College of Veterinary Medicine Research Brochure

College of Veterinary Medicine Research Brochure

College of Veterinary Medicine Research Brochure

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

University <strong>of</strong> Florida<strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong><strong>Research</strong>Advancing Human, Animal and Environmental Health

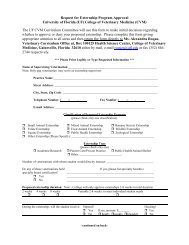

University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> Introduction<strong>Research</strong>University <strong>of</strong> Florida<strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>• Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1—2• <strong>Research</strong> Highlights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3• Keeping Tick-borne Diseases at Bay . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4• Racing to Determine Causes <strong>of</strong> Greyhound Deaths . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6• Helping Frail Foals Survive . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8• Seeking Solutions to Cat Overpopulation Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10• Troubleshooting West Nile Virus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12• Foamy Viruses Show Gene Therapy Potential . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14• Charting New Territory With Immunodeficiency Virus <strong>Research</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16• Changing Standards <strong>of</strong> Care While Improving Sight . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18• Advancing Animal Reproductive Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20• Studying the Cough Mechanism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22• Focusing on Breathing Awareness and Respiratory Disease . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24• Evaluating Treatments for Osteoporosis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26• Mycoplasmas Play Key Role in Disease <strong>of</strong> Humans, Animals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28• Advancing Health <strong>of</strong> Wildlife, Endangered Species . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30• Mapping the Brain’s Possibilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32• Assessing Risks to Animal, Human and Environmental Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .34• Giving Opportunities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .36• Contact Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Inside Back Cover• Infectious Diseases • Clinical • Physiology • Environment • GeneralWWhether developing newways to restore sight andsense, pinpointing levels <strong>of</strong> toxicityin the environment, or investigatingmicroscopic organisms and virusesto protect against disease,researchers at the University <strong>of</strong>Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong><strong>Medicine</strong> are in the forefront <strong>of</strong>advancing animal, human andenvironmental health.Improving quality <strong>of</strong> life foryou, your pets, food animalsand the world’s endangered speciesis our primary goal, and ourobjectives for doing this unfold inmultifaceted ways every day at theUF veterinary college.We hope this document willenhance your awareness <strong>of</strong> whatwe do here at the college and howour multiple approaches to diseasediagnosis and prevention cometogether to make up the whole <strong>of</strong>who we are as an institution andhow we serve the public. Basicbiomedical research aimed atimproving human health, clinicalresearch to improve domestic animalhealth and productivity, andconservation medicine and biologyto improve the health and wellbeing<strong>of</strong> wildlife and ourenvironment are all part <strong>of</strong> ouroverall college research program.In this brochure, we’ve put faces tosome <strong>of</strong> the individuals who makeup these programs, and the storiesyou will read here <strong>of</strong>fer uniqueinsights into not only who’s doingwhat, and why, but also food forthought as to why research makesa difference in our everyday lives.Some <strong>of</strong> our individualresearchers and theirprograms are better knownthan others. Many readersmay know already that avaccine against FelineImmunodeficiency Virus(Feline AIDS) wasdeveloped and patentedby a UF researcher whosework into relationshipsbetween FIV and humanAIDS is ongoing. Othersfamiliar with the college’shistory may recall that one<strong>of</strong> the cornerstones <strong>of</strong> ourresearch program was theinfectious disease groupfocusing on devastatingtick-borne diseases suchas heartwater in livestock.This group’s role inkeeping such diseases atbay in sub-Saharan Africaand preventing them fromtaking root in the U.S. hasreceived internationalrecognition throughcontinued funding fromagencies such as the U.S.Agency for InternationalDevelopment. As a result<strong>of</strong> our team’s dedication,a vaccine againstheartwater is believed tobe close at hand.Introduction, continued on page 2Dr. Joseph A. DiPietro, dean, and Dr. Charles H. Courtney,associate dean for research and graduate studies•www.vetmed.ufl.edu3

<strong>Research</strong> HighlightsIntroduction, continued from page 1The preferred animal model for thestudy <strong>of</strong> osteoporosis in womenwas developed by one <strong>of</strong> our facultymembers in the mid 1980s. Thatsame individual has helped evaluateseveral osteoporosis treatments nowon the market. Mice that were part<strong>of</strong> his related studies involving boneloss and its relationship toweightlessness have flown on theSpace Shuttle.More recently, UF veterinaryresearchers made headlines whenthey reported in conjunction withthe Centers for Disease Controlthat equine influenza virus hadjumped species into dogs and wasthe likely cause <strong>of</strong> several racinggreyhound deaths in Jacksonville.Mysterious greyhound deathscontinue in Florida and elsewherefrom respiratory illness,and so does our investigators’research into the cause.Another <strong>of</strong> our researchers is wellknown locally and internationallyfor her advocacy <strong>of</strong> homeless catsand her studies <strong>of</strong> how to improvecat population control.When West Nile virus begangrabbing media attention a fewyears ago, another <strong>of</strong> our researcherssoon became the point person formonitoring the incidence <strong>of</strong>outbreaks affecting horses at our<strong>Veterinary</strong> Medical Center andelsewhere in Florida. With fundingfrom state and federal sources, shehas helped to build a database thatwill help both horse owners andveterinary pr<strong>of</strong>essionals betterunderstand the potential forinfection as well as how to bettertrack West Nile disease spread.In spite <strong>of</strong> all the publicacknowledgments our researchershave received, much work continueswithout headlines or fanfare. In thiscollection <strong>of</strong> stories, a meaningfulcross-section <strong>of</strong> research takingplace here at the college, wecelebrate all <strong>of</strong> these individualsand their commitment to keepinganimals, humans and theenvironment healthy. We hopeyou will as well.Best Regards,Joseph A. DiPietro, D.V.M. M.S.Dean, UF <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>Charles H. Courtney, D.V.M. Ph.D.Associate Dean for <strong>Research</strong> andGraduate StudiesTThe <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong><strong>Medicine</strong> at the University<strong>of</strong> Florida, the state’s only veterinarycollege, <strong>of</strong>fers comprehensive serviceto the public through a fourfoldmission: teaching, research,extension, and patient care.Following graduation <strong>of</strong> its firstclass in 1980, the college has builton the university’s reputation forexcellence and is consistentlyranked in the top 10 <strong>of</strong> all U.S.veterinary colleges by U.S. Newsand World Report.The college is unique in that itis administered jointly by UF’sInstitute <strong>of</strong> Food and AgriculturalSciences and the Health ScienceCenter, with the Dean <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> answering toboth the Vice President forAgriculture and Natural Resourcesand the Vice President for HealthAffairs. Over half <strong>of</strong> college facultyhold both IFAS and HealthScience Center facultyappointments. Organizationally,the college is divided into fouracademic departments.The department <strong>of</strong> large animalclinical sciences is responsible forteaching, clinical service andresearch involving diseases <strong>of</strong>livestock, poultry and fish. Majorprograms include animalreproduction, food animalproduction medicine, equine colicand equine performance medicine.The department <strong>of</strong> pathobiologyis responsible for teaching, clinicalservice and research involvingpathology, molecular biology,microbiology and parasitology<strong>of</strong> animal diseases. Major programsinclude tick-borne diseases,EPM in horses, the AIDS viruses<strong>of</strong> animals and mycoplasmaldiseases. The department alsohosts the college’s comparativeclinical immunology program.The department <strong>of</strong> physiologicalsciences is responsible for teaching,clinical service and researchinvolving basic physiology andtoxicology. Major programs includeenvironmental toxicology, forensictoxicology, the neurosciences, andrespiratory and cardiac physiology.The department <strong>of</strong> small animalclinical sciences is primarilyresponsible for teaching, clinicalservice, and research involvingdiseases <strong>of</strong> pets and zoo animals,but some work is done withlivestock, primarily in the field<strong>of</strong> ophthalmology.In addition to the above fourdepartments, the college also is hostto the Center for Environmental andHuman Toxicology. Included withinthis center are the analytical coretoxicology laboratory, the aquatictoxicology facility and theUniversity <strong>of</strong> Florida RacingLaboratory. The racing laboratory,one <strong>of</strong> only five such internationallycertified laboratories in the UnitedStates, is responsible for conductingdrug screens on all horses andgreyhounds raced at tracksthroughout Florida.The college also hosts theuniversity’s marine mammalprogram jointly with theWhitney Laboratory. Thisinterdisciplinary programsupports research and training inthe care <strong>of</strong> marine mammals withemphasis on manatees.In the 10 years from 1994 to 2004, thedollar amount <strong>of</strong> grants and contractsawarded annually to UF <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong><strong>Medicine</strong> faculty nearly doubled, from$5,221,642 in 1994 to $9,616,498 in2004 despite an overall decline in statesupportedfaculty numbers.Most <strong>of</strong> the increase was a result <strong>of</strong> a 2.5-foldincrease in federal funding, a 3-fold increasein corporate funding and a 3.5-fold increase infunding from charitable foundations, whereasresearch grant funding by the state <strong>of</strong> Floridadeclined to 80 percent <strong>of</strong> 1994 levels.4<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••www.vetmed.ufl.edu5

