View publication (pdf file 6.5 mb) - Erik Thomsen

View publication (pdf file 6.5 mb) - Erik Thomsen

View publication (pdf file 6.5 mb) - Erik Thomsen

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1Kano School 狩 野 派Roosters and Chicken in a Ba<strong>mb</strong>oo GroveEdo Period (1615 –1868), early 17th CH 64 ¾" × W 133 ½"(164.5 cm × 339 cm) eachPair of six-panel folding screensInk, colors, gofun, gold and gold leaf on paperFrom the fourth century onwards, the Chinese depictedsages in ba<strong>mb</strong>oo groves, in seclusion fromthe world and in lofty conversation with each other. 1This tradition later transferred to Korea and Japan,where the theme, Chikurin no shichiken 竹 林 の 七 賢 ,became one of the traditional expressions of painters,for example of the Kano school, who painted itwidely on scrolls, screens and sliding doors. 2The moriage consists of round family crests (mon)on a diamond pattern. Interestingly, the gilt andchased copper hardware on the screen frame incorporatesthe same family crest design and cantherefore assumed to be the original 17th centuryhardware. Further use of moriage relief canbe seen in the three-dimensional modeling on thecocksco<strong>mb</strong>s and on the legs. The overall effect isthat of luxury, privilege and expense, an effect underlinedby the heavy use of costly mineral colors.The screens were most likely created for the year ofthe rooster by a leading sponsor of the arts, possiblyby a me<strong>mb</strong>er of the aristocracy or a daimyowarlord.In this painting we see the same theme of a gatheringin a ba<strong>mb</strong>oo grove, yet here we have a play onthe genre, with roosters and hens taking the placeof learned sages. And instead of lofty conversation,we have hens clucking to one another and to theiroffspring. While the parody of traditional themeswas not unusual—painters such as Harunobu placedcourtesans in place of the sages in their versionsof the ba<strong>mb</strong>oo grove—the depiction of chickens assages is rare.The paintings also have a seasonal element, as theartist has divided the screen pair into images ofspring and autumn. The right half shows the springwith newborn chicks, new ba<strong>mb</strong>oo sprouts andflowering Chinese clematis (Tessen 鉄 銑 , Clematisflorida), a plant blooming in late April. In contrast,the left half shows the autumn with the chicksfully grown, the ba<strong>mb</strong>oo mature and, instead ofclematis, ivy with autumn colors. The artist contrastsspring and fall, the newborn and the adult, beginningsand maturity.The screens have an intricate and finely craftedband along the top with gilt moriage patterns.This moriage was built up with layers of gofun (seashell powder) and then painted with gold wash,a phenomenon appearing in 17th century screens. 36 7

2Tosa Mitsuyoshi 土 佐 光 吉 (1539 –1613), attr.Scenes from the Tales of GenjiMomoyama Period (1568 –1615), early 17th CH 63 ½" × W 146 ½"(161.3 cm × 372.3 cm)Six-panel folding screenInk, mineral colors, gofun, silver, goldand gold leaf on paperThis important screen displays an elaborate selectionof scenes from the eleventh-century novelTales of Genji. The finely detailed figures interspersedthroughout the composition illustratescenes from different chapters of Genji, but areunified by the theme of nature, more specifically,the link between nature and the protagonists ofthe novel. Two keys to the connections are the fullmoon on the upper left and the bridge on theupper right of the screen.The full moon on the upper left refers to the romanticboat scene on a winter night in the Ukifunechapter, seen in the upper center. Here Niou isseated in the boat with Ukifune and, while lookingat the hills bathed in moon light, they pledgeundying love to each other. 1In the Asagao chapter the moon appears again asGenji and Asagao look out at the garden on a winternight and admire the fallen snow. Genji asks thepage girls to go out in the garden and roll a snowball,and he and Asagao enjoy the scene bathed inmoonlight. 2The moon connects these two scenes, which alsoshare the same season and the nocturnal setting.Central to both cases is the joy of love when lookingat nature together, specifically on a winter night.The bridge in the upper right corner refers to theUkifune love boat scene, which takes place closeto Uji Bridge. 3 The bridge is also associated with theexcursion to Sumiyoshi Shrine in the Miotsukushichapter, seen on the right. Waiting inside his carriage,Genji wants to write a love letter and his servantKoremitsu hands him a writing box and brushes. 4The curved bridge on the screen refers to bothscenes, the Uji Bridge and the Sumiyoshi Bridge;the red torii gate in front of the bridge refers tothe Sumiyoshi Shrine. Bridges with their many poeticallusions became sy<strong>mb</strong>ols for travel in naturein the literal and visual culture of the Heian andlater period. 5The last two scenes that balance the compositionon the bottom left and right corners are, on thebottom left, the emperor being presented withpheasants taken in a hunt, bringing nature to thepalace; 6 and, on the bottom right, the poignantscene from the Yomogiu chapter where PrinceGenji visits his long-lost love, the Safflower Princess,who suffers from poverty in a run-down mansion.Here Prince Genji is led by his servant Koremitsu,who guides him to the dilapidated housethrough the overgrown garden. 7In all of these scenes, we see how the figures negotiatewith nature and how nature relates to love,to imperial offerings, to travel and even to poverty.What at first seems to be a set of non-connectedscenes are in fact expertly selected moments in thenovel that connect by themes from across the panelsof the screen.The screen is attributed to Tosa Mitsuyoshi throughsimilarities in style, facial features, and goldenclouds. The golden clouds are made of two typesof gold—gold leaf bordered with gold wash ongofun—and the features of the faces are superblyexpressive. Mitsuyoshi and his atelier painted anu<strong>mb</strong>er of Genji screens during his lifetime andexamples by him exist in the Metropolitan Museumof Art in New York, the Honolulu Academy of Arts,the Kyoto National Museum and the IdemitsuMuseum of Art.12 13

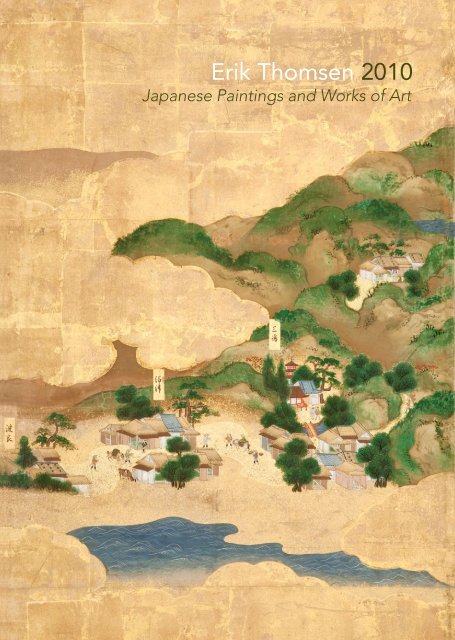

3Scenes from the Great Eastern RoadUnknown artistEdo Period (1615 –1868), circa 1800H 49 ¾" × W 117 ½"(12<strong>6.5</strong> cm × 298.5 cm) eachPair of six-panel folding screensInk, mineral colors, gofun, gold flakesand gold leaf on paperThis pair of screens presents the viewer with an excitingjourney through the imagination, without thehardship of actually traveling. We see here in greatdetail the most important road in Japan, the GreatEastern Road Tōkaidō, which connected the oldand the new capital cities of Japan. Not only are thecities and sites along the road depicted, but theartist has also added interesting events, such as processionsof daimyo warlords, street side shops,and sea travel.The route is not a straight one, but one bendingand turning along the mountains and streams. Ineffect, the route is recreating travel with all its unexpectedtwists and turns. As Constantine Vaporis recountsin his classic book on Edo-period travel, theidea of travel became a nation-wide fad from themid-Edo period onwards, and people would takelong trips in groups or individually, enjoying thesites along the way. 1 This screen was very likely createdin response to the demand for objects relatedto travel, perhaps in commission for a patron whohad traveled the route himself.From the seventeenth century onwards, Japaneseartists created woodblock prints, hand scroll paintings,screens and books on the topic of travelalong the Tōkaidō Road. In their images the artistsprovided not only information about the sites, butalso placed the road in the contexts of the famousviews of Japan, Meisho, that could be seen alongthe way. In this sumptuous pair of screens, we notonly get a sense of the long and often arduousroute of the Tōkaidō, but also see the splendidsites along the way. Artists of the time emphasizeddifferent aspects of the road; in this case, theemphasis is clearly on the remarkable castles andmountains—the greatest feats of man and nature.In contrast, the cities are here presented as an asse<strong>mb</strong>lyof simple one-story buildings—even Edo,the capital city.The road became an important topic in the cultureof mid- to late-Edo period Japan. Not only werefamous artists, such as Utamaro, Hiroshige, andHokusai making print series with connections tothe Tōkaidō Road, but literature and Kabuki dramaalso became obsessed with the idea of travel. Thecomic novel Hizakurige, for example, centers onthe adventures of two protagonists as they traveldown the Tōkaidō. 2 An important multi-volume<strong>publication</strong> in 1797, the Tōkaidō meisho zue, becamea source for later artists, such as Hiroshige,who found compositional ideas in the volumes.And of course, the most famous of all these artisticefforts was Hiroshige’s great series of woodblockprints, the Fifty-Three Stages of the Tōkaidō,published in 1833 – 34, which came to influenceall efforts afterwards. This pair of screens showsno specific traces of Hiroshige’s work, but relatesinstead to other earlier sources. 3Interestingly, some of the sites named on smalllabels along the road are not on the Tōkaidō.These sites include mountains and large castles(Mount Hiei and Zeze Castle) as well as partsfrom other views series, such as the Eight <strong>View</strong>sof Ōmi (Karasaki and Miidera) and the famousviews of Edo (Shiba Daibutsu). 4 It seems that thenames are taken from a conflation of sources:from the Tōkaidō, from famous view series, andfrom important sites that can be seen from theroad. 5 They all have in common the sense of travelwithin the imagination, experiencing all the pleasuresand serendipitous discoveries of travel whilein the comforts of one’s own home.16 17

