The colour of change - WaterAid

The colour of change - WaterAid

The colour of change - WaterAid

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Report<strong>The</strong> <strong>colour</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>change</strong>Innovation, motivation and sustainability in hygiene and sanitation work

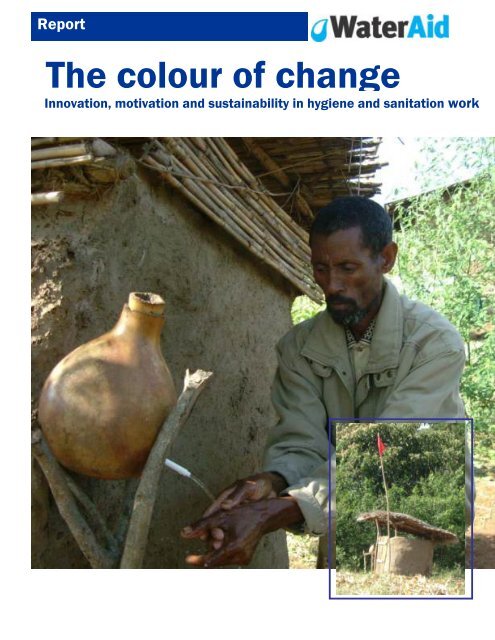

A success story in themaking?Achefer woreda is situated in AmharaNational Regional State in West Gojjam Zonearound 500 km north west <strong>of</strong> Ethiopia’scapital, Addis Ababa, and a couple <strong>of</strong> hours’drive from the town <strong>of</strong> Bahar Dar and itsfamously beautiful Lake Tana. This is the sitefor the Achefer woreda Water Supply,Hygiene and Sanitation programme,implemented by the Organisation forRehabilitation and Development in Amhara(ORDA), and supported by <strong>WaterAid</strong> (WAE),and the focus <strong>of</strong> this report: <strong>The</strong> <strong>colour</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>change</strong>.<strong>The</strong> title links to something that is unique inEthiopian WASH projects to date: Achefer’suse <strong>of</strong> <strong>colour</strong>ed flags as motivators forhousehold sanitation and hygiene practice.But this is just one <strong>of</strong> several innovationsseen in the project that makes it aninteresting case study to share.<strong>The</strong> report comes out <strong>of</strong> a four-day visit to theproject by a joint WAE-ORDA team inDecember 2006, some four months beforethe project was due to be handed over to thecommunity. Base-line surveys, participatoryevaluation exercises and mid-term reviewssince the project’s instigation in 2004 hadsuggested Achefer was a success story,outstripping many <strong>of</strong> its project targets. Thisvisit was an opportunity to analyse andunderstand this apparent success further.As such <strong>The</strong> <strong>colour</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>change</strong> aims to bringalive various aspects <strong>of</strong> the project andprovide food for thought. After a briefoverview <strong>of</strong> the project it considers some <strong>of</strong>the elements that might have helped to makeAchefer a success: the unique combination <strong>of</strong>circumstances and approaches in terms <strong>of</strong>the ORDA/WAE partnership and the project’sposition in relation to other work ORDA iscarrying out in the region; the unusual staffingmodel; the holistic nature <strong>of</strong> the projectcomponents. Perhaps above all the reporthighlights some <strong>of</strong> the innovative andmotivating sanitation and hygiene promotionmethodologies.Front cover: Sisay Berhanu hand-washing afterusing the latrine. <strong>The</strong> project awarded his householdwith a red flag for sanitation and hygiene.Asnapshot<strong>of</strong>Achefer:childrencollectingcleandrinkingwater fromthe newWAE/ORDAcommunityhandpump.<strong>The</strong> second half <strong>of</strong> the report considers howsome <strong>of</strong> these components and mechanismsmight look in the future once the project ishanded over to the community. Clearly thetime to measure overall sustainability will bean in-depth evaluation in several years time.But for now the fairly raw snapshot providedby <strong>The</strong> <strong>colour</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>change</strong> should encouragediscussion around issues such as thesustainability <strong>of</strong> promotion work, thesustainability <strong>of</strong> <strong>change</strong>d hygienic practice,the way in which community and woreda canwork together, and so on. At the request <strong>of</strong>Achefer woreda colleagues, the report alsoincludes two “practitioners’ toolkits” (pages7&12 and 9&10) which can be separated out(by opening the central staples) as trainingand motivational aids for the community.Abbreviations and explanationsWAEORDAworedakebelegoteWASHWRMHEWHPVHC<strong>WaterAid</strong> in EthiopiaOrganisation for Rehabilitationand Development in Amharadistrictsmaller administrative areagroup <strong>of</strong> households/villageWater Supply, Sanitation andHygieneWater Resource ManagementHealth Extension WorkersHygiene PromotersVillage Hygiene CommunicatorsA <strong>WaterAid</strong> report.Written by: Polly Mathewson (independentconsultant) and Manyahlshal Ayele (WAE)Research team: Manyahshal Ayele (WAE),Dr Abdu Zeleke (WAE) and Polly Mathewson.Key informants: Tesfaye Yalew and WalleSetotaw (ORDA).Driver: Tekele Ekubu (WAE)Date : January 20081

Achefer: an overviewAchefer woreda is typical <strong>of</strong> the estimated 43per cent absolute poverty levels (ORDA-WAEreport, 2004) and agricultural subsistencelivelihood strategies <strong>of</strong> the rural population <strong>of</strong>the wider Amhara Region. School drop out ishigh in the woreda either because childrenare needed for labour or due to sickness:malaria and other water related diseases arethe main culprits.<strong>The</strong> woreda is mostly plain, with someundulating areas (see photo, left). <strong>The</strong>re aremany streams and swampy areas fed byground water connecting variously to LakeTana and rivers that later join the Blue Nile.Despite the abundant water resourcepotential in the region, prior to the projectalmost 88 per cent <strong>of</strong> the rural population <strong>of</strong>Achefer lacked adequate and safe water fordrinking and domestic uses, including forlivestock consumption. In addition betweenDecember and May most <strong>of</strong> the existingsources dry up altogether forcing women andchildren to travel long distances for water.Limited access to unprotected sources hascaused ill health, lost work time and reducedschool attendance, as well as created conflictin the area. Meanwhile a government study(Rural HH socio-economic survey, 2002)showed that only 2.3 per cent <strong>of</strong> the woredahad access to sanitation facilities, thoughobservation at field level by ORDA-WAEindicated that latrine coverage in the projectarea was almost nil (0.2 per cent) with properhygiene and sanitation practice andawareness extremely low.<strong>The</strong> ORDA-WAE project was devised to meetthe challenges <strong>of</strong> the area using many triedand tested components. ORDA’s impressivetrack record <strong>of</strong> effective water supply deliverywas married with the experience WAE couldbring from their insistence on alwaysintegrating sanitation and hygiene promotionwith water supply. Other elements wereborrowed from projects in other regions andcountries, and from other partnerships,including employing Hygiene Promoters,awarding flags as incentives, using Video forpromotion work and providing training inhorticulture. Each component will be exploredin detail, but the box (left) gives an overview.Project facts and figures• Achefer woreda population: 344,000• <strong>The</strong> project area covers 6 kebeles:Kongerie, Ambeshen, Kualabaka,Kurbeha, Lihudi and Dilamo, with a totalpopulation <strong>of</strong> 40,623• Project <strong>of</strong>fice: in Yismala town• A three year project: 2004-2007• Project staff/voluntary groups:1 Project Coordinator/Sanitarian,1 Construction Foreman, 2 guards10 paid Hygiene Promoters (HP),7 voluntary Village HygieneCommunicators (VHC),155 WATSAN Committee members,48 Caretakers/guards• Water supply components:Hand Dug Well, Gravity Spring,Spot Spring Development and CattleTroughsWater source protection/rehabilitationPromotion <strong>of</strong> horticultural activities• Sanitation/hygiene components:Model Traditional Pit Latrines (TPL)TPLs built by villagersRefuse Disposal Pits (RFP)Hand-washing at household levelCommunal showers and clothes washingbasinsHousehold improvementsHygiene promotionCommunity development training• Planned project beneficiaries: 29,400sanitation, 17,410 hygiene, 9,130 water(rising to 18,000 water by project end)2

