View PDF - Philadelphia Folklore Project

View PDF - Philadelphia Folklore Project

View PDF - Philadelphia Folklore Project

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

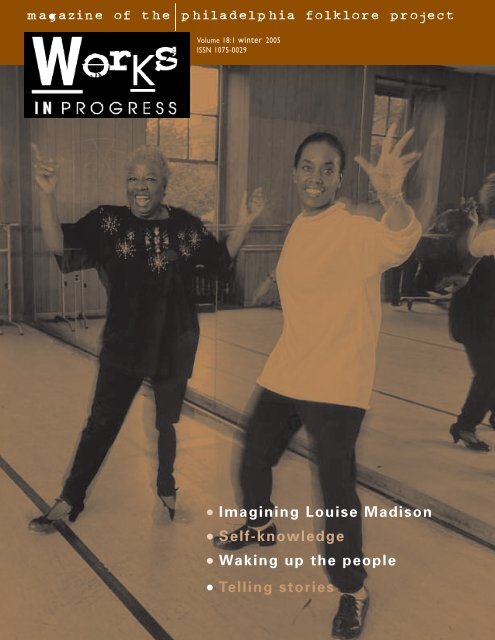

magazine of thephiladelphia folklore projectVolume 18:1 winter 2005ISSN 1075-0029● Imagining Louise Madison● Self-knowledge● Waking up the people● Telling stories

Works in progress is the magazine ofthe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>,an 18-year-old public interest folklifeorganization.We work with people andcommunities in the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> area tobuild critical folk cultural knowledge,sustain the complex folk and traditionalarts of our region,and challengepractices that diminish these local grassrootsarts and humanities.To learn more,please visit us:www.folkloreproject.org or call215.468.7871philadelphia folkloreproject staffEditor/PFP Director: Debora KodishAssociate Director: Toni Shapiro-Phim,Designer: IFE designs + AssociatesPrinting: Garrison Printers[ Printed on recycled paper]inside3 From the editor4 Imagining Louise MadisonBy Germaine Ingram8 Self KnowledgeBy Kathryn L. Morganphiladelphia folkloreproject boardGermaine IngramMogauwane MahloeleIfe Nii-OwooEllen SomekawaDeborah WeiDorothy WilkieMary YeeJuan Xuwe gratefully acknowledgesupport from:●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●The National Endowment for the Arts, whichbelieves that a great nation deservesgreat artsThe William Penn FoundationThe Pew Charitable TrustsPennsylvania Council on the ArtsPennsylvania Historical and MuseumCommissionIndependence FoundationThe Malka and Jacob Goldfarb FoundationThe Humanities-in-the Arts Initiative,administered by The PennsylvaniaHumanities Council, and funded principallyby the Pennsylvania Council on the ArtsDance Advance, a grant program fundedby The Pew Charitable Trusts andadministered by Drexel University<strong>Philadelphia</strong> Exhibitions Initiative, a grantprogram funded by The Pew CharitableTrusts and administered by the Universityof the ArtsThe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Cultural FundThe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> FoundationStockton Rush Bartol FoundationThe Henrietta Tower Wurts Foundationand wonderful individual <strong>Philadelphia</strong><strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong> membersthank you to allFront cover:Edith “BabyEdwards” Huntand GermaineIngram, 1993.Photo: JaneLevine12 Waking up the peopleBy Linda Goss16 I’ve been telling storiesall my lifeBy Thelma Shelton Robinson24 Membership form

from theeditorAs the first black womanhired in many workplaces,the lawyer and writer PatriciaWilliams has often had causeto challenge bias. Sheobserves that her actionshave earned her a reputationas someone with remarkableinsight and as a radical troublemaker.But she sees herperspectives as far fromunique: people who find hersurprising are simply hearing,for the first time, some ofthe everyday insights andcommon experiences ofwhole classes of people justlike her, but generally excludedfrom—and unable tospeak and be heard in—thecontexts of universities andlaw firms. 1Speaking common experiencesout loud and in unusualcontexts can be a dangerous,lonely, and revolutionaryundertaking—especiallywhen such storytellingrepresents the perspectivesof people who are disenfranchisedand when it challengeseveryday practice. Inthis issue of Works inProgress, four AfricanAmerican women describeways that stories can shakethings up, challenge thestatus quo, and keep possibilitiesalive. They also considersome of the obstaclesfacing anyone following anoral tradition.It is 40 years sinceKathryn L. Morgan first wrotepublicly about her family’sstories, handed-down talesof resistance and oppositionto racism that had sustainedgenerations. Insisting on theimportance of AfricanAmerican middle classtraditions, family folklore, andwomen’s storytelling, Dr.Morgan challenged a widerange of scholarly and popularconventions. The firstAfrican American woman toget a Ph.D in <strong>Folklore</strong> fromthe University ofPennsylvania, she hasinspired many people, includingstoryteller Linda Goss,who grew up with a heritageof family tales in Alcoa,Tennessee. In the 1970s,Ms. Goss was in the vanguardof what would becomea storytelling movement, andher account in these pagesof her years at HowardUniversity give a glimpse ofwhat it felt like to balanceher attachments both to alegacy of Southern rural oraltradition and to the emergingBlack Arts and Black Powermovements.Who has the right to callherself a storyteller, a poet, adancer? Thelma SheltonRobinson describes howother people were consideredthe poets when shewas young, and how sheeventually came to claim theright to define herself. Ittakes courage to name yourselfin terms that feel right,that allow dignity, agency,and justice. But telling storiesis about more than self-definition.All the women in thismagazine see stories andstorytelling as a responsibility.As Kathryn Morgan saysabout her own storytellingmother: we pass on thingsthat ought to be known. Wepass on essential stories,stories that are necessary.Stories about AfricanAmerican tapper LouiseMadison are just such essentialstories for GermaineIngram. Madison had areputation as a great dancer,a solo act, a woman whowas anyone’s equal. Thesestories serve as an inspiration,and a point of beginningfor Ingram’s own dancing,and for her exploration of thehidden and all-but-forgottenhistories of earlier AfricanAmerican women tapdancers. And notably, whenthere is too large a gap in therecord, when stories areunknowable, Ingram (andMorgan) refuse to be daunted,turning to imagination,fiction, and art-making,grounded in what they doknow, but naming too thetragedies of what is lost.This spring, PFP will bringall of these people to variousstages, and we hope you’llbe there. Ingram’s essaymarks the long-delayedrelease of our documentary,Plenty of Good WomenDancers, about some ofthese amazing local AfricanAmerican women hoofers.Plenty will be broadcast onMarch 28th on WHYY, after a10-year effort by PFP (itself astory). Germaine is performingher own work on May22nd, as part of PFP’s artists inresidence program. Morgan,Goss and Robinson speak aspart of a PFP program onself-knowledge and storytellingon February 19th,organized as part of ArtSanctuary’s Celebration ofBlack Writing and in honor ofODUNDE’s 30th anniversary.And Goss leads a 3-sessionround-table storytelling programin the new home thatPFP is currently rehabbing. (Agreat chance to share yourown stories.) There is muchmore to tell than we can fitin these pages, and we inviteyou to check out the calendarof PFP programs on page23, to visit our website, orcall us for more information:www.folkloreproject.org,215.468.7871. We look forwardto seeing you. …— Debora Kodish1Patricia Williams, The Rooster’sEgg. Cambridge: HarvardUniversity Press, 1995, p. 93.3