4Araki Kampo 荒 木 寛 畆 (1831–1915)Peacock Pair by CliffsMeiji period (1868 –1912), dated 1907H 76 ¾" × W 75 ¾"(195 cm × 192.4 cm)Two-panel folding screenInk, colors, gold and gold-leaf on silkSignature:Kampo 寛 畆Seals:1) »Seventy-seven year old Kampo« 七 十 七 翁 寛 畆2) »Artist name Tatsuan« 號 達 庵A majestic peacock stands on top of a craggy cliffand surveys the world around him, while his matewalks below, in the safety of his alert gaze. Thepainting was made by one of the great artists ofmodernizing Japan at the age of seventy-seven.Despite his advanced age, we sense the strengthof the artist in the dramatic brushstrokes, the clearsense of composition, and the finely delineatedtechniques. Just like the male peacock, he still verymuch rules his corner of the world.Kampo was born in Edo and started to work at anearly age as apprentice for the Araki workshop,where he showed early promise. He was eventuallyadopted into the Araki family at the age of twentytwoand became its head painter. At one time heattempted oil paintings, but eventually returned tothe Nihonga school style. Kampo specialized inpaintings of flowers and birds. He unified the variousstyles and introduced new influences and techniquesfrom the West, and taught a generation ofyoung artists, becoming an important pioneer of thenew age of painting in Meiji Japan.Remarkably, Kampo had extensive success outsideof Japan and became one of the most famousJapanese artists in the West. He entered works andwon numerous prizes at international expositions,such as Vienna in 1872, Chicago in 1893, Paris in1900, St. Louis in 1904, and London in 1910. Hewas also the first Japanese artist to become ame<strong>mb</strong>er of the prestigious Royal Society of Arts inLondon. Inside Japan, he was very active in nationalexhibitions and won numerous honors. 2 Hetaught at the Tokyo Art School from 1898 to 1908and at other universities as well. The present screenstems from the time he was teaching at the TokyoArt School.The sumptuousness and vitality of the peacock arereflected in the rich gold-leaf ground and in thefine details Kampo added with gold wash on topof the ink. He also added light colors to give depthto the plumage of the birds and drew the rocksand the ba<strong>mb</strong>oo with an array of textured strokesand ink wash techniques. In all these aspects, thepainter goes back to a long tradition of peacockpaintings on gold ground, such as those createdby the Maruyama and Kishi Schools. 122 23

5Usumi Kihō 内 海 輝 邦 (b. 1873)The Raven and the PeacockTaishō Period (1912 – 26), circa 1920H 69" × W 136 ¼"(175 cm × 346 cm) eachPair of six-panel folding screensInk, mineral colors, gofun, gold, silver,lacquer and silver leaf on paperSignature: Kihō 輝 邦 , Seal: Hiroaki 廣 精its black feathers covered with powders of lapislazuli, its legs highlighted in lacquer, and its eyeswith gold. The face of the raven is finely modeledwith masterfully modulated ink wash on its beak,giving a three-dimensional effect. The heavy useof expensive mineral colors indicates that Usumimade the screen pair for an important occasion,possibly a national art exhibition.The artist presents the viewer with a remarkablecomposition of a raven and a peacock in conversationacross two large six-panel screens. The positioningof the two birds at first startles through thestrong contrasts: the smaller jet-black raven onthe right and the large proud peacock with its fullshow of polychrome feathers on the left.What exactly was the intent of the artist in this strikingjuxtaposition? He may have intended to showthe animals as an episode from Aesop’s fable, thestory of the crow and the peacock. The narrative,however, remains unclear: did the covetous crowattempt to steal a feather and dropped it, discoveredby the angry peacock? Or is the peacockbragging, showing off its rich display, while theraven is looking on in envy? Although the messageis uncertain, the dramatic dialogue is clear. A keyaspect of this dialogue is of course the contrastbetween the large colorful bird and the seemingly—until examined closer—drab black bird.The screen is remarkable for another reason, itstour-de-force display of materials and techniques.Usumi painted the silver-leaf surface with luxuriousmaterials, including gold, silver, lacquer andground malachite, lapis lazuli and gofun. Thepeacock is composed with a densely inter-woventexture of feathers i<strong>mb</strong>edded with thick layers ofgold and mineral colors, including malachite andlapis lazuli. The bright eye is painted with gold,the beak with silver, and the head and body aremolded with relief details using gofun. The drablookingraven is in fact sumptuously created, withUsumi Kihō was a skilled painter of great promise.He was born in Matsue in Shimane Prefectureby the Japan Sea in 1873 and managed to gainacceptance to the highly competitive Tokyo ArtSchool, presently the Tokyo University of the Arts,at a key time in its history. The university had beenfounded a few years earlier and was run by thegreat artist Hashimoto Gahō 橋 本 雅 邦 (1835 –1908).Kihō became a student of Gahō 1 and learned inthe company of a select group of the future greatartists of Japan. A list of his fellow students at thetime reads like a who’s who of the great Taishō andShōwa period artists: Yokoyama Taikan 横 山 大 観 ,Shimomura Kanzan 下 村 寒 山 , Hishida Shunsō 菱 田春 草 , Kawai Gyokudō 川 合 玉 堂 , among others.During his years at the Tokyo Art School Kihō createdthree works that were thought importantenough to store at the university museum. 2 Upongraduation in 1893, Kihō accepted a position atthe Fukushima Middle School in Fukushima Prefecture,teaching art. Among his colleagues at theschool was the great scholar Tsunoda Ryūsaku 角 田柳 作 (1877 –1964), who eventually became knownas the "father of Japanese studies" at Colu<strong>mb</strong>ia University3 During their time there together (Ryūsakutaught at the school 1903 – 8), the two collaboratedon projects.We see traces of Usumi’s activities through the 1910sand 1920s of the Taishō period, when he movedback to Tokyo and became an established artist inthe capital city. 4 The present work stems from hisperiod of activity in Tokyo.26 27

6Hirai Baisen 平 井 楳 仙 (1889 –1969)Chinese Landscape with PagodaTaishō Period (1912 – 26), 1925H 68" × W 74 ¾"(173 cm × 189.7 cm)Two-panel folding screenInk and colors on paperSignature: Baisen 楳 仙Seal: »Painted by Hirai Baisen« 比 羅 居 白 仙 画A series of perpendicular cliffs, precipitous gorgesand towering temple pagodas gives this remarkablelandscape painting a sense of peril and exoticism.The setting is not Japan: this painting stemsfrom Hirai Baisen’s Chinese phase, a period that heentered after his travel to China in 1913. Here is apainting with rough strokes of ink on paper in theold tradition of depicting Chinese scenes, a traditionthat goes back to Sesshū (1420 –1506).We see the artist’s great skill in his use of ink. Notonly does he use ink in many modalities, varyingfrom intense black to faint grey, but he also variesthe wetness of the brush, creating a misty feel tothe vegetation, as some sections are vague whileothers are in sharp focus, lending to an atmosphereof misty mountain peaks. We also see a greatvariety in brush patterns, with some brushes roughand hard-bristled; Baisen uses these repeatedlyto get a sense of wild vegetation on the cliff sides.Another indication of his love for experimentationcan be found in the special paper he used for thiswork: both sides of the screen are painted on asingle large, custom-made sheet of paper, whichis unusual for this scale of work.Baisen has used colors sparingly with carefuldeliberation. To the landscape he added a wellbalanced,faint application of red-brown colors.These colors impart an autumnal feel to the sceneand at the same time create a color palette thatis exotic—it is after all not a scene from Japan, butone from a foreign, yet familiar, culture that Baisenportrays. The light blue color used in one spot, onthe coat edge of the single Chinese traveler, addsan exotic touch.A nu<strong>mb</strong>er of other examples exist from the artist’speriod of intense immersion into Chinese expressiveness.For example, a pair of six-panel screensin the Honolulu Academy of Arts displays the samekind of composition and textual strokes. 1 Here, too,we see a towering pagoda in the distance over ravinesand a precipitous landscape. What differentiatesthe two works from each other is that the Honoluluscreens are solely expressed in ink, whereasin the present work we see his experiment with colorsand a more complex composition.The screen was created in 1925 when Baisen waspreparing a series of screens with ink paintingsof Chinese landscapes for the sixth Teiten exhibitionof 1925. Two other sets of the screens createdduring this burst of energy have recently beenpublished. 2Baisen is a painter of many styles who succeeds insurprising at every turn. 3 A look at another paintingby him in this <strong>publication</strong> item15, (a snow sceneof the Kamogawa River dated to 1917) shows howgreatly his style changed over a few years. Constantis his technical excellence and his fascination withvarious materials and tools: the brushes, the paints,and the surfaces. We see him forever experimentingwith new ideas. He was clearly an intellectualpainter at the cutting edge of the twentieth-centuryNihonga movements during his early years. 4 Thescreens are a testament to the genius of Baisen ashe revisits the iconic masterpieces of the past andsuccessfully reworks them into a new vocabulary ofhis own.32 33

