Download this article (PDF) - University of Pennsylvania

Download this article (PDF) - University of Pennsylvania

Download this article (PDF) - University of Pennsylvania

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

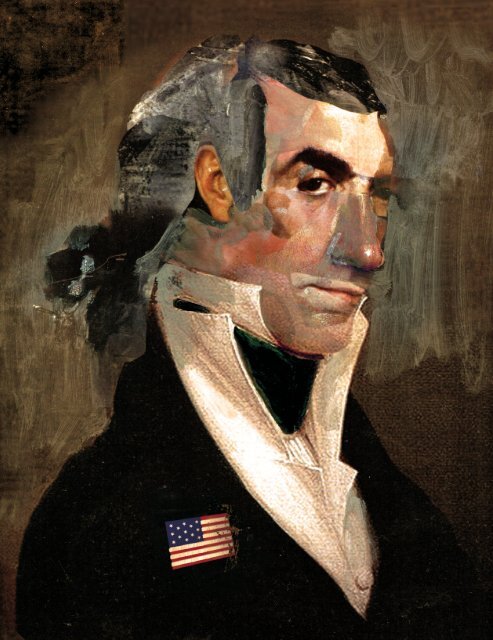

THERebelFrancis Hopkinsonsigned the Declaration <strong>of</strong> Independence,designed the American flag, wrote somebiting satire, composed the nation’s firstsecular music, and got some props for hisscientific ingenuity. Not a bad career for theCollege’s first alumnus. BY SAMUEL HUGHESDecember 16, 1776. War has come tothe rebellious American colonies. TheHessian Jäger Corps has marched intoBordentown, New Jersey, a small townon the Delaware River just northeast <strong>of</strong>Philadelphia. Captain Johann Ewald, theregiment’s commander, enters a handsomebrick house known to belong to aprominent rebel. Its library is filled withnumerous pieces <strong>of</strong> “scientific apparatus”—and, <strong>of</strong> course, lots <strong>of</strong> books. One, titledDiscourses on Public Occasions in America,by the Rev. William Smith—the provost <strong>of</strong>the College <strong>of</strong> Philadelphia and a staunch,though nuanced, Loyalist—catches Ewald’seye, and he plucks it from the shelf. Afterriffling through the pages he takes a penand writes, in German and beneath thebookplate <strong>of</strong> the book’s owner:“This man was one <strong>of</strong> the greatestRebels, nevertheless, if we dare to concludefrom the library and mechanicaland mathematical instruments, he musthave been a very learned Man also.”The learned rebel was Francis HopkinsonC1757 G1760 Hon1790, a member <strong>of</strong> thefirst graduating class <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong>Philadelphia, which would soon becomethe <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>. Most <strong>of</strong>the mechanical instruments had been lentto him by the College’s founder, BenjaminFranklin, who would later bequeath themall to Hopkinson and make him an executor<strong>of</strong> his will.Being described as “one <strong>of</strong> the greatestRebels” must have been quite the complimentto the diminutive, delicate-featuredHopkinson. Consider the description <strong>of</strong>him by John Adams four months earlierin a letter to his wife, Abigail. Having justmet Hopkinson at Charles Willson Peale’sart studio, Adams described him as a“painter and a poet” who had been “liberallyeducated,” adding:I have a curiosity to penetrate a littledeeper into the bosom <strong>of</strong> <strong>this</strong> curiousgentleman, and may possibly give yousome more particulars about him. He isone <strong>of</strong> your pretty, little, curious, ingeniousmen. His head is not bigger than alarge apple … I have not met with anythingin natural history more amusingand entertaining than his personalappearance; yet he is genteel and wellbred,and is very social.ILLUSTRATION BY DAVID HOLLENBACHTHE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE MAY | JUNE 2012 49

Philadelphia. (The plan was conceived andthree leading satirists on the Whig side shall strive to persuade the people to put52 MAY | JUNE 2012 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE<strong>of</strong> the American Revolution.” (Unlike theother two, John Trumbull and PhilipFreneau, Hopkinson “accomplished hiseffects without bitterness or violence.”)Some in Philadelphia knew that PeterGrievous was Francis Hopkinson. “Butto the members <strong>of</strong> the First ContinentalCongress, who did not know <strong>of</strong> <strong>this</strong> localwit and satirist, the story simply was anamazing allegorical account <strong>of</strong> Englandand the colonies,” noted George NicholsMarshall in Patriot with a Pen. “Manydelegates at the Congress bought copiesto mail home, and soon editor after editorbegan publishing it as a serial inlocal newspapers.”their trust in the rotten tree, and not todig it up, or remove it from its place. Andhe shall harangue with great vehemence,and shall tell them that a rotten tree isbetter than a found one; and that it isfor the benefit <strong>of</strong> the people that theNorth wind should blow upon it, andthat the branches there<strong>of</strong> should be brokenand fall upon and crush them.And he shall receive from the king <strong>of</strong> theislands, fetters <strong>of</strong> gold and chains <strong>of</strong> silver;and he shall have hopes <strong>of</strong> great reward ifhe will fasten them on the necks <strong>of</strong> thepeople, and chain them to the trunk <strong>of</strong> therotten tree … And his words shall be sweetin the mouth, but very bitter in the belly.executed by David Bushnell, the inventor<strong>of</strong> the first American submarine and otheraquatic weapons, though Hopkinson—then chairman <strong>of</strong> the Continental NavyBoard’s Middle Department—and hisfather-in-law, Joseph Borden, probably hada hand in the operation.) The kegs didn’thit any <strong>of</strong> the British ships anchored inthe Delaware on account <strong>of</strong> all the ice, butthey did explode—apparently killing atleast one curious boy—and drew fire fromsome <strong>of</strong> the British troops.Shortly after the event, a suspiciouslytongue-in-cheek prose account <strong>of</strong> theepisode appeared in local newspapers:“Some reported that these kegs werefilled with armed rebels, who were toLong before the Revolution, Benjamin In case the point wasn’t clear, Hopkinson issue forth in the dead <strong>of</strong> night, as didFranklin and William Smith, the concluded:the Grecians <strong>of</strong> old from their woodenfounder <strong>of</strong> the College and hishorse at the siege <strong>of</strong> Troy, and take thehand-picked provost, had fallen out [“YourMost Obedient Servant: The ProvostSmith Papers,” April 1997]. For some yearsAnd Cato and his works shall be no moreremembered amongst them. For Cato shalldie, and his works shall follow him.city by surprise,” the author claimed,“whilst others asserted they … would,<strong>of</strong> themselves, ascend the wharves inafter his graduation, Hopkinson was ablethe night-time, and roll all flamingto stay friends with both. But when itBYthe winter <strong>of</strong> 1777-78, things through the streets <strong>of</strong> the city, destroyingevery thing in their way.”came time to take a stand, Hopkinsonwere looking pretty grim foremphatically sided with Franklin.the American cause. General From the British warships, “whole broadsidesIn “A Prophecy: Written in 1776”Hopkinson used a Biblical style to tell hisstory about a “new people” in a “far country,”who will soon be given a tree by the“king <strong>of</strong> islands.” But a certain “Northwind” will arise and “blast the tree, so thatit shall no longer yield its fruit, or affordshelter to the people, but it shall becomerotten at the heart …” Then, he wrote:William Howe’s British troops occupiedPhiladelphia, and George Washington’ssoldiers were freezing and dying atValley Forge. The rebellious spirits badlyneeded a lift.On January 5, a flotilla <strong>of</strong> kegs, filledwith gunpowder and designed to explodeon contact with anything they bumpedinto, was pushed into the Delaware Riverfrom a point several miles north <strong>of</strong>were poured into the Delaware,”and “not a wandering chip, stick, or driftlog, but felt the vigor <strong>of</strong> the British arms.”That day, the writer concluded, “mustever be distinguished in history for thememorable battle <strong>of</strong> the kegs.”The anonymous writer was almost certainlyHopkinson, who used the finalphrase as the title <strong>of</strong> the 88-line satiricalpoem that would be published in Thea prophet shall arise from amongst <strong>this</strong>people, and he shall exhort them, andinstruct them in all manner <strong>of</strong> wisdom,and many shall believe in him; and heshall wear spectacles upon his nose;and reverence and esteem shall restupon his brow.Just how much Franklin influencedHopkinson’s opinion <strong>of</strong> Smith is impossibleto say, but the bottom line is thatHopkinson had no qualms about penningsome harsh words about his oldprovost—whose series <strong>of</strong> letters signedCato had warned <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>ns thatthey had “much to lose in <strong>this</strong> contest.”(Those letters were themselves aresponse to Thomas Paine’s “CommonSense.”) In Hopkinson’s “Prophecy,” theman who called himself CatoUNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

