Number 8 - Geological Curators Group

Number 8 - Geological Curators Group

Number 8 - Geological Curators Group

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

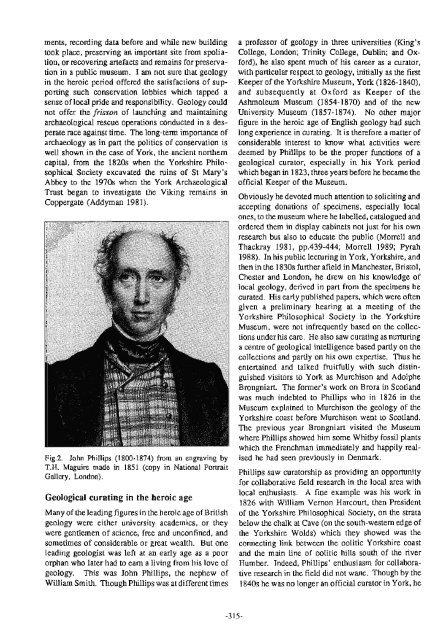

ments, recording data before and while new buildingtook place, preserving an important site from spoliation,or recovering artefacts and remains for preservationin a public museum. I am riot sure that geologyin the heroic period offered the satisfactions of supportingsuch conservation lobbies which tapped asense of local pride and responsibility. Geology couldnot offer the frisson of launching and maintainingarchaeological rescue operations conducted in a desperaterace against time. The long-term importance ofarchaeology as in part the politics of conservation iswell shown in the case of York, the ancient northemcapital, from the 1820s when the Yorkshire PhilosophicalSociety excavated the n ins of St Mary'sAbbey to the 1970s when the York ArchaeologicalT~st began to investigate the Viking remains inCoppergate (Addyman 1981).Fig.2. John Phillips (1800-1874) from an engraving byT.H. Maguire made in 1851 (copy in ~ational ~o&ajtGallery, London).<strong>Geological</strong> curating in the heroic ageMany of theleading figures in the heroic age of Britishgeology were either university academics, or theywere gentlemen of science, free and unconfined, andsometimes of considerable or great wealth. But oneleading geologist was left at an early age as a poororphan who later had to earn a living from his love ofgeology. This was John Phillips, the nephew ofWilliam Smith. Though Phillips was at different timesa professor of geology in three universities (King'sCollege, London; Trinity College, Dublin; and Oxford),he also spent much of his career as a curator,with particular respect to geology, initially as the firstKeeper of the Yorkshire Museum, York (1826-1840),and subsequently at Oxford as Keeper of theAshmoleurn Museum (1854-1870) and of the newUniversity Museum (1857-1874). No other majorfigure in the heroic age of English geology had suchlong experience in curating. It is therefore a maner ofconsiderable interest to know what activities weredeemed by Phillips to be the proper functions of ageological curator, especially in his York periodwhich began in 1823, three years before he became theofficial Keeper of the Museum.Obviously he devoted much attention to soliciting andaccepting donations of specimens, especially localones, to the museum where he labelled, catalogued andordered them in display cabinets not just for his ownresearch but also to educate the public (Morrell andThackray 1981, pp.439-444; Morrell 1989; Pyrah1988). In his public lecturing in York, Yorkshire, andthen in the 1830s further afield in Manchester, Bristol,Chester and London, he drew on his knowledge oflocal geology, derived in part from the specimens becurated. His early published papers, which were oftengiven a preliminary hearing at a meeting of theYorkshire Philosophical Society in the YorkshireMuseum, were not infrequently based on the collectionsunder his care. He also saw curating as nurturinga centre of geological intelligence based partly on thecollections and partly on his own expertise. Thus heentertained and talked fruitfully with such distinguishedvisitors to York as Murchison and AdolpheBrongniart. The former's work on Brora in Scotlandwas much indebted to Phillips who in 1826 in theMuscum explained to Murchison the geology of theYorkshire coast before Murchison went to Scotland.The previous year Brongniart visited the Museumwhere Phillips showed him some Whitby fossil plantswhich the Frenchman immediately and ha~oilvA A . realisedhe had seen previously in Denmark.Phillips saw curatorship as providing an opportunityfor collaborative field research in the local area withlocal enthusiasts. A fine example was his work in1826 with William Vernon Harcourt. then Presidentof the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, on the stratabelow the chalk at Cave (on the south-westem edge ofthe Yorkshire Wolds) which they showed was theconnecting link between the oolitic Yorkshire coastand the main line of oolitic hills south of the riverHumber. Indeed, Phillips' enthusiasm for collaborativeresearch in the field did not wane. Though by the1840s he was no longer an official curator in York, he