Tatreez - Philadelphia Folklore Project

Tatreez - Philadelphia Folklore Project

Tatreez - Philadelphia Folklore Project

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

home*place

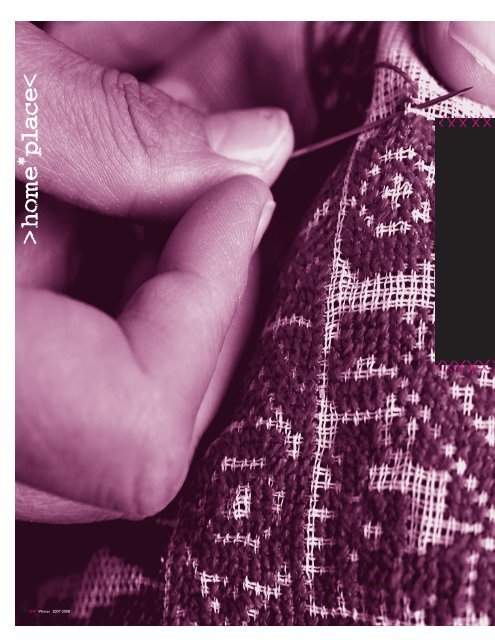

Alia Sheikh-Yousef and her needlework.Photo: Sarah Green, 2009by Nehad Khader<strong>Tatreez</strong>:palestinian women’sneedlework in philadelphiaI grew up watching my mother, Alia Sheikh-Yousef, stitch patterns intofabric on the weekends and after work. This was my introduction to tatreez—traditional Palestinan needlework. My mother's creative works would besewn together by my grandmother in whatever way my mom wanted. Thesewomen turned panels full of intricate tatreez designs into cushions, wall hangings,tablecloths, and dresses. Observing their pieces more closely revealedthreads of all colors, chosen carefully, interweaving their way through oneanother to create a flower, a bird, or multiple triangles. But to me, a child, thiswork only represented my mother's talents and her desire to decorate herhome. I didn't know where these patterns came from—that certain designscame from particular villages or had a long history, recognizable to theirmakers. Nor did I understand the reasons behind this needlework until theoutbreak of the second Palestinian Intifada, or uprising, in September 2000.[Continued on next page >]2009 Summer/Fall WIP 7

<strong>Tatreez</strong>/continued from p. 7<strong>Tatreez</strong>:palestinian women’sneedlework in philadelphiaExhibitionThrough December2009For a 15-year-old PalestinianAmerican girl, the images ofPalestinian youths—most of themmy age—throwing rocks at tanks andparticipating in a popular resistancemade a lasting and deep impression.I began searching my home, ourbooks, even my facial features forsomething that would bring me closerto those youths and to my homeland.Not surprisingly, I found value in mymother's art, a Palestinian art thatshe learned from other Palestinianwomen. I learned that my motherwas stitching our heritage and historyinto fabric. I wanted to participatein this process. My mother taughtme tatreez, and in the process Iwas educated in the philosophy ofthe art as a method of resistance,as a means to preserve Palestinianheritage, and as a contribution tothe Palestinian collective memory.These processes are extremelyimportant to us Palestinians,a Diaspora people, scatteredworldwide after a forced exile.My family is part of this exile.Both sets of my grandparents wereexpelled from their homeland in 1948.My father's family comes from thevillage of Umm el Zeinat, just outsideHaifa. My mother's father also comesfrom there, and her mother from thecity of Haifa. My father's family wasexiled to Iraq and my mother's toSyria, where they lived as refugees.Neither of my parents has been totheir homeland, but both are deeplyconnected to it and desire to returnone day. It is this history that I beganto explore in the last year as part ofa project to find and document thework of other women who stitchtatreez in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>—a project thatculminated in the exhibition "<strong>Tatreez</strong>:Palestinian Women's Needleworkin <strong>Philadelphia</strong>," now on display atthe <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Project</strong>.For centuries tatreez has beenthe creative, financial, and fashioncapital of Palestinian women. Longago, a woman’s social status and8 WIP 2009 Summer/Fall