<strong>Pennsylvania</strong> Packet on March 4. (Tohear it read aloud, visit our website,www.upenn.edu/gazette.)“The Battle <strong>of</strong> the Kegs,” which even referencedHowe’s married Philadelphia mistress,“soon was read in papers all over thecolonies, memorized by regimental bardsand barroom buffoons,” noted GeorgeMarshall. “The account <strong>of</strong> the ridiculousBritish navy fighting an unseen enemy inthe Delaware burst the seams and tickledthe funny bones <strong>of</strong> the colonists.”Hopkinson’s merriment was only temporary,as in May <strong>of</strong> that year, anothertroop <strong>of</strong> British soldiers marched intoBordentown, and <strong>this</strong> time they pillagedhis house and burned that <strong>of</strong> his fatherin-law.“I have suffered much by the Invasion <strong>of</strong>the Goths & Vandals,” Hopkinson wrote toFranklin, then in France. “The Savagesplundered me to their Hearts’ content—but I do not repine, as I really esteem it anhonour to have suffered in my Country’sCause in Support <strong>of</strong> the Rights <strong>of</strong> humannature and <strong>of</strong> civil Society.”Hopkinson enclosed the “The Battle <strong>of</strong>the Kegs” and another satirical piece titled“Date Obolum Belesario,” to which Franklinreplied: “I thank you for the political Squibs;they are well made. I am glad to find suchplenty <strong>of</strong> good powder.”The poem became even more popularonce it was set to music. By July 10,1780, Continental Army Surgeon JamesThacher was writing in his journal aboutDesigns for Wine and CountryOn May 25, 1780, Francis Hopkinson submitted a request forpayment for certain “labours <strong>of</strong> fancy” to the Continental MarineCommittee and Board <strong>of</strong> Admiralty with the following comments:It is with great pleasure that I understand that my last Device<strong>of</strong> a Seal for the Board <strong>of</strong> Admiralty has met with your Honours’Approbation. I have with great Readiness, upon several Occasionsexerted my small Abilities in <strong>this</strong> Way for the public Service; &, as Iflatter myself, to the Satisfaction <strong>of</strong> those I wish’d to please, vizThe Flag <strong>of</strong> the United States <strong>of</strong> America7 Devices for the Continental CurrencyA Seal for the Board <strong>of</strong> TreasuryOrnaments, Devices & Checks for the new Bills <strong>of</strong> Exchangein Spain & HollandA Seal for the Ship Papers <strong>of</strong> the United StatesA Seal for the Board <strong>of</strong> AdmiraltyThe Borders, Ornaments & Checks for the new ContinentalCurrency now in the Press,—a Work <strong>of</strong> considerable LengthA great Seal for the United States <strong>of</strong> America, with a Reverse.—For these Services I have as yet made no Charge, nor receivedany Recompense. I now submit to your Honour’s Consideration,whether a Quarter Cask <strong>of</strong> the public Wine will be a proper & areasonable Reward for these Labours <strong>of</strong> Fancy and a suitableEncouragement to future Exertions <strong>of</strong> a like Nature.His claim to have designed the American flag—which he sometimesreferred to as the “Naval flag <strong>of</strong> the United States”—isn’tdoubted by those who have studied the matter. (Even the USPostal Service, which tries hard to avoid stepping into unsettledhistorical debates, honored Hopkinson as “Father <strong>of</strong> the Starsand Stripes” on Flag Day 20 years ago.) One <strong>of</strong> his designsplaced the stars in symmetrical rows, while another had them ina circle. True, they were six-pointed stars—probably taken froma festive evening near Passaic Falls inNew Jersey: “Our drums and fifes affordedus a favorite music till evening, whenwe were delighted with the song composedby Mr. Hopkinson, called, the‘Battle <strong>of</strong> the Kegs,’ sung in the beststyle by a number <strong>of</strong> gentlemen.”On December 11, 1781, less than twomonths after the decisive Battle <strong>of</strong> Yorktown,a musical work titled “The Temple<strong>of</strong> Minerva, An Oratorial Entertainment”was performed in Philadelphia. Amongthose in attendance were Anne-César Dela Luzerne, the French Ambassador to theUnited States; General and Martha Washingtonand General Nathanael Greene;and Hopkinson, the composer <strong>of</strong> the work.the family crest he brought back from a visit to England—not thefive-pointed stars that were eventually used in the flag sewn byBetsy Ross. But that’s a pretty minor adjustment.