7Nakatsuka Issan 中 塚 一 杉 (b. 1892)Morning Quiet あさしづShōwa Period (1926 – 89), 1927H 70 ½" × W 90"(179.3 cm × 228.6 cm)Two-panel folding screenInk, colors and gofun on silkSignature: Issan ga 一 杉 画 »Painted by Issan«Seal: Nakatsuka 中 塚Exhibited: The 8th Teiten National Exhibition, 1927Published: Nittenshi 日 展 史 , vol 8, p. 117, nr. 181.The artist Issan presents us with an intimate sceneof a small vegetable garden in the early morningquiet. It is early morning in summer, the lower partof the painting still dark and soft light and bluesky starting to appear above.We see a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of plants and vegetables in acomposition of compressed rows. In the front areflowering garden balsam (Hōsenka 鳳 仙 花 ) andthree pepper plants (Shishitōgarashi 獅 子 唐 辛 子 ).In the next row are four eggplants (Nasu 茄 子 ),followed by a row of cucu<strong>mb</strong>er plants (Kyūri 胡 瓜 ).In the far background are the ink outlines of youngba<strong>mb</strong>oo plants. The various plants with their differentcolors, leaves, fruits and flowers interweave onthe painting surface, creating a densely interrelatedidyllic vision. A hint of humor can be seen with thepatch of weeds in the front right and with the morningglory on the far right which comes out to greetthe artist’s signature.Looking closer, one notices four insects hiddenamong the leaves: a praying mantis, a dragonflyand two grasshoppers. The artist also chose toshow natural decay in the work: many leaves areinsect-bitten, and a fallen-down cucu<strong>mb</strong>er and severalleaves are in various stages of decomposition.This undertone of decay and death is contrastedby the vitality of the strong colors of eggplants andtheir leaves.Issan uses special effects, such as gofun, a whitepowder made from sea shells, which he appliedbelow the paint on the cucu<strong>mb</strong>ers to give themmoriage three-dimensional effects. Throughout thepainting, the line is always under control; the dragonflybalanced on the cucu<strong>mb</strong>er leaf, for example, isdrawn in a poetry of ink lines.The work is a remarkable achievement for theyoung artist and was the first of his to be acceptedfor a national exhibition, the 8th Teiten Exhibitionin Shōwa 2 1927, shown under the title あさしづ orMorning Quiet and illustrated in the accompanyingcatalog. 1 Born in 1892, Issan studied under twogiants in the Kyoto art world of the time: TakeuchiSeihō 竹 内 栖 鳳 (1864 –1942) and Nishimura Goun西 村 五 雲 (1877 –1938). 2 After his apprenticeship,he settled in the Shimogamo area of Kyoto and exhibitedat a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of prestigious national exhibitions:he entered works in five Teiten exhibitions,three Shin-Bunten exhibitions, one Nitten exhibition,among others. 3 The last trace we have of the painteris his entry in the ninth Nitten exhibition of 1953.Interestingly, Issan must have been fond of the vegetablegarden theme, as he returned to it ten yearslater in a work labeled »Vegetable Garden in EarlyAutumn« 菜 園 初 秋 for his entry into the first Shin-Bunten exhibition of 1937. The famous cultural figureOguma Hideo 小 熊 秀 雄 (1901– 40) saw this workat the exhibition and wrote the following praiseabout Issan’s screen: 4 »An outstanding characteristicof present-day Nihonga painting is the ability todraw an inherently complex image of a vegetablegarden clearly without any confusion.« The skillthat was apparent in Issan’s later work of 1937 iscertainly also clear in this superb screen that Issanpainted ten years earlier.36 37

8Nakatsuka Issan 中 塚 一 杉 (b. 1892)Flowering YamabukiShōwa Period (1926 – 89), circa 1930H 78 ¼" × W 82"(199 cm × 208 cm)Two-panel folding screenInk, colors and gofun on silkSignature: Issan saku 一 杉 作 »Made by Issan«Seal: Nakatsuka 中 塚As with the other screen by Issan in the presentcatalog, the previous entry entitled »MorningQuiet«, we see here a close observation of naturewithin an intimate garden setting.The artist presents the viewer with a scene fromspring, from a warm sunny day in the second halfof April. Dominating the scene over most of thepainted surface is a Japanese Yellow Rose (Yamabuki山 吹 Kerria japonica) which flowers in majesticbeauty by an old ba<strong>mb</strong>oo fence. Meanwhile to theright a white Japanese peony (Yama Shakuyaku山 芍 薬 Paeonia japonica) blooms and below it,through a crack in the fence, we see another whiteflowering plant. In the upper corners is a floweringmaple tree. Standing above the central Yamabukiis a tall cherry tree, now past its point of glory withits few remaining petals and many new leaves.On the bottom left from the ground the artist hasdepicted a winding ivy cli<strong>mb</strong>ing up the brokenfence. In the middle of this maze of blossomsand leaves sits a solitary Lidth’s Jay (Ruri Kakesu瑠 璃 懸 巣 Garrulus lidthi), its blue feathers forminga focal point and contrast to the yellows andgreens of the painting.Much time, expertise and expense went into creatingthis work, and judging from its over-sized format, itwas most likely a shuppin-saku, made to be exhibitedat one of the major art exhibitions of the time. Inthe complex composition we see exquisite detailsin the fine lines on the flowers and ba<strong>mb</strong>oo fence,and in the raised moriage areas on the yellow rose,the peony flowers, and the cherry blossoms, whichwere created with gofun or seashell powder. Thebark of the cherry tree is especially remarkable forits three-dimensional feel and realistic moriage texture.The mounts are custom-made for the screen,using luxurious shibuichi 1 metal with a perforatedsukashi design of cherry petals.Issan studied under two of the greatest draftsmen inthe history of the modern Kyoto art world: TakeuchiSeihō 竹 内 栖 鳳 (1864 –1942) and Nishimura Goun西 村 五 雲 (1877 –1938). After his studies he settledin Kyoto as an independent artist and submitted regularlyto the important national exhibitions over thenext decades, the last being the Nitten in 1953. 2As with Issan’s other work »Morning Quiet«, wesee here a tension between youth and decay,between the vibrant yellow colors of the brilliantYamabuki on the one hand and the deteriorating,stained old ba<strong>mb</strong>oo fence on the other. The fallenpetals and wilting leaves on the ground also serveas a contrast to the blooming Yamabuki above.40 41

9Sōju 双 樹 (ac. Taishō Period)Sea Gulls by the SeashoreTaishō Period (1912 – 26), 1920sH 69 ¼" × W 68 ¾"(175.8 cm × 174.8 cm)Two-panel folding screenInk, colors, gofun and silver on paper.Signature: Sōju 双 樹Seal:Sō 双In this striking composition, we see two seagullson the seashore, seemingly overwhelmed by theincoming waves. The painting is a fascinating studyof movement and patterns that spread across itssurface.screen dates from the innovative period of theearly 1920s. The Taishō period was noted for agreat flowering of the arts, with a proliferation ofart schools and the education of great many skilledstudents. Unfortunately for them (and for us) theperiod was also known for its great disasters: theKantō Earthquake of 1923, the global economiccrash of 1929 and the resulting depression thatchanged the future for a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of promisingartists in a decidedly negative way, sometimes withcatastrophic effect. 1 Much research remains to bedone about artists of this period, including the identityand biography of the artist who created thismasterpiece.Not only is the screen remarkable for its daringcomposition, but also for its display of technicalability. For one thing, this painting is a masterpiecein the use of gofun, or seashell powder. Althoughgofun has been used by Japanese artists for centuries,its use rarely reaches the level of technicalperfection seen in this screen. We can see extensiveuse of gofun on the waves and on the bodies ofthe gulls, which thereby achieve a tactile threedimensionalfeel. Detailed use of the material canbe seen on the seagull at the back, for example,where a wave of white gofun faintly washes overits left foot.Another technical element is the sophisticated useof sprinkled silver flakes, which can be seen notonly on the beach, simulating the wet sand sparklingin the sunlight, but also under the layers of gofunwaves,where it mimics reflecting sand under water.The artist has also darkened the rim of sand directlybordering the incoming waves, cleverly giving animpression of water-logged sand.As for the artist, research still remains to be done.Little is known, beyond the evidence of the screenitself. Judging from the style, we know that it musthave been a Nihonga artist with great talent. Andjudging from similar objects, we can say that the44 45

Paintings

10Hakuin Ekaku 白 隠 慧 鶴 (1685 –1768)The Second Patriarch Standing in the SnowEdo period (1615 –1868), circa 1725H 32 ¼" × W 11¼" (incl. mounting 65" × 15 ¾")(82 cm × 28.3 cm, 165 cm × 40 cm)Hanging scroll, ink on paperInscription:二 祖 昔 寒 夜終 夜 立 雪 庭 積雪 埋 腰 初 祖 見呵 口 諸 佛 無 上 少 道曠 却 難 行 難 忍能 忍 難 行 能 行 汝等 憍 心 慢 心 争 豈得 分 二 祖 即 断 左 臂見 今 時 認 無 事 安 閑為 向 上 禅 認 無 念 無 心為 宗 票 視 瞎 癡 漢將 喜 耶 將 悲 耶 嗟Translation:A long time ago, the Second Patriarch stood in agarden on a cold night until the snow came up tohis waist. The First Patriarch saw this and scoldedhim: »It's wasteful for you to approach the marvelousways of the Buddhas with worthless efforts.Can you endure that which cannot be endured, andpractice that which cannot be practiced? How canyou hope to know true religion with a shallow heartand an arrogant mind?«The Second Patriarch then cut off his left arm. Seeingthis, Bodhidharma immediately allowed Huikeaccess to peaceful tranquility, and let him practicean advanced level of Zen. Allowing freedom fromideas and feelings, the Second Patriarch practicedthe true nature of religion and came to understandthe blind and the stupid.On one hand, rejoice! On the other, how sad!Seals:1) Hakuin 白 隠2) Ekaku 慧 鶴3) Kokan’i 顧 鑑 意Box inscription, outer:»True (Ink) Traces of Zen Master Hakuin: TheSecond Zen Patriarch« 白 隠 禅 師 真 蹟 二 祖Box inscription, inner:»Certified by the old monk Sōkaku, presently atthe Shōin[ji] Temple, dated on an auspicious dayin the 2nd month of 1960«昭 和 三 十 五 年 如 月 吉 日 現 松 蔭 宗 鶴 翁 識Box inscriptions, end:»Hakuin: Niso inscription, apprentice monk insnow. Bokubi« 白 隠 二 祖 賛 雪 中 雲 水 墨 美»Hakuin Zen Monk: painting and inscription ofDharma Master Niso« 白 隠 禅 師 二 祖 大 師 画 賛Oval seal mark: »Shinwa’an Collection« sealPublished in:Morita, Shiryū 森 田 子 龍 , ed. Bokubi Tokushū:Hakuin bokuseki 墨 美 特 集 ― 白 隠 墨 蹟 .Kyoto:Bokubisha 墨 美 社 , 1985, plate 263.Tanaka Daisaburō 田 中 大 三 郎 , ed. Hakuin zenshibokusekishu 白 隠 禅 師 墨 蹟 集 . Tokyo: RokugeiShobō 六 芸 書 房 , 2006, plate 47Hakuin here represents the Second Patriarch of ZenBuddhism, Eka 慧 可 (Chinese: Huike; 487 – 593), ashe is standing out in the snow, patiently hoping forthe First Patriarch, the great Bodhdharma (Japanese:Daruma), to accept him as a student. We see thesnow piling up on the monk’s hat and on the pinesin the background and feel the hardship of the monkhoping for approval from the stern Indian monk,sitting in meditation in the Shaolin Temple 少 林 寺 .According to the records, Eka was born close toLuoyang 洛 陽 and practiced religions under anu<strong>mb</strong>er of masters before coming to the snowygarden at age forty. The famous story alluded to inHakuin’s inscription describes how the monk wasfinally able to receive Bodhidharma’s approval bycutting off his left hand and presenting this as a50

