96- Rafal Gan-Ganowicz. Polish Hero Of Yemen

96- Rafal Gan-Ganowicz. Polish Hero Of Yemen

96- Rafal Gan-Ganowicz. Polish Hero Of Yemen

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

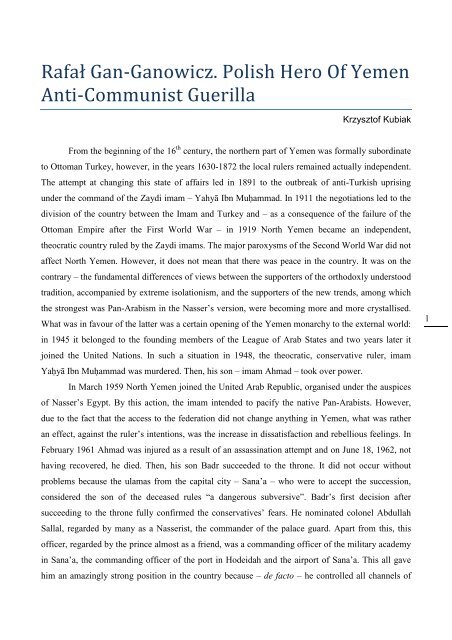

Rafał <strong>Gan</strong>-<strong>Gan</strong>owicz. <strong>Polish</strong> <strong>Hero</strong> <strong>Of</strong> <strong>Yemen</strong>Anti-Communist GuerillaKrzysztof KubiakFrom the beginning of the 16 th century, the northern part of <strong>Yemen</strong> was formally subordinateto Ottoman Turkey, however, in the years 1630-1872 the local rulers remained actually independent.The attempt at changing this state of affairs led in 1891 to the outbreak of anti-Turkish uprisingunder the command of the Zaydi imam – Yahyā Ibn Muḥammad. In 1911 the negotiations led to thedivision of the country between the Imam and Turkey and – as a consequence of the failure of theOttoman Empire after the First World War – in 1919 North <strong>Yemen</strong> became an independent,theocratic country ruled by the Zaydi imams. The major paroxysms of the Second World War did notaffect North <strong>Yemen</strong>. However, it does not mean that there was peace in the country. It was on thecontrary – the fundamental differences of views between the supporters of the orthodoxly understoodtradition, accompanied by extreme isolationism, and the supporters of the new trends, among whichthe strongest was Pan-Arabism in the Nasser’s version, were becoming more and more crystallised.What was in favour of the latter was a certain opening of the <strong>Yemen</strong> monarchy to the external world:in 1945 it belonged to the founding members of the League of Arab States and two years later itjoined the United Nations. In such a situation in 1948, the theocratic, conservative ruler, imamYaḥyā Ibn Muḥammad was murdered. Then, his son – imam Ahmad – took over power.In March 1959 North <strong>Yemen</strong> joined the United Arab Republic, organised under the auspicesof Nasser’s Egypt. By this action, the imam intended to pacify the native Pan-Arabists. However,due to the fact that the access to the federation did not change anything in <strong>Yemen</strong>, what was ratheran effect, against the ruler’s intentions, was the increase in dissatisfaction and rebellious feelings. InFebruary 1<strong>96</strong>1 Ahmad was injured as a result of an assassination attempt and on June 18, 1<strong>96</strong>2, nothaving recovered, he died. Then, his son Badr succeeded to the throne. It did not occur withoutproblems because the ulamas from the capital city – Sana’a – who were to accept the succession,considered the son of the deceased rules “a dangerous subversive”. Badr’s first decision aftersucceeding to the throne fully confirmed the conservatives’ fears. He nominated colonel AbdullahSallal, regarded by many as a Nasserist, the commander of the palace guard. Apart from this, thisofficer, regarded by the prince almost as a friend, was a commanding officer of the military academyin Sana’a, the commanding officer of the port in Hodeidah and the airport of Sana’a. This all gavehim an amazingly strong position in the country because – de facto – he controlled all channels of1

