the middle ages: the reign of religion - Phs.poteau.k12.ok.us

the middle ages: the reign of religion - Phs.poteau.k12.ok.us

the middle ages: the reign of religion - Phs.poteau.k12.ok.us

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

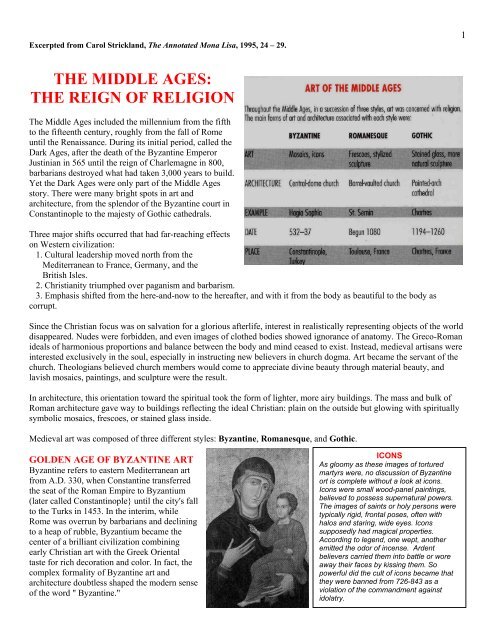

Excerpted from Carol Strickland, The Annotated Mona Lisa, 1995, 24 – 29.1THE MIDDLE AGES:THE REIGN OF RELIGIONThe Middle Ages included <strong>the</strong> millennium from <strong>the</strong> fifthto <strong>the</strong> fifteenth century, roughly from <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> Romeuntil <strong>the</strong> Renaissance. During its initial period, called <strong>the</strong>Dark Ages, after <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Byzantine EmperorJ<strong>us</strong>tinian in 565 until <strong>the</strong> <strong>reign</strong> <strong>of</strong> Charlemagne in 800,barbarians destroyed what had taken 3,000 years to build.Yet <strong>the</strong> Dark Ages were only part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle Agesstory. There were many bright spots in art andarchitecture, from <strong>the</strong> splendor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Byzantine court inConstantinople to <strong>the</strong> majesty <strong>of</strong> Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>drals.Three major shifts occurred that had far-reaching effectson Western civilization:1. Cultural leadership moved north from <strong>the</strong>Mediterranean to France, Germany, and <strong>the</strong>British Isles.2. Christianity triumphed over paganism and barbarism.3. Emphasis shifted from <strong>the</strong> here-and-now to <strong>the</strong> hereafter, and with it from <strong>the</strong> body as beautiful to <strong>the</strong> body ascorrupt.Since <strong>the</strong> Christian foc<strong>us</strong> was on salvation for a glorio<strong>us</strong> afterlife, interest in realistically representing objects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> worlddisappeared. Nudes were forbidden, and even im<strong>ages</strong> <strong>of</strong> clo<strong>the</strong>d bodies showed ignorance <strong>of</strong> anatomy. The Greco-Romanideals <strong>of</strong> harmonio<strong>us</strong> proportions and balance between <strong>the</strong> body and mind ceased to exist. Instead, medieval artisans wereinterested excl<strong>us</strong>ively in <strong>the</strong> soul, especially in instructing new believers in church dogma. Art became <strong>the</strong> servant <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>church. Theologians believed church members would come to appreciate divine beauty through material beauty, andlavish mosaics, paintings, and sculpture were <strong>the</strong> result.In architecture, this orientation toward <strong>the</strong> spiritual took <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> lighter, more airy buildings. The mass and bulk <strong>of</strong>Roman architecture gave way to buildings reflecting <strong>the</strong> ideal Christian: plain on <strong>the</strong> outside but glowing with spirituallysymbolic mosaics, frescoes, or stained glass inside.Medieval art was composed <strong>of</strong> three different styles: Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic.GOLDEN AGE OF BYZANTINE ARTByzantine refers to eastern Mediterranean artfrom A.D. 330, when Constantine transferred<strong>the</strong> seat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Roman Empire to Byzantium(later called Constantinople} until <strong>the</strong> city's fallto <strong>the</strong> Turks in 1453. In <strong>the</strong> interim, whileRome was overrun by barbarians and decliningto a heap <strong>of</strong> rubble, Byzantium became <strong>the</strong>center <strong>of</strong> a brilliant civilization combiningearly Christian art with <strong>the</strong> Greek Orientaltaste for rich decoration and color. In fact, <strong>the</strong>complex formality <strong>of</strong> Byzantine art andarchitecture doubtless shaped <strong>the</strong> modern sense<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> word " Byzantine."ICONSAs gloomy as <strong>the</strong>se im<strong>ages</strong> <strong>of</strong> torturedmartyrs were, no disc<strong>us</strong>sion <strong>of</strong> Byzantineort is complete without a look at icons.Icons were small wood-panel paintings,believed to possess supernatural powers.The im<strong>ages</strong> <strong>of</strong> saints or holy persons weretypically rigid, frontal poses, <strong>of</strong>ten withhalos and staring, wide eyes. Iconssupposedly had magical properties.According to legend, one wept, ano<strong>the</strong>remitted <strong>the</strong> odor <strong>of</strong> incense. Ardentbelievers carried <strong>the</strong>m into battle or woreaway <strong>the</strong>ir faces by kissing <strong>the</strong>m. Sopowerful did <strong>the</strong> cult <strong>of</strong> icons became that<strong>the</strong>y were banned from 726-843 as aviolation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> commandment againstidolatry.