Keeping Tick-borne Diseases at BayKKeeping the ticks that carrydeadly heartwater diseasefrom jumping U.S. borders andinfecting livestock and wildlifemight seem like an impossible task,the kind that would take a giantfence around the country.But a research team at theUniversity <strong>of</strong> Florida’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> thinks a goodvaccine to prevent heartwaterwould be better – and more effective– than any fence.And after two decades <strong>of</strong> workingwith heartwater disease, the team ison the verge <strong>of</strong> marketing aconventional vaccine even as itworks to develop an even bettervaccine with genetic engineering.Heartwater is spread to livestockand wildlife by the bont tick, anative <strong>of</strong> Africa. The transoceanictropical bont tick has shown up inthe Caribbean, lurking just <strong>of</strong>fFlorida’s shores and making itsarrival in the United States possibleif not likely.The UF Heartwater <strong>Research</strong>Project, led by pathobiologyPr<strong>of</strong>essor Michael Burridge, hasbeen in a 20-year race against timeto understand the disease, developbetter methods to diagnose it,control the ticks that carry it andinvent a vaccine to protect against itif – or when – it arrives.Heartwater can kill up to 90 percent<strong>of</strong> the animals it infects, decimatingan entire herd. The disease damagesthe lining <strong>of</strong> blood vessels, allowingfluid to accumulate in the lungs andbody cavities, causing an agonizingdeath for the infected animal. Thetropical bont tick also is associatedwith acute dermatophilosis, adisease that causes the skin <strong>of</strong> cattleliterally to peel <strong>of</strong>f. Burridge said itis impossible to underestimate thethreat to U.S. wildlife and livestockfrom the tropical bont tick.“Heartwater is a potentialbioterrorism or agriterrorism agent,”Burridge said. “It’s a disease wedefinitely need to keep out <strong>of</strong> theUnited States.”Burridge, a parasitologist andepidemiologist, points out thatmany emerging diseases today aretick-borne. While heartwater affectscattle, sheep, goats and deer –not people – tick-borne afflictionslike Lyme disease and African tickbite fever do affect humans.Studying bont ticks may help incontrolling other disease-carryingticks, he notes.Burridge has been horrified bythe ease with which exotic tickstravel. In 1997, an injured tortoisefrom a reptile breeding facility inCentral Florida was brought toUF’s veterinary hospital fortreatment and, almost by accident,found to be carrying exotic ticks.With the United States responsiblefor more than 80 percent <strong>of</strong> worldtrade in live reptiles in the 1990s, thethreat <strong>of</strong> importing ticks via reptilesis very real.The tropical bont tick also couldjump borders by hitching a ridefrom the Caribbean to Florida ona migratory bird, like a cattle egret.Southern climates are ideal for theticks which, with wild deer as ahost, would be impossible toeradicate once they arrive.The UF team has focused much <strong>of</strong>its research <strong>of</strong>fshore. UF scientistSuman Mahan oversees the programin southern Africa, where much <strong>of</strong>the research has been successfullyfield-tested.On campus in Gainesville,pathobiology pr<strong>of</strong>essor AnthonyBarbet, who has had breakthroughsin the study <strong>of</strong> the tick-borne diseaseanaplasmosis, brings biotechnologyand its advances to the heartwaterteam. With Mahan and Burridge,Barbet has helped develop technologyfor a conventional vaccine that is onthe verge <strong>of</strong> being marketed.His focus now is on using geneticengineering to produce a recombinantDNA vaccine. Laboratory resultshave been promising, and the newvaccine would be the best tool yetin fighting heartwater.Biotechnology also has yieldedmore advanced diagnostic tests forheartwater. Previously, diagnosingheartwater required a difficult andcostly brain biopsy. In a hugeadvance, the UF heartwater teamhas developed two blood tests fordetecting the disease.“Heartwateris a potentialbioterrorism oragriterrorismagent.”Dr. Michael BurridgeAnother breakthrough has been intick control. Burridge and colleaguesinvented a bont tick decoy, whichcan be attached to the ear or tail orworn in a collar around an animal’sneck. The small, plastic tag attractsticks with pheromones then deliversa tickicide. The decoy lasts threemonths and eliminates the need forranchers to dip or spray wholeherds, which releases toxicchemicals into the environment.For tick control in wild animals,Burridge and his colleaguesdeveloped the AppliGator, whichcan be attached to a feeding troughand applies pesticide passively asdeer brush against it.Both the decoy and the AppliGatorare inexpensive and easy to use andthe AppliGator is stress-free bothfor animals and the people who needto treat them, Burridge said..Intervet International <strong>of</strong> theNetherlands, the world’s largestmanufacturer <strong>of</strong> large animalveterinary vaccines, is workingwith the UF heartwater teamto commercialize the vaccine.The Heartwater <strong>Research</strong>Program has spawned more thana dozen patents and attractedmore than $16 million in fundingfrom the U.S. Agency forInternational Development alone.Burridge says he is perhaps mostgratified by the scope andcompleteness <strong>of</strong> the project.“What we’ve done with thisheartwater project is unique inthe world. We’ve taken a diseaseand we’ve gone from the verybasic science <strong>of</strong> understanding itat the cellular level and moved onto applied science and then on tocommercialization <strong>of</strong> usefulproducts,” Burridge said. “I don’tknow <strong>of</strong> another project that hasgone from the subcellular level tocommercialization <strong>of</strong> products inthe field in quite the same way.”If – or when – the tropical bonttick jumps the U.S. border, theUF Heartwater <strong>Research</strong> Teamwill be ready.Photo left: Dr. Suman Mahan, left, andDr. Michael Burridge are shown with wild Africanbuffalo during a recent visit to South Africa.6<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Infectious Diseases • www.vetmed.ufl.edu7

