Writing Street View 4 Grade Spanish Unit 4 October 24 - Office of ...

Writing Street View 4 Grade Spanish Unit 4 October 24 - Office of ...

Writing Street View 4 Grade Spanish Unit 4 October 24 - Office of ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

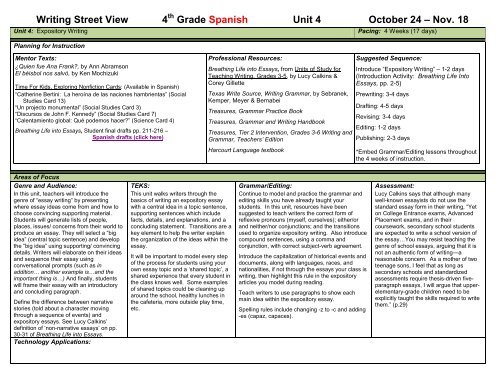

<strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Street</strong> <strong>View</strong> 4 th <strong>Grade</strong> <strong>Spanish</strong> <strong>Unit</strong> 4 <strong>October</strong> <strong>24</strong> – Nov. 18<strong>Unit</strong> 4: Expository <strong>Writing</strong>Pacing: 4 Weeks (17 days)Planning for InstructionMentor Texts:¿Quien fue Ana Frank?, by Ann AbramsonEl béisbol nos salvó, by Ken MochizukiTime For Kids, Exploring Nonfiction Cards: (Available in <strong>Spanish</strong>)“Catherine Bertini: La heroína de las naciones hambrientas” (SocialStudies Card 13)“Un projecto monumental” (Social Studies Card 3)“Discursos de John F. Kennedy” (Social Studies Card 7)“Calentamiento global: Qué podemos hacer?” (Science Card 4)Breathing Life into Essays, Student final drafts pp. 211-216 –<strong>Spanish</strong> drafts (click here)Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Resources:Breathing Life into Essays, from <strong>Unit</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Study forTeaching <strong>Writing</strong>, <strong>Grade</strong>s 3-5, by Lucy Calkins &Corey GilletteTexas Write Source, <strong>Writing</strong> Grammar, by Sebranek,Kemper, Meyer & BernabeiTreasures, Grammar Practice BookTreasures, Grammar and <strong>Writing</strong> HandbookTreasures, Tier 2 Intervention, <strong>Grade</strong>s 3-6 <strong>Writing</strong> andGrammar, Teachers’ EditionHarcourt Language textbookSuggested Sequence:Introduce “Expository <strong>Writing</strong>” – 1-2 days(Introduction Activity: Breathing Life IntoEssays, pp. 2-5)Prewriting: 3-4 daysDrafting: 4-5 daysRevising: 3-4 daysEditing: 1-2 daysPublishing: 2-3 days*Embed Grammar/Editing lessons throughoutthe 4 weeks <strong>of</strong> instruction.Areas <strong>of</strong> FocusGenre and Audience:In this unit, teachers will introduce thegenre <strong>of</strong> “essay writing” by presentingwhere essay ideas come from and how tochoose convincing supporting material.Students will generate lists <strong>of</strong> people,places, issues/ concerns from their world toproduce an essay. They will select a “bigidea” (central topic sentence) and developthe “big idea” using supporting/ convincingdetails. Writers will elaborate on their ideasand sequence their essay usingconversational prompts (such as inaddition… another example is…and theimportant thing is…) And finally, studentswill frame their essay with an introductoryand concluding paragraph.Define the difference between narrativestories (told about a character movingthrough a sequence <strong>of</strong> events) andexpository essays. See Lucy Calkins’definition <strong>of</strong> ‘non-narrative essays’ on pp.30-31 <strong>of</strong> Breathing Life into Essays.Technology Applications:TEKS:This unit walks writers through thebasics <strong>of</strong> writing an expository essaywith a central idea in a topic sentence,supporting sentences which includefacts, details, and explanations, and aconcluding statement. Transitions are akey element to help the writer explainthe organization <strong>of</strong> the ideas within theessay.It will be important to model every step<strong>of</strong> the process for students using yourown essay topic and a ‘shared topic’, ashared experience that every student inthe class knows well. Some examples<strong>of</strong> shared topics could be cleaning uparound the school, healthy lunches inthe cafeteria, more outside play time,etc.Grammar/Editing:Continue to model and practice the grammar andediting skills you have already taught yourstudents. In this unit, resources have beensuggested to teach writers the correct form <strong>of</strong>reflexive pronouns (myself, ourselves); either/orand neither/nor conjunctions; and the transitionsused to organize