NOHSC Symposium on the OHS Implications of Stress - Safe Work ...

NOHSC Symposium on the OHS Implications of Stress - Safe Work ...

NOHSC Symposium on the OHS Implications of Stress - Safe Work ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Copyright Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth <strong>of</strong> Australia 2002ISBN 0 642 70593 3This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under <strong>the</strong>Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any processwithout prior written permissi<strong>on</strong> from AusInfo. Requests andinquiries c<strong>on</strong>cerning reproducti<strong>on</strong> and rights should be addressed to<strong>the</strong> Manager, Legislative Services, InfoAccess Network, GPO Box1920, Canberra City, ACT 2601.

DisclaimerWhile this document is funded by <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g>, it represents <strong>the</strong> views <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> authors <strong>the</strong>mselves. Any statements or proposals c<strong>on</strong>tainedwithin this document do not represent <strong>the</strong> views <strong>of</strong>, and are notnecessarily endorsed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g>, its employees, <strong>of</strong>ficers and agents do not accept anyliability for <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> any acti<strong>on</strong> taken in reliance up<strong>on</strong> or based<strong>on</strong> or in c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> with this document.

C<strong>on</strong>tents<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy 3Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Maureen Dollard, PhDIndividual Difference Factors and <strong>Stress</strong>: A Case Study Paper 58Dr Jim Bright, University <strong>of</strong> New South Wales.Evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Occupati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Stress</strong> Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: An Overview 80Anth<strong>on</strong>y D. LaM<strong>on</strong>tagne, ScD, MA, MEd.<strong>Stress</strong>, Arousal and Fatigue in Repetitive ‘Assembly Line’ <strong>Work</strong>: A Case Study 98Wendy MacD<strong>on</strong>aldMulti-level approaches to stress 124David Morris<strong>on</strong>, University <strong>of</strong> Western AustraliaQueensland Public Sector–Occupati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Stress</strong> Interventi<strong>on</strong> Experience: A Case Study 130Malcolm DouglasExtract from <strong>the</strong> ‘Comparis<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Work</strong>ers’ Compensati<strong>on</strong> Arrangements in AustralianJurisdicti<strong>on</strong>s’ July 2000 138Additi<strong>on</strong>al informati<strong>on</strong> suggested by <strong>the</strong> chairman 157Organisati<strong>on</strong>al interventi<strong>on</strong>s for work stress-A risk management approach: CaseStudies 158Extract from ‘Cases in <strong>Stress</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong>: The Success <strong>of</strong> a Participative and StepwiseApproach’ 165<str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 2

<str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> SYMPOSIUM ON THE <strong>OHS</strong> IMPLICATIONSOF STRESS<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence toPolicyA Case StudyASSOCIATE PROFESSOR MAUREEN DOLLARD, PHDUniversity <strong>of</strong> South AustraliaEXECUTIVE SUMMARYThe Nati<strong>on</strong>al Occupati<strong>on</strong>al Health and <strong>Safe</strong>ty Commissi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Australia commissi<strong>on</strong>ed this paper <strong>on</strong>adverse health effects, key <strong>the</strong>ories, interventi<strong>on</strong>s, and implicati<strong>on</strong>s for policy and practice inrelati<strong>on</strong> to work stress. The nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> workplace is changing rapidly and in <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>text <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>new informati<strong>on</strong> ec<strong>on</strong>omy, globalisati<strong>on</strong>, and <strong>the</strong> introducti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> new technologies, emerging risksfor Australian workers include increased pace <strong>of</strong> work, l<strong>on</strong>ger hours, more emoti<strong>on</strong> work, greatercognitive demands, exposure to violence, increased m<strong>on</strong>itoring, and job insecurity. At <strong>the</strong> same timegreater participati<strong>on</strong> and dialogue between key stakeholders in <strong>the</strong> way new work practices evolve,holds great promise for not <strong>on</strong>ly preventing work stress and promoting health and well-being, but at<strong>the</strong> same time c<strong>on</strong>tributing to job satisfacti<strong>on</strong>, productivity, work meaning, social cohesiveness andcompetitiveness.The aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> paper was to undertake a comprehensive review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> occupati<strong>on</strong>al stress literaturein <strong>the</strong> following areas:• current evidence for <strong>the</strong> health impacts <strong>of</strong> stress;• <strong>the</strong> history and evoluti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> major models <strong>of</strong> how work stress operates,c<strong>on</strong>sidering <strong>the</strong> definiti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> stress employed by <strong>the</strong> different paradigms, and<strong>the</strong>ir limitati<strong>on</strong>s and problems, as well as <strong>the</strong>ir c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s to ourunderstanding;• policy and practical implicati<strong>on</strong>s, with an overview <strong>of</strong> strategies used to identify,assess, and manage stress in <strong>the</strong> workplace.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 3

Evidence for health effectsExposure to stressors does not necessarily cause health problems in all people. While <strong>the</strong> experiencemay be accompanied by feelings <strong>of</strong> emoti<strong>on</strong>al discomfort, and may significantly affect well-being at<strong>the</strong> time, it does not necessarily lead to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> a psychological or physiological disorder.In cases where <strong>the</strong> stressor is prol<strong>on</strong>ged stress may affect health; or it may sensitise a pers<strong>on</strong> too<strong>the</strong>r sources <strong>of</strong> stress by reducing <strong>the</strong>ir ability to cope. Evidence is accumulating that <strong>the</strong> comm<strong>on</strong>assumpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> a relati<strong>on</strong>ship between stressors, <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> stress and poor health appears tobe justified.First <strong>of</strong> all, it is important to understand <strong>the</strong> normal physiological resp<strong>on</strong>se to stress. It is generallyagreed that <strong>the</strong>re are two arousal pathways relevant to <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>se to stress:• <strong>the</strong> hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-cortical arousal system (HPA axis) thatinvolves <strong>the</strong> activati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adrenal cortex by <strong>the</strong> pituitary gland to releasecortisol, into <strong>the</strong> blood.• SNS-adrenal-medullary arousal involves stimulati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adrenal medulla, by<strong>the</strong> hypothalamus acting through sympa<strong>the</strong>tic nervous system (SNS) to releaseadrenalin and SNS synapses to release noradrenalin.When faced with a challenge (a ‘stressor’), complex interacti<strong>on</strong>s and feedback occur between <strong>the</strong>systems. If <strong>the</strong> challenge is short term, <strong>the</strong> initial reacti<strong>on</strong> is adaptive: it enables <strong>the</strong> individual tomobilise energy resources in <strong>the</strong> body to deal with <strong>the</strong> stressor. Comm<strong>on</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>ses are increasedheart rate, increased blood pressure, and more rapid breathing.When <strong>the</strong> stressor is c<strong>on</strong>tinuous (chr<strong>on</strong>ic), severe (e.g. violent act) or with repeated exposure, <strong>the</strong>normal physiological reacti<strong>on</strong> may turn pathological. The individual enters <strong>the</strong> stage <strong>of</strong> resistancewhere different physiological changes occur as <strong>the</strong> individual attempts to withstand <strong>the</strong> stressor. Theresting baseline levels <strong>of</strong> both adrenalin and cortisol are elevated and am<strong>on</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r changes <strong>the</strong>re isa slower return to baseline levels. This indicates a diminished ability to cope physiologically.Finally, if exposure to <strong>the</strong> stressor c<strong>on</strong>tinues, a pers<strong>on</strong> may reach a stage <strong>of</strong> exhausti<strong>on</strong> whereorganic damage can occur.It is assumed that chr<strong>on</strong>ic stress results in an inability to recharge <strong>the</strong> adrenomedullary resp<strong>on</strong>serequired for adaptati<strong>on</strong>. This leads to adrenalin degenerati<strong>on</strong> and to cardiovascular degenerati<strong>on</strong>.Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> elevati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> adrenalin and cortisol may affect cardiovascular health partly via <strong>the</strong>effects <strong>of</strong> horm<strong>on</strong>es <strong>on</strong> blood pressure and serum cholesterol levels.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 4

