Maseno University Journal Volume 1 2012

Maseno University Journal Volume 1 2012

Maseno University Journal Volume 1 2012

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

i<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>VOLUME 1 DECEMBER <strong>2012</strong>Special Issue on Atieno-Odhiambo: Proceedings of the Conference Held at <strong>Maseno</strong><strong>University</strong> on 14-15, July 2011i

MASENO UNIVERSITY JOURNAL<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>Editorial BoardiEditor in Chief:Professor P. Okinda Owuor, Department of Chemistry, <strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>, P.O. Box 333 <strong>Maseno</strong>,Code 40105, Kenya. Email: okindaowuor@maseno.ac.ke.Sub-Editors in Chief:Professor Collins Ouma, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Technology, <strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>,P.O. Box 333 <strong>Maseno</strong>,Code 40105, Kenya. Email: couma@maseno.ac.keProfessor Francis Indoshi, Department of Curriculum and Communication Technology, <strong>Maseno</strong><strong>University</strong>, Private Bag <strong>Maseno</strong>. Email: findoshi@yahoo.comSERIES A: (Humanities & Social Sciences)EditorsProf. Fredrick Wanyama, School of Development and Strategic Studies,<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>, Private Bag <strong>Maseno</strong>.Email: fwanyama@maseno.ac.keProf. George Mark Onyango, School of Environment and Earth Sciences,<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>, Private Bag <strong>Maseno</strong>.Email: georgemarkonyango@maseno.ac.keDr. Susan M. Kilonzo,Dr. Leah Onyango,International Advisory Editorial BoardProf. Ezra Chitando,Department of Religion and Philosophy,<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>, Private Bag <strong>Maseno</strong>.Email: mbusupa@yahoo.comSchool of Environment and Earth Sciences,<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>, Private Bag <strong>Maseno</strong>.Email: lonyango@maseno.ac.keDepartment of Religious Studies, <strong>University</strong> ofZimbamwe, W.C.C. Consultant on the EcumenicalHIV/AIDS Initiative in Africa.Email Chitsa21@yahoo.comProf. Dismas A. Masolo, Humanities, Department of Philosophy, <strong>University</strong> ofLouisville, Louisville, Kentucky.Email Da.masolo@louisville.edui

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>iiDr. Sandya Gihar,Advanced Institute of Management, (Chaudhary CharaSingh <strong>University</strong>, Meerit), NH-35, Delhi-Hapur Bye PassRoad, Ghaziabad, India.Email: drsandhya05@gmail.comProf. Shem O. Wandiga, Department of Chemistry, <strong>University</strong> of Nairobi, P.O.Box 30197 - 00100 GPO, Nairobi Kenya.Email: sowandiga@iconnect.co.keProf. Tim May,Co-Director, Centre for Sustainable Urban and RegionalFutures (SURF), <strong>University</strong> of Salford, Manchester,U.K. Email: T.May@salford.ac.uk;ii

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>iiiMASENO UNIVERSITY JOURNALCopyright ©<strong>2012</strong><strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>Private Bag, <strong>Maseno</strong> 40105Kenya<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is an academic channel for dissemination of scientific, social andtechnological knowledge internationally. To achieve this objective, the journal publishes originalresearch and/or review articles both in the Humanities & Social Sciences, and Natural & AppliedSciences. Such articles should engage current debates in the respective disciplines and clearly show acontribution to the existing knowledge.The submitted articles will be subjected to rigorous peer-review and decisions on their publication willbe made by the editors of the journal, following reviewers’ advice. <strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> does notnecessarily agree with, nor take responsibility for information contained in articles submitted by thecontributors.The journal shall not be reproduced in part or whole without the permission of the Vice Chancellor,<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>.Notes and guides to authors can be obtained from the <strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> website or at the back ofthis issue of the journal every year, but authors are encouraged to read recent issues of the journal.ISSN 2075-7654iii

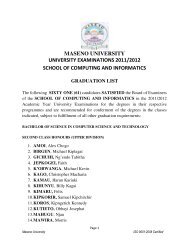

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>vThe Home as a Text: A critical examination of spatio-temporal symbolism in Luo context ...... 146Jack O. Ogembo and Catherine Muhoma ............................................................................... 146The Production of Knowledge in, of, and about Africa: The works of Elisha Stephen Atieno-Odhiambo – Keynote Address ................................................................................... 156Bethwel A. Ogot .................................................................................................................... 156An analysis of the Late Professor Atieno-Odhiambo’s Historical Discourses as a Corpus forLexicography of the African Linguistics ...................................................................... 177Benard Odoyo Okal ............................................................................................................... 177From Round Huts to Square Houses: Spatial Planning in Luo Culture ................................ 186George M. Onyango .............................................................................................................. 186Nationalism in Kenya: Weakening the Ties that Bind ..................................................... 207Peter Wanyande .................................................................................................................... 207v

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>2brought about certain consequences, positive ornegative. It could also mean that one recognizesand pledges that it is his or her role to makesomething happen or prevent it from happening.Thus one could argue that to think about theidea of responsibility is to invoke the notion offree will and freedom of action.The broad idea of responsibility alsoinvolves raising questions about liability, oraccepting failure on behalf of a company orgroup which one has been selected to lead. Inmany cases people dismiss responsibility in thelast case as a form of political maneuvering, buttaking responsibility for a disaster or majorfailure of operation falls within the broadunderstanding of the notion of responsibility. Butwe must probe further to know what if there areany, is the criteria for assuming or assigningresponsibility to someone or an organization.According to John Fischer and Mark Ravizza“someone who is genuinely morally responsiblemust satisfy certain ‘subjective conditions’: hemust see himself as morally responsible in orderto be morally responsible”(Fischer and Ravizza.,1998; Fischer and Ravizza., 2000). In manycases one accepts that there are morallyresponsible for something because they have nochoice. For instance, if an individual is elected tolead and failure occurs during their time inoffice, then people expect the elected official toassume responsibility for the things that havegone wrong. Sometimes this criterion is difficultfor some ordinary individuals, who may fear thatwas such a rule be generalized, acceptingresponsibility could also lead to criminal liability.In many cases, people expect that state leaders orpolitical actors assume responsibility for broadlydefined failures, or unexpected outcomes whichcould not be predicted or which could not beanticipated and when the leaders acted in goodfaith or in carrying out their constitutionalduties. In general, individuals, more than electedofficials, tend to be hesitant, fearing as we havesuggested that they may also be charged withlegal liability.Scholars often link responsibility tomoral virtue. The Greek philosophers used theterms moral virtue to refer to excellences thatwould enable individuals to function well in thepolis (Alasdair, 1984). These excellences includedprudence, temperance, fortitude, justice,2magnificence, magnanimity, patience,friendship, and modesty. During the Romantimes, many of these were seen as traits that astrong individual should have and hence theword virtue emerged as a description. Duringthe Middle Ages, Saint Thomas Aquinas, adisciple of Aristotle not only discussed theexcellences which had been developed by theGreeks and the Romans, but also articulatedwhat he called theological virtues which includedfaith, hope, and charity as well as other virtueslike prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude.It is no surprise that in his appeal forcontemporary society to revive virtues,MacIntyre has singled out his appreciation of thevirtues at the time of Saint Thomas and theearlier perspective by Saint Augustine.I have come to appreciate the distinctionsmade by J. R. Lucas who has argued that theword responsible might just be the best Englishrendition of the phrase Aristotle used phronimos.Lucas says the term today is used to refer to whathe describes as “all-around reasonableness andreliability, not confined to any particular topicand entering into the most other desirablequalities of character”(Lucas, 1993). Today it is aterm that is associated with a number of actionsthat includes listening, responding, and assumingcertain postures and practices that relate to otherpeople. Since an individual or a group respondsto a situation, Lucas and other moralphilosophers have argued that one could assignor accept responsibility or accept blame for thesituation if a number of things are considered.For example, what were the alternatives theindividual had in responding to a situation?Could the individual have done otherwise? Dosethe position of the individual demonstratethoughtfulness of reasonableness.There are several views on when toassign responsibility. Aristotle claimed thatquestions of responsibility are always prior tothat of freedom (Aristotle and Ostwald, 1962).However, when we encounter a situation today,we do not always stop to ask if someone actedfreely. Our assumption in many situations is thatsomeone acted because he or she felt that was theright thing to do and the actor had the freedomto make that decision. In other words, theindividual was not compelled to take the specificaction. People generally think of responsibility

