Download sample chapter - Palgrave

Download sample chapter - Palgrave

Download sample chapter - Palgrave

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

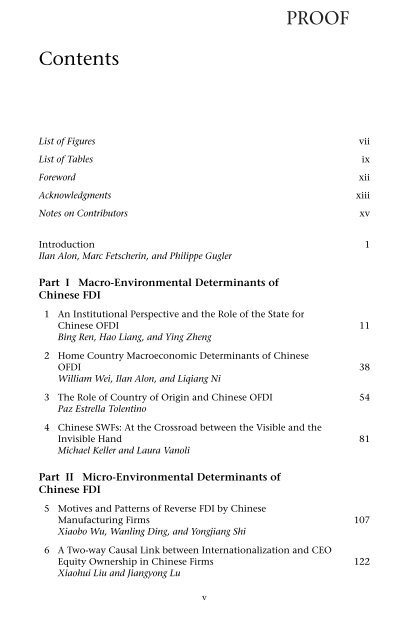

Contents<br />

List of Figures vii<br />

ListofTables ix<br />

Foreword xii<br />

Acknowledgments xiii<br />

Notes on Contributors xv<br />

Introduction 1<br />

Ilan Alon, Marc Fetscherin, and Philippe Gugler<br />

Part I Macro-Environmental Determinants of<br />

Chinese FDI<br />

1 An Institutional Perspective and the Role of the State for<br />

Chinese OFDI 11<br />

Bing Ren, Hao Liang, and Ying Zheng<br />

2 Home Country Macroeconomic Determinants of Chinese<br />

OFDI 38<br />

William Wei, Ilan Alon, and Liqiang Ni<br />

3 The Role of Country of Origin and Chinese OFDI 54<br />

Paz Estrella Tolentino<br />

4 Chinese SWFs: At the Crossroad between the Visible and the<br />

Invisible Hand 81<br />

Michael Keller and Laura Vanoli<br />

Part II Micro-Environmental Determinants of<br />

Chinese FDI<br />

5 Motives and Patterns of Reverse FDI by Chinese<br />

Manufacturing Firms 107<br />

Xiaobo Wu, Wanling Ding, and Yongjiang Shi<br />

6 A Two-way Causal Link between Internationalization and CEO<br />

Equity Ownership in Chinese Firms 122<br />

Xiaohui Liu and Jiangyong Lu<br />

v<br />

PROOF

vi Contents<br />

7 Effects of Absorptive Capacity on International Acquisitions<br />

of Chinese Firms 137<br />

Ping Deng<br />

Part III Chinese FDI in Europe and North America<br />

8 Push and Pull Factors for Chinese OFDI in Europe 157<br />

Yun Schüler-Zhou, Margot Schüller, and Magnus Brod<br />

9 The Rise of Chinese OFDI in Europe 175<br />

Jan Knoerich<br />

10 Chinese M&A in Germany 212<br />

Yipeng Liu and Michael Woywode<br />

11 Chinese SMEs in Prato, Italy 234<br />

Anja Fladrich<br />

12 Chinese State-Controlled Funds and Entities in Canada 257<br />

Xiaohua Lin and Qianyu Chen<br />

Part IV Chinese FDI in Africa<br />

13 Chinese OFDI in Africa: Trends, Prospects, and Threats 279<br />

Gayle Allard<br />

14 Chinese OFDI in Sub-Saharan Africa 300<br />

Raphael Kaplinsky and Mike Morris<br />

Part V Cases of Chinese FDI<br />

PROOF<br />

15 The Case of Florida Splendid China 329<br />

Wenxian Zhang<br />

16 Benelli and Q J Compete in the International Motorbike Arena 355<br />

Francesca Spigarelli, William Wei, and Ilan Alon<br />

17 Geely’s Internationalization and Volvo’s Acquisition 376<br />

Marc Fetscherin and Paul Beuttenmuller<br />

Final Reflections 391<br />

Ilan Alon, Marc Fetscherin, and Philippe Gugler<br />

Author Index 396<br />

Subject Index 405

1<br />

An Institutional Perspective<br />

and the Role of the State for<br />

Chinese OFDI<br />

Bing Ren, Hao Liang, and Ying Zheng<br />

Napoleon called China a ‘sleeping dragon’, but recent economic<br />

developments as China enters the twenty-first century show that the dragon<br />

is awakening. China has maintained strong economic growth since 1979<br />

and sustained a GDP increase of more than 9 percent over the years. The<br />

total volume of economic output increased from 2.8 percent in 1970 to<br />

7.23 percent in 2008, ranking China as the third largest economy in the<br />

world (United Nation Statistics Division Statistical Databases).<br />

China launched its ‘Go Global’ policy in 1999 to encourage highperforming<br />

Chinese firms to invest abroad and upgrade their global competence.<br />

Since then, outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) flows reached<br />