tribute to the older monk. After several years ofhard practice, Eka received the Dharma transmissionfrom Bodhidharma. During the lifetime ofEka, Buddhism suffered under persecutions in China.Nonetheless, he is recorded as having preachedfor over forty years and coming to rest at the highage of 107.The earliest extant biographies of Zen Patriarchs isthe Biographies of Eminent Monks (519) ( 高 僧 傳 ;Japanese: Kōsōden; Chinese: Gaoseng zhuan) andits sequel, Further Biographies of Eminent Monks( 続 高 僧 傳 ; Japanese: Zoku Kōsōden; Chinese: Xugaoseng zhuan), written in 645 by Daoxuan ( 道 宣 ;596 – 667). For the Japanese monks, however, thefourteenth-century compilation Transmission ofthe Lamp ( 伝 灯 録 ; Dentōroku), by Keizan Jokin(1268 –1325), a collection of 53 enlightenment storiesbased on the traditional legendary accounts ofthe Zen transmission between successive mastersand disciples, became very influential. 1 Althoughthe stories are semi-legendary, they came to takeon real importance for the early modern Japanesemonks, such as Hakuin. 2 Although Hakuin’s inscriptionquotes sections of the Transmission of the Lamp,there are sections that do not appear there or inother known texts. As all of Hakuin’s Second Patriarchpaintings have variations in the text, it seemssafe to say that Hakuin worked from memory andadded or amended sections as he saw fit.Many portraits of Zen patriarchs by Hakuin exist,and he is famous for his images of the Bodhidharmaand of the Kannon, which comprise the largestgroup of extant Hakuin paintings. There are, however,very few paintings of the Second Patriarch. 3 Accordingto the great Hakuin scholar Takeuchi Naoji竹 内 尚 次 , the portraits of the Second Patriarch areimportant as a representation of Hakuin’s earliestextant paintings—he suggests that a painting similarto the present work was brushed by Hakuin in histhirty-fifth year. 4 Moreover, Takeuchi provides noexamples of Second Patriarch paintings brushedafter the earliest period of painting. 5 This makesthe Second Patriarch paintings rare, as Hakuinclaimed to have burned all his earlier paintings.Furthermore, it could well be significant that Hakuinonly painted the Second patriarch painting in hisyounger days, at a time when he was still strugglingwith the principles of Zen Buddhism. At times hesurely must have felt like the Second Patriarch himself.And as he writes in his inscription (»On one hand,rejoice! On the other, how sad!«), Hakuin seems notentirely at ease with the message of extreme selfmutilationthat the story valorizes. Perhaps he wasable to separate himself from the pressing messageof the story of the arm-sacrificing monk as hegot older and more settled into Zen practice.The painting is also of interest in the way it showsHakuin, the painter, working with shapes. Lookingat the composition, one can see a carefully orchestratedsemi-circle of triangular shapes, startingwith the monk’s hat in front and repeating with pinetrees behind. The receding line of similar shapesworks to anchor the monk firmly into the compositionof this painting and further emphasizes thekey point of the story: the permanence, duration,and perseverance of the monk as he stands rootedto the garden ground over night while the snowpiles up around him. It is a fine example of howa painting’s composition reinforces its motif. It alsoreminds us that the often haphazard-looking appearanceof Hakuin paintings might well be anythingbut spontaneous: the compositions are likelythe result of much consideration of shapes andpainterly ideas.The painting is housed in a kiri box that was certifiedand inscribed in February 1960 by the Hakuinauthority Tsūzan Sōkaku (1891–1974), the seventeenthabbot of Hakuin’s old temple, the ShōinjiTemple in Hara.52

11Hakuin Ekaku 白 隠 慧 鶴 (1685 –1768)Tenjin Traveling to ChinaEdo period (1615 –1868), circa 1760H 15 ¾" × W 5 ½" (incl. mounting 41¼" × 8 ¼")(39.9 cm × 13.8 cm, 104.5 cm × 21 cm)Hanging scroll, ink on paperInscription:唐 衣 おらで 北 野 の 神 ぞとは袖 にもちたる 梅 にても 知 れEven if you cannot tellFrom the Chinese robes he wearsYou must know that it is himFrom the plum blossomsHe holds in his sleevesFigure composed of characters:南 無 天 満 大 自 在 天 神Hail to Tenjin, God of the Tenman ShrineSeals:Hakuin 白 隠Ekaku 慧 鶴Kokan’e 顧 鑑 夷This whimsical ink painting by Hakuin is of SugawaraMichizane 菅 原 道 真 (845 – 903), a historicalfigure about whom many legends have been created.Michizane was an aristocrat and courtier atthe imperial palace in Kyoto and became a leadingscholar and poet of his generation. After beingfalsely accused by a political rival, he was exiledto Dazaifu in Kyushu, where he died in great sorrow.The legends have him come back later to the capitalcity as a malevolent ghost and cause greathavoc until the Kitano Tenmangū Shrine was builtin his honor. Eventually his court titles and honorswere restored and he was deified as a Shinto godby the Heian leaders in an attempt to calm hisangry spirit. 1As a god, Michizane took on the function of theGod of Learning and received the blossomingplum flower as his sy<strong>mb</strong>ol. Hakuin painted manyimages of Michizane and seems to have beenfond of this gentle figure of learning and culture. 2It seems fitting that the God of Learning is heredrawn entirely in characters—in the so called mojie文 字 絵 »character painting« technique. 3The inscription is from a 13th century Japanese textin which the spirit of Michizane flies across timeand space and actively interacts with leading Buddhistmonks in Japan and China, more than 300years after his death. 4 In this legend, he first appearsin 1241 in the dream of a Kyushu merchantand asks for a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of ceremonies in his honor.Despite valiant attempts by the rich merchant,they fail to satisfy Michizane,who decides to makean appearance before the Tofukuji Temple abbotEnni Benen 円 爾 弁 円 (1202 – 80) in Kyoto and askto become his student. Enni instructs Michizane togo instead to China and to seek guidance from thegreat monk Wuzhun Shifan 無 準 師 範 (1178 –249),who was Enni’s own master. Michizane follows theadvice and travels to China in a single night toappear before the Chinese monk and the two thenhold a conversation, which includes an exchangeof poetry. This journey by Michizane to Chinaforms the title of this painting. A poem uttered byMichizane is the one that Hakuin inscribed abovethe painting. During the conversation, the Chinesemonk gives Michizane a Chinese robe as a sign ofenlightenment, a robe that Michizane takes backwith him to Japan. Hakuin here depicts Michizanewith the Chinese robe that he has just receivedfrom Wuzhun Shifan.The painting is interesting on a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of points,as it represents interactions between religionsand cultures, between images and words. TheMichizane painting can be seen as a sy<strong>mb</strong>olicinteraction between China and Japan (in people,in clothing, in travel, and in text) and between54

eligions (a Shinto god interacting with Buddhistleaders and receiving enlightenment). We alsosee the creative interaction between words andimages, as the clothing of Michizane is composedof individual characters, forming the words »Hail toTenjin, God of the Tenman Shrine.« The charactersare not written in order, but instead randomly followthe contours of Michizane’s clothing and body.The artist is mischievously playing a game with theviewer and challenging him to solve the reading ofthe visual puzzle.We see Hakuin in this and other similar paintingsnot as a strict promoter of his own sect, but ratheras a teacher who understands and appreciates differences—assomeone who reaches across dividesbetween cultures, religions and traditions.56