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>3and freedom of action when things go wrong orthings do not go as intended. However if wereflect on the idea of responsibility, it seemsreasonable to suggest that questions aboutresponsible actions and assumption ofresponsibility should be prior to actions becausethose concerns could provide the framework onwhich to reflect on the moral freedom of choiceavailable to the actor.But an Aristotelian approach mightsuggest that responsibility could also bedetermined in light of whether there weremitigating circumstances that could makeobservers think differently about the action forwhich one is claiming or not claimingresponsibility. J.L. Mackie offers anotherperspective through what he calls the “straightrule of responsibility,” which makes an agentresponsible only for intentional actions (Mackie,1977). Mackie has worked out his thoughtscarefully grounds his position in a largerdescription of intentional systems, whichinvolves a context where behavior is explainableand predictable in light of the beliefs, desires,hopes, fears, intentions, perceptions, andexpectations of a group. It is a combination ofthese various things that makes it easy to assignintention and hence responsibility to a particularaction. This does not solve the problem becausewe must still ask whys is that people who are notdirectly responsible for an action can be blamedfor it or charged in court for it.Here is an example I used at thepresentation at the Thabo Mbeki Institute(Bongmba, <strong>2012</strong>). Those who might considerthe Mackie rule could also consider the severityof a proposed action or the failure to carry out acertain action. For example, if I planned to callJames and chat on the phone and forgot to makethe phone call because I was shopping, I mightbe forgiven. However, if I intended to call Jim ata certain time to give him information he neededto take to a meeting and I failed to call him andsomething went wrong at the meeting, I have anobligation to accept responsibility for failing tomake that telephone call. In this way one stillconsiders intentions and purpose even if onedoes not hold some one responsibility in allcases, everything is not so important (Baier,1991; Held, 2001).3Collective ResponsibilityThe idea of collective responsibility islooked at a little differently. We often seedecisions by people to assume collectiveresponsibility when companies acceptresponsibility like British Petroleum has done forthe massive oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.Therefore groups, corporations, and even statesought to accept responsibility and accept blamefor their actions when those actions affect peopleand the environment in a negative way. Outsidequestions that deal with corporate responsibility,collective responsibility is often raised in thecontext of political and civil strife. In the Africancontext the question of collective responsibilityhas been raised but not always addressedadequately in gruesome events like the Genocidein Rwanda and the post election violence inKenya (Cushman and Stjepan G. Mestovic eds,1996). This is also called collective guilt.The idea of collective guilt is rejected bysome scholars. For example Thomas Cushmanand Stjepan G. Mestrovic have rejectedcollective responsibility that has been attributedto Serbian intellectuals and H.D. Lewis hasrejected group responsibility; describing it as “thebarbarous notion of collective or groupresponsibility” which lets individuals get awaywith their responsibility. While Lewis forinstance reminds us of the need to consider theactions of individuals in cases of mass action likepost election violence or in extreme cases likegenocide where specific individuals have acted tofoster and promote negative actions, I think thatto completely do away with collectiveresponsibility would make it difficult for politicalcommunities and the international community todeal with such things like Holocaust, theRwandan Genocide, and apartheid, although weknow that certain individuals played a key role inconceptualizing, planning, and carrying out thesehorrible crimes. They acted not only in their ownname, but in light of the responsibilities whichthey had at the time as leaders of their state oremployees, security officers, and members of thepolice or armed forces that were expected(compelled) to carry out the decisions of theauthorities (Smith, 1998).It is therefore important to rethinkcollective responsibility because African historyhas been marred by violence initiated by the

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>4colonial project and continued in thepostneocolonial state. While violence remainscomplex, African states can no longer explainthe plight of its people by mainly blaming thecolonial project. In other words, the question ofresponsibility for the success or failure of thestate no longer is a foregone conclusion. It isclear to many observers of the African scene thatthe debates of the late 1980s and 1990s includedthe question of responsibility. While one cannotlook at events in Africa in isolation fromdestabilizing global forces such as slavery,colonialism, and neocolonialism, it is alsoevident to some scholars that one can no longerblame colonial abuses alone for the slow progressand the growing poverty and violence on theAfrican continent. Africans and their leadersparticularly are responsible for much of theviolence that is taking place in Africa today. It isthis necessary to think of collective responsibilityin the context of Africa.My intention here is not to claim thatAfrican states have not made any progresstowards economic and social development. Tomake such a claim would ignore much of theprogress that has been recorded even after the socalled movement towards democracy of the late1980s and the early 1990s. The end of thecolonial era was itself a miraculous achievement.The struggle to build nation states in aninternational and later global context wheresome of the new countries were not prepared toface the challenges, started off successfully inmany countries. However, we must admit thatsomething went wrong and any discussion aboutresponsibility is an attempt to sort out who is toblame for the things that have caused a lot ofpain on the continent. It is therefore the case thatif we raise the question of collectiveresponsibility, we do so to ask who should beblamed for the poverty, conflicts, wars and theatrocities that have been caused in the executionof those wars. Africa has seen or lived through itsshare of major crisis such as the Rwandangenocide, the extension of the Rwandan conflictinto Eastern Congo which resulted in the deathof many people, the war in Darfur, the wars inSierra Leon and Liberia. One major event of the20 th Century that we can certainly ask who isresponsible, or extend blame is the HIV andAIDS crisis. The failure by African leaders toaddress the HIV AIDS crisis as soon as it wasknown as a major global epidemic, places theresponsibility for what has happened on theAfrican leaders. The irresponsible rejectionprotective devices like condoms by religiousleaders also implicate the religious leaders andyes, they should accept responsibility for failureon this score.I also think that when violations ofinternational law have occurred as they have inthe Rwandan genocide, the Darfur genocide, andthe wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone, it isimportant to examine the situation, identifythose who are responsible for the crisis and itsexecution, and hold them accountable. Thiswould mean asking an entire government or stateto assume moral responsibility for the things thathave happened. The idea here is that groups quagroups and not individual members can be heldresponsible. If the entire group cannot be heldresponsible their leaders should be heldresponsible. Most companies today often takeresponsibility for their products and conduct oftheir officials.The difficulty with supporting collectiveresponsibility as moral responsibility for somelies in the fact that one could easily see the causalaspect of collective responsibility, but the moralaspects of it may not always be clear as onewould expect. I think we can identify causalresponsibility which can be analyzed because wecan point to a decision that led to some activitythat harmed someone. It is more difficult todetermine that a group, rather than the peoplewho are part of that group share moralresponsibility for an action or a set of actions.The question here for some critics of the notionof collective responsibility is the question ofgroup. Can a collective cause harm in the sameway as an individual can do? Some criticswonder if the idea of group responsibilityreceives attention mainly because individualmembers of a particular group who have causedharm and injury may claim that they have actedin the interest of the group. Some would arguethat what happens in this case is merelydistributing the amoral acts of a few individualsto the group. Critics do not think so.There are those who argue thatemphasizing collective responsibility in the end4

