Animal Cards - Project Wild

Animal Cards - Project Wild

Animal Cards - Project Wild

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................G r a s s h o p p e r G r a v i t yGrasshopper QuestionsInteresting FeaturesWhat are the features of a grasshopper?LegsHow many legs does it have? Are they alikeor different? Which legs are the jumping legs?Notice where the legs are attached to thegrasshopper’s body.WingsLook at the wings, if they are present. How manywings are there? Notice where they attach tothe body.HeadLook at the head. How many eyes do you see? Dothey look like your eyes? Check carefully in frontand below the large, compound eyes for threesmaller, simpler eyes. Why do you think they haveso many eyes? These eyes probably see light butmay not be able to see shapes, sizes, and colors.MouthDo you see a mouth? Does the grasshopper havelips? Try to feed the grasshopper a leaf to watchthe mouth parts move. Hold the leaf up to themouth just touching it. Do not try to put the leafin the mouth, of the grasshopper. Try to describethe mouth parts and how they move.AntennaeWhere are the antennae? Are they each a long,string-like, single appendage, or are they made upof many parts? Can you count the parts? Do theyall look alike in size, shape, and color? Why doyou think a grasshopper needs the antennae? Forwhat? Think about radio and television antennae.MotionWe usually think that grasshoppers “hop.” Dothey also walk? How do they walk on the groundor floor? If possible, watch the grasshopper climba small stick, weed stem, or blade of grass. Doesit use all of its legs? Without hurting yourgrasshopper, place it on the ground and makeit jump (if it is an adult with wings, it may flyinstead). Follow it and make it hop or jumpseveral times (at least five times). Does it hopthe same distance each time? Measure or estimatethe distance of each hop or flight. Does thegrasshopper seem to get tired? What makesyou think so?NoiseDo grasshoppers make noises? If your grasshoppermakes a noise, try to learn if it does it with itsmouth or with some other part of its body.ColorsLook at the whole grasshopper carefully. Is itthe same color all over? Are the colors, shapes,and sizes the same on both sides? What is attractiveabout your grasshopper? Is it clean? Watchto see what the grasshopper does to clean orgroom itself.HabitatWhere does the grasshopper live? What does iteat? Do grasshoppers live in your neighborhoodyear-round? Suggest two reasons why grasshoppersmight not be seen during the winter (such asfreezing temperature, not enough food).ConclusionsDid you think there were so many interestingthings about grasshoppers? Do you think otherinsects might be as interesting? What other insectsor small animals might be interesting to look atand learn more about?....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 3

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................H a b i t a t R u m m yHabitat Information Chart<strong>Animal</strong>sLizard Osprey Bear ChipmunkFoodInsectsFishInsects, Fish,Berries, Birds,Eggs,MammalsSeeds,BerriesHabitat ComponentsWaterShelterSpaceFreshwater(as available)Rock CrevicesHillsidesWater(as available)Cliffs,Sand DunesOcean CoastsRivers, Lakes,StreamsCavesHills, ValleysFreshwater(streams,ponds, dew)BurrowsHillsidesArrangementDesertsCoastsand InlandWoodlandMeadowWoodlot4....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................H a b i t a t R u m m yShelter Space Food Water ArrangementBurrowHillsidesSeeds, BerriesStreams,Ponds, DewWoodlands,MeadowsShelterSpaceFood WaterArrangementCavesHills, ValleysInsects, Birds,Eggs, Seeds, Nuts,Berries, Fish, MammalsLakes, Streams,SnowWoodland....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 5

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................H a b i t a t R u m m yShelter Space Food Water ArrangementRock CrevicesHillsidesInsectsAs AvailableDesertOSPREY OSPREY OSPREY OSPREY OSPREYShelter Space Food WaterArrangementCliffs,Sand Dunes Ocean CoastFishAs AvailableAquatic6....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................B e a r l y G r o w i n gWEIGHT AND AGE RELATIONSHIPSFOR BLACK BEARS CHART(Data are characteristic of black bears in the southwestern United States.There will be regional variations.)....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 7

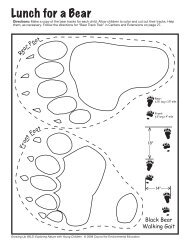

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................B e a r l y G r o w i n gPart I: For use in completing chart on page 22Black Bear BiologyThe black bear (Ursus americanus) can be foundin the United States, Canada, and Alaska. In theeast, the black bear primarily inhabits forestsand swamps. In the west, the black bear roamschiefly in mountainous areas. Black bears areprimarily nocturnal but occasionally roamaround during the mid-day.A black bear’s life span averages 20 to 25 years.Longevity and survival of the black bear dependupon the availability of a suitable habitat and itsability to avoid humans. An adult female bearis called a sow. An adult male bear is called aboar. A baby bear is called a cub. When a sowbecomes sexually mature between 2 and 3 yearsold, she is capable of breeding and may have oneto four cubs. Contrasted with human fetal developmentof about 9 months, the sow is pregnantfor about 7 months.The sow has her cub or cubs in the shelteror den where she spends the winter months.On average, a female black bear will have twocubs. The sow does not have a litter every yearbut every other year. At birth, a young cubweighs about 8 ounces—about the size of aguinea pig. Bear cubs stay in the den with theirmother until they are able to move around veryactively, usually until late April or early May.Bears and humans are classified as mammals,which means that both are warm-blooded, nourishtheir young with milk, and are covered withvarying amounts of hair. Bear cubs and humanssurvive solely on their mother’s milk for the firstfew months of life. Cubs nurse while inStudent Data Pagethe den and only for a short time after leavingthe den in early spring. By the time berries ripenand grasses are plentiful, the cubs have learnedto climb and can eat the available food sources.Soon the cubs will need to hunt and gather foodfor themselves without the help of the sow. Atabout 18 months of age, the cubs must go outsearching for their own home range. The sowwill allow the female cubs to stay within herhome range. The male cubs, however, must findterritory to claim as their own.Black bears are omnivores, which means they eatboth plant and animal material. In early spring,they tend to eat wetland plants, grasses, insects,and occasionally carrion (dead animal matter) orthe protein-rich maggots found near the carrion.In late spring and early summer, bears feed onberries, grubs, and forbs (broad leafed plants). Inlate summer and early fall, bears feed mostly onnuts and acorns. In the fall season, bears mustadd much fat to their bodies in order to survivethe winter months in their dens. Cub growthwill vary throughout the country.When black bear cubs reach one year of age, thefemale cubs weigh 30 to 50 pounds and themales weigh 50 to 70 pounds. A mature femalebear weighs 150 to 185 pounds, and a male bearweighs about 275 pounds. (Sources: ArkansasBlack Bear: A Teacher’s Guide for KindergartenThrough Sixth Grade, Arkansas Game and FishCommission; WILD About Bear, ID Dept of Fishand Game and; A Field Guide to the Mammals,Houghton Mifflin Co., 1980).Table APart II: For use in completing the evaluation on page 20Catfish in Lake Erie and the Ohio RiverAGE IN YEARS1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9Lake Erie catfish 69 115 160 205 244 278 305 336 366Ohio River catfish 56 101 161 227 285 340 386 433 482(size in mm)8....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................B e a r l y G r o w i n gCompare Yourself to a Black BearThe average height of an adult male blackbear standing upright:Your height:The weight of an adult male black bear:Your weight:The average weight of a 1-year-old maleblack bear:Your weight at 1 year of age:The average birth weight of a black bear cub:Your birth weight:The average number of cubs that a black bearhas per litter:Average number of babies your mom had atone time:The length of time a cub stays with its mother:Number of years you probably will stay athome:The range of a black bear’s life span:Average person’s life span:....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 9