2MOSAICS. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world's greatest art, in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong>mosaics, was created during <strong>the</strong> fifth and sixth centuries inTurkish Byzantium and its Italian capital, Ravenna. Mosaicswere intended to publicize <strong>the</strong> now-<strong>of</strong>ficial Christian creed,so <strong>the</strong>ir subject was generally <strong>religion</strong> with Christ shown asteacher and all-powerful ruler. Sumptuo<strong>us</strong> grandeur, withhalos spotlighting sacred figures and shimmering goldbackgrounds, characterized <strong>the</strong>se works.Human figures were flat, stiff, and symmetrically placed,seeming to float as if hung from pegs. Artisans had nointerest in suggesting perspective or volume. Tall, slimhuman figures with almond-shaped faces, huge eyes, andsolemn expressions gazed straight ahead, without <strong>the</strong> leasthint <strong>of</strong> movement.“J<strong>us</strong>tinian and Attendants,” c. 547, San Vitale, RavennaHAGIA SOPHIA. When Emperor J<strong>us</strong>tinian decided to build a church inConstantinople, <strong>the</strong> greatest city in <strong>the</strong> world for 400 years, he wanted tomake it as grand as his empire. He assigned <strong>the</strong> task to two ma<strong>the</strong>maticians,An<strong>the</strong>mi<strong>us</strong> <strong>of</strong> Tralles and Isidor<strong>us</strong> <strong>of</strong> Milet<strong>us</strong>. They obliged his ambition witha completely innovative structure, recognized as a climax in Byzantinearchitectural style.The Hagia Sophia (pronounced HAH zhee ah soh FEE ah; <strong>the</strong> name means"holy wisdom") merged <strong>the</strong> vast scale <strong>of</strong> Roman buildings like <strong>the</strong> Baths <strong>of</strong>Caracals with an Eastern mystical atmosphere. Nearly three football fieldslong, it combined <strong>the</strong> Roman rectangular basilica layout with a huge centraldome. Architects achieved this breakthrough thanks to <strong>the</strong> Byzantinecontribution to engineering—pendentives. For <strong>the</strong> first time, four archesforming a square (as opposed to round weight-bearing walls, as in <strong>the</strong>Pan<strong>the</strong>on) supported a dome. This structural revolution accounted for <strong>the</strong>l<strong>of</strong>ty, unobstructed interior with its soaring dome.An<strong>the</strong>mi<strong>us</strong> <strong>of</strong> Tralles and Isidor<strong>us</strong> <strong>of</strong>Milet<strong>us</strong>, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople(Istanbul, Turkey), 532-37. Ca<strong>the</strong>dralsfrom Venice to R<strong>us</strong>sia were based onthis darned structure, a masterpiece<strong>of</strong> Byzantine architecture.Forty arched windows encircle <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dome, creating <strong>the</strong> ill<strong>us</strong>ion thatit rests on a halo <strong>of</strong> light. This overhead radiance seems to dissolve <strong>the</strong> wallsin divine light, transforming <strong>the</strong> material into an o<strong>the</strong>rworldly vision. Sosuccessful was his creation, that J<strong>us</strong>tinian boasted, "Solomon, I havevanquished <strong>the</strong>e! "