point of view

ImaginingLouise Madison:remembering African American women dancersby GermaineIngramSome might judge it arather unprepossessingcelebration—a modest spreadof bagels, cream cheese andcoffee in the <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>’scramped but welcoming officeon a crisp weekend morningin November 2004. No festiveattire— just well-wornSaturday-run-the-errands duds,caps covering unprimped hair.People coming and going intwos and threes, sharing hugsand news of relocations,retirements, travels and otherpersonal tidbits. Friendspeering into old photographsexhibited on the walls,stitching an impromptupatchwork of memories ofLibby, Dee, Baby, Fambro,Hank, Mike, Dave, andTommy—all of whom havetransitioned since those headymonths in the fall and winterof 1993-94 when our livesseemed to revolve around themercurial course of “Steppingin Time,” PFP’s uncommonlydemocratic and elastic stageproduction that played tothree SRO houses at the ArtsBank at Broad and South inFebruary 1994.“Stepping” was a revuereminiscent of the stage showsof the 1930s, 40s and 50swhere African Americanperformers—dancers, singers,comics, variety acts andinstrumentalists—regaledaudiences of all ages. Our“Stepping” production was aplatform for a dozen or sosenior <strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns, most ofthem in their 60s and 70s(supported by about an equalnumber of younger folks,ranging from teenagers tobaby boomers), to relive thediscipline, excitement andcomradeship of producing ashow like the ones back in theday. On that brisk Saturdaymorning in November 2004,survivors of the show cametogether to celebrate thepublic release—after a decadeof wrangling with studios forthe rights to screen somearchival footage— of “Plenty ofGood Women Dancers,” a PFPdocumentary that recounts thejourney that “Stepping” tookfrom spontaneous conceptionin Isabelle Fambro’s basementone Sunday afternoon tofeathered and sequinedsplendor on an Avenue of theArts stage. Laced through thestory of the stage productionis a tribute to four AfricanAmerican women hooferswhose contribution to[Continued on next page ➝] 5

imagining louise madison/continued from p. 5Hortense Allen Jordanconfers with musiciansduring rehearsal for“Stepping in Time.”January 1994. Photo:Thomas B. MortonT<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s artistic and culturallegacy has been mostly overlooked.The women who are featured inthe documentary are as differentfrom one another as chocolates in aWhitman’s Sampler box. Edith “BabyEdwards” Hunt was a child star in<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s African Americancommunity from the time she wasfour years old, enthrallingDepression-era audiences with hersinging, tap dancing and acrobatics.(She was especially known for herChinese splits). She matured into apopular professional entertainer,half of the boy-girl song and danceteam of Spic and Span. At the timeof “Stepping,” Baby—well into her70s and recovering from a heartattack—brought the house downwith a bold and vibrantperformance, in marked contrast toher quiet and demure privatepersona.Libby Spencer hailed from New6York City, where as a youngster shepicked up tap steps and routinesfrom relatives and neighbors. In1940, eager for work, she auditionedand was hired for the famous ApolloTheater chorus line.As one of the“tall girls”on the line, she learnedthree new routines for each show,which typically changed weekly,and performed several shows perday. One of the highlights of hercareer was being paired inperformance on Broadway with BillBojangles Robinson.After marriagesettled her in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, MissLibby became a respected andbeloved jazz and tap dance teacherfor children and adults throughoutthe city.Even as a schoolgirl in her nativecity of St. Louis, Missouri, HortenseAllen Jordan forecasted the prolificdancer, choreographer, andproducer she would become. Shemined every opportunity to honeher talents in choreography andstagecraft, eventually assuming keycreative roles in the companies ofband leaders and producers such asLeonard Reed (creator of the “ShimSham Shimmy,” a/k/a “The TapDancers’ National Anthem”), LouisJordan, and Larry Steele. Sheconfronted barriers with doggedresourcefulness, as when sheresolved to design and fabricatecostumes for dancers in her choruslines rather than settle for the oldtattered goods that costume rentalhouses offered black productioncompanies.After settling down in<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, Hortense continued toproduce shows at the Robin HoodDell, Club Harlem in Atlantic City,and other local nightspots. (Jordanis the only one of Plenty’s foursubjects who survives.)<strong>Philadelphia</strong> native DoloresMcHarris married into hoofing. Shetrained intensively with her

husband, tap dancer and all-aroundshowman Dave McHarris, to prepareto share his life of entertainmentand international travel. Later, shebecame a capable drummer, oftenjoining her husband in a showstoppingdouble-drum set routine.McHarris and Dolores toured theirtroupe for many years beforesettling into semi-retirement in the<strong>Philadelphia</strong> area.Each of Plenty’s subjects gives usa distinct window into the roles thatAfrican American women haveplayed in shaping and promotingjazz tap dance, a dance form that iscentral to <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s culturallegacy and America’s contribution tothe world reservoir of dancetraditions: Baby Edwards for hersingular performance prowess;Libby Spencer for her historical andpolitical clarity; Hortense AllenJordan for her multiple talents andentrepreneurial spirit; and DeeMcHarris for her longevity andversatility.The video portrayal isenhanced by archival footage ofother women hoofers who defiedthe convention of tap as a men’sclub, among them the sensationalLois Miller of the <strong>Philadelphia</strong>-basedtap trio The Miller Brothers and Lois,a class act that merged catchyrhythms, sophisticated movementsand costuming, and excitingacrobatics. One woman who wouldcertainly have been represented inPlenty, had there been material todraw from, was Louise Madison, adancer little-known to today’s tapfans, and, as far as we know,undocumented on film or video. Shewas nonetheless remembered andgreatly admired by the veteranmembers of Stepping’s cast. Buteven without the aid of her wordsor performance exemplars, Louise,as remembered and imagined,provided a palpable backdrop forthe story that Plenty tells.It was around 1980 when I firstheard of Louise Madison from mymentor and dance partner, LaVaughnRobinson (now 78), who related hismemorable introduction to her.AsLaVaughn tells it, he was about 17years old when he and somebuddies were buskin’ (dancing onthe street for money) around<strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s South Street.Theywere approached by a local tapdancer known as “Cy” (of an actcalled Popcorn, Peanuts and CrackerJacks), who invited them to ride toNew Jersey to see an exceptionalhoofer, without disclosing that thedancer was a woman.The boysjumped into Cy’s run-down auto andmade the short trip to the CottonClub, a nightspot located in thehistoric African Americancommunity of Lawnside, New[Continued on p. 18➝]7