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................T r a c k s !Clean trackand spray withshellac orclear plasticCircle the track with acardboard damFill the damwith plasterOnce hardened, remove the damand clean the plasterDon’t forget apetroleum jelly coatingstapleCoat the cast withpetroleum jellyTwicethe sizeof thefirstMake a larger damand fill with plasterOnce the plaster hardens,remove the dam andseparate the partsPaint the finished trackso it looks realistic10 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................T r a c k s !Source: J. J. ShomonReprinted from Virginia <strong>Wild</strong>life Magazine....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 11

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................O h D e e r !12 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................H a b i t r a c k s....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 13

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................R a i n f a l l a n d t h e F o r e s t..14 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eH a b i t r e k k i n gGROUP #1HABITREKKING EVIDENCE LIST #1Caution: You may bring back evidence, but becareful not to harm the wildlife or environment.Find Evidence That1. Humans, domesticated animals, and wildlifeall need food, water, shelter, and space arrangedso they can survive.2. All living things are affected by theirenvironment.3. <strong>Animal</strong>s—including people—depend onplants—either directly or indirectly.GROUP #2HABITREKKING EVIDENCE LIST #2Caution: You may bring back evidence, but becareful not to harm the wildlife or environment.Find Evidence That1. Humans and wildlife share environments.2. <strong>Wild</strong>life is everywhere.3. <strong>Wild</strong>life can be in many forms and colors, andcan have special features that help it live inits environment.GROUP #3HABITREKKING EVIDENCE LIST #3Caution: You may bring back evidence, but becareful not to harm the wildlife or environment.Find Evidence That1. Humans and wildlife are subject to the sameor similar environmental problems.2. The health and well-being of both peopleand wildlife depend on a good environment.3. Environmental pollution affects people,domesticated animals, and wildlife.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 15

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eM i c r o t r e k T r e a s u r e H u n tWILDLIFE TREASURE HUNTThis is a treasure hunt to look for evidenceof wildlife.CAUTION: Be careful not to harm any animalsor their homes.Find evidence that1. Humans and wildlife share the sameenvironment.2. Humans and wildlife must adjust to theirenvironment, move to a more suitableenvironment, or perish.3. <strong>Wild</strong>life is all around even if it’s not seenor heard.4. <strong>Wild</strong>life can be many different sizes.5. People and wildlife experience some of thesame problems.6. Both people and wildlife need places to live.WILDLIFE TREASURE HUNTThis is a treasure hunt to look for evidenceof wildlife.CAUTION: Be careful not to harm any animalsor their homes.Find evidence that1. Humans and wildlife share the sameenvironment.2. Humans and wildlife must adjust to theirenvironment, move to a more suitableenvironment, or perish.3. <strong>Wild</strong>life is all around even if it’s not seenor heard.4. <strong>Wild</strong>life can be many different sizes.5. People and wildlife experience some of thesame problems.6. Both people and wildlife need places to live.WILDLIFE TREASURE HUNTThis is a treasure hunt to look for evidenceof wildlife.CAUTION: Be careful not to harm any animalsor their homes.Find evidence that1. Humans and wildlife share the sameenvironment.2. Humans and wildlife must adjust to theirenvironment, move to a more suitableenvironment, or perish.3. <strong>Wild</strong>life is all around even if it’s not seenor heard.4. <strong>Wild</strong>life can be many different sizes.5. People and wildlife experience some of thesame problems.6. Both people and wildlife need places to live.WILDLIFE TREASURE HUNTThis is a treasure hunt to look for evidenceof wildlife.CAUTION: Be careful not to harm any animalsor their homes.Find evidence that1. Humans and wildlife share the sameenvironment.2. Humans and wildlife must adjust to theirenvironment, move to a more suitableenvironment, or perish.3. <strong>Wild</strong>life is all around even if it’s not seenor heard.4. <strong>Wild</strong>life can be many different sizes.5. People and wildlife experience some of thesame problems.6. Both people and wildlife need places to live.16 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eG o o d B u d d i e s<strong>Animal</strong>s Relationship CommentsBarnacle/Whale Commensalism Barnacles create home sites by attaching themselves to whales.This relationship neither harms nor benefits the whales.Remora/Shark Commensalism Remoras attach themselves to a shark’s body. They then travelwith the shark and feed on the leftover food scraps from theshark’s meals. This relationship neither harms nor benefitsthe shark.Bee/Maribou stork Commensalism The stork uses its saw-like bill to cut up the dead animals it eats.As a result, the dead animal carcass is accessible to some beesfor food and egg laying. This relationship neither harms norbenefits the stork.Silverfish/Army ants Commensalism Silverfish live and hunt with army ants, and share the prey.They neither help nor harm the ants.Hermit crab/Snail shell Commensalism Hermit crabs live in shells made and then abandoned by snails.This relationship neither harms nor benefits the snails.Cowbird/Bison Commensalism As bison walk through grass, insects become active and are seenand eaten by cowbirds. This relationship neither harms norbenefits the bison.Yucca plant/Yucca moth Mutualism Yucca flowers are pollinated by yucca moths. The moths lay theireggs in the flowers where the larvae hatch and eat some of thedeveloping seeds. Both species benefit.Honey guide bird/Badger Mutualism Honey guide birds alert and direct badgers to bee hives. Thebadgers then expose the hives and feed on the honey first.Next the honey guide birds eat. Both species benefit.Ostrich/Gazelle Mutualism Ostriches and gazelles feed next to each other. They both watchfor predators and alert each other to danger. Because the visualabilities of the two species are different, they each can identifythreats that the other animal would not see as readily. Bothspecies benefit.Oxpecker/Rhinoceros Mutualism Oxpeckers feed on the ticks found on a rhinoceros. Bothspecies benefit.Wrasse fish/Black sea bass Mutualism Wrasse fish feed on the parasites found on the black sea bass’sbody. Both species benefit.Mistletoe/Spruce tree Parasitism Mistletoe extracts water and nutrients from the spruce tree tothe tree’s detriment.Cuckoo/Warbler Parasitism A cuckoo may lay its eggs in a warbler’s nest. The cuckoo’syoung will displace the warbler’s young, and the warbler willraise the cuckoo’s young.Mouse/Flea Parasitism A flea feeds on a mouse’s blood to the mouse’s detriment.Deer/Tick Parasitism Ticks feed on deer blood to the deer’s detriment.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 17

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eG o o d B u d d i e sMaster <strong>Cards</strong>18 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eG o o d B u d d i e sMaster <strong>Cards</strong>ARMYANTS....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 19