US$55.91 billion in 2008, equal to the FDI inflow in 2003. The annual<br />

growth rate of OFDI averaged 65.7 percent from 2002 to 2008 (Ministry<br />

of Commerce of China). OFDI flows via mergers and acquisitions (M&As)<br />

accounted for 54 percent of the total volume of OFDI (US$30.2 billion) and<br />

an annual increase rate of 379 percent (from 2002 to 2008). China’s OFDI<br />

volume reached USD52.15 billion in 2009 (excluding Hong Kong, Macao,<br />

and Taiwan), equaling 3 percent of global OFDI (World Investment Report,<br />

2009).<br />

How are Chinese firms able to ‘go global’ so quickly – given their relatively<br />

weaker competencies in technological know-how and management skills<br />

and weak ability in integrating global value chains (Deng, 2004; Sun, Peng,<br />

Ren, & Yan, 2010)? According to multinational enterprise (MNE) theories<br />

based on Western firms, such as the Ownership-Location-Internalization<br />

(OLI) paradigm (Dunning, 1980, 1993), it is difficult to explain why this<br />

aggressive international expansion by Chinese firms works so well despite<br />

weaker firm-specific ownership advantage. We also note that China’s international<br />

expansion is largely undertaken by state-owned enterprises (SOEs).<br />

State policies have played a key role in pushing Chinese firms to go abroad,<br />

which poses a challenge to existing MNE and FDI theories (Dunning &<br />

Lundan, 2008; Sun et al., 2010).<br />

11<br />

PROOF

12 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

To answer these questions one must examine the driving forces of Chinese<br />

firms’ internationalization, especially the institutional forces and the role of<br />

the state that the literature has not yet explored. As China’s economic development<br />

involves a high degree of state involvement, it constitutes a unique<br />

institutional foundation that shapes OFDI trajectories at the level of both<br />

the country and the firm. Integrating the recent literature on how formal<br />

and informal institutions such as state policies and national pride influence<br />

the OFDI of emerging market enterprises (EMEs) (e.g., Buckley, Clegg,<br />

Cross, Lin, Voss, & Zheng, 2007; Buckley, Cross, Tan, Liu, & Voss, 2008; Luo,<br />

Xue, & Han, 2010; Hope, Thomas, & Vyas, 2011), we argue that the fast<br />

growth of China’s OFDI is a consequence of the state’s involvement and<br />

formal and informal institutional motivating forces. We define the formal<br />

institutional drivers as governmental policy, the bureaucratic administrative<br />

system, and the government ownership arrangement in firms. Informal<br />

institutions include the state ideology and national pride (Hope et al., 2010).<br />

Driven by these institutions, Chinese firms are highly motivated to conduct<br />

OFDI for country-level political and economic objectives, or for firm-level<br />

global competence.<br />

The importance of this study is as follows. Most studies on international<br />

business have focused on OFDI by mature market enterprises through studying<br />

the motivations, processes, and outcomes of their internationalization<br />

(Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Hennart, 1982; Dunning, 1988; Dore, 1990).<br />

More recent studies explore the motivations for internationalization of EMEs<br />