“Of all candidates, he is the most likely designer <strong>of</strong> the starsand stripes,” says Edward W. Richardson in Standards and Colors<strong>of</strong> the American Revolution, while A History <strong>of</strong> the United StatesFlag, published by the Smithsonian Institution, states: “The journals<strong>of</strong> the Continental Congress clearly show that [Hopkinson]designed the flag,” adding that the authors <strong>of</strong> that volume had“no question that he designed the flag <strong>of</strong> the United States.”And even though his enemies blocked all attempts to have himpaid for his services, “they never denied that he made the designs.”Hopkinson never did get his quarter-cask <strong>of</strong> wine, even thoughit seems, from <strong>this</strong> vantage point, a pretty reasonable recompensefor the time and graphic-design talent required—notto mention the enduring quality <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the designs. TheCommissioners <strong>of</strong> the Chamber <strong>of</strong> Accounts concluded that thecharge was “reasonable and ought to be paid.” But he ran afoul<strong>of</strong> bureaucratic nitpicking and some personal animosity from hisenemies in the Board <strong>of</strong> Treasury, who said that he had neglectedto submit any vouchers supporting his requests. When he resubmittedthe bill, <strong>this</strong> time for money ($7,200, which sounds like alot but wasn’t, given the weak state <strong>of</strong> the dollar), the Board <strong>of</strong>Treasury again postponed the matter, sniping that he “was notthe only person consulted on these exhibitions <strong>of</strong> fancy” and thus“wasn’t entitled to the full sum charged.” When he went to its<strong>of</strong>fices in person, the door was literally slammed in his face.Congress appointed a committee to investigate the quarreland, when the Board <strong>of</strong> Treasury refused to appear before it,issued a report that lambasted the behavior <strong>of</strong> its secretary andtwo commissioners as “very reprehensible, extremely disgusting,and has destroyed all friendly communication <strong>of</strong> Counsels,and harmony in the execution <strong>of</strong> Public Affairs.” It recommendedthe dismissal <strong>of</strong> all three men, but that too got bogged downin bureaucratic torpor. All <strong>this</strong> while a war was going on. —S.H.THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE MAY | JUNE 2012 53

had to tailor his lines around their works.Originally titled “America Independent,” the victorious generals. But while a review54 MAY | JUNE 2012 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTEthe work was a “dramatic allegorical cantata,”in the words <strong>of</strong> musical historianOscar Sonneck, who called Hopkinson“America’s first poet-composer.”Set in front <strong>of</strong> the Temple <strong>of</strong> Minerva(the goddess <strong>of</strong> wisdom), the cantata’sthree male figures—the Genius <strong>of</strong>France, the Genius <strong>of</strong> America, and theHigh Priest <strong>of</strong> Minerva—prayed for thegoddess to appear and make a predictionabout the new nation <strong>of</strong> Columbia.When she made her entrance in Act II,Minerva predicted that a happy statewould repay all <strong>of</strong> Columbia’s grief, andthat if her sons would stand united,“great and glorious shall she be.”The outcome <strong>of</strong> the war was still verymuch in doubt when Hopkinson composed“The Temple <strong>of</strong> Minerva,” whichgave its cautiously optimistic words aneven sweeter ring when performed beforein The Freeman’s Journal the followingweek said that the performance “affordedthe most sensible pleasure,” the Toryresponse can be gleaned from a parodypublished in the January 5, 1782 issue <strong>of</strong>the Royal Gazette: “The Temple <strong>of</strong>Cloacina: An Ora-whig-ial Entertainment.”In that version—which consisted <strong>of</strong> aseverely pencil-edited copy <strong>of</strong> the original—thetemple was an outhouse. In alengthy 1976 <strong>article</strong> for the Proceedings <strong>of</strong>the American Philosophical Society, musicologistGillian B. Anderson described theentire parody as shockingly obscene.Hopkinson himself told BenjaminFranklin that “The Temple <strong>of</strong> Minerva”was “not very elegant Poetry, but theEntertainment consisted in the Music &went <strong>of</strong>f very well.” Since the music consisted<strong>of</strong> works by Handel and other composersas well as his own, he explained, he“In short, the Musician crampt the Poet.”Whatever the critical assessments <strong>of</strong>Hopkinson’s music, we know that itsometimes had a strong effect on listeners.When he sent a collection <strong>of</strong> hispopular songs to Thomas Jefferson, thenthe US Ambassador to France, Jeffersonresponded that “while my elder daughterwas playing [one song] on the harpsichord,I happened to look toward thefire, & saw the younger one all in tears. Iasked