12Sengai Gibon 仙 厓 義 梵 (1750 –1837)The Hakata Top Crossing a StringEdo period (1615 –1868), circa 1820H 14 ¼" × W 21½" (incl. mounting 49 ½" × 24 ¾")(36.3 cm × 54.7 cm, 126 cm × 62.6 cm)Hanging scroll, ink on silkSeal on painting: Sengai 仙 厓Painting inscription: Ladies and gentlemen, if youare looking for wealth and fortune, then look at thespinning top from Hakata, actually crossing a string.Careful, careful! Look here, if you lower the stringthen it will come spinning, spinning toward you. Ifyou raise it a little, then it will go spinning away, allthe way to the next town. So be careful of how youhold your string. Why don’t you try?東 西 々々 福 徳 を 願 ふ / なら 博 多 古 まの / 糸 渡 りアレ々々手 元 を / さくれハこちらへ / ころ々々ころんてこさる /手 元 を 少 高 むれハ / 向 ふ 町 へさけて 行 / 手 元 におきを 付 られませ / ヨウ々々Box, outer inscription, top: »Brushed by the MonkSengai. Painting with Inscription of the Hakata TopCrossing a String« Hakata koma ito watari no gasan:Sengai oshō hitsu 博 多 古 満 糸 渡 りの 画 賛 仙 厓 和 尚 筆1Box, inner inscription:»Title inscribed by the 70-year old Tōkō«shichijū-ō Tōkō dai shirusu 七 十 翁 韜 光 題 署We see here a strikingly humorous ink painting bySengai, one of the great Edo period Zen Buddhistartists. 2 Sengai depicts a street performer who balancesa spinning top for an audience. The performer,the God of Luck Daikoku in disguise, balances thetop on a string which is tied to bales of rice—a referenceto wealth in a time when wealth was generallymeasured in nu<strong>mb</strong>er of rice bales. There is also alarge bag under the top, referring to the riches thatmay be available with luck.The joke here is how the important matter of fortunein life can be reduced to a spinning top plied by astreet performer. The strangeness of the situation isfurther reinforced by the colloquial banter of thestreet performer, as he tries to gather a crowd (seeinscription). Of course, Sengai provides a seriousedge to his joke: just as a slight movement to thehand can make the difference between the top arriving(good luck) and the top flying away (bad luck),our lives and fortunes are also easily influencedby outside events. That is why we need to place ourfaith in permanent, immovable things, such as theBuddha.Sengai made a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of paintings of street performersin order to illustrate his allegories. 3 Hewas clearly interested in the life of the commonersaround him and saw the humor in daily life as aneffective way to make his serious points about life,religion and fate to the people who visited histemple. The fact that this painting is done on silk,a rare material for Sengai, indicates that it wasmade not for a common visitor but for an importantperson. For Sengai the mixture of elite and commonwas entirely in character—in his paintings heaimed at the common human condition of all, regardlessof social status. 4Other examples of the spinning top performer areknown. One example with a similar inscription is inthe Idemitsu Collection 5 , a work that toured Europein one of the pioneering Edo-period Zen paintingexhibitions in 1964. 6 Other examples show similarcompositions, yet never exactly the same inscriptionand Sengai was apparently happy to keep changingthe wording of his message. 7The box is inscribed and authenticated by the ZenBuddhist abbot Tōkō Genjō. After a longer time ofinactivity, Sengai’s old temple, the Shōfukuji 聖 福 寺 ,was revitalized by Tōkō. He was also active as a collectorof Sengai paintings. He became known as theleading connoisseur of Sengai, and scrolls withhis inscriptions are eagerly sought after by Sengaicollectors. 858

13Kishi Chōzen 岸 長 善(fl. 1st half of 19th century)Fire in EdoEdo period (1615 –1868), circa 1845H 50 ¾" × W 23 ¾" (incl. mounting 89 ¼" × 29")(128.8 cm × 60.1 cm, 227 cm × 73.7 cm)Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on paperTop seal: Kishi 岸Bottom seal: Chōzen 長 善Box inscription: »Shadow painting of a conflagration;night scene of Edo« 影 絵 火 災 江 戸 夜 景During the Edo period, Edo became so famous forits frequent fires (and fights) that it became popularto say that: »Fire and Fistfights are the Flowers ofEdo«, 火 事 と 喧 嘩 は 江 戸 の 花With frequent earthquakes and architecture of woodand paper, fires were major events in the life of anyearly modern Japanese city. None as much as Edo,however, whose history is punctuated with majorfires that razed large parts of the city, no less than49 major fires during the Edo Period. 1In this rare and important painting we stand witnessto another major fire in its early stages. What at firstappears to be a painting of the city at dawn is in facta night scene with a fire in the distance. Upon seeingthe running figures and riders on horses headingtoward the fire, the viewer starts to understandthe setting. The groups of firefighters and other citizensscurry about with lanterns in the darkness, someclearly worried and yet others largely unconcernedwith the approaching fire.The painter of this scene was very careful with details:we are in the center of the city with the EdoBridge to the middle-right edge of the painting.Further to the right, off the painting surface, is NihonBridge and the area with the merchant warehousesof Edo. Three of these large warehouses can be seento the left of the bridge, facing the river. From theforeground to the far distance we see a multitudeof fire towers with people on top, keeping an eyeon the fire. The fire and great clouds of smoke canbe seen in the center, in the direction of Aoyamaand the southwestern part of Edo. 2A nu<strong>mb</strong>er of Japanese paintings, for example emakimononarrative hand scrolls, woodblock prints,books or paintings, show depictions of fire—andfire was also a major topic in literature and drama.Urban legends, such as the one about Yaoya noOshichi setting Edo afire to meet her belovedmonk, became one of many stories around whichKabuki and Bunraku plays were created. A wholeculture of fire and firefighters developed in Edoand much attention was given to the legend andmaterial culture of fire. It is not surprising that fireshould capture the imagination of so many, whenso much was at stake, even the lives of the citizens.Among the large groups of people gathering inshadows are me<strong>mb</strong>ers of different professionsand social groups. The largest of these are the firefighters. They hold the tools of their profession—banners, pikes and ladders—and are directed bycity ward officials (machi bugyō) on horses withlanterns. Through this crowd scene, we can see howthey have gathered, coming out of various buildingsand meeting in different groups, each withdistinct banners. The firefighters were divided byname and area and were fiercely loyal to theirgroup, working independently, sometimes in conflictwith other groups. 3The drama of the fire and the firefighters heightensupon coming closer to the fire. We see how thegroups of firefighters with lanterns crowd acrossthe Edo Bridge and onto the other shore. Furtheron, we see how they have cli<strong>mb</strong>ed up on the roofsof the houses right next to the fire, busily dismantlinghouses and their tile roofs. The fires of Edowere not fought with water; rather, houses aroundthe blaze were razed, creating natural fire barriers.60

The artist was clearly interested in the inner networksof the city and delighted in his ability to depict asmuch information as possible through shadows.This he does in a remarkably complex way. We seethe different professions: geisha (elaborate hairdecorations), samurai (two swords), blind masseurs,itinerant monks, porters, prostitutes, palanquincarriers, travelers, guides, merchants, waitressesand even two dogs. The lanterns are likewisedifferentiated, with the marks of daimyo, temples,firefighter groups, restaurants, and food vendors.The artist seems to have had a soft spot for eatingestablishments, as we see them in grand detail,from a fine two-storied restaurant in the middle(the Iroha いろは establishment) to a ramen noodleshop and other eating stalls in the center. Restaurantswere at the time not only places to eat, butwere also places to gather for entertainment or othercultural activities, such as poetry groups or salesof art, and they frequently became the subjectmatter for paintings or prints. 4 This painting showsan unusual example of a high-class restaurant infull operation against the approaching inferno onthe horizon. 5The prodigious amount of information conveyed byshadows reflects a strong interest in the tradition ofshadow pictures. These types of shadow paintings,or kage-e 影 絵 became popular during the 18th and19th centuries and appear in a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of permutations,including early woodblock prints by ToriiKiyonaga (1799), Dutch shadow prints by JippenshaIkku (1810), parlor game prints of Hiroshige from1842, and death portraits by Shibata Zeshin (1867). 7The artist Kishi Chōzen is presently unidentified, butthis may be due to a nu<strong>mb</strong>er of factors, includingthe possible need for anonymity in describing withgreat detail a scene that led to great destruction.Possible candidates are lesser-known me<strong>mb</strong>ers ofthe Kishi painting school, or a talented monk affiliatedwith the temple Chōzenji 長 善 寺8in Edo. Anotherpossibility is Chisen Daigu 智 仙 大 愚 (ac. mid19th century), a poet in the Yanaka 谷 中 district ofEdo. He was active in the cultural circles of Edo inthe mid-nineteenth century and went by the nameof Chōzen 長 善 . 9 In any case, the artist certainly hadgreat talent and familiarity with the organizationswithin the city, especially that of its firefighters: thedetails are remarkable, and the skill undeniable.We also get an indication of how a later owner ofthe painting placed great value on this rare paintingby mounting the painting in rare imported stenciledcotton textile that was likely brought to Japanby Dutch traders in Dejima.Another aspect of Edo food culture can be seenin the booths of soba sellers in the center and thevery bottom of the painting. Both of the soba sellersare labeled Nihachi 二 八 and are thus the sameestablishment. The »Nihachi« also refers to a specialkind of soba (called the Nihachi) that was introducedin 1716 and became enormously popularin Edo during the mid- and late Edo period. 6 Thesoba was made on the spot and served hot, in factwhat we can see happening in the painting.62

14Mochizuki Gyokusen 望 月 玉 泉(1834 –1913)WaterfallMeiji Period (1868 –1912), circa 1900H 65 ½" × W 22 ½" (incl. mounting 92 ¾" × 28 ¼")(166.3 cm × 56.4 cm, 235.5 cm × 71.8 cm)Hanging scroll, ink and silver on silkSignature: »painted by Gyokusen« 玉 泉 写Seal: Shiseikan 資 清 館A thunderous waterfall crashes down onto rocksin this masterful display of natural forces. An encyclopedicarray of ink techniques come togetherto create a powerful, yet poetic evocation of a massivewaterfall in action. Through the mist, sprayand streams, we see here all the permutations ofa waterfall in one great image.Gyokusen uses the tarashikomi technique of drippingink into wet ink, creating a mottled effect onthe rocks. He sprays tiny ink droplets on the silksurface and paints water splashes to portray theviolent energy of water crashing onto sheer rock.His use of fine silver droplets to simulate glisteningwater mist in the sunlight is rare and striking. Bygradually shrouding details in mist as one goesdown the waterfall, the artist has generated a clearcontrast between the darkly-modulated and cleardetails at the top of the paining and the misty graysa the bottom of the fall, heightening the narrativeof a waterfall in action.Gyokusen’s painting reflects a clear interest in realism.We also see his interest in earlier Japanesepaintings as his work follows a tradition of monumentalwaterfalls by Maruyama Ōkyo. 1 The intenthere was to create the feeling of a real waterfall,which, when hanging in the tokonoma alcove, appearsto come crashing down, the four walls ofthe small room now sheer cliffs and the water rushingdown onto the tatami floor. Just as in the earlierversions by Ōkyo, Gyokusen emphasizes this surrealscene in a small room by the oversized formatof the painting, almost 8 feet in length. 2Gyokusen was born in Kyoto and became the fourthgeneration Mochizuki painter, after taking overfrom his father Gyokusen 望 月 玉 川 (and eventuallyhanding it on to his own son Muchizuki Gyokkei望 月 玉 渓 ). Taught by his father, he took over thefamily workshop and became the appointed courtpainter for the imperial house. He became a leadingfigure of the Meiji-period Kyoto art scene, andtogether with Kōno Bairei 幸 野 梅 嶺 he founded theKyoto Prefectural Art School 京 都 府 画 学 校 in 1878.He was active in foreign exhibitions and won theBronze Medal at the International Paris Expositionin 1889. In his old age, he received numerousnational prizes and honors and retained his closeconnection to the imperial house. 364