3ROMANESQUE ART: STORIES IN STONEWith <strong>the</strong> Roman Catholic faith firmly established, a wave <strong>of</strong> church construction throughout feudal Europe occurred from1050 to 1200. Builders borrowed elements from Roman architecture, such as rounded arches and columns, giving rise to<strong>the</strong> term Romanesque for <strong>the</strong> art and architecture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> period. Yet beca<strong>us</strong>e Roman buildings were timber-ro<strong>of</strong>ed andprone to fires, medieval artisans began to ro<strong>of</strong> churches with stone vaulting. In this system, barrel or groin vaults restingon piers could span large openings with few internal supports or obstructions.Pilgrim<strong>ages</strong> were in vogue at <strong>the</strong> time, and church architecture took into account <strong>the</strong> hordes <strong>of</strong> tourists visiting shrines <strong>of</strong>sacred bones, garments, or splinters from <strong>the</strong> True Cross brought back by <strong>the</strong> Cr<strong>us</strong>aders. The layout was cruciform,symbolizing <strong>the</strong> body <strong>of</strong> Christ on <strong>the</strong> cross with a long nave transversed by a shorter transept. Arcades allowed pilgrimsto walk around peripheral aisles without disrupting ceremonies for local worshipers in <strong>the</strong> central nave. At <strong>the</strong> chevet("pillow" in French), called such beca<strong>us</strong>e it was conceived as <strong>the</strong> resting place for Christ's head as he hung on <strong>the</strong> cross,behind <strong>the</strong> altar, were semicircular chapels with saints' relics.The exterior <strong>of</strong> Romanesque churches was ra<strong>the</strong>r plain except for sculptural relief around <strong>the</strong> main portal. Since mostchurch-goers were illiterate, sculpture taught religio<strong>us</strong> doctrine by telling stories in stone. Sculpture was concentrated in<strong>the</strong> tympanum, <strong>the</strong> semicircular space beneath <strong>the</strong> arch and above <strong>the</strong> lintel <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> central door. Scenes <strong>of</strong> Christ'sascension to <strong>the</strong> heavenly throne were popular, as well as grisly Last Judgment dioramas, where demons gobbled haplesssouls, while devils strangled or spitted naked bodies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> damned.GIOTTO: PIONEER PAINTERBeca<strong>us</strong>e Italy maintained contact with Byzantine civilization, <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong>painting was never abandoned. But at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 13th century, a flowering<strong>of</strong> technically skilled painting occurred, with masters like Duccio and SimoneMartini <strong>of</strong> Siena and Cimabue and Giotto <strong>of</strong> Florence breaking with <strong>the</strong> frozenByzantine style for s<strong>of</strong>ter, more lifelike forms. The frescoes (paintings ondamp plaster walls) <strong>of</strong> Giotto di Bondone (pronounced JOT toe; c.1266-1337)were <strong>the</strong> first since <strong>the</strong> Roman period to render human forms suggestingweight and roundness. They marked <strong>the</strong> advent <strong>of</strong> what would afterwardbecome painting's central role in Western art.Giotto, “Noli me tangere,” 1305, fresco, Arena Chapel, Padua. Giotto paintedhuman figures with a sense <strong>of</strong> anatomical structure beneath <strong>the</strong> drapery.

4ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS. With hordes <strong>of</strong> pillagers looting and razingcities <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> former Roman Empire, monasteries were all that stood betweenWestern Europe and total chaos. Here monks and nuns copied man<strong>us</strong>cripts,keeping alive both <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> ill<strong>us</strong>tration in particular and Western civilization ingeneral. By this time, <strong>the</strong> papyr<strong>us</strong> scroll <strong>us</strong>ed from Egypt to Rome was replacedby <strong>the</strong> vellum (calfskin) or parchment (lambskin) codex, made <strong>of</strong> separate p<strong>ages</strong>bound at one side. Man<strong>us</strong>cripts were considered sacred objects containing <strong>the</strong>word <strong>of</strong> God. They were decorated lavishly, so <strong>the</strong>ir outward beauty wouldreflect <strong>the</strong>ir sublime contents. Covers were made <strong>of</strong> gold studded with precio<strong>us</strong>and semiprecio<strong>us</strong> gems. Until printing was developed in <strong>the</strong> fifteenth century,<strong>the</strong>se man<strong>us</strong>cripts were <strong>the</strong> only form <strong>of</strong> books in existence, preserving not onlyreligio<strong>us</strong> teachings but also Classical literature.Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> richest, purely ornamental drawings ever produced are contained in<strong>the</strong> illuminated Gospel called <strong>the</strong> Book <strong>of</strong> Kells (760-820), collection <strong>of</strong> TrinityCollege, Dublin, produced by Irish monks. The text was highly embellishedwith colorful abstract patterns. Enormo<strong>us</strong> letters, sometimes composed <strong>of</strong>interlacing whorls and fantastic animal imagery, cover entire p<strong>ages</strong>.

GOTHIC ART: HEIGHT AND LIGHTThe pinnacle <strong>of</strong> Middle Ages artistic achievement, rivaling <strong>the</strong> wonders <strong>of</strong> ancientGreece and Rome, was <strong>the</strong> Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>dral. In fact, <strong>the</strong>se "stone Bibles" evensurpassed Classical architecture in terms <strong>of</strong> technological daring. From 1200 to1500, medieval builders erected <strong>the</strong>se intricate structures, with soaring interiorsunprecedented in world architecture.5What made <strong>the</strong> Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>dral possible were two engineering break-throughs:ribbed vaulting and external supports called flying buttresses. Applying such pointsupports where necessary allowed builders to forgo solid walls pierced by narrowwindows for skeletal walls with huge stained glass windows flooding <strong>the</strong> interiorwith light. Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>drals acknowledged no Dark Ages. Their evolution was acontinuo<strong>us</strong> expansion <strong>of</strong> light, until finally walls were so perforated as to be almostmullions framing immense fields <strong>of</strong> colored, story-telling glass.In addition to <strong>the</strong> latticelike quality <strong>of</strong> Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>dral walls (with an effect like"petrified lace," as <strong>the</strong> writer William Faulkner said), verticality characterizedGothic architecture. Builders <strong>us</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> pointed arch, which increased both <strong>the</strong> realityand ill<strong>us</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> greater height. Architects vied for <strong>the</strong> highest naves (at Amiens, <strong>the</strong>nave reached an extreme height <strong>of</strong> 144 feet). When, as <strong>of</strong>ten happened, ambitionoutstripped technical skill and <strong>the</strong> naves collapsed, church members tirelesslyrebuilt <strong>the</strong>m.Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>drals were such a symbol <strong>of</strong> civic pride that an invader's worst insultwas to pull down <strong>the</strong> tower <strong>of</strong> a conquered town's ca<strong>the</strong>dral. Communal devotion to<strong>the</strong> buildings was so intense that all segments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population participated inconstruction. Lords and ladies, in worshipful silence, worked alongside butchers andmasons, dragging carts loaded with stone from quarries. Buildings were so elaboratethat construction literally took <strong>ages</strong>—six centuries for Cologne Ca<strong>the</strong>dral—whichexplains why some seem a hodge-podge <strong>of</strong> successive styles.