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eW h a t ’ s f o r D i n n e r ?20 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eE n e r g y P i p e l i n eOne possible arrangement for the energy system in a classroom:Bucket of GravelBacteria Team (optional)Sun TeamBucket for Used-Up CaloriesPlantTeamsHerbivoreTeamsCarnivoreTeamDiagram A....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 21

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eE n e r g y P i p e l i n eCarnivoreRound 1Total Growth ChartRound 2 Round 3(optional)(optional)Growth Calories Growth Calories Growth Calories NutrientsHerbivorePlantBacteria22 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eE n e r g y P i p e l i n ePlant Metabolism <strong>Cards</strong>Unused SunlightNot all sunlight can beconverted into organic matter.Place two calories in this bowl.ReproductionPlant uses energy toproduce seeds.Place three calories in this bowl.GrowthPlant uses energy to grow.Place one calorie in this bowl.PhotosynthesisPlant absorbs energy fromthe sun and producesorganic matter.Place three calories in this bowl.RespirationPlants burn energy in theprocess of photosysthesis.Place one calorie in this bowl.Herbivore Metabolism <strong>Cards</strong>DigestionHerbivore uses energy to breakdown consumed food.Place two calories in this bowl.MovementHerbivore uses energy tosearch for water.Place three calories in this bowl.ReproductionHerbivore uses energy to createnest and raise young.Place three calories in this bowl.GrowthHerbivore uses energy to grow.Place one calorie in this bowl.RespirationHerbivore uses energy towatch for predators.Place one calorie in this bowl.Carnivore Metabolism <strong>Cards</strong>DigestionCarnivore uses energy to breakdown consumed food.Place two calories in this bowl.MovementCarnivore uses energy to searchfor prey and to hunt food.Place three calories in this bowl.RespirationCarnivore uses energy to builda shelter.Place one calorie in this bowl.ReproductionCarnivore uses energy forextensive courtship display andextra hunting to raise young.Place three calories in this bowl.GrowthCarnivore uses energy to grow.Place one calorie in this bowl.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 23

........................................................................................................E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g eB i r d s o f P r e y24 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................W h a t B e a r G o e s W h e r e ?© Pat Oldham 1993....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 25

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................P o l a r B e a r s i n P h o e n i x ?26 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................A d a p t a t i o n A r t i s t r yAdaptation Bird AdvantageBeaks• Pouch-like Pelican Can hold the fish it eats• Long, thin Avocet Can probe shallow water and mud forthe insects it eats• Pointed Woodpecker Can break and probe bark of trees for theinsects it eats• Curved Hawk Can tear solid tissue for the meat it eats• Short, stout Finch Can crack the seeds and nuts it eats• Slender, long Hummingbird Can probe the flowers for nectar it eatsFeet• Webbed Duck Aids in walking on mud• Long toes Crane, Heron Aids in walking on mud• Clawed Hawk, Eagle Can grasp food when hunting prey• Grasping Chicken Aids in sitting on branches, roosting, protectionLegs• Flexor tendons Chicken Aids in perching, grasping• Long, powerful Ostrich Aids running• Long, slender Heron, Crane Aids wading• Powerful muscles Eagle, Hawk Aids lifting, carrying preyWings• Large Eagle Aids flying with prey, soaring while huntingColoration• Bright plumage Male birds Attraction in courtship, mating rituals• Dull plumage Female birds Aids in camouflage while nesting• Change of Owl, Ptarmigan Provides camouflage protection (brownplumage within summer, white in winter)seasons....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 27

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................M u s k o x M a n e u v e r s28 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................I ’ m T h i r s t yI’m Thirsty<strong>Animal</strong>s can have incredible adaptations in order tosurvive in their environments. Use the following hypotheticalexample of the desert bighorn sheep: Thedesert bighorn live in dry, sparsely vegetated areas ofthe southwestern United States. Temperatures on summerdays are frequently over 100° F (37.8° C). Duringthe hottest months of summer, ewes (females) andlambs come to waterholes almost daily. The male sheep(rams) sometimes do not come to water for nearly aweek at a time. Rams may roam 20 miles (32 kilometers)away from the available water supply. Add 20miles (32 kilometers) to the approximately 5 miles(8 kilometers) traveled per day, and rams may travelalmost 75 miles (120 kilometers) before they drinkagain. Rams are believed to drink approximately 4 gallons(15.2 liters) of water when they do come to water,while an ewe drinks approximately 1 gallon (3.8 liters)and a lamb drinks 2 pints (940 milliliters).Questions for Students1. How many miles to the gallon (or kilometersper liter) does a ram get?2. How many gallons (or liters) of water would a ramdrink in a month?3. How many gallons (or liters) of water would a ewedrink in a month?4. How many gallons (or liters) of water would a lambdrink in a month?5. How much water must be available in a waterholefor 10 rams, 16 ewes, and 7 lambs in order for themto survive the months of June, July, and August?6. What rate of inflow would a waterfall have tohave to sustain the population given above ifwater evaporated at a rate of 10 gallons (38 liters)per day?....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 29

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................F i r e E c o l o g i e sTable AField Investigation DataRecent Fire Area Fire 10–15 Years Ago No Recorded FireSoil DataPlant SpeciesAssociated <strong>Wild</strong>life/Evidence of <strong>Wild</strong>life<strong>Wild</strong>life ObservedTable BConsequences to SpeciesShort-Term Long-Term Short-Term Long-TermBenefit Benefit Harm HarmPlants<strong>Animal</strong>s30 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................M o v e O v e r R o v e r<strong>Animal</strong> <strong>Cards</strong>1.This bird likes to flyclose to the groundand lives in openor semi-open areas.It builds nests of mudand grass.2.This mammal lives indeserts, forests, andgrasslands near rockyoutcrops. It feeds oncrickets, grasshoppers,scorpions, and spiders.3.This mammal feedson the inner layer oftree bark with the helpof its large front teeth. Itblocks streams andrivers with its dam.4.This mammal mustbe sure-footed to reachthe sparse grass uponwhich it feeds.This mammal hunts atnight and makes itsden in rock crevicesand hollow logs.This amphibian isan incredibly smallwood toad.5.6.This bird huntsat night. It lives inunderground burrowsof animals.This insect’s larvae feedon crops of alfalfa.7.8.9.This animal feeds onseeds and acorns nearstreams and is commonaround camp sites.10.This mammal eats smallrodents, rabbits, andbirds. It also eats theremains of animalskilled by wolves andmountain lions.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 31