This paper discusses <strong>the</strong> possible adverse health effects <strong>of</strong> work stress under two headings:• physiological and physical effects, and• psychological and psychiatric effects.Physiological and physical effects <strong>of</strong> stressThe clearest evidence for physical health effects <strong>of</strong> work stressors comes from a number <strong>of</strong>l<strong>on</strong>gitudinal studies which found an elevated risk <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular disease due to job strain.In additi<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Whitehall II study showed a link between low levels <strong>of</strong> job c<strong>on</strong>trol and an increasedrisk for cor<strong>on</strong>ary heart disease. Obesity is also found to be linked to job strain.O<strong>the</strong>r health effects such as asthma, peptic ulcers, and rheumatoid arthritis are thought to resultfrom work stress.Psychological and psychiatric health effectsChr<strong>on</strong>ic strainMost stress models assume that <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> chr<strong>on</strong>ic stress leads to acute reacti<strong>on</strong>s or strainsymptoms in <strong>the</strong> worker which in turn may be precursors to disease or lead to disease.Numerous studies have linked work stress to psychological strain symptoms including:• cognitive effects, such as job dissatisfacti<strong>on</strong> and an inability to c<strong>on</strong>centrate;• affective disorders, including mental health states such as anxiety, anger anddepressi<strong>on</strong>; and• somatic symptoms such as headaches, perspirati<strong>on</strong>, and dizziness.Such c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s may not necessarily be classifiable under recognised psychiatric classificati<strong>on</strong>systems. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s may represent significant functi<strong>on</strong>al disturbances or risks for <strong>the</strong>development <strong>of</strong> clinical disorders.L<strong>on</strong>ger term psychological outcomes may include mental illness and suicide.Behavioural strain may be indicated by <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> alcohol and drugs, including tobacco; reducedwork performance; higher levels <strong>of</strong> absenteeism or sick leave; an increase in industrial accidentsand higher staff turnover.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 5

Besides <strong>the</strong>se outcomes, strain from <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment may spill over into <strong>the</strong> home envir<strong>on</strong>ment,leading to marital problems and o<strong>the</strong>r social issues.Post-traumatic stress disorder<strong>Stress</strong>ors in <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment may present as intense, acute events, bey<strong>on</strong>d normal expectati<strong>on</strong>s.For example, <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> violent incidents, witnessing a robbery, working with abused clients,or dealing with road accidents may be very upsetting or even life threatening.The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual <strong>of</strong> Mental Disorders (DSM-IVTR 2000), and <strong>the</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>alClassificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Diseases (ICD-10) provide <strong>the</strong> criteria for diagnosis <strong>of</strong> post-traumatic stressdisorder (PTSD) including <strong>the</strong> exposure to a traumatic event and <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> sequelaeassociated with that event.Symptoms typically include intrusive recollecti<strong>on</strong>s, dreams, sensitivity to stimuli associated with <strong>the</strong>initial event, and avoidance <strong>of</strong> activities or situati<strong>on</strong>s associated with <strong>the</strong> trauma. A range <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rpsychological c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s may co-exist with PTSD, such as anxiety, depressi<strong>on</strong>, thinking <strong>of</strong> suicide,panic disorder, anti-social pers<strong>on</strong>ality disorder, agoraphobia, and substance abuse. Arguments havebeen made recently that chr<strong>on</strong>ic stressors could also be viewed as a precursor to PTSD, for examplein <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> bullying.In summary, <strong>the</strong> evidence indicates that chr<strong>on</strong>ic stress results in chr<strong>on</strong>ic neuroendocrine andcardiovascular over-arousal, peripheral adrenalin degenerati<strong>on</strong> and cardiovascular degenerati<strong>on</strong>.These physiological changes are presumed to underpin both psychological and physical healthproblems, and <strong>the</strong> well dem<strong>on</strong>strated link between <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment and a range <strong>of</strong> health effectsincluding cardiovascular disease, psychological and psychiatric symptoms.<strong>Work</strong> stress <strong>the</strong>oriesJob stress is defined generally as “<strong>the</strong> harmful physical and emoti<strong>on</strong>al resp<strong>on</strong>ses that occur when <strong>the</strong>requirements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> job do not match <strong>the</strong> capabilities, resources, or needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> worker. Job stresscan lead to poor health and even injury” (NIOSH, 1999).There are many different <strong>the</strong>ories about how work stress arises and how it causes or c<strong>on</strong>tributes toadverse health effects. Though <strong>the</strong>y may differ in emphasis, in many ways <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ories overlap andcomplement each o<strong>the</strong>r. These <strong>the</strong>ories can be grouped in different categories, for example:• stimulus/resp<strong>on</strong>se combinati<strong>on</strong>s;• interacti<strong>on</strong>al vs transacti<strong>on</strong>al models;<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 6

• sociological vs psychological paradigms; and• envir<strong>on</strong>mental vs individual emphasis.This paper discussed four dominant c<strong>on</strong>temporary <strong>the</strong>oretical models <strong>of</strong> work stress, in terms <strong>of</strong>interacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ories and transacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ories.Interacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>oriesThese focus <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> structural features <strong>of</strong> a pers<strong>on</strong>’s interacti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong>ir work envir<strong>on</strong>ment, andinclude:• <strong>the</strong> demand-c<strong>on</strong>trol/support (DC/S) model; and burnout.The DC/S modelThis emphasises <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment. It argues that strain (seen as a c<strong>on</strong>sequence <strong>of</strong> stress) resultsfrom <strong>the</strong> joint effects <strong>of</strong> high job demand and low job c<strong>on</strong>trol. Social support has been added to <strong>the</strong>model; more recently strain effects are exacerbated in c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> low support.BurnoutThe literature <strong>on</strong> burnout emphasises <strong>the</strong> social work envir<strong>on</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> human service workers. Itdescribes a syndrome <strong>of</strong> emoti<strong>on</strong>al exhausti<strong>on</strong>, lack <strong>of</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>al accomplishment anddepers<strong>on</strong>alisati<strong>on</strong> in resp<strong>on</strong>se to chr<strong>on</strong>ic exposure to difficult clients.Empirical tests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> model, however, reveal that strain results more from operati<strong>on</strong>al andorganisati<strong>on</strong>al aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> job than from dealing with difficult clients.Factors involved in <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> strain are seen in this model to include:• work overload;• lack <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol;• insufficient reward;• breakdown <strong>of</strong> community;• absence <strong>of</strong> fairness; and• value c<strong>on</strong>flict.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 7