From left:Wall hanging by Wafa Ajaj.This resembles the chest panelfor the thob. Alia Sheikh-Yousefand her needlework.Detail of stitching on oneside of neck scarf, made byAlia Sheikh-Yousef:Moon of Ramallah, birdsand cypress.Photos: Sarah Green, 2009geographic origins could be identifiedfrom the stitch, fabric, and cut of herthob, the traditional embroideredPalestinian dress. As soon as shewas able, a young girl was taught tostitch her own dresses. Typically shebegan preparing for her marriage: shewould cross-stitch everything fromher wedding dress to pillows for herhome and personal handkerchiefs.Then, when expecting her first child,she would compete with the otherwomen, passing the months of herpregnancy preparing with her ownhands an elaborate cross-stitchedwardrobe for her daughter or son.<strong>Tatreez</strong> has changed tremendously,both in practice and in use, and thischange is connected to the majorstructural changes in Palestinian life.In 1948, 75 to 80 percent of thePalestinian population was expelledfrom their ancestral homes andvillages in a massive ethnic cleansing.We call this our nakba, "catastrophe."In place of our homeland the state ofIsrael was created, and the majorityof Palestinians became refugeesor internally displaced people, acomplex crisis involving our identities,livelihoods, and quality of life. Thecommunity that had been heldtogether by physical space and landbecame a community connected bya cause: liberation, homeland, andidentity. As a Palestinian art, tatreezis an expression of identity, andthus oftentimes political: a way ofpublicly and visibly stating—insistingon—who we are, a way of claimingour connection to a homeland and toone another. After the nakba and tothis day, many women used tatreez tosupport themselves, making and sellingclothing for wealthier women. When Ibegan fieldwork in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>, I hadno idea whom I might find who stillmade tatreez. Nor did I knowwhat uses this art might still have.Today, for the women I interviewed,the economic uses of tatreezare less important: none of themsell their work, and all alive more[Continued on p. 20 >]2009 Summer/Fall WIP 9