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................M o v e O v e r R o v e r<strong>Animal</strong> <strong>Cards</strong>This mammal nests inthe ground, in trees, andin stumps. It eats seeds,nuts, and acorns, andit stores its food.This tick feeds on theblood of mammals.11.12.This insect laysits eggs in water.The mature insect canbe seen flying andusing its large wings.This mammal’s hauntingmating calls echothrough thehigh-country inlate fall.13.14.15.This bird hunts largerodents, such as rabbits,during the day. It usesits keen eyesight tolocate prey as itsoars in the sky.16.This insect eatslarge amounts ofvegetation. It lives inplaces that producelots of green plants.This bird uses its longlegs to walk through stillwater and to hunt fishand water snakes.This bird hunts at nightfor rodents and snakes.It gets its name from thetwo tufts of feathers onthe top of its head.17.18.This mammal uses itsstrong hind legs toescape predators.This mammal getsthe water it needsfrom the plants it eats.19.20.32 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................M o v e O v e r R o v e r<strong>Animal</strong> <strong>Cards</strong>21.This mammalcan live in many kindsof places near water.It often nests in theburrows of otheranimals or underwood or rock piles.22.This mammal isa good swimmer.It often feeds ongrasses, seeds, andbark.23.This mammal is anexcellent swimmer.It eats eggs, frogs,crayfish, birds,and fish.24.This large mammaleats twigs and barkin winter and waterplants in summer inareas where beaversare common.This insect feedson the bloodof many animals.It lays its eggs instill water.This mammal eats brushand sparse grasses.Its name comes fromits large ears.25.26.This mammal eats mostlyaquatic plants but itmay also eatfrogs, clams, and otheraquatic animals.27. 28.Once nearly extinct,this fast predatorybird has made aremarkable recoverysince the ban of thepesticide DDT.This mammal eatsthe bark of pine trees.It protects itself with itssharp, pointed quills.This mammal’s burrowprovides homes forother animals, includingburrowing owls.29.30.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 33

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................M o v e O v e r R o v e r<strong>Animal</strong> <strong>Cards</strong>This mammal runsincredibly fast in thewide-open spacesit lives in.31. 32.This mammal eatsmany foods and maydunk the food in waterbefore eating. It oftenlives in hollow logs.This brightly colored fish has been stockedin many areas and has moved into the territories33.of many native species.34.This reptile warns intrudersto stay away with itsrattling sound.35.This mammal uses itshunting skills to catchdeer mice and othersmall mammals.36.This bird roosts inflocks near open wateror in open areas.37.This fish-eating mammallives alongstreams, lakes, marshes,and rivers.38.This insect does not develop large wingsbecause of high winds.This mammal comesout at night, and itsleeps in groundburrows, wood, orrock piles.This mammal changescolor with the seasons,which allows it toescape predators.39.40.34 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................M o v e O v e r R o v e r<strong>Animal</strong> <strong>Cards</strong>This popularcatch for anglersis very colorful.This spider looksdangerous, but ithunts only insects.41.42.This amphibian lives in or near water its entire life.It lives in mud at the bottom of the water43.during winter.44.This bird survives theextremely cold winters byroosting in snow drifts andby eating energy-rich willowbuds. Its plumage issnow-white in the winterand mottled brown inthe summer.This bird eats insectsthat live under the barkof trees.Larvae ofthis insect feed onyucca flowers.45.46.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 35

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................H e r e T o d a y , G o n e T o m o r r o wState or ProvinceNational<strong>Animal</strong> NameExtinctEndangeredCriticallyEndangeredThreatenedRarePeripheralExtinctEndangeredCriticallyEndangeredThreatenedRarePeripheralFactors Affecting<strong>Animal</strong>’s Status36 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................T i m e L a p s eForest Diagram....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 37

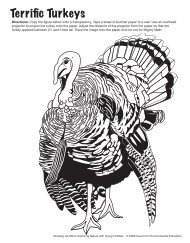

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................T i m e L a p s eSample <strong>Animal</strong>sCardinalGrasshopperGarter SnakeToadOwlRobinBear Sparrow SongbirdMouse Squirrel FoxRabbit Deer TurkeyQuail38 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................T i m e L a p s eDescriptions of Three Successional StagesNOTE: An area of the forest has been clean harvested and abandoned. A fire occurred on the site afterit was abandoned.3 to 5 YearsThe first plants to invade prefer bright sunlight. The fire released many of the nutrients in stumpsand branches left behind during the cutting of the area. Grasses—such as broom straw, golden rod,and other herbaceous plants—have taken over the area. The area is also green with sprouts from treestumps that were not killed by the fire. Woody shrubs—such as blackberry, wild grape, sumac, andviburnums—are beginning to grow. Here and there, a young coniferous tree—such as red cedar orfield pine—is beginning to reach above the grasses.15 to 25 YearsThe overall vegetation is dense as the plant community converts from shrubby field to forest. Maples,birches, oaks, and other hardwoods join pines and cedars. Few acorns and other nuts are being produced.Vertical layers are becoming distinct. At 25 years, the young hardwoods are approximately40 feet tall and starting to shade out “sun-loving” shrubs such as blackberries and brambles. Othershrubs more tolerant of shade—such as blueberry, serviceberry, and spice bush—may continue to grow,although the blueberry will not produce as many berries. Hemlock and white pine, which thrive inunder-story shade, may begin to grow.More Than 100 YearsAs taller plants occupy the site, less light is available on the surface of the forest. Plants tolerant ofshading will out-compete plants that are intolerant of shading, and gradually the composition of theforest will change to favor shade-tolerant species. Distinct layers can be identified in mature forests.The canopy layer consists of trees 60 to 100 feet high, including mixed oaks, hickories, sugar maple,beech, birch, or other hardwoods, or hemlock and white pine. An understory layer 30 to 40 feet highhas trees such as dogwood, hornbeam, and saplings. Below this understory, a shrub layer about 3 to 4feet high, might include blackberry, arrowwood, spicebush, blueberry, or huckleberry. Poison ivy,Virginia creeper, and Japanese honeysuckle are vines that span all layers. An herbaceous (nonwoody)layer of perennial, annual, and biennial plants is found at the forest floor.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 39

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................T i m e L a p s eDescriptions of Plants and <strong>Animal</strong>sGrass/Herb: Grasses and herbs cannot tolerateexcessive shade. They grow quickly, but havenonwoody stems and do not reach a greatheight.Shrub: Shrubs have woody stems and areusually intermediate in height between grassesand trees. They can tolerate some shade.Sapling: Saplings are trees that have not reachedfull height. They may be the size of large shrubs.Mature tree: These trees have reached their fullheight and form the canopy layers.Songbird: Songbirds in this area live in maturetrees.Squirrel: Squirrels build their nests in treesbut are seen on the ground and moving throughtree branches. They eat fruit, berries, and nuts.Garter snake: This snake lives in grassy areasand shrubs. It eats toads, earthworms, smallbirds, and mammals.Toad: Toads live in meadows and shrub lands.They eat insects and other invertebrates.<strong>Wild</strong> turkey: Turkeys roost in trees and needclearings and brushy fields for nesting.Mouse: Mice live in burrows and eat berries,grains, and insects.Owl: Owls in this area nest in trees but huntthe ground for mice and shrews.Deer: Deer eat grasses, shrubs, and crops. Theyprefer an edge community where they canhide but also venture periodically into openareas to browse.Grasshopper: Grasshoppers live in grassy areasand eat grass, clover, and other herbs.Rabbit: Rabbits live in edge communities wherethere is plenty of shrub cover to hide, plusgrasses and other herbs to eat.Quail: Quail nest in shrub areas where theyhave cover, but they may feed in more open,grassy spaces that supply many insects.Sparrow: Sparrows nest in shrub and tree areaswhere they have cover but may feed in moreopen spaces that supply many insects.Cardinal: Cardinals are red to brownish-redbirds that nest in the high branches of shrubsor low branches of trees. They feed on berries,seeds, and insects gathered from plants or fromthe ground.Robin: Robins live in edge communities wherethere are open grassy spaces, shrubs, and smalltrees. They build their nests in the branchesof younger trees and eat berries, worms,and insects.Fox: Foxes live in burrows called dens. Theyprefer some ground cover for hunting, and theyfeed on birds, mice, rabbits, insects, and berries.Black bear: Bears live in the thick forest wherethey have plenty of cover. They eat a varietyof plant and animal matter.40 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................E c o s y s t e m F a c e l i f tStudent Guide PageThis guide may be given to the student groups as they are working on their designs to ensure that thediscussion points are incorporated into student learning.I. TopographyConsider the topography of your site.A. Locate hills.B. Locate lowlands.C. Locate sources of water.D. Locate areas of moist soils.E. Locate areas of dry soils.II. PlantsA. Using the following chart, decide which plants would be most suitable for the site when consideringthe plant’s requirements for space, soil, sunlight, water, and temperature:Plant Space Soil Sunlight Water TemperatureB. What improvements could be made to allow for a greater variety of species? (e.g., water sources?)C. Consider two plants having the same requirements. How will competition between them be handled?III. <strong>Animal</strong>sA. Using the following chart, decide which animals would be best suited for the site when consideringthe animal’s requirements for space, food, shelter, and water?<strong>Animal</strong> Space Food Shelter WaterB. What improvements could be made to allow for a greater variety of species? (e.g., water sources?)C. Consider two animals having the same requirements. How can this competition be avoided?IV. InteractionsA. Consider consumption of one organism by another. Can overpredation be avoided?B. Which plant communities will be best at supporting which animals?....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 41