Racing to Determine Causes <strong>of</strong> Greyhound DeathsAAt first, Florida greyhoundowners thought they had aparticularly tough case <strong>of</strong> kennelcough on their hands. Thengreyhounds started dying from themysterious respiratory ailment.For answers, the dog owners turnedto University <strong>of</strong> Florida immunologyand infectious disease specialistCynda Crawford.When Crawford beganinvestigating, she found an epidemic<strong>of</strong> nationwide proportions. By June2004, racetracks and kennels acrossthe country were reportinghundreds <strong>of</strong> sick greyhounds,causing quarantines and putting ahalt to racing in some locations.No one liked what came next.Crawford’s conclusion: equineinfluenza virus had jumped thespecies barrier from horses to dogs.“In the veterinary pr<strong>of</strong>ession, we hadnot identified influenza as a cause <strong>of</strong>respiratory disease in dogs before,”said Crawford, a researcher in UF’s<strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>. “Infact, it has not been described indomestic species other than horses,pigs, and poultry. But our DNAanalysis <strong>of</strong> the virus genome showedthat this virus actually jumped fromhorses to dogs.“When the influenza virus crossesa species barrier, it’s a big dealbecause you don’t know whichspecies will be next downthe line,” Crawford said. “Are peoplesubject to acquiring influenza fromdogs now?”Despite the surprising discovery, thediagnosis gave veterinarians a target.With the culprit identified,Crawford is now pursuing researchon a vaccine for prevention <strong>of</strong>infection and use <strong>of</strong> antiviral drugsfor treatment <strong>of</strong> sick dogs.Crawford works with a team thatincludes UF veterinary researchersPaul Gibbs, William Castleman andRichard Hill as well as researchersat the Cornell University <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> and thenational Centers for Disease Controland Prevention. She is also workingon developing a diagnostic assay toidentify infected dogs in hopes <strong>of</strong>catching the disease earlier.Crawford said respiratory diseaseoutbreaks are the top cause <strong>of</strong>illness in racing greyhounds, butthe severity and duration <strong>of</strong> theseoutbreaks led her to suspect anovel infectious agent.“In the past, these outbreakswould shut down greyhoundracing every five years or so,”Crawford said. “But they startedoccurring annually and lasted forseveral weeks.”Influenza is highly contagious,especially for dogs kenneled inclose quarters. It causes fever,coughing, nasal discharges andpneumonia, and can be fatal.Greyhounds have been dear toCrawford since her days as astudent in the UF veterinarycollege. “I adopted my firstgreyhound here,” said Crawford,who now owns three.The <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong><strong>Medicine</strong> has particular expertisein racehorses and racinggreyhounds through its Center for<strong>Veterinary</strong> Sports <strong>Medicine</strong> and isthe only veterinary college with itsown greyhound racing track.During 10 years <strong>of</strong> private veterinarypractice, Crawford ran a greyhoundadoption group for retired racers inTallahassee. <strong>Veterinary</strong> medicalresearch beckoned, however, so shegave up private practice andreturned to her alma mater. Her firstposting was in a laboratory forfeline immunodeficiency virusresearch and her work in that areacontinues today.Lately, Crawford and UF researcherJulie Levy have been working toidentify a diagnostic test thataccurately detects felineimmunodeficiency virus, or FIV,in cats. Cats infected with FIV areusually diagnosed by the presence <strong>of</strong>antibodies to the virus in theirbloodstream, and the tests availablefor detection <strong>of</strong> these antibodies are“When the influenzavirus crossesa species barrier, it’s abig deal because youdon’t know whichspecies will be nextdown the line.”Dr. Cynda Crawfordaccurate. However, the introductionin 2002 <strong>of</strong> a vaccine for protection <strong>of</strong>cats against FIV infection hascreated a problem for diagnosis.When a cat whose history isunknown shows up at a veterinaryclinic or animal shelter and testspositive for FIV antibodies during aroutine health screening, there is noother test available to verify whetherthe antibodies are due to infectionor vaccination.“We now have a diagnosticdilemma,” Crawford said. “Theantibodies the cat makes when it isvaccinated are indistinguishablefrom the antibodies the cat makeswhen it is infected with FIV.”It is important to identify theinfection because it is contagiousand lifelong. FIV-infected catsneed to be segregated from othercats to avoid spreading the virus,a procedure particularlyimportant in shelter catpopulations. Shelter cats also faceeuthanasia – instead <strong>of</strong> adoption– if they test positive for FIV,making an accurate diagnostictest a life or death issue.After three years, Crawfordsaid, a test to differentiatebetween vaccinated and infectedcats is no closer, but the workwill continue.Crawford also directs the blooddonor program at the UFveterinary teaching hospital,which provides blood productsfor transfusion <strong>of</strong> their dogand cat patients. Her researchis supported by grants from theWinn Feline Foundation, MorrisTrust Fund, Alachua CountyDepartment <strong>of</strong> Health and theDivision <strong>of</strong> Pari-mutuel Wagering.“I very much enjoy what I do.Every veterinary researcher’s bigdream is to contribute somethingthat improves animal health andwelfare,” Crawford said. “That’s alsomy big dream.”Photo left: Dr. Cynda Crawford and hercolleagues concluded in 2004 that equineinfluenza virus had jumped the speciesbarrier from horses to dogs.8<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Infectious Diseases • www.vetmed.ufl.edu9

Helping Frail Foals Survive“I see my missionas improvingequine health.”Dr. Steeve GiguèreWWhen he was a boy,the formula seemed simpleto University <strong>of</strong> Floridaresearcher Steeve Giguère:become a veterinarian, own ahorse, keep riding.Today, his research into equineneonatology brings him intocontact with plenty <strong>of</strong> horses,although he doesn’t own them orride them. But that’s OK withGiguère, who says he has founda new mission in helping frail foalssurvive. And he likes knowing hiswork makes a difference.“If you do clinics, you deal withhorses and their problems everyday,” Giguère said. “That way youknow what kinds <strong>of</strong> research reallywill help, as opposed to somethingthat is interesting fundamentally butnot really helpful clinically.”Since the mid-1980s, Giguère said,the UF <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong><strong>Medicine</strong> has built up itsneonatology program, publishingthe first equine neonatal text in1990. The university long has been atop referral center for clinical care <strong>of</strong>neonates and is playing a key role inequine neonatology research.“The discipline <strong>of</strong> equineneonatology started here,” Giguèresaid. “Every project helps inunderstanding better ways to treatequine neonatal diseases.”A big part <strong>of</strong> Giguère’s research isfocused on an anomaly that makesnewborn horses highly susceptibleto Rhodococcus, which causespneumonia, while adult horseslargely are immune to it.“With Rhodococcus, we are tryingto discover why only the babies getit, not adults. What is different inthe immune system <strong>of</strong> the babies?”Giguère said.Rhodococcus is the leadingcause <strong>of</strong> illness and death in foalsin the United States and theleading cause <strong>of</strong> pneumonia infoals from 3 weeks to 5 months<strong>of</strong> age. It is financially devastatingfor horse breeders, who sometimessee 40 percent <strong>of</strong> their foal cropcontract the disease. Foals thatdo recover are much less likelyto race as adults.Giguère says a long-term goal is todevelop a vaccine to protect foalsfrom Rhodococcus. But first, heneeds to find the reason for foals’peculiar susceptibility to theinfection. Preliminary results showthat the immune systems <strong>of</strong> adulthorses rapidly dispatchRhodococcus infections. Foals’immune cells, however, fail toreact, allowing Rhodococcus tocause pneumonia.“Rhodococcus lives in theenvironment, so it’s very difficult toget rid <strong>of</strong>. Oftentimes, foals don’tshow clinical signs till the disease istoo advanced,” Giguère said. “I wantto try to find better ways to identifythe disease earlier so we can starttreating it sooner. One day maybewe can prevent it, possibly with avaccine. It’s a big challenge. Sincethe infection occurs so close tobirth, there is a small window tobuild an immune response.”In his work in UF clinics, Giguèrefound himself faced with a need tomeasure blood pressure and cardiacoutput in critically ill foals, but withfew well-standardized, non-invasiveways to perform those tests. So heembarked on studies to find moreprecise and less invasive ways totake the measurements.In one study, he looked at theaccuracy <strong>of</strong> blood pressure monitorsand foals and he evaluated the effect<strong>of</strong> the site <strong>of</strong> cuff placement on theaccuracy <strong>of</strong> the measurements.He found that most blood pressuremonitors commonly used workedwell but found that the bestplacement for the cuffs was on afoal’s tail. The non-invasive monitorsare portable and easily used on thefarm or in a veterinary <strong>of</strong>fice.To improve methods to measurecardiac output in critically ill foals,Giguère decided to evaluate manynon-invasive methods. He foundthat ultrasound examination <strong>of</strong>the heart was very accurate inmeasuring cardiac output andeasily used without causing distressto the sick foals.Giguère also evaluated kitscommonly used on horse farmsto measure concentrations <strong>of</strong>antibodies in newborn foals.He found the kits varied widelyin accuracy and made his resultsavailable to veterinarians andfarm managers. Giguère also hasbeen studying multipleantibiotics for use in foals in anattempt to improve treatment<strong>of</strong> bacterial infections. Systemicbacterial infection is the leadingcause <strong>of</strong> mortality in foals.Giguère’s work has beenfunded by Morris AnimalFoundation and Florida’s Pari-Mutuel Trust Fund as well asthe Florida ThoroughbredBreeders’ and Owners’Association. In fact, support fromthe association allowed thecollege to establish a breedingherd <strong>of</strong> 17 mares that providefoals each year for research.Once the research is completed,the foals are adopted, Giguère said.“With access to the foals, we cananswer more questions so thebreeding herd is very important,”Giguère said. “These projects arepractical for the horse owner.“We can change the way wepractice, discover better therapies,”Giguère said. “I see my mission asimproving equine health.”Photo left: Dr. Steeve Giguère andveterinary care technician Maria Goremonitor a foal using ultrasound technology.10<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Infectious Diseases • www.vetmed.ufl.edu11

