(OPPE) Using Automatically Captured Electronic Anesthesia Data

(OPPE) Using Automatically Captured Electronic Anesthesia Data

(OPPE) Using Automatically Captured Electronic Anesthesia Data

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

78<br />

The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety<br />

or a simulated patient scenario modifies behavior. It also has<br />

minimal costs to install and maintain and is unbiased in its measurement<br />

of clinical performance. It is not intended to provide a<br />

complete system for measuring competence but rather to serve<br />

as a first-round warning mechanism and metric scoring tool to<br />

identify problems and potential performance noncompliance issues.<br />

Numerous problems can arise in the process of delivering<br />

anesthesia care (or any clinical practice), such as failure to perform<br />

basic patient monitoring in a fashion that ensures the safety<br />

of the patient. Continuous and transparent systems such as ours<br />

enable physicians to self-assess their performance and make adjustments<br />

to correct issues before engaging in the credentialing<br />

process.<br />

Although the process of credentialing professionals in health<br />

care is not new, 16–18 there are few in-depth analyses of physician<br />

performance evaluation, and most are focused on overtly technical<br />

skills; some address generalized professional skill sets. Generalizable<br />

skills and specialized knowledge are both important to<br />

clinical care and should be included in any competence metric. 19<br />

Surgery and endoscopy practices place a high value on quantifying<br />

technical skills. 20–22 In anesthesia, it has been suggested that<br />

technical clinical performance can also be readily evaluated by<br />

simulation 23 or control chart methodology. 24<br />

The development of our credentialing system reflects similar<br />

work reported by others. 25 Schartel and Metro suggest that evaluation<br />

should take place close to the time of the clinical encounter<br />

and should be intended to not only correct mistakes but<br />

also continuously improve performance. 26 Fried and Feldman<br />

state that technical performance measurements should be objective<br />

and practical for a clinical specialty. 27 Hill argues for standardized<br />

credentialing, 28 but we believe that it is nearly<br />

impossible to standardize the clinical behavior of an entire profession.<br />

Credentialing parameters should be specific enough to<br />

enhance patient care by resolving issues within a specialty. 29 In<br />

any case, because of uneven adoption of technology—for example,<br />

clinical data coding is not universal—it would be unrealistic<br />

to set standards beyond the capacity of smaller hospitals. 30<br />

The purpose of credentialing is to improve patient care, and thus<br />

should be dictated by each specialty’s organization and the health<br />

care institutions themselves.<br />

It should be noted that the purpose of our work was to design<br />

a credentialing process suitable to our own department, with its<br />

particular work flow and clinical practice, rather than for all<br />

medical specialties or even anesthesia as a whole. These metrics<br />

are intended to apply to anesthesiologists in clinical practice in<br />

the OR—who constitute the vast majority of hospital-based<br />

practicing anesthesiologists—and will not apply to all anesthesiologists,<br />

such as pain and ICU physicians. However, we believe<br />

that our results as presented have broad applicability to fields in<br />

which significant structured clinical and compliance documentation<br />

are important components of clinical practice.<br />

Other fields of medicine, particularly ICUs, have used a similar<br />

methodology to enact a system of defining and measuring<br />

metrics of patient care and physician performance. For example,<br />

Wahl et al., without incurring the need for additional personnel,<br />

used a computerized system to collect data on ICU core<br />

mea sures—glucose management, head of bed angle, prophylaxis,<br />

and ventilator weaning. 31<br />

MIDCOURSE CORRECTIONS AND NEXT STEPS<br />

We are in the process of developing additional metrics, coupled<br />

with a determination of which metrics to add or remove on<br />

the basis of their performance over time. Potential future metrics<br />

may include those based on the total case duration or “time-inflight,”<br />

as opposed to what we have initially used, that is; casebased<br />

metrics (items that occur only once per case). This<br />

adjustment reflects the fact that some of our clinicians (for example,<br />

members of our cardiac group) perform a small number<br />

of long cases, as opposed to the majority of clinicians, who administer<br />

a moderate number of relatively short-duration anesthetics.<br />

The long-term goal of the credentialing system is to<br />

develop a comprehensive group of metrics that best represents<br />

the scope of clinical OR anesthesiology.<br />

February 2012 Volume 38 Number 2<br />

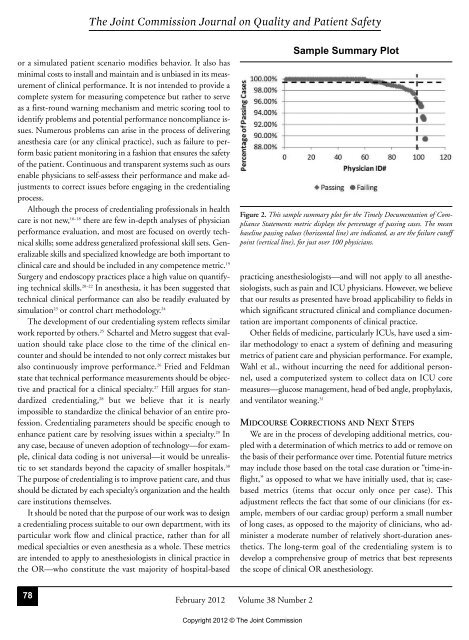

Sample Summary Plot<br />

Figure 2. This sample summary plot for the Timely Documentation of Compliance<br />

Statements metric displays the percentage of passing cases. The mean<br />

baseline passing values (horizontal line) are indicated, as are the failure cutoff<br />

point (vertical line), for just over 100 physicians.<br />

Copyright 2012 © The Joint Commission