Recent formulati<strong>on</strong>s have focused <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> a mismatch between <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> job,and highlighted <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> more positive engaging aspects <strong>of</strong> healthy work combinati<strong>on</strong>s.Transacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>oriesThese focus <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> cognitive processes and emoti<strong>on</strong>al reacti<strong>on</strong>s associated with <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>’sinteracti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong>ir envir<strong>on</strong>ment. Transacti<strong>on</strong>al models are in a sense a development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>interacti<strong>on</strong>al model and are largely c<strong>on</strong>sistent with <strong>the</strong>m.Transacti<strong>on</strong>al models include:• <strong>the</strong> effort-reward (ERI) model; and• <strong>the</strong> cognitive-phenomenological <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> stress.Effort-reward imbalance (ERI) modelThe ERI model builds <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> idea that workers expend effort at work and expect as part <strong>of</strong> a sociallynegotiated process, an adequate reward (m<strong>on</strong>ey, esteem, status c<strong>on</strong>trol). According to <strong>the</strong> model,when an imbalance occurs, strain can result. The ERI model also specifies a pers<strong>on</strong>al variable asvery important in <strong>the</strong> model. Referred to as over-commitment, it is argued that some people have <strong>the</strong>tendency to c<strong>on</strong>tribute large efforts to <strong>the</strong> task, and in a sense create an extra (intrinsic) demand thatcan exacerbate <strong>the</strong> imbalance.Cognitive-phenomenological modelThis model <strong>of</strong> stress emphasises pers<strong>on</strong>al appraisal and coping resp<strong>on</strong>ses as important in <strong>the</strong> stressprocess. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, individuals perceive a situati<strong>on</strong> as stressful, and appraise <strong>the</strong>ir ownresources for coping with it. If <strong>the</strong>y feel <strong>the</strong>ir ability to cope is not adequate to resolve or deal with<strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong>, this results in psychological strain.These <strong>the</strong>ories each explain important aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work stress picture. The models differ, however,in that some put more emphasis <strong>on</strong> those aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment which are able to beinfluenced by management, while o<strong>the</strong>rs view <strong>the</strong> individual, and <strong>the</strong> individual’s coping strategies,as <strong>the</strong> key to dealing with <strong>the</strong> issue. This is clearly a critical difference, since if <strong>the</strong> problem isdefined as a deficiency in an individual’s coping mechanisms, management is less likely to c<strong>on</strong>cludethat a re-organisati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> work practices is called for.The paper expands <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>ories, and discusses <strong>the</strong>ir implicati<strong>on</strong>s for workplace practice. Inparticular <strong>the</strong> DCS and ERI models have provided key elements for stress interventi<strong>on</strong> in majorinternati<strong>on</strong>al work stress policy frameworks, because <strong>the</strong>y clearly identify work dimensi<strong>on</strong>s, and<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 8

ecause <strong>the</strong>y are clearly evidence based. Even when pers<strong>on</strong>al dispositi<strong>on</strong> is implicated, workcharacteristics exert a str<strong>on</strong>g influence <strong>on</strong> health and productivity outcomes.Difficulties emerging from testing <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ories, toge<strong>the</strong>r with identified organisati<strong>on</strong>al problems,have given rise to more active, participatory, research methodologies. These include managementapproaches that use multiple <strong>the</strong>ories and intend to develop new local <strong>the</strong>ory. C<strong>on</strong>temporaryapproaches to <strong>the</strong> measurement <strong>of</strong> work stress in organisati<strong>on</strong>s call for multidisciplinary strategies,and <strong>the</strong> inclusi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> relevant value positi<strong>on</strong>s.Sources <strong>of</strong> work stressAn impressive body <strong>of</strong> research has delineated certain features <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment that <strong>the</strong> vastmajority <strong>of</strong> workers find stressful. The paper explores a range <strong>of</strong> sources <strong>of</strong> work stress, includingphysical and psychosocial stressors, stressful features <strong>of</strong> jobs, individual factors and lifestyle, genderdifferences, socio-ec<strong>on</strong>omic status and job c<strong>on</strong>trol, workplace violence, <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> supervisorand emerging issues such as globalisati<strong>on</strong> and o<strong>the</strong>r pressures <strong>on</strong> workers.Implicati<strong>on</strong>s for policy and practiceStrategies for identifying, assessing and managing stress in <strong>the</strong> workplace may be implemented at <strong>the</strong>individual level, <strong>the</strong> organisati<strong>on</strong>al level or <strong>the</strong> nati<strong>on</strong>al level. The paper presents an overview <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se strategies, as <strong>the</strong>y emerge from a review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature. It c<strong>on</strong>cludes that <strong>the</strong>re isc<strong>on</strong>siderable scope for tackling <strong>the</strong> problem through organisati<strong>on</strong>al interventi<strong>on</strong>s.Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s arising from a c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research encompass a number <strong>of</strong> policies topromote whole <strong>of</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong>al approaches, healthy organisati<strong>on</strong>s, sustainable organisati<strong>on</strong>s andethical acti<strong>on</strong>. These include <strong>the</strong> following;• Focus <strong>on</strong> primary preventi<strong>on</strong>;• Ensuring proper training and career development for improved P-E fit;• Ensuring optimum c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s for <strong>the</strong> introducti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> new technologies;• <strong>Work</strong>er involvement in planning and change;• Equal opportunities and fairness; and• Interventi<strong>on</strong>s to improve work design.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 9