<strong>Tatreez</strong>/continued from p. 9comfortably than our sisters inrefugee camps. For local women,tatreez is about claiming identityand sustaining collective Palestinianmemory.I worked with seven women forthis exhibition, including my motherAlia Sheikh-Yousef. Each one has aunique story about how she learnedtatreez, what she makes, and whyshe makes it. However, commonthemes arose in our conversations.<strong>Tatreez</strong> is always communal insome way, connecting each artistwith other women both withinthe family and outside it. All thewomen express pride in tatreez, apride that stems from preservingthe art of a Diaspora peoples wholive with a contested identity andunder perpetual occupation. It isan example of cultural resistance:we are maintaining the existence ofthe Palestinian people through ourstitched heritage.We, the artists, see ourselvesas beacons of our heritage. Wefeel responsible: we have inheritedthis tradition and cannot stopcreating. All the women interviewedexpressed a hope that youngergenerations of Palestinian womenwould learn tatreez and find theirown uses for it. And just as we haveinnovated within the tradition to suitour changing lives, we hope that thenext generation will do the same.Most importantly, these artists hopethat young women will preserve theart of tatreez for other generations.Older women lament that othershave turned to machine-madePalestinian dresses. (In their opinion,the quality is lower, and the effortis absent.) Local women all highlightthe hard work and labor that goesinto each handmade piece—fromdesign to stitching to thinking ofhow the piece will be sewn intothe final product. Their work is anaccomplishment to be proud of andto display for people to enjoy.Seven women are featured inthe exhibit, and tatreez connectsthem to the homeland in variousways. Some are motivated to takeup this art by the idea of Palestine.For others, tatreez is importantbecause it is about the particularpeople—family and neighbors—whocreate and sustain the memory ofthe homeland with their needlework.And while each woman is Palestinianand practices the same artform asthe others, each has a unique historywith tatreez and attributes differentmeanings to it.Umm el Adeeb is from the villageof Jaba’ but got married and livedin Mukhmas: both villages arebetween Ramallah and Jerusalem.Her hometown, on the occupiedWest Bank, continues to exist, neverdemolished by war. She learnedtatreez from her mother at an earlyage and remembers her motherevery time she sees an older womanwearing a thob. After she beganhaving children, she stopped makingtatreez until her youngest daughterwent to school. Then she beganmaking embroidered thyab to wearwhen she returns to Mukhmas. “Inyour own country you look fancy,”she explains, “not like here, wherepeople are going to make fun ofyou.” She embroiders panels thather mother sews into dresses for herwhen she visits <strong>Philadelphia</strong>.Today Umm el Adeeb has anextensive collection of embroidereddresses. She keeps most of themin her home in the West Bank. Sheis particularly fond of a group thatshe made out of lighter and coolermaterial for the summer heat ofMukhmas. The women in Mukhmaslove her dresses, and she is proudof her innovative ideas. When sheturns over a panel to point out thedetails, the stitching on the back isextraordinarily neat. She no longerstitches, for lack of time, but lastsummer she came to the Al-BustanCamp (a summer camp teachingArabic culture to young people in<strong>Philadelphia</strong>) and, along with mymother, taught the young campershow to make tatreez. She showedher own work and spoke with theolder campers about her homelandand family.In the home of Wafa Ajaj I learnedthat this art is not public, though itis not necessarily private either. Sheopened her home to me warmly, andon my first visit I ate and drank teawith her nieces and daughters. WhenSarah Green came to take pictures,Wafa began rearranging her furnitureand bringing out all of her handmadepieces. Her three grandchildren—Talal, Aouni, and Nahid—endedtheir noisy play, mesmerized bythe importance surrounding theirgrandmother at that moment, andsurprised and curious about herability to create the artwork aroundthem, which until that momentthey had taken for granted. Theywanted to photograph the tatreezthemselves, be photographed withthem, and make absolutely sure thattheir grandmother, astonishingly, hadproduced those pieces.Wafa Ajaj learned tatreez fromher mother. She remembersgathering outdoors with her sistersand the young women from theneighborhood to make tatreez in oneanother's company. They would drinktea and hold friendly competitions tosee who would finish the most ballsof thread, or tubba. Wafa smilednostalgically as she remarked thatthe tatreez around her remindedher of family and friends in Ramallah,especially her mother and hermother-in-law. She also made dressesfor her daughters when they wereyoung, pointing out that “the youngwoman is proud of her heritage, sheis not ashamed of it.” These giftsof time and handwork connectedgenerations, making and sharing asense of pride and beauty.For Arij Yousef, too, this art isrooted in family. In her thirties, sheis one of the younger artists. She wasborn to a Palestinian father and anIraqi mother and lived in Amman andCairo before settling down in theUnited States. She learned tatreezin 2008 while visiting her family inJordan. Learning the traditional art20 WIP 2009 Summer/Fall