point of view

through me.I struggled. I strangled.I saw the myriad waters vibratelike a rainbow of flashing clawsjoining in the suffocating wetnesspenetrating, possessing, devouringbeast flinging me witha roar within, without.I was gone. 4My work with my family stories, slave narratives,ex-slave narratives, oral and written history, literatureabout black folk, and first hand experience with the terrorand violence of the racial status quo in the UnitedStates helped me to shape the following fictional conversationwith my ancestor, Caroline Gordon ofLynchburg, Virginia, affectionately called Caddy. If shecould speak to me about her life what would she say?How would she describe her contemporaries, thosetrapped in the terror of the slave labor system? Whatdoes this have to do with self-knowledge? I called thepiece “The Sage”:“Weep not for me because I am deadand you knew me not. Remember only that Ilived long enough to discover that I was notone but many. If you attach yourself only tomy suffering, I become nothing but the residueof oppression. Remember, I lived long enoughto discover that I was part of a hurricane, partof the twirl of lust, passion, joy, sorrow, cruelty,kindness, hate, love, laughter, birth anddeath that make up human existence. I knewwind, rain, water, fire and clouds. I discoveredthe beauty and ruthlessness in nature.Weep not for me because I am dead...Remember, I lived long enough to discover myown internal contradictions. I discovered myown strengths, weaknesses, lies, truths, falseness,and sincerity. I experienced the constancyof internal change within me. So I was bothhero and coward, conqueror and conquered,king and subject, owner and slave. Negativeand positive like everything else, everywhere.So you see, if you put my suffering above allelse, you stress only one part of me, only onepart of the whole. If you glorify my beauty, thenyou deny my ugliness. If you thus simplify myexistence, you desecrate my complexity.Weep not, for you have neither time norenergy…to waste. Remember you are at war. Awar started long ago. But do not abandon emotion.For life is empty devoid of emotion. But inwar, emotion must be backed up with intellect,power, discipline.Tears, curses, passivity and escapism neverwon battles, fed the hungry, clothed the naked,housed the homeless, weakened the enemy,or…cut through chains.” 5The life patterns, beliefs and customs traditionallyvalued by the storytellers in my family include:Remember the horrors of slavery. Never forget it.Cherish freedom. Listen to the wind for the whisper ofthe ancestor’s song. Listen with your heart and you willhear it. Weep not, we are at war. A war started long ago.What does all this say? Fantasy can be used toreflect the outcomes of self-knowledge. However, it canbe used to revitalize history, not to replace it. It can beused as one instrument in the mass of weaponry neededin the struggle for black liberation from racism andinjustice in the United States. It functions to free theimage of black folk behind the famous from their burialin a sea of undifferentiation. It functions to stir up the“mass” and capture the kaleidoscopic sense of complexityand diversity reflected in African American experiencesin the United States. It makes no pretense of conformitynor omnipotence. It values difference and doesnot deem it a hindrance to ultimate unity. It createsrather than documents and is based firmly upon theconviction that as much can be learned about selfknowledgefrom fiction as from fact.Dr. Kathryn L. Morgan is Sara Laurence Lightfoot EmeritaProfessor of History and Senior Research Scholar atSwarthmore College. Formerly on the board of the<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, she is part of this year’s LocalKnowledge project (p. 17). For more information about Dr.Morgan, visit the PFP website (www.folkloreproject.org.)Notes1The Community of Self. Jersey City, New Jersey: MindProduction, 1985. p. 312Some of these stories are recounted in Kathryn L. Morgan,Children of Strangers: The Stories of a Black Family.<strong>Philadelphia</strong>: Temple University Press, 19803Adapted from Kathryn Morgan, “More Excerpts from theMidnight Sun,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 5:1 (1977), pp. 86,88.4Adapted from Kathryn Morgan,“More excerpts from theMidnight Sun,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 5:1 (1977), p. 89.5Ibid “On black images and blackness,” Black World(December 1973), pp. 84-85.9

y Linda Gossartist*profile10

Photos this page: LindaGoss and her mother,Alcoa, Tennessee, c.1990s. Linda and hercousin Carolyn Crabtree,c. 1960s. Photoscourtesy Linda Goss.Facing page: LindaGoss, 2004. Photo:Debora KodishWaking upthe peopleWell, I guess I’ve alwaysbeen fascinated withlistening to stories.And I used to just listen to myaunts and uncles and youknow, my grandfather, and—Ihave an uncle who is livingnow, Uncle Buster. And he issuch a character. He is funny!And he is always telling stories.And he is really, like an oral historian.And it hasn’t been untilrecently that we even think ofhim as an historian, but that’swhat he is. That’s what he is.He’s in his 80s and people willcome to him and they’ll justcall out a name. They may say,“The Dean family” and he takesyou all the way back. Really,like the griots, back in Africa.You know. So whenever hesees me now, he just hugs meand we’ll get to talking aboutdifferent things. And he reallykind of inspires me.When I was younger, I wasinfluenced by my grandfather.You know, by granddaddyMurphy, and my parents. AndUncle Buster, I would hear abouthim. He was always the one whowould call on the phone and hewould call collect, you know, tomy mom. He would call with adifferent name. He would say,“It’s James calling.” And hewould trick her. Because if sheknew it was Buster, she wouldn’taccept the call. So he would say,“It’s Tyler on the phone.” Or “It’sLyle on the phone.” And he hasall of these names. His name isJames Lyle Tyler Martin. And he’sknown as Buster. So wheneverhe would call, it was always astory, just behind him. And atthe same time, as funny as he is,there’s also a sadness about him.And it wasn’t until as I got olderthat I discovered what thatsadness was.Because, it’s almost likepeople let Uncle Buster behimself. And come to find out,he was in World War Two. I thinkhe was stationed in Alaska orsomewhere. And my grandmotherpassed away. And for somereason, when he got the wordabout it, by the time he got backto Tennessee, everything wasover. Her funeral and everything.And he never—well, to this day,he has never gotten over it. Soeven when he starts telling stories,he’ll start laughing. And hemay start out on a very highnote. He may end just sobbingand crying, telling you about mygrandmother, telling you aboutsome of the sad things that havehappened in the town too.So from him, I guess, Ideveloped just the whole idea ofjust how powerful a story canbe. How it can just lift you upand at the same time, it can kindof purge you. It can kind of healyou. And even to this day, I kindof lean on Uncle Buster when Isee him. I kind of lean on himfor a little strength to just keepme going, and making me realizethat you do have to pull outsome of those stories that cankind of heal you, and some ofthose stories that are painful.But it’s important to get themout. It’s important to expressyourself. And I guess I’m thinkingabout him even more rightnow, because we are in a war situation.And that’s how my storytellingis. Depending on what’sgoing on in the world, dependingon what’s going on in mylife, what’s going on in my fami-[Continued on p. 14➝]11

artist*profileTelling storiesmy whole lifeThelma Shelton Robinson primarilyfocuses her tales on her own life experiences, and sharesstories that she heard coming up in <strong>Philadelphia</strong> in the1940s-1950s in a richly oral tradition. Her father was a vividstoryteller and her mother raised her on stories about herown childhood in Virginia. A weekend roomer, Mrs. Walton,told "stories… so scary you were afraid to go to bed." Herfather's corner store, Veteran's Rest, was a hangout for Ms.Robinson as a child; she'd go in and out, listening to neighborspassing time and telling tales. She valued what sheheard, appreciating the different narrative styles and perspectives.She reflects, "When an elder passes, it's like alibrary burns down because there is so much informationthat is lost. And without other people who know that information—itjust goes." Growing up near 12th and SouthStreets in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, around the corner from theStandard Theater, Ms. Robinson watched street cornersinging, dancing, and preaching, all of which left a lastingimpression. She also loved the rhyming poetry of PaulLaurence Dunbar and Langston Hughes, and she lovedmusic—from the Wings Over Jordan Choir to Louis Jordanand his Tympany 5. But it wasn't until she retired fromdecades of secretarial work that she began to truly pursueher love of poetry and storytelling. Over the last decades,she has made her presence felt, performing in storytellingcelebrations, schools, and other social, civil and educationalgatherings. She has received a PCA Fellowship in Folkand Traditional Arts and was awarded the Oshun award in2003, from ODUNDE, Inc., naming her the "poet laureate ofSouth <strong>Philadelphia</strong>." Here she reflects on how she becamea poet and storyteller.12