The latter could include a focus <strong>on</strong> organisati<strong>on</strong> and management to improve communicati<strong>on</strong>s andstaff involvement and c<strong>on</strong>trol over work; develop a culture in which staff are valued; structuresituati<strong>on</strong>s to promote formal and informal social support within <strong>the</strong> workplace; evaluate workdemands and staffing levels; evaluate supervisor/manager performance; and reduce violentexposures.Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for policies at <strong>the</strong> nati<strong>on</strong>al level relate to:• priorities for research• <strong>the</strong> need for more comprehensive data and nati<strong>on</strong>al m<strong>on</strong>itoring systems• examinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> legislati<strong>on</strong>• a clearing house for all relevant informati<strong>on</strong> and educati<strong>on</strong>al materials• more educati<strong>on</strong> and training <strong>on</strong> work stress and interventi<strong>on</strong>s for allstakeholders.Fur<strong>the</strong>r, guidelines for best-practice in organizati<strong>on</strong>al stress interventi<strong>on</strong> are provided. Theserecommendati<strong>on</strong>s seem relevant and applicable in <strong>the</strong> Australian work envir<strong>on</strong>ment today.C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>We would do well to remember that <strong>the</strong> ‘job’ c<strong>on</strong>cept has <strong>on</strong>ly a 200 year history and that jobs<strong>the</strong>mselves and <strong>the</strong>ir inherent structures are human c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>s, not immutable, but capable <strong>of</strong>c<strong>on</strong>tinuous improvement. As demands for quality and productivity increase and new demandsemerge, such as emoti<strong>on</strong>al and cognitive demands, work management will require change. <strong>Work</strong>erswill require more varied organisati<strong>on</strong>al resp<strong>on</strong>ses to assist <strong>the</strong>m to cope with old, new, and emergingrisks as well as high performance. Policies and strategies for c<strong>on</strong>tinuous m<strong>on</strong>itoring and dialoguebetween <strong>the</strong> full range <strong>of</strong> stakeholders is imperative.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 10

INTRODUCTIONThis paper aims to provide a comprehensive review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> occupati<strong>on</strong>al stress literature in <strong>the</strong>following areas:• current evidence for <strong>the</strong> health impacts <strong>of</strong> stress;• <strong>the</strong> major models <strong>of</strong> work stress, <strong>the</strong>ir strengths, limitati<strong>on</strong>s, andc<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s to our understanding; and• policy and practice implicati<strong>on</strong>s, with an overview <strong>of</strong> strategies used toidentify, assess, and manage stress in <strong>the</strong> workplace.CURRENT EVIDENCE FOR HEALTH IMPACTS OF WORK STRESS<strong>Stress</strong> is c<strong>on</strong>sidered to arise from exposure to stressors, but it is important to establish from<strong>the</strong> outset that this does not necessarily cause health problems in all people. In many cases,while taxing people’s coping mechanisms, no lasting damage is caused. While <strong>the</strong>experience may be accompanied by feelings <strong>of</strong> emoti<strong>on</strong>al discomfort, and may significantlyaffect well-being at <strong>the</strong> time, it does not necessarily lead to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> apsychological or physiological disorder 1 .In cases for example where exposure is prol<strong>on</strong>ged, health effects may result. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>health state itself may act as a stressor, as it may sensitise <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> to o<strong>the</strong>r sources <strong>of</strong> stressby reducing <strong>the</strong>ir ability to cope 2 . Within limits, <strong>the</strong> comm<strong>on</strong> assumpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> a relati<strong>on</strong>shipbetween <strong>the</strong> stressor, <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> stress and poor health appears justified 3 .The health effects <strong>of</strong> work stress are discussed under two headings:• physiological and physical effects; and• psychological and psychiatric.Physiological and physical effects <strong>of</strong> stressPhysiological process<strong>Work</strong> stressors or hazards or risks are defined as envir<strong>on</strong>mental situati<strong>on</strong>s or eventspotentially capable <strong>of</strong> producing <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> stress 4 . When exposed to a stressor, <strong>the</strong> body’sreacti<strong>on</strong> involves a number <strong>of</strong> physiological processes. It is generally agreed that <strong>the</strong>re aretwo arousal pathways in <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>se to stress 5 :• <strong>the</strong> hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-cortical arousal system (HPA axis) thatinvolves <strong>the</strong> activati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adrenal cortex by <strong>the</strong> pituitary gland to releasecortisol into <strong>the</strong> blood; and<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 11

• SNS-adrenal-medullary arousal involves stimulati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adrenal medulla,by <strong>the</strong> hypothalamus acting through sympa<strong>the</strong>tic nervous system (SNS) torelease adrenalin and SNS synapses to release noradrenalin.Stages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>se to stressWhen faced with a challenge (i.e. a stressor), complex interacti<strong>on</strong>s occur, with feedbackbetween <strong>the</strong> systems, but in due course <strong>the</strong>re is a return to baseline levels. The initialreacti<strong>on</strong> is adaptive and enables <strong>the</strong> individual to mobilise energy resources in <strong>the</strong> body todeal with <strong>the</strong> stressor. Comm<strong>on</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>ses are increased heart rate, increased blood pressure,more rapid breathing.When <strong>the</strong> exposure to <strong>the</strong> stressor is c<strong>on</strong>tinuous (chr<strong>on</strong>ic) or severe (e.g. violent act),however, health problems can occur. This is presumed to be because <strong>of</strong> sustainedphysiological arousal associated with <strong>the</strong> stressor.With repeated exposure to a stressor, <strong>the</strong> individual enters <strong>the</strong> stage <strong>of</strong> resistance wheredifferent physiological changes occur as <strong>the</strong> individual attempts to withstand <strong>the</strong> stressor.Finally if <strong>the</strong> stressor c<strong>on</strong>tinues a stage <strong>of</strong> exhausti<strong>on</strong> is reached where organic damage, oreven death can occur 6 .By progressing through <strong>the</strong>se stages, <strong>the</strong> normal physiological resp<strong>on</strong>se may turnpathological 7 .Chr<strong>on</strong>ic stressWhen an individual has been exposed to demands <strong>on</strong> a chr<strong>on</strong>ic basis with little opportunityfor c<strong>on</strong>trol, for example in high stress jobs, <strong>the</strong> resting baseline levels <strong>of</strong> both adrenalin andcortisol are raised. Am<strong>on</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r changes <strong>the</strong>re is also a slower return to baseline levels 8 . Thisindicates a diminished ability to cope physiologically 9 .It is assumed that chr<strong>on</strong>ic stress results in an inability to recharge <strong>the</strong> adrenomedullaryresp<strong>on</strong>se required for adaptati<strong>on</strong> 10 . This leads to adrenalin degenerati<strong>on</strong> 11 . Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>elevated levels <strong>of</strong> adrenalin and cortisol may affect cardiovascular health. This is thought tooccur partly via <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> horm<strong>on</strong>es <strong>on</strong> blood pressure and serum cholesterol levels 12 .There is growing evidence for <strong>the</strong> neuroendocrine-immunological mediati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong>psychosocial stressors <strong>on</strong> health and quality <strong>of</strong> life 13 , even <strong>the</strong> comm<strong>on</strong> cold 14 . The c<strong>on</strong>cept<strong>of</strong> allostatic load is relevant here 15 . Allostasis refers to <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>se <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> body required toreturn to homeostasis. Allostatic load refers to <strong>the</strong> inefficient operati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> allostatic systems,whereby activated horm<strong>on</strong>es are not ‘turned <strong>of</strong>f’ 16 . This c<strong>on</strong>cept is being used as anorganizing framework for examining a range <strong>of</strong> emoti<strong>on</strong>al, behavioural, and social factors inrelati<strong>on</strong> to a variety <strong>of</strong> health outcomes.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 12