(Luo & Tung, 2007; Witt & Lewin, 2007; Rui & Yip, 2008). However, except<br />

for a few studies (e.g., Buckley et al., 2008; Luo et al., 2010), the role of<br />

the state in the OFDI of EMEs is largely ignored. Similarly, among the studies<br />

emphasizing the institutional perspective of EMEs’ internationalization,<br />

there is no in-depth discussion of how macro-level institutional foundations<br />

shaped by the state could influence micro-level firm strategic choices. Our<br />

study helps fill these gaps by analyzing the specific roles of the state and<br />

the broader economic and social contexts that may influence how the state<br />

performs its role. We also analyze how these state institutions might become<br />

sources of comparative ownership advantages and help shape Chinese firms’<br />

OFDI trajectories.<br />

The remainder of the <strong>chapter</strong> is organized as follows. Section 1 reviews<br />

the literature. In Section 2 we analyze the role of the state and the formal<br />

and informal institutions by looking at their influence on Chinese firms’<br />

OFDI motivations and strategies. We also discuss contingency views of our<br />

theoretical propositions and provide our conclusions.<br />

1. Literature review<br />

PROOF<br />

1.1. Motivations for OFDI<br />

There is a vast literature examining the motivations for FDI (see Meyer &<br />

Nguyen [2005] for a survey). The theory of capital movements suggests that

PROOF<br />

Bing Ren et al. 13<br />

FDI is a part of the firm’s portfolio investments (Iversen, 1935; Aliber, 1971).<br />

Hymer (1960), Kogut and Zander (1993) argue that FDI is a means of transferring<br />

knowledge and other tangible and intangible firm assets to organize<br />

production overseas. Vernon (1966) uses the concept of product lifecycle<br />

to theorize that firms set up production facilities abroad for standardized<br />

mature products in their home markets. Other literature sees FDI as a motive<br />

for risk diversification (Rugman, 1981) and a bandwagon effect exhibited by<br />

MNEs when they follow their rivals into new markets as a strategic response<br />

to oligopolistic rivalry (Knickerbocker, 1973).<br />

The international business (IB) literature, especially Dunning’s OLI<br />

paradigm, sees OFDI as a primary means by which firms can appropriate<br />

rents in overseas markets by exploiting their idiosyncratic resources<br />

and capabilities (Dunning, 1958; Caves, 1971). The internalization theory<br />

(McManus, 1972; Buckley & Casson, 1976; Rugman, 1981; Hennart,<br />

1982) sees OFDI as a way to reduce the transaction costs associated<br />

with coordinating activities across national boundaries, while the resourcebased<br />

view (Lippman & Rumelt, 1982; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Teece,<br />

Pisano, & Shuen, 1997) argues that firms enter foreign markets to create<br />

value. The literature suggests that the OFDI of EMEs is different from<br />

that of enterprises from developed economies (e.g., Makino, Lau, & Yeh,<br />

2002).<br />

Studies on comparative ownership and governance suggest that the<br />

unique mode of governance and control in emerging economies is particularly<br />

important in determining the OFDI decision (Claessens, Djankov, &<br />

Lang, 2000; Filatotchev, Strange, Piesse, & Lien, 2007). Other studies on<br />

EME international strategy emphasize the institutional perspective (e.g.,<br />

Tihanyi, Griffith, & Russell, 2005; Witt & Lewin, 2007; Dunning & Lundan,<br />

2008; Peng, Wang, & Jiang, 2008; Seyoum, 2009; Ge & Ding, 2011), suggesting<br />

that institutions, both formal and informal, influence EME OFDI<br />

behavior – either through positive or negative effects (Luo & Tung, 2007;<br />

Witt & Lewin, 2007). Formal institutions, such as policy, influence EME outward<br />

investment: this has been manifested in the home and host country<br />

markets (e.g., Loree & Guisinger, 1995; Lien, Piesse, Strange, & Filatotchev,<br />

2005; Buckley et al., 2008; Seyoum, 2009; Luo et al., 2010). Informal institutions<br />

may determine OFDI flows and strategies such as choice of location<br />

and entry mode (Buckley et al., 2007; Elango & Pattnaik, 2007; Yiu, Lau,<br />

& Bruton, 2007; Lu & Ma, 2008). Examples include institutional distance<br />

or cultural proximity between the home and host country markets (e.g.,<br />

Buckley et al., 2007; Seyoum, 2009), and host and home country business<br />

networks. Formal and informal institutions together may influence<br />

OFDI strategy in a more dynamic way (Dunning & Lundan, 2008; Peng et al.,<br />

2008).<br />

Chinese firms that invest abroad, especially large multinationals, are<br />

typically state-owned or state-controlled. Recent studies on Chinese and<br />

Indian multinational cross-border M&As reveal that SOEs constitute a bigger

14 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

proportion among the main players conducting cross-border M&As in China<br />

thaninIndia(Sunet al., 2010). As China’s global push accelerates, many<br />

observers believe that institutional factors should act as advantages for generating<br />