external communication.A Coup D’étatBadr, residing in Sana’a, did not obviously have the political craftiness of his father and he did notfigure out that at the same time four plots were organised against his rule. Two of them grew in themilitary forces: the first one was commanded by captain Ali Abdul al Moghny and the other one – bycolonel Sallal. These were the typical officers’ conspiracies. The third plot was organised by themembers of the tribal group – the Hashid – who were trying to take their revenge for executing – onthe order of Ahmad – their charismatic sheik and his son. The fourth plot was prepared by theyounger sons of the clan elders who were simply trying to provide themselves with various benefitsby means of placing someone from their generation on the throne. It seems that the only personfamiliar with this network of intrigues was the Egyptian chargé d'affaires – Abdul Wahad. He actedon the basis of the confidential instructions telling to support the other groups supporting Egypt inthe <strong>Yemen</strong> Pan-Arabian opposition.The Egyptian was afraid that the conspirators would not have enough will, courage anddetermination in order to carry out the coup d’état and therefore then he became involved in theamazingly complex conflict. Twenty four hours before the planned putsch, he informed Badr that thearmy was planning an action against him. The next step was to inform the conspirators that theirintentions had been discovered and that only outdistancing the action of the forces faithful to themonarch could save them from arresting. In this way, “the die was cast”.Sallal and other plotters were in essence deprived by the Egyptian intrigue of any room formanoeuvre. On the morning of September 25, the colonel put the students of Military Academy intobattle readiness. In this academy the influences of conspirators were particularly strong and that iswhy the colonel attempted to inform the other members of officer conspiracies of the beginning ofthe action. However, captain Moghny, another officer involved in the intrigue and the commandingofficer of the armoured division stationed in Sana’a, acted faster. The main objects of the assassins’actions were typical of the situation – they intended to capture the Badr’s seat, the arsenal, the policeheadquarters, the building of the ministry of foreign affairs, the radio station, the telephone centraloffice and the airport as soon as possible.On September 25, around 09.00 Moghny started his “revolution”, leading 13 tanks, sixarmoured cars, two self-propelled guns and two towed anti-tank heavy guns onto the imam’s palace.Around 10.30 Badr heard the rattle of the armoured tanks and started to blindly fire a machine gunthrough the window of his palace. The plotters opened fire several dozen minutes later when the2

attempts at urging the palace guard to leave the ruler ended in a fiasco. The fight for the Badr’spalace lasted almost twenty four hours.The Egyptian interventionBadr, along with his faithful servants, managed to escape from the palace through the adjacentgarden. There was only one way of the escape for the overthrown imam – to Saudi Arabia. In themeantime, on September 28 colonel Sallal, who headed the Revolutionary Command Council,announced to the tribe chiefs gathered in the capital city that Badr had been killed. In practice, itmeant the death penalty for the imam. On September 29, a personal emissary of Nasser – general AliAbdul Hameed – arrived in <strong>Yemen</strong> with the task of becoming familiarised with the local situation.Sallal immediately asked him to send the Egyptian soldiers since the officers incited to rebellionclearly did not trust their subordinates. Cairo took a positive position to this request. Already onOctober 05, the first subunits of the Egyptian special-purpose battalion arrived in Hodeidah. Thecommandoes took responsibility for the personal protection of Sallal and other prominent figures ofthe new regime.Taking over power in the country by the officers regarded as Nasserists did not bring aboutcommon enthusiasm. The conservative tribe elders, despite the fact that they were frequently inconflict with the imam, were of the – fully justified – opinion that the monarchy was a lesser threatto their power than the military radicals. Saudi Arabia – a great neighbour of <strong>Yemen</strong> – whose rulersdid not intend to accept the centre of Pan-Arabism in the vicinity of their borders – was alsointerested in the failure of the coup d’état. The common interests of the Saudi Arabians and the<strong>Yemen</strong> monarchists (in spite of the fact that the former were orthodox Sunnis whereas the latter –“Zaydi heretics”) could not have been not consummated in such a situation. Already betweenOctober 02 and October 08, the tribes from north-western <strong>Yemen</strong> received at least four air transportsof weapons from Saudi Arabia. The army of the Saudi Arabians occupied at the same time thepositions along the border with the southern neighbour. This, in turn, triggered off the reinforcementof the Egyptian contingent in <strong>Yemen</strong>: after the first battalion, the other came; in a short period oftime, there were as many as 18 000 Egyptian soldiers in <strong>Yemen</strong>.The arrival of the Egyptian army in <strong>Yemen</strong> and locating the Saudi Arabian army along theborder as well as the support the monarchists received from Riyadh led to the increase in tension inthe whole area especially because the <strong>Yemen</strong> royalists (known as malakhi from the word malekhmeaning “a king”) started with great intensity the activities against the Egyptians.The success of the guerrillas totally depended on the Saudi Arabian support. Many officers3