Evidence <strong>of</strong> health outcomesThe clearest evidence for <strong>the</strong> health effects <strong>of</strong> work stressors comes from a number <strong>of</strong> studies,particularly those tests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> a key model <strong>of</strong> work stress: <strong>the</strong> jobdemand/c<strong>on</strong>trol model. This model, which will be discussed in detail later, sees work stressas arising from jobs where <strong>the</strong> worker has a high level <strong>of</strong> job demands in combinati<strong>on</strong> with alow level <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol (e.g. little latitude for decisi<strong>on</strong>-making).Research findings include:• elevated risk <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular disease related due to job strain (highdemand-low c<strong>on</strong>trol) has been dem<strong>on</strong>strated in a number <strong>of</strong> l<strong>on</strong>gitudinalstudies 17 ;• results from <strong>the</strong> Whitehall II study c<strong>on</strong>firm that people at lower levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>civil service have poorer health, fur<strong>the</strong>r reinforcing <strong>the</strong> well-established fact<strong>of</strong> a socio-ec<strong>on</strong>omic gradient in worker health 18 . Reas<strong>on</strong>s for this gradient arethought to include work stress;• <strong>the</strong> Whitehall II study also shows a link between low levels <strong>of</strong> job c<strong>on</strong>troland an increased risk <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary heart disease (eg. plasma fibrinogen) 19 ; and• an increase in obesity due to job strain 20 .CHD is also linked to working l<strong>on</strong>g hours 21 .Most c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s susceptible to work stress involve <strong>the</strong> cardiovascular and respiratorysystems, (eg CHD, and asthma), <strong>the</strong> immune system (eg rheumatoid arthritis), and <strong>the</strong> gastrointestinalsystem (eg gastric ulcers) 22 .Psychological and psychiatric outcomesChr<strong>on</strong>ic strainAno<strong>the</strong>r c<strong>on</strong>cept comm<strong>on</strong> to many stress models is that <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> stress leads to acutereacti<strong>on</strong>s, or symptoms <strong>of</strong> strain in <strong>the</strong> worker. These reacti<strong>on</strong>s may be transitory andnecessary to cope with a new challenge. However, <strong>the</strong> accumulati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> strains over time isc<strong>on</strong>sidered to result in psychological and behavioural effects as well as physiologicalreacti<strong>on</strong>s 23 .Cognitive and psychological effectsPsychological strain includes cognitive and psychological effects, such as:• an inability to c<strong>on</strong>centrate;• job dissatisfacti<strong>on</strong>;<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 13

• affective disorders, including anxiety, depressi<strong>on</strong> 24 and anger 25 ; and• somatic symptoms such as headaches, perspirati<strong>on</strong>, and dizziness 26 .Psychological c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s that are investigated as c<strong>on</strong>sequences <strong>of</strong> job stress may notnecessarily be classifiable under recognised psychiatric classificati<strong>on</strong> systems. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> may represent ‘significant functi<strong>on</strong>al disturbances or risks for <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong>clinical disorders’ 27 . L<strong>on</strong>ger term psychological outcomes may include mental illness andsuicide 28 . For example, <strong>the</strong> Whitehall II study found that social support at work, lowdecisi<strong>on</strong> latitude, high job demands, and effort-reward imbalance were associated withincreased risk <strong>of</strong> psychiatric disorder over time 29 .Behavioural strainThis may be indicated by increased or excessive use <strong>of</strong> alcohol and drugs, including tobacco;or by reduced work performance, higher levels <strong>of</strong> absenteeism or sick leave, industrialaccidents and staff turnover 30 .Besides <strong>the</strong>se outcomes, strain from <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment may spill over into <strong>the</strong> homeenvir<strong>on</strong>ment, leading to marital problems and o<strong>the</strong>r social issues 31 .Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)A range <strong>of</strong> traumatic stressors may be experienced in <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment as intense, acuteevents, bey<strong>on</strong>d <strong>the</strong> normal range <strong>of</strong> expectati<strong>on</strong>s; for example, <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> violentincidents, witnessing a robbery, working with abused clients, or dealing with road accidents.Such events may even be life threatening.The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual <strong>of</strong> Mental Disorders (DSM-IVTR 2000), and <strong>the</strong>Internati<strong>on</strong>al Classificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Diseases (ICD-10) provide <strong>the</strong> criteria for diagnosis <strong>of</strong> PTSD,including <strong>the</strong> exposure to a traumatic event, and <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> sequelae associated withthat event.Symptoms typically include:• intrusive recollecti<strong>on</strong>s;• dreams;• sensitivity to stimuli associated with <strong>the</strong> initial event; and• avoidance <strong>of</strong> activities or situati<strong>on</strong>s associated with <strong>the</strong> trauma.A range <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r psychological c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s may co-exist with PTSD, such as anxiety,depressi<strong>on</strong>, thoughts <strong>of</strong> suicide, panic disorder, anti-social pers<strong>on</strong>ality disorder, agoraphobia,and substance abuse 32 . Chr<strong>on</strong>ic stressors have also been viewed as a precursor to PTSD, forexample in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> bullying 33 . In c<strong>on</strong>trast to most o<strong>the</strong>r assessments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> workevents <strong>on</strong> workers, PTSD has a str<strong>on</strong>g legal positi<strong>on</strong>. This is because a distinctive feature <strong>of</strong><strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 14

