College of Veterinary Medicine Research Brochure

College of Veterinary Medicine Research Brochure

College of Veterinary Medicine Research Brochure

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

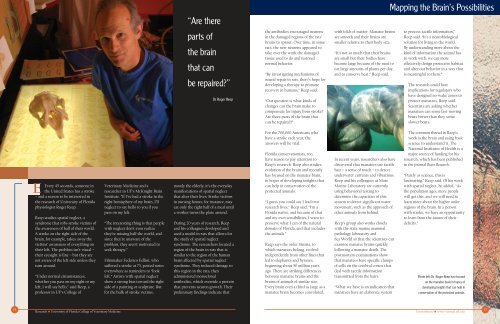

“Are thereparts <strong>of</strong>the brainthat canbe repaired?”Dr. Roger Reepthe antibodies encouraged neuronsin the damaged regions <strong>of</strong> the rats’brains to sprout. Over time, in somerats, the new neurons appeared totake over the work the damagedtissue used to do and restorednormal behavior.“By investigating mechanisms <strong>of</strong>neural repair in rats, there’s hope fordeveloping a therapy to promoterecovery in humans,” Reep said.“Our question is what kinds <strong>of</strong>changes can the brain make tocompensate for injury from stroke?Are there parts <strong>of</strong> the brain thatcan be repaired?”with folds <strong>of</strong> matter. Manatee brainsare smooth and their brains aresmaller relative to their body size.“It’s not so much that their brainsare small but their bodies havebecome large because <strong>of</strong> the need toeat large amounts <strong>of</strong> plants per day,and to conserve heat,” Reep said.Mapping the Brain's Possibilitiesto process tactile information,”Reep said. “It’s a neurobiologicalsolution for living in the world.By understanding more about thekind <strong>of</strong> information the animal hasto work with, we can moreeffectively design protective habitatand alter our behavior in a way thatis meaningful to them.”The research could haveimplications for regulators whohave designed no-wake zones toprotect manatees, Reep said.Scientists are asking whethermanatees can sense fast-movingboats better than they senseslower boats.EEvery 45 seconds, someone inthe United States has a stroke– and a reason to be interested inthe research <strong>of</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Floridaphysiologist Roger Reep.Reep studies spatial neglect, asyndrome that robs stroke victims <strong>of</strong>the awareness <strong>of</strong> half <strong>of</strong> their world.A stroke on the right side <strong>of</strong> thebrain, for example, takes away thevictims’ awareness <strong>of</strong> everything ontheir left. The problem isn’t visual –their eyesight is fine – but they arenot aware <strong>of</strong> the left side unless theyturn around.“Under normal circumstances,whether you pass on my right or myleft, I will say hello,” said Reep, apr<strong>of</strong>essor in UF’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> and aresearcher in UF’s McKnight BrainInstitute. “If I’ve had a stroke in theright hemisphere <strong>of</strong> my brain, I’llneglect to say hello to you if youpass on my left.“The interesting thing is that peoplewith neglect don’t even realizethey’re missing half the world, andsince they’re unaware <strong>of</strong> theproblem, they aren’t motivated toseek therapy.”Filmmaker Federico Fellini, whosuffered a stroke at 73, posted noteseverywhere as reminders to “lookleft.” Artists with spatial neglectshow a strong bias toward the rightside <strong>of</strong> a painting or sculpture. Butfor the bulk <strong>of</strong> stroke victims,mostly the elderly, it’s the everydaymanifestations <strong>of</strong> spatial neglectthat alter their lives: Stroke victimsin nursing homes, for instance, mayeat only the right half <strong>of</strong> a meal untila worker turns the plate around.During 20 years <strong>of</strong> research, Reepand his colleagues developed andused a model in rats that allows forthe study <strong>of</strong> spatial neglectsyndrome. The researchers located aregion <strong>of</strong> the brain in rats that issimilar to the region <strong>of</strong> the humanbrain affected by spatial neglectsyndrome. They induced damage tothis region in the rats, thenadministered monoclonalantibodies, which override a proteinthat prevents neuron growth. Theirpreliminary findings indicate thatFor the 700,000 Americans whohave a stroke each year, theanswers will be vital.Florida conservationists, too,have reason to pay attention toReep’s research. Reep also studiesevolution <strong>of</strong> the brain and recentlyhas focused on the manatee brain,in hopes <strong>of</strong> developing insights thatcan help in conservation <strong>of</strong> theprotected animals.“I guess you could say I lead tworesearch lives,” Reep said. “I’m aFlorida native, and because <strong>of</strong> thatand my own sensibilities, I want topreserve what I can <strong>of</strong> the naturaldomain <strong>of</strong> Florida, and that includesthe animals.”Reep says the order Sirenia, towhich manatees belong, evolvedindependently from other lines thatled to elephants and hyraxes,beginning about 50 million yearsago. There are striking differencesbetween manatee brains and thebrains <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>of</strong> similar size.Every brain even a third as large as amanatee brain becomes convoluted,In recent years, researchers also havediscovered that manatees use tactilehair – a sense <strong>of</strong> touch – to detectunderwater currents and vibrations.Reep and his colleagues at MoteMarine Laboratory are currentlyusing behavioral testing todetermine the capacities <strong>of</strong> thissystem to detect significant watermovement, such as the approach <strong>of</strong>other animals from behind.Reep’s group also works closelywith the state marine mammalpathology laboratory andSea World so that the scientists canexamine manatee brains quicklyfollowing a manatee death. Thepostmortem examinations showthat manatees have specific clumps<strong>of</strong> cells on the cerebral cortex thatdeal with tactile informationtransmitted from the hairs.“What we have is an indication thatmanatees have an elaborate systemThe common thread in Reep’swork is the brain and using basicscience to understand it. TheNational Institutes <strong>of</strong> Health is amajor source <strong>of</strong> funding for hisresearch, which has been publishedin the journal Brain <strong>Research</strong>.“Purely as science, this isfascinating,” Reep said. Of his workwith spatial neglect, he added, “Asthe population ages, more peoplewill get this, and we will need tolearn more about the higher orderregions <strong>of</strong> the brain. In a personwith stroke, we have an opportunityto learn from the nature <strong>of</strong> theirdeficits.”Photo left: Dr. Roger Reep has focusedon the manatee brain in hopes <strong>of</strong>developing insights that can help inconservation <strong>of</strong> the protected animals.34<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Environment • www.vetmed.ufl.edu35