15Hirai Baisen 平 井 楳 仙 (1889 –1969)The Snow of Kamogawa River 鴨 川 の 雪Taishō Period (1912 – 26), dated 1917H 50" × W 16 ½" (incl. mounting 85" × 22")(126.7 cm × 41.9 cm, 216 cm × 55.8 cm)Hanging scroll, ink, colors and gofun on silkPainting signature: »Painted by Baisen« 楳 仙 画Painting seal: Baisen 楳 仙Box inscription, top:»The Snow of Kamogawa River« 鴨 川 の 雪Box inscription, inside:»Painted by Baisen on a spring day in 1917.Titled by the artist himself« 丁 巳 春 日 作 楳 仙 自 題Seal: Baisen 楳 仙Box inscription, end:»By the brush of Baisen. Painting of Snow and KamogawaRiver. Matsubara Miyagawa 7-chō. Colorson silk. Matched box«松 原 宮 川 七 丁 楳 仙 筆 鴨 川 雪 の 図 着 色 絹 本共 箱 七 丁It is a winter day with falling snow, the sky darkeningin the late afternoon. We see a footbridge, theMatsubara Bridge, crossing the Kamogawa Riverin Kyoto, to the south of Shijō Street. 1 Outlinedagainst the sky are the Higashiyama mountains onthe eastern side of Kyoto. On the far side of the riverare the teahouses of the Gion entertainment district.The two travelers on the footbridge are headingtoward Gion, perhaps customers preparing tovisit a favorite establishment or perhaps the geishagetting ready for that evening’s performance.The site, the Kamogawa River and the teahousesalong its banks, has long been one of the famoussights of Kyoto. This was the case in the 16th/17thcentury Rakuchū rakugaizu screens and was stillthe case in the time of Hirai Baisen. Further viewsof the area are included in the three albums thatBaisen composed for the tenth Bunten Exhibitionin 1916, depicting thirty different views of Kyoto,entitled Miyako sanjukkei. 2 Interestingly, Baisen alsopainted the Higashiyama mountains of the areaon a pair of monumental landscape screens duringthe late Taishō period, using similar techniques. 3Clearly the artist had no difficulties in adjusting hiscompositions to different scales and formats.The artist was known for his remarkable changes instyle and subject matter. His return from a trip toChina in 1913 inaugurated a period during which hecreated ink landscape paintings of Chinese mountainsand pagodas. 4 Later yet, his attention returnedto Japan and he went into a period of brilliant recreationsof his hometown, Kyoto. Not only did histheme and subject matter change, but so did histechniques and materials used. In place of ink andpaper, he later used silk and heavy Nihonga-stylepigments of mineral colors and gofun, a powderderived from seashells.Baisen was particularly adapt in the use of gofun,which, because of its thick and inflexible consistancy,can be difficult to use and tends to flake off.For this painting, Baisen prepared layers of gofunon the front as well as on the back of the silk. Usingthe white material on both sides of the silk 5 madeit possible to show various shades of white andimpart a sense of depth to the colors. It also makesthe gofun snowflakes stand out more againstthe fine ink wash and gives a feel of looking at alandscape through falling snow. 6Baisen was a leading painter of the twentieth-centuryNihonga movements during Taishō to earlyShōwa periods. 7 An art critic and intellectual, hewas well aware of the history and traditions ofJapanese art, as can be seen in this painting, whichshows references to a line of prior images, fromthe early Rakuchū rakugaizu screens 8 to the 19thcentury landscape prints by Hiroshige to early20th century prints by the Shin hanga artists. Thepainting represents a brilliant reworking of pasttraditions and an evocative new depiction of oneof Kyoto’s famous sights.66

16Watanabe Shōtei 渡 辺 省 亭 (1851–1918)New Year with Small Pines and a Pair of Cranes正 月 小 松 と 雙 鶴Meiji period (1868 –1912), circa 1910H 42 ½" × W 15 ¾" (incl. mounting 75 ½" × 20 ¾")(108 cm × 39.9 cm, 192 cm × 52.6 cm)Hanging scroll, ink, color and lacquer on silkInscription: Shōtei 省 亭Seal: Shōtei 省 亭Box top: »New Year: Small Pines and Crane Pair,Painted by Shōtei.« 正 月 小 松 と 雙 鶴 省 亭 画Box end: »Pair of cranes by the brush of Shōtei,(First) Month.« 雙 鶴 省 亭 筆 [ 正 ] 月Crane paintings have a venerable tradition in Japanand there are numerous well-known works on thetheme. 1 In Japan the co<strong>mb</strong>ination of cranes withyoung pines and the rising sun became a sy<strong>mb</strong>olfor the New Year and displaying such images athomes and institutions became a favorite way towelcome the new season. 2New Year was clearly also the intended messagein this painting, judging from the title that the artistwrote on the tomobako box. Yet, in the hands ofShōtei, one of the greatest animal painters of theMeiji period, the painting becomes much morethan a New Year’s sy<strong>mb</strong>ol. For one thing, Shōteihad a clear interest in portraying animals with realpersonalities. The eye of the upper bird, paintedwith ink and black lacquer, is particularly life-likeand captivating. Through the poses of the birds,we also get a sense of cranes with different personalities:one protecting, the other cowering in theshadow of the larger bird.Further, the co<strong>mb</strong>ination of rough brush strokes atthe tail feathers with fine brush strokes and detailsat the heads and beaks creates interest and vitalityto the scene.Shōtei was one of the most colorful characters inthe art scene of the Meiji period and became a realcelebrity of his time. 3 He was the first Japanesestudent to study in Europe and learned, in 1878 – 81,the Western painting methods of his time. He wonprizes in numerous Western exhibitions—such as inParis in 1878, Amsterdam in 1883, and Chicago in1893—and became one of the best-known Japaneseartists in the West. He also published numerousbooks on paintings, collaborated on cloisonné designs,and courted controversy, for example, bydaring to publish a nude study in the journal Kokuminno tomo in 1889.The level to which he was esteemed by others—andhimself—can be gauged by the striking ichimonjimounting of this hanging scroll: the design is hisown and displays a woven pattern with Shōtei’sown seals, highlighted in silver and gold threads.Shōtei was clearly an artist not afraid to go againstthe conventions nor afraid of standing out in crowd.And as we see in this superb bird study, he hadample reasons to be justifiably proud of his skills.68

18Sano Kōsui 佐 野 光 穂 (1896 –1960)A Cat in a Melon PatchTaishō Period (1912 – 26), circa 1925H 57" × W 20" (incl. mounting 85" × 26")(145cm × 50.7 cm, 216 cm × 65.8 cm)Hanging scroll, ink, colors and gold on silkSignature: Keimei 契 明Seal: Keimei 契 明The technique he uses throughout is tarashikomi,a procedure in which ink, mineral colors and goldare dipped into a still-wet surface of ink. 1 As thetechnique is difficult to control, it is usually done onsized paper; tarashikomi on silk, as in this case, israre. The resulting painting is an elegant display ofthe superlative skills of the artist.A black cat sits among melons and looks out at theworld. The artist presents us here with a strikingcomposition of a cat sitting in unexpected surroundings.The painting is a well thought-out compositionof shapes and colors in which the black furrycat with golden eyes stands out among the lightcoloredspiraling tendrils, decaying flowers, andbulbous melons.Sano Kōsui came from the Nagano prefecture andarrived in Kyoto in 1914 during the Taishō Period,when many great painters were active at the sametime. 2 He was fortunate to become a student undertwo of the leading artists of the time. He first learnedShijō school techniques under Kikuchi Keigetsu菊 池 契 月 (1879 –1955), then Nihonga techniquesunder Tomita Keisen 富 田 渓 仙 (1879 –1936). 3The technical skills of the artist are astonishing:he manages to co<strong>mb</strong>ine the ink, colors and gold—both wet and dry—to create the furry coat of thecat (by making ink seep out into the silk) as wellas the surface patterns of the melon and leaves.The artist was also known for his independence andstrong will. He was ousted from Keigetsu’s studioafter he married against the wishes of his master.Keisen, however, respected his talented student andthe relations between the artist and his new masterremained harmonious.Kōsui moved to Kobe, but returned to Kyoto in 1928,where he stayed for the rest of his professional life.He specialized in paintings of animals and took partin numerous exhibitions. His works were also includedin prestigious national venues, such as theTeiten and the Inten exhibtions. 472

