Picasso Takes on the Masters - Phs.poteau.k12.ok.us

Picasso Takes on the Masters - Phs.poteau.k12.ok.us

Picasso Takes on the Masters - Phs.poteau.k12.ok.us

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

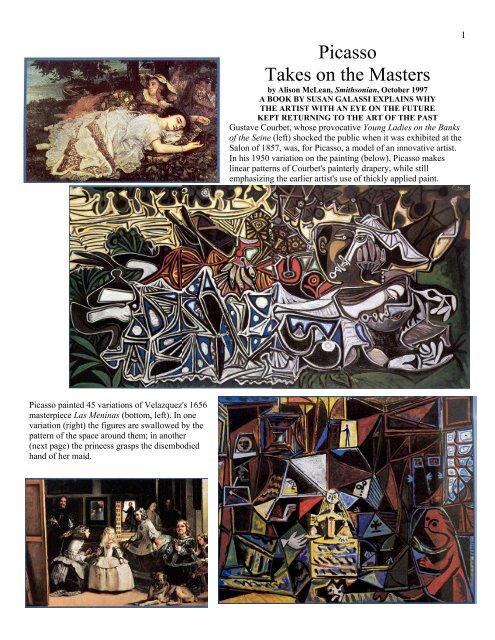

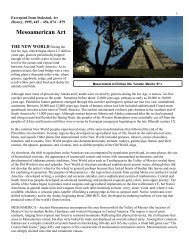

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Takes</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Masters</strong>by Alis<strong>on</strong> McLean, Smiths<strong>on</strong>ian, October 1997A BOOK BY SUSAN GALASSI EXPLAINS WHYTHE ARTIST WITH AN EYE ON THE FUTUREKEPT RETURNING TO THE ART OF THE PASTG<strong>us</strong>tave Courbet, whose provocative Young Ladies <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Banksof <strong>the</strong> Seine (left) shocked <strong>the</strong> public when it was exhibited at <strong>the</strong>Sal<strong>on</strong> of 1857, was, for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>, a model of an innovative artist.In his 1950 variati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> painting (below), <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> makeslinear patterns of Courbet's painterly drapery, while stillemphasizing <strong>the</strong> earlier artist's <strong>us</strong>e of thickly applied paint.1<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> painted 45 variati<strong>on</strong>s of Velazquez's 1656masterpiece Las Meninas (bottom, left). In <strong>on</strong>evariati<strong>on</strong> (right) <strong>the</strong> figures are swallowed by <strong>the</strong>pattern of <strong>the</strong> space around <strong>the</strong>m; in ano<strong>the</strong>r(next page) <strong>the</strong> princess grasps <strong>the</strong> disembodiedhand of her maid.