<strong>the</strong> disorder is that it can be diagnosed clinically, while at <strong>the</strong> same time addressing <strong>the</strong> issue<strong>of</strong> causality 34 .The physiological changes thought to result from chr<strong>on</strong>ic stress, ie. chr<strong>on</strong>ic neuroendocrineand cardiovascular over-arousal, peripheral adrenalin degenerati<strong>on</strong> and cardiovasculardegenerati<strong>on</strong> 35 are presumed to underpin both psychological and physical health problems.MAJOR MODELS OF WORK STRESSThe c<strong>on</strong>text <strong>of</strong> stressThe literature <strong>on</strong> work stress reveals <strong>the</strong> influence <strong>of</strong> socio-political c<strong>on</strong>texts <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> researchagenda and <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> way work stress is c<strong>on</strong>ceptualised 36 . Of course, <strong>the</strong> discussi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> stress, orindeed anything else, does not arise in a political or ideological vacuum 37 .Early research <strong>on</strong> work stress (e.g. beginning with that <strong>of</strong> Kahn and his colleagues 38 andc<strong>on</strong>tinuing in <strong>the</strong> USA during <strong>the</strong> 1960s and ‘70s 39 ) focused <strong>on</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>al attributes andsubjective characteristics ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong>. It has been arguedthat this individualised c<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> role stress effectively depoliticised <strong>the</strong> discussi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>work stress, facilitating its easy passage into corporate human resource management 40 .At <strong>the</strong> same time in <strong>the</strong> Scandinavian countries, a social democratic political approach to <strong>the</strong>issue was emerging. The climate gave rise to a radically different research perspectivefocusing <strong>on</strong> work characteristics and occupati<strong>on</strong>al health. The c<strong>on</strong>text was <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> workreform and industrial democracy, and it was supported by trade uni<strong>on</strong>s, government andemployers’ organisati<strong>on</strong>s 41 .Since <strong>the</strong> early 1960s research in <strong>the</strong> area has burge<strong>on</strong>ed, leading to different understandingsabout what stress is or means. Since stress has many causes, investigators have been able t<strong>of</strong>ormulate, and at least partially validate, substantially different models <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> causes <strong>of</strong>stress 42 .Moreover, ideas <strong>of</strong> stress are fur<strong>the</strong>r complicated by <strong>the</strong> incorporati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> various values, suchas:• a humanistic-idealistic desire for a good society and working life;• a drive for health and well-being;• a belief in worker participati<strong>on</strong>, influence, and c<strong>on</strong>trol at <strong>the</strong> individuallevel; and• an ec<strong>on</strong>omic interest in competitiveness and pr<strong>of</strong>its <strong>of</strong> businessorganisati<strong>on</strong>s and <strong>the</strong> ec<strong>on</strong>omic system.Placed within this framework, occupati<strong>on</strong>al stress becomes a social and political problem asmuch as a health problem 43 .There is general agreement in <strong>the</strong> literature about <strong>the</strong> definiti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> a stressor (antecedent <strong>of</strong>stress) and a strain (c<strong>on</strong>sequence <strong>of</strong> stress). As we shall see, however, stress definiti<strong>on</strong>s vary<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 15

according to a <strong>the</strong>oretical perspective. Some <strong>the</strong>ories do not specifically define <strong>the</strong>intermediary term ‘stress’. <strong>Work</strong> stress, job stress and occupati<strong>on</strong>al stress are <strong>of</strong>ten usedinterchangeably. A generic definiti<strong>on</strong> given is “job stress can be defined as <strong>the</strong> harmfulphysical and emoti<strong>on</strong>al resp<strong>on</strong>ses that occur when <strong>the</strong> requirements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> job do not match<strong>the</strong> capabilities, resources, or needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> worker. Job stress can lead to poor health and eveninjury” 44 .<strong>Work</strong> stress <strong>the</strong>ories, paradigms, and frameworks<strong>Work</strong> stress <strong>the</strong>ories attempt to describe, explain and predict stress/strain according to acoherent set <strong>of</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>ses. The many <strong>the</strong>ories differ in emphasis, but <strong>the</strong>ir c<strong>on</strong>tent is <strong>of</strong>tenoverlapping and complementary. Tax<strong>on</strong>omies include <strong>the</strong> following:• stimulus/resp<strong>on</strong>se combinati<strong>on</strong>s 45 ;• sociological vs psychological paradigms; and• envir<strong>on</strong>mental vs individual emphasis.Cox et al (2000) assert that most current stress <strong>the</strong>orising is psychological, and c<strong>on</strong>ceptualiseswork stress in terms <strong>of</strong> a negative psychological state, and <strong>the</strong> dynamic interacti<strong>on</strong> between<strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong>ir work envir<strong>on</strong>ment. This includes:• interacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ories, focusing <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> structural features <strong>of</strong> a pers<strong>on</strong>’sinteracti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong>ir work envir<strong>on</strong>ment; and• transacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ories, focusing <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> cognitive processes and emoti<strong>on</strong>alreacti<strong>on</strong>s associated with <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>’s interacti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong>ir envir<strong>on</strong>ment 46 .In reality this framework is not clear–cut as some models clearly embrace importantsociological influences (ie DCS & ERI). Four dominant c<strong>on</strong>temporary <strong>the</strong>oretical models <strong>of</strong>work stress are discussed below.Interacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>oriesInteracti<strong>on</strong>al models explain work stress in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> individual’s interacti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong> workenvir<strong>on</strong>ment.Demand-c<strong>on</strong>trol/support modelThe job demand-c<strong>on</strong>trol (JDC, or DC) model put forward by Karasek argues that work stressarises primarily from <strong>the</strong> structural or organisati<strong>on</strong>al aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment ra<strong>the</strong>rthan from pers<strong>on</strong>al attributes or demographics 47 . According to this model, ‘strain results from<strong>the</strong> joint effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> demands <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work situati<strong>on</strong> (stressors) and envir<strong>on</strong>mentalmoderators <strong>of</strong> stress, particularly <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> decisi<strong>on</strong> making freedom (c<strong>on</strong>trol) available to<strong>the</strong> worker facing those demands’ 48 .<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 16

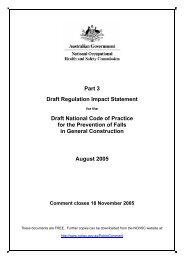

Strain is understood to result for people with objective high job demand and objective lowc<strong>on</strong>trol over <strong>the</strong>ir work, irrespective <strong>of</strong> individual differences in appraisal or coping 49 . Thisc<strong>on</strong>ceptualisati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> stress views envir<strong>on</strong>mental causes as <strong>the</strong> starting point, although it doesnot strictly preclude <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>al factors 50 .Objective stressor → StrainEmpirical tests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment model ideally investigate <strong>the</strong> link between objectivestressors and illness 51 . <strong>Stress</strong> in <strong>the</strong>se models refers to <strong>the</strong> intermediate state <strong>of</strong> arousalbetween <strong>the</strong> objective stressor and strain. Karasek notes that this state (stress) is rarelymeasured in his research 52 .Drawing from research in industrial sociology, animal research <strong>on</strong> ‘learned helplessness’ 53and health psychology, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory hypo<strong>the</strong>sises that when workers are faced with high levels<strong>of</strong> demands and a lack <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol over decisi<strong>on</strong> making and skill utilisati<strong>on</strong>, adverse heal<strong>the</strong>ffects will result:• as levels <strong>of</strong> psychological work demands increase and workplace aut<strong>on</strong>omyor c<strong>on</strong>trol decreases levels <strong>of</strong> psychological strain increase (follow Diag<strong>on</strong>alA, Figure 1) 54 ; and• as demands and c<strong>on</strong>trol increase c<strong>on</strong>gruently, increases in job satisfacti<strong>on</strong>,motivati<strong>on</strong>, learning, efficacy, mastery, challenge, and performance will beobserved (follow Diag<strong>on</strong>al B).Karasek argues that high demand jobs produce a state <strong>of</strong> normal arousal (i.e. increased heartrate, increased adrenalin, increased breathing rate), enabling <strong>the</strong> body to resp<strong>on</strong>d to <strong>the</strong>demand. However if <strong>the</strong>re is an envir<strong>on</strong>mental c<strong>on</strong>straint, such as low c<strong>on</strong>trol, <strong>the</strong> arousalcannot be channeled into an effective coping resp<strong>on</strong>se (e.g. participati<strong>on</strong> in social activitiesand informal rituals). Unresolved strain may in turn accumulate and as it builds up can resultin anxiety, depressi<strong>on</strong>, psychosomatic complaints and cardiovascular disease.According to <strong>the</strong> model, workers in high strain jobs (e.g. machine paced, assemblers, andservice-based cooks and waiters) experience <strong>the</strong> highest levels <strong>of</strong> stress. High status workers,such as executives and pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>als, have frequent opportunities to c<strong>on</strong>trol or regulate highlevels <strong>of</strong> demands (i.e. active jobs).<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 17