Seeking Solutions to Cat Overpopulation ProblemsUUniversity <strong>of</strong> Floridaresearcher Julie Levy has hereye on the big picture, a future inwhich there are no homeless catsbecause the cat overpopulationproblem has been solved.On her way to that future, Levyfocuses on today, sterilizing andvaccinating feral cats at monthlyclinics at UF’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>. OperationCatnip sterilizes and providesveterinary care each year for about2,000 cats, which are trapped,neutered and returned to theirenvironment. The low-costoperation – Levy and otherveterinarians, veterinary techniciansand students donate their time andthe college provides the facilities –is an attempt to make a dent in aproblem <strong>of</strong> almost staggeringproportions.Since 1994, Operation Catnip’s threechapters have sterilized more than20,000 cats, yet estimates put thenumber <strong>of</strong> homeless cats nationwideat about 70 million.“There is a huge cat overpopulationproblem,” Levy said. “A largenumber <strong>of</strong> strays are fed by peoplebut receive no veterinary care. Thesepeople are trying to make a situationbetter that they had nothing to dowith creating.“We can help by providing freeveterinary care for the cats.We’re the machine that makes it allwork,” Levy said. “Our clinics arefull every month.”Operation Catnip in Gainesville ismodeled on a trap-neuter-return,or TNR, program Levy startedwhile in graduate school at NorthCarolina State University. Similarclinics are scattered across thecountry and she concedes thatsurgical sterilization alone won’tend the overpopulation problem.But her outreach program has fueledher research. Levy evaluatescontraceptive vaccines for use inferal cats. A successful vaccinewould work by triggering antibodiesthat suppress fertility. One suchvaccine that had been used onwildlife did not work in feral cats,and Levy says much work stillneeds to be done. Her researchgroup currently is conductingstudies on another vaccine thatlooks more promising. Questionsthat need to be answered withcontraceptive vaccines include howsoon they work and how long theyprovide contraception.If a high percentage <strong>of</strong> feral cats ina colony can be sterilized – eithersurgically or with a vaccination –that will bring down the birth rateand eventually the population.“With feral cats, you may only getto see them once in their life,” Levysaid. “So what we’re looking for isherd immunity. And it will beimportant to have a product thatworks on both males and females.“It’s a population that is breedingcontinuously so somehow we needto increase our capacity to sterilize,”Levy said.Levy said few things spark acontroversy in a community the wayferal cats do. On one sideare cat-lovers seeking a humane wayto bring the population undercontrol. On the other side arewildlife advocates who say thatferal cats harm native animals likebirds by hunting. In between is alot <strong>of</strong> misinformation.For example, one community’sdebate on feral cats centered onthe notion that feral cats spreadrabies. Not so, says Levy. Wildanimals are the reservoir for rabies,and cats and dogs are incidentallyinfected during encounters withwildlife. To decrease the risk <strong>of</strong>rabid cats further, Levy recommendsvaccinating all cats that aresterilized in TNR programs.Levy also does research on felineinfectious diseases and says feralcats serve as a sentinel animal anda window on what pet cats mightface. So far, for example, surveys<strong>of</strong> cats exposed to West Nile virus,a mosquito-borne disease, show thatcats are commonly exposed to thevirus but seem to survive theinfection. Levy’s research alsoshowed that, contrary to a commonmisconception, feral cats are not morelikely than pet cats allowed outdoorsto be infected with feline leukemia,feline immunodeficiency virus andother common feline diseases.“Feral cats are a very poorlyunderstood population in terms<strong>of</strong> infectious diseases, systemicinfections, diseases that are athreat to other species or humans,”Levy said.The alternative to trap-neuterreturnprograms is euthanasia, apolicy that does not work, Levysays. Even if a community wanted toremove all its feral cats, whowould do it and who would payfor it, Levy asks. And studiesshow that as cats are removedfrom an environment, other catstake their place.Levy’s work on overpopulation<strong>of</strong> unwanted pets is so wellknownthat she was asked tojoin a team that went to theGalapagos for a wide-scale catand dog sterilization program in2004. In the past, the Galapagoshad used euthanasia for animalcontrol. In 2004, the islandersand the Park Service agreed totry neutering the animals.“In a lot <strong>of</strong> ways it was theperfect place to do this, with noanimals coming in fromsomewhere else to fill the void,”Levy said.After 15 years <strong>of</strong> working on the feralcat issue, Levy said she is beginningto notice more communities talkingabout the issue.“It’s a hugely controversial topic,but people are finally starting to dosomething about it,” Levy said.“<strong>Veterinary</strong> schools are an importantconnection for training veterinarystudents how to work safely withferal cats and how to contribute topet overpopulation solutions.“It is society’s problem; OperationCatnip is one solution,” Levy said.“Trap-neuter-return is an example <strong>of</strong>the really wonderful altruisticinstincts <strong>of</strong> human beings.“It’s the human-animal bond,” Levysaid. “We protect that.”Photo above: Dr. Julie Levy’s outreach program,Operation Catnip, has fueled her research.12<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Infectious Diseases • www.vetmed.ufl.edu13

Troubleshooting West Nile VirusIIn 2001, University <strong>of</strong> Floridaveterinarian Maureen Longbecame an expert on West Nilevirus almost by accident.That year, in clinics at UF’s <strong>College</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>, Long andother large animal medicineclinicians saw an increase in thenumber <strong>of</strong> horses coming in withthe mosquito-borne disease. Prior toits arrival in Florida, there had beenfewer than 100 cases <strong>of</strong> the diseasediagnosed in the United States.Intrigued, Long and her colleaguesput together a proposal that wasfunded by the Pari-mutuelWagering Trust Fund in Florida tostudy the disease outbreak. Thetiming could not have been better.The next year, 14,000 cases <strong>of</strong>the dreaded equine disease werediagnosed and the demand forLong’s expertise kept hercrisscrossing the country, makingher a national expert by the end<strong>of</strong> the year.Today, Long runs biosafety level 2and level 3 laboratories and isable to study the disease in horsesunder high-containment conditions.In just a few short years, UF hasbecome a leader in West Nileresearch in horses.“We became the go-to point by theaccident <strong>of</strong> seeing a lot <strong>of</strong> cases in2001 in our clinics,” Long said.“Now, we’re one <strong>of</strong> two places in thecountry to be able to house horses ina facility with special air flow andwaste decontamination, and withtwo labs that <strong>of</strong>fer the proper labworker protection.”West Nile virus causes encephalitis,both in horses and people, adding ahuman component to Long’sresearch. In horses, it has a 30percent mortality rate and there isno treatment. The virus affects thecentral nervous system andsymptoms can range from fever toparalysis to death. The level <strong>of</strong>infection in horses is important, too,because it’s an indication <strong>of</strong> whatpeople might face with the virus.Long’s research has spanned allaspects <strong>of</strong> the disease fromsomething as standard as buildinga database to more complicatedquestions such as why one horsedies and another survives. Long andher colleagues have investigatedtesting procedures for the FloridaDepartment <strong>of</strong> Agriculture andConsumer Services. All cases <strong>of</strong>West Nile in horses in Florida alsoare entered into a database <strong>of</strong>information obtained from a twopagequestionnaire filled out at thetime <strong>of</strong> testing.The U.S. Department <strong>of</strong>Agriculture heard about theUF work and funded a follow-upquestionnaire, which has becomethe foundation for research intothe types <strong>of</strong> horses, husbandryand management practices thatmay affect a horse’s chances <strong>of</strong>becoming infected withWest Nile and other mosquitoborneviruses in Florida. Theinformation collected – breed, age,vaccination history, clinical signs,location <strong>of</strong> the horse – is a valuabletool in tracking West Nile’sspread, Long said.The collected information alsorevealed that the horses thatbecome sick are not vaccinatedor not vaccinated <strong>of</strong>ten enough,leading to new recommendations,Long said.Other research investigates theeffectiveness <strong>of</strong> vaccines.“Currently marketed are the firstgenerationvaccines for West Nileand Eastern Equine Encephalitis,”said Long, referring to anothermosquito-borne disease. “What weneed now is a better class <strong>of</strong>vaccines for enhanced protection.“We need to explore questions likewhat makes a protected horse, whythe virus goes to the brain, whetherwe can breed for immunity,” Longsaid. “Another question is whichmosquitoes like horses comparedto birds and which mosquitoesalso share a taste for humans.Which mosquitoes are the biggestthreat? We don’t even know thatbasic information. A grant fundedby the charity <strong>of</strong> the Florida DerbyGala is assisting in research thatconsists <strong>of</strong> vacuuming mosquitoesdirectly <strong>of</strong>f horses.“Horses get thesame diseases wedo, so this is anexcellent model <strong>of</strong> ahuman/animaldisease.”“Horses get the same diseaseswe do,” Long said, “so this isan excellent model <strong>of</strong> ahuman/animal disease.”Dr. Maureen LongLong said the West Nile outbreakwas exciting because <strong>of</strong> theopportunities it <strong>of</strong>fered to godeeper into basic science andresearch and to collaborate withother UF experts on emergingdiseases, like virologist Paul Gibbs.But in the clinics, the disease onlybrought sadness.“During the first couple <strong>of</strong> years,I had vets with 30 and 40 years <strong>of</strong>experience calling from all over thecountry, extremely upset over thedevastation they were seeing,” saidLong, who has owned horses sinceshe was 5 years old. “There is notreatment, so it was really hard oneverybody. I felt very powerlesswhen people asked me if theirhorse would get better.”As West Nile has spread, otherveterinary colleges and researchinstitutions have turned to Longand her UF colleagues for adviceon how to set up highcontainmentresearch facilities tostudy newly emerging diseases.“Every veterinary school andevery region <strong>of</strong> the countrywas touched by thisoutbreak,” Long said. “It wasa phenomenal outbreak.”Although the emergency haspassed – there were only ahandful <strong>of</strong> West Nile cases in2004 – Long says Floridiansshould be braced for the nextoutbreak.“We’re stuck with the threat<strong>of</strong> new viruses in Florida because <strong>of</strong>our subtropical climate,” Long said.“We’re at risk <strong>of</strong> outbreaks from ourcommon diseases on a cyclical basisevery five to 10 years. Because we arean important import state we are alsoconstantly at risk for new infectiousdiseases that threaten our animals,whether pets or production animals.”Photo left: Dr. Maureen Long hashelped UF to become a leaderin West Nile virus research in horses.14<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Infectious Diseases • www.vetmed.ufl.edu15