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>5undercuts the sense of individual values thathave been developed over time.Collective responsibility does not undercutindividual values and freedoms; instead it is thedesire to honor those values that that collectiveresponsibility is emphasized as a way ofaddressing the abuse of power when leaders failto act responsibly in their capacity as leaders ofinstitutions or the states. This includes all acts ofthat violate individual and group rights andincludes the planning and execution of wars thatviolate human dignity to the extreme. Theconcept of collective responsibility makes itpossible to examine war crimes, genocide, andother acts of violence on a larger scale, especiallywhen it is committed by one group againstanother group.One important objection that has beenraised is that it is difficult to assign intent to acollective as one would do to an individualperson. Some argue that groups cannot beblameworthy like individuals; therefore assigningcollective responsibility to a group is tantamountto making members of the group guilty byassociation. Some scholars in the twentiethcentury question the viability of the notion ofcollective responsibility because it overturnsindividualism. In his classic work, Economy andSociety, Max Weber rejected the notion ofcollective responsibility because groups do notact with the same intention that individuals do(Weber, 1914). According to this view, Weber,maintained that it is individuals who determineactions and act intentionally and it easierassigning blame on actions of individuals than agroup. H.D. Lewis has argued forcefully thatcollective responsibility is a barbarous thoughtbecause it is the individual alone who has moralresponsibility (Lewis, 1948). The idea here is thatif we assign collective responsibility, we end upcriminalizing individuals who do not bear moralresponsibility but who become culpable onlybecause they belong to a particular group. Againwhat is central here is intentionality and whetherone could and should assign it to a collective asone would assign intentionality to a single actoror a few actors. Therefore scholars who rejectcollective responsibility maintain that it is onlyindividuals who act with intention and not anenter community (Narveson, 2002).5Scholars who support collectiveresponsibility argue that individuals and groupscould be held responsible because both havepsychological responses and as such oftenrespond to suggestions from others to participatein activities that could implicate individuals aswell as members of a group. Deborah Tollefsenhas argued that groups often also respond toevents with emotions of anger, anddisappointment that individual and groups havenot acted in a moral manner (Tollefson, 2006).This is an important point to underscore becauseif we examine recent actions and violence indifferent places in Africa such as the recent postelection violence in Côte d’Ivoire, and the onethat erupted in Kenya, the actors demonstratedmoral outrage against the manipulation of theelections; actions which they thought was wrong.Such actions do give many clues as to whoshould be assigned responsibility. In suchactions, it is possible to see group intentions.Imagine a pattern which goes something likethis. At the end of the elections, each side hopesthat their candidate would be elected. Many ofthem, who expect that outcome, often follow thedetails. But if at the end something happens, theyare bound to examine what has transpired inorder to file a protest. But the problem in postelectionviolence is that many people are oftenpushed, as it were, to act violently. If they all actviolently as a group, it is likely that theleadership incites the group to act that way. Ifthat is the case, it is a good case to assigncollective responsibility to the leaders and thegroup.Some supporters of collectiveresponsibility assume that a group has the samemind (Sosa, 2009). Margaret Gilbert has arguedthat there is something like shared intentions andcan be attributed to a group. This seems to occurin post-election violence. Many times suchaction requires very careful coordination fromthe leaders, or people who stand to gain the mostfrom such group action, but it is possible to get acrowd to think in a similar way, especially theyare taught to see that their opponents want tomake things difficult for them. What we see insuch a situation is the perception by members ofa group that they are under siege, or somethinghas been stolen from them and it is their right toact as a group to recover what has been taken

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>6away from them. They perceive that the onlyway to respond to this is to engage in the struggleas a group. While each individual has a mind ofhis or her own, it is the case that when theyperceive that they have been threatened, theymight also think that it would be to theiradvantage to act as a group. Under suchcircumstances, the group assumes moral agencyin a manner that we could say an individualtakes moral responsibility. Larry May has arguedthat when such a collective approach is taken,what is at work is a “pre-reflective intention”which precedes further deeper consideration ofthe issues by members of a group (May, 1987;May, 2006). The intentions that emerge fromsuch actions certainly reflect group intentions.Since 1994, scholars, Human RightsGroups have discussed the Rwandan Genocidein detail, as well as the extension of the conflictto Eastern Congo. Those familiar with thehistory of the genocide know that colonials andChristian missionaries demonstrated a preferencefor the Tutsi people who were in the minority. Atthe time of independence, the Tutsis occupiedmany of the responsible positions in the countrywhile the Hutu who were the majority ethnicgroup felt they have been discriminated againstand marginalized. Ethnic feelings were soimportant that the government created identitycards which spelled out one’s ethnic group. Inthe post independent era, ethnic violence wouldbreak out several times. Later on politicaldisagreements led to the creation of theRwandan Patriotic Force which began fightingagainst the government in Kigali. Thegovernment of President Habariyamana reachedan agreement with the RPF, but on his returnfrom an important discussion on theimplementation of the peace accords, his planewas shot down and this triggered the ethnicfighting in which the Hutu majority who hadcarried a campaign against the Tutsi set out toeliminate members of the Tutsi group. The deathof the President just hastened the well laid outplan by Hutu leaders to exterminate the Tutsis.In preparation for that, they had compiled a listof Tutsis that would be killed and orderedweapons that would be used in carrying out thekillings. The Hutus also carried out a systematiccampaign on the radio, educating Hutus to killTutsis and Tutsi sympathizers.6In order to further demonstrate how thenature of collective responsibility may work, twoimportant aspects of this Genocide must bementioned. The first case is the fact that for 100days, the international community did not dovery much to stop the killings. Second, theUnited Nations Peace Keeping forces stationedin Kigali were recalled. As soon as they left thecountry, the full killing machine of the Hutuextremist was unleashed and after about 100days, hundreds of thousands of people werekilled in one most gruesome acts of violence ofthe 20 th century. The international communitythen decided there was enough grounds to assignresponsibility; those who perpetrated thismassive killing. The international communityhas meticulously hunted those individuals downand brought before the international Court thatwas set up in Arusha Tanzania. Since thenumber of people implicated in the promotion orabating of the genocide was so large and theArusha courts could not handle all of them,Rwandans set up the Gacaca Courts, atraditional court which held public hearings inthe local communities and worked through therecognition of the crime, and promotions ofreconciliation.Some would argue that there is strongevidence for assigning collective responsibility tosome members of the Hutu community.Members of that community planned the killingsand persuaded their followers to believe the Tutsiwere their enemies who should be eliminated forthe good of the Hutu community. In the process,the leaders who instigated the genocide came upwith appalling ideas such as raping and killing ofTutsi women because killing a woman meantthat she would no longer give birth to Tutsichildren. Even the clergy as we know from theaccount of the genocide were involved. They didnot protect people who had gone to church orchildren who were in boarding school. Theyallowed the killers to come on sacred ground tocarry out their acts of violence.The question here for opponents ofcollective responsibility would be, why do wehave to think of blaming whole communitieswhen we could identify the perpetrators ofwrongful actions and punish them for theircrimes. Some would prefer that rather thanpursue group responsibility, individuals in a