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................E c o s y s t e m F a c e l i f tA 1,000-year flood has destroyed the plants and animals on Belle Island. The 20-acre island is in the middleof a tidal river. (Tidal rivers are open to the ocean and experience daily tidal fluctuations.) It hasa large hill on the ocean side of the island (the side affected by the tides), and there is a low area capableof sustaining a marsh on the opposite side of the island. The island also has a flat plain that was formerlya meadow. The island has been used in many different ways since Europeans settled the area; originally itwas used as a plantation. Later, industries powered by hydro-electricity were located on the island. Beforethe flood, the island was overgrown with a mixture of native and non-native plants and was inhabited bya variety of native and non-native wildlife.List of Native and Non-Native Species Originally Found on the IslandNativeNon-NativeNativeNon-NativeTreesRed oaksRiver birchPineVinesVirginia creeperTrumpet vinePoison ivyOther PlantsJack-in-the-pulpitCattails<strong>Wild</strong> riceTreesEmpress treeTree-of-heavenVinesJapanese honeysuckleKudzuOther PlantsCordgrassCrabgrassDandelionsPurple loosestrifeIsland ScenarioBelle Island<strong>Animal</strong>sAquatic turtlesFrogsSnakesRaccoonsDeerOpossumGreat blue heronOspreyCardinalDragonflyMayflyMosquitoBluegill<strong>Animal</strong>sStarlingsEnglish sparrowsPigeonsNorway ratsNutriaHouse catsStray dogsCarpStriped bassBelle Island42 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................E c o s y s t e m F a c e l i f tShopping Center ScenarioAcme AcresAn abandoned shopping area is being torn down to make room for a new park. The area is currently20 acres of asphalt and concrete that has been neglected for more than 10 years.The city would like to develop a complete working ecosystem that benefits the people of the communityby providing a natural setting that will attract wildlife. Different community needs and uses for the sitehave been identified and are being suggested to the city planning committee. Community memberssaid that whatever the site is used for, the ecosystem that is established on the site must be healthyand sustainable.List of Urban Species Normally Found in Surrounding SitesTreesEmpress treeTree-of-heavenElmVinesJapanese honeysuckleEnglish ivyPoison ivyOther PlantsCrab grassDandelionsMilkweedLily of the valley<strong>Animal</strong>sStarlingsEnglish sparrowsPigeonsNorway ratsHouse catsStray dogsCarp/GoldfishCrowsRaccoonsGray squirrelsBatsMosquitoesAntsAcme Acres....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 43

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................B o t t l e n e c k G e n e sKey to Genetic CharacteristicsYellowBlackOrangePinkDark blueGreenPurpleRedWhitecamouflageprecise visionaccurate sense of smellstrong claws and forearmshealthy jaw formationagilityacute hearinghealthy rate of reproductionimmunity to canine distemper44 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................B o t t l e n e c k G e n e sKey to Environmental Situations1. A farmer has been trying to protect hiswheat fields by exterminating prairie dogs.Very little prey is available. Given thegenetic makeup, how would yourpopulation survive?2. A golden eagle hunts from high above andwill prey on available animals such as theblack-footed ferret. Does your populationhave the gene for precise vision to avoidbeing captured? Given the genetic makeup,how would your population survive?3. Black-footed ferret kits disperse from theirhome territory and are able to establishnew populations in nearby prairie dogtowns. Given the genetic makeup, howwould your population survive?4. An interstate highway has been built nearyour prairie dog town. How does this roadaffect your black-footed ferret population?Given the genetic makeup, how wouldyour population survive?5. Ranchers are allowing their dogs to runloose. Will your population’s genes protectit against canine distemper, assuming thedogs carry it? Given the genetic makeup,how would your population survive?6. A new generation of captive-born blackfootedferret kits has been preconditionedto live in the wild and are ready to bereleased at a nearby reintroduction site.Given the genetic makeup, how wouldyour population survive?7. A plague has hit your prairie dog town,and most of the prairie dogs die from thedisease. How does your black-footed ferretpopulation adapt to a reduction in foodsupply? Given the genetic makeup, howwould your population survive?8. As a coyote silently prowls nearby, only itsodor might warn of its presence. Does yourpopulation have the gene for an acute senseof smell to warn about the coyote?9. Black-footed ferrets eat prairie dogs and useprairie dog burrows for shelter. Does yourferret population have the agility gene tocatch an aggressive prairie dog in its dark,narrow, winding tunnel system? Given thegenetic makeup, how would your populationsurvive?10. Black-footed ferrets are nocturnal creaturesthat leave their burrows at night to feed.Does your ferret population have the camouflagegene to keep well hidden from thegreat horned owl hunting for its dinner?Given the genetic makeup, how wouldyour population survive?11. A badger is moving quietly around theprairie dog town. Does your populationhave the gene for acute hearing to avoid thispredator? Given the genetic makeup, howwould your population survive?12. A prairie dog colony has just been establishedin a state park only a few miles away.How does the colony affect your populationsof ferrets? Given the genetic makeup,how would your population survive?13. It will be difficult for your population totake over and adapt to prairie dog burrowswithout the gene for strong claws andforelegs. Given the genetic makeup, howwould your population survive?14. Humans who are building homes havewiped out a prairie dog town 10 milesaway. The surviving black-footed ferretsfrom that area are moving into your territory.Given the genetic makeup, how wouldyour population survive?....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 45