y ThelmaShelton RobinsonFamily photos: Thelma’sfather, “Hop Dick” Shelton,and Thelma, courtesy of theartist. Facing page: ThelmaShelton Robinson 2004,photo : Debora Kodish.Painting, “Yo Mama”courtesy Ife Nii-Owoo.Ifind that truth is strangerthan fiction. If you tell someof these true stories, peopledon't believe it. I tell aboutthings that I remembered as achild, and about things that wereimportant, not just to me, but toeverybody. Experience doesn'tmatter if you haven't got stories.I always loved stories. And Iloved to listen to stories in theneighborhood. My father was awalking storybook. See, he was ahustler. He did so many things. Heused to tell me back in Norfolk, hewould sell fish. And he used tohave a cart, and he’d say, “MissAnnie. Get your pots and pans,here I am the FISH man!” Healways had something that wouldrhyme. He would make things up,like: “To see how sweet your homecan be, go away but keep the key.”He’d say things like that all thetime. My father, he had charm.People loved to talk to him. And heloved talking! He had so many stories.After he came to <strong>Philadelphia</strong>,he sold vegetables. He sold papers.Then he had this little store on thecorner of Twelfth and Rodman. Andhe named it the Veteran’s Rest. Andhe had mainly men coming inthere. You know, that corner storewhere they shoot the bull. Theyplayed cards and they playedcheckers. And they’d argue. Andthey’d talk about their war experiencesand everything.We lived at 506 South SartainStreet, which was right across thestreet from the Standard Theateron South Street. And that was themain thoroughfare. I mean—therewere so many things you could see.They had people on the cornerpreaching, or tap-dancing, or whatnot.That was commonplace. I’dwatch things—because, you know,the different things you see- theactions that people put on. Whatyou would see happening in theneighborhood, well, the truth isstranger than fiction.I put myself in school. Becausemy brother and my sisters wereolder than I was. I was theyoungest. One morning I woke upand none of them were there. Thatwas odd. And when I asked mymother where they were, she said,“They went to school.” So at thattime, people would put their childrenout—they could go outsideand play and not worry what wasgoing to happen too much. So Iwent out to play and nobody wasout. And every house I went to onour side of the street, everytime Irang the bell or knocked on thedoor, I would ask for the child andthe mother would tell me, “They’rein school.”Nobody was outside but me.And I said, “School? I want to go toschool, too!”So I knew it was taboo to crossthe street. But I wanted to go toschool. So I looked, and I went andI crossed that street. Then I sawthis old friend of the family. Hisname was Mr. Whitey. He was aplumber. And he called me MommyLump. He says to me, “Where yougoing, Mommy Lump?” I said, “I’mgoing to school. But I need a bookand a pencil and piece of applepie.” (Always worried about mystomach! ) So he laughed and hetook me to the corner store, Mr.Snyderman’s little store, and I gotthe book and I got the pencils.Then we went next door. I thinkthere was a Greek restaurant thereand I got a piece of French applepie with the ice cream on the topand the raisins in it. So I was all set!So he was laughing! It tickled him.He just walked me on. He said,“Are you really going to school?”I always loved stories. And I loved tolisten to stories in the neighborhood.My father was a walkingstorybook.I said, “Yes.”So we went around onLombard Street and down to theschool entrance. And he stood atthe gate and he says, “OK, I’ll seeyou.” And I says, “OK.” And he juststood there and he was just laughing,and this lady happened tocome up and she had a little girlshe was going to enroll, so I wentin with them. And when I gotinside, there was a nun there. Andthe lady was giving her the informa-[Continued on p. 16➝]13

waking up the people /continued from p. 1114ly, kind of steers me into a way ofhow my stories come across.So the things that I know of mygrandmothers are stories that havebeen passed on to me from myfather and my mother. And what Inoticed that happens within theblack family is that there are storiesthat we share to the public, thereare stories we share with the world,but then there are very personalstories—I think Zora Neale Hurstontalked about that—that we justkeep inside, that we don’t sharewith anyone, that we don’t shareeven share within our families.And once I started sharing withpeople that I was a storyteller, that’swhen the family members startedcoming to me, sharing with me someof these stories, some of the stories Ihad never heard before.And it could have been becauseof my age, because I was a child.But I was always listening out. I wasone of these kids always eavesdropping,always finding out about stuff.I would pretend like I was on thecouch asleep but I’d be really eavesdropping.You know what I’m saying.So that’s how I found outabout a lot of stuff.But now, now that I’ve gottenolder and I’m supposedly the socalledstoryteller, now people cometo me with other stories. …I was always curious and Icould read at a very young ageaccording to my parents. Ofcourse everybody kind of exaggerates.Everybody’s a storyteller inmy family! They claimed I wasreading when I was two or three.But I became very ill. I had pneumoniaor chicken pox at the sametime and then I forgot everything.I became so sick they thought Iwas going to die. And that’s astory in itself. But when I cameout of that my mother startedreading to me again and tellingme stories. And they tell me how Iwould carry around a wagon. Iwould pull it. And inside were allthese books, my favorite books.Now I have a vague recollection,but that’s because they had toldme that, over and over again.But I just loved stories. I lovedlistening to stories on the radio, too.My favorite story at the time,when I was little, was Peter Rabbit.But I didn’t realize until as I gotolder, once my mom got sick, thatthat was her favorite story. So shewould tell me the story of PeterRabbit all the time. So I just lovedhearing about him. My father andmy grandfather would tell mestories of Buh Rabbit, and I wouldkind of mix the two together, youknow. My mother, really, was veryreligious and she would tell me lotsof Bible stories. And the way theywould tell me these stories—itwould just frighten me. It wouldjust scare me, you know.I didn’t start calling myself astoryteller really until 1973. Beforethat. I was in theater. Before that Iwas a poet. I was a writer. I alwayswanted to be writer. I think Iannounced I was going to be awriter when I was about 8 or 9years old.My mother encouraged me nomatter what I wanted to do. If I saidI was going to be a poet, my motherand father said, “Right on.” Iremember when I said I was goingto be a track runner. “Right on.” Nomatter what I said. I even said, onetime, I wanted to be a humanitarian.I didn’t even know what thatwas—they said “Right on.” I wantedto be an interpreter. I got hung upwith the United Nations. . . andbecause I was from a little town, Iwas influenced by television. Iwould have all these crazy ideas.Then the people in the town wouldgive you ideas, too. They would say,“Oh, the way you walk, Linda, Ithink you should be a nurse.” Or,the way you talk, you should be alawyer.” Plus I played the piano andI played the flute and even though Iwas terrible at it, people said Ishould go into music. So I had allthese ideas and somehow this ledto theater. If I had to do it all overagain, it probably would have led tofolklore, but at the time that wasn’tmentioned to me.And the thing was, I knew Iwanted to go to Howard University,and going to Howard I came acrossall kinds of people and movements.I was right there during the BlackArts, Black Power, Black HistoryMovements. And at the time, I startedwriting my own little things. Andmy teachers would put on thepapers, “This is so unorthodox. Butgo ahead.” I wasn’t conforming towhat was considered acceptabletheater or standardized theater atthe time. I guess I was more into anavant-garde thing, or trying to pullout some of my Black roots andthings like that.I was always relating things toback home. At the time, that wasconsidered unorthodox, because Iwas there to study Shakespeareand Ibsen.Again, being at Howard—youhad all these people comingthrough. You had LeRoi Jones (whobecame Amiri Baraka) comingthrough, and Ossie Davis, as well asEldridge Cleaver and MuhammedAli, you know. So this just put aspark in us. So I joined this groupcalled Theater Black. At first it wasTheater Noir, then it becameTheater Black, and then it becameWATTSA, and WATTSA stood for WeAin’t Takin’ This Shit Anymore! So itgot very, very, crazy, you know! Sowe were doing Malcolm X poemsand I wrote this poem called“Black.” You know, “You call meblack, white man…” Later, GlendaDickerson put it in one of her productions.I don’t even know all thewords to it. I just remember that atthe time, it became popular. Andwhat I started doing in my presentations,I started taking songs. Iremember taking Nina Simone’ssongs, and Johnny Taylor’s songs,and Langston Hughes’ poems and Iwould dramatize them. And I woulddo them in a way—it was kind oflike a storytelling thing, you know,and this would just excite thecrowd....And I was always still thinkingabout the folktales I had heard as akid, plus I was reading folktales,and I think the 60s was a timewhen a lot of collections were published.You know, HaroldCourlander and all these things,and Howard had a tremendouslibrary. Plus DC had these tremendousbookstores. So I was readingall these things, plus I was in the[Howard Student Center, calledthe] Punch Out sharing my tales ofhome, and I think things kind ofcame to a head for my senior pro-