TimeΣ2Feeling <strong>of</strong>MasteryHIGHDecisi<strong>on</strong> LatitudeLOWPsychological DemandsLOWlow strainjobpassivejobactive jobActiveLearninghigh strainjobResidualStrainAccumulated Anxiety InhibitsLearning Attempts34Feeling <strong>of</strong> Mastery InhibitsStrain Percepti<strong>on</strong>HIGH B ATimeΣ1AccumulatedStrainFigure 1. The psychological demand-decisi<strong>on</strong> latitude model: Dynamicassociati<strong>on</strong>s linking envir<strong>on</strong>mental strain and learning to evoluti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>ality.Adapted with permissi<strong>on</strong> from Healthy <strong>Work</strong>: <strong>Stress</strong>, Productivity, and <strong>the</strong> Rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Work</strong>ing Life (p 99), by R. A. Karasek and T. Theorell, 1990, New York: Basic Books.The model has been expanded to include social support as an important aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> workenvir<strong>on</strong>ment 55 . A recent review <strong>of</strong> 81 studies <strong>of</strong> social support, in particular emoti<strong>on</strong>alsupport, found that it was reliably related to beneficial effects <strong>on</strong> aspects <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular,endocrine and immune systems 56 . Fur<strong>the</strong>r, potential pers<strong>on</strong>al health related behaviours didnot appear to be resp<strong>on</strong>sible for <strong>the</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s. Jobs with high demands, low c<strong>on</strong>trol, andlow support from supervisors or co-workers (DCS model) carry <strong>the</strong> highest risk forpsychological or physical disorders (high strain-isolated jobs).C<strong>on</strong>siderable empirical support for <strong>the</strong> model has been found:• empirical tests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> DC model have shown that large-scale multioccupati<strong>on</strong>alstudies tend to provide support for interacti<strong>on</strong> effects betweendemand and c<strong>on</strong>trol predicting strain 57 ;• smaller scale studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> DC model in homogeneous samples have foundprimarily main effects <strong>of</strong> demands and c<strong>on</strong>trol 58 ;<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 18

• epidemiological studies provide <strong>the</strong> most c<strong>on</strong>vincing support for <strong>the</strong> coreassumpti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> DCS model 59 . L<strong>on</strong>gitudinal studies have shown job strainto predict myocardial infarcti<strong>on</strong> (heart attack) in a study <strong>of</strong> working men overten years 60 ;• in a recent review <strong>of</strong> ten l<strong>on</strong>gitudinal studies <strong>of</strong> men, six showed an increasein cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk due to job strain (high demands, lowc<strong>on</strong>trol), and two showed mixed results. Of five cohort studies in women,four showed higher levels <strong>of</strong> elevated risk in CVD related to job strain 61 ; and• fur<strong>the</strong>r, a recent study <strong>of</strong> 33 698 working women (nurses) in <strong>the</strong> UnitedStates found high strain workers showed lower vitality and mental health,higher pain, and increased risk <strong>of</strong> both physical and emoti<strong>on</strong>al limitati<strong>on</strong>sthan workers in ‘active jobs’. Iso-strain (high strain-isolated) work increased<strong>the</strong> risks fur<strong>the</strong>r 62 .Most studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> DCS framework have examined <strong>the</strong> job strain hypo<strong>the</strong>sis, though‘patterns <strong>of</strong> active coping behaviour could affect <strong>the</strong> progressi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> disease development’ 63 .A South Australian study <strong>of</strong> 419 correcti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>of</strong>ficers 64 showed that <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> active copingwas significantly higher in active jobs than in passive jobs, c<strong>on</strong>sistent with <strong>the</strong> idea thatworkers experiencing passive jobs, with little opportunity for c<strong>on</strong>trol, will show reducedmotivati<strong>on</strong> to tackle new problems. A more recent study found both increased workermotivati<strong>on</strong> but also greater health impairment in 381 insurance company workers in activejobs 65 . It was argued that <strong>the</strong> levels <strong>of</strong> demands were in fact too high, that <strong>the</strong>y were notreduced by increasing c<strong>on</strong>trol, and that nei<strong>the</strong>r too few or too many demands are good foremployees 66 .Evaluati<strong>on</strong>In comparis<strong>on</strong> to all o<strong>the</strong>r models, empirical testing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> DC(S) models has dominated <strong>the</strong>occupati<strong>on</strong>al stress research in <strong>the</strong> past 15 years. This is probably in part due to <strong>the</strong> ease withwhich <strong>the</strong> highly specified three dimensi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> model can be researched. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rhand, <strong>the</strong> model has been criticised for its relative simplicity and predictably, its lack <strong>of</strong>attenti<strong>on</strong> to psychological processes.Although <strong>the</strong> model is essentially a sociological model, a challenge is that tests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> modelare usually by self-report and in this way results represent psychological appraisals ra<strong>the</strong>r thanassessments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> objective situati<strong>on</strong> 67 . There is, however, good evidence <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sistencybetween self-report and objective ratings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment 68 .The model attracts str<strong>on</strong>g empirical support and has good face value in <strong>the</strong> workplace 69 .However modern work demands are squeezing out “passive” and “relaxed” jobs (eg scientistsincreasingly compete for funding, physicians participate in settings <strong>of</strong> corporate managedcare), which may lead to two classes <strong>of</strong> occupati<strong>on</strong>s: those with high c<strong>on</strong>trol or those withlow c<strong>on</strong>trol, but all with high demands 70 .<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 19