2“THE PAINTER TAKES WHATEVER IT IS AND DESTROYS IT. At <strong>the</strong>Same time, He gives it ano<strong>the</strong>r life.”---Pablo <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>"A painter's atelier should be a laboratory," said Pablo <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> in 1945. "Onedoesn't do a m<strong>on</strong>key's job here: <strong>on</strong>e invents." <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>, <strong>the</strong> inventor of whole newsystems of painting for <strong>the</strong> 20th century, never aped <strong>the</strong> accomplishments of pastmasters. Yet throughout his career he explored issues of style, structure andmeaning by creating variati<strong>on</strong>s of works by o<strong>the</strong>r artists.These explorati<strong>on</strong>s are <strong>the</strong> subject of a book by S<strong>us</strong>an Galassi, associate curator of<strong>the</strong> Frick Collecti<strong>on</strong> in New York and a <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> scholar. Published by Harry N.Abrams, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s Variati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Masters</strong>: C<strong>on</strong>fr<strong>on</strong>tati<strong>on</strong>s with <strong>the</strong> Pastdocuments <strong>the</strong> artist's lifel<strong>on</strong>g <strong>us</strong>e of his predecessors' work as a spark for his owncreative processes, and as a way of dem<strong>on</strong>strating his own place in <strong>the</strong> traditi<strong>on</strong> ofEuropean art.In his early years, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s occasi<strong>on</strong>al variati<strong>on</strong>s were fueled by asense of competiti<strong>on</strong> with past artists. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> was fascinated by <strong>the</strong>work of <strong>the</strong> French Neoclassical artist Jean-Aug<strong>us</strong>te-DominiqueIngres. In Odalisque, After Ingres, an early variati<strong>on</strong> d<strong>on</strong>e in 1907when he was 26, for example, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> ignores <strong>the</strong>face and character of <strong>the</strong> woman in Ingres's GrandOdalisque (right), c<strong>on</strong>centrating instead <strong>on</strong>defining her structure and surroundings. TakingIngres's subtle distorti<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> figure severaldegrees fur<strong>the</strong>r, he translates Ingres's recliningnude into his own recently-developed Cubist style.Many of <strong>the</strong> variati<strong>on</strong>s are inf<strong>us</strong>ed with <strong>the</strong> artist'ssense of humor; in a parody of Manet's Olympia,<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> inserts a portrait of himself into <strong>the</strong> scenein <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> courtesan's client.In 1957, at age 76, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> spent four intense m<strong>on</strong>ths producing 45 variati<strong>on</strong>s of Velazquez's masterpiece Las Meninasfrom 1656. These works, Galassi points out, are a "process of c<strong>on</strong>tinuo<strong>us</strong> transformati<strong>on</strong>." This transformati<strong>on</strong> is mostvisible in <strong>the</strong> 14 works that foc<strong>us</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> central character of Velazquez's painting, <strong>the</strong> young Spanish princess. Sheappears in some as a series of refined Cubist abstracti<strong>on</strong>s and in ano<strong>the</strong>r as a glow of expressi<strong>on</strong>ist energy; in a morenaturalistic versi<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> artist gives her <strong>the</strong> features of his daughter Paloma. In <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s mind <strong>the</strong>re was no more truth in<strong>the</strong> last painting than <strong>the</strong> first; for him creativity involved c<strong>on</strong>stant change. "A picture," he had said to a friend in 1935,"lives a life like a living creature, undergoing <strong>the</strong> changes imposed <strong>on</strong> <strong>us</strong> by our life from day to day."“When I paint I feel that all <strong>the</strong> artists of <strong>the</strong> past are behind me.”---Pablo <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>

3“What I really like aboutel Greco are his portraitsof <strong>the</strong>se gentlemen with<strong>the</strong>ir pointed hands.”--Pablo<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>In his Portrait of aPainter, after El Greco,from 1950 (right),<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> transforms <strong>the</strong> direct gaze of <strong>the</strong> painter in El Greco’sportrait of his s<strong>on</strong> (above); <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>’s painter, whose profile issuperimposed <strong>on</strong> his fr<strong>on</strong>tal face, could <strong>on</strong>ly have Cubistvisi<strong>on</strong>.“Cubism is no different from any o<strong>the</strong>r school of painting.The same principles and <strong>the</strong> same elements are comm<strong>on</strong> toall.”--Pablo <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s work remains extremely popular. "I think we'vestayed interested in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> beca<strong>us</strong>e his work encompasses somuch of <strong>the</strong> past," says Galassi. "Although he set up a whole new c<strong>on</strong>cept of art for <strong>the</strong> 20th century, he was workingwithin <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>text of art history. The dialogue was always <strong>the</strong>re."By Alis<strong>on</strong> McLean888888888888888Excerpted from Kathleen Krull, Lives of <strong>the</strong> Artists, 1995, 54 – 59.AT THE BULLFIGHTSPABLO PICASSOBORN IN MALAGA, SPAIN, 1881DIED IN MOUGINS, FRANCE, 1973Spanish painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and ceramicist-C<strong>on</strong>sidered <strong>the</strong> foremost figure ofTwentieth-century artPABLO PICASSO grew up indulged by <strong>the</strong> five women in his ho<strong>us</strong>ehold. He hated authority and was not a goodstudent—possibly beca<strong>us</strong>e of dyslexia, he had trouble learning to read and write. Instead of doing his schoolwork, hewould bring a pige<strong>on</strong> to class and spend his time drawing it.