<strong>Tatreez</strong>/continued from p. 20of her Palestinian family was a wayof bonding with her sisters and hergrandmother, Umm Hasan, who wasexiled from Jerusalem in 1948 andnow lives in Amman. At the age of102, Umm Hasan still embroiders:last summer she and her othergranddaughters taught Arij how toembroider as well! Arij took to thisart, puzzling out patterns from oldermodels and enjoying the chance tocreatively adapt traditional patterns.The women have become veryclose to each other thanks to tatreez.Umm Hasan sent Arij home witha traditional Palestinian thob madeof black cloth embroidered in redthread and a jacket embroidered frontand back in a variety of colors andlayers of patterns. Her grandmothertold Arij that as fallaheen (farmers),women looked to the colors ofnature for inspiration: the brownbark of a tree, a red bird, or theblue sky. Arij lives in the city, butshe is still inspired by nature, asis evident in her colorful work.Arij’s favorite pastime sincereturning to the United Statesis tatreez. She has taught it toseveral women in her family herein <strong>Philadelphia</strong>. Because the propermaterials are often difficult orimpossible to find in craft shops inthe United States, she brought backcanvas, thread, needles, and books,which she distributes generously.(Canvas is used to provide gridlinesfor the cross-stitches; when the artistis finished, the canvas is removed,leaving only the stitches and fabric.)When I complained about my ownneedle, she advised me to use a dullone, and gave me several of hers, andshe gave my Aunt Ghalia, anothercontributor to the exhibit, a bookand sewing materials to take back toher home in Norwich, Connecticut.Ghalia Salahi is my mother’solder sister. While my mom and heryounger sister, Samia, were workingand studying in the Arab world (Aliain Damascus and Samia in Amman),Ghalia was obtaining a master’sdegree in math education here inthe United States. Aunt Samia madea dress for my grandmother in thetraditional thob style—black clothstitched in red on the chest panel,along the sides, at the bottom ofthe sleeve, and on the bottom ofthe back of the dress. I wore it formany years in my Palestinian folkdance troupe. My mother made amore modern dress for Aunt Ghalia:it is navy blue, falls just below theknee, and is stitched extensively onthe chest panel in various colors.These works are treasures, waysin which our relationships to oneanother, to the past, and to ourhome villages are made visible.Seeing the works that her sisteswere producing, Ghalia becameinterested. She began work on apractice piece many years ago, andshe still stitches on it to test outpatterns. Her stitches have becomevisibly larger over time. Our lives andthe years are traced in this work.This exhibition project inspired her,and all the women of my family, tocarry their pieces around and sharewhat they’ve accomplished, to copypatterns and search for ideas, andto finish pieces started long ago. Atext message from my aunt recentlyshowed me her most recent piece:a wall hanging for her son’s newhouse, incorporating the colors ofhis favorite sports teams. She startedit months ago but completed it onlytwo weeks after visiting the galleryas I worked on the installation.Sisters Maisaloon and Wafai Diasare the youngest women whose workis included in the exhibit. Maisaloon isa social worker in her mid-twenties,and Wafai is a high school senior. Bothwomen learned from their mother,a seamstress who also made tatreez.She used to embroider her ownpanels and sew them together intodresses, and Maisaloon and Wafairemember how she would ask themto sit near her while she workedand help her by removing the canvasbetween the stitches and the fabric.As the girls grew older, they becamemore interested in the creation of theart. Their mother gave them panelsand a pattern to follow. “She did itfirst,” Wafai said. “She showed us howto do it, and we tried to repeat it asbest as we could.” They laugh as theyrecall that their mother abandonedplans to make those panels into adress when she saw how uneventheir stitches were! Now they areaccomplished needlework artists.Maisaloon and Wafai's mothernever sold her own tatreez, but localwomen would bring their handmadetatreez panels for her to sew intodresses. Business decreased overthe years, as women started tobring ready-to-wear dresses andask her to adjust them. The sisterslament this change and were excitedto find a community of womenwho continue to make tatreez.I undertook this project for manyreasons. <strong>Tatreez</strong> is an integral partof our lives. After the backlash ArabAmericans faced after September11, 2001, I wanted the Americanpublic to see alternative images of usthat represent us more accurately. Ialso wanted to introduce the youthin our own community to storiesof our heritage, fearing that theywere too often being exposed tostereotypical and negative mediaimages of themselves. <strong>Tatreez</strong> isaccessible as a traditional artformbecause of its presence in ourlocal community. The youth, girlsin particular, can learn a great dealfrom the artists, as I myself learnedfrom them—both about this art andabout Palestinian women’s lives.Within the first few interviews,I discovered how personal tatreezis, and how much it pertains to thehome. Wafa Ajaj says that her workis beautiful art for her home: noneof these women ever shared theirwork in a public exhibit—nor didany of them ever sell their work.Instead, patterns are traded, panelssewn on by several women, andideas exchanged. Yet all of themagreed with the mission of theproject and were happy to tell their[Continued on p. 29 >]2009 Summer/Fall WIP 21