Reasons for success?A holistic vision, energyand a spirit <strong>of</strong> innovationVisiting the phase I project a few monthsbefore its completion, there were clearsuccesses to note: for example 27 waterschemes had been built as opposed to theplanned 22. <strong>The</strong> reason given for this by theproject team was the enthusiasm <strong>of</strong> thecommunity for clean water and their matchingthis with a commitment to give their time andlabour freely, and to contribute funds. <strong>The</strong>project <strong>of</strong>fice had received 30 furtherrequests for water works, villagers havingorganised committees, elected a chairpersonand put money into a bank account beforesubmitting their applications. Whilecommunities are <strong>of</strong>ten eager for water, Acheferwas having wide success with latrineconstruction, with many gotes (groups <strong>of</strong>households) nearing 100% sanitation coverage.As much as this, many people were working toachieve the full quota <strong>of</strong> hygiene and householdcomponents promoted by the project, such astwo hand-washing facilities, clean clothes andcompounds, fuel-efficient stoves, solid wastepits and vegetable gardens. What then wasdriving such enthusiasm and activity?Achefer seems to derive much <strong>of</strong> its successfrom the sense <strong>of</strong> “vision” behind the projectand the attitude in realising this vision thatoriginates with the project team. This in turnis supported strongly by ORDA and WAE,and the project team has inspired a similarspirit in the wider team and community. <strong>The</strong> two permanent ORDA staffmembers have personalities that demand <strong>of</strong>themselves a high level <strong>of</strong> commitment to thecommunity and their work, but they also sawthe project as an opportunity to trial newmethods that they may not have been able todo in previous more closely circumscribedwork places (e.g. innovative hygienepromotion methods). This was a chance bothto be more effective and to further theirpersonal pr<strong>of</strong>essional development. Workingas a uniquely small core team with limitedresources has had the disadvantage <strong>of</strong> workoverload, but the advantages <strong>of</strong> flexibility,and more independent and creative thinking.WAE’s DrAbdu Zelekewith atraditionalwater-liftingdevice. Havingseen such adevice used inBenishangul inthe south west<strong>of</strong> Ethiopia, hehelpedintroduce thesimple,replicabletechnology toAchefer. WAE’s growing ethos is to embraceinnovative ideas in its work with partnerorganisations: to look beyond the obvioussolutions, whilst trying to ensure new ideasare backed up with appropriate systems.In Achefer the partnership with ORDA wasitself experimental (see page 4) and based ona desire to integrate water with hygiene andsanitation – that part <strong>of</strong> WASH which timeand again proves difficult and requires extraenergetic thinking and persistence inimplementation. <strong>The</strong> project was conceived in aholistic manner, so that hygiene andsanitation was extended beyond latrines andhand-washing to improved householdmanagement and devices. Water supply wastaken in the direction <strong>of</strong> Water ResourceManagement, so that communities could seethe future potential <strong>of</strong> water run <strong>of</strong>f forcommunity conservation or incomegenerating horticultural projects. Andindividual households were encouraged toimprove their nutrition and make use <strong>of</strong> easilyaccessible ground water for vegetable plots.<strong>The</strong> project staff took their own initiativebeyond plans in the project documents, suchas providing training in food preparation forvegetables previously unknown in the area. Effectively designed managementstrategies for the wider project team werecertainly strengthened by the tireless supportvisits, accessibility and good communicationskills <strong>of</strong> the two core project staff, as reportedby the HPs, VHCs, Water Committees etc.3

Reasons for success?A tight team and a newpartnership model…As mentioned the key project team forAchefer has been two people – a projectcoordinator/sanitarian and a constructionforeman. Through necessity they alsocovered the work <strong>of</strong> secretary, storekeeperetc. <strong>The</strong>re are two guards and very recently acleaner has been recruited. Comparing thistight team with the demanding nature <strong>of</strong> the jobin the project sites, it is doubly surprising towitness the successes <strong>of</strong> Achefer. In additionthe budget for Achefer allocated by WAE wasminimal. Does this make Achefer a costeffective“miracle model” showing that “smallis indeed beautiful” as the saying suggests?Unpacking the realities behind the situationreveals a more complex picture and shedslight on the variety <strong>of</strong> models possible inWASH projects.Clarifying Achefer’s situation<strong>The</strong> reality is that for most <strong>of</strong> the first twoyears the Achefer project only had the projectcoordinator-sanitarian as a permanent staffmember, the foreman joining at the end <strong>of</strong> thesecond year. For these twenty months thesanitarian worked with the voluntary VHCs. Athis request, and after evaluations, paid HPswere employed (a fairly recent model used inTigray, northern Ethiopia, by WAE’s partnersthe Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Oromiaby Water Action), as well as a permanentforeman.However Achefer has had the support <strong>of</strong> arange <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionals from a pool <strong>of</strong> staff atORDA’s head <strong>of</strong>fice in nearby Bahir Dar,including geologists, engineers and techniciansloaned for short periods for the water supplycomponent <strong>of</strong> the project.Although the funding for Achefer from WAElooked remarkably little - £14,000 for the firstyear, £30,000 for the second and £40,000 forthe third - the monetary value <strong>of</strong> ORDA’sdeployment <strong>of</strong> existing personnel toAchefer has to be factored into the real costs.<strong>The</strong> community also contributed cash andlabour that amounted to around 20-30% <strong>of</strong>the overall project costs, as well as a greatdeal <strong>of</strong> labour. With only a skeleton team attheir compound, the Achefer project had lessaccess to vehicles (<strong>of</strong>ten a high cost inprojects) than is customary. ORDA hadnegotiated a motorbike loan from the woreda<strong>of</strong>fice for the first months <strong>of</strong> the project, butcomplications with this meant that there wasa great deal <strong>of</strong> time when the sanitariantravelled through the six kebeles on foot. Atthe first 6-month review, WAE provided adedicated motorbike to the project.<strong>The</strong> question is why such a tight budget andteam was decided upon, what the positiveand negative consequences have been andwhether this model is one to replicateelsewhere. <strong>The</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> employing HPs isconsidered later in relation to promotion andsustainability.ORDA and WAE<strong>The</strong> Achefer project was a new departure forORDA. ORDA has a reputation for their abilityto mobilise the community and deliver waterservices, but they have not been successfulin integrating water with sanitation. MeanwhileWAE saw the opportunity in ORDA towork more closely with an organisation thatusually worked with larger donors than WAE.Perhaps this was an opportunity to influenceORDA and its more regular donors to take onan integrated water, sanitation and hygieneapproach. However, WAE invested little in theproject in order to re-test the capabilities <strong>of</strong>the two organizations working together whichwas tested earlier with two small projects inAngolela Asagirt and Moretna Jiru areas.ORDA meanwhile had a range <strong>of</strong> ongoingwater projects in the area and was able toProject construction foreman Walle Setotaw, withthe motorbike and trailer. Such motorbikes can beunstable on rough terrain.4