and soldiers of the Saudi Arabian National Guard served voluntarily as well as on their superiors’orders in the royalist army. The Saudi Arabians also allowed the <strong>Yemen</strong> labourers, who came to theircountry before the coup d’état, to join the imam’s units; they also turned a blind eye to crossing theborder and joining the fight by the nomads from the South West who were strictly connected withthe <strong>Yemen</strong> tribes. Pakistan provided the imam’s forces with weapons whereas Iran and Iraq – withmoney. The British and Pakistani involvements were also quite significant.In such a situation, the Egyptian forces (maximally 55 000 soldiers) and the <strong>Yemen</strong>formations supporting the Egyptian forces could not achieve success. The hit-and-run tactics war,known as “the Egypt’s Vietnam”, lasted until 1<strong>96</strong>7 when – during the six-day war – the last 15 000soldiers were withdrawn to the country. Then, the Egyptians’ role was taken over by the Soviets(approximately 4 000 advisors and instructors).The withdrawal of the Saudi Arabian help determined the royalists’ failure. In 1970 SaudiArabia officially acknowledged the <strong>Yemen</strong> Arab Republic and the situation of the royalists becamevery difficult in spite of the fact that they had not lost the war and the republicans had not won it.However, ultimately the majority of the imam’s supporters found their way onto the republican side.Only the overthrown ruler and his close friends decided to emigrate to Great Britain. Thecompromise then accepted meant – when a different point of view it taken – that the Shia Zaydis,after a hundred years of ruling <strong>Yemen</strong>, were definitely removed from power. In this context, the onlywinner of the civil war in North <strong>Yemen</strong> seems to be Saudi Arabia.4The <strong>Polish</strong> guerrilla of the imamThe later <strong>Polish</strong> guerrilla of imam Badr was born in 1932 near Wawer in the vicinity of Warsaw. Hisfather, originating from the noble family of <strong>Polish</strong> Tatars settled in Lithuania at the beginning of the16 th century by Grand Duke Vytautas, was a very colourful and picturesque figure. He served in theFrench Foreign Legion and then he looked for fortune in South America being engaged, amongothers, in gold mining and investing in the plantation of rubber in Brazil. <strong>Gan</strong>owicz the father usedRawicz coat of arms which was later to be treated by his son as a surname-pseudonym, under whichhe cooperated with Radio Free Europe.In 1939, during the <strong>Polish</strong> September Campaign initiating the Second World War, <strong>Gan</strong>owiczlost his mother killed by an accidental German shot. Rafał’s father moved then from Wawer to theWarsaw district of Żoliborz where he lived in the house belonging to his family. There, on August01, 1944 he experienced the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising. Then the older <strong>Gan</strong>owicz joined theinsurrectionists and soon he was killed. Rafał survived until the capitulation of the uprising and then