tatreez/continued from p. 21stories to the public and displaytheir work. The exhibition becamea new means of sharing with oneanother and becoming visible—asartists and makers of beauty andcommunity—to a wider public. Theywere generous with their time andtheir tatreez, and for this I am grateful.The women involved, includingmyself, range in age from their teensto 102, so I can proudly say thatthis art is not dying. Nor are theidentity issues tied to any Palestiniantraditional art diminishing. Far fromhome and heritage, we can insist,with these stitches, on our rightto name ourselves in connectionwith the places and people wecome from. Thanks to my workon this first exhibition project, myAmerican-born cousins Nehad, 15years old, and Dania, 13, have takencanvas and string and are currentlylearning tatreez by stitching theirnames. This is how I myself learnedtatreez at the age of 14. These newsettings encourage us all to imaginemany kinds of future for this art.Traditionally, a woman learnedtatreez from her mother and passedit on to her daughter. But my motherlearned it differently. Her mothernever made tatreez because shecomes from the city, and only villagewomen made tatreez. Even thewomen of my father’s village neverwore tatreez. However, when mymother lived in the Yarmouk RefugeeCamp for Palestinians in Damascus,she organized exhibits of tatreez andhelped women in the camp to selltheir work. Her passion for everythingrelated to her homeland led her toask these various women to teachher. It became her favorite pastime,“because tatreez is mobile,” shepoints out. “You can pass it aroundamong people, and that way youpreserve it.” In a different setting, Itoo find myself creating a new contextfor showing, sharing, respectingand learning about this tradition.I am very happy about the supportI’ve received from the Palestiniancommunity for this project. During thejam-packed exhibition opening, Alia,Arij, and Umm el Adeeb graciouslyanswered questions, responded tointerested and enthusiastic attendees,explained the process, and talkedabout individual pieces. They arenow also looking forward to leadingworkshops and teaching the art. Ourhope is that we can forge a new andlasting space for tatreez in <strong>Philadelphia</strong>and continue to build communityand understanding around the art.Most importantly, we want youngPalestinian women to learn abouttheir heritage and history throughtatreez and find pride in their identity.—Nehad KhaderAttendees atthe tatreez workshop.Photo: Thomas Owenshomesickness /continued from p. 18camp told stories with musical anddramatic flair and performed the dancesthey had learned, accompanied by abattery of drummers. Their teachersoffered short performances, andeveryone enjoyed lively talk over a feastof traditional Liberian foods preparedby the mothers of some of thestudents. A day later, in the courtyardof a beautifully ornate Khmer BuddhistTemple, Cambodian camp studentsperformed their dances and drummingin the bright sun and brisk breeze ofa Sunday afternoon. The Chief Monk,members of the temple, and residentsof the surrounding South Phillycommunity—merchants, seniors, kidsout riding their bikes—joined parentsand grandparents for the demonstrationand an open-air buffet of Cambodianfried rice, noodles with curried chicken,and spring rolls prepared and servedby the temple’s food committee.By all the conventional measures,the camps were a success. Kids,parents, artists, and staff were happywith the experience and lookingforward to the next one; there wasdemonstrated growth in students’skill and knowledge; no emergenciesor mishaps occurred; PFP made newfriends and contacts in the Cambodianand Liberian communities; and webrought the project in on budget (well,almost). Then a hand-scrawled notefrom a sixth grader arrived, evaluatingthe camps according to a different,profoundly personal standard.“It stopped my homesickness.…”My eyes water each time I read it.—Germaine Ingram2009 Summer/Fall WIP 29