provide water supply quite easily, but workingwith WA and on sanitation was a newchallenge, especially with their limited budget.<strong>The</strong> Achefer project required reassessmentand redesigning as the partnership clarifiedand the team found its strengths andlimitations, and flexibility in this from bothorganisations has been important. <strong>The</strong> initialthinking had been to employ a water engineeras the coordinator for the first year and then aconstruction foreman and sanitarian for thesecond year. ORDA however argued thatwith only 10 or so water schemes constructedper year, a full-time engineer would be awaste <strong>of</strong> resources when they could loan onefrom head <strong>of</strong>fice. In time it became clear thata more appropriate staff person for watersupply would be a construction foreman, i.e. -a middle level technical support person forthe day-to-day work and communitymobilisation. Meanwhile the skills andcharacter <strong>of</strong> the sanitarian worked well in thecoordinator role, and perhaps having asanitarian in this post was an importantbalance for the project beside the loanedpr<strong>of</strong>essionals working on water.An evolving modelAs the staffing evolved over time, with theaddition <strong>of</strong> paid HPs and foreman, so theproject components evolved by virtue <strong>of</strong> theProject Coordinator’s innovations and bothorganisations’ responsiveness to these.Elements that have become standard inAchefer by the third year took time tocrystallise. WAE had suggested othercomponents such as clothes washing basins,shower and cattle troughs could be built asmodels if the water were sufficient, but theyare now considered part <strong>of</strong> the project.Likewise gardening was suggested by ORDAbut the detailed activities evolved with theproject staff, as the water lifting devices weresuggested by WA and have now becomepopular. Household improvements such asfuel saving stoves grew out <strong>of</strong> plannedcomponents such as keeping the compoundclean and waste disposal pits, graduallyforming a holistic project that considered afamily’s wider needs for a healthy life.Initially there was a small budget forpromotion work <strong>of</strong> around £600 (10,000Ethiopian birr), but the Project Coordinatorrequested more. He wanted to introduce ac<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony gathering (see box on page8 for more on this cultural tradition) that wouldbring community members together and allowtraining and discussions on hygiene andsanitation. But he also wanted to introduceexternal technologies to these gatherings notusually encouraged by WAE: requesting atelevision, video player and generator. To trialthe c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony promotion method theProject Coordinator actually started withmoney from his own pocket, before formallyrequesting a small budget for this from WAEand ORDA. A budget was also required for asystem <strong>of</strong> incentives that evolved.Getting the balance rightFor ORDA this was the first time to be sostrongly involved with hygiene and sanitation,for WAE it was the first time to work with anorganisation with a crew <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, andthus have the option <strong>of</strong> a small project team.Achefer appears a good model both for waterand for hygiene and sanitation work, and thefluid evolution <strong>of</strong> its components and staffinga useful experience in adaptation and trial. Atight team with close community relationshipsand an efficient, strategic use <strong>of</strong> a limitedbudget are positive lessons to take forwards.On the other hand the personal load on s<strong>of</strong>ew staff has been considerable. <strong>The</strong>question is could one or two additional staffhave resulted in proportionately greatersuccess, especially in terms <strong>of</strong> completingwork before project phase out? <strong>The</strong>re seemlessons in balancing cost-effectiveness withthe minimum requirements for efficiency andfor fairness. Clearly ORDA, with its crewavailable for short periods, is unusual. ForWAE, many <strong>of</strong> its partners are at a muchearlier stage <strong>of</strong> maturity and have fewerresources at their disposal, while others havewell-established strategies for large projectswith teams <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionals employed on site.But Achefer does raise questions aboutdifferent models, not least can pr<strong>of</strong>essionalstaff in certain roles be shared, or can certainroles, e.g. guard and storekeeper, double up?5

Reasons for success?Community mobilisationthrough innovativemethods, incentives, anda paid promotion teamAn integrated approach to hygiene andsanitation promotion has been key to thesuccesses <strong>of</strong> Achefer. This page gives anoverview <strong>of</strong> the promotion work. Pages 7 and12 form a pull-out poster, which aims to drawthe promotion tools together as a training andmotivating aid. On page 8 Achefer peoplegive their perspective, while challenges likecost and sustainability are debated later on.C<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony: <strong>The</strong> project team believethat community acceptance has been thesingle most critical strength <strong>of</strong> the project.<strong>The</strong>y attribute the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony theyintroduced as one <strong>of</strong> the keys to establishingthis sense <strong>of</strong> trust. As a traditional socialoccasion within Ethiopian society, c<strong>of</strong>feeceremonies have been used to bring peopletogether in various projects. However, it wasProject Coordinator Tesfaye Yalew’s idea totrial them for sanitation and hygienepromotion and he set about organising thesesix months after the project started. With nobudget allocation at first, he experimentedusing his own money to provide just c<strong>of</strong>feewithout sugar. He imagined the meetingswould attract women with their children, butfound men attended as well. Tesfaye thenrequested a budget so each gote (more thanProjectCoordinator,TesfayeYalew, withtools theproject awardsto individualsfor exceptionalprojectparticipationand positive<strong>change</strong>. <strong>The</strong>seincentives orrewards aregiven out atthe c<strong>of</strong>feeceremonies.Achefer’s Hygiene Promoters: HPs divide up theproject area and each manage a small team <strong>of</strong>VHCs. <strong>The</strong>y must be 12 th grade graduates, haveexperience in community mobilisation or healthwork and pass the project training course. <strong>The</strong>y arepaid 300 birr per month. HPs train house to houseand at the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremonies, covering all aspects<strong>of</strong> latrine construction and hygiene promotion.50 people) in the project area could attendregular ceremonies with formal trainings anddiscussions. <strong>The</strong> project staff, HPs, VHCs,elders, and others speak and people readpoems that they have composed.Video: Another innovation has been filmingthe successes <strong>of</strong> community hygiene andpromotion work to show on the projecttelevision set. <strong>The</strong> short films document thechallenges people have overcome in one orother gote, and record the positive <strong>change</strong>sas ways to motivate and inspire others in theproject area. <strong>The</strong> films are shown at thec<strong>of</strong>fee ceremonies together with traditionalmusic and dance videos.Incentives – flags, sweets, and tools:Use <strong>of</strong> flags to encourage latrine building isan idea borrowed from WA Bangladesh.Tesfaye, his team and WAE staff discussedpiloting a similar method with somemodifications in Achefer to encourage latrinebuilding primarily, but also hand-washingsystems, compound cleanliness etc. Aftersome experimentation red, green and whiteflags were chosen with the project <strong>of</strong>ficeawarding them according to the componentspeople had achieved, with the possibility <strong>of</strong>upgrading, and downgrading (for neglect).Sweets are given to children for clean clothesand faces, tools to active households and theschool plans to give exercise books and pensfor children making particular effort.6

