A Private Lands Conservation Success Story - Natural Resources ...

A Private Lands Conservation Success Story - Natural Resources ...

A Private Lands Conservation Success Story - Natural Resources ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Restoring America’s Wetlands:A <strong>Private</strong> <strong>Lands</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong><strong>Success</strong> <strong>Story</strong>yWetlands Reserve ProgramHelping People Help the Land

4Science-BasedAssistance and<strong>Lands</strong>cape-Scale<strong>Conservation</strong>NRCS technical specialists workcooperatively with landowners, anduse the latest wetland restorationscience to maximize wetland andwildlife benefits. NRCS specialistscollaborate with federal and statewildlife agencies, researchers anduniversities, conservation districts,and nongovernmental organizationsto develop and implement the mosteffective hydrologic and vegetativerestoration, and managementtechniques.WRP funds helped restore wetland habitat in a Michigan Audubon Societysanctuary, famous for thousands of Sandhill cranes who visit during their migrationand for Massasauga rattlesnake habitat, a state Species of Concern. Partners includedDucks Unlimited, Michigan and Jackson Audubon Societies, Michigan Department of<strong>Natural</strong> <strong>Resources</strong> and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.NRCS strives for a diversity of nativeplant and animal communities throughrestoration and management ofwetland hydrology and vegetation.Restored WRP projects provide avariety of water depths and habitattypes for wetland-dependent wildlife,including birds, amphibians, reptilesand mammals.The voluntary nature of WRP allowseffective integration of wetlandrestoration on working landscapes,providing benefits to farmers andranchers who enroll in the program,as well as benefits to the local andrural communities where thewetlands exist.Over the last 20 years, WRP hascatalyzed true landscape-scaleconservation. Individual WRPeasements, which can range fromtwo to 26,000 acres, are oftenadjacent to other WRP easements,or protected areas such as refugesand parks. The linking of theseprojects has resulted in the creationof significant wetland and wildlifecorridors.Waterfowl rise up out of a WRP project in south central Kansas.

5Water QualityHealthy wetlands serve as the“kidneys” of our landscape.Wetlands decrease soil erosion andfilter out sediments, chemicals andnutrients by capturing and slowingwater. Research shows that manywetlands can trap at least 50 percentof dissolved phosphate and 70 percentof dissolved nitrates running off nearbylands before they enter our Nation’swaterways, and ground and surfacewater supplies.Studies from the Prairie PotholeRegion in North Dakota, SouthDakota and Minnesota show thatWRP projects in these states havethe potential to reduce soil loss byas much as 124,000 tons per year.That’s enough soil to fill over 3,600dump trucks. The amount of soil couldprevent over 400 tons of nitrogen and5.5 tons of phosphorus from washingdownstream in the area alone.(Tangen 2008)“The goals of the Wetlands Reserve Program met our goals perfectly. We wanted tocreate the best wetland out there, and the Wetlands Reserve Program provided us thetechnical and financial assistance to make that happen.”—Don Cox, Nebraska,with 387 acres of WRP permanent easements.Improving Water Quality in Florida’sEvergladesFive properties of over 26,000 acresowned by four landowners alongFisheating Creek in the NorthernEverglades Watershed have createdone of the largest WRP easementareas in the Nation. FisheatingCreek is one of the last free-flowingwaterways entering Lake Okechobee,a favored recreational spot andan area with an impact on waterquality and quantity concerns in theEverglades. This landscape alsosupports 19 Federally Endangeredand Threatened species, including thered-cockaded woodpecker, wood storkand Florida panther.Over 26,000 acres of seasonal andforested wetland habitat was protectedas part of the Fisheating Creek WRPproject in Florida.WRP wetland habitat is helping witherosion control in the Prairie Potholeregion of North Dakota in addition toproviding critical waterfowl breeding andnesting habitat.page 5

6Flood PreventionWRP wetlands can help reduce downstream flooding and lessen damagingimpacts from floods. Wetlands provide a safe area not occupied by homes orfarms to spread, slow and store floodwaters. A one-acre wetland typically storesabout three-acre feet of water, or one million gallons. Trees and other wetlandvegetation also slow flood waters. This action, combined with water storage, canlower flood heights and reduce the water’s destructive potential. Wetlands alsoallow water to be absorbed into the soil providing groundwater recharge andmore moderate stream and river flows over longer periods of time.(Source: EPA)Wetlands can help slow and store floodwatersfrom nearby streams and rivers.Minimizing Flooding in the Red River ValleySignificant flooding has occurred in Minnesota’s Red River Valley over the lastfew years, causing damage to cropland and infrastructure. WRP projects arehelping slow and store floodwaters. Research shows restored WRP wetlands inthe Prairie Pothole Region have a water storage capacity of over 23,000 acrefeet—thiswould cover 46,000 acres, or an area the size of Washington D.C., insix inches of water. (Gleason 2008)