He had his first exhibit at age thirteen, when he showed hispaintings in <strong>the</strong> back room of an umbrella store. Later he hungout at <strong>the</strong> Cafe Four Cats and had an exhibit <strong>the</strong>re, too, but <strong>the</strong><strong>on</strong>ly works that sold were to people whose portraits he had d<strong>on</strong>e.He left for Paris at age eighteen, wearing his black corduroy suit.J<strong>us</strong>t before his departure, he wrote <strong>on</strong> his most recent selfportrait:"I <strong>the</strong> king. I <strong>the</strong> king. I <strong>the</strong> king."4In Paris, though, he lived less than royally. His home was agarret; he worked by <strong>the</strong> light of a single candle he stuck into abottle. Occasi<strong>on</strong>ally he could not even afford <strong>the</strong> candle. He<strong>us</strong>ed books for pillows, sometimes burned drawings to keepwarm, kept a white mo<strong>us</strong>e as a pet, and ate fried potatoes, beans,and omelettes.When his place was robbed, thieves stole everything but his art.Whenever he had enough m<strong>on</strong>ey he went to <strong>the</strong> bullfights,which he had loved as a child, fascinated by <strong>the</strong> bullfighters'lack of fear. One of his nicknames for himself was Eye of <strong>the</strong>Bull, and he liked to play his friends against each o<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>us</strong>ing<strong>on</strong>e as a red flag and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r as a bull. Some thought <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>was even built like a bullfighter, str<strong>on</strong>g and powerful.He did seem massive but was <strong>on</strong>ly five feet two inches tall.Although he never exercised, he was always fit and had un<strong>us</strong>ualstamina. He could stand in fr<strong>on</strong>t of a canvas for seven or eighthours at a stretch. "Work is <strong>the</strong> most important" was his favoritemotto, and he was hugely productive.A master of publicity, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> decided early <strong>on</strong> that <strong>the</strong> amount of m<strong>on</strong>ey a painting sold for was directly related to <strong>the</strong>legend surrounding <strong>the</strong> artist: "It's not what an artist does that counts, but what he is." And so, with his penetrating stareand a lit cigarette c<strong>on</strong>stantly between his lips, he radiated self-c<strong>on</strong>fidence and cultivated a fiery image. He liked to be inabsolute command of every situati<strong>on</strong>.Although <strong>us</strong>ually he got <strong>the</strong> adulati<strong>on</strong> he craved, sometimes it was too much; <strong>on</strong>ce when he was surrounded by a cheeringcrowd, he took out <strong>the</strong> gun he carried whenever he left his studio and fired it into <strong>the</strong> air. Within sec<strong>on</strong>ds <strong>the</strong> area aroundhim was deserted.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> knew every<strong>on</strong>e. He hid in air-raid shelters with <strong>the</strong> writer Gertrude Stein—a l<strong>on</strong>gtime friend—during World WarI and gave her advice when her poodle died. He often walked <strong>the</strong> composer Erik Satie home, doffing his hat and saying,"Good night, Mr. Satie," and he drew a portrait of composer Igor Stravinsky that military authorities were sure was asecret map. Writer Ernest Hemingway came to visit immediately after World War II and brought him a box of handgrenades. Yet he was notorio<strong>us</strong> for cruelty to friends, o<strong>the</strong>r artists, bystanders; it was said that living with him meantwearing armor twenty-four hours a day.Some of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s romantic relati<strong>on</strong>ships were with famo<strong>us</strong> women (<strong>the</strong> ballerina Olga Koklova, <strong>the</strong> painter andphotographer Dora Maar, <strong>the</strong> painter Francoise Gilot), and some were not. He would walk up to a woman and say, "I'm<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>! You and I are going to do great things toge<strong>the</strong>r." He was not good at making decisi<strong>on</strong>s and was sometimesinvolved with two or three women at <strong>the</strong> same time, preferring to let <strong>the</strong> women fight it out. Neighbors didn't alwaysapprove of his lifestyle and at least <strong>on</strong>ce threw st<strong>on</strong>es at his windows in protest. Jacqueline, his sec<strong>on</strong>d and last wife, was<strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly pers<strong>on</strong> he could stand to have around when he painted.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> went to great lengths to entertain his four small children—dressing up in women's underwear, drawing <strong>on</strong>tablecloths, performing magic tricks with paper towels, preparing birthday dinners made up entirely of different kinds ofchocolate desserts. As his children grew older, however, he lost some of his interest in <strong>the</strong>m. His favorite clo<strong>the</strong>s were

