want.PART read.PART book.DEF‘I would have liked to read the book.’b. *Han kunde (*o) läste *Tense copy<strong>in</strong>gHe can.PAST (*o) read.PAST‘He could read’c. Han prövade o/*att (*han) stekte en fisk OK Tense copy<strong>in</strong>gHe try.PAST o/*att (*he) fry.PAST a fish (Restructur<strong>in</strong>g)‘He tried to fry a fish’d. *Han beslutade o stekte en fisk *Tense copy<strong>in</strong>gHe decide.PAST o fry.PAST a fish (non-restructur<strong>in</strong>g)‘He decided to fry a fish’31

Wiklund’s account:• No coord<strong>in</strong>ation structure: non-ATB movement from o-complement is possible; movement<strong>of</strong> the entire o-complement is possible (but requires do); o tracks the behavior <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itivalcomplementizer rather than coord<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> multiple o-contexts.• o-complement is a CP with underspecified C, T, v (ignor<strong>in</strong>g partial copy<strong>in</strong>g).• Matrix T values the embedded T (via Agree, but details are left open).• Ban aga<strong>in</strong>st embedded TP, vP modifiers, FQs: assumption that “unvalued functional heads donot license modifiers”.Back to the current approach• Unfortunatly, Wiklunds Agree account is not compatible with the approach suggested here.S<strong>in</strong>ce the matrix predicate <strong>in</strong>volves a complete vP, the matrix T can only see down to v, andnot <strong>in</strong>to the complement <strong>of</strong> v.• Wiklund’s arguments aga<strong>in</strong>st a full coord<strong>in</strong>ation structure are compell<strong>in</strong>g; on the other hand,what’s not accounted for under a simple complementation structure is the fact that tensecopy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volves the element o, which is homophonous to conjunction (and, as Wiklund argues,cannot be assumed to be a colloquial version <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itival complementizer att).• Similarly, the fact that embedded TP, vP modifiers, as well as float<strong>in</strong>g quantifiers are impossiblemight be taken to show that the o-complement does not <strong>in</strong>volve TP, vP, and an embeddedsubject.At this po<strong>in</strong>t, I see two (very different) ways for how to approach tense copy<strong>in</strong>g constructions.Further research is needed it see whether either <strong>of</strong> these approaches is tenable.Inf<strong>in</strong>itive <strong>in</strong>volves a uT: pres/past• This would allow us to basically keep Wiklund’s CP-structure and account for the fact thatthe embedded verb occurs with morphological tense, but this tense is not <strong>in</strong>terpretable.• Ma<strong>in</strong> challenge: ensure that the embedded uT: pres/past is dependent on the matrix T andthat tense copy<strong>in</strong>g is blocked by <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g iTs, such as <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g:(54) *T » T/C » TiT: past iT: pres/∅ uT: past• The Thesis <strong>of</strong> Radical Interpretability may do some <strong>of</strong> the work here; but locality will be thema<strong>in</strong> challenge s<strong>in</strong>ce the matrix T can never Agree with anyth<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> the complement <strong>of</strong>v. This pr<strong>in</strong>ciple thus could not be a condition that has to be met by Spell-Out, rather it mustbe possible to meet it via some version <strong>of</strong> feature shar<strong>in</strong>g à la Pesetsky and Torrego (2007).However, implement<strong>in</strong>g this <strong>in</strong> the current account is not trivial.Non-<strong>in</strong>terpretable coord<strong>in</strong>ation structure• Tense copy<strong>in</strong>g constructions <strong>in</strong>volve v’-coord<strong>in</strong>ation, but <strong>in</strong> contrast to ‘true’ coord<strong>in</strong>atestructures where the coord<strong>in</strong>ator is an element with an <strong>in</strong>terpretable “and” feature, o <strong>in</strong> tensecopy<strong>in</strong>g construction is not <strong>in</strong>terpretable, but rather a uF: val (&).32