Foamy Viruses Show Gene Therapy PotentialWhen University <strong>of</strong> Floridaresearcher Ayalew Mergia was agraduate student in the late 1980s,he became intrigued by foamyviruses.“The foamy virus may turn out“There was some interest in foamyviruses in the 1960s and early 1970s.However, since these viruses are notassociated with any disease,research into foamy viruses did notgain momentum,” said Mergia, apr<strong>of</strong>essor in the pathobiologydepartment <strong>of</strong> UF’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>. “None <strong>of</strong> uswere quite sure what to do with thisgroup <strong>of</strong> viruses.”to be an ideal modelfor delivering gene therapy,precisely because itdoes not cause disease.”So what do you do with a virus thatdoesn’t cause disease? Dr. Perhaps, Ayalew MergiaMergia answers, use it as atreatment for diseases.AAyalew Mergia has spent thelast 10 years working on a wayto use the foamy virus as a deliveryvehicle (vector) for gene therapy, theultimate goal being gene therapy forHIV patients. In gene therapy,desirable genetic traits are deliveredto a patient’s cells, which thenreplicate the desirable traits andstrengthen the body’s defenseagainst disease.“The foamy virus may turn out to bean ideal model for delivering genetherapy, precisely because it doesnot cause disease,” Mergia said.Mergia points out that some virusvectors now being studied for genetherapy have problems withefficiently delivering genes to targetcells. Others deliver genes but posepotential safety problems for use inhuman gene therapy. The idealdelivery system is a virus vector thatdoesn’t cause any <strong>of</strong> its ownproblems as it delivers the benefits<strong>of</strong> gene therapy to a patient’s cells.“With every vector you use,there could be some kind <strong>of</strong>problem. Remember, these vectorsare derived from viruses, and virusescan cause disease in humans,”Mergia said. “So maybe this iswhere the foamy virus may havean advantage. It appears to be safeand effective.”Already, researchers have studiedhumans who have contracted thefoamy virus accidentally fromanimals. These include hunters andanimal caretakers, whose cells showthe presence <strong>of</strong> the virus withoutany ill effects. There are no knowninstances <strong>of</strong> human-to-humantransmission <strong>of</strong> the virus, Mergiasaid, thus a gene therapy treatmentthat uses a foamy virus vectorshould not spread unintentionallyfrom the patient to other people.And animals that have the virusshow no ill effects, either.“There are many monkeys inprimate centers that are infectedwith the foamy virus, and they’rehealthy,” Mergia said. “Nothinghappens to them.”So far in trials with mice, Mergiahas used the foamy virus to delivermarker genes, which tell a scientistwhere the virus travels and whichcells the virus enters. The ultimategoal <strong>of</strong> Mergia’s research is to usethe foamy virus in gene therapy forHIV patients.Mergia’s work has been funded bythe National Institutes <strong>of</strong> Healthsince 1995.“We still have a significant amount<strong>of</strong> basic research we have toaccomplish for the next five yearsto make the foamy virus vector anefficient gene delivery system.Furthermore, we need to be careful.What if there is something thefoamy virus is doing that we haven’tdiscovered?” Mergia said. “Genetherapy is a promising novelapproach, and with an efficient andsafe gene delivery system will helpcure many diseases.”Photo top left: Dr. Ayalew Mergia, shown withpost-doctoral associate Dr. Nadja Matvienko,has focused on research that may one daylead to advances in gene therapy.Photo above: 293T Cells infectedwith Foamy Virus Vector containingGreen Fluorescent Protein gene.Photo bottom: Higher magnification <strong>of</strong> top image.16<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Infectious Diseases • www.vetmed.ufl.edu17