ject. Because as a senior, you had todo a recitation or whatever. Andmost people would do scenes fromplays. And again, me and my avantegardeunorthodox self, I got upthere and did a whole thing of storytelling,telling stories, singing.But that kind of led me moreinto the storytelling and into thefolktales. Because I had been in thePunch Out just sharing stories fromhome, you know, about ‘splo and allthat kind of stuff. And I thougheverybody knew what ‘splo was.Because ‘splo was like home-brew,home-made liquor, you know. And Ithink the reason it was called‘splo- because that was like short forexplosion. And once you taste it—well, just the smell would knockyou. … So when I would talk aboutwhat was going on down inTennessee at the Punch Out someof the people were shocked.Because some of the people whocame to Howard at that time wereconsidered like the light bright.They came from the middle class.Their parents were like judges andlawyers and doctors and all of that.So some of the stuff I was sharing—some of them were embarrassed byit. Some of them had never heardof it.So a lot of these elements werekind of bursting out of me. And like Isaid, they kind of reached a head withme at Howard, with me still liking theaterbut kind of merging them together.And then I remember when myhusband, Clay, was a teacher there.And you had black poets, you hadblack dramatists, you had all this stuff,you know black, black, black, black,black, but there was nothing in termsof black storytelling, in terms of preservingthe folktales.And Stephen Henderson, he haddeveloped something called theInstitute for the Arts and Humanities.And he is really the one that startedbringing all the different Black Artstogether. Because, like I said, theBlack Arts Movement really cameout of the poetry and the plays. Andit was really almost like a Black malemovement, too. You had peoplesuch as Sonia Sanchez, who is oneof the people who emerged, but itwas really dominated by the men,you know. And they were going tohave this program and they wantedit to reflect all of the black arts. AndStephen Henderson was the onewho said, “You know, we need storytelling.We need a storyteller.” Andthat’s the first time that that ideaclicked in my head. And my husbandwas teaching in the departmentat the time, and he thought ofme, because I was telling stories, Iwas telling stories to him, I wastelling stories to my kids. So hecame home and he said, “Linda,” hesaid, “They’re looking for a storyteller.”And I said, “Well, here I am.”And that’s how I started, really.But that first program that I did.I think I told a story about BuhRabbit and I think I even did anAesop fable. I was just doing whateverI had been telling my kids. AndI remember I had all these cloths,and after I had done everything, itwas like people were just staring atme. It was like they had never seenanything like that before, just staring.I didn’t know if they liked it orwhat they felt. But then they comeup to me and they hugged me, andthey said, “Wow this is just unbelievable,this is something.” So fromthere, I said, well, this is what I’mgoing to do now. This is it. I’vefound my calling. Because that wasthe thing, trying to find your calling.So this was it.And being at Howard and beingat those times, I thought of storytellingas a political statement. Andthat’s where I come out of it. Like Isaid, I come out of the Black Artsand Black Power movement, and Iwanted to make a political statement.So I would use storytelling.And I would say “ancient tales fornew times.”And my audiences at the timewere adult. You know, because astory is an animal story, they tend tothink it is a story for children, but itis a story for everybody. So I wastelling these animal stories, but theywere really for the adults. And Iwould tell a story that almost kindof had a political thing to it. In otherwords, a person had to figure it outfor themselves, but the wholepower of a fable, of an animal storyis that even though you’re talkingon an animal, it’s taking on humancharacteristics. Also, you have toremember, this was a time duringthe Vietnam War. There was allkinds of things going on during thattime. So my stories tended to befables and animal stories but theywere stories again to kind of wakeup people. To kind of excite thecrowd, you know, to get people toreact, to express themselves. Andduring the 60s and 70s, you couldsay pretty much anything you wantedto say. There was no censorship,like there is now.And you’d hear all kinds ofstuff, and I remember Leroi Jonescoming to Howard’s campus, oncampus. They would do programson the steps, and he did this fabulousprogram. Nowadays we wouldcall it spoken arts, poetry, or thattype of thing. In those time, it didn’treally have a title. But to hear LeRoiJones do his poem “Up against thewall”…It was like nothing I had everheard before in my life! And he andhis manner, his mannerisms had theelements of what I would call storytelling.Because Leroi Jones woulddo his poetry to get the word out.In other words, he did whatever hecould to get the word out. He mightbe hollering or screaming or stompingand all that kind of stuff. Andthat’s the kind of stuff I wanted todo. So storytelling kind of gave methat outlet, where I could mimicpeople. Because I loved the idea ofmaking faces, I loved the idea ofmimicking people….I didn’t know that that was consideredan African way of telling astory. I was just telling a story thebest way I knew how. My influences—Imean coming from mymother, my father, my grandfather,you know, my aunts and uncles, the[Continued on page 21➝]Photo: Linda Goss and relativeson a rare snowy dayin Tennessee, c. late 1950searly1960s. Photos courtesyof artist.15

telling stories /continued from p. 1316tion for her daughter. And I wasstanding there. And finally the sistersaid, “Well, how about this littlegirl?” And the lady said, “I don’tknow her! She didn’t come withme!” And so the sister asked mewhat was my name. I knew myname and I told her that my brotherand my sisters went to that school,and I told her their names. So shesays, “All right. But you have to havea seat.” So I was elated! Because allof the kids were there, and theteacher, she was singing, and I’llnever forget: “A, B, C, D, E, F, G.…”And I learned my ABCs! But I wasn’told enough to be in school. And thething about it was, when we went torecess, we came out of the schooland went into the schoolyard, and Iwas standing there getting ready toplay something. And I looked at thegate and here came my mother. Shewas running—she didn’t know whathad happened to me. But Mr.Whitey had gone and told her, said“Mommy Lump said she was goingto go to school and I took herthere. “So when I saw here, I knew Iwas headed home. And I startedcrying. And the nun, Sister HelenRita, I remember her—She told mymother. She says, “Oh, don’t takeher.” She says. “Her brother or hersisters can take her home atlunchtime.” Because I was enjoyingmyself. And she let me stay.And my sister Lucy brought mehome at lunchtime. And evidently,after lunch I must have fell off tosleep because when I woke up mysister was coming in from school inthe afternoon, and I wanted to goback. I told her, “Mom, can I goback?” And when my sister came in,she was always loud. And first thingshe hollered out, “Sister wants toknow when Thelma’s coming back!”And that was it! I cried and I criedand I begged and I begged. So finally,she let me go the next day. So Istarted going to school! But theycouldn’t promote me because I wasn’tsix. And so they had me stay infirst grade for an extra school term.So that’s about it! That’s how I putmyself in school.I memorized poems when Iwas young. Just for myself. I lovedPaul Laurence Dunbar. His poetrystuck with me. At school there wasanother girl. Phyllis. Paul LaurenceDunbar seemed to be her baby. Andshe’d do that. So I would do otherthings. I loved rhyme. That’s how Iwould remember. One time I couldflip them right off. That’s what Ilove— it’s just like songs! You heara song and you like it, you hear itenough, you’ll learn the words.I guess I started writing in highschool. But I really didn’t push it.Because we had a girl. ChakaFattah’s mother, Frances Davenport,she was in my class at Southern.And Frances was the poet. So Inever even considered myself as apoet, right? Because you know howthey say who’s going to be what?Well, they said Frances was definitelythe poet. One teacher there said,there’re two girls in this room whohave a tendency to poetry. And shesaid, “Frances Davenport.” I knewthat. Then she said, “ThelmaShelton.” I said—“What?” I didn’tknow it! I didn’t even pay it any mind.When I was working for thecity, this guy was retiring and theywanted someone to write a verseand I happened to come into theoffice, and this little secretary—shesaid, talking about me, “She couldwrite it.” I said “OK.” And it wasn’tthat difficult to write, because thisman was comical, and everybodyliked it. So then, every time somebodyretired, they’d get me to writea verse. I gave away so manypoems. Because I didn’t think it wasanything special.And so then I started thinkingabout the different stories that fascinatedme: Corrine Sykes, Soldierson the Trolley. So I just wrote ‘emfor myself. I wrote Soldiers on theTrolley because my son, we weretalking one day, and he was inDrexel and he thought he kneweverything. So he was telling mesomething, and I said, “Oh yeah,that was like soldiers on the trolley.”And he said “What soldiers on thetrolley?” And the same thing forCorinne Sykes. He was instrumentalin my doing it because he didn’tknow about it. And I thought, well,if he doesn’t know about it, thereare a lot of people who have seenhistorical things, but they don’t payit any mind. They don’t say anythingabout it. And then children comealong and they’re shocked! Theynever heard that before.After I retired, I went to thispoetry reading. And I was just surprisedthat the people liked what Iwrote. Before that, I had a thing. Iwould always write. But I would neverread it. I’d always give it to somebodyelse to read. And so this way, atthe open mike, I started reading.And when I found out I wasn’tbeing laughed at, I went along withit. I used to just go for the openreading, and then Bob Smalls, Poetsand Prophets, he asked me to be afeatured reader. And that’s how Istarted. I had no intentions. I didn’thave even any plans as to what Iwanted to do after I retired. Butsomething came— and something Inever even dreamed about. I said,“I’ve been telling stories all mylife—but not this way!”I think that after I went to thatfirst reading, I said to myself, “Icould do that,” so after that, everybodyhad some kind of title, and Ido write in rhyme, so I said, “I’m apoetic storyteller.” That’s how Icome up with that. And then I hesitatedsaying that. I said to myself,I’m stepping too far.I’ve had a couple of olderwomen come to me and say, “Oh, Iwish I could do that.” If I can do it,you can do it, too! I don’t think anybody’slife is boring. If you don’twrite about yourself, you writeabout things that you see. And I dofind that people like to listen tosomething that they can relate to.That’s what I try to do. What Iwrite, it’s not any original story. It’sa story that I actually saw or heardabout that stayed with me. Lastingimpressions. That’s what it is, that’swhat I tell. The things that havestuck with me.Ms. Robinson will rell stories as part ofthe PFP “Self Knowledge” program onFebruary 19th. See next page.