more aggressive OFDI activities (Luo et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2010),<br />

which is usually not the case for mature market economies (Dunning, 1988;<br />

Gomes-Casseres, 1990; Hennart & Park, 1994). Many even suggest that<br />

Chinese firms’ OFDI is to a large extent designed to follow the state’s policy<br />

guidance, especially now (Child & Rodrigues, 2005; Buckley et al., 2007;<br />

Boisot & Meyer, 2008; Deng, 2009; Sutherland, 2009; Yao & Sutherland,<br />

2009; Luo et al., 2010). Chinese OFDI trajectories are likely shaped by<br />

the specific institutional regime developed under the state, although little<br />

research on the topic exists.<br />

2. Framework<br />

PROOF<br />

2.1. The role of the state<br />

To some extent, China is still a state-controlled political economy where the<br />

state plays a dominant role in driving economic transactions and performance<br />

(Chang, 1994; Deng, 2004; Dunning & Pitelis, 2009; Huang, 2010;<br />

Nee, 2010). The state designs and influences formal institutions and regulates<br />

economic and business activities through the formal policy at the<br />

central and local government levels. The state also establishes the administrative<br />

system and arranges government ownership within various industrial<br />

sectors. The state helps shape informal institutional frameworks such as<br />

firm–government relationships, political connections and inter-bureau or<br />

inter-firm network ties that influence business behavior (Peng & Heath,<br />

1996; Xin & Peace, 1996; Keister, 1998; Yiu et al., 2007). The rise of China<br />

on the global political and economic stage cultivates the role of the state in<br />

shaping China’s national pride and ideology.<br />

The state’s role is even more significant when considering the wider economic<br />

and social context into which China has stepped. China is now facing<br />

both external and internal pressure to develop better and stronger economic<br />

and social systems. Internally, the state faces pressure to enhance national<br />

wealth. Although the economy has sustained a high growth rate in the past<br />

several decades, the government is yet not sure about the sustainability of<br />

future growth. Externally, China’s economy and society now depend heavily<br />

on other economies and societies, for more successful participation in the<br />

global economic and social stage.<br />

The Chinese state has aimed to develop both hard and soft power for<br />

coping with these challenges and to construct long-term development<br />

goals (‘The Economic Observer’ [in Chinese], May 31, 2010). The state has<br />

tried to maintain strategic control over national-level formal and informal<br />

institutional development.

PROOF<br />

Bing Ren et al. 15<br />

2.2. Formal institutional regime<br />

Policy<br />

The Chinese government has, to a great extent, played a crucial role in shaping<br />

the structure of China’s approved outward investment through external<br />

policy influence. However, the OFDI policies went through an evolutionary<br />

process. According to Luo et al. (2010) and others such as Buckley et al.<br />

(2008), Chinese OFDI policies moved through three major phases: the initiation<br />

of OFDI policy; the enrichment of the institutional frameworks; and<br />

setting up ‘going global’ as a country-level strategy.<br />

In Phase 1 (1979–1990), the Chinese state played a key role in initiating<br />

the OFDI policies. In 1979, with the launch of the ‘open door’ policy<br />

by Deng Xiaoping, the State Council came up with the concept of ‘setting<br />

up enterprises overseas’ (Zhao, 2007, p. 56). The state issued concrete<br />

policies and principles to guide OFDI. In 1984, the Ministry of Foreign<br />

Trade and Economic Cooperation (MFTEC, today’s MOC) released the first<br />

regulations on OFDI, called ‘Circular concerning approval authorities and<br />

administrative principles for opening up non-trade joint venture overseas’.<br />

The State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) also published the first<br />

regulations on administration of foreign exchange: ‘Measures for foreign<br />

exchange control relating to overseas investment’ (1989). Since then, a primary<br />

structure of policy and administration of OFDI was established. During<br />

this period, the Chinese government was perceived as taking the plunge in<br />

OFDI activities.<br />

In Phase 2 (1991–2000), the Chinese state enriched the institutional<br />

framework of OFDI policy. On 12 October 1992, Jiang Zemin, the representative<br />

of third-generation leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, gave a<br />

report to the Fourteen Chinese Communist National Congress, emphasizing<br />

the deepening of reform and opening up policy to ‘expand OFDI and multinational<br />

operations of Chinese enterprises’ (Jiang, 1992). Following Jiang’s<br />

talk, more specific and detailed provisions were added to formulate the regulatory<br />

and administrative system on firms’ OFDI activities. For example, the<br />

Administration of Overseas Investment Projects (National Planning Commission<br />