Charting New Territory With Immunodeficiency Virus <strong>Research</strong>Could cats,rather than dogs,be man’s best friend?When it comesto AIDS research,the answer might be yes.UUniversity <strong>of</strong> Floridaimmunologist Janet Yamamotosays the feline immunodeficiencyvirus, or FIV, has biologicalsimilarities to humanimmunodeficiency virus, or HIV,and those similarities could yieldadvances in efforts to develop anHIV vaccine.Yamamoto says she has “alwaysliked viruses.” In the early 1980s, sheworked on the virus that causesfeline leukemia and in 1986, she anda colleague discovered FIV, the virusthat causes AIDS in cats. Her workduring the 1990s culminated in anFIV vaccine that becamecommercially available in 2002.Yamamoto found her work on FIV<strong>of</strong>ten intersected with research onHIV. There are points in thestructures <strong>of</strong> both viruses, in fact,where the two are so similar thatresearch into one virus may help inresearch into the other.“We are working on a newgeneration <strong>of</strong> feline vaccines thatactually are made with HIVproteins,” said Yamamoto, whodirects the Laboratory <strong>of</strong>Comparative Immunology andRetrovirology at UF’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>. “We’ve foundthat HIV proteins are closely relatedto FIV proteins and are useful indeveloping an FIV vaccine, so thatleads us to ask whether FIV proteinscan help humans.”Immunodeficiency viruses have “agood side and a bad side,”Yamamoto said. People are familiarwith the bad, which leads to AIDS, adisease that has killed 22 millionpeople worldwide since it wasidentified in 1981, according toUnited Nations estimates.Yamamoto said the virus likes tohide its “good” side, which providesprotection against disease, making itvery difficult to isolate it. But inpeople – and cats – who have animmunodeficiency virus for yearswithout getting ill, the virus’ goodside is at work. These people andcats are called long-termnonprogressors and the strains theycarry may provide a key toprevention, therapy or even a curefor the disease.The work is painstaking. Imaginethat FIV and HIV are long ribbons.One section <strong>of</strong> the ribbon maycontain elements that cause diseaseor accelerate it. But the flip side <strong>of</strong>that section <strong>of</strong> ribbon may be “good”and hold elements that provideprotection against disease or retardthe disease. Then imagine five FIVribbons and two HIV ribbons.<strong>Research</strong>ers have found five distinctsubtypes <strong>of</strong> FIV, each with its owncharacteristics that had to beunderstood and studied beforemoving forward on a vaccine. Theprotective properties in thesubtypes had to be combined innumerous ways to bring out themost protective combination whilesuppressing the harmful properties.“We were about to give up on anFIV vaccine when we combinedsubtype A and subtype D,”Yamamoto said. “The overlap <strong>of</strong>those two gave us the protection wewere seeking.”Cats can’t get HIV infection, soYamamoto now is researching waysto use the protective elements <strong>of</strong>HIV in a feline vaccine. Her researchfound a protective section <strong>of</strong> HIVthat provides better immunity forcats than the protective sections <strong>of</strong>FIV. This section <strong>of</strong> HIV is sosimilar to FIV that it is usable in afeline vaccine. And since cats can’tget infected with HIV, the HIVproteins that promote disease inhumans do nothing to cats.Since the reverse is also true –humans can’t get FIV – she wouldlike to continue her work by lookingfor FIV strands that trigger animmune response in humanswithout promoting the disease.“It was important to find out thatHIV proteins are so closely relatedto FIV proteins,” Yamamoto said.“Hopefully, I can contribute to thehuman vaccine with my model.”Selecting the right strains to triggerimmunity in cats is much easier thandoing so with humans. AsYamamoto said, “In cats, we couldimmunize and watch. But there areno laboratory humans.”Yamamoto believes that tests withpeople who already have HIV wouldshow whether a vaccine developedfrom FIV could be useful as therapyand perhaps eventually useful in ahuman vaccine.“We have identified, so far, threeregions <strong>of</strong> FIV that are similar toHIV-1, and these FIV regionscould be tested with immune cellsfrom people who have HIV,”Yamamoto said. “If these regionsare recognized by the immune cellsfrom people with HIV, it wouldsuggest that those regions may beuseful as components for HIVvaccines for non-infected humans.However, more studies are needednot only in cats but also in monkeysto determine the significance <strong>of</strong>these FIV regions as componentsfor HIV vaccines.”Yamamoto spent much <strong>of</strong> 2004 andwill spend more time in 2005collaborating with colleagues at theUniversity <strong>of</strong> California at SanFrancisco and the University <strong>of</strong>Pittsburgh, as part <strong>of</strong> her strongbelief that teamwork will be the keyto further breakthroughs onimmunodeficiency viruses. Hervaccine work has been funded withmore than $3.4 million in grantsfrom the National Institutes <strong>of</strong>Health since 1989. She also hasfunded her research with more than$1 million in royalties from herpatents, including the patent on theFel-O-Vax FIV, which is marketedby Fort Dodge Animal Health, adivision <strong>of</strong> Wyeth pharmaceuticals.Yamamoto said she uses her patentmoney to explore ideas. When anidea bears fruit, she seeks grants.“NIH funding is taxpayer money, sowe need to repay it with discovery.”She personally repays some <strong>of</strong>her laboratory cats, veterans <strong>of</strong>bone marrow transplants, byproviding a home for them. But shewould like to see her feline studiespay <strong>of</strong>f for people.“Seeing animals and people livelonger, that’s why we do this work,”Yamamoto said. “I enjoy seeing myconcept and products help. It’sapplied research. I believe the catscan benefit not only cats, butpeople, too.”Photo left: Dr. Janet Yamamoto’s work on FIV<strong>of</strong>ten intersects with research on HIV.18<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Infectious Diseases • www.vetmed.ufl.edu19

Changing Standards <strong>of</strong> Care While Improving Sight“These animals can live without seeing,but they want to see.When you can give them sight,their personalities change big-time.”Dr. Dennis BrooksV<strong>Veterinary</strong> ophthalmologistDennis Brooks has fondmemories <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> his patients,such as a blind foal that ended up inhis University <strong>of</strong> Florida clinic a fewyears ago for an eye operation.“We were taking the baby back tothe mare, and when the baby got 10to 15 feet from the mare, the babydug in his hooves, just stopped, andwould not go any closer,” Brooksrecalled. “We were trying to pushthe baby gently toward the marewhen a student figured out theproblem. The baby had never seenhis mother.“It took him a minute or two, but thebaby figured out the huge animal infront <strong>of</strong> him was his mother,” Brookssaid. “It’s a big high to restore sight.”Brooks has spent a career workingtoward such success stories. He hasperformed cataract surgery on aBengal tiger and used laser surgeryto treat glaucoma in horses anddogs. At UF, Brooks and hiscolleagues have performed morecornea transplants on horses thananywhere else in the world.While some pet and horse ownersmay focus on more routine veterinarycare, vision problems are the fourthmost common health problem forhorses, and dogs are second only tohumans in incidence <strong>of</strong> glaucoma,making the need for veterinaryophthalmology research easy to see.Brooks has not only personallysaved sight for many animals, hisresearch has changed the standard<strong>of</strong> care other veterinarians providefor equine eye problems.“We’re right here in the middle <strong>of</strong>Florida’s horse industry, and in theearly 1980s we started seeing a lot <strong>of</strong>horses with eye problems at a timewhen no one was successful withhorse eye problems. Horse eyeproblems scared people,” Brooks said.“So we started working harder t<strong>of</strong>igure out why the horse eye healed sopoorly, how we could help it heal.”Eye problems in horses typically areworse than eye problems in otherspecies, including humans. Brooksand his colleagues figured anyadvances in treating equine eyesmight eventually benefit otheranimals and people. The researchersstudied tears collected from horses’damaged eyes and found high levels<strong>of</strong> enzymes. The enzymes, in effect,were causing the eyes to begindigesting themselves.“The horse eye is so destructive,”Brooks said. “But once we knew theenzyme level was up, we couldfigure out how to reduce the enzymelevel and allow the eye to heal.”The research was published inJanuary 2005 and resulted inchanges in the legal standard <strong>of</strong>veterinary medical care for horse eyeproblems. A veterinarian now mustaddress the enzyme level in a horsewith a damaged eye, and failure toaddress it amounts to a failure tomeet the new standard <strong>of</strong> care.“We’ve changed the legal standard<strong>of</strong> care for these animals, and I’mpretty proud <strong>of</strong> that,” Brooks said.Brooks’ research began withglaucoma in dogs. He was the firstto start examining how the bloodflow and blood pressure in the eyeaffects the optic nerve and currentlyis in the midst <strong>of</strong> a large grantproject to examine electricalchanges in the eye.“It requires a very large team <strong>of</strong>people to make contributions in thisarea,” Brooks said. “I’ll be studyingglaucoma my whole career. It’s a bigpuzzle, and what I’m trying to do isput some <strong>of</strong> the pieces together. I’mhoping someone comes along oneday and puts all the pieces together.”When Brooks’ career brought him toUF, he found himself in the midst <strong>of</strong>horse country and facing some <strong>of</strong> themost intransigent eye problemsaround. Not every horse’s eyesightcould be saved, but Brooks hasfound inspiration among the blindanimals as well.One inspiration, a plucky PalmBeach County thoroughbred namedValiant, competes in dressagealthough he is blind. Brooks tried invain to save Valiant’s sight and sayshe has been impressed by whatValiant and his owner haveaccomplished without sight.“A horse with no eyes can dobetter than you think,” Brooks said.The Valiant Equine Ophthalmology<strong>Research</strong> and Development Centeris named after the horse and helps t<strong>of</strong>und Brooks’ research.“These animals can live withoutseeing, but they want to see,”Brooks said. “When you can givethem sight, their personalitieschange big-time.”Brooks holds a veterinary medicinedegree and a doctorate, making himpart doctor and part scientist. Heteaches as well and has written atext called “Equine Ophthalmology.”He praises his graduate studentsand the university environment.“The graduate students make youbetter,” Brooks said. “If I workedall by myself, without colleaguesor students, I would not be doingnearly as well as I am in workingat a university.”While Brooks’ work appearsspecialized – only about 10veterinarians worldwide share hisexpertise – he says he doesn’t thinkhe has narrowed his focus at all.“I’ve opened a door to a wholeuniverse <strong>of</strong> knowledge,” Brookssaid. “It will keep me busy mywhole career.”Photo left: Dr. Dennis Brooks combinesscientific aptitude with clinical knowledgein veterinary ophthalmology.20<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Clincal • www.vetmed.ufl.edu21