expository writing. Also introducecompound sentences, using a comma andconjunction, with correct subject-verb agreement.Introduce the capitalization <strong>of</strong> historical events anddocuments, along with languages, races, andnationalities, if not through the essays your class iswriting, then highlight this rule in the expositoryarticles you model during reading.Teach writers to use paragraphs to show eachmain idea within the expository essay.Spelling rules include changing -z to -c and adding-es (capaz, capaces).Assessment:Lucy Calkins says that although manywell-known essayists do not use thestandard essay form in their writing, “Yeton College Entrance exams, AdvancedPlacement exams, and in theircoursework, secondary school studentsare expected to write a school version <strong>of</strong>the essay…You may resist teaching thegenre <strong>of</strong> school essays, arguing that it isnot an authentic form <strong>of</strong> writing—areasonable concern. As a mother <strong>of</strong> twoteenage sons, I feel that as long assecondary schools and standardizedassessments require thesis-driven fiveparagraphessays, I will argue that upperelementary-gradechildren need to beexplicitly taught the skills required to writethem.” (p.29)

<strong>Writing</strong> Process: Expository <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Spanish</strong> Translations - page numbers correlate with Breathing Life Into Essays page numbersUnless otherwise noted, the lesson ideas below come from Breathing Life Into Essays, from <strong>Unit</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Study for Teaching <strong>Writing</strong>, <strong>Grade</strong>s 3-5, by Lucy Calkins & Corey GilletteBecause writers will need a lot <strong>of</strong> guidance, these lessons do not follow the typical workshop schedule <strong>of</strong> minilesson, independent writing / conferencing, and student sharing.Instead, you will work in brief cycles <strong>of</strong> demonstrating, having students practice orally, having students write and share, and return immediately to more demonstrating.Prewriting:Students will learn to live like essayists in this next unit <strong>of</strong> writing. “Students, instead <strong>of</strong>writing about small moments, we are going to write about big ideas. For this kind <strong>of</strong> writing,you are going to collect ideas from the world around you. You will think about things thatyou notice, believe in, and feel passionate about.”Essayists observe things they see, hear, read, and notice. Then they push themselves tohave ideas about what they observe by saying, “Esto hace que me dé cuenta de que. . .” o“La idea que esto me da es . . .” (pp. 2-5)Pg. 17, Example <strong>of</strong> Whole Class Model and Pre-write Strategy:Lo que yo notoDos niñas se sientan juntas, y muestransus almuerzos una a la otra.Lo que me hace pensarYo solía mostrar mi almuerzo. ¿Por quéson tan competitivos los niños? No esjusto para niños cuyos padres tienenmenos dinero. Ni para niños cuyas mamásno compran alimentos azucarados.Students should have many opportunities to pre-write from the class and student generatedlists. The purpose <strong>of</strong> the beginning mini-lessons is for students to respond to their ownissues/concerns, people, places, and passions.Prewriting Lessons: Strategies for Generating Essay EntriesLesson: Contrasting Narrative and Non-Narrative Structures, pp. 30-33Model telling a narrative story and a non-narrative using the same topic, p. 32Lesson: Mid-Workshop Teaching Point: Studying Essay Structures (Use the sample essayslisted in the mentor texts section <strong>of</strong> this <strong>Street</strong> <strong>View</strong> and the sample essay in Calkins, p. 36)Lesson: Model how to use prompts to help writers stay with an idea longer and pushthemselves to say more, pp. 46-49Lesson: Writers can generate ideas from the books they read, p. 63, Mid-WorkshopTeaching PointFinal Draft/Publishing:Publish essays and share them with anotherclass.Assemble student essays into an anthology todisplay