Practitioners’ toolkitIdeas for….INCENTIVESAwarding <strong>colour</strong>ed flags for householdsanitation and hygiene:Hygiene Promoters, Village Hygiene Communicatorsor Health Extension Workers working together withWASH committees and community members may liketo introduce a flag incentive/award system toencourage people to improve personal and householdsanitation and hygiene.Mostly people will be motivated by their own sense <strong>of</strong>achievement in receiving a flag for their efforts (andthe chance to move to a higher level <strong>of</strong> flag). <strong>The</strong>public nature <strong>of</strong> the award creates an additionalcompetitive edge. It is best to decide on categoriesand flag <strong>colour</strong>s together as a community. Whatworked in Achefer were three flags: red, green andwhite. This might be a starting point for discussions.To get a red flag in Achefer you need:• A latrine (safely built & well maintained)• A hand washing facility beside the latrine andideally beside the house door too(a jerry can and tap, or local version –e.g. a gourd with pen tap).• A dry waste disposal pit• Home and compound cleanliness• Family hygieneFor a green flag you need three <strong>of</strong> these (but certainlya latrine and hand-washing) and for the white flag twocomponents (but certainly a latrine).<strong>The</strong> promotion workers encourage and supporthouseholds, assess their progress and then flags areawarded at a community ceremony. Flags can beupgraded as people improve or downgraded if theyneglect things. From a sample group questioned inAchefer, 56% said they found the flag systemencouraging, 32% found it created a positive sense <strong>of</strong>competition and 12% found it community spirited. Inthis case none felt negatively towards the flags. But itis good to run a pilot, and see if people like it.Checking thecleanliness <strong>of</strong>children’sclothes andgiving sweetsas rewards forgood hygienehelped otherchildren learn. Awarding tools, sweets, washingpowder,or exercise books andpens, for personal achievement:During their promotion and mobilisationwork in Achefer project staff observe thecleanliness <strong>of</strong> household compounds,randomly check herding children’sclothes, hands and faces when theymeet them, visit the school regularly andtest the children’s knowledge <strong>of</strong> hygienepractice, and observe families atcommunity meetings. <strong>The</strong> staff use theseopportunities to encourage people andtrain them, but also to reward them withappropriate items if it is clear they areadopting day-to-day and long termbehavioural <strong>change</strong>s necessary for goodhygiene and sanitation. Children willreceive sweets; students receiveexercise books, mothers washingpowder.During the construction phase(<strong>of</strong> water systems) highly committedindividuals are given tools to cultivatetheir plots with vegetable seeds providedby the project.Incentives can increase personal andcommunity pride and encouragecompetition. A project or communityneeds to consider how to organise abudget for such items, and decide howlong it is necessary to run an incentivescheme for it to have long-term impact.7<strong>WaterAid</strong> in EthiopiaP.O.Box 4812, Addis AbabaTel: 251 114 661680Fax: 251 114 661679www.wateraidethiopia.org7

Discussing.. promotion, incentives & c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremonies.FitfitaeTechelo(left)KualabakaSchool:“<strong>The</strong> hygiene promotion has to continue asthere are still some people who do not thinkthat this is important. <strong>The</strong>y (ORDA) areteaching us about water cleanliness, latrines,household compound cleanliness, regardingenergy saving stoves. <strong>The</strong>y did this bycoming to each household, and at the c<strong>of</strong>feeceremony place. Here people who haveperformed well or have good experiences areinvited to share their experience and aregiven awards e.g. a flag. On weekends, whenthere is no school, the children play togetherand move from one house to the other andwhen they see a red or green flag, theyappreciate it and go back to their parents andask their parents to have the same flag. In myschool, for example, most students know thatwe have a red flag and some come to me andsay how much they like that. <strong>The</strong>y say‘tadelesh’ - you are lucky.”Yirdaw Amare(right), also fromKualabaka School:.“I once answereda question andwas given a candyby Tesfay (ProjectCoordinator).I was so glad.I know the candy is so small but itindicates that if I work hard, I can even getbigger awards. In the school you compete.One will become a genius and gets an awardand the others won’t. It is like that. If peoplewant to get the flag or any other award, theyknow they have to work hard. If not, it isobvious that the others who did well will get it.About sustainability? Well you know a childstarts to learn and when he/she completeseducation, they become a teacher, a doctoretc. but they do not go back to illiteracy. It islike that. My impression is that my parentsand others will continue to practice the lessonthey got from ORDA and will also shape thefuture generation.We are now used to the clean water. I onceremember, I was tired and asked someone togive me water to drink and they gave mewater from the spring. <strong>The</strong>n I got sick. Evenour stomach is now used to the clean water.We didn’t give attention to such things before.Now we are not sick anymore.”TangutReta (left)is a VHCfor Sekutgote,Kualabaka:“Before we started to build - that’s a year ago- everyone was defecating everywhere anddrinking polluted water. I had seen a latrine inBahir Dar but I did not know how to make oneand I didn’t know the connection betweenlatrines and health until after the projecttraining. <strong>The</strong> community selected me as aVHC because I work hard, keep myself cleanand am organised. I work every day with theother staff. We blow a trumpet to call peoplefor the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony. Everyone comes,unless they have commitments. <strong>The</strong> projectsupplies the c<strong>of</strong>fee and we all take food.<strong>The</strong>re is the training. <strong>The</strong>n the communitylikes to stay on and chat, even if Tesfaye andthe others have to leave. It’s like a picnic.”<strong>The</strong> Ethiopian C<strong>of</strong>fee Ceremony is unique. C<strong>of</strong>feeis generally reserved for special social gatherings.Usually fresh grass or flowers are spread on theground; a woman sits on a low stool <strong>of</strong>ten with twosmall charcoal burners – one to prepare the c<strong>of</strong>feeand the other heating fragrant incense. Firstly freshbeans are roasted and the smoke wafted towardseach guest for them to enjoy the aroma. <strong>The</strong> beansare then ground by hand and added to water in atraditional clay c<strong>of</strong>fee pot, with leaves (in someplaces) acting as a stopper. <strong>The</strong> c<strong>of</strong>fee is boiled upand served three times, poured each time from highup into small ornate cups, and served with toastedgrain or pop-corn. <strong>The</strong> atmosphere created isrespectful to guests, sociable, and also poetic.8

Practitioners’ toolkitIdeas for…. Improved stoves: Removing thecooking fire from the home means lesssmoke indoors which reduces eye andrespiratory health problems. Raising thestove reduces back pain. This easilyreplicable model made from mud andstraw uses far less fuel wood than an openfire. A separate kitchen does not need tobe expensive: this is a simple semi-circularventilated shelter. Mud and straw can alsobe used to build shelves into the walls tokeeps utensils clean, and as people gainconfidence, they can use it to make s<strong>of</strong>as.AT HOME Water-liftingpulley for vegetables:In areas with accessibleground water a smallwell in the compoundcan produce water forgardening (but not fordrinking, unless it istreated). <strong>The</strong> design forthe pulley comes fromthe south west <strong>of</strong>Ethiopia but is easilyreplicable usingeucalyptus wood. <strong>The</strong>sephotos can help anyone Hand-washing at home:Promote having clean water (andsoap) on a shelf outside thehouse door, as well as beside thelatrine. This creates a habit <strong>of</strong>hand-washing at important pointsin the day, such as after visitingthe latrine and before cookingand eating. It also means there issafe drinking water at any time. Latrine construction: Latrines can be builtfrom 100% local, cheap materials. Neighbourscan help each other build. <strong>The</strong> style will varydepending on the soil type and availability <strong>of</strong>straw, rocks and wood, but people should beadvised on the design to ensure their latrine issafely built. <strong>The</strong> other essentials are handwashing after each visit, and daily cleaning <strong>of</strong>the latrine so it is hygienic and pleasant, andpeople will actually use it. In addition to thehand-washing gourd or jerry can beside thelatrine, families can (1) make a cover for thehole when not in use (2) have a door that canalso be securely closed from inside (3) providea bin for used paper and a brush for cleaning. Refuse and compost pits: Training families todig pits in their compound for (1) waste vegetablematter (and ash) to decompose and become usefulfertiliser for gardening (2) refuse matter which can becovered over later, is a practical way to help peoplekeep compounds clean, and show that it is possible tostart a productive vegetable garden in a small space.91<strong>WaterAid</strong> in EthiopiaP.O.Box 4812, Addis AbabaTel: 251 114 661680Fax: 251 114 661679www.wateraidethiopia.org