Advancing Animal Reproductive HealthAAdvances in animalreproductive health havemirrored advances in humanreproductive health. Horses, forexample, get in vitro fertilizationand have ultrasound examinations<strong>of</strong> unborn babies, just like people do.While horse owners come to theUniversity <strong>of</strong> Florida’s ReproductionService in the <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong><strong>Medicine</strong> for such procedures, someare now <strong>of</strong>fered by veterinarianscloser to home. Where does thatleave UF’s Reproduction Service?Poised to take the next step intothe future, says service chiefMats Troedsson.UF has done its job when itpopularizes health care technologyfor animals, Troedsson said. Thepoint <strong>of</strong> developing new treatmentsis to get the advances into the hands<strong>of</strong> veterinarians.“People don’t need to come here forultrasound anymore,” Troedssonsaid, although they can, if they like.“So we will develop new assistedreproduction technologies.“And when those technologies arerefined enough to go into the field,we will be one step ahead, workingon the next technology.”Troedsson came to UF in 2002,attracted by the synergy betweenthe college’s clinical and researchfacilities. Being able to treat equinepatients and conduct research intotheir reproductive health issues, too,was a key for him. He is one <strong>of</strong> fiveveterinarian-researchers, threeworking on equine reproductiveissues and two on small animalreproductive issues. The staff isinternational: Troedsson grew upin Sweden, and recentlyresearchers from Poland andBelgium have joined the staff.“UF is one <strong>of</strong> the main veterinarycolleges when it comes to bothequine research and clinics,”Troedsson said. “The proximity <strong>of</strong>the horse-breeding center in Ocalahelps, too.”Troedsson’s research has focusedon equine endometritis, a leadingcause <strong>of</strong> fertility problems inmares. In fact, uterineinflammation affects about 15percent <strong>of</strong> mares, a high rate <strong>of</strong>incidence for any disease.Troedsson started out looking for thepart <strong>of</strong> the uterine defense mechanismthat was breaking down. He foundthat mares susceptible to endometritisdon’t contract the uterus in the sameway non-susceptible mares do.Susceptible mares were responding toan inflammation that caused them t<strong>of</strong>ail reproductively.At first, Troedsson thought bacteriacaused the inflammation. But hefound that sperm cells trigger anormal inflammatory response, too.In a normal mare, semen causesan inflammation that flushes outexcess sperm cells from the uterus.The inflammation is modulated,however, by seminal plasma, ensuringa healthy environment when a fertilizedegg descends into the uterus.In a susceptible mare, the inflammationprocess continued, causing the embryoto be lost. Troedsson currently is tryingto identify proteins in seminal plasmathat protect sperm cells.“We can sort outthe bad genesand savethe good genetics.”The work could lead to bettermanagement <strong>of</strong> mares who aresusceptible to endometritis.Dr. Mats Troedsson“In the past, we believed that seminalplasma was just a vehicle,” Troedssonsaid. “Now we recognize its importance.”Troedsson also is in the early stages <strong>of</strong>research into genetic testing <strong>of</strong> embryosto improve the health <strong>of</strong> future crops<strong>of</strong> horses.Nearly all horse breeds suffer from adisease unique to that breed. Quarterhorses have a debilitating musclecondition. American paint horses sufferfrom a genetic disease that kills foals justdays after their birth. The roots <strong>of</strong> thediseases are genetic, and the key to curingthem may lie in disrupting the geneticlink from generation to generation.Troedsson has started a project to domolecular genetic testing on embryosbefore they are implanted. Theresearch calls for removing single cellsfrom a five- or six-day-old embryoand testing the cells for geneticdiseases. Only healthy, disease-freeembryos would then be implanted inmares, leading to fewer geneticdiseases in future generations.“We can sort out the bad genesand save the good genetics,”Troedsson said. “There are somany diseases. So we have tomake a decision: What can theylive with; what are the genetictraits that are so desired?”Troedsson has collaborated withobstetricians and gynecologists atUF’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> andresearchers in the Department <strong>of</strong>Animal Sciences, as well as withveterinary colleagues who studyfertility issues in stallions.Although there are few majorgrants for equine research each year,he says the Reproduction Service hasbeen able to conduct research with arange <strong>of</strong> smaller grants fromorganizations like the AmericanQuarter Horse Association, theGrayson Jockey Club Foundation andinternal funding from the university.“It’s very difficult to get funding inequine research, with only a handful<strong>of</strong> national grants each year,”Troedsson said. “But I likespecializing in equine reproductionbecause it has great potential toapply basic research findings toclinical advances through assistedreproduction. It’s a very resultsorientedscience.”Photo left: Dr. Mats Troedsson’s researchhas focused on equine endometritis,a leading cause <strong>of</strong> fertility problems in mares.22<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Clincal • www.vetmed.ufl.edu23

Studying the Cough Mechanism“There are pr<strong>of</strong>oundregulatory differencesbetween coughand breathing.”Dr. Don BolserIIt’s a nagging, hacking,wheezing, gasping problem,and it’s the second most commonreason people in the United Statessee doctors, according to theCenters for Disease Controland Prevention.It’s the cough, a common problemthat is uncommonly complex, saysUniversity <strong>of</strong> Florida physiologistDonald Bolser.“It’s a difficult problem to deal withclinically,” said Bolser, a pr<strong>of</strong>essorand researcher in UF’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>. “Just because apatient is coughing doesn’t mean weknow why.“When I first started workingon this issue, I was amazed at howlittle information existed, howmuch fundamental informationis not known about cough andhow cough-suppressant drugswork,” Bolser said. “It seemsalmost any experiment I devisewill yield important andfundamental information.”Bolser is among the relatively fewscientists working on understandinghow and why we cough andwhether our treatments for coughdo what we think they do.“Codeine, for example, is one <strong>of</strong> themost widely prescribed drugs in theworld, yet we know relatively littleabout what it actually does,” Bolsersaid. “It doesn’t work on everyone,and when it does work, no oneknows exactly how it’s working.”The issue, Bolser said, is finding outwhich areas <strong>of</strong> the brain triggercough, then deciphering how theyfunction and react to drugs. He hasconducted research from both sides<strong>of</strong> the issue, working inpharmaceutical testing anddevelopment at Schering-Ploughand moving to UF to study thescience and physiology <strong>of</strong> cough.Breathing is controlled in thebrainstem, and scientists long havethought that the mechanism thatcontrols cough originates there, too.However, drugs that suppress coughhave no effect on breathing, sosomething more is at work. Bolsercalls it a hidden regulatory elementin the control system for cough.“What is the nature <strong>of</strong> thatelement?” Bolser asks. “We have alot <strong>of</strong> knowledge about breathingand the brainstem, and we knowthat the neural elements that governcough are restricted to thebrainstem, but there are pr<strong>of</strong>oundregulatory differences betweencough and breathing.”In one model Bolser has proposed,he theorizes that there may bepreviously unidentified neuronsthat are active only during a cough.These neurons may have remainedunidentified because they arelocated in a region <strong>of</strong> the brain notthought to be related to breathing. Ifthat turns out to be true, it presentsresearchers with a challenge both inunderstanding cough and treating it.The challenge is magnified furtherbecause different coughs – forexample, a laryngeal cough asopposed to a cough from theairways farther into the lungs – maywell be controlled differently by thebrain.Cough suppressants like codeineand dextromethorphan act onthe brainstem, but how theysuppress cough – when they do– is not known.Bolser is designing an experiment toinject codeine into the brainstem <strong>of</strong>laboratory animals to see where thecodeine goes to work. Making thelaboratory animals cough and thenfiguring out how to control thecough will yield new informationthat may eventually help in studyingcough in humans, Bolser said.Pharmaceutical companies recentlyhave turned their attention fromasthma medications to coughmedications, Bolser said.“Another medicine was not neededfor asthma,” Bolser said. “So theystarted looking at cough. Ourcurrent array <strong>of</strong> medicines isinadequate, even codeine, the onethought to be the gold standard.”Bolser collaborates with otherresearchers and UF’s own BrainInstitute. He said medical researchfunding organizations, such as theNational Institutes <strong>of</strong> Health, arereceptive to research proposals oncough, partly because they recognizehow unique the work is.“When you see someone cough,what are they actually doing?”Bolser asks. “We have to explore thefundamentals, how cough isproduced in humans and why drugs,while powerful, don’t always work.This is an emerging issue.”Photo left: Dr. Donald Bolser,shown with scientist Melanie Rose,is among the relatively few scientistsworking on understandinghow and why we cough.24<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Physiology • www.vetmed.ufl.edu25