he avoided being deported to Germany by escaping from the Nazi transport.In the next years – the boy-orphan resided in various protection institutions. However, theexperience which shaped his consciousness more than the war with Germany and Nazi occupationwas the contact with the Red Army marching from the east and the communist power imposed uponPoland “with the Soviet bayonets”. <strong>Gan</strong>owicz and the people from his closest environment, partiallyoriginating from the pre-war middle class families, educated in the tradition of <strong>Polish</strong> victory in thewar with the Soviets in 1920, were not able to accept the new order which meant enslavement.At the end of the forties – so in the period of the height of the Stalinist terror, <strong>Gan</strong> <strong>Gan</strong>owiczbecame involved in the activity of one of the school conspiracy organisations 1 . Initially, thisorganisation dealt mainly with the distribution of leaflets. What should be stressed here is that suchactions were very seriously treated by the authorities who countered them ruthlessly. It happenedfrequently that the officers did not even try to apprehend the suspects but they acted in such a waythat they could liquidate them in the “attempt” at arresting. Terror was raging, there were cases inwhich the people unwanted by the authorities got lost, the courts of general jurisdictions passedsentences with death penalty for the acts of disobedience to the regime. In connection with theabove, the <strong>Gan</strong>owicz’s group made a successful attempt at obtaining weapons by means of disarmingpolice officers and soldiers and the next actions of distributing and pasting the leaflets were protectedby a member of the organisation who had a gun at his disposal.In 1950 the Security <strong>Of</strong>fice picked up the trail of the organisation; the activists started to bearrested. Having found out about this, <strong>Gan</strong>owicz made a decision to escape from Warsaw toWrocław – to the so-called “regained territories” where the massive migrations of people seemed tomake it easier to lose the pursuit. However, in the end, at the Wrocław railway station, in great partby accident, he found a Soviet train with the supply for the army stationed in the eastern zone ofBerlin and, hidden under the carriage platform with a gun in his belt, he left Poland.In Germany, <strong>Gan</strong> <strong>Gan</strong>owicz entered the group of <strong>Polish</strong> emigration encompassing thesoldiers of the <strong>Polish</strong> Military Forces in the West and the 1939 prisoners of the war who did notcome back to the country because of the fear of the communist terror as well as the refugees whomanaged to get through “the Iron Curtain” already after the regime, which enjoyed trust and supportof the Soviet Union, took over full power. The camp in which he was placed was situated in theAmerican sector. The young man was then under the overwhelming influence of people with51 What should be emphasised here is that at the turn of the forties and the fifties in Poland, according to theofficial data of the Security <strong>Of</strong>fice, there were 1236 youth anti-communist underground groups consisting ofover 20 000 members. Cf. K. Krajewski, 20 tysięcy Orląt, [in:] Historia antykomunistycznego podziemianiepodległościowego, supplement to Rzeczpospolita daily, no. 8 of May 18,2011, pp. 8-9.