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>7community and bring them to justice because itis not the case that every member of thecommunity often participates in activities thatcause great harm to others. Thos who supportcollective guilt argue that the leaders acted onbehalf of their community.The second thing on collectiveresponsibility that we need to rethink regardingthe Rwandan genocide is whether theinternational community itself had anyresponsibility or could also share in collectiveguilt. If blameworthiness is related to a moralposition and it can be demonstrated thatmembers of international organizations knewwhat could happen if they left Rwanda and wentahead and recommended that the peace keepingforces should be withdrawn from the volatilesituation. Given what we know today, it is alsopossible to demonstrate that the internationalcommunity could have taken another action. Byfailing to act, or by withdrawing the peacekeeping forces, the international community,through the United Nations made it possible forthe genocide to take place. I think it is possibleand we should raise the question of collectiveresponsibility on this account. The documentary,‘Sometimes in April’, dramatizes the crisis in amanner that helps us think of internationalcomplicity by showing the events in Rwanda,then panning back to what the makers of the filmwant to portray as active meetings at the UnitedStates Department to deal with the crises. If thedocumentary is correct, then the team metalmost daily but did not take any concrete actionto stop the killing. Towards the end, a frustratedState department official expressed herdisappointment that they could not do anythingto stop the killings, but one of the militaryleaders, simply said, the United States had nochoice but remain neutral. He added, that it wasRwandans killing Rwandans and in the nearfuture, the US president would apologize to theworld and say that we will never allow such athing to happen again, and that will be the end ofit. This is what happened and it was not only theleader of the United States but other worldleaders did a similar thing.But let us take a look briefly at theinternational community again, especially therole of the United Nations which ordered itspeace keepers out of Rwanda. One could say that7the security situation in the country haddeteriorated so badly that there was nothing theycould do. One could also argue that if theyremained in the country many of them couldhave been killed or caught in a civil war in whichthey could not do anything even to protect theirown lives. Yet is also clear or at least there issome evidence that the United Nations knewthat the situation in Rwanda had degeneratedand that if all foreigners left the country, it wouldsimply make it possible for an embolden Hutuextremist community to carry on what theirleaders had planned, eliminate the Tutsis. Thefact that the leaders of the United Nations knewthis would happen and went ahead and pulledout the peace keeping forces out of Rwandaconstitutes not only a lapse of judgment but aconcrete action with moral implications that callsopens the door for all to assign collective blamehere because the international communitythrough the United Nations failed to remain andprovide an important buffer zone, and let it beknown that the Hutus could not carry on thekillings because the whole world would bewatching.Speaking ten years after the genocide, theformer UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, saidthat he “could and should have done more tostop the genocide in Rwanda”(BBC News,2011). The former UN chief reportedly said “Theinternational community is guilty of sins ofomission.” Why did Annan take this step intrying to come clean? He was the head of the UNpeacekeeping forces. Under his watch, thepeacekeeping forces left Rwanda, and the Hutussystematically eliminated about 800, 000 people.The former UN Chief went on to say: “I believedat the time that I was doing my best.” Onealmost wants to ask the question, how he couldbelieve that he was doing his best when thehistory of ethnic violence in Rwanda was wellknown! He further admitted that “theinternational community failed Rwanda and thatmust leave us always with a sense of bitterregret.” For the sake of argument, one could askwhat the international community could havedone if the Hutu were so bent in eliminating theTutsi. Annan himself says that the UN couldhave provided reinforcements. When he becameSecretary General it dawned on him that therewas more he could have done to rally support for

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>8the mission in Rwanda. What happened inRwanda was more than a lapse of judgment onpart of UN leaders like Kofi Annan. It wasneglect of responsibility that contributed to acatastrophic outcome. It was not only Annanconfessing but the United Nations SecurityCouncil also apologized in April 2000 andaccepted responsibility for failing to prevent orstop the genocide.Some Rwandans blamed the UN forfailing to protect them. The BBC reportmentioned what we learned of the mass aspectsof the killing. About 4000 Tutsis sought shelterclose to Belgian troops thinking that they wouldbe safe because they were within the proximity ofBelgian keeping forces. But they were not givenany protection. The Canadian commander,Lieutenant General Romeo Dallaire, stated atthe same conference where Annan spoke that theinternational community was not ready to helpthe Rwandans. In a statement which reflectswhat one could say were misplaced priorities ofthe international community which had orderedhim and his troops out of Rwanda, he argued: “Istill believe that if an organization decided towipe out the 320 mountain gorillas there wouldbe still more of a reaction by the internationalcommunity to curtail or to stop that than therewould be still today in attempting to protectthousands of human beings being slaughtered inthe same country." This is not an anti animalstatement, but a reflection of the choices wecould make today in the face of mountinghuman crisis.If we go back to the concept of groupmorality on which the idea of groupresponsibility is based, one could raise manyquestions. For example, should the UN systemhave been indicted? Should Kofi Annan himselfhave been made to answer for his lack ofresponsibility? The answer to this questiondepends on a number of things which certainlyrequires that we determine if Annan or hiscolleagues at the UN knew what would happenand if their attitude was intentional. Here theevidence of intentionality might be questioned bysome. However, some would argue that giventhe volatile situation that had been building up inRwanda since independence, it should have beenclear that pulling out the peacekeeping forceswould unleash a rash of killings. The next8question here would be, could the internationalcourt have prosecuted the UN, the SecurityCouncil, or Kofi Annan and the generals on theground? Some would say that could not happeneven if some people wanted such prosecutionsbecause the international community wouldhave been prosecuting itself. Which leaves thequestion, should leaders like Annan have beenheld responsible? Some would argue that hemade the best decision based on the informationhe had at the time. He did not intend to doanything that would lead to the slaughter of over800,000 people. Even if one makes the case thathe still was negligent and has accepted as much,the counter argument would be, to prosecute himwould in effect be prosecuting the UN itself.As one thinks of this the question, it isobvious that nothing happened to the individualswho were charged with protecting the people andpreventing a war. Why would they be heldaccountable? This is where some would say asthe ones who were responsible, it was their dutyto provide the Security Council and the UN thenecessary information to ask for an increase ofpeacekeeping forces rather than leave Rwanda.There was neglect on part of those leaders, butthe UN itself turned around and gave Annan thetop job at the United Nations. Holding himaccountable would have been applying verytough rigorous standards of moral responsibilityto him. Some would say it is precisely because ofthe magnitude of the neglect that such stringentmoral responsibility should have been expected.Therefore UN leaders should have beenprosecuted as the Hutu leaders who wereprosecuted. Since the International communitydefined genocide and set in place conventionsgoverning the declaration of genocide and stepsto be taken when genocide has occurred, onewould have thought that the UN was in a goodposition to know what to do in the case ofRwanda. Although African countries were notmembers of the UN when those conventions andthe International Declaration of Human Rightswere declared, they subscribed to theseconventions, thus granting the UN jurisdictionon such issues in the African context. Thereforeit would have made sense to hold UN officialsaccountable as a matter of fairness.Global conventions recognize and treatpeople as a group and a good example is the

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>9United Nations concerns for indigenous groups.These groups are increasingly being seen not asabstract entities, but people with rights that arearticulated and often violated. In this case aprominent individual was held responsible forthe crimes that were committed. There are casesin which individuals of members of a certaincommunity may also escape being countered aspart of the guilty party. These happen becauseeven when ethnic cleansing or genocide wascarefully planned and executed in Rwanda, allmembers of the political community do not carrythe same responsibility for the crime. For manypeople the notion of collective guilt is acceptableespecially in the case of Rwanda where certainmembers of the Hutu community engineered the1994 genocide (Mamdani, 2001). We do knowthat not all Hutus were responsible and many ofthem went out of their way to protect Tutsis.However, the national scope of the genocide doshow convincingly that group guilt is reasonablewhen a large segment or its leaders plan actionsand order their followers to carry it out, thatcommunity should be held responsible forcollective guilt. Wole Soyinka has called thehunting down and killing of the Tutsis inRwanda a collectivized crime (Soyinka, 1998).However, it would be a mistake to think that thenotion of collective guilt erases or exoneratesindividuals who have played a key role in thoseevents. In seeking justice crimes againsthumanity, charges have been brought againstleaders like Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, ElieNdayambaje, Alphonse Nteziryayo, SylvainNsabimana, and Joseph Kanyabashi, all ofRwanda, have now been convicted of their rolesin the Rwandan genocide.Responsibility, Freedom and the OtherResponsibility has a relationship tofreedom as I indicated at the beginning. The ideahere is that when we claim that someone isresponsible, we mean that the individual as a freemoral agent, answers by his or her own will fortheir thoughts and actions towards other people.In the main, that is the least we can claim aboutindividual or even collective responsibility. Thequestion here is what if an action takes place in acontext where the individual is not free or isconstrained by circumstances to take actions9which he or she would not have taken like in thecase of actions taken under a dictatorial regimelike apartheid South Africa? While we will notpursue that argument here, it is clear that in sucha situation, the notion of collective responsibilitymight overshadow personal responsibilitybecause it can be shown that people acted incertain ways not out of the exercise of theirfreedom but because they were compelled to act.It is clear then that responsibility is related tofreedom, but under some circumstances, one’sresponsibility can be limited by that individual’sfreedom, an idea that is not only intriguing, butraises important moral dilemmas.The work of Emmanuel Levinas hasbrought a different perspective on the idea ofresponsibility. In ‘Otherwise than Being’, Levinasargues that responsibility is not limited to thetype of deficiencies others suggest. The idea ofresponsibility in Levinas outstrips everylimitation one could place on it and thereforeLevinas brings a different perspective toresponsibility by arguing that one is alwaysresponsible to the other and such responsibilityextends beyond the freedom of the subject(Levinas and Levinas., 1981a). The issue here isnot that one does not have a choice to make, butthe view that one is responsible to the other andcannot allow his or her freedom infringe on thoseresponsibilities because one is infinitelyresponsible for the other in the sense in whichLevinas talks about the relationship to the other.In other words, based on an ethics of the facewhich Levinas has articulated, one is alwaysresponsible and answerable to the otherregardless of the conditions under which youractions take place. Levinas describes thatresponsibility as an obsession which he calls “aresponsibility of the ego for what the ego has notwished, that is for the others”(Levinas andLevinas., 1981b).In this relationship Levinas emphasizesthe freedom of the other which calls intoquestion the plans of the subject. In calling intoquestion, the domination of the subject, Levinasinsists that the powers and the demands of theother who is encountered in the face-to-facerelationship surpass those of the subject. It is ameeting that is filled with contradiction becausethe subject who assumes that he or sheunderstands the other does not understand the