in the library or near the visitor’s chairsin the school <strong>of</strong>fice.Post final drafts on a wiki page for invitedvisitors/parents to view.Students who are having trouble finding a thesisstatement in their entries: p. 81 – examples,We make thesis statements in our world to express ourfeelings and passions. Ex: Fútbol es mejor quebásquetbol. Tengo muchos quehaceres en la casa.Organizing: Teaching point for Comparing Genres: Expository Essays are organized byideas; Personal Narratives are organized by events. (See p. 30, par.1-3 for more details)Lesson: Developing a thesis statement and planning the direction <strong>of</strong> the essay, pp. 72-75Lesson: Boxes and Bullets: Plan the main sections <strong>of</strong> the essay by deciding how toelaborate the main idea. Design categories to match what the writer wants to say (reasons),pp. 84-88Lesson: Different ways to support a thesis: different kinds, parts, times, pp. 89-91, Mid-Workshop Teaching PointMore examples <strong>of</strong> thesis statements and supporting statements: p. 95Give students many opportunities for oral practice before drafting, p. 105, SharePractice using different kinds <strong>of</strong> evidence to support a thesis statement—kinds, parts,reasons, ways, and times, p. 106. (Do this as a whole class or have students work in smallgroups, rather than as a homework assignment.)Lesson: One way to organize, Collect stories in folders, pp. 110Lesson: Write a small story to support a claim, pp.112-113, Use a ‘shared story’ for studentsto practice with.Angling a story to illustrate the claim, pp.116-117, Mid-Workshop Teaching PointGuidelines for <strong>Writing</strong> Supporting Stories for Essays p. 120Children should naturally use transition phrases to show the relationship between theirideas: una razón, por ejemplo, yo también pienso que es importante que; también porque ,por otro lado, p. 123Lesson: Seeking outside sources (other people’s stories) and collecting quotes to support aclaim, pp. 128-129Lesson: Writers collect observations (and record what they see), interviews (to gatherquotes), and find statistics, pp. 162-165.Students can interview their friends, have friends interview them, and use an idea from abook they have read to support ideas, pp. 166-167, <strong>Writing</strong> and Conferring, and Mid-Workshop Teaching Point.Students should ask family members to help them gather information for their topic, p. 169,HomeworkConferencing:Drafting:Problems Writers Will Encounter / Calkins’Lesson: Making sure there is enough evidence to support all the claims,Conference SuggestionsQuestions to Ask <strong>of</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Before We Draft, Make sure the story supportsthe topic sentence, pp.172-173Lesson: Writers look through their folders, asking questions to determineif the story fits. Choices to make if a story does not fit (p. 175):Lesson: Students practice orally before writing. Have students practicetelling the ideas in one folder as if they are giving a lecture to a smallgroup, p. 178

A possible springboard lesson after sharing isto discuss how well the author proved theirpoint.Para ayudar a estudiantes a contar historias queapoyen la idea principal:• Lean de nuevo el párrafo, haciendo pausadespués de cada oración.• Pregunte: “¿Esto va con mi idea principal?”• 2 opciones: Hacer que convenga, O pasar deprisa, saltando detalles que no convengan.(pp. 154-155)Ways to create introductions, p. 197Ways to create conclusions, p. 198Use any <strong>of</strong> the revising lessons you have taught to thewhole class to reinforce these skills with a small group<strong>of</strong> struggling writers.Editing: Grammar/Editing TEKS can be taught during grammar mini-lessons using the followingresources. After each lesson, students should go to their Writer’s Notebooks or the current draftsthey are working on to find examples that can be added to the class chart. Encourage studentsto look for examples in their reading too, and publicly praise their ‘good eye’ for finding theseexamples by adding them to the class chart as well.