Effective integration <strong>of</strong> water supply with sanitation and hygieneAs used in the ORDA-WAE Water, Sanitation and Hygiene programme, Achefer, Amhara.IN THE COMMUNITY Cattle troughs:<strong>The</strong>se were planned asmodels but have becomeintegrated in the project.Providing troughsprevents cattle fromdamaging water points.“Now even cattle have<strong>change</strong>d their behaviour.<strong>The</strong>y do not go for waterto the previous sources,but to the cattle trough.” Clean water: Realisingthe benefits <strong>of</strong> clean water,community memberswillingly contribute 0.12penny (2 birr) per month toa bank account to coverwater supply maintenancecosts. Students are able tohave clean drinking waterduring their school day withwater diverted from acommunity hand pump to areservoir close to the schoolwhenever the pump is notbeing used. In this waythere is no conflict betweenchildren and other users. Communityinitiatives:Overflow waterfrom waterschemes canprovideopportunities forcommunity treeplantations orcommunalvegetable plots.However the sameland is <strong>of</strong>ten usedfor cattle grazingand not everyonemay agree to anew use andtransparentdiscussions areessential. Sellingvegetables canprovide income tohelp maintainwater schemes. Clothes washing basins andshowers: Health promotion staffand teachers can encouragecommunity members to wear cleanclothes with competitions andrewards. In the Achefer project theschool director comments thatthere are no flies in school now thestudents come with clean facesand clothes and that they feel pridein their new behaviour.At first women were unwilling touse the communal showers, eventhough the walls <strong>of</strong>fered 100%privacy. It seems they wereculturally uncomfortable standingup to wash. Building a concreteseat for them to sit on and washhas made the showers popular. Raising funds and raising awareness: People from the nearby townvisit Achefer because their water is not clean and they do not haveclothes washing basins, showers and cattle troughs. <strong>The</strong> guard chargesfor each facility used and this helps cover maintenance and salary costs.Meanwhile more and more people understand the benefits andimportance <strong>of</strong> integrated WASH activities: that it is possible to preventabout 88% <strong>of</strong> diseases by practicing personal hygiene and sanitation.Organization for Rehabilitation and Development inAmhara2P.O.Box 132, Bahir DarTel: 058/2200985/ 0582201411Fax: 058220058710

Discussing.. hygiene, home improvements & horticultureDebasAdugna, (left),is an HP withthe Acheferproject. Debascomes fromYismala town.He has beenworking for theproject for ayear. Before heworked asKebeleChairman:“Personally I have a latrine and two handwashingfacilities - one attached to the latrineand the other at the main gate. So, I do notwait for my wife or others to give me water forhand-washing. I have also used ‘madaberia’to plaster the ro<strong>of</strong> inside my house and thewall is also kept very clean. We can washclothes twice a week. This has all beentaught to us by ORDA. We are also teachingthe same to others. In my neighbourhoodmany people <strong>change</strong>d when they saw whatmy wife is doing.My friends appreciate what I do but comparedto what I got previously, they say the paymentis too little. But I’m happy with what I do. Icome from this community and I would behappy to help them <strong>change</strong> practices. Myfuture plan is to see other villages also<strong>change</strong>d like Skut and Gudri. That they allhave good latrines, separate houses for theircattle, benefit from their garden, eat goodfoods that gives them resistance fromdifferent diseases - be rich like other areasand countries. That is my vision and I’m tryingmy best to realise this. For example, I oncehad to take people’s cabbages to Bahir Darto sell. <strong>The</strong> reason was they had planted a lotand it was not the fasting season so no onewas buying them. But I didn’t want people toget frustrated. From then on, I taught them tothink about the timing for the differentvegetables. We are also connecting villagerswith hotel owners so that they will havesomewhere to take their vegetables.Madaberia: plastic fertiliser sac or grain bag materialInjera: similar to pancake, the staple food in many areasI teach the community by going house-tohouse,or at the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony, about thebenefits <strong>of</strong> a latrine, hand-washing facilities,dry waste disposal pits, personal hygiene andso on. Also about house management – thatthey need to have a separate place forhuman and animals, and a place for cookingand sleeping. About energy saving stoves –for injera. We not only tell them about thebenefits but also show them how to makethem – that is, the latrine, the stove, shelvesfor household utensils. First we show them adrawing or a picture – both negative andpositive. <strong>The</strong>n we tell them the benefit <strong>of</strong> thepositive pictures. <strong>The</strong>n we show them how tomake it and how to use it – that way itbecomes simpler to communicate. <strong>The</strong> mainthing is whatever we show people is made <strong>of</strong>locally available materials. If they want toimprove it, it is going to be their decision, butwe make sure that they know they can makeit from local materials. We also use drama toteach people. We use students and theactive VHCs.”Sisay Berhanu (pictured front cover andpage 9 with water lifting device):“I have been doing well in gardening. So theproject gave me this pulley to encourage me.I’m happy. Not only because <strong>of</strong> the award butbecause the technology is introduced in thisvillage. <strong>The</strong>y also told us that it is possible todo it here. For example, my neighbour is nowplanning to make one for himself. Since wehave this one, we can copy it. <strong>The</strong> incentiveencouraged not only me but others as well. Ifyou work hard, you know that you will getsomething. Not always an award (fromORDA or government) but the fruits <strong>of</strong> yourlabour are also something. <strong>The</strong>se people aregiving us awards for the time and energy wespend to support ourselves. On the otherhand we should have given them awardssince they brought new ideas to our village.<strong>The</strong> technology, the new seeds that we didnot know before, and the lessons they gaveus, and the <strong>change</strong>s they brought to ourvillage. Our village is clean now. Everybodyhas a latrine and hand washing facility. Youdo not see even children’s faeces in anycompound. People are getting modernised.”11

Effective community sanitation and hygiene promotionAs used in the ORDA-WAE Water, Hygiene and Sanitation programme, Achefer, Amhara.PROMOTION METHODS Active community participation: Achefer communitymembers and woreda <strong>of</strong>ficials state that people becamemotivated to participate because <strong>of</strong> the practical stepstaken by the project (c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony, school club,incentives, house-to-house visits, horticulture, village-tovillageex<strong>change</strong> visits) – and that the project staff kepttheir promises. A woreda staff person says: “<strong>The</strong>y arepractical. <strong>The</strong>y taught us to be practical.” <strong>The</strong> projectcompound as a modelsite: <strong>The</strong> Achefercompound acts as aninspiring demonstrationsite with vegetables,water pulleys, a latrineand a shower.C<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony, television, and experience sharing : A budget for promotional resources forcommunity hygiene and sanitation related meetings can be money well spent. Creating regular c<strong>of</strong>feeceremony gatherings with music, films <strong>of</strong> experiences from other villages, award ceremonies using flagsand gardening tools, poetry readings - as well as trainings - has create a positive atmosphere in which tolearn and share information in Achefer. However, the film equipment (video camera, television, generator) iscostly, the issues can become repetitive, and people can become passive observers. <strong>The</strong> ceremony worksbest when it complements house-to-house visits - bringing people together and reinforcing learning. A committed promotion team: Good hygiene and sanitation promotion forthe present and the long term relies on a committed, communicative andcollaborative team that extends from the grassroots - Village HygieneCommunicators (VHC), water committees and water point guards - to paidpr<strong>of</strong>essionals such as Hygiene Promoters (HP) and Health Extension Workers(HEW), project staff, woreda water and health related staff and school teachers,and to the community administrators and <strong>of</strong>ficials such as members <strong>of</strong> kebelecommittees. <strong>The</strong> Project Coordinator’s role is key in setting effective managementand communications systems up but the individuals concerned will need their ownstrategy to ensure systems carry on after the project end. This is essential toensure the intensive house-to-house work <strong>of</strong> such people as HPs (right in thephoto) is not lost. What encouraged you tobuild a latrine?Community members inAchefer were asked to prioritise3 motivators out <strong>of</strong> 7 promotiontools. <strong>The</strong>ir responses were:Rank Motivator/Reason Point %1 House-to-house promotion 92 31.32 C<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony 73 24.83 Flag rewarding 39 13.34 Government enforcement 36 12.25 Influence <strong>of</strong> friends & neighbours 27 9.26 Video show 23 7.87 Fear <strong>of</strong> being publicly shamed 4 1.412Organization for Rehabilitation and Development inAmharaP.O.Box 132, Bahir DarTel: 058/2200985/ 058220141112