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>10other. Thus the subject who encounters the otheris summoned to responsibility even if the subjectsmight want to use his or her freedom differently.This summons to responsibility according toLevinas significantly changes the debate becauseit invites a new understanding of truth whichmust start when the subject realizes that he orshe does not understand the other. Theontological view and understanding which turnsthe other into an object to be grasped, held, andcontrolled emphasizes the freedom of the subjectat the expense of the other. Levinas in verytelling language argues that the use of knowledgeand understanding to present truth as a graspimplies “knowledge would involve thesuppression of the other by the grasp and by thehold, or by the vision that grasps before thegrasp”(Levinas, 1969a). This eliminates thefreedom of the other. However, despite thisontological egoism, Levinas argues that theother’s face preempts such a grasp and praxis ofdomination as the other also grasps the subject.But this is a different grasp because this graspstops the subject from carrying out itsdehumanizing projects; displaces, andoverthrows the subject’s view of truth.The question then is what is truth?Levinas argues that truth from this perspective isto stand in the face of other and have that otherreject your imperial projects of domination. Theother simply does not tell you that she has adifferent view of what you are doing, but actuallymakes a demand on the subject and Levinas callsthat demand an “appeal to me [which] istruth”(Levinas, 1969b). In this transaction, truthis not a comprehension that is worked out indialogue between the other and the subject, but isalready that relationship. In other words, beingin relationship is truth itself. Levinas calls it amodality of relations between the subject and theother (Levinas, 1969c). Robert Manning hasargued that “truth as a modality of thisrelationship means that truth is inseparable fromthe just relationship between people and, thus,from ethics or morality, or justice”(Manning,1993). Levinas himself is insistent that truth isnot control “but rather to encounter the otherwithout allergy, that is in justice”(Levinas,1969d).What we have here is a claim that to bein the presence of the other, and relate to the10other opens one to truth and truth which is anopportunity to be in the presence of the other onthe terms of the other and not on the basis ofone’s propositions and knowledge. It is to openone’s self to the demands of justice before theother. To be open to the demands of justice inthe presence of the other is to be open to acceptresponsibility for the other. This has implicationsfor our understanding of individual and oneshould add collective responsibility in theAfrican context.Africa stands at a significant crossroadsand it is clear to all that Africa needs to moveforward, and to do that, African leaders need toassume responsibility not only as theirconstitutional obligations, but as a matter offreedom, the freedom of the other(s), who arecitizens. In recent years, Nobel EconomistAmartya Sen has argued that development is notmerely building new infrastructure, but creatingthe conditions for members of our politicalcommunities to experience freedom. Thisfreedom is significantly different from the onearticulated by rulers and those who havegoverned the postneocolonial state during thelast half of the century. If we pursuedevelopment as freedom, it will be clear thatchange goes beyond infrastructural changebecause it is an activity that should respond invery definite ways to who were are as people.Such a view of the other and community opensspaces for individuals to define themselves andfind ways of shaping their communities in newand responsible ways. The great accomplishmentof Sen in ‘Development as Freedom’, is hisinsistence that we cannot define or understanddevelopment and change merely as thepossession of wealth (utilitarians), or merely asthe processes we have used to achieve what wehave (libertarians), but development comes whenwe have acted responsibly and nurtured thecapabilities of people which according to Senconstitutes substantive human freedoms whichwould then allow people in a politicalcommunity to focus on important things thatmatter to people.If we look at political practice in Africawe will discover that many of the areas of humanfreedom which Sen discusses are lacking.Freedom in Sen’s work involves politicalfreedom, economic freedom, opportunities for

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>11members of the political community to excel,socio-political transparency, and creating a socialand political climate that is secure. All thesethings could contribute to the experience ofjustice which Sen defines as the creation ofcapabilities. It is not easy to give complete orsettled answers on these questions because onehas to weigh them in light of the politics of theday and the behavior of the markets, butcapabilities is a useful tool because it offersdifferent ways of understanding poverty, and theother disparity that exists in society such as thegender divide. Developing capabilities requiresthe establishment of strong democraticgovernance where political rights exist. “Politicalrights, including freedom of expression anddiscussion, are not only pivotal in inducingsocial responses to economic needs, they are alsocentral to the conceptualization of economicneeds themselves”(Sen, 2000). When Sendiscusses political rights he is not talking of it inabstraction because he has addressed the rightsof women in development. As part of his overallargument, it is not merely providing women withgoods or money, but paying attention to thewellbeing of women. This is done bystrengthening their capabilities and agency.What is very appealing in the work of Sen is theidea that while he champions democratic idealsand the development of human capabilities, he isopen to fresh ideas on these things. He drawsexamples from India to demonstrate how theWest does not have a monopoly on organizing afunctioning political community. We live at atime when pluralism in all respects must providethe resources and ideas that have to work with toachieve our goals and not ground economicsuccess in a democratic society by selfish valuesalone.Sen like Levinas brings together justice,freedom, and responsibility. What we have inSen is an argument which calls the humancommunity to the reality that we have aresponsibility to see “development as anintegrated process of expansion of substantivefreedoms that connect with one another”(Sen,2000). We may not be happy with this viewbecause those of us who have championed neoliberal ideas as necessary perspective oneconomic development, but Sen has brought tothe conversation ideas that are similar to whatwe have seen in Levinas. Levinas has formulatedhis ideas in response to the long ontologicaljourney of the western, and we should add thepostneocolonial leader as subject. Those threeideas point to a new truth which according toLevinas is the face of the other who stands beforethe subject. That face is not an object. We havedeveloped certain characterization of the other:She is a widow, orphan, wife, concubine,prostitute, member of the opposition party,uneducated, gay, lesbian, AIDS victim, etc. Theface, before which we stand, resists thesecategorizations and calls on us to see the humanface that is in front of us. This face itself is aresistance, the on-going anti colonial and antiimperial project that has been ever beenlaunched. It is a face that calls us to our corevalues. It is a face that reminds us of ourcollective responsibility as the path towardsfreedom.Un-concluding WordThis reflection is written in honor of mysenior colleague Professor Elisha StephenAtieno-Odhiambo whose interdisciplinarythinking moved Africanists to ask local questionsin a global context in a different way. One areaof interest that was always imbedded in his workbut never made explicit was the ethical andmoral implications of our knowledge, power,and place in society. One could argue that inaddition to their declared intention of exploring asociology, politics, and risks of knowledge,Odhiambo and his co-author, David Cohen gaveus an opportunity to reflect on responsibility,may be not in the broad sense as I have tried tosketch it, but left imprints there for one to thinkof individual as well as collective responsibilityeven in a narrow sense of the local community inKenya or the outworking of political rivalry onthe National stage in Kenya.In ‘Burying SM’ (Cohen and Atieno-Odhiambo, 1992), one could argue thatOdhiambo and Cohen addressed not only thedrama of an individual family, and that of anethnic group, but the legal responsibility whichmany African elites ought to assume to ensurethat after their departure, the funeral and burialrites would go smoothly and because he or shemade provisions for all involved to respect the11