“Spelling, Punctuation, and Grammar Toolkit” – An organizational tool for all these rules! TheGrammar/Editing TEKS listed below can be included in the “toolkit”. The Treasures practice pagescan be used as resources for the guided practice and/or independent practice activities.Capitalization: Tesoros Manual de gramática y escritura, pg. 176Fuente de escritura, pgs. 560Plural noun rules: Tesoros Manual de gramática y escritura, pg.170Fuente de escritura, pgs. 562Reflexive pronouns: Fuente de escritura, pg. 452Correlative Conjunctions: Fuente de escritura, pgs. 467, 634 – Students may not be able to findexamples already written into their drafts, but challenge them to produce an ‘y/e’ or ‘o/u’ exampleusing the ideas in their drafts.Teachers can also produce writing samples that contain sentences with spaces that need to befilled with the correct correlative conjunction and have students insert the correct form afterproviding them with a small “word bank” with several options.Compound Sentences and Subject-Verb Agreement: Fuente de escritura, p. 161Transitions: Fuente de escritura, pg. 146, 519-5204 th <strong>Grade</strong> Conventions Checklist – <strong>Spanish</strong>Lesson: Choose a logical way to order information, Model the thoughtprocess, using charts <strong>of</strong> support information collected, pp. 184-186Maneras de ordenar la información (p.186):• Orden cronológico• Las pruebas más firmes primero; dejar para el final un recuerdo claro.• Hacer categorías• Apoyar un lado, después el otro• De lo menos a lo más importante, usando palabras de transición.(p. 188 Mid-Workshop Teaching Point)Examples <strong>of</strong> transition words for chronological order, p. 189Example <strong>of</strong> the organization for two categories, along with transitionwords, p. 190Ways to create introductions, p. 197 and conclusions, p. 198Additional resource:Tesoros Manual de gramática y escritura, p. 130Revising:“Pushing our Thinking”, p. 49 – Use the prompts to help students stay with an idealonger and push themselves to say more. Do an example together as suggested on p.48, ‘Active Engagement’.Finding and Crafting Thesis Statements, p. 72-75 – Students look at previous seedideas from the personal narrative genre to look for seed ideas. Teacher will model howa writer thinks about an expository topic by asking questions: ¿Podría yo imaginarmeescribiendo un ensayo sobre esta idea? ¿Es esto lo que yo quiero decir?Revising strong central topic ideas, p. 98 – Writers should not wait until they are donewith a draft to begin revising their essay. Writers should carefully think about whatinformation they include to support their essay, and if it should be part <strong>of</strong> their finaldraft.Ways to order the information , p.184-188 – Use the information from one student to‘think aloud’ how to decide which organizational structure will work best for the thesis,supporting statements, and the type <strong>of</strong> evidence collected.Use the information from another student’s essay and have the class or a small grouphelp you determine the best organizational structure.Repeat this process <strong>of</strong>ten, so students begin to ‘hear the way an essay sounds’.Revising Introductions, p. 201, Mid-Workshop Teaching Point – This lesson is similarto writing different leads for a personal narrative. Students work with different wordsand phrases to write introductions.Additional resource: Fuente de escritura, pp. 487-489 – Providing support for a centraltopic with examples.Teacher Notes: Students’ first attempts at writing expository essays will not be perfect. Do not expect perfection! Remember that you are introducing this new type <strong>of</strong> writing and as theycontinue to hear and read examples from your modeling <strong>of</strong> your own writing, from mentor texts, and from their peers’ writings, they will begin to internalize the way an essay sounds. Youwill need to model, model, model, and keep giving your students opportunities to try again. Soon they will be experts!