Looking to the future<strong>The</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> peopleAs a project Achefer has had many peopleinvest their expertise and time into making itwork over the last three years: the on-siteproject team, ORDA experts from Bahir Dar,support from <strong>WaterAid</strong> in Addis Ababa and10 Hygiene Promoters working with agrassroots team. <strong>The</strong> project has madeparticular efforts to link with woreda <strong>of</strong>ficialsand consciously brought all the differentindividuals together in regular meetings. Whathappens then when these staff people moveon, and Achefer is no longer a project, butsimply a community?A grassroots team<strong>The</strong> fact is – as with most WASH projects -the project has trained community membersover the three years who are now placed tocarry on - 67 VHCs, 155 individuals formingWASH committees, and 48 caretakers toguard and manage water points. But how dothey rate their own motivation and successfor the future when – with the exception <strong>of</strong> thecaretakers - maintaining the WASH activitiesis a voluntary commitment in addition to theirprivate work, rather than their paid job. Whatchallenges do they see and what are theirstrategies to overcome these?Members <strong>of</strong> the Gudri WASH Committee arepositive at present. <strong>The</strong>y witnessed thecommunity’s willing participation in the waterconstruction work and their continuingcommitment through contributions depositedto a bank account for ongoing maintenancework. Yaregal Mekonen who is committeemember, kebele chairman and a VHC says:“This water is for all <strong>of</strong> us. We work together.We know it is for the good <strong>of</strong> society.”Regarding sustainability the committee feelthey can use this account to maintain thepromotional and motivating mechanisms suchas the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremonies and the flagsystem. <strong>The</strong>y also have an idea for their owncommunity project: to fence <strong>of</strong>f land near thewater point and collectively grow vegetablesto raise more funds. However some in thegote are less keen on this idea, believing theland is more useful for grazing. Suchdilemmas might hint at possible challenges tocome. And while Gudri are aware that theirWASH committees in AcheferEach has 9 members and ORDA-WA expect agood gender balance. <strong>The</strong> members <strong>of</strong> thecommittee have the following responsibilities:• two VHCs (1 male, 1 female)• five WASH (3 male, 2 female)• two technicians (1 male, 1 female)People in Achefer say it is sometimes difficultto get women involved in community work.<strong>The</strong>y try hard but when it becomes impossiblethey choose men.<strong>The</strong> role <strong>of</strong> a WASH committee is to:• mobilise the community• make sure that the scheme continuesto work• make sure that the water is managedwell• report to the project <strong>of</strong>fice/woreda ifthere is a problem e.g. breakage• mobilise the community to contribute 1birr a month for the guards andmaintenancegote is one <strong>of</strong> the most dynamic in the projectarea, and other gotes have less selfconfidence,their positive feelings are basedin the trust that the woreda will support thecommunity after the project hand over: “At themoment we do not see any threat for thefuture. Up until now there has been noproblem. But if these come then we will reportthem to the Water Desk.”Government supportWoreda Administrator Goshu Endalamaw’sview <strong>of</strong> the situation is equally positive. Hesays his <strong>of</strong>fice sees the Achefer project as amodel, and they are inviting other kebeles inthe woreda to visit and learn from it. Whatmost impresses the woreda staff is thepractical approach to new technologies, thec<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony to which people can bringissues for discussion, and the sense <strong>of</strong>ownership that the community feels for theproject activities. In his view people’s mindshave <strong>change</strong>d so there is no going back. Areality however in terms <strong>of</strong> continuing thepromotion work is whether the woreda budgetis sufficient. He would like to replicate thec<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony in other kebeles andcontinue with the ORDA-WAE initiatedincentives, the woreda having already used13

small agricultural tools as awardssuccessfully for farmers at the zonal level.“We haven’t planned to use the c<strong>of</strong>feeceremony yet, but in the future the c<strong>of</strong>feeceremony can be an input for the HEW. Inthe agricultural activities <strong>of</strong> the woreda thereis what we call a Development Group. Wewant to integrate the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony withthat.” He said the Group are already adoptingthe practical approaches <strong>of</strong> the stove andlatrine in other kebeles.Goshu believes that ORDA have createdgood systems that - together with the allimportantsense <strong>of</strong> ownership – will endure.Individual water schemes have already beenhanded over to the community, thecommittees have been trained, and villagersare contributing money for maintenance. Hesees the woreda work as simply to helpsustain these systems and perhaps givesome refresher training, but that this is allwithin their capacity - that the government isplanning to upgrade the Water Desk to <strong>of</strong>ficelevel, while hygiene and sanitation is handledby the Health Desk.Health Extension WorkersIn the view <strong>of</strong> the HPs, as important asanything will be the way the governmentemployedHealth Extension Workers (HEW)work together with the community. Asrelatively new posts their remit covers some16 components - everything from nutrition toHIV, but amongst these are also sanitationand hygiene.Looking at some <strong>of</strong> the weaker gotes, someHPs are concerned sustainability might be aproblem. To try and minimise a possible dropin hygiene and sanitation progress andpractice, the HPs have been working closelywith the HEWs and passing names <strong>of</strong>households or villages that need follow-up tothem. <strong>The</strong> HPs are going house-to-houseonce or twice a week with the HEWs andhope the HEWs will continue such visits afterthe project ends. In the final months <strong>of</strong> theproject the HPs have started nominating elderand respected people who are listened to andrequesting that they keep discussing WASHissues with the wider communityManagement and regular follow upSome HPs fear, however, that despite theWomen users <strong>of</strong> the water point at Sununda Gote,Kualabaka. <strong>The</strong> Achefer project has worked toempower women by encouraging a gender balancein the WASH work. Women make up around 40%<strong>of</strong> WASH committees, and 80% <strong>of</strong> VHCs. Changingthe behaviour <strong>of</strong> women is essential for the futurehealth <strong>of</strong> the community. Rural Ethiopia’s traditionaldivision <strong>of</strong> labour means that it is women who areprimarily involved with fetching water, cooking,cleaning, washing clothes and child care.longer training (a year and a half) HEWsreceived, they lack the commitment the HPsfeel. A reason for this might be the way inwhich the HEWs have to cover so manyissues, or the fact that for the HPs the projectteam were able to motivate them through aclose and communicative management style.One HP commented: “We are pushing theHEWs to work with us as we’ll be handingover our responsibilities to them and we wantour work to be sustainable. But there needsto be a strict follow-up on the work they do ifthey want to bring <strong>change</strong>. In our case wehave allocated dates in a month formonitoring and evaluation. We criticise eachother and learn from one another. Every 12thday <strong>of</strong> the month I have a meeting with all theVHCs who work in the villages I work. Wehave a meeting to discuss reports from eachgote, to discuss challenges and listen tosolutions or suggest solutions. On the 29thday <strong>of</strong> the month, we have a meeting for allthe HPs and all the project VHCs together.”Whilst in most villages in the project arealatrines are being adopted quickly, the HPsare aware that it takes time for people toapply lessons on personal hygiene, andhence persistent follow up will be essential14