[NPC], March 1991) normalized the approval procedure and gave<br />

more specific requirements for OFDI.<br />

In Phase 3 (2001–present), the state set the ‘Going Global’ policy as a<br />

country-level strategy to enhance competitive advantages through OFDI<br />

strategies. The Chinese government initiated the ‘going abroad’ policy<br />

as country-level strategy in 2000. (This was reflected in ‘Suggestion on<br />

Constructing the 10th Five Year Plan for National Economic and Social<br />

Development’.)<br />

In 2003, the State Development and Reform Commission (SDRC) specified<br />

the boundaries for key OFDI projects, including: (1) seeking natural<br />

resources in areas where China is lacking; (2) investing in manufacturing

16 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

PROOF<br />

that promotes export of technologies, products, and equipment; (3) setting<br />

up R&D collaborative projects which could bring in advanced technologies,<br />

managerial experience, and specialized talents; (4) conducting M&As to<br />

increase international competitiveness and market exploration of firms.<br />

The Chinese government encouraged firms to pursue the above projects to<br />

upgrade firm-level competence.<br />

In the meantime, joining the World Trade Organization demanded a<br />

higher level of openness, and this also encouraged the Chinese government<br />

to modify the existing strict policies to create a friendlier institutional environment<br />

for OFDI. For example, the central state deregulated investment<br />

approval and foreign exchange controls. The government provided support<br />

for finance, credit, and insurance (Enterprise Institute of Development<br />

Research Center of the State Council, 2006) and strengthened supervision<br />

of multinational operating performance to monitor the effectiveness of the<br />

‘go global policy’. Table 1.1 provides a detailed illustration of major policies<br />

released by the state on Chinese firms’ OFDI.<br />

Five important institutional elements are particularly emphasized by the<br />

state and successfully advanced the OFDI of Chinese firms. The first institutional<br />

element refers to the approval process. The state streamlined the<br />

approval procedure and decentralized approval authority for OFDI. The state<br />

relaxed foreign exchange control gradually, especially in the examination of<br />

capital resource and exchange risks. In providing concrete investment support,<br />

the state supported investment projects for credit, capital, information,<br />

subsidies, and tax collection. The state also aimed to set up more efficient<br />

supervision mechanisms on post-investment performance of OFDI enterprises.<br />

Lastly, the state has been seeking better international protection for<br />

firms’ overseas investment through setting up bilateral investment treaties<br />

and multilateral and regional protection mechanisms (for more straightforward<br />

descriptions of the five institutions’ evolution, see Figures 1.1a–1.1e).<br />

Bureaucratic administration<br />

Bureaucratic administration policy is usually made by important players in<br />

particular bureaucratic systems, and important operating systems are also<br />

implemented by the administrators to utilize the policy effect. In general,<br />

the bureaucratic administration related to Chinese OFDI is complex due to<br />

the multiple bureaucratic players involved in decision-making, regulation<br />

and, supervision for OFDI. In the bureaucratic administration system, the<br />

first layer is the State Council, which plans China’s overall OFDI for the long<br />