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>12will of his surviving spouse, and also madeprovisions for the local traditions. However, onewonders if in taking care of the legal aspects ofhis departure could have solved everything,given that his survivors claimed spousal andsocial responsibility in their respective claims andchoices. The very fact that they mapped out thedrama and included the different voices indicatesthat the idea of personal and social responsibilityis complex and calls for constant negotiation. Inthe death of one individual, the society sawmanifested the multiple debates on gender,kinship, succession, and the extent ofjurisprudence over personal marital matters andcultural claims of the extended family. Assigningpraise and blame here is very difficult becausewhat is involved would be the idea that someoneshould accept responsibility for the aftermath ofSM’s death. Cohen and Odhiambo do notengage in that kind of speculation, but the readercould infer these questions from following thecarefully crafted narrative that gives voice toordinary citizens who themselves would like tosee someone accept blame or take responsibility.If ‘Burying SM’ only hints at the idea ofresponsibility, ‘The Risk of Knowledge’ (Cohen andAtieno-Odhiambo, 2004) perhaps opens, all thesame, an undefined window into the question ofresponsibility. One could argue that the idea ofresponsibility even as a moral category is all overthe book beginning with the expensive trip theKenyan President and his entourage undertaketo Washington DC on a rented Concorde jet atthe Kenyan tax payers’ expense. The largeentourage was made up of ministers and civilservants. This was a political miscalculation thatleads to the fact that President George HerbertW. Bush ignored the visiting Kenyan President,Daniel Arap Moi and preferred to pay attentionto the astute Foreign Minister, the HonorableRobert Ouko, thus giving the impression that theForeign Minister had willfully upstaged theKenyan President and humiliated his boss. Thissuspicion was the beginning of Robert Ouko’sdownfall, so much so that when he died, manysuspected that his enemies might have beenresponsible for his death.Odhiambo and Cohen wrote as socialscientist and had no intention of casting blame,or claiming that they knew who was behind thedeath of the Honorable Foreign Minister. Yet intheir critical analysis, one wonders if they alsomake the reader want to ask the question, who isresponsible? They do not answer that question,but I suspect that if they were to step out of theirunique style of narrative which gave voice to thepublic, they might say responsibility lies in thevary story of the postcolonial state in whichmany a political dispute was settled by eventswhich we cannot adequately account for. I donot intend to pursue these questions here, butclose with this suspense to invite furtherreflection on the idea of collective responsibilityas I have explored in this essay that I havewritten to honor the memory of Professor ElishaStephen Atieno-Odhiambo, my colleague andfriend, in the hope that we can reflect on theimportance of collective responsibility in thepostneocolonial states in Africa.ReferencesAlasdair, M. (1984) After Virtue: A Study inMoral Theory. Notre Dame, IN, NotreDame <strong>University</strong> Press.Aristotle and Ostwald, M. (1962) Nicomacheanethics. Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis,.Baier, A. (1991) A Naturalist View o Persons.Presidential Address. Proceedings of theAmerican Philosophical Association 65.BBC News. (2011). BBC accessed June 9, 2011.Bongmba, E., K. . (<strong>2012</strong>) Responsibility andgovernance presented at the ThaboMbeki Institute for Leadership inJohannesburg, South Africa on 11October <strong>2012</strong>, forthcoming in Investingin Thought Leaderships for Africa’sRenewal, edited by Kwandiwe Knodlo,<strong>2012</strong>.Cohen, D.W. and Atieno-Odhiambo, E.S.(1992) Burying SM - The Politics ofKnowledge and the Sociology of Powerin Africa. London: James Currey Ltd.Cohen, D.W. and Atieno-Odhiambo, E.S. (2004) The Risks of Knowledge:Investigations into the Death of the Hon.Minister John Robert Ouko in Kenya,1990. Athens, OH, Ohio <strong>University</strong>Press, and Nairobi, East AfricanEducational Publishers Ltd.12

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>13Cushman, T. and Stjepan G. Mestovic eds.(1996) The Time we knew: WesternResponses to Genocide in Bosnia. NewYork: New York <strong>University</strong> Press.Fischer, J.M. and Ravizza., M. (1998)Responsibility and Control. Cambridge:Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press.Fischer, J.M. and Ravizza., M. (2000) Replies.Philosophy and PhenomenologicalResearch 61, 467-480.Held, V. (2001) Group Responsibility for EthnicConflict. The <strong>Journal</strong> of Ethics 6, 157-178.Kallen, H.M. (1942) Responsibility. Ethics 52,350-376.Levinas, E. (1969a) Totality and Infinity: AnEssay on Exteriority, trans. AlphonsoLingis. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Duquesne<strong>University</strong> Press, 302.Levinas, E. (1969b) Totality and Infinity: AnEssay on Exteriority, trans. AlphonsoLingis. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Duquesne<strong>University</strong> Press, 291.Levinas, E. (1969c) Totality and Infinity: AnEssay on Exteriority, trans. AlphonsoLingis. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Duquesne<strong>University</strong> Press, 210.Levinas, E. (1969d) Totality and Infinity: AnEssay on Exteriority, trans. AlphonsoLingis. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Duquesne<strong>University</strong> Press, 303.Levinas, E. and Levinas, E. (1981a) Otherwisethan Being, or Beyond Essence, Trans.Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh, Pa.:Duquesne <strong>University</strong> Press, 122.Levinas, E. and Levinas, E. (1981b) Otherwisethan Being, or Beyond Essence, Trans.Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh, Pa.:Duquesne <strong>University</strong> Press, 114.Lewis, H.D. (1948) Collective Responsibility.Philosophy and PhenomenologicalResearch 24, 3-18.Lucas, J.R. (1993) Responsibility. Oxford:Clarendon Press, 11.Mackie, J.L. (1977) Ethics: Inventing Right orWrong. Harmondsworth, 208.Mamdani, M. (2001) When Victims becomeKillers: Colonialism, Nativism, and theGenocide in Rwanda. Princeton:Princeton <strong>University</strong> Press.Manning, R.J.S. (1993) Interpreting Otherwisethan Heidegger: Emmanuel Levinas’sEthics as First Philosophy. Pittsburgh:Duquesne <strong>University</strong> Press, 117.May, L. (1987) The Morality of Groups. NotreDame: <strong>University</strong> of Notre Dame Press.May, L. (2006) State Aggression, CollectiveLiability, and Individual Mens Rea.Midwest Studies in Philosophy XXX,309-324.Narveson, J. (2002) Collective Responsibility.<strong>Journal</strong> of Ethics 6, 179-198.Sen, A. (2000) Development as Freedom. NewYork: Anchor books.Smiley, M. (2010) From Moral Agency toCollective Wrongs: Re-thinkingCollective Moral Responsibility. <strong>Journal</strong>of Law and Policy (Special issue oncollective responsibility) 19.Smiley, M. (2011) Collective Responsibility. TheStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,ed. Edward N. Zalta.Smith, P. (1998) Liberalism and AffirmativeObligations. New York: Oxford<strong>University</strong> Press, 222.Sosa, D. (2009) What is it Like to be a Group?Social Philosophy and Policy 26, 212-226.Soyinka, W. (1998) Hearts of Darkness. TheNew York Times Review of Books(October 4, 1998), 11.Tollefson, D. (2006) The Rationality ofCollective Guilt. Midwest Studies inPhilosophy XXX, 222-239.Weber, M. (1914) Economy and Society 1.13