PFP, ODUNDE & ART SANCTUARY PRESENT<strong>Folklore</strong> &Self-Knowledge:How stories tell us whowe are.February 19, 20051 PM – 5 PMChurch of the Advocate,18th and Diamond StreetsAdmission: $5 or a good story about why you don’t have it!(Three special prizes)An afternoon of stories andrecollections from pioneering AfricanAmerican scholars and storytellers:● Dr. Kathryn Morgan● Linda Goss● Thelma Shelton RobinsonFor everyone who’s ever listened to or loved a story, told alie, or struggled to find a truth. Pioneers in their own right,these scholars and artists of the spoken word will sharestories and talk about their own journeys in storytelling.Reading, telling, Q & A and discussion. Followed by a reception.Introduction by Lois Fernandez. Part of the Celebrationof Black Writing. In honor of ODUNDE's 30th anniversary andin memory of Gerald L. Davis. Don’t miss it!For more information visit www.folkloreproject.org,or call 215.468.7871

imagining louise madison/continued from p. 7Jersey. LaVaughn and friends tookseats in a remote corner of thenightclub and guzzled cherrygarnishedglasses of ginger-ale thatCy brought for them. Soon Louisehit the stage, dancing solo, deckedout in white trousers, white tails,and low-heeled shoes (“just like aman would wear,” LaVaughnadded).“She was doing so muchdancing, it was unbelievable.”Hercommand of the stage and thequality of her rhythms capturedadmired Madison’s dancing.(LaVaughn relates that a pot ofbeans and hog jowl was simmeringon the stove when they arrived, andLouise invited them to join her fordinner.) There were suspicions, orassumptions, that she was gay. Sheenjoyed a good card game,especially in the downtime spent indressing rooms between shows.Some of the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> tapveterans were convinced that shewas responsible for steering Babytone, hair texture, and facialfeatures—imposed by blacks aswell as white—and its impact onwho got what breaks, is a frequenttheme in the testimonies of thewomen featured in Plenty andother women entertainers of thatera. Or might she have been limitedby her choice to perform solo?While there were other womenwho had solo acts, (the Stearnsassert that if women dancers weregood, they usually performed alone,This page:Hortense AllenJordan and LibbySpencer in finale of“Stepping in Time,”February 1994. Nextpage: Libby Spencerrehearsing dancers for“Stepping.” Photoscourtesy Jane Levine.18LaVaughn’s attention andembedded themselves in hismemory, such that, more than a halfcentury later, you can still hear theexcitement in his description ofthis first encounter: “She was doingas much dancing as any tap loverwould ever want to see!”About adecade later, in 1955,LaVaughn, bythen a professional hoofer,encountered Louise when theyboth were on a show at New York’sApollo Theater. Once again, he wasawed by her style and techniqueand she was generous with herencouragement to LaVaughn andhis dance partners.Despite Louise’s popularity withaudiences and the respect shecommanded from her peers, little isknown about her career or privatelife.What glimpses there are tend tobe fragmented and disconnected.We know that she lived in North<strong>Philadelphia</strong>: LaVaughn once visitedher along with master tap dancerJerry Taps Sealy, who greatlyLaurence to abandon singing fortap dancing—a career move thatresulted in Laurence becoming ajazz tap icon. Marshall and JeanStearns, in their classic volume JazzDance:The Story of AmericanVernacular Dance,credit Louisewith “cut[ting] a five-tap Wing like aman.” 1 It’s not clear when or whyshe retired from performing.Entertainers who were Louise’speers wondered and speculatedwhy, given her stage presence andtechnical skill, she did not have alonger and more successful career.(As LaVaughn put it,“why she neverdid make it like she should have”).Without a doubt, opportunitieswere limited for black performersin general, and especially forwomen who dared to pursue sucha male-dominated domain as tapdancing. But beyond theseconsiderable hurdles, was shehampered, as Dave McHarrispronounced, by her looks? Thetyranny of attitudes toward skinas soloists), 2 it seems that theconvention of the time for bothmen and women hoofers was toperform in teams of two, three, orfour dancers—although outside ofchorus lines, it was relativelyuncommon for women to performin an all-female ensemble. LaVaughncites a business motive for theprevalence of duos, trios, etc., inthat agents could demand biggerfees, and realize largercommissions, for a team than for asingle tap dancer. Otherexplanations include IsabelleFambro’s perspective that her andher partner’s act, Billy and EleanorByrd, was designed to capitalize onthe popularity of Marge and GowerChampion, who were theprototypical white elegant stagecouple. For Baby Edwards, workingwith a male partner gave herprotection and a sense of securityon the road.Was Louise’s use of male attireonstage off-putting to agents and