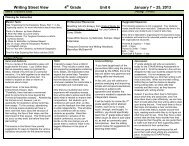

<strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Street</strong> <strong>View</strong> 4 th <strong>Grade</strong> <strong>Spanish</strong> <strong>Unit</strong> 5 November 17 – Nov. 22<strong>Unit</strong> 5: Revising BOY CompositionsPlanning for InstructionMentor Texts:Narrative:El pollo de los domingos, by Patricia PolaccoGracias, Sr. Falker, by Patricia PolaccoEcos del desierto, by Rene Almanza Silvia DubovoyExpository:Visit your school library to find <strong>Spanish</strong> expository texts appropriate for yourclass.“Good Dogs”,p.1, <strong>Writing</strong> Transparency, Macmillan/McGraw-Hill“It’s Time to Require Bike Helmets”,p.2 Wtg Transp, M/McGraw-Hill“Comida para todos”, Expository Essay, Fuente de escritura, p. 135-136Escribir un ensayo expositivo, Fuente de escritura, pp. 184-185Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Resources:This book was purchased for all pr<strong>of</strong>essionallibraries in AISD several years ago:Nonfiction Craft Lessons, By Ralph FletcherAISD has purchased this resource for all 2 nd –5 th grade classrooms. Teachers should see itsoon in either hardcover or electronic form:Texas Write Source, Houghton Mifflin HarcourtAnother pr<strong>of</strong>essional book found in manypr<strong>of</strong>essional libraries:Reviser’s Toolbox, by Barry LanePacing: 4 DaysSuggested Sequence:Revise Narrative BOY Compositions – 2 DaysRevise Expository BOY Compositions – 2 DaysNow that you have taught a complete unit for eachgenre, your students have a much betterunderstanding <strong>of</strong> what each composition shouldsound like and how they are different. You maydecide that your students need more work with onegenre or the other. Feel free to dedicate all 4 daysno one genre.Areas <strong>of</strong> FocusGenre and Audience:Review your anchor charts <strong>of</strong> the characteristicsfor each genre <strong>of</strong> writing before youbegin suggesting ways to revise thenarrative and the expository composition.You will need to continue to clearly definethe differences between the two types <strong>of</strong>writing, so students understand that theywill also need to revise in a different way foreach type <strong>of</strong> writing.When these BOY compositions were firstwritten, you probably did not discuss whothe audience was. Now is a good time totell your writers that when they write for atest, their audience is usually teachers orother adults who score their writing. Theyneed to know this for future test writing.Since you are revising these compositionstogether, you can now create a more realaudience for your students. Once theyhave turned these compositions into theirvery best writing, they become like newpieces <strong>of</strong> writing they can submit for awriting contest or share with any audience<strong>of</strong> students or adults.Technology Applications:TEKS:Students will revise their compositions during thisunit. Revising will mean different types <strong>of</strong> work fordifferent writers:• Some may need to focus their writing on only oneidea that is important to them.• Some may need to reorganize their piece to makeit flow more smoothly.• Some may need to develop their ideas better, byadding elaboration or stronger supportingsentences.• Others may need to delete unimportant details.• Others may need to use more sophisticatedvocabulary or to reword their sentences to use avariety <strong>of</strong> sentence structures.Now that your students have worked at length inboth genres, they will be able to advise each otherabout what is needed to improve their compositions.Set students up to conference with each, so theycan use the feedback from their peers to writeindependently and you can conference with as manystudents as possible. Read their compositions inadvance, so you can decide on the one change youwill advise them to make to result in the biggestdifference in this piece <strong>of</strong> writing.Grammar/Editing:No new grammar and editing skillsare taught during this unit. Reviewall skills taught in previous units.Assessment:Although not much is known about theSTAAR assessment, we do know thatthe ‘Revising and Editing’ portion <strong>of</strong> thetest will look more like a writingconference and students will be askedthe types <strong>of</strong> questions real writers workto solve during a writing conference.Therefore, the revising process needsto be explicitly taught to students. It canbe modeled with the whole group, usinga student’s writing that needsimprovement. However, it will also bebeneficial for the teacher to hold smallgroup conferences, where the groupworks together to suggestimprovements for the writing.Writers need to be aware <strong>of</strong> the placesin a story or essay where meaningbecomes unclear, or where a betterlead or a snapshot, a better supportingsentence or concluding paragraph, willmake the writing more effective.