7Fish & Wildlife HabitatWRP provides habitat for a widediversity of plants and animals thatdepend upon wetlands, and wetlandassociatedforests and grasslands.One-half of all bird species in NorthAmerica and more than one third of allfederally listed species depend uponwetlands during part of their lifecycle.Habitat loss and fragmentation hascaused the decline of many species,and habitat restoration is neededfor many of these species to returnto viable populations. WRP projectsare providing critical habitat for, andaiding in the recovery of, a wide rangeof these rare and declining species,including wood storks, whoopingcranes, Indiana bats and bog turtles.Landowner Palmer Traynham (right) with NRCS biologist Tim Hermansen, California.“I see the Canada geese nesting here, thewood ducks and all the shorebirds. WhenI was a boy, you never saw them aroundhere.”—Palmer Traynham, California,who manages 340 acres in WRPpermanent easement.Improving Wood Stork PopulationsCurrently listed as a federallyEndangered species, wood storks nestin colonies or rookeries in cypressswamps. During the 1970s, when thepopulation was at its lowest, the storksprimarily nested near the FloridaEverglades. In 2010, a colony of over125 wood stork nests, 580 cattleegrets and various other waterbirdswere discovered on a WRP projectin southwest Georgia. Since thesesouthern restored wetlands are sovaluable to these birds, WRP isconsidered essential to the federalWood Stork Recovery Action Plan.page 7

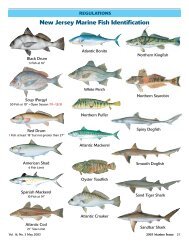

8Restoring <strong>Natural</strong> Tidal FlowsWRP is considered a ‘Lifeline forFisheries.’ For example, GooseneckCove in Rhode Island is now restoredafter decades of degradation.Restoration brought back the naturaltidal flow in the marsh, along withnative vegetation, and improvedhabitat for striped bass, bluefish andnumerous water birds.More Louisiana Black BearsDue to habitat loss, the Louisianablack bear’s population was severelydiminished to roughly 100 bears by the1950s in Louisiana. Listed as federallyThreatened in 1992, WRP helpedreverse the bear’s decline, with thefirst documented litter found on a WRPeasement in 2004. With continuedutilization of WRP habitat, the bear’spopulation in Louisiana, Arkansas,Mississippi and Georgia is nowestimated at 500 bears and growingsteadily.WRP Creating Swan HabitatTrumpeter swans, one of the largestnative North American birds, wereextinct in most of the U.S. by theearly 1900s and are now making acomeback. In fact, trumpeter swanssuccessfully nested on a WRP wetlandsite in Appanoose County, Iowa—the first time in this location for over100 years.

9Restoring Habitat for WhoopingCranesThe federally Endangered whoopingcrane is dependent upon wetlandhabitat. Once found throughoutthe Midwest, the results of habitatloss and hunting diminished thepopulation to only 21 cranes by 1941.<strong>Conservation</strong> efforts including WRPhave played a critical role in thesurvival of the whooping crane. Thereare now over 400 whooping cranes,some of which have been documentedusing WRP wetlands in Wisconsin,Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Texas, andFlorida.page 9

10Providing Waterfowl Habitat in theRainwater BasinHistorically, over 200,000 acres ofwetlands existed in Nebraska’s 21counties making up the RainwaterBasin (RWB). While only 17 percentof those wetlands remain, millionsof migrating waterfowl in the CentralFlyway still stop there each year. Todate, WRP has restored over 5,000acres of wetlands in the RWB. WRPwetlands provide over 12 percent ofthe much-needed, wetland-derivedfood for migrating waterfowl whilethey are in the RWB. (CEAP study,2008) In addition, the U.S. Fish andWildlife Service estimates that WRPwetlands in the neighboring PrairiePothole Region of the Dakotas have apotential waterfowl carrying capacity ofover 48,000 pairs of ducks per year.Mitigating <strong>Natural</strong> and Man-MadeDisastersNRCS established the Migratory BirdHabitat Initiative (MBHI) to increasehabitat for migratory birds impactedby the Deepwater Horizon/BP oilspill. As part of this, NRCS specialistscollaborated with private landownersand conservation partners to boostopen water and available food forthe migrating birds. WRP projectsmade up a significant portion of thenearly 500,000 acres NRCS enrolledin MBHI, providing more habitat forthe over 50 million birds that migratethe Mississippi, Central, and Atlanticflyways each year.