Focusing on Breathing Awareness and DiseasePhoto top: Dr. Paul Davenport, shown in his lab with graduate student SarahPeiying Chan, is one <strong>of</strong> the few researchers in the college working on bothhumans and animals. Photo below demonstrates the use <strong>of</strong> a breathing device.IIt’s a common description,that something is as naturalas breathing.But for some children with severeasthma, breathing isn’t natural at all.In fact, these children can’t sensewhen they struggle with breathingand <strong>of</strong>ten end up in the emergencyroom on the verge <strong>of</strong> respiratoryfailure, said University <strong>of</strong> FloridaPr<strong>of</strong>essor Paul Davenport.For years, Davenport has beenstudying something most peopletake for granted: How youconsciously know you are breathing.For healthy people, it seemsautomatic, but the brain is still atwork, regulating respiration. Forsome asthmatic children, thosesignals from the brain are faulty.“If a patient can’t sense a problemwith their breathing, they can’tcompensate for it,” said Davenport, apr<strong>of</strong>essor in UF’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> since 1981.So Davenport and colleagues in theUF <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong> developedthe Respiratory Related EvokedPotential test in 1986. During thetest, a patient’s breathing isincreasingly impeded with amechanical device as scientistsmeasure brain wave activity andbreathing responses. The test helpsidentify children who lack theability to sense difficulty breathing,so they can be monitored and avoida life-threatening asthma attack.Asthma is the top chronic disease<strong>of</strong> childhood, and 60 percent <strong>of</strong> thechildren who have life-threateningasthma have a reduced ability totell the difference between a mildobstruction to their breathing and asevere obstruction, Davenport said.People who have had a double lungtransplant or spinal cord injuriesalso have trouble sensing difficultieswith their breathing.“For most people, if you stopbreathing for 2/10 <strong>of</strong> a second, itelicits a reaction,” Davenport said.“Most people can feel a chesttightness and treat themselves.”The reverse issue - patients who aretoo aware <strong>of</strong> their breathing, whichleads to anxiety and overuse <strong>of</strong>medication – also is a topic <strong>of</strong>research for Davenport.“One group can’t perceive breathingproblems, the other group ishyperperceptive about breathingproblems,” Davenport said. “So wewant to understand the physiology <strong>of</strong>breathing. If you can’t breathe,nothing else matters.”In the hyperperceptive group <strong>of</strong> asthmapatients, the anticipation <strong>of</strong> a futurebreathing problem leads to anxiety. Ineffect, they prompt a respiratory eventwith their anxiety and panic and end uprelying heavily on medication.“If you can’tbreathe,nothing elsematters.”Dr. Paul Davenport“Nothing bothers you more than thesense <strong>of</strong> suffocation,” Davenport said.“So these patients end up reaching fortheir inhaler at the slightest sign <strong>of</strong>tightening in their chests and end uptaking in more medication than theyneed to regulate their asthma.“We’re wandering into a brand newarea,” Davenport said.Davenport also has explored ways tostrengthen respiratory muscles andhas invented a device that amounts toa barbell for the lungs. The device canbe used for healthy people, like tubaplayers in a high school marchingband, and by people who havesuffered a loss <strong>of</strong> respiratory capacity,such as people on ventilators orvictims <strong>of</strong> spinal cord injuries. In fact,Davenport worked with actorChristopher Reeve and U.S. Navydivers in testing the device.One advantage <strong>of</strong> the device is thatit does not involve a drug; it’smechanical, so it can be used by justabout anyone.“We need to change the way welook at ventilation,” Davenport said.“We don’t want to just make apatient comfortable on abreathing machine, we want torehab because it is possible to dorespiratory rehabilitation.”Patients on ventilators have beenanesthetized and immobilizedand lose some <strong>of</strong> their respiratorycapacity. That leads to fear whenit’s time for them to breathe ontheir own. But with therapy tostrengthen their respiratorymuscles, 90 percent <strong>of</strong> thepatients who initially fail to weanfrom a breathing machine cancome <strong>of</strong>f ventilation.Although he’s a physiologist, nota veterinarian, Davenport is one<strong>of</strong> the few researchers in thecollege working on both humansand animals.“There are some questions wecan only address in humans andsome questions we can onlyaddress in animals,” Davenport said.“We can’t answer all the questionsin one species.”In addition to his research grantsfrom the National Institutes <strong>of</strong>Health and the American LungAssociation, Davenport also has wonthe Merck National Creativity inTeaching Award. He used the$25,000 grant to fund seminars oncreative teaching strategies.26<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Physiology • www.vetmed.ufl.edu27

Evaluating Treatments for OsteoporosisWhat Wronski has donewith the rats to furtherosteoporosis researchis groundbreaking.DDuring the last 15 minutes <strong>of</strong>the bone lecture in hismusculoskeletal course, University<strong>of</strong> Florida Pr<strong>of</strong>essor ThomasWronski talks about a topic hehopes will save his students’ healthdecades ahead. He lectures thewomen to get plenty <strong>of</strong> calcium andhopes the men will help the womenthey love do the same.“Women develop their peak bonemass at 25 to 35 years <strong>of</strong> age,” saidWronski, a researcher in UF’s<strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>.“So to avoid getting osteoporosisduring menopause, they need to bevery aware <strong>of</strong> getting calcium whilethey’re young.“I feel it’s just to take 15 minutesto educate them,” Wronski said.“If that little talk prevents just acouple <strong>of</strong> them from getting postmenopausalosteoporosis, that’smore important than what I dowith the rats.”That’s saying a lot, since whatWronski has done with the ratsis groundbreaking.Wronski has established an animalmodel with ovariectomized rats thatallows for the evaluation <strong>of</strong>osteoporosis treatments for humans.He has won awards for his workand sent an experiment into orbit onthe space shuttle.In his work, Wronski has shownthat ovariectomized rats becomeestrogen deficient just as women doat menopause and, like menopausalwomen, the estrogen deficiencycontributes to loss <strong>of</strong> bone density.The ovariectomized rats haveproven to be such a good animalmodel in bone density studies thatthe Food and Drug Administrationnow requires new osteoporosistreatments to be tested first inovariectomized rats before beingused in women.Wronski has played a key rolein validating the animal modeland helping evaluate severalosteoporosis treatments now onthe market.“In the mid-1970s, bone loss was notwell understood, and people had ahard time believing theovariectomized rat could be a goodmodel to use in osteoporosisresearch,” Wronski said. “In mywork since the mid-1980s, I’ve beenable to show that it is a good model.“Once the model was established, itcould be used to evaluatetreatments. Several drugs approvedby the FDA for osteoporosis wereevaluated in our studies here, sowe’ve been able to make acontribution, and it’s been a niceapplication <strong>of</strong> our research,”Wronski said.Wronski’s work with rats attractedattention from NASA in 1996, whenhe won a grant to send anexperiment up on the space shuttleto evaluate the causes <strong>of</strong> bone loss inspace. NASA doctors had noted thatastronauts returned from space withdecreased bone mass and wanted toknow if it was due to stresshormones, which inhibit bonegrowth, or lack <strong>of</strong> gravity, sincebones need to bear weight to remainhealthy.“It had always been thought thatstress increases levels <strong>of</strong>corticosteroids, which inhibits boneformation and leads to bone loss,”Wronski said. “So I decided totest that theory.”In Wronski’s experiment, six ratshad their adrenal glands removedto eliminate the source <strong>of</strong>corticosteroids and six kept theiradrenal glands. Their bone masswas evaluated upon their return.Based on the experiment,Wronski said it appears thatbone changes in space are causedby a lack <strong>of</strong> mechanical forcesrather than increased stresshormone levels.The National Institutes <strong>of</strong> Healthhas continuously funded Wronski’swork since 1986, and his currentgrant runs through 2008.The NIH also awarded him itsprestigious MERIT (Method toExtend <strong>Research</strong> in Time) award,which goes to fewer than 1 percent<strong>of</strong> investigators, for his sustainedcontribution to research on aging. Inmaking the award, the NIH notedthat Wronski’s work “represents asplendid example <strong>of</strong> how beautifullysimple good science can be whenthe investigator has the ability toask the right questions and do theright experiments.”Photo left: Dr. Tom Wronski, shown with laboratorytechnician Mercy Rivera, established an animalmodel with ovariectomized rats that allows for theevaluation <strong>of</strong> osteoporosis treatments for humans.Photo above: Laboratory technicianMelissa Rodriguez28<strong>Research</strong> • University <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Veterinary</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>••Physiology • www.vetmed.ufl.edu29