19Tsuji Kakō 都 路 華 杳 (1870 –1931)Daruma PortraitTaishō Period (1912 – 26), circa 1915H 46 ¼" × W 16 ¼" (incl. mounting 84 ¾" × 23")(117.2 cm × 41 cm, 215 cm × 58.2 cm)Hanging scroll, ink and colors on paperSignature, painting: Kakō 華 香Seal, painting: Kakō 華 香Box inscription, top:»Painting of Bodhidharma« 菩 提 達 磨 図Box inscription, signature and seal inside:»Title by Kakō« 華 香 題 and Shishun 子 春This striking portrait of the First Patriarch of Buddhism,Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma) waspainted by the noted Nihonga artist Kakō in theTaishō period. The body and robe of the patriarchare painted with strokes of abstracted repetitions,varying only in density. The heavy layering of coloron Daruma’s chest has resulted in an interestingmottling of the surface, giving a realistic touch.Kakō created a series of Daruma portraits in the1910’s 1 ; as in the other extant examples, there isalso here an emphasis on the chest and the generalhairiness of the Indian patriarch. 2One may well ask why a Nihonga artist would painta series of Daruma images, a topic one wouldrather expect from Zen monks. One reason is Kakō’sstrong belief in Zen Buddhism, which is reflectedin the thirty years of religious training he underwentwith the monk Mokurai (1854 –1930), a Zen Buddhistabbot of the Kenninji Temple in Kyoto. 3 Further,the historical and textual roots of Buddhism werean important theme for the intellectuals of the Taishōperiod. This was the time of the compilation and<strong>publication</strong> of the great Taishō shinshū Daizōkyō, amonumental work of Buddhist scholarship which isstill in use across the world. Therefore an intellectualinterest in Buddhism and in the founder, Daruma,may also have been a reason for the many portraits.Kakō was known for his unusual cutting-edge imagesand succeeds, more than almost any other Japaneseartist of his time, in co<strong>mb</strong>ining Japanese paintingtradition with modernist ideas; here, an old traditionof drawing portraits of Daruma is updated by theartist. 4 For an example of his modernist painting ina screen format, see our 2009 <strong>publication</strong>, item 3.In the past decade, awareness of the artist has growndramatically in the West and Kakō is now well representedin the museums and collections of theWestern world.74

Ba<strong>mb</strong>oo Baskets

21Yamamoto Chikuryūsai 山 本 竹 龍 斎Boat-Shaped Wide Basket 船 形 広 籃Taishō Period (1912 – 26), dated 1916H 15 ¼" × L 20 ¾" × W 11¼"(38.5 cm × 52.5 cm × 28.5 cm)Ikebana flower basketMadake ba<strong>mb</strong>oo, Hōbichiku ba<strong>mb</strong>ooand rattanIncised signature on the bottom:Chikuryūsai kore tsukuru »Chikuryūsai made this«Box inscription, outside:Funagata morikago »Boat-Shaped Wide Basket«Box inscription, inside: early spring, 1916 andsigned Chikuryūsai with a kakihan cipher.This exceptional ikebana basket is a fine exampleof the Chinese karamono-style, in which narrowba<strong>mb</strong>oo strips are plaited symmetrically withgreat precision. Here the strips are plaited in thehexagonal muttsume pattern and supported bywider ba<strong>mb</strong>oo strips held together with rattan.The distinctive four-point handle is attached to thebody with rattan braiding, which covers the entiresurfaces of the handle in an elegant pattern.The basket comes with its original fitted tomobakobox which is lacquered on all surfaces, a sign of thehigh value Chikuryūsai placed on the basket anda treatment generally reserved for karamono-stylebaskets. The box bears the inscriptions, signature,date and cipher of Chikuryūsai.Chikuryūsai must have been very satisfied withthis boat-shaped basket, for when he was offeredthe opportunity to exhibit in Paris in 1925 at theJapanese art exhibition, he made a slightly longerbasket in the same shape and construction. Thisexhibition basket was illustrated in the 1925 catalogand won a silver prize. It is now in the collection ofthe Oita Prefectural Arts and Crafts Museum.80 81

22Maeda Chikubōsai I前 田 竹 房 斎 初 代 (1872 –1950)Wide-Mouthed Flower Basket 広 口 花 篭Shōwa Period (1926 – 89), dated 1942H 19 ½", D 10"(49.5 cm, 25.5 cm)Ikebana flower basketMadaken ba<strong>mb</strong>oo, Hōbichiku ba<strong>mb</strong>ooand rattan.Incised signature on the bottom:Chikubōsai kore tsukuru »Chikubōsai made this«Box inscription, outside:Hiroguchi hanakago »Wide-Mouthed Flower Basket«Box inscription, inside: Autumn day of the 2602ndyear of the Japanese Imperial calender (=1942).Senyō Kuzezato Chikubōsai kore tsukuru»Chikubōsai of the Senyō Studio in Kuzezato madethis« with square red seal mark reading Chikubōsai.This large ikebana basket is made in the Chinesekaramono style, with exacting symmetry andperfection.The bottom is made of ba<strong>mb</strong>oo in the circularamida kōami plaiting, where the ba<strong>mb</strong>oo strips arearranged tangentially to form a circular opening,which is reinforced by two larger ba<strong>mb</strong>oo piecescrossing the center. One of these pieces bears theincised signature reading Chikubōsai made this.The sides are made of narrow strips of split madakeba<strong>mb</strong>oo, plaited in a variation of the ajiro ami twillpattern. The sides are reinforced by six verticalba<strong>mb</strong>oo ribs, which are tightly plaited with rattan.The rim is plaited in no less than five differentpatterns. The handle is made of three Hōbichikuba<strong>mb</strong>oo sections, decorated on the top with fineknotting and held to the body at ten points usingtight rattan knotting.The basket comes with its original fitted kiri-woodtomobako box bearing the inscriptions, signatureand seal mark of Chikubōsai.Chikubōsai was one of the greatest basket makersof the Kansai region. He was active in the goldenage of Japanese basketry, 1910 – 40, when high-qualitybaskets such as this one were eagerly collectedby the Japanese and used in the tea ceremony.Chikubōsai remained active through the secondWorld War and continued to make outstandingbaskets in those difficult years, such as this one in1942 and another, item17 in our 2009 <strong>publication</strong>,in 1941. 1His son, Chikubōsai II (1917 – 2003), continued thebasketry tradition and was named Living NationalTreasure for ba<strong>mb</strong>oo crafts in 1995.82 83

23Tanabe Chikuunsai I田 辺 竹 雲 斎 初 代 (1877 –1937)Crouching Tiger 虎 伏Shōwa Period (1926 – 89), 1920sH 17 ¾", D 10 ¾"(45 cm, 27cm)Ikebana flower basketKinmeichiku ba<strong>mb</strong>oo, Hōbichiku ba<strong>mb</strong>ooand Madake ba<strong>mb</strong>oobottom in the hexagonal muttsume pattern. Thebold handle of Kinmeichiku ba<strong>mb</strong>oo also has anunusually beautiful patina and strength throughits bent form. In fact, the title that Chikuunsai gavethe basket, »Crouching Tiger«, derives from thispowerful handle.Incised signature on the bottom:Chikuunsai kore tsukuru »Chikuunsai made this«Box inscription, outside:Kinmeichiku hanakago torafushi»Kinmeichiku Ba<strong>mb</strong>oo Flower Basket: CrouchingTiger«Box inscription, inside: Sakai-fu nansō Chikuunsaikore tsukuru »Chikuunsai of the Nansō Studio inSakai-fu made this« with two red square seal marksreading Ta[nabe] Tsune[o] no in »seal mark ofTanabe Tsuneo« and Chikuunsai.Chikuunsai was at the apex of his career whenhe made this outstanding basket using smokedHōbichiku ba<strong>mb</strong>oo with rich patina for the basket,plaiting the sides in the hemp-leaf pattern and theThe basket comes with its original lacquered ba<strong>mb</strong>oootoshi tube to hold flowers and water and withits original fitted and inscribed kiri-wood box.For two similar baskets using the same types ofba<strong>mb</strong>oo, see Japanese Ba<strong>mb</strong>oo Baskets: Masterworksof Form & Texture from the Collection ofLloyd Cotsen (Los Angeles: Cotsen OccasionalPress, 1999), item nu<strong>mb</strong>er 85 by Chikuunsai I anditem nu<strong>mb</strong>er 86 by his son Chikuunsai II.Tanabe Chikuunsai, the son of a high-ranking physicianin the Kansai region, studied ba<strong>mb</strong>oo artunder Wada Waichisai I from the age of 18. Afterbecoming independent six years later in 1901,he won numerous awards at national and internationalart exhibitions, including one in Paris in1925. He is especially well known for his precise,detailed karamono-style baskets. He taught numerousapprentices, including Chikubōsai I and hisson, Chikuunsai II. 184 85

24Morita Chikuami森 田 竹 阿 弥 (1877 –1947)Flared Flower Basket 末 広 形 花 籃Shōwa Period (1926 – 89), 1930sH 19", D 10 ¼"(48.5 cm, 26 cm)Ikebana flower basketHōbichiku smoked ba<strong>mb</strong>oo and rattanIncised signature on the bottom:Chikuami kore tsukuru »Chikuami made this«Box inscription, outside:Suehiro gata hanakago »Flared Flower Basket«Box inscription, inside:Chikuami zō »Made by Chikuami«with a round red seal mark reading Chikuami.Collector’s label on the box reads Takekagohanaike or »Ba<strong>mb</strong>oo Basket Flower Vessel«a warm patina over time. To add to an aged, rusticlook, sabi or charcoal powder was dusted onto thesurfaces and then only partially brushed away, remainingin corners and cracks. The body is plaitedin an irregular ajiro ami or twill pattern and alongthe vertical ba<strong>mb</strong>oo strips and the handle are fancyknots made with rattan.The basket is square on the bottom, flaring out toa larger round opening. This suehiro or flaring shapeis auspicious in Japan, as it sy<strong>mb</strong>olizes growth andimprovement, starting small and growing in size.On the bottom edge is the artist’s finely incisedsignature. The basket is complete with the originalotoshi ba<strong>mb</strong>oo tube to hold the flowers and waterand the original fitted tomobako box.This basket in the Japanese taste was made to lookrustic, using old hōbichiku smoked ba<strong>mb</strong>oo andincluding knobbed node sections in the design.After plaiting, the outer surfaces were lacqueredwith a red-brown natural lacquer that has acquiredChikuami is the artist name of Morita Shintarō, whowas active in Kyoto in the early Shōwa period. Forthis basket in the Japanese style (as opposed to thekaramono Chinese style) he used Hōbichiku ba<strong>mb</strong>oo,which is a smoked ba<strong>mb</strong>oo traditionally used in farmhouse ceilings. They can be hundreds of years oldand have gained a warm rich-colored patina fromage and from hearth smoke.For another basket by Chikuami in the karamonoChinese style, see our 2006 <strong>publication</strong>, item 13.86 87