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>14Kenya’s Elections Law dangles the Prospect of Recall even as it Renders itEssentialy UnworkableCarey Francis OnyangoFaculty of Arts and Social Sciences, <strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong>, PO Box 333, <strong>Maseno</strong>, Kenya.E-mail: cfonyango@yahoo.com______________________________________________________________________________Abstract:The Constitution of Kenya granted the right to recall legislators. In stipulatingthe grounds and procedures thereto, The Elections Act 2011 (Republic ofKenya, 2011) only “...dangles the prospect of recall…even as it renders itessentially unworkable”(Johnston, 2009). The grounds for recall are faithful toChapter Six of the Constitution (Republic of Kenya, 2010, 51-54). That thegrounds must be confirmed by the High Court makes the Act evade thecriticism of recall as a political tool for targeting marginal seats (Coleman,2011). However, the signature requirements for a recall petition, conditionsfor the recall election, and the resulting special election create aninsurmountable hurdle. The Act thus contravenes the constitutional provisionof direct exercise of sovereignty.Key words: Kenya, Elections Law, Unworkable______________________________________________________________________________I. THE GROUNDS FOR RECALL1. Grounds; Faithfull to Chapter Six of theConstitutionArticle 104 of Chapter Eight (The Legislature) ofthe new Constitution of Kenya (Republic ofKenya, 2010, p. 69) give the electorate the rightto recall members of Parliament, both from theSenate and the National Assembly. Parliamentwas in the transitional and consequentialprovisions (Ibid., 190) tasked to enact legislationproviding both the grounds and procedure, andthis came in the provisions of Part IV, “Recall ofa Member of Parliament”, of The Elections Act2011 (Republic of Kenya, 2011).Article 75 (“Conduct of State Officers”) ofChapter Six of the Constitution (Leadership andIntegrity) had already hinted (Republic ofKenya, 2010, pp. 52-53) at some grounds thathave been included in the provisions of TheElections Act 2011. Article 75 states that StateOfficers, in this regard Members of Parliament,who contravene the following provisions ofArticles 75, 76, 77, and 78 Constitution shall besubject to disciplinary procedures, includingthose resulting in dismissal or removal fromoffice:(a) Avoidance of conflict of interest betweenpersonal interests and public or officialduties;(b) Avoiding compromising any public ofofficial interest in favour of a personalinterest;(c) Avoiding demeaning the office held;(d) Delivering to the State a gift or donationreceived on a public or official occasionand which is not subject to exemption byan Act or Parliament;(e) Not maintaining a bank account outsideKenya unless under exemption providedunder an Act of Parliament;(f) Not seeking or accepting a personalbenefit or loan in circumstances thatcompromise the integrity of the officer;(g) A full time State Officer not participatingin any other gainful employment;14

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>15(h) Not holding dual citizenship unless onehas been made a citizen of anothercountry by laws of that country withoutthe ability to opt out.The Elections Act 2011(Republic of Kenya, 2011) inits Section 45 (Republic of Kenya, 2011, p. 629)on the other hand specifies two grounds forrecall. First, that a Member of Parliament maybe recalled if found to have violated theprovisions of Chapter Six of the Constitution.Those provisions as specified in Articles 75, 76,77, and 78 of the Constitution are the 8numerated above. Article 73 of the Constitution(Republic of Kenya, 2010, p. 51) has elaboratedthe grounds as follows;(a) State officers are to exercise theirauthority in a manner consistent with thepurposes and objects of the Constitution;(b) State Officers are to demonstrate respectfor the people;(c) They should promote public confidencein the integrity of the office;(d) They are to be elected in free and fairelections;(e) They must exercise objectivity andimpartiality in decision making, and inensuring that decisions are not influencedby nepotism, favouritism, and otherimproper motives of corrupt practices(f) They are to provide service based onhonesty in the execution of public duties;(g) They are to declare any personal interestthat may conflict with public duties; II.They have to demonstrate accountabilityto the public for decisions and actions;(h) They must demonstrate discipline andcommitment in service of the people.The Second ground specified for recall by TheElections Act 2011 (Republic of Kenya, 2011, p.629) is if a Member of Parliament is found tohave mismanaged public resources.2. Due Process Required to Confirm Groundsfor RecallSection 45 of the act, specifies that the recall canonly be initiated if the grounds so specified areconfirmed through a judgement of the HighCourt. In that way, and by being faithful toChapter Six of the Constitution (Republic ofKenya, 2010, pp. 51-54) in providing for thegrounds for recall, the Act has evaded one of thecriticisms of recall, i.e. it can be used as apolitical tool by organised campaigns to targetmarginal seats (Coleman, 2011). With that it isunnecessary to put insurmountable hurdles in theconditions for circulation of the recall petition, inthe recall election, and subsequent specialelection in the manner that the Act then proceedsto do.3. Comparison of Grounds of Recall fromOther JurisdictionsOne needs to take note of the fact that in somerecall jurisdictions, especially in the most USstates, any registered voter can begin a recallcampaign for any reason. This is something theKenyan law has avoided. Often, the reasons inthe US states are political. The 2011 recall effortsin Wisconsin provide a good example forpolitically-motivated recalls (Legislatures, 2011),that the Kenyan Act has gone out of its way toavoid. Out of the 19 that have recall provisions,only the 8 listed in Table 1 below require specificreasons for recall.Again in most of those 19 US states confirmationof whatever grounds for recall by due process isnot even a requirement.II.SOME PRELIMINARYCONDITIONS FOR FILING ANDINITIATING OF RECALLPETITIONSThe Elections Act 2011 (Republic of Kenya, 2011,p. 630) Section 45 (5) is clearly unconstitutionalwhen it provides that a recall petition shall not befiled against a Member of Parliament more thanonce during the term of that member ofParliament. This provision would only makesense in the case of avoidance of double jeopardywhere the High Court has in a previous instanceruled against the confirmation of the very same15

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>16charge. It would not make sense if the member ofParliament has engaged in a differentcontravention of the provisions specified in thegrounds, or if the High Court had confirmed thevery same charge and the recall petition had forsome reason not exhausted its process.The Section 45 (6) of The Elections Act 2011(Republic of Kenya, 2011, p. 630) is also clearlyunconstitutional when it stipulates that someonewho unsuccessfully contested an election underthe Act shall not directly or indirectly be eligibleto initiate a recall petition. This is discriminatoryto persons who have unsuccessfully contestedelections. Article 104 of the Constitution(Republic of Kenya, 2010, p. 69), as shouldindeed be, has endowed the right of recall on theelectorate as such.III. CONDITIONS FOR CIRCULATING ARECALL PETITIONSome of the conditions specified for circulatingthe petition are clearly problematic.1. The Petitioner Must have BeenRegistered as a Voter in the RespectiveElection:Section 46 (1) of The Elections Act 2011(Republic of Kenya, 2011, p. 630) provides that apetition can only be filed by one who isregistered as a voter in the respective jurisdiction.What is however problematic is an additionalrequirement that the petitioner must have been aregistered voter in the election in respect ofwhich the recall is sought. Again, Article 104 ofthe Constitution (Republic of Kenya, 2010, p.69), as should indeed be, has endowed the rightof recall on the electorate as such.2. Signature Requirements:The signature requirements as provided inSection 46(2, 3, and 4) of The Elections Act 2011(Republic of Kenya, 2011, p. 631) are toostringent, and needlessly so. This is because ashas been argued in Section I above, first thegrounds specified by the Act for recall are nonpoliticaland involve the violation of Chapter Sixof the Constitution or mismanagement of publicresources. Secondly the violations of the groundshave to be confirmed by a judgement renderedby the High Court.The Act states that the petition must beaccompanied by the signatures of voters in therespective jurisdiction making at least 30% of itsregistered voters. Further to that, the 30% figuremust have a spread of at least 15% of registeredvoters in at least half of the number of wards ineither the respective county (in the case of aSenate seat) or the respective constituency (in thecase of a National Assembly seat). Additionally,the 30 % figure must have a spread in terms ofrepresenting “the diversity of people in thecounty or constituency as may be the case”.These signature requirements are extremelydemanding. The 30% sum of registered voters ina jurisdiction is already demanding enough evenbefore it is saddled with the two additionalrequirements for ward and diversity spread. Thesituation is even worsened by the requirementthat the petitioner has to collect and submit thesignatures to the Independent Electoral andBoundaries Commission within 30 days.Perhaps a picture of how demanding thoserequirements are can be gleaned fromcomparisons with provisions from otherjurisdictions.(a). British Columbia, Canada: The signaturerequirements for recall of a member of theLegislative Assembly are very demanding. Thepetitioner has 60 days to collect signatures frommore than 40 per cent of the voters who wereregistered to vote in the Member’s electoraldistrict in the last election. However, unlike inthere are no set grounds with the petitioner onlyrequired to provide a statement of why thelegislator should be recalled. One maynevertheless have to agree that the politicalevents that led to the adoption of the recall in theCanadian Province resulted in “a law thatdangles the prospect of recall …even as it renders[it] essentially unworkable” (Johnston, 2009),and the same could be said of Kenya.16