her if she were sick? She said, ‘No;but the tune was so mournful.’”Hopkinson later sent a copy <strong>of</strong> hissong book to Washington, with the followingcomment:However small the Reputation may be thatI shall derive from <strong>this</strong> Work, I cannot, Ibelieve, be refused the Credit <strong>of</strong> being thefirst Native <strong>of</strong> the United States who hasA year <strong>of</strong> war apparently changed his mind. When GeneralFrom Bluecoat toWilliam Howe’s troops marched into Philadelphia on September26, 1777, Duché prayed aloud for the king at Christ Church. HeRedcoat, a Turncoat was promptly arrested and thrown into jail, though quickly released.Three weeks later he would resign as chaplain to Congress, citingOn September 7, 1774, Jacob Duché C1757 G1760 was askedto give the opening prayer for the First Continental Congress atCarpenters Hall. Having served as pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> oratory for thepast 15 years at the College <strong>of</strong> Philadelphia, where he was atrustee and a former valedictorian <strong>of</strong> his class, he knew howto move people with words. And as rector <strong>of</strong> Christ Church, themost prestigious Anglican church in Philadelphia, his words carriedconsiderable weight.Duché gave Congress what it wanted that day, and then some.He began by imploring the Almighty to “look down in mercy” on“these our American States, who have fled to Thee from the rod<strong>of</strong> the oppressor and thrown themselves on Thy gracious protection,desiring to be henceforth dependent only on Thee.” He alsoprayed for the Americans to “defeat the malicious designs <strong>of</strong> ourcruel adversaries; convince them <strong>of</strong> the unrighteousness <strong>of</strong> theirCause and … constrain them to drop the weapons <strong>of</strong> war fromtheir unnerved hands in the day <strong>of</strong> battle!”The effect <strong>of</strong> his words was electric.“I must confess I never heard a better prayer … with such fervor,such ardor, earnestness and pathos, and in a language soelegant and sublime for America [and] for the Congress,” wroteJohn Adams in a letter to his wife Abigail. More to the point, “Inever saw a greater effect upon an audience.”Duché was still aboard the Revolutionary bandwagon inJuly 1776 when the Second Continental Congress signed theDeclaration <strong>of</strong> Independence. He and the vestry <strong>of</strong> Christ Churchpassed a resolution removing all references to King George III, andfive days later Congress voted to make him its first <strong>of</strong>ficial chaplain.the pressure <strong>of</strong> work and poor health.But by then he had already written a letter to General GeorgeWashington that would change his reputation in the eyes <strong>of</strong> historyforever. Given the incendiary contents, it’s worth quoting atsome length.After saying that “all the world” knew that Washington’smotives for serving his country were “perfectly disinterested,”Duché expressed shocked disbelief at the cause to which hehad committed himself and his country: “What then can be theconsequence <strong>of</strong> <strong>this</strong> rash and violent measure and degeneracy <strong>of</strong>representation, confusion <strong>of</strong> councils, blunders without number?”He pooh-poohed the <strong>Pennsylvania</strong> faction for “the weakness <strong>of</strong>their understandings, and the violence <strong>of</strong> their tempers,” and dismissedthe other states’ Congressmen as a bunch <strong>of</strong> “Bankrupts,attorneys,—and men <strong>of</strong> desperate fortunes,” adding: “Longbefore they left Philadelphia, their dignity and consequence wasgone; what must it be now since their precipitate retreat?” (Hisone unnamed exception was presumably his brother-in-law andformer classmate, Francis Hopkinson: “a man <strong>of</strong> virtue, draggedreluctantly into their measures, and restrained, by some falseideas <strong>of</strong> honour, from retreating, after having gone too far.”)After heaping contempt on the American military effort—“yourharbours are blocked up, your cities fall one after another;fortress after fortress, battle after battle is lost … How unequalthe contest! How fruitless the expence <strong>of</strong> blood?”—Duchéthen made his pitch: “represent to Congress the indispensiblenecessity <strong>of</strong> rescinding the hasty and ill-advised declaration<strong>of</strong> Independency,” and recommend “an immediate cessation