The model helps to develop links between productivity and healthy work. It takes account <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> work envir<strong>on</strong>ment imperative <strong>of</strong> productivity and postulates that increased productivitywill occur when workers have jobs that combine high demands and high c<strong>on</strong>trol (i.e. activejobs).BurnoutThe noti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> burnout is particularly relevant for people-oriented pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>s. It is thought toresult from prol<strong>on</strong>ged exposure to chr<strong>on</strong>ic interpers<strong>on</strong>al stressors <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> job, especially fromworking with troubled people. Burnout is c<strong>on</strong>ceptualised as ‘an individual stress experienceembedded in a c<strong>on</strong>text <strong>of</strong> complex social relati<strong>on</strong>ships, and it involves <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>’sc<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> both self and o<strong>the</strong>rs’ 71 .Although human service work is argued to impose special stressors <strong>on</strong> workers because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>client’s emoti<strong>on</strong>al demands 72 , some studies have found that stressors such as client’semoti<strong>on</strong>al demands, or problems associated with <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>al helping role, such as failureto live up to <strong>on</strong>e’s own ideals, are less potent in predicting stress than those more in comm<strong>on</strong>with o<strong>the</strong>r n<strong>on</strong>-helping pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>s 73 . For example a US study <strong>of</strong> 168 protective servicespers<strong>on</strong>nel (social workers) found that organisati<strong>on</strong>al variables were more str<strong>on</strong>gly associatedwith job satisfacti<strong>on</strong> and burnout than were client factors 74 .Overall empirical research <strong>on</strong> burnout has generally shown that job factors are more str<strong>on</strong>glyrelated to burnout than are biographical or pers<strong>on</strong>al factors 75 . The burnout process is said tobegin with some frustrati<strong>on</strong> or loss <strong>of</strong> aut<strong>on</strong>omy with which <strong>the</strong> individual failed to copeadequately 76 .Maslach and Jacks<strong>on</strong> note that although pers<strong>on</strong>ality variables are certainly important inburnout, research has led us to <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> that <strong>the</strong> problem is best understood (andmodified) in terms <strong>of</strong> job-related stress 77 . The prevalence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> phenomen<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> range<strong>of</strong> seemingly disparate pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>als who are affected by it suggest that <strong>the</strong> search for causesis best directed towards uncovering <strong>the</strong> operati<strong>on</strong>al and structural characteristics <strong>of</strong> stressfulsituati<strong>on</strong>s.Recent <strong>the</strong>oretical developments regarding burnout have turned to more positivec<strong>on</strong>ceptualisati<strong>on</strong>s, focusing <strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trasting or opposite states <strong>of</strong> burnout - specificallyengagement 78 . Engagement c<strong>on</strong>sists <strong>of</strong> high energy (ra<strong>the</strong>r than exhausti<strong>on</strong>), str<strong>on</strong>ginvolvement (ra<strong>the</strong>r than cynicism), and a sense <strong>of</strong> efficacy 79 .One c<strong>on</strong>cept <strong>of</strong> interest to researchers is <strong>the</strong> job-pers<strong>on</strong> fit model, not in <strong>the</strong> narrow sense <strong>of</strong>how an individual pers<strong>on</strong>ality fits with <strong>the</strong> job, but ra<strong>the</strong>r how <strong>the</strong>ir motivati<strong>on</strong>s, emoti<strong>on</strong>s,values and job expectati<strong>on</strong>s fit with <strong>the</strong> job, or <strong>the</strong> organisati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>text.Job-pers<strong>on</strong> mismatch is hypo<strong>the</strong>sised to lead to burnout: <strong>the</strong> greater <strong>the</strong> mismatch <strong>the</strong> greater<strong>the</strong> burnout. Maslach and Leiter 80 outline six areas where mismatch can occur, resulting inincreased exhausti<strong>on</strong>, cynicism, and inefficacy:• work overload occurs when <strong>the</strong> job demands exceed limits;<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 20

• lack <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol occurs when people have little c<strong>on</strong>trol over <strong>the</strong> work <strong>the</strong>y do,ei<strong>the</strong>r because <strong>of</strong> rigid policies and tight m<strong>on</strong>itoring, or because <strong>of</strong> chaoticjob c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s;• insufficient reward involves a lack <strong>of</strong> appropriate rewards for <strong>the</strong> work;• breakdown <strong>of</strong> community occurs when people lose a sense <strong>of</strong> positivec<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> with o<strong>the</strong>rs in <strong>the</strong> workplace, <strong>of</strong>ten due to c<strong>on</strong>flict;• absence <strong>of</strong> fairness occurs with <strong>the</strong> perceived lack <strong>of</strong> a just system and fairprocedures which maintain mutual respect in <strong>the</strong> workplace; andEvaluati<strong>on</strong>• value c<strong>on</strong>flict occurs when <strong>the</strong>re is a mismatch between <strong>the</strong> requirements <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> job and peoples’ principles.According to Maslach (1998), <strong>the</strong> six mismatch model may be useful when formulatinginterventi<strong>on</strong>s. It has been argued 81 that burnout research may be flawed as it merely reframesor renames a phenomen<strong>on</strong> that o<strong>the</strong>r occupati<strong>on</strong>al groups share.The framework focuses attenti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ship between <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong>,ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>e or <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r in isolati<strong>on</strong>. Research tends to find job factors more str<strong>on</strong>glylinked to burnout than pers<strong>on</strong>al factors. The model identifies key work dimensi<strong>on</strong>s whichoverlap with <strong>the</strong> DCS and ERI models.Transacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>oriesEffort-reward imbalance model (ERI)Like o<strong>the</strong>r transacti<strong>on</strong>al <strong>the</strong>ories <strong>of</strong> stress, this model 82 focuses <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> cognitive processes andemoti<strong>on</strong>al reacti<strong>on</strong>s associated with <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>’s interacti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong>ir envir<strong>on</strong>ment. That is, itemphasises <strong>the</strong> interacti<strong>on</strong> between envir<strong>on</strong>mental c<strong>on</strong>straints or threats, and individualcoping resources. It also relates to <strong>the</strong> social framework <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> job (e.g. social status <strong>of</strong> job(see Figure 2).According to this model, workers expend effort at work and <strong>the</strong>y expect rewards as part <strong>of</strong> asocially (negotiated) organised exchange process <strong>of</strong> work. It assumes that <strong>the</strong> work role inadult life provides a crucial link between self-regulatory functi<strong>on</strong>s such as self-esteem andself-efficacy and <strong>the</strong> social opportunity structure. ERI <strong>the</strong>ory emphasises rewards (such asm<strong>on</strong>ey, esteem, and social c<strong>on</strong>trol) ra<strong>the</strong>r than job c<strong>on</strong>trol. Strain results when an imbalanceoccurs between <strong>the</strong> efforts a worker puts in, and <strong>the</strong> rewards that are received. For example,workers who have high job demands and low pay, or who experience a threat to <strong>the</strong>ir jobsecurity or status, are likely to experience strain as a result <strong>of</strong> this imbalance. This can beexpressed in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ratio <strong>of</strong> efforts/reward.<strong>Work</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> Theory and Interventi<strong>on</strong>s: From Evidence to Policy by Assoc. Pr<strong>of</strong>. Maureen Dollard, PhD, University <strong>of</strong> SouthAustralia. <str<strong>on</strong>g>N<strong>OHS</strong>C</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Symposium</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>OHS</strong> Implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> 21