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>17(a). Ecuador: The request for recall must bebacked by a number accounting for only no lessthan 10% of the persons registered in thecorresponding voter registration list. In the caseof the President of the Republic, backing by anumber accounting for no less than 15% of thepersons registered in the electoral registration list(Ecuador, 2011). There are no otherrequirements.(b). Federated States of Micronesia, Chuuk,Pohnpei, and Yap: Article IX, Section 5, of theConstitution(Federated States of Micronesia,2011a) provides that; (a) a petition for recall ofthe Governor or Lieutenant Governor may beinitiated by a majority of all mayors in the Stateof Chuuk, or by registered voters equal innumber to at least 15 % of those who voted inthe last general election for Governor andLieutenant Governor;(b) a petition for recall of a Senator or aRepresentative may be initiated by a majority ofall mayors in the applicable Representativedistrict or Senatorial Region, or by registeredvoters from such district or region equal innumber to at least 20% of those who voted in thelast general election in such district or region.(c). Federated States of Micronesia, Kosrae:Article VII, Section 1, of the Constitution(Federated States of Micronesia, 2011b) providesthat the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, ajustice of the State Court, or a Senator may beremoved from office by recall initiated by apetition, and be signed by at least 25% of thepersons qualified to vote for the office occupiedby the official, except that recall of a justice ofthe State Court requires the same number ofsignatures as a statewide elective office.(d) Germany: The constitutions of some statesgive the electorate the right to recall entirelegislatures.(i) In Baden-Wuerttemberg that can be initiatedthrough a petition signed by 200, 000.00registered voters, as per part II Article 43 of theconstitution (Baden–Wuerttemberg., 1953). Thepopulation of that state is in the range of around10, 000, 000.00 (European Social Fund, nd) sothat the number of signatures required makes upjust about 2.5% of the population.(ii) Bavaria: In Bavaria, the constitution in TitleII, Article 18 (2) (Bayern, 1946), provides for arecall of the entire legislature in a referendum ifpetitioned by 1, 000, 000.00 registered voters.The population of Bavaria now stands atapproximately 12, 443,893 (Government of theState of Bavaria, 2011). The required number ofsignatures is thus below 10% of the totalpopulation. About 84.5% of the population isabove 15 years of age, meaning that most ofthem are of voting age hence increasingpossibilities for the availability of potentialpetitioners.(iii) Berlin: According to the constitution of thecity-state of Berlin, Article 63, a recall of thecomplete legislature can be initiated by 20% ofthe registered electors (International Institute forDemocracy and Electoral Assistance, 2008, p.116). During a political crisis in January 1981 theChristian Democratic opposition started acitizens’ initiative to recall the legislature. Withina few days, 300,000 signatures – more than thequorum required – had been collected. In March,the parliament decided to call an early election inMay 1981, without waiting for the referendumvote. Since the goal of the initiative had beenreached the petition was withdrawn.(iii) Brandenburg: Article 76(1) of theconstitution (State of Brandenburg, 1992)provides for the recall of the entire legislaturethrough an initiative that has to be signed by atleast 150, 000.00 registered voters. Thepopulation of Brandenburg is about 2, 500,000.00 (Government of the State ofBrandenburg, circa 2004, p. 3), and thus therequired signatories is just above 5% of thepopulation.(iv) Bremen: Article 70 of the constitution(FreeHanse City of Bremen 1947) provides for aninitiation of recall of the entire legislaturethrough a petition signed by at one fifth ofregistered voters, i.e. about 20%.17

<strong>Maseno</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>Volume</strong> 1 <strong>2012</strong>18(e). Kiribati: This presents another case of aquite high figure of signatures required for filinga recall petition. Chapter V, Section 59 (1) of theConstitution (Republic of Kiribati, 2007)provides that subject to the provisions ofsubsections (6) and (7) of the section, if theSpeaker receives a petition calling for theremoval of an elected member of the Maneaba niMaungatabu (legislature) signed by a majority ofthe persons who were registered as electors, atthe time of the last election of that member, inthe electoral district from which that memberwas last elected, he shall send the petitionforthwith to the Electoral Commission.(f). Liechtenstein: Article 48 of the Constitutionprovides that the entire legislature may berecalled if up to 1,500 Liechtenstein citizenseligible to vote or four municipalities, by meansof resolutions of their municipal assemblies,demand a popular vote on the dissolution(Liechtenstein, 2009). The population ofLiechtenstein was in July 2011 estimated atabout 35, 236 (Index Mundi, 2011). Thus thesum of 1500 eligible voters required to sign apetition to recall the legislature is less than 5% ofthe entire population at least. Those of votingage were estimated to make up about 84% of thepopulation, i.e. a figure of about 29, 571. So thesum of 1500 eligible voters is just about 5% of thepopulation of eligible voters. Of course one musttake into account the fact that it would not be toobig a problem to organize an election for 35, 000,so that the recall of the entire legislatures shouldnot be that much of a big deal.(g). Nigeria: This appears to be on the sameprohibitive side as in the Kenyan case. Articles69 and 110 of the Constitution of the FederalRepublic of Nigeria, 1999(Law, 2009) provide thatrecall petitions for either members of theNational Assembly of the Senate has to be signedby more than one-half of the persons registeredto vote in that member's constituency allegingtheir loss of confidence in that member.(h). Palau: Article IX, Section 17 of theConstitution(Constitution of the Republic ofPalau, 1981) provides that the people may recalla member of the Olbiil Era Kelulau (legislature)18if initiated by a petition signed by not less than25% of the number of persons who voted in themost recent election for that member of theOlbiil Era Kelulau.(i). The US: In the 19 states that have recallprovisions, as listed in Table 2 below, thesignature requirements are also more or less as inthe other jurisdictions based on a formula,generally, a percentage of the vote in the lastelection for the office in question, although somestates base the formula on the number of eligiblevoters or other variants. The signaturerequirements, as one can see from Table 2, are:25% in nine states; 25% for state wide offices and35% for other offices in Washington; one-third(1/3) in Louisiana; and 40 % in Kansas.California's requirements are 12% for state wideoffices and 20 % for state senators and appellatejudges(Constitution of the State of California,1879). Georgia requires 15% for state wideoffices, and 30% for all others. Idaho requires20% for all offices. Montana has the lowestnumber of required signatures, i.e. 10% for statewide officials and 15% for state district officessuch as legislative districts.A look at the percentages in Table 2 indicatesthat the average percentage of signaturesrequired for state wide officials (governors, statelegislators, and other state officials) in the 19states, is about 22.7%. One arrives at thataverage percentage by adding the percentagesprovided for each state in regard to state wideoffices and then dividing it by 19. In the case ofCalifornia one has to get the average percentagebetween the 12% for some state wide offices andthe 20% for other state wide offices like senatorsand appellate judges. In Louisiana one has to getthe average percentage between the 33.3% forjurisdictions with over 1000 voters and the 40%for those with over 1000 voters.Only in the cases of California and Illinois arethere additional requirements relating to spreadof the percentage of signatures needed, and theseare hardly as prohibitive as in the Kenyan case.In California the 12% needed for state wideoffices (other than senators and appellate andtrial judges, and members of the Board ofEqualization) has only to include 1% from each