25Kyokusai 旭 斎 (ac. 1910 – 40)Flower Basket 花 籠Shōwa Period (1926 – 89), dated 1937H 17" × L 9 ¼" × W 7"(43.3 cm × 23.5 cm × 18 cm)Ikebana flower basketSusudake ba<strong>mb</strong>oo and rattanIncised signature on the bottom:Kyokusai saku »Made by Kyokusai«Box inscription, inside: Hanakago »Flower Basket«and Kyokusai saku »Made by Kyokusai« with a rectangularred seal mark reading Kyokusai. DatedApril, 12th year of Shōwa (=1937).For a basket of similar shape and constructionusing light-colored ba<strong>mb</strong>oo, see Japanese Ba<strong>mb</strong>ooBaskets: Masterworks of Form & Texture from theCollection of Lloyd Cotsen (Los Angeles: CotsenOccasional Press, 1999), item nu<strong>mb</strong>er 210, entitledMagaki or »Fence.«Kyokusai is believed to have studied under SuzukiKyokushōsai 鈴 木 旭 松 斎 and to have worked inTokyo from the Taishō to early Shōwa periods.This elegant masterpiece follows the Sensuji gumior thousand-line construction, with parallel rows ofnarrow susudake ba<strong>mb</strong>oo strips held together bylines of rattan plaiting. Looking closely, one noticesthat Kyokusai cleverly arranged the ba<strong>mb</strong>oo stripsso that the nodes appear on the bottom only. Thisarrangement keeps the sides smooth withoutdistracting irregularities and reinforces the pure,minimalist design.88 89

Lacquers

26Incense Box with the Full Moonand NantenEdo Period (1615 –1868), 18th CH 1" × L 2 ¾" × W 2 ¾"(2.3 cm × 6.8 cm × 6.7 cm)Lacquer boxin gold, silver, red and green hiramakie lacquer.The insides and the bottom are sprinkled withsmall nashiji gold flakes and the rims are createdof pewter.Box inscriptions:Kaneda 金 田Hōjuten 宝 珠 店»Nu<strong>mb</strong>er nine« 九 番In this evocative autumn view, we see sprays of theNanten 南 天 (Nadina, Nandina domestica) againstthe full moon. The season is indicated by the Nanten’slingering blossoms on its branch tips and byits reddening berries that fully ripen in late autumn.With its red fruits, the Nanten became a sy<strong>mb</strong>olof winter, and the red berries are often depictedby Japanese artists who contrast them againstthe white snow. Here, however, the Nanten is usedas a marker of the late autumn. The full moon onthe box is also associated with autumn in Japan, asit is thought to be most beautiful in that season.The scene depicts the melancholy moments of lingeringbeauty, just before the winter sets in. 1The kōgō comes with an old fitted kiri-wood boxinscribed on the inside of the cover and on thebottom with collector’s nu<strong>mb</strong>ers and marks and thename of an art shop, the »Shop of the TreasuredJewels« the Hōjuten 宝 珠 店 .The Kōgo incense box is formed in a roundedsquare shape and decorated on the top with thefull moon in gold and silver togidashi lacquer.Around the moon and on the sides of the kōgo arebranches, flowers and berries of the Nanten plant92 93

27Writing Box with Fans andAutumn GrassesMeiji Period (1868 –1912), circa 1900H 1½" × L 8" × W 7 ¼"(4 cm × 20.4 cm × 18.4 cm)Maki-e lacquer boxInscription (on box top): »Autumn grasses patternlacquer writing box« 秋 草 模 様 蒔 絵 硯 筥Inscription (on end of box): »Small type writing box,autumn grasses pattern, received from Mr. Nagata.«小 形 硯 箱 秋 草 蒔 絵 永 田 氏 ヨリThe two gold-lacquer fans on the cover of this superbrectangular suzuribako writing box distinctlystand out against the roiro mirror-black ground.The upper fan is decorated with a scene of chrysanthemumflowers by a ba<strong>mb</strong>oo fence and floweringtrees, rocks, waterfall and stream; the lowerfan with a palace building by a garden with pines,cherry blossoms and fence, all surrounded by goldenclouds. The décor is executed in finely-detailedhigh-relief takamakie gold, silver and red lacquerwith additional details in hiramakie and togidashilacquer and many inlays of irregularly-cut kiriganegold foil squares and triangles. The curved outsideedges of the box are lacquered in togidashi goldlacquer; the rims of the box and of the ink stone insideare in solid silver.The writing box contains numerous references tothe literary traditions of courtly Japan, specificallyto those of the Heian period, which was seen bymany as the pinnacle of Japanese cultural achievements.The décor on the cover refers to a Heiancourt tradition, the exchange of fans decoratedwith painting or calligraphy. 1 The building on thelower fan is in the Heian period shinden-zukuripalatial architecture style, with references to Heianperiod Tales of Genji paintings, which featuredsimilar settings with finely tended gardens. Ascan be seen in item 2 of the present <strong>publication</strong>,scenes from Genji were also painted on foldingscreens in the Momoyama and Edo periods andsuch compositions would have been familiar tome<strong>mb</strong>ers of the educated elite.The veranda of the palace building on the fan,however, is without its Prince Genji. The stage waslikely left open by the artist to impart a genericHeian flavor to the composition without anchoringit to a specific text or scene. Perhaps it was leftopen so that the owner of the writing box could imaginehimself in the role of the Heian-period aristocrat,about to open the box to brush a poem toa distant lover.Opening the writing box, one is rewarded witha dramatic view of a multitude of swaying fallgrasses, the Japanese pampas grass susuki 薄 , inhiramakie gold and silver lacquer with the roundsuzuri ink stone representing the full moon. Thisinner composition refers to the Autumn MoonFestival, the Jūgoya 十 五 夜 , which is often sy<strong>mb</strong>olizedby susuki and the full moon. The festival takesplace on the 15th day of the 8th month of thelunar calendar (usually mid- to late-Septe<strong>mb</strong>er inthe Gregorian calendar), a date that parallels theautumn equinox in the northern hemisphere. Thetraditional food for this festival is the round caketsukimi dango 月 見 団 子 , which echoes the shapeand color of the distant moon.The writing box comes complete with the originaltwo brushes, paper cutter and suiteki water dropperin the shape of shikishi poetry cards, all lacqueredin togidashi gold lacquer; and with the original kiriwoodfitted box.94 95

28Writing Box with BooksEdo Period (1615 –1868), early 19th CH 2" × L 9" × W 8 ¼"(4.9cm × 22.8 cm × 21 cm)Maki-e lacquer boxInscriptions (on end of outer box): 1) »Gold lacquerwriting box with books« 本 蒔 絵 硯 箱 ; 2) »Nu<strong>mb</strong>erseven. Strewn gold flakes and gold lacquer ofbooks. Writing box, one piece«七 番 なし 志 本 のまきへ すすり 箱 一 ツThis exquisitely crafted gold-lacquer suzuribakowriting box, rectangular with rounded corners, isdecorated on the cover with two Japanese books,placed partly on top of each other, in raised takamakiegold lacquer. The top book is decoratedwith a dragon in dark clouds, with a multitude ofkirigane gold-foil inlays; the lower book depictsphoenix roundels and seasonal flower bouquetsin minutely-detailed gold takamakie lacquer on adiamond-shaped floral pattern in gold and silvertogidashi lacquer. The books each have a title paperin respectively gold and silver foil.a rectangular silver suiteki water dropper and isdecorated with more waves in gold and silvertogidashi. Below the tray, on the inside bottom ofthe writing box, are fifteen Chidori plover birds inhiramakie gold lacquer, flying in a circular pattern.The scene refers to a poem from the famous poetryanthology, the Kokin wakashū:The plovers dwelling in Sashide Bay by its the saltycliffs cry yachiyo, wishing our lord a reign of eightthousand years.しほの 山 さしでの 磯 にすむ 千 鳥 君 がみ 代 をばやちよとぞ 鳴 く 1The elements of plovers, cliffs and the oceanco<strong>mb</strong>ine to make a poetic allusion to the wish fora long rule. The plovers’ cry chiyo, homophonouswith chiyo 千 代 »a thousand years« is a call for longrule. This is changed here by the poet to yachiyo八 千 代 »eight thousand years« and, by extension,eternal rule and a reference to Japan’s Imperial line.The dramatic design on the inside cover featuresa large red sun appearing behind narrow clouds,rising above craggy rocks in a stormy sea. The sunis decorated in red and gold togidashi lacquer,and the clouds and rocks in raised takamakie goldlacquer with a tour-de-force inlay of kirigane goldfoil pieces cut in irregular squares and triangles.The ocean waves are depicted in gold and silvertogidashi lacquer with further details of abaloneand aquatic plants in hiramakie gold lacquer. Theremovable tray holds the suzuri ink stone andSy<strong>mb</strong>olically the strong cliffs in the design are rulerssteadfast in the stormy sea and the birds are subjectsflying in circles around the cliffs, all under theimposing large red rising sun, the sy<strong>mb</strong>ol of theJapanese state. The two book covers of the writingbox, depicting volumes from a poem anthology,introduce other allusions and sy<strong>mb</strong>ols: the dragonrising out of the sky as a sy<strong>mb</strong>ol of the male elementand the roundels of phoenix and chrysanthemumas female elements.The edges of the writing box cover are decoratedwith minute karakusa scrolling and diamond patternsin hiramakie gold lacquer. The writing boxcomes with its original double fitted storage boxes,both in black lacquer, the outer one bearing twoinscribed collector’s labels. On the inside of thestorage box is pasted poetry paper with a dyed designsimulating poetry sheets used in Heian-periodcalligraphic works.96 97