<strong>Writing</strong> Process: Revising BOY CompositionsAPrewriting:Both genres: Read aloud one <strong>of</strong> the mentor texts shown on the first page <strong>of</strong> this<strong>Street</strong> <strong>View</strong>. Point out how the author focused his/her writing on one specifictopic, and then organized it in a way that made sense. Reread the lead, thesentences that create a vivid picture in your mind or a clear explanation <strong>of</strong> theidea. Write some <strong>of</strong> the interesting vocabulary or a few sentences that stand outto you on a chart for students to reference. Explain why you like the sentencesyou chose. Read to create a rhythm or flow to the writing and tell students thattheir writing should have that same feeling <strong>of</strong> rhythm and flow. It’s a smoothnessthat we find in a well-written piece <strong>of</strong> writing, that leaves us feeling satisfied at theend, leaves us thinking and motivated to tell someone else about the writing.Expository: A Group Activity for Refining the Thesis and Topic Sentences,p.3Final Draft/Publishing:Both genres: After writing the final draft, have studentsfill out this Reflecting on Your <strong>Writing</strong> page to keep withthe final draft. (Texas Write Source, p. 112 and p. 172)Reflection – Personal Narrative, p.17Reflection – Expository, p.18Students might display their ‘before’ and ‘after’ versions<strong>of</strong> their writings with an explanation <strong>of</strong> the changes theymade and their statement that explains: The main thing Ilearned about writing a personal narrative (or expositoryessay) is. . .All Attachments for this unit can be found here.Organizing:Narrative: Focus on the Big Moment, p.4 - This lesson will help students determine themost important part <strong>of</strong> their writing and zoom in to write with detail about that one importantmoment in their story.Expository: Using your own essay (or a student’s essay from the expository unit you justtaught), create poster-sized examples illustrating an essay organized in a few different ways:chronological order; strongest evidence first; least to most important; and support one sidethen another. Highlight the transition words used to signal the reader about how theinformation is organized. Ask writers to try organizing their topic in one or more <strong>of</strong> theseways and to label their paragraphs to show the organizational structure, the way you have onyour posters.Expository: Now that writers know many different ways to support their topic sentences, givethem time before drafting to generate more: small stories to support a claim; other people’sstories; collecting quotes; observations; interviews; statistics; ideas from books they haveread.Conferencing:Narrative: Students use this Narrative Checklist,p.12 to give feedback on their own and each other’spersonal narratives.Expository: Writers use this Expository Checklist,p.13 to give feedback on each other’s expositoryessays.Editing:Both genres: Research to Find the Correct Spelling, p.14: We should not expect writersto spell every word correctly in every draft. However, we do want them to think about thespelling <strong>of</strong> their words. Only when they become aware <strong>of</strong> the words they may have troublewith, will they slow down to try different solutions to their ‘problem words’.Both genres: Sentence Boundaries, p.15: Have writers ‘frame’ each sentence <strong>of</strong> theirwriting to think about whether it is a complete sentence.Both genres: Read your students’ compositionsahead <strong>of</strong> time, so you can decide on the one changeyou will advise them to make that will make thebiggest difference in this piece <strong>of</strong> writing.Drafting:Narrative: S.I.P. Chart for Developing Ideas, p.19 – Agraphic organizer to help students use ‘feelings’ and‘thoughts or speaking’ to develop the main parts <strong>of</strong> theirstory.Both genres: Instead <strong>of</strong> drafting the entire story or essaybefore getting any feedback on the writing, would it helpwriters to write only one part <strong>of</strong> their story or essay and aska partner for feedback before proceeding on to the nextpart? Allow writers to determine when to stop to ask forfeedback. The only rules are that every time they ask a peerfor feedback, they must read their piece from the verybeginning. And they must truly be open to the feedback theyreceive. (‘Why ask so many people for their opinions ifyou’re not going to make any changes, right?’)Revising: Both genres: Show Writers How to Add and Move Text, p.5Narrative: Transitions Establishing the Passage <strong>of</strong> Time, p.6Both genres: Revision Strategy: Rewrites, p.7-8 Although the example in thisattachment is written for a narrative writing, it can just as easily be adapted for expositorywriting.Expository: <strong>Writing</strong> in Paragraph Form, p.9-11Both genres: Editing Checklist, p. 16Evaluar una narración, Fuente de escritura, pp. 106-111Evaluar un ensayo expositivo, Fuente de escritura, pp. 166-171Teacher Notes: Lucy Calkins advises: “Practice finding something to celebrate [in students’ writing], even in the writing that doesn’t at first impress you. When children are new atsomething, it may not be immediately obvious what you want to celebrate, so look closely. In conferences, mid-workshop teaching points, and shares, you need to be able to name whatone child has done that you hope they repeat and others emulate.” (p. 42)