produced a Musical Composition. If <strong>this</strong>attempt should not be too severely treated,others may be encouraged to venture on apath, yet untrodden in America, and theArts in succession will take root and flourishamongst us.Washington’s answer was both generousand diplomatic. While he himselfcould “neither sing one <strong>of</strong> the songs, norraise a single note on any instrument toconvince the unbelieving,” he wrote, hecould <strong>of</strong>fer “one argument which willprevail with persons <strong>of</strong> true taste (atleast in America)—I can tell them that itis the production <strong>of</strong> Mr. Hopkinson.”Hopkinson’s contributions to theAmerican cause didn’t end withthe Revolution. By the crucialyear <strong>of</strong> 1787, he had become a firmFederalist. In that arena, true to form,he’s probably best known for “The NewRo<strong>of</strong>,” the allegorical essay and poemhe wrote about replacing the Articles<strong>of</strong> Confederation with a new constitution.(The poem was originally titled“The Raising: A New Song for FederalMechanics.”)The gist <strong>of</strong> the prose version goeslike <strong>this</strong>: Despite being only 12 yearsold, the “ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> a certain mansionhouse” had decayed so badly that itcould no longer provide protectionfrom the weather. When a group <strong>of</strong>“skillful architects” examined it, theyfound that the “whole frame was tooweak”; that its 13 rafters were “not connectedby any braces or ties so as t<strong>of</strong>orm a union <strong>of</strong> strength”; that “some<strong>of</strong> these rafters were thick and heavy,and others very slight”; that the “lathingand shingling had not been securedwith iron nails but only wooden pegs,”which would shrink and swell in thesun and rain—causing the shingles tobecome “so loose that many <strong>of</strong> themhad been blown away by the winds.”Finally, the ro<strong>of</strong> was “so flat as to admitthe most idle servants in the family,their playmates and acquaintances, totrample upon and abuse it.”In order to build a new and better ro<strong>of</strong>,the architects “consulted the most celebratedauthors in ancient and modernarchitecture” and tried to “proportionthe whole to the size <strong>of</strong> the building andstrength <strong>of</strong> the walls.” (The validity <strong>of</strong>his imagery is still debated; in a recentessay titled “A Ro<strong>of</strong> without Walls: TheDilemma <strong>of</strong> an American NationalIdentity,” historian John Murrin wrote:“Francis Hopkinson to the contrary,Americans had erected their constitutionalro<strong>of</strong> before they put up the nationalwalls.” But that’s another story.)<strong>of</strong> hostilities.” Then appoint some “men <strong>of</strong> clear and impartialcharacters, in or out <strong>of</strong> Congress … to confer with his Majesty’scommissioners” with some “some well-digested constitutionalplan.” And since “millions will bless the hero that left the field <strong>of</strong>war, to decide <strong>this</strong> most important contest with the weapons <strong>of</strong>wisdom and humanity,” he added: “Oh! Sir, let no false ideas <strong>of</strong>worldly honour deter you from engaging in so glorious a task …”Finally, if Washington couldn’t persuade Congress to negotiatea surrender, Duché suggested that he still had “an infalliblerecourse” at his disposal: “negociate for your country atthe head <strong>of</strong> your army.” In other words, sell out your country insecret and save your own hide.Washington promptly turned the letter over to Congress. Hethen wrote a letter to Hopkinson, who was serving the patriotcause in a number <strong>of</strong> capacities. (See main story.) Had “any accidenthave happened to the army entrusted to my command, andhad it ever afterwards have appeared that such a letter had been… received by me,” Washington explained, “might it not havebeen said that I had, in consequence <strong>of</strong> it, betrayed my country?”Washington was clearly appalled at having received “soextraordinary a letter” from Duché, “<strong>of</strong> whom I had entertainedthe most favorable opinion, and I am still willing to suppose,that it was rather dictated by his fears than by his real sentiments.”But, he told Hopkinson, “I very much doubt whether thegreat numbers <strong>of</strong> respectable characters, in the state and army,on whom he has bestowed the most unprovoked and unmeritedabuse, will ever … forgive the man, who has artfully endeavoredto engage me to sacrifice them to purchase my own safety.”If Washington was appalled, Hopkinson was apoplectic.