after the project has ended: “People are stillweak on shower and hand-washing habits.However, we are trying to follow that up aswell. We have developed a follow-up sheetand we know at least 5 people per day fromone gote are using the shower. We also tellpeople they have to come to the c<strong>of</strong>feeceremony clean, so that they can develop thehabit. We rely on the VHCs to help us onthis. Because they live in and are part <strong>of</strong> thecommunity, we use them to convince people.”Certainly the HEWs will need managementand motivation from their woreda managers ifthey are to continue this kind <strong>of</strong> follow upwork, but equally – when the HPs leave theproject – both the HEW and the woreda deskmanagers will need to work closely with theVHCs who are those staff who worked withinthe project and will remain after its end.Supporting staff who stay on<strong>The</strong> project team’s assessment <strong>of</strong> the VHCsis that some are stronger and some weaker.Clearly there can be many reasons forweakness, perhaps that they themselves arenot active or are less skilled communicators.But their progress can also be affected by theculture <strong>of</strong> the community they are workingwith, the management skill <strong>of</strong> the HP underwhom they work, the attitude <strong>of</strong> the WASHcommittee etc. At present the meetingsorganised by the wider project team supportthe VHCs but it will be important that thistrained human resource does not lose itsmomentum once the project ends.Village Hygiene Communicators (VHCs)• <strong>The</strong>re are two VHCs (male and femaledepending on selection) in each gote.VHCs report that women feel more at easewhen they are taught by female VHCs, andhusbands are <strong>of</strong>ten unhappy if a male VHCgoes to a house alone, thus VHCs <strong>of</strong>tenwork in m/f pairs or just female VHCs.• VHCs are selected by the community.• <strong>The</strong> project gave them 20 days training: 16days theory and 4 days practical.• <strong>The</strong>ir commitment is to work 10 days amonth for the community and 5 should beon usual working days.• <strong>The</strong>ir role includes educating people aboutpositive hygienic practices and mobilisingthe community.• <strong>The</strong>y commit to work after the project end.Respect at all levels<strong>The</strong> project successes are grounded inmutual respect between all staff and thecommunity. HPs say they generally havegood relationships with the kebeleadministration, <strong>of</strong>ten involving them inWASH committee activities. However in onecase kebele leaders used the c<strong>of</strong>feeceremony to agitate about tax, askingpeople to pay tax or be penalised. <strong>The</strong> HPshad to stop inviting the kebele leaders to theceremony, as people would feel suspicious<strong>of</strong> the purpose <strong>of</strong> an event whose focus wassupposedly WASH.On-going learningRefresher training is something that shouldkeep Achefer moving forwards. Some HPsquestion whether the five days training theyreceived via the project was adequate initself. In five days they learnt about hygiene,environmental cleanliness, about latrines andhow to construct them, about hand-washingfacilities and the simplest ways to make them.HPs were recruited because they hadmobilising experience, giving them theconfidence to stand up and teach people, butthe VHCs find this harder. In any case as thecommunity learns more their interest needs tobe held by new information. One HPcommented: “Now the farmers are changing.<strong>The</strong>re are 12th grade among them. We don’tknow if they come with challenging questionsand we cannot be seen as if we do not knowwhat we are doing. We need supportingmaterials and a budget for refresher training.”When to stop?In theory the HPs leave when the projectends. And usually an NGO will move on froma project area. However ORDA is to start anew similar project in a neighbouring area.At the time <strong>of</strong> the research visit the debatewas whether the HPs should stay on inAchefer for a further year. With the project’ssuccesses so great, but some gotes stillstruggling and neighbouring kebeles ready tolearn, could funding for continuingmanagement enable the HPs and HEWs toteam up and make a really significantdifference to WASH in the woreda. Deciding“when to stop” is possibly an important issuefor WASH colleagues to debate more.15

Looking to the futureMaintaining incentivesAn unusual sight greets one when visitingAchefer and that is the <strong>colour</strong>ed flags - somany households have one visible abovetheir ro<strong>of</strong>s. It is a sight suggesting activity andprogress relating to a project, but does it havean air <strong>of</strong> control or artificiality for normalcommunity life? Until now people have beenpositive – recognising the flags havemotivated <strong>change</strong>. Woreda staff admit theywere not initially convinced the idea was agood one, but the community assured them<strong>of</strong> the need for it. <strong>The</strong> flags have createdcompetition and there is an atmosphere <strong>of</strong>people wanting to be front line figures.However flags are part <strong>of</strong> a staff-intensivehygiene promotion system starting withhousehold visits and made effective throughpublic awards at the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony. Whilean evaluation in several years time canassess people’s <strong>change</strong>d hygienic practice,for the shorter term questions arise regardingthe sustainability <strong>of</strong> the promotion methods,e.g. can and will those staff members who willcontinue in Achefer (both paid and voluntary)maintain this level <strong>of</strong> intensity? And is anincentive system in fact necessary long-term?Project Coordinator Tesfaye Yalew ispragmatic about human nature andessentially positive: “After the project, the flagmay not continue. It is up to those who stayon. It was introduced to encourage those whodid not have a latrine. <strong>The</strong> upgradingmechanism was implemented to encouragesustainability. Our assumption is before weleave the project, we will be able to <strong>change</strong>people’s mind. Once they are <strong>change</strong>d, therewill not be any going back. I remember myfather throwing away fertilisers and notwanting cows to eat straw from the fertiliser. Itis about changing people’s minds. Nowfertiliser is used everywhere and the farmersknow the benefit <strong>of</strong> it. It is the same here: wejust need to show the benefits and people willcontinue to carry out sanitation and hygieneactivities. <strong>The</strong> promotion work we do isintensive so that people should not go backto their previous position.”While it may seem preferable to many tomaintain the flags and c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony forlonger until behaviour <strong>change</strong>s become afixed habit, there are also questions aroundthe sustainability <strong>of</strong> covering the cost <strong>of</strong> tools,sweets, and c<strong>of</strong>fee, as well as the eventualcost <strong>of</strong> replacing the TV equipment used inthe c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremonies as it wears out.Kualabaka school director, Getenet Abebe,stressed his wish to maintain the sense <strong>of</strong>competition between students in terms <strong>of</strong>being clean by introducing a new incentivesystem. Following the lead <strong>of</strong> the project staffwho visited to train the students, checkedtheir cleanliness and tested their knowledge,Getenet would like to award books and pensfor students at school with consistently cleanclothes and washed face. However theschool’s severe budget limitations mightmake this difficult to put into practice. <strong>The</strong>school’s role highlights the need for linkedpromotion between the generations. StudentYirdaw Amare states: “We have been tryingto teach our parents before about hygienefrom the things we learnt at school. But theydid not listen to us. We thank ORDA, now ourparents are listening to them and changingtheir behaviour. <strong>The</strong> reason they listen toORDA is because they come with water andthey also introduced this flag as an award.”Water and horticulture as incentivesWithout doubt water provision is a strongincentive for people and can be the catalystfor hygiene and sanitation activities, even if itis the intensive promotional work thatcements behaviour <strong>change</strong>s for life. With itshorticultural promotion work, tools and seedsawarded as incentives, Achefer also raisesthe issue that for many people food securitywill be a more immediate concern thanhygiene and sanitation. Can integratinghorticulture with WASH also be a way toengage people with the possibilities <strong>of</strong> theirown efforts to bring <strong>change</strong>? Meanwhile animportant consideration is the sustainability <strong>of</strong>water sources for gardening, as well as forwider WRM activities.“<strong>The</strong> gardening has also brought <strong>change</strong> in my and myfamily’s life. We sell beetroot for 0.12 penny (2 birr),cabbage 0.07 – 0.12 penny (1 to 2 birr), papaya for 0.18penny (3 birr). This is something we didn’t have before.For me I won’t have to worry about the children’suniform - I can use the money I got from the fruits. Thiscovers it all. My wife cooks good things with thecabbage, carrot, beetroot and potato. We are gettinghealthy foods as well.” - Sisay Berhanu, farmer.16