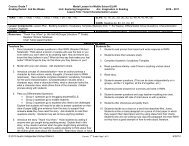

<strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Street</strong> <strong>View</strong> 4 th <strong>Grade</strong> <strong>Spanish</strong> <strong>Unit</strong> 6 December 5 – Dec. 20<strong>Unit</strong> 6: Response to Expository <strong>Writing</strong>/ Letter-writingPlanning for Instruction:Mentor Texts:• El león que no sabía escribir by Martin Batscheit• Querida Sra. LaRue : cartas desde la AcademiaCanina by Mark Teague• Ateutamente, Ricitos de Oro by Alma Flor Ada• Querido Pedrin by Alma Flor Ada• Clic, clac, muu : vacas escritoras by Doreen Cronin• Querido Señor Henshaw by Beverly Cleary (oneor two chapters)• Con mi hermano by Eileen RoePr<strong>of</strong>essional Resources:• A Genre Study <strong>of</strong> Letters• Who's Got Mail?• Write Letters That Make Things Happen (This is a greatconnection to Social Studies/ Citizenship)• Letter Writer Helper (with Arthur)• Dear Librarian:<strong>Writing</strong> a Persuasive Letter• Letter <strong>Writing</strong> Tips and Ideas• <strong>Writing</strong> LettersCheck your school’s library for these pr<strong>of</strong>essional books:• <strong>Writing</strong> About Reading, Janet Angelillo (Ch. 7)• Thinking Through Genre, Heather Lattimer (Ch. 7)• Guiding Readers and Writers, Fountas and Pinnell (Ch. 17-Responding to Literature; Pgs. 295-296- Questions forComprehending Pgs.152-156-Respond with Letters)• Strategies That Work: Teaching Comprehension forUnderstanding and Engagement, by Stephanie Harvey andAnne GoudvisOther detailed lessons for Response to Literature:Letter to an Author, pp.1-7Pacing: 12 daysSuggested Sequence:Expository: 10 days• Read and Discuss Expository <strong>Writing</strong> andText Features: 1-2 days• Responding to Expository <strong>Writing</strong>: 9-10days “Responding to a Textbook” (WriteSource pgs. 276-279)<strong>Writing</strong> a Personal Letter: 2 daysDifferentiation: As you work through this process, itis important to scaffold the learning for strugglingstudents. One way is to pair them with academicallyadvanced students as they work through this finalpiece <strong>of</strong> the revision and editing process. Theirdiscussions can help the students to apply theseskills and begin to truly master them.Areas <strong>of</strong> FocusGenre and Audience:As the students begin todiscuss the variousnonfiction texts, focusmuch <strong>of</strong> the discussion onthe following “essentialquestion…”• How is expositorywriting different from,and the same as,narrative writing?TEKS:It is important for students to understand how thesetwo genres differ from the more familiar narrativeformats.The rules for punctuation and form for a letter arequite different from typical text. Be sure to providenumerous models and opportunities for practice.These two pieces provide opportunities for studentsto practice being very specific and concise in theirwriting (a skill that will be vital for success on theSTAAR).Grammar/Editing:The primary grammar focusfor this unit should beplaced upon the format <strong>of</strong>letters, both formal andinformal.This is a great opportunityfor a review <strong>of</strong> highfrequencywords from thefirst semester. Havestudents be sure thesewords are spelled correctly.Assessment:Persuasive Letter RubricFriendly and Business Letter RubricsAs this is the end <strong>of</strong> the first semester, this is a great opportunity forstudents to assess their own writing using a rubric. Use the rubricsabove, along with what your class has focused on, to create a kidfriendlyrubric. It should focus on what you hope to see (not what youdon’t want to see), and include specific criteria for each score/pointlevel. Sample Starter Rubric is one way you can start your own rubric.Technology Applications: Letter Generator provides an online template for writing a letter; During this two-and-a-half week unit, students can also learn the basics <strong>of</strong> email throughLearning.com lessons (Sending Email Messages, Email the President, Responding to Email Messages, Review, Email Basics Quiz). Technology Integration: TEKS 1B, 2B, 2D