presenters? Other femaleforerunners and contemporaries ofLouise donned suits, ties and lowheeledsuits. Mildred Candi Thorpeand Jewel Pepper Welch, of the<strong>Philadelphia</strong>-based team of Candiand Pepper wore zoot suits andWindsor-knotted ties.Wheninterviewed in the early 1990s,Candi noted that “people wanted tosee flesh but we never exposed ourbodies.” Indeed, one of the mostsuccessful and durable acts into speculate on what social factorsand personal choices might havedriven or hindered Louise’s dancecareer,we will have to contentourselves with what little we know ofher.It has been many years since shecould speak to us in her own voice,and it is unlikely that her survivingcontemporaries can illuminate thedetails of her life and talent more thanthey have already.But even if a troveof data lay right around the corner,Ithink I would prefer the Louise in myvaudeville, the Whitman Sisterstroupe, featured one of the sisters asa male impersonator. But I wouldn’tunderestimate the ambivalencethere might have been in Louise’stime toward women who dared tochallenge convention by not onlypracticing a male art form, but alsopresenting themselves dressedlike men.A personal experience thatoffered me a glimpse of attitudesthat Louse Madison and her peersmight have encountered occurredin 1989 when LaVaughn and I were inNew York City taping the PBS special,Gregory Hines’Tap Dance inAmerica.LaVaughn and I,bothdressed in tuxedos,had just finishedour up-tempo,wing-filled rendition of“How High the Moon.”The wife of taplegend Bunny Briggs came backstageand congratulated me on my dancing,then added,“Dear,you need to getyourself a little skirt.At first I thoughtyou were a young boy up there.”As intriguing as it is to theorize,imagination—the Louise conjuredfrom a few scraps of potentstorytelling,the Louise whose powersof self-invention and whosewillingness to challenge custom andconvention are unsullied byinconvenient facts.I prefer the Louisewhose technical and stylistic muscleis immune to comparisons withgrainy film footage and offhand,possibly uninformed,critiques.Ichoose the Louise in my imagination,the one that was,in LaVaughn’swords, unbelievable.1NY: Macmillan, 1968, p.1952ibid, p. 195●●●Long-time PFP board memberGermaine Ingram initiated the PFPTap Initiative which includedinterviews with veteran <strong>Philadelphia</strong>hoofers, and which resulted in theproduction Stepping in Time, and thedocumentary and exhibition Plentyof Good Women Dancers. Germaineis currently a consultant oneducational and child welfare policyand programs.To purchase the newlyreleased DVD Plenty of Good WomenDancers, see p. 20, or visit ourwebsite. Plenty will be broadcast inthe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> area on March 28,2005 at 10 PM on WHYY-TV 12.19

Plenty of GoodWomen Dancers:african american women hoofers from philadelphiaThis long-awaited documentaryfeatures exceptional local AfricanAmerican women tap dancersNOW AVAILABLE!whose careers spanned the 1920s-1950s. Restricted to few roles,often unnamed and uncredited, these women have a story to tell!Glamorous film clips, photographs, and dancers’ own vivid recollectionsprovide a dynamic portrait of veteran women hoofers prominentduring the golden age of swing and rhythm tap.Plenty was directed by Germaine Ingram, Debora Kodish, and BarryDornfeld, and produced by Debora Kodish and Barry Dornfeld.53 minutes. 2004. DVD. $24.95 individuals, $65 institutions.ISBN 0-9644937-6-4.TO ORDER:____ (number) of Plenty of Good Women Dancers (DVD) @ $24.95=+PASales Tax @ 7%__________________+ Postage/handling ($3 for 1-5 items, $5 for 5-10 items. _________MAILING INFORMATION:Total Due_________Name:_______________________________________________ Phone:_________________Address:_____________________________________________ Email: __________________City:____________________ State:_________ Zip: _________Make checks out to <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, and mail to PFP, 1304 Wharton St., Phila., PA 19147.Questions? 215.468.7871 or info@folkloreproject.org. THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT!order with credit cards atwww.folkloreproject.org

waking up the people/continued from p. 15town itself…and then hearing peoplelike a Amiri Baraka or a JayneCortez, a Sonia Sanchez and alsoseeing and hearing Sun Ra andOrnette Coleman and PharaohSaunders and Sonny Rollins—andonce you started seeing these people,and hearing these people…andall this just kind of came togetherfor me so that I emerged.And the whole thing with mewith storytelling was to not only tobe influenced by my culture butalso to develop my own thing. I’mthe kind of person that I want to beunique, no matter what I do....So even with my storytelling,I’m always looking for ways, exploringit, taking it out, take it in differentdirections, you know, becauseto me storytelling is so powerfuland I think it is so important and socrucial to really get the story out.And I think of storytelling, really, asa force, and I think of it as a survivaltool, and I think that’s how we as apeople survived, and I think that’show people— human beings as aspecies— will continue to survive—if we get the story out. And I thinkwhat’s happening now is really asuppression of the story, of theword, getting out.I was so shocked when I heardthere were other storytellers,because I thought I was so unique!I thought. “Oh boy, I’m the onlystoryteller in the world!” I think thefirst storyteller I started hearingabout was either Brother Blue orMary Carter Smith. They had atremendous influence on me, especiallyBrother Blue, because he wasso different, he was so unique and Iwas influenced by that.Apparently, talking to BrotherBlue and Mother Mary, they kind ofstarted doing their things around’73, too. Something happened, inthe 70s, that led to the storytellingmovement. Now what or why, Ihaven’t been able to figure out.Why people were driven or drawnto this, you know, because peopleleft their jobs, they started saying“this is what I am going to do,” typeof thing.And what was so funny, I was discouraged,too. See, I don’t want youto think that everything was all roses,because it wasn’t. Sometimes peopledidn’t know what I was talking about,what I was going to do.And at the time I was very disappointed.I was very, you know,discouraged, and I think that’s whatkind of reminded me of the storymy grandfather used to tell aboutthe frog who wanted to be a singer,how you had to keep going andthat was a story I was telling to mykids anyway. And that kind of ledme to telling that story in public.They started the SmithsonianFestival of American Folklife andBernice Reagon was at Howard and[my husband] Clay and her wouldtalk and she heard about what I wasdoing and she said, “Well, maybeLinda should be featured.” And Iremember that I had to kind of likecome and audition for her. And Iwas so afraid, so nervous. I couldhardly talk. I was stuttering,because I stutter anyway. I couldhardly move. My feet were sowooden. And I really did a horriblejob. But it was something in me,something she saw. And sheencouraged me, and she said, “Well,you can come and you can tell yourstories.” And I just remember shesaid, “I just hope you”—I remembershe pointed to my feet—“I justhope you move your feet alittle more. “And then in ’75 they had me totell stories. But one year, when Iwas there, they had me to comeout of this shack, which was similarto what was in my home town, andthey even had a garden. And Inever will forget. And I thinkBernice just said this. But theydidn’t have—they didn’t give me amicrophone. Either they couldn’tfind a microphone or they forgotthat I would need one. So Bernicesaid, “Just use your voice. Just useyour voice. Use your voice. They’llcome. They’ll come.” So that’swhen I started doing this cry: “Well,oh well, well!” Before I had neverdone that, to the public. But I wantedpeople to come and hear thestories! And I had all this so-calledcompetition because, you know,people from all over the world werethere, sharing their art, their folklore.And how was people going tocome and look at little old me, youknow?! And I just started going “Well,oh well!” “Story! Story-telling time!”“Well, oh well, well,” that camefrom a little man called Squeal ‘emCarr. Now to this day I do not knowhis real name. Because a lot of peoplein my town have nicknames.Everybody has a nickname. Youknow the Negro Leagues, the baseballteams, would come though thetown and they would play in thisbig field that isn’t there anymore,you know, and whenever there wasa home run, you could hear “Well,oh well, well!” and it just took meout! It was like, “Who is that?! Whois saying that?!” Again, I was curious.I always had the questions.And my mother said, “That’s Squeal‘em Carr,” you know. And my motherwould sing it around the housetoo. In other words, that becamelike something people would sayaround the town, because youthink of Squeal ‘em Carr and thatsaying, you know. And one day, Isaw Squeal ‘em Carr, and he was sotiny. He was a very short man. Andthe whole idea of something thatpowerful, that you could hear allover that field, coming out of hisvoice, you know. So apparently,when Bernice said “You’ve got tocall ‘em,” that is what came outof me.And what happened next, Ibought some bells. These are bellsthat I have been using ever sincethe 70s. I thought that since I amgoing to be at the Smithsonian, andI’m using my voice—I got to dosomething else [to attract people]so I started ringing the bells.And so, once I kind of emergedas a storyteller, and when I told mygrandfather what I was doing, that’swhen he brought this old bugle,this old bugle he had. I’d neverseen it before. And he told me thatwas his job. On the plantation. Hehad worked in this big plantation inAlabama. Now, you know, my grandfather,he always got to tell a story.And again, you didn’t know whatwas true and what wasn’t. But heclaimed that the rooster wouldcrow first, early in the morning. Therooster would crow. And when therooster would crow, this wouldwake up Shep, the dog. Then thedog—now again, the way he wouldtell it, it would sound like the[Continued on page 23➝]21