“Words cannot express the Grief and Consternation thatwounded my Soul at the Sight <strong>of</strong> <strong>this</strong> fatal Performance,” hewrote to Duché. “What Infatuation could influence you to <strong>of</strong>ferto his Excellency an Address fill’d with gross Misrepresentations,illiberal Abuse and sentiments unworthy <strong>of</strong> a Man <strong>of</strong> Character?… I could go thro’ <strong>this</strong> extraordinary letter, and point out to youthe Truth distorted in every leading part. But the World willdoubtless do <strong>this</strong> with a Severity that must be Daggers to theSensibilities <strong>of</strong> your Heart.”Apart from the moral failure, Hopkinson warned: “You will findthat you have drawn upon you the Resentment <strong>of</strong> Congress,the resentment <strong>of</strong> the Army, the resentment <strong>of</strong> many worthyand noble characters in England whom you know not, and theresentment <strong>of</strong> your insulted Country …“You presumptuously advise our worthy General, on whomMillions depend with implicit Confidence, to abandon their dearestHopes, and with or without the Consent <strong>of</strong> his Constituentsto negotiate for America at the head <strong>of</strong> his Army. Would not theBlood <strong>of</strong> the Slain in Battle rise against such Perfidy? …“I am perfectly disposed to attribute <strong>this</strong> unfortunate step tothe Timidity <strong>of</strong> your Temper, the weakness <strong>of</strong> your Nerves, andthe undue Influence <strong>of</strong> those about you,” Hopkinson told hisold friend and brother-in-law. “But will the World hold you soexcused? Will the Individuals whom you so freely censured andcharacterized with Contempt have <strong>this</strong> tenderness for you? Ifear not … I pray God to inspire you with some Means <strong>of</strong> extricatingyourself from <strong>this</strong> embarrassing Difficulty.”For his own part, Hopkinson said, “I have well considered thePrinciples on which I took part with my Country and am determinedto abide by them to the last Extremity.” Asking Duché tosend his love to his mother and sisters in Philadelphia, he concluded:“May God preserve them and you in <strong>this</strong> Time <strong>of</strong> Trial.”Duché fled to England the following year, and when theAmerican army re-entered Philadelphia, his property was confiscated.Hopkinson interceded on behalf <strong>of</strong> his sister and her childrento recoup enough money to pay their passage to London.The two classmates never saw each other again. —S.H.THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE MAY | JUNE 2012 55

“The New Ro<strong>of</strong>” was widely read andwell received in its day—though againtrue to form, Hopkinson’s potshots atthe Anti-Federalist camp (too complicatedto go into here) sparked somereturn fire. One opponent called him a“base parasite and tool <strong>of</strong> the wealthyand great, at the expense <strong>of</strong> truth, honor,friendship,” and added: “Little Francisshould have been cautious in givingprovocation, for insignificance alonecould have preserved him the smallestremnant <strong>of</strong> character.”Hopkinson had the last laugh, though. On July 4,1788, Philadelphia—which had waited until 10states had ratified the Constitution—celebratedwith a “Grand Federal Procession” that was both wildly propagandisticand a spectacular success. Hopkinson himself,the Grand Marshal, planned and directed the whole event.Its 87 divisions consisted <strong>of</strong> floats, allegorical figures, andgroups; bands and military organizations; state, national,and foreign <strong>of</strong>ficials; delegations from various societies;and representatives <strong>of</strong> trades and pr<strong>of</strong>essions ranging fromstone-cutters and farmers (motto: “Venerate the Plough”) togun-smiths and sugar refiners (“Double Refined”).“The rising sun was saluted with a full peal from ChristChurch steeple,” wrote Hopkinson, followed by a “discharge<strong>of</strong> cannon from the ship, Rising Sun … anchored<strong>of</strong>f Market Street, and superbly decorated with the flags<strong>of</strong> nations in alliance with America.” About 5,000 people56 MAY | JUNE 2012 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE

marched or rode in horse-pulled floats inthe procession itself, which started atThird and South streets and arrived atUnion Green, part <strong>of</strong> the Bush Hill estatenorth and west <strong>of</strong> 12th and Market. Franklin,then president <strong>of</strong> the Supreme ExecutiveCouncil <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>, was “toomuch indisposed” to attend, but Hopkinsonmarched in a division representingthe state’s Court <strong>of</strong> Admiralty, which heknew would be made obsolete by the Constitution.The chief justice <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>’sSupreme Court rode in a 13-foot-tallbald eagle, its breast emblazoned with 13silver stars and its talons clutching anolive branch and 13 silver arrows. (Eatyour heart out, Stephen Colbert.) “Students<strong>of</strong> the university, headed by thevice-provost,” marched with representatives<strong>of</strong> the city’s other schools, holding asmall flag inscribed The Rising Generation,Hopkinson noted, while at the end<strong>of</strong> the procession marched lawyers, physicians,and “the clergy <strong>of</strong> the differentChristian denominations, with the rabbi<strong>of</strong> the Jews, walking arm in arm.”And the most imposing float in theprocession was the “New Ro<strong>of</strong>, or GrandFederal Edifice,” designed by CharlesWillson Peale: a 30-foot-tall circulartemple with 10 Corinthian columns (andspaces for the columns representing thethree still-unratified states) and a ro<strong>of</strong>whose cupola was crowned by the figure<strong>of</strong> Plenty, holding her cornucopia. Thewords In Union the Fabric Stands Firmwere carved into the base.At Union Green, James Wilson [“FlawedFounder,” May|June 2011] climbed ontothe Grand Federal Edifice and delivereda speech to an audience <strong>of</strong> about17,000 people.“A people, free and enlightened, establishingand ratifying a system <strong>of</strong> governmentwhich they have previouslyconsidered, examined, and approved!” hetold them. “This is the spectacle whichwe are assembled to celebrate; and it isthe most dignified one that has yetappeared on our globe.”After the address, the assembled multitudeshad dinner, where they wereserved locally made porter, beer, andcider, and drank toasts to, well, prettymuch everybody.A year later, the newly electedPresident Washington sent Hopkinsona letter informing him that the Senatehad confirmed his appointment as afederal judge for the US District Courtfor <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>. In congratulatinghim, Washington wrote: “I have endeavouredto bring into the <strong>of</strong>fices … suchCharacters as will give stability anddignity to our national Government.”In November 1790, Hopkinson wasawarded an honorary Doctorate <strong>of</strong> Lawdegree by the penultimate incarnation <strong>of</strong>his alma mater, the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> the State<strong>of</strong> <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>. A year later it would mergewith the briefly resuscitated College <strong>of</strong>Philadelphia (which had been closed duringmost <strong>of</strong> the Revolution for its overlyTory ways) into a single institution: the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pennsylvania</strong>.On the morning <strong>of</strong> May 9, 1791,Hopkinson was “seized with an apoplecticfit,” in the words <strong>of</strong> Benjamin Rush,“which in two hours put a period to hisexistence, in the 53d year <strong>of</strong> his age.” Hewas buried in the Christ Church graveyard,not far from Franklin, who haddied the previous year. Among the provisionsin Hopkinson’s will was one thatwould free his two “Negro Slaves Danand Violet,” though only after the death<strong>of</strong> his wife. An anonymous contemporary<strong>of</strong> Hopkinson’s wrote:“And be <strong>this</strong> truth upon his marble writ—He shone in virtue, science, taste, and wit.”Over the decades, his gravestonedeteriorated to the point that no oneknew for certain where his remainswere buried. Finally, in the 1930s, aplot believed to be Hopkinson’s wasdug up. The skeletal remains were sentto Penn Anatomy Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Oscar V.Batson, who concluded that they wereindeed Hopkinson’s.After his old bones were re-buried, anew headstone was placed over them,<strong>this</strong> time with a plaque listing his mostsignificant accomplishments. It’s apretty impressive list. But it doesn’tbegin to tell the whole story.◆THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE MAY | JUNE 2012 57