E c o l o g i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................B o t t l e n e c k G e n e sBlack-Footed Ferret Bottleneck ScenarioNames of Team Members_____________________________________________________On your Key to Genetic Characteristics, circle the COLORS and GENES that your populationreceived through the bottleneck.1. Calculate the percentage of genetic diversity (heterozygosity) of your population.Nine genes (colors) represent 100 percent genetic diversity in the original population._________ genes received ÷ 9 original genes = _________(decimal) x 100 = ________%2. List the genetic characteristics (colors) that your population received throughthe bottleneck.3. List the genetic characteristics that your population lost when it came throughthe bottleneck. (colors not received)4. Using the five environmental situations, write a prediction about what will happen toyour population during the coming year.Is the population genetically equipped to survive in its environment? How well or howpoorly? How does a high or low percentage of genetic diversity affect the population’ssurvival? How do random changes in the environment affect the population?46 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................A n d t h e W o l f W o r e S h o e sSHELTERAPPEARANCEACTIONSFOODLOCOMOTIONIMAGINARY REAL....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 47

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................M u s e u m S e a r c h f o r W i l d l i f eMuseum Search for <strong>Wild</strong>life ChartPlace a check after the name of the animals found on the Museum Search for <strong>Wild</strong>life.<strong>Animal</strong> Group Domestic <strong>Animal</strong>s (Tame) <strong>Wild</strong>life (Untamed)48 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................P r a i r i e M e m o i r sPrairie MemoirsMemoir I:From the Stories of Johnny KincaidI was a scrawny kid who’d come to the Great Plainsfrom Chicago looking for wealth and adventure inthe spring of 1870. I didn’t know what I would dowhen I got there, but I knew I would do somethingadventurous. When I arrived in Dodge City, I waspenniless, tired, and hungry. I wandered the street,alone and scared. A huge man, about 6′4″ with armsas big as two men and shoulders of steel, saunteredup to me. He wore buckskins and had a rifle flungacross his shoulder. I was impressed.He introduced himself as Sure Eye Jones (to thisday, I do not know his real name). He asked if I waslooking for work. He explained that he needed askinner to go with him on a hunt the next day. Hesaid he’d cover all my grub and pay me handsomelyfor each buffalo hide. I didn’t know at that timewhat a skinner was, but it sounded like a good dealto me. Besides, I was desperate.We headed out into the prairie land the next daylooking for the big herd. Another man named DougMcKinnon, who was an experienced skinner, camealong. He promised to teach me all he could aboutskinning. He gave me both a long bowed knife tohang on my hip and another short knife, somethinglike a dagger, to strap on my boot. They were sharpenough to cut paper. Doug explained skinning tome while we searched for the herd. He told me wewould prepare the hides for sale back in Dodge Cityand that my earnings would depend upon how manyanimals I could skin in a day. The more I did, themore money I would make.As we traveled, I became excited about the huntand the thought of making money. We came overthe crest of a hill and saw the buffalo below us. Itwas a huge herd that covered the open plain as faras the eye could see. Some were young, some werecalves, and some were heavy with young not born.It was an amazing sight. As my eyes lingered on theherd, a crack rang out in the air as a bullet shot intothe herd and took out a yearling, which Doug whisperedto me would be our dinner for the next fewdays. Sure Eye (now I realized how he got his name)took aim again and shot another. Crack after crackof the rifle rang out as Sure Eye killed buffalo afterbuffalo. It wasn’t until he had killed 30 or so thathe stopped.Doug hollered at me to “Move it!” We raced downthe hill and began our work. It took us all day andlate into the night before we had skinned all thedead animals. Sure Eye came by and said, “Welldone, boy! As far as I can figure, you just madeyourself a whole heap of money. Well done.”He slapped me on the back and moved on backto camp.I continued to skin buffalo until there were no moreto be found. I earned a great deal of money and wasable to return to Dodge City to build a home; marrymy wife, Sally; and work in town.Some days I miss those grand herds of buffalostretching across the horizon. It was quite anadventure, those early days on the prairie.....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 49

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................P r a i r i e M e m o i r sMemoir II:From the Stories of Gray HawkBack in the days when the Earth was new, myforefathers hunted buffalo on foot. The buffaloflesh provided my people with food, and the skinbecame clothing and the sheltering cover of tepees.My people’s daily life revolved around the buffalohunt, and our rituals and worship were dedicatedto its success.Then the Spaniards brought horses, and many ofthese animals wandered over the plains. My peoplelearned to tame and ride these wild animals. Webecame great horsemen. The horse allowed us tobecome great hunters; it helped us follow the buffaloherds. We also crafted tools to help us hunt. Hunterscarried a short bow, a quiver for barbed arrows, anda long shear. Because the hunters were able to ridewith hands free, they could feed and release the bow,and the hunts became more and more successful.With the horse, our tribe was able to follow thebuffalo and have a steady supply of food. The tribegrew. Often, small hunting groups would leave thelarger tribe, but each summer all our people wouldreunite for the sacred ritual dance. This ritual lastedfour days in which we honored the buffalo withofferings and ceremonial dances. Our dance celebratedthe natural cycle of the grass, the soil, and thebuffalo. We honored the buffalo, for it provided uswith our daily needs.The buffalo herds began to grow smaller. We hadbecome skillful hunters, and settlers came to live onour land, build railroads, and hunt buffalo. The buffalocould not survive; the natural cycle had beenchanged. Then the settlers’ government told my peoplewe had to change our ways. We were told whereto live and that we could not continue to follow thebuffalo herds. The fact was that thebuffalo herds were gone and that the ways of ourancestors would continue only in our stories.........................................................................................................Memoir III:From the Diary of Catherine O’RileyEarly in the year of 1860, my husband and I leftthe forest lands of Missouri for the tall grass prairieof the area now known as Oklahoma. Our dreamwas to build a cattle ranch in this fertile grassland.We had been told that this was a wild area, but itwas also rich in opportunity. However, in this landwithout trees, building a house, corrals, and barnsbecame a problem. Providing water proved to be aneven more difficult task. We soon knew that survivalin this new land would require us to be strong andself-sufficient.The first years on the ranch were tough. We werenot prepared for what happened the first time aherd of buffalo moved into our cattle grazing area.The buffalo were large, aggressive animals, and thecattle scattered in fright. The buffalo depletedthe grass and rolled in the dirt, creating great dustclouds. These large animals trampled anything thatgot in their path, and constructing barriers did nothingto change their course. Along with the buffalocame the native tribes. Many tribes had been relocatedto the Oklahoma Territory, but they did notalways stay on their reservation lands.We thought the U.S. government with the soldiersfrom the area forts would make sure the tribesstayed on the land they were given. The government,however, was fighting a civil war. The only soldiersthat we had to protect us and our property wereuntrained recruits, and they caused more problemsthan they solved. Many ranchers in the area met todiscuss a way to handle the problem of the roamingherds of buffalo and the roaming tribes.Someone had heard about the buffalo hunters hiredby the railroad. Supporting these buffalo huntersseemed a good way to remove the threat of theseanimals. It was also suggested that if the tribes stayedon the reservations, the government could providethem with cattle. Then they would not need thebuffalo, and we would have a new market for ouranimals. However, it was obvious that it was up tous to protect our property and livelihood.By 1890, the buffalo and the native tribes wereremoved from the plains, and cattle freely grazedon the lush grass of the open public range. The bestcows and bulls were kept and the breeds constantlyimproved. For the next few years, ranching was oneof the most profitable industries in the country.50 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................P o w e r o f a S o n gTo Be <strong>Wild</strong>....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 51