11Recovering At-Risk SpeciesWRP habitat can help prevent thelisting, and accelerate the recovery, ofat-risk species. A collaborative effort inOregon’s Willamette River Watershedwhere 62 landowners enrolled 7,600acres into WRP improved Oregonchub survival. The habitat restorationand subsequent population increasehelped the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Servicedecide to down-list the chub fromEndangered to Threatened. Otherspecies also benefitted, such as theUpper Willamette Spring Chinooksalmon, Fender’s blue butterfly andNelson’s checkermallow.Habitat for the Bog TurtleWRP is providing habitat for the bogturtle in eastern states with specificfocus in Pennsylvania. This small,semi-aquatic turtle has been listedas a federally Threatened speciessince 1997.Restoring Forested WetlandsThe Mississippi Alluvial Valley is theNation’s largest floodplain and acritical region for numerous species ofwaterfowl, including wintering mallardsand wood ducks. However, the regionhad lost 75 percent of its historicalforested ecosystem by the 1970s.WRP work has restored over 530,000acres in the floodplain. On WRPeasements in the valley alone, enoughforaging habitat now exists for 136,000ducks for 100 days. (King et. al. 2006)page 11

12“[The] wildlife gives us hours of enjoyment.And as a hunter, I want to enhance theland, where it can benefit everybody. Thebenefits will last long after I’m gone andmy grandkids will have something to lookforward to.”—John Walker, Delaware landowner,with an 8-acre 30-year WRP easement.Recreation & EducationA growing human population has a greater need for recreation, opportunitiesto enjoy natural settings, enhance health and wellness, and connect withfamily and friends. Wetlands can serve as outdoor classrooms whereecological principles and appreciation for natural and cultural resources canbe taught. Many WRP wetlands provide recreational bird-watching and huntingopportunities for landowners.Inspiring Community InvolvementIn Indiana, a BioBlitz was held at the Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area WRPwith teams of scientists and community volunteers scouring the site to tallyspecies of birds, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, insects and plants. After atwo-day search, the teams recorded over 1,000 species on the property.

13WRP wetlands can offer their landowners a variety of recreational opportunities.Outdoor classroom in Montana’s SilverSprings WRP.Potawatomi Tribe WRP project.Outdoor Education PossibilitiesWith landowner cooperation, manyrestored WRP sites provide outdoorclassrooms for local schoolchildren.Here, schoolchildren from theSheridan High School explore theSilver Springs WRP in southwesternMontana.Restoring Tribal <strong>Lands</strong>In Indiana, the Pokagon Band of thePotawatomi Tribe has utilized WRP torestore over 1,100 acres of their nativeland back to historic marsh conditions.The project included re-establishingtraditional wild rice beds historicallyimportant to their members.page 13

15More Benefits to ComeWRP wetlands provide long-termbenefits on a landscape-scale—tohelp heal lands after natural disasters,provide critical habitat for a long list ofwildlife species, filter out toxins fromour drinking water and much more.The cumulative benefits of WRP alsoimprove the vitality of agriculturallands, and the aesthetics andeconomies of local communities.Restoring and protecting our Nation’swetland resources in a thoughtful waythat maximizes the benefits for all whodepend on them will take substantialand continued effort, and require longtermengagement of private citizensand conservation agencies andorganizations. WRP offers a highlysuccessful model for the way forward.WRP has become the preeminentfederal private lands program forprotecting and restoring wetlands—itis a true conservation successstory. Several U.S. Presidents havementioned WRP as a critical wetlandrestoration program, and WRP nowprovides a foundation for otherprograms and landscape-scale plansconducted by state, federal andnongovernmental organizations.The Boundary Creek WRP in northern Idaho provides habitat for the white sturgeon,caribou and grizzly bear. Photo by Idaho Department of Fish & Game.The key to WRP’s success is itsinvolvement and enthusiasm fromprivate landowners and NRCSconservation partners. Landownersacross the country have watchedwetland habitat positively transformtheir land and, their community. Thereare thousands of acres still on theenrollment waiting list. WRP hasproven to be a program where NRCS,landowners and many various partnerscan work together to achieve trulycooperative conservation resultingin long-term benefits on a landscapescale that will ensure our wetlandresources are available for futuregenerations.A 211-acre WRP easement in theMississippi River Drainage area ofwestern Kentucky is only a half-mile fromthe Reelfoot National Wildlife Refuge.Remnant of a cypress/tupelo wetlandin central Mississippi as part of aWRP easement.page 15