supporterspfp video:Look forward andcarry on the past:stories from philadelphia’schinatownTouching on community efforts to stop a stadium from being builtin Chinatown (one of many fights over land grabs and “development”),and on other occasions when the community comestogether (including Mid-Autumn Festival and New Year), this documentaryattends to the everyday interactions, relationships, and labor—so often overlooked—that build and defend endangered communities.Directed by Debbie Wei, Barry Dornfeld, and Debora KodishSPECIAL DISCOUNT FOR PFP MEMBERS!$15 INDIVIDUALS (Members $11) $50 INSTITUTIONS (Members $37)ORDERName:FORMAddress:City:Phone:State:Email:Number ordered:Amount enclosed:Please make checks payable to: <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>Mail to: PFP, 1304 Wharton St., Phila., PA 19147Walking on Solid GroundA new children’s book about <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s ChinatownBy Sifu Shu Pui Cheung, Shuyuan Li, AaronChau, and Deborah Wei. A children’s bookabout <strong>Philadelphia</strong>’s Chinatown, told fromthe point of view of two artists and theiryoung student. Walking shows people takingrisks and struggling to hold on to communityand folk arts— things which money simplycannot buy. 32 pp. Photographs. BilingualChinese/English. $12.95 + $1.50 postage22Please make checks payable to: <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>Mail to: PFP, 1304 Wharton St., <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, PA 19147

waking up the people /continued from p. 21truth!—the dog would come andlike lick his hand. And that wouldwake him up, and then he wouldget the bugle and then he wouldblow—mmmmm—and that wouldstart waking up everybody. Now Ibelieve it, because that’s what hesaid. And so he says, “I had to wakeup the people to get them to startworking.” He said, “And that’s whatyou’re doing. You’re waking up thepeople.” So he gave me the bugle.And that was so odd. Becausebefore that I did not know that’swhat he did.A lot of the times, you mightdo something, you don’t knowwhy you’re doing it, you don’t knowwhere it comes from. You don’tknow if they can trace it back toAfrica if you’re aware of it. Youknow, you just start doing it. Sothat’s something I just starteddoing, you know!And at DC, at the Smithsonianthing, these crowds just kept going,would gather around. And one ofthe people who saw me, who heardmy stories was Louise Robinson,She was one of the original membersof Sweet Honey in the Rock.So a lot of them came, they wouldsee what I was doing. And one ofthe members [of Sweet Honey] nowuses, tells the frog story I tell, andalso the Stuart sisters, Ardie StuartBrown [came], and it kind ofinspired her to develop what shedeveloped. And so what I starteddoing kind of led to a movement.●●●Linda Goss was born near theSmoky Mountains in an aluminumfactory town, Alcoa, Tennessee. Shegrew up listening to the storytelling ofher grandfather Murphy and otherfamily members who shared stories oflife under slavery as well as a heritageof folk tales, oral history and legend.Stories about ethical values, the civilrights struggle in Tennessee, and storiesfrom personal experience are amongmany hundreds of stories that she hasgathered over decades of serious studyand performance. She is currentlyworking to document play-party songs,as well. The "Official Storyteller" of<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, and a pioneer of the contemporarystorytelling movement, Ms.Goss was co-founder of "In the tradition…"the National Black StorytellingFestival and Conference and TheNational Association of BlackStorytellers, a founding member ofKeepers of the Culture, and ofPatchwork: a Storytelling Guild. She isthe author of numerous books, and acontributor to many collections onAfrican American storytelling. She willbe sharing stories as part of PFP’sFebruary 19th program (see calendarto right) and will be leading a 3-partseries of storytelling round-tables at ournew home. For more informationabout these events, and about Ms. Goss,visit www.folkloreproject.org.2005pfp•calendar>grants workshopsJan 15, Mar 19, May 21: BUILD SKILLS.Help for folk arts projects. 10-Noon. Call for details.>studio visitsFeb 8, 16, 19 & 26: BEHIND-THE-SCENESVISITS WITH PHILLY ARTISTS: Kulu Mele,Herencia Arabe, Ollin Yolitzli in rehearsal. Call for details.>storytellingFeb 19: FOLKLORE & SELF-KNOWLEDGE.@ Art Sanctuary, 18th & Diamond, 1- 5 PM. $5 See p. 17.>workdaysMarch 26, April 2 & 9: HELP US GET THENEW PFP BUILDING IN SHAPE! Paint, clean, &make our garden grow with master heritage gardenerBlanche Epps. 9 AM @ 735 S. 50th St. All welcome.>exhibitionsApril 15: “IF THESE WALLS COULD TALK”EXHIBIT OPENING. After 18 years of being a tenant,the <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong> is going to own our own home, andour new dining room is a work of folk art and social history.5-8 PM @ 735 S. 50th St.May 13: “WE SHALL NOT BE MOVED:”THOMAS B. MORTON: 30 YEARS OFODUNDE photo exhibition opening. 5-8 PM@ 735 S. 50th St.>salon performancesMay 4, 11 & 18: LINDA GOSS: Storytelling Table! 7PM. 735 S. 50th St. $10. May 8: ELAINE & SUSANWATTS: Klezmer. 2 PM. 735 S. 50th St. FREE. May 22:GERMAINE INGRAM: Tap Dance. 230 PM@ Indre, 1418 S. Darien. $10.>grand opening (of our new home)Sept. 13: SAVE THE DATEWANT TO LEARN MORE? For details, visitwww.folkloreproject.org, or call us and we’ll send you a fullcalendar: 215.468.7871.

about thephiladelphia folkloreproject<strong>Folklore</strong> means something different to everyone—as it should,since it is one ofthe chief means we have to represent our own realities in the face of powerfulinstitutions. Here at the PFP, we’re committed to paying attention to the experiences& traditions of “ordinary”people.We’re an 18-year-old public interestfolklife agency that documents,supports & presents local folk arts and culture.We offer exhibitions, concerts, workshops & assistance to artists and communities.Weconduct ongoing field research, organize around issues of concern,maintain an archive, & issue publications and media. Our work comes out ofour mission: we affirm the human right to meaningful cultural & artisticexpression,& work to protect the rights of people to know & practice traditionalcommunity-based arts.We work to build critical folk cultural knowledge,respect the complex folk & traditional arts of our region, & challenge processes& practices that diminish these local grassroots arts & humanities.We urgeyou to join—or to call us for more information. (215-468-7871)____$25 Basic. Magazines like this 1-2x/yr, special mailings and 25% discounton publications.____$35 Family. (2 or more at the same address).As above.____$60 Contributing.As above.($35 tax-deductible)____$150 Supporting. As above. ($125 tax deductible)____$10 No frills. No discounts. Magazine & mailings.____Sweat equity. I want to join (and get mailings). Instead of $$,I can give time or in-kind services.____$ Otherjoin now!membership formNameAddressCity State ZipPhoneE-mailPlease make checks payable to:<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>Mail to:PFP1304 Wharton St.,<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, PA 19147thanks to new and renewing members!Please join us today!Visit our website: www.folkloreproject.org<strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>1304 Wharton St.<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, PA 19147NON-PROFIT ORG.U.S. POSTAGEP AIDPHILADELPHIA, PAPERMIT NO. 1449magazine of the philadelphia folklore projectAddress service requested