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................F o r Y o u r E y e s O n l yFactors That Influence Attitude/Viewpoint Toward the Environmentpoliticaleconomicreligiousecologicalscientificculturaleducationalaestheticsocialrecreationalegocentrichealth-relatedethical/moralhistoricalpertains to the role or position of a governmental agencypertains to uses for food, clothing, shelter, and other benefitspertains to faithpertains to roles in maintaining a natural ecosystempertains to providing an understanding of biological functionspertains to societal customs, beliefs, and lawspertains to providing an understanding of a species and ofthe role people play in the environmentpertains to sources of beauty and inspirationpertains to shared human emotions and statuspertains to providing leisure activitiespertains to a focus on human benefit of resourcepertains to positive human conditionspertains to responsibilities and standardspertains to connections to the past52 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................F o r Y o u r E y e s O n l yQuotable Quotes“I am against nature. I don’t dig nature at all. I thinknature is very unnatural. I think the truly naturalthings are dreams, which nature can’t touch withdecay.”Bob Dylan (1986)“After you have exhausted what there is in business,politics, conviviality, and so on—have found thatnone of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear—what remains? Nature remains.”Walt Whitman (1882)“There are those who look at Nature from the standpointof conventional and artificial life—from parlorwindows and through gilt-edged poems—the sentimentalists.At the other extreme are those who donot look at Nature at all, but are a grown part of her,and look away from her toward the other class—thebackwoodsman and pioneers, and all rude and simplepersons. Then there are those in whom the two areunited and merged—the great poets and artists. Inthem, the sentimentalist is corrected and cured, andthe hairy and taciturn frontiersman has had experienceto some purpose. The true poet knows moreabout Nature than the naturalists because he carriesher open secrets in his heart.”John Burroughs (1906)“Man masters nature not by force but by understanding.This is why science has succeeded where magicfailed: because it has looked for no spell tocast over nature.”Jacob Bronowski (1953)“Of all the things that oppress me, this sense of theevil working of nature herself—my disgust at herbarbarity, clumsiness, darkness, bitter mockery ofherself—is the most desolating.”John Ruskin (1871)“You may drive out nature with a pitchfork, yet she’llbe constantly running back.”Horace (8 B.C.)“To sit in the shade on a fine day and look uponverdure is the most perfect refreshment.”Jane Austin (1814)“There is in every American, I think, something ofthe old Daniel Boone—who, when he could seethe smoke from another chimney, felt himself toocrowded and moved further out into the wilderness.”Hubert H. Humphrey (1966)“In a few generations more, there will probably beno more room at all allowed for animals on theearth: no need of them, no toleration of them. Animmense agony will have then ceased, but with itthere will also have passed away the last smile of theworld’s youth.”Ouida (Marie Louise de la Ramee) (1900)“Nature has no mercy at all. Nature says, ‘I’m goingto snow. If you have a bikini and no snowshoes,that’s tough. I am going to snow anyway.’”Maya Angelou (1974)“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in theeyes of others only a green thing that stands in theway. Some see nature all ridicule and deformity …and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes ofthe man of imagination, nature is imagination itself.”William Blake (1799)“The Laws of Nature are just, but terrible. There isno weak mercy in them. Cause and consequenceare inseparable and inevitable. The elements haveno forbearance. The fire burns, the water drowns, theair consumes, the earth buries. And perhaps it wouldbe well for our race if the punishment of crimesagainst the Laws of Man were as inevitable as thepunishment of crimes against the Laws of Nature—were Man as unerring in his judgments as Nature.”Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1857)“One swallow does not make a summer, but oneskein of geese, cleaving the murk of a March thaw,is the spring. A cardinal, whistling spring to thawbut later finding himself mistaken, can retrieve hiserror by resuming his winter silence. A chipmunk,emerging for a sun bath,but finding a blizzard, hasonly to go back to bed. But a migrating goose, staking200 miles of black night on the chance of findinga hole in the lake, has no easy chance for retreat. Hisarrival carries the conviction of a prophet who hasburned his bridges.”Aldo Leopold (1970)....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 53

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................E t h i - R e a s o n i n gDilemma CardA deer herd has grown so large during the past10 years that many of the deer appear to be starving.The herd is severely damaging the habitat,eliminating much of the vegetation that the animalsuse for food or shelter. There is adisagreement within your community as to whatcourse of action is best to take. You personally areopposed to hunting. A limited legal hunt has beenproposed to reduce the size of the herd in thisarea. Would you:Dilemma CardYou are a homeowner in an area directly abovea city. Local government officials have proposeddiverting a small stream from the property ofseveral homeowners above the city, includingyours, to power a hydro-electric system that willbenefit the entire city. As a homeowner, you areconcerned with losing the aesthetic values of thisstream from your property. You also are concernedabout the effect the removal of this streamwill have on the fish and aquatic habitat. Another• Investigate and consider the situation to see concern is that your property may lose some ofwhat, in your judgment, seems the mostits value for resale. You realize that your cityhumane and reasonable solution, including the needs to supply electric power to all its citizensfeasibility of options such as moving some as cost-effectively as possible. Would you:deer to other areas, even though you understandthat they still may not survive?• Hire a lawyer and prepare to sue the city forloss of property value?• Attempt to identify the causes of this• Form a coalition of homeowners to meet withpopulation increase and propose action tocity planners and explore possible alternatives?return the system to a balance?• Sell your property before the project is begun?• Allow the habitat degradation to continue• Decide the needs of the city are moreand the deer to starve?important than either the consequences to• Leave it to the state wildlife agency to workyou personally or the ecological costs?with the landholder to arrive at a solution?• Do something else?• Do something else?........................................................................................................Dilemma CardDilemma CardYour family owns a 500-acre farm. A tributaryto a high-quality fishing stream runs along theboundary of your property. The nitrogen- andphosphorous-based fertilizer that your familyuses to increase crop production is carried intothe stream by rain run-off. This type of fertilizeris increasing algae growth and adversely affectingthe fish population in both the tributary and themain stream. Your farm production is your solesource of income, but your family has alwaysenjoyed fishing and doesn’t want to lose the fishfrom the streams. Would you:• Change fertilizers even though it may reducecrop yield?• Allow a portion of your land along the streamto grow wild, thus establishing a buffer zone(riparian area)?• Investigate the possibility of gaining a taxexemption for the land you allowed for abuffer zone?• Do nothing?• Do something else?You are a farmer. You have been studying andhearing about farming practices such as leavingedge areas for wildlife, no-till farming, and organicpest control. Although these practices mayimprove your long-term benefits, they mayreduce your short-term profits. You are alreadyhaving trouble paying your taxes and keeping upwith expenses. Would you:• Sell the farm?• Keep studying farming practices but make nochanges for now?• Try a few methods on some of your acreage,and compare the results with other similarareas on your land?• Do something else?54 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages............................................................................................................................................

