Reducing habitat fragmentation by minor rural roads through traffic ...

Reducing habitat fragmentation by minor rural roads through traffic ...

Reducing habitat fragmentation by minor rural roads through traffic ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

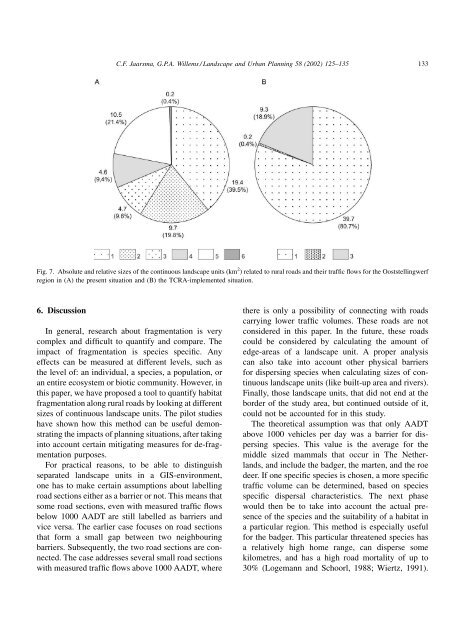

C.F. Jaarsma, G.P.A. Willems / Landscape and Urban Planning 58 (2002) 125–135 133Fig. 7. Absolute and relative sizes of the continuous landscape units (km 2 ) related to <strong>rural</strong> <strong>roads</strong> and their <strong>traffic</strong> flows for the Ooststellingwerfregion in (A) the present situation and (B) the TCRA-implemented situation.6. DiscussionIn general, research about <strong>fragmentation</strong> is verycomplex and difficult to quantify and compare. Theimpact of <strong>fragmentation</strong> is species specific. Anyeffects can be measured at different levels, such asthe level of: an individual, a species, a population, oran entire ecosystem or biotic community. However, inthis paper, we have proposed a tool to quantify <strong>habitat</strong><strong>fragmentation</strong> along <strong>rural</strong> <strong>roads</strong> <strong>by</strong> looking at differentsizes of continuous landscape units. The pilot studieshave shown how this method can be useful demonstratingthe impacts of planning situations, after takinginto account certain mitigating measures for de-<strong>fragmentation</strong>purposes.For practical reasons, to be able to distinguishseparated landscape units in a GIS-environment,one has to make certain assumptions about labellingroad sections either as a barrier or not. This means thatsome road sections, even with measured <strong>traffic</strong> flowsbelow 1000 AADT are still labelled as barriers andvice versa. The earlier case focuses on road sectionsthat form a small gap between two neighbouringbarriers. Subsequently, the two road sections are connected.The case addresses several small road sectionswith measured <strong>traffic</strong> flows above 1000 AADT, wherethere is only a possibility of connecting with <strong>roads</strong>carrying lower <strong>traffic</strong> volumes. These <strong>roads</strong> are notconsidered in this paper. In the future, these <strong>roads</strong>could be considered <strong>by</strong> calculating the amount ofedge-areas of a landscape unit. A proper analysiscan also take into account other physical barriersfor dispersing species when calculating sizes of continuouslandscape units (like built-up area and rivers).Finally, those landscape units, that did not end at theborder of the study area, but continued outside of it,could not be accounted for in this study.The theoretical assumption was that only AADTabove 1000 vehicles per day was a barrier for dispersingspecies. This value is the average for themiddle sized mammals that occur in The Netherlands,and include the badger, the marten, and the roedeer. If one specific species is chosen, a more specific<strong>traffic</strong> volume can be determined, based on speciesspecific dispersal characteristics. The next phasewould then be to take into account the actual presenceof the species and the suitability of a <strong>habitat</strong> ina particular region. This method is especially usefulfor the badger. This particular threatened species hasa relatively high home range, can disperse somekilometres, and has a high road mortality of up to30% (Logemann and Schoorl, 1988; Wiertz, 1991).