crystallised, anti-communist views and it might be thought that this contributed to the strengtheningof the convictions with which he arrived from Poland.Still in Germany, <strong>Gan</strong> <strong>Gan</strong>owicz started his service in the <strong>Polish</strong> Guard Companies organisedby the American armed forces which were stationed in Belgium, France and Germany 2 . In thisformation, the teaching, educational and cultural activity was pursued; moreover, there were Englishlanguage classes (from 1949 – they were obligatory) and various specialist professional courseswhich were to facilitate the personnel “pulling themselves together” in the civil life.<strong>Gan</strong>owicz completed his civil education and – at the same time – he finished a profoundlysecret officers’ course accompanied with parachute training. This undertaking was conducted bymeans of the American funds by <strong>Polish</strong> and French instructors, to the full knowledge and approval ofboth the unrecognised government in exile as well as the highest rank commanding officers of theSecond World War period.Thus, <strong>Gan</strong>owicz received the officer brevet from general Władysław Anders, the last ChiefCommander and General Inspector of the <strong>Polish</strong> Military Forces. It should be said that the sameprocess of the cooperation of several intelligence services in the area of training officers for theemigration armies during the cold war has not been fully researched yet. However, there is much toindicate that it was one of the elements of a comprehensive strategy of NATO in the case of theSoviet invasion described as “stay behind” or “Gladio”.In the next years, <strong>Gan</strong>owicz worked as a teacher in a lower secondary school for <strong>Polish</strong>refugees in Les Ageux in the vicinity of Paris. He was also convinced that the problem of62 After the end of the Second World War, the occupation administration in Germany was faced with the problemof solving the problem of the <strong>Polish</strong> people who refused to come back to the country. One of the measureswhich they reached for was organising the <strong>Polish</strong> guard formations. In Tadeusz Kościuszko Training Centreestablished in 1946 in Kaefertal near Mannheim, 133 guard companies – totally over 40 000 people – weretrained. From April 1947, all the companies were subordinated to the Main Liaison Section which was subjectto the Command of the American Armed Forces in Europe. In 1947, the Americans were willing to abandon theprogramme of maintaining the foreign guard companies and to dissolve all of the existing (including the <strong>Polish</strong>ones) companies, however, the reduction was stopped as a result of the Soviet blockade of Berlin in 1948.Then, on a large scale new companies were formed out of the volunteers coming from behind the Iron Curtainand the existing ones were provided with more arms. Next to the <strong>Polish</strong> companies, numerous German, Czech,Baltic, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, and even one Albanian, companies were established. We do not have at ourdisposal the full data on the number of the members of the <strong>Polish</strong> companies. What we know is that as a resultof a large rotation (in particular in the years 1945-1949), there were tens of thousands of people in their ranks.The retained statistics proves the mass recruitment: at the beginning of 1946, there were approximately 40000 volunteers who served in the guard companies (according to the American estimates). In August 1947,after the first reduction, there were nearly 28 000. In March 1948, their number was decreased to around 11600. At the turn of 1949 and 1950, after the crisis of the <strong>Polish</strong> formations triggered off by mass emigration,some of the <strong>Polish</strong> companies were dissolved. However, in the next years, the situation became stable and thenumbers of the units were again increasing. As part of new recruitment, numerous people of foreignnationalities were recruited into the <strong>Polish</strong> units. At that time, in the territories of Germany and France, therewere 22 <strong>Polish</strong> companies which – in the event of the occurrence of appropriate political conditions – had toplay the role of the core of the future emigrationa armies. Cf. W. J Muszyński, Polskie serce pod mundurem,http://www.onr.czyz.org/artykul-64-t-polskie-serce-pod-obcym-mundurem.html, 14.07.2011.

South <strong>Yemen</strong> attacked North <strong>Yemen</strong>, trying to annex it by force (following the example ofKorea where this was not successful or of Vietnam where, unfortunately, this wassuccessful). The invasion broke down. Coup d’états. The country is far from “the models ofdemocracy”. But it is free. And it has the future. And in this, there is a little credit of mine”.In the later period, <strong>Gan</strong> <strong>Gan</strong>owicz worked as a driver, electrician, translator and journalist; hewas an active member of the organisations of <strong>Polish</strong> veterans; he was also a correspondent of RadioFree Europe, acting under the pseudonym Jerzy Rawicz. He was involved in the support of mujahedsin Afghanistan and after the introduction of martial law in Poland (December 12, 1981), he becameinvolved in the help for the <strong>Polish</strong> “Solidarity” opposition. He wrote the book Kondotierzy. Hereturned to Poland permanently in February 1997. On November 22, 2002, at the age of 70, he diedfrom lung cancer. In 2007 he was posthumously conferred with <strong>Of</strong>ficer Cross 3 of the Order PoloniaRestituta (the second <strong>Polish</strong> civilian order after the Order of White Eagle).Rafał <strong>Gan</strong> <strong>Gan</strong>owicz is an ambiguous figure, arousing in Poland much controversy. Thedocumentary film devoted to this person was broadcast by the public television only after theintervention of the group of the members of parliament. His figure is played in a big “fight for thehistorical memory of the nation” fought by various trends of <strong>Polish</strong> political life. Despite all thevarious doubts, it is difficult to accuse <strong>Gan</strong>owicz of betraying the accepted system of values even ifone does not fully accept this system.83 The Order of Polonia Restituta is the second <strong>Polish</strong> civilian order, after the Order of White Eagle. The order has fiveclasses:: Knight's Cross, <strong>Of</strong>ficer's Cross, Commander's Cross, Commander's Cross with Star, Grand Cross.