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................E t h i - R e a s o n i n gDilemma CardYou are fishing at a secluded lake and have caught2 fish during your first day at the lake. Now, onthe second day, the fishing has been great, andyou have caught 5 fish in the first hour, all ofwhich are bigger than yesterday’s fish. The lawDilemma CardYou are finally able to build your family’s dreamhouse. Because of rising construction costs, yourealize that you cannot include all the featuresyou had planned for. You must decide which oneof the following you will include:allows you to possess 12 fish. Would you:• solar heating,• Continue to fish and keep all the fish?• recreation room with fireplace,• Dispose of the smaller fish you caught• hot tub and sauna,yesterday, and keep the big ones to staywithin your limit?• greenhouse, or• Have fish for lunch?• something else.• Quit fishing and go for a hike?• Do something else?........................................................................................................Dilemma CardDilemma CardYou are a member of a country club that hasrecently voted to build a wildlife farm to raiseanimals for members to hunt. You are not ahunter, you think that hunting is okay only to doin the wild, and you are opposed to building thewildlife farm. Would you:• Stay in the club and do nothing?• Stay in the club, and speak out strongly againstthe subject?• Resign from the club?• Do something else?............................................................................................................................................You are an influential member of the community.On your way home from work, you are stoppedby a police officer and cited for having excessiveauto emissions. Would you:• Use your influence to have the ticketinvalidated?• Sell the car to some unsuspecting person?• Work to change the law?• Get your car fixed and pay the ticket?• Do something else?........................................................................................................Dilemma CardYour class is on a field trip to the zoo. Althoughyou know that feeding of animals by zoo visitorsis prohibited, some of your friends are feedingmarshmallows to the bears. Would you:Dilemma CardYou are on a picnic with your family and yousee members of another family leaving to gohome without picking up their trash. It is clearthe other family is going to leave litter all around.• Tell them that feeding marshmallows may Would you:harm the bears, and ask them to stop?• Move quickly, and ask them to pick up their• Report their behavior to the nearesttrash before they leave?zoo keeper?• Wait for them to leave, and pick up the trash• Ask the teacher to ask them to stop?for them?• Do nothing?• Do nothing?• Do something else?• Do something else?....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 55

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................E t h i - R e a s o n i n gDilemma CardYou are walking in the woods and come upona young fawn. There is no sign of the fawn’smother. Would you:Dilemma CardYou love children and would like to have a largefamily. You are aware, however, of the world’spopulation projections for the future. Would you:• Leave the fawn where it is?• Plan to have a large family anyway?• Move the fawn to a sheltered area?• Decide not to have children?• Take the fawn home?• Limit yourself to one or two children?• Do something else?• Do something else?........................................................................................................Dilemma CardDilemma CardYou have found a young screech owl and raised itto maturity. You have been told that you cannotkeep the owl any longer because keeping it withoutthe proper permit violates state andfederal laws. Would you:• Offer it to your local zoo?• Keep it as a pet?• Call members of the local fish and wildlifeagency and ask their advice?• Determine whether it could survive in thewild; if it appears the owl could, release itin a suitable area?• Do something else?You are out in the woods with a friend when youspot a hawk perched on a high limb. Before yourealize what is happening, your friend shoots thehawk. An hour later, you are leaving the woodsand are approached by a state wildlife officerwho tells you a hawk has been illegally shot andasks if you know anything about it. Would you:• Deny any knowledge of the incident?• Admit your friend did it?• Make up a story implicating someone else?• Say nothing, but call the fish and wildlife officerlater with an anonymous phone tip?• Do something else?........................................................................................................Dilemma CardYou are president of a large corporation. You arevery interested in pollution control and have hada task force assigned to study the pollution yourplant is creating. The task force reports that youare barely within the legal requirements. Theplant is polluting the community. To add thenecessary equipment to reduce pollution wouldcost so much that you would have to fire 50employees. Would you:Dilemma CardYou have purchased a beautiful 10-acre propertyin the mountains to build a summer home. Onehillside of the property has a beautiful view ofthe valley and lake below and is your choice foryour home site. However, you discover an activebald eagle has a nest site on that hillside. The baldeagle is sensitive to disturbance around its nesttree and is a protected species. Bald eagles arehighly selective in choosing nest sites and• Add the equipment, and fire the employees? usually return to the same nest year after year.Would you:• Not add the equipment?• Select a different site on the property to build• Wait a few years to see if the cost of theyour home?equipment will drop?• Sell the property?• Hire an engineering firm to provide furtherrecommendations?• Chop down the tree and build your home?• Do something else?• Do something else?56 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages............................................................................................................................................

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................W i l d l i f e o n C o i n s a n d S t a m p s....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 57

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................P a y t o P l a yActivityNumber of Participants forThree <strong>Wild</strong>life-Associated Activities1970 versus 19961970 1996Fishing 33,000,000 35,200,000Hunting 14,000,000 14,000,000<strong>Wild</strong>life Watching 38,200,000 62,900,000Total 85,000,000 112,100,000Source:“1970 National Survey of Fishing and Hunting” and the “1996 National Survey of Fishing and Hunting and <strong>Wild</strong>life-AssociatedRecreation,” published jointly by the U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and <strong>Wild</strong>life Service, and U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureauof the Census.58 ....................................................................................................<strong>Project</strong> WILD K–12 Curriculum and Activity Guide Student Pages

S o c i a l a n d P o l i t i c a l K n o w l e d g e........................................................................................................P a y t o P l a yActivity <strong>Cards</strong>CONSUMPTIVEWILDLIFEMANAGEMENTFACTOR• Good fortune! You have won first prize in a fishing contest. Collect $50 fromthe Public Bank if you have a fishing license.Most states maintain a number of fish hatcheries to stock public fishing areas.Transfer $25 from the <strong>Wild</strong>life Management Fund to the Public Bank.(Keep this card if you have a fishing license.)CONSUMPTIVEWILDLIFEMANAGEMENTFACTOR• Dry weather and poor forage have reduced the deer population in your huntingarea. You must buy your meat this year. Pay $150 to the Public Bank.Deer management involves aerial surveys, habitat protection and improvement,and law enforcement. Transfer $50 from the <strong>Wild</strong>life Management Fund to thePublic Bank.(Keep this card.)CONSUMPTIVEWILDLIFEMANAGEMENTFACTOR• You just caught your favorite lure on a submerged stump. Pay $5 to thePublic Bank for a replacement.There is a federal tax on fishing gear that helps pay for sportfish restoration.Transfer $50 from the Public Bank to the <strong>Wild</strong>life Management Fund.(Keep this card if you have a fishing license.)CONSUMPTIVEWILDLIFEMANAGEMENTFACTOR• You spend most of the day collecting firewood that was used to cook thedelicious fish you caught. Your energy level is so high that you get to takeanother turn if you have a fishing license.The trees for your firewood are a renewable resource that benefits both wildlifeand people. For forest management, transfer $25 from the <strong>Wild</strong>life ManagementFund to the Public Bank.(Keep this card if you have a fishing license.)....................................................................................................© Council for Environmental Education 2004 59