term. Under the leadership of the State Council, the State Development and<br />

Reform Commission (SDRC, formerly the National Planning Commission)<br />

is the major institution of the second layer responsible for studying and<br />

advancing strategies and plans for OFDI, and examining the optimization of<br />

the policies. Guided by the strategic plan of the SDRC, the Department of

Table 1.1 The policy regime of China’s OFDI<br />

Examination<br />

and<br />

approval<br />

Key policy Key point<br />

Approval Authorities and<br />

Administrative Principles<br />

for Opening up Non-trade<br />

Joint Venture Overseas<br />

(MFTEC, May 1984)<br />

Approval Procedures for<br />

Setting up Overseas<br />

Subsidiaries (MFTEC, July<br />

1985)<br />

Administration and<br />

Approval of Establishing<br />

Non-trade Enterprises<br />

Overseas (MFTEC, July<br />

1985)<br />

Administration of<br />

Overseas Investment<br />

Projects (NPC, March<br />

1991)<br />

Verification and Approval<br />

Procedures for<br />

OFDI (SNRC, October<br />

2004)<br />

Examination and<br />

Approval of Investment to<br />

Run Enterprises Overseas<br />

(MOC, October 2004)<br />

PROOF<br />

17<br />

1. Authorize MFTEC to approve OFDI;<br />

prior to this, all OFDI has to be<br />

approved by State Council<br />

2. Major projects concerning resource<br />

and projects exceeding<br />

US$10 million to be approved by<br />

State Council<br />

3. Projects concerning state property to<br />

be approved by NPC and METEC<br />

Opens OFDI for all economic entities<br />

with financial resources, foreign<br />

joint venture partners, and relevant<br />

capabilities<br />

1. Approval result should be handed<br />

down in no more than 3 months<br />

2. Chinese OFDI should focus on using<br />

overseas technologies, resources, and<br />

markets<br />

1. Projects exceeding 1 million to be<br />

approved by NPC, exceeding<br />

30 million to be approved by the<br />

State Council.<br />

2. Projects concerning state-owned<br />

assets must be approved by State<br />

Council<br />

3. Project proposals, feasibility reports,<br />

corporate contracts, and articles<br />

should be provided by OFDI<br />

enterprises<br />

4. Approval result should be handed<br />

down in no more than 60 days<br />

1. Projects exceeding US$10 million to<br />

be approved by SNRC (except<br />

projects concerning resources),<br />

exceeding US$50 million approved<br />

by State Council<br />

2. Approval result should be handed<br />

down in no more than 20 days<br />

1. All companies are permitted to run<br />

enterprises overseas<br />

2. Project proposals, feasibility reports<br />

are substituted by project application<br />

3. Approval result should be handed<br />

down in no more than 15 days

18<br />

Table 1.1 (Continued)<br />

Foreign<br />

exchange<br />

control<br />

Key policy Key point<br />

Administration of<br />

OFDI (MOC, May 2009)<br />

Foreign Exchange<br />

Administration of<br />

Overseas Investment<br />

(SAFE, March 1989)<br />

Supplemental Provisions<br />

on Administration<br />

Measures on Foreign<br />

Exchange for Overseas<br />

Investment (SAFE,<br />

September 1995)<br />

Canceling the Deposits<br />

that Guarantee Profits<br />

from Investments<br />

Abroad (SAFE,<br />

November 2002)<br />

Simplifying<br />

Foreign Exchange<br />

Administration Relating<br />

to OFDI (SAFE, March<br />

2003)<br />

Further Measures on<br />

Foreign Exchange<br />

Administration<br />

Stimulating OFDI (SAFE<br />

May 2005)<br />

Administration<br />

Measures on Foreign<br />

Exchange for Overseas<br />

Investment (SAFE, 2009)<br />

PROOF<br />

Projects exceeding US$100 million<br />

to be approved by MOC<br />

1. SAFE evaluates the source of<br />

funds to be invested abroad as<br />

well as the foreign exchange risk<br />

2. Five percent of the OFDI sum<br />

has to be deposited in a special<br />

account<br />

3. Profit earned abroad should be<br />

remitted back to China<br />

Chinese investors are allowed to<br />

purchase foreign exchange for an<br />

OFDI project; prior to this, a<br />

Chinese investor had to earn the<br />

foreign exchange<br />

Deposits that guarantee profits are<br />

no longer needed<br />

1. SAFE will only investigate<br />

domestic foreign exchange<br />

sources<br />

2. Foreign exchange obtained from<br />

a source outside of mainland<br />

China no longer examined<br />

1. Local SAFE named as authority<br />

on OFDI projects with a higher<br />

threshold (from US$3 to US$10<br />

millions) all over the country<br />

2. Total foreign exchange available<br />

for all investors is increased from<br />