THE ART OF ARCHITECTURE. Medieval <strong>the</strong>ologiansbelieved a church's beauty would inspire parishioners to meditation and belief.As a result, churches were much more than j<strong>us</strong>t assembly halls. They weretexts, with volumes <strong>of</strong> ornaments preaching <strong>the</strong> path to salvation. The chiefforms <strong>of</strong> inspirational decoration in Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>drals were sculpture, stainedglass, and tapestries.SCULPTURE: LONG AND LEAN. Ca<strong>the</strong>dral exteriors displayed carvedBiblical tales. The Early Gothic sculptures <strong>of</strong> Chartres (pronounced shartr)and <strong>the</strong> High Gothic stone figures <strong>of</strong> Reims (pronounced ranz) Ca<strong>the</strong>dralshow <strong>the</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong> medieval art.Jambstatues,RoyalPortals,ChartresCa<strong>the</strong>dral,1145-706The Chartres figures <strong>of</strong> Old Testament kings and queens (1140-50) are pillarpeople, elongated to fit <strong>the</strong> narrow columns that ho<strong>us</strong>e <strong>the</strong>m. Drapery lines areas thin and straight as <strong>the</strong> bodies, with few traces <strong>of</strong> naturalism. By <strong>the</strong> time<strong>the</strong> jamb figures <strong>of</strong> Reims were carved, around 1225-90, sculptors for <strong>the</strong> firsttime since antiquity approached sculpture in-<strong>the</strong>-round. These figures arealmost detached from <strong>the</strong>ir architectural background, standing out from <strong>the</strong>column on pedestals. After <strong>the</strong> writings <strong>of</strong> Aristotle were discovered, <strong>the</strong> bodywas no longer despised but viewed as <strong>the</strong> envelope <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> soul, so artists onceagain depicted flesh naturally."The Visitation," jambstatues <strong>of</strong> west facade,Reims Ca<strong>the</strong>dral, c1225-90, France.Sculpture developedfrom stiff; disproportionatelylong figures(above) to a morerounded, natural style.In "The Visitation," both <strong>the</strong> Virgin Mary and her kinswoman, Elizabeth, lean primarily on one leg, <strong>the</strong>ir upper bodiesturned toward each o<strong>the</strong>r. The older Elizabeth has a wrinkled face, full <strong>of</strong> character, and drapery is handled with moreimagination than before.Rose window, ChartresCa<strong>the</strong>dral, 13th century.Tho<strong>us</strong>ands <strong>of</strong> pieces <strong>of</strong>glass, tinted withchemicals like cobaltand manganese, werebound toge<strong>the</strong>r withstrips <strong>of</strong> lead, whichalso outlinedcomponent figures.STAINED GLASS. Chartres Ca<strong>the</strong>dral was <strong>the</strong> visible soul <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Middle Ages. Built to ho<strong>us</strong>e <strong>the</strong> veil <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Virgin given to<strong>the</strong> city by Charlemagne's grandson, Charles <strong>the</strong> Bald, in 876,it is a multi-media masterpiece. Its stained glass windows, <strong>the</strong>most intact collection <strong>of</strong> medieval glass in <strong>the</strong> world, measure26,900 feet in total area. Ill<strong>us</strong>trating <strong>the</strong> Bible, <strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong>saints, even traditional crafts <strong>of</strong> France, <strong>the</strong> windows are like agigantic, glowing, illuminated man<strong>us</strong>cript.TAPESTRY. Weavers in <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages created highly refined tapestries, minutelydetailed with scenes <strong>of</strong> contemporary life. Large wool-and-silk hangings, <strong>us</strong>ed to cutdrafts, decorated stone walls in chatea<strong>us</strong> and churches. Huge-scale paintings wereplaced behind <strong>the</strong> warp (or lengthwise threads) <strong>of</strong> a loom in order to imitate <strong>the</strong> designin cloth.A series <strong>of</strong> seven tapestries represents <strong>the</strong> unicorn legend. According to popularbelief, <strong>the</strong> only way to catch this mythical beast was to <strong>us</strong>e a virgin sitting in <strong>the</strong> forestas bait. The tr<strong>us</strong>ting unicorn would go to sleep with his head in her lap and awakencaged. The captured unicorn is chained to a pomegranate tree, a symbol <strong>of</strong> bothfertility and, beca<strong>us</strong>e it contained many seeds within one fruit, <strong>the</strong> church. During <strong>the</strong>Renaissance, <strong>the</strong> unicorn was linked with courtly love, but in <strong>the</strong> tapestry's ambiguo<strong>us</strong>depiction both lying down and rearing up, he symbolizes <strong>the</strong> resurrected Christ.“The Unicorn in Captivity,”c. 1500, The Cloisters,MMA, NY.