5striped sailors' jerseys, baggy tro<strong>us</strong>ers, Turkish slippers, and berets (especially after he started losing his hair). He kepthis wallet in <strong>the</strong> inside pocket of his coat, fastened with a safety pin for extra security; friends were am<strong>us</strong>ed at <strong>the</strong> troublehe had to go to every time he wanted to pay for something. He had certain s<strong>us</strong>pici<strong>on</strong>s—he believed, for example, that ifhis hair clippings fell into <strong>the</strong> wr<strong>on</strong>g hands, <strong>the</strong>y could be <strong>us</strong>ed against him. He didn't like <strong>the</strong> teleph<strong>on</strong>e and didn't get <strong>on</strong>euntil <strong>on</strong>e s<strong>on</strong> almost died when <strong>the</strong> family couldn't call for medical help. He threw nothing away, not even empty cigarettepacks and <strong>the</strong> paper and ribb<strong>on</strong>s from packages. He always locked his studio, and absolutely no <strong>on</strong>e was allowed to d<strong>us</strong>tit.He kept to a diet of fish, vegetables, rice pudding, grapes, raspberries cr<strong>us</strong>hedin milk, large pieces of fresh ginger, carrot and pea soup, and mineral water.His mid-afterno<strong>on</strong> snack was lime-blossom tea and toast.Restless, he moved often. He bought <strong>on</strong>e of his three mansi<strong>on</strong>s in <strong>the</strong> south ofFrance for <strong>the</strong> price commanded by <strong>on</strong>e of his still lifes, which tickled him. In<strong>on</strong>e chateau he covered <strong>the</strong> walls of <strong>the</strong> luxurio<strong>us</strong> bathroom -where his wifewould give him his bath—with wild jungle beasts. In his last villa, Notre-Dame-de-Vie, he was protected by electr<strong>on</strong>ic gates and guard dogs. There washardly any tamable animal he didn't shelter at some point, including am<strong>on</strong>key, Esmeralda <strong>the</strong> goat, reptiles, and numero<strong>us</strong> Afghan hounds. As so<strong>on</strong>as he could afford it he hired a chauffeur: "Driving a car is very bad for apainter's wrists!"<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> might have liked this book, or at least this chapter. After 1945 about six books <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> were published eachyear, and he enjoyed reading <strong>the</strong>m. Knowing that anything he said would eventually show up in <strong>the</strong> papers, he subscribedto a service that clipped articles for him. At <strong>the</strong> public premiere of a documentary about him, he am<strong>us</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> audience bycalling out for a sec<strong>on</strong>d showing –and <strong>the</strong>n a third.Gradually he cut himself off from almost every<strong>on</strong>e except his fans; he even ref<strong>us</strong>ed to meet his grandchildren. At hiseightieth birthday party—for which four tho<strong>us</strong>and invitati<strong>on</strong>s were sent—he arrived escorted by police. He remained vitaland prolific and in his ninetieth year did two hundred paintings. He was still working <strong>the</strong> day he died, two years later, ofheart failure. His last words were to his doctor: "You are wr<strong>on</strong>g not to be married. It's <strong>us</strong>eful."He died without a will, and his estate, valued at hundreds of milli<strong>on</strong>s of dollars, waseventually divided between Jacqueline, three children, and two grandchildren.ARTWORKS<str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s early days of Paris poverty are known as <strong>the</strong> Blue Period beca<strong>us</strong>e everything hepainted—self-portraits, beggars, harlequins, and m<strong>us</strong>icians such as The Old Guitarist(right)—came out sad and blue.Then followed <strong>the</strong> Pink Period, when <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> began his first real romantic relati<strong>on</strong>ship(with a neighbor) and grew happier. Its first picture is c<strong>on</strong>sidered to be The Young Girlwith a Basket of Flowers, bought by Gertrude Stein. Paris papers called ano<strong>the</strong>r PinkPeriod work, Family of Saltimbanques, "grotesque and infamo<strong>us</strong>," but <strong>the</strong> spectacularprice paid for <strong>the</strong> painting of six circ<strong>us</strong> performers changed <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s life.Guernica is <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s resp<strong>on</strong>se to <strong>the</strong> German bombing of a Spanish town by that name,in which sixteen hundred civilians died. During <strong>the</strong> German occupati<strong>on</strong> of Paris duringWorld War II, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> kept a large photo of Guernica <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> wall of his studio. A Naziofficer <strong>on</strong>ce saw it and said, "So it was you who did that," to which <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g> replied, "No,you did it."The model for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s famo<strong>us</strong> peace dove, created for a Peace C<strong>on</strong>gress held after World War 11, was <strong>on</strong>e of Matisse'sbirds. Posters of it were all over Paris when <str<strong>on</strong>g>Picasso</str<strong>on</strong>g>'s daughter was born; he named her Paloma (Spanish for dove).