Looking to the futureHandover, “extra time”,planning and more..On several occasions during the short visit toAchefer it became apparent that although theproject design included a handover strategy,the process could be improved, both at theproject level and the community level. Thisobservation raises questions about transitionperiods in WASH work in general.Considering handover optionsClearly each situation has its unique qualities.For Achefer the project was the first one forORDA that strongly integrated sanitation andhygiene, providing them with a model for anew way <strong>of</strong> working. <strong>The</strong> HPs had only beenin place in Achefer for the final year <strong>of</strong> thethree-year project, and ORDA was staying onin the area. Because <strong>of</strong> new woredaadministrative divisions, half <strong>of</strong> the Acheferproject kebeles will fall into the new woredaORDA are moving on to. This gives thepotential for continued water, hygiene andsanitation work in the Achefer project kebelesand the chance to reach more households -given that a project is generally only able toprovide resources and promotion work tosome <strong>of</strong> the population <strong>of</strong> an area and rarelyall. If ORDA decides to continue working withthe HPs in the former Achefer project, or onlyin those areas that overlap with the newproject area, this has implications formanagement and the way in which HPs andHEWs can work together. Within this situationthere is also room for creative thinking aroundother ways <strong>of</strong> allocating staff, managing,carrying out ex<strong>change</strong>s and so on. Thinkingcreatively with the unique situation <strong>of</strong> eachproject as it phases out highlights the fact thatmore time might usefully be devoted tohandover in general: either in the planningstage, or at mid-term evaluation, or – verypractically - during the final project months.Extra time and equityConsidering ORDA’s new five-year projectarea <strong>of</strong> 10 kebeles (6 <strong>of</strong> which are formerAchefer project kebeles) draws attention tothe different attitudes present in the WASHsector. <strong>The</strong> original plan for Achefer was toachieve 39% water coverage. At the time <strong>of</strong>Going it alone? Is the transition from anorganised WASH project to communitymanagement too sudden because woredaWater or Health Desk responsibilities towardscommunities are not made clear enough afterproject staff leave? Can woreda and projectstaff establish a phase-out strategy jointly? InAchefer’s particular case this could mean oneyear <strong>of</strong> HPs working together with HEWs.the research visit the coverage was nearing40%. For the project staff the situation isfrustrating: ideally they would like to reach80% water coverage. Meanwhile in the finalmonths <strong>of</strong> the project, sanitation coveragevaries in Achefer’s project gotes, with somereaching 90-100% and others far behind.While WAE aims always to achieve 100%water coverage and 100% sanitation,ORDA’s view is regional, that there should bean equitable distribution <strong>of</strong> WASH investmentamong woredas, and they prefer to move to anew woreda, achieving some coverageeverywhere, rather than total coverage in justa few areas. ORDA sees their role asdemonstrating a model and the government’sobligation to fill the gap.Failing or weaker villagesWhile Achefer has shown itself to be broadlysuccessful, there are project gotes that areweaker in WASH or could be classified asfailing – where people are less receptive forany number <strong>of</strong> reasons – to do with culture,history, personality, isolation and so on, andother WAE reports have documented such17

instances in greater detail (e.g. A Tale <strong>of</strong> twovillages, available from WAE <strong>of</strong>fices). Shouldsuch villages therefore have more time spenton them before a project moves on? ProjectCoordinator Tesfaye Yalew’s view is: “It isgood to identify weaker and stronger villages.But if something is incurable then we don’tspend too much time and energy in thatkebele. We tried in Lihudi kebele again andagain but there was low participation andpeople were not positive about <strong>change</strong>. Tosome extent we then left and went to anothervillage and encouraged that village toparticipate and “not be like Lihudi”, i.e. weused negative villages for promotionpurposes. But if they <strong>change</strong> their mind wewill go and help them before we leave. In factone gote from there came to us and said wewill do whatever you want us to do. <strong>The</strong>y hadbecome convinced <strong>of</strong> the need for WASH.”Community plans for the futureOther issues community members raisedrelated to their visions for future work, suchas starting communal vegetable gardens orplantations around water points. One WASHcommittee is aiming to buy their owntelevision for kebele use from the sale <strong>of</strong>plants. This kind <strong>of</strong> development <strong>of</strong> WASHprojects is very possible - in an EOC-WAEproject in North Gondar one village hasbought their own generator for householdlighting - but people say they lack confidencein drawing up plans. Perhaps as part <strong>of</strong> theirhand over process NGOs should aim toprovide training in project planning?Meanwhile other community members voicedconcern that before ORDA left someoneshould be assigned to lead the WASH work –to help the c<strong>of</strong>fee ceremony, VHCs andWASH committees continue. Although suchan individual might not be deemedappropriate by either ORDA or WAE asworeda and kebele staff, WASH committees,VHCs and HEWs are all placed to ensureactivities continue the requests demonstratepeople’s perception that as the project endsthey are losing leadership that they would liketo continue in some shape or form. This mightsuggest a lack <strong>of</strong> clarity in the handoverprocess – that they are unsure who theyshould look to in any given situation. Equallyit could be a valid sense that someone shouldguide the community a little longer - toconsolidate successes and strengthenweaknesses.In briefQuestions from Achefer<strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> this report is to share learning. It isnot a project evaluation document includingproject recommendations etc. And as it ispublished some months after the researchtrip, neither does it aim to give an absolutelyup to date picture <strong>of</strong> the project andcommunity today. Instead it is hoped therange <strong>of</strong> ideas and processes emerging fromAchefer encourage interesting debateamongst WASH colleagues - and that thepull-out posters act as useful training tools.As with all learning, the visit to Achefer raisedas many questions as it presented answers,and just some <strong>of</strong> these are included here.Both ORDA and WAE would welcomefeedback on these or anything else raised bytheir reading <strong>The</strong> <strong>colour</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>change</strong>.• How should Water ResourceManagement options be brought intoWASH projects? What criteria do WAEand its partners have for WRM in differentprojects and regions? Should there be astandard strategy? Does it divert time andmoney from core WASH work or does itencourage? How is the sustainability <strong>of</strong>water resource measured?• To what extent is food security a centralconcern for people? Is tying vegetableproduction to sanitation appropriate?• How might the hygiene and sanitationmodel from Achefer be scaled up ordown, or modified depending on the size<strong>of</strong> project area, the permanent projectstaff and the partner organisationsworking together?• All WASH colleagues have experiencedvillagers who are uneasy about themotives and allegiances <strong>of</strong> NGOs. Forsome <strong>of</strong> the “failing” kebeles in Achefertheir unwillingness to participate stemmedfrom some discomfort around a perceivedpolitical agenda coming at the time <strong>of</strong>national elections. In what ways cancolleagues increase transparent debatearound these, and other, sensitive issuesthat might block effective WASH work?18

<strong>WaterAid</strong><strong>WaterAid</strong> in Ethiopia47-49 Durham Street Debrezeit RoadLondon P.O.Box 4812SE11 5JDAddis AbabaTel: 020 7793 4500 Tel: 251 114 661680Fax: 020 7793 4545 Fax: 251 114 661679www.wateraid.orgwww.Wateraidethiopia.org<strong>WaterAid</strong> – water for life<strong>The</strong> international NGO dedicated exclusively to the provision <strong>of</strong> safe domestic water, sanitation and hygieneeducation to the world’s poorest people.UK charity registration number 288701Date: August 2007<strong>The</strong> <strong>colour</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>change</strong> is dedicated to Tesfaye Yalew in acknowledgement <strong>of</strong> his vision and dedication as ProjectCoordinator with the Achefer project, and to the countless others who are spearheading the way in terms <strong>of</strong>hygiene and sanitation in Ethiopia. <strong>The</strong> research team would also like to express their thanks to all Achefercommunity members, project and woreda staff for their help in researching this report.