<strong>Writing</strong> Process: Editing/ Publishing/ Demonstrating Independent <strong>Writing</strong>Prewriting:Response: Use the essential question, ““¿Cómo pueden ayudar los texto expositivos a losescritores que escriben sus propios textos expositivos?” to focus the initial discussion.Using the Social Studies text [Harcourt Horizon], select a topic being studied and work throughprewriting a letter to the publisher. One possible sequence is suggested in Write Source (pp.276-277). Now, introduce the types <strong>of</strong> letters and discuss the similarities, differences, andaudiences for each. A Genre Study <strong>of</strong> Letters (sessions 1-3) is a great resource. (Other booksfrom the list can replace The Jolly Postman if needed.) As you work through the prewritingphase, have students strongly consider their audience, emphasizing that this will be a businessletter.Final Draft/Publishing:Responses: Students type a final draft <strong>of</strong> their response letters. It they wroteabout library books, share them with the librarian and/or other teachers tomotivate other students to read the books.Letters: Students write/ type their final drafts, address envelopes and sendletters to the textbook publisher.HOLIDAY CONNECTION: As this is the last unit prior to the winter holiday, itis a great opportunity for students to use the last two days <strong>of</strong> the semesterand apply the letter writing work to a “gift” for a special family member orfriend. Read Con mi hermano, by Eileen Roe, to the class. Have them thinkabout people (like the boy’s brother) who are special to them. As they workthrough the letter-writing process, have them write a letter to one specialperson, highlighting how/why that person is so special to them.Editing:As you work through the editing process, it is important to discuss the essential question, “¿Porqué son importantes los estándares para la escritura del idioma Español?”Capitalization and Punctuation: Create an anchor chart for specific capitalization and punctuationrules for a letter (to guide students through editing their letters).Spelling: Discuss the spelling words on the commonly used word list Non-negotiable Word List.Lead a discussion about how some words can confuse writers, and brainstorm strategies forstudents to check their spelling as they edit what they are writing (dictionary, spelling dictionary,www.dictionary.com , peer with strong spelling skills…).As they peer-edit, be sure that all students are involved in this part <strong>of</strong> the learning process as itserves more than one purpose. It not only helps them polish their writing for publication, butprovides a platform for making meaning <strong>of</strong> the lessons/concepts within the context <strong>of</strong> their ownwriting.Conferencing:Peer sharing groups providepowerful feedback for movingtheir writing forward.This is a good opportunity foryou to spend more time withstruggling writers (addressingtheir needs with more depth),while others benefit primarilyfrom peer conferences.Drafting:Response: Students consider their message about the text, as well as the more formalaudience as they develop a first draft. (Write Source pg. 278 might help guide you) As Sswrite, remind them that all their sentences need to be relevant to their message to thepublisher. They also need to be sure to include suggestions for the publisher to consider.Letters: Develop an anchor chart identifying the components and organization/ form <strong>of</strong> aletter. Who's Got Mail? provides a good sequence <strong>of</strong> lessons for this, but you can easilyhave students explore mentor texts and identify these components. Students draft aletter about the text they have selected.• Letter Writer Helper (with Arthur) is a good tool to support struggling students intheir first letter-writing experiences.Organizing:Response: Ss work in small groups to get feedback on theorganization <strong>of</strong> their drafts. Listeners focus on:• ¿Explico el escritor de la carta la razón por la que decidióenfocarse en este texto?• ¿Muestra esta carta una comprensión del texto?• ¿Sugirió el escritor una idea clara para mejorar el texto?Letters: Ss work in small groups to get feedback on theorganization <strong>of</strong> their drafts. Listeners focus on:• ¿Contiene la carta saludo, cuerpo, y despedida?• ¿Explicó el escritor su tema/mensaje de manera clara?• Si hubieras recibido esta carta, ¿te sentirías motivado aresponder en base a su conclusión?Revising:As they begin to revise, have them strongly consider the essential question,“¿Por qué la escritura de cartas es aún una destreza importante para que lapractiquen los escritores de hoy?”This discussion should also include how email is similar and different fromtraditional paper letters.Response: See “Organizing.”While it is most valuable to create a working criteria chart and rubric with yourstudents, the checklist on pg. 279, <strong>of</strong> Write Source is a good starting point. They alsoneed to be sure their writing is more formal, with the “publisher-as-audience” in mind.Letters: Students consider the peer feedback and revise their letters accordingly.They need to keep in mind that they have the final word on how to communicatetheir message (and avoid making a change just because a peer suggested it.)Teacher Notes: It is important to note that the writing process is recursive, and the stages do not always flow in the same order. Sometimes they occur simultaneously, and the writer<strong>of</strong>ten goes back and forth between the stages.