USD3.3 to USD5 billion<br />

The necessary foreign exchange for<br />

the domestic investors to invest<br />

abroad may be self-owned foreign<br />

exchange, the foreign exchange<br />

purchased by RMB or entity,<br />

intangible assets, the domestic and<br />

overseas foreign exchange loans,<br />

and other permitted source

Inspection<br />

and<br />

evaluation<br />

Guidance<br />

and support<br />

International<br />

investment<br />

protection<br />

mechanism<br />

Interim Measures for the<br />

Joint Annual Inspection<br />

of Overseas Investments<br />

(MFTEC, October 2002)<br />

Measures for<br />

Comprehensive<br />

Assessment of<br />

OFDI Performance<br />

MFTEC (October 2002)<br />

Annual Report System on<br />

Operational Obstacles in<br />

Major Target Countries<br />

(MOC, November 2004)<br />

Providing Credit Support<br />

to Key OFDI Projects<br />

Encouraged by the State<br />

(SNRC, May 2003)<br />

Guiding Directories<br />

of Target Nations<br />

and Industries for<br />

OFDI (MOC, July 2004;<br />

MOC, October 2005;<br />

MOC, January 2007)<br />

Using and Managing<br />

Special Funds for Foreign<br />

Economic Cooperation<br />

(MOC; MOF, December<br />

2005)<br />

Bilateral Investment<br />

Treaty<br />

PROOF<br />

19<br />

Provides post-investment evaluation<br />

of OFDI projects<br />

Clarification of standards and<br />

procedures for evaluating<br />

OFDI projects which have been<br />

operating overseas<br />

Using annual reports from<br />

enterprises investing abroad, MOC<br />

collects all kinds of obstacles<br />

and problems confronted by<br />

OFDI companies<br />

OFDI projects fulfilling specified<br />

requirements will be provided with a<br />

lower lending rate credit fund<br />

Provides industries and countries<br />

information for enterprises to<br />

conduct investment encouraged by<br />

the state through preferential<br />

treatment concerning funding, tax<br />

collection, foreign exchange,<br />

customs and others<br />

1. Sets up special funds to<br />

encourage Chinese enterprises to<br />

invest abroad<br />

2. Special funds may be used to<br />

support foreign economic<br />

cooperation by the following<br />

means: (1) subsidies for<br />

pre-operational fees; (2) interest<br />

discounts for medium- and<br />

long-term loans; (3) subsidies for<br />

operational fees<br />

1. In 1980s, China signed BITs with<br />

most developed countries, but in<br />

this period, most treaties are<br />

raised by developed countries to<br />

protect their investment in<br />

China<br />

2. In 1990s, China began to<br />

conclude BIT positively with<br />

developing countries to protect<br />

investment in these countries

20<br />

Table 1.1 (Continued)<br />

Key policy Key point<br />

Multilateral investment<br />

protection measures<br />

Regional protection<br />

mechanism<br />

Sources: www.mofgov.com; He (2009); Luo et al. (2010).<br />

1985<br />

Approval procedures for setting<br />

up overseas subsidiaries<br />

1985<br />

1991<br />

Administration and approval<br />

of establishing non-trade<br />

enterprises overseas<br />

1984<br />

Approval and administration<br />

of non-trading overseas enterprises<br />

1991<br />

Approval authorities and Examination and approval<br />

administrative principles for opening up of OFDI project proposals<br />

non-trade joint venture overseas and feasibility reports<br />

Acceding to WTO in 2001, China could<br />

enjoy the multilateral investment<br />

protection provided by agreements<br />

abided by WTO members, such<br />

as, Agreement on Trade-Related<br />

Investment Measures (TRIMS), General<br />

Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)<br />

China-ASEAN Free Trade Area, founded<br />

in 2002, providing adequate protection<br />

to investment in this area, benefits<br />

more and more investors both from<br />

China and ASEAN<br />

2004<br />

Examination and approval of investment to<br />

run enterprises overseas<br />

2004<br />

Verification and approval<br />

procedures for OFDI<br />

2003<br />

Reply on decentralization authority<br />

reforming pilot of non-trade<br />

investment overseas approval<br />

2009<br />

Administration of OFDI<br />

Initial regulations on OFDI<br />

Normalization of the approval and Further procedure simplification<br />

Strict examination of projects 1990 administration system<br />

and decentralization of authority<br />

1979 2000<br />

2009<br />

Highly centrally controlled authority<br />

Decentralization of authority Relaxed examination of projects<br />

Figure 1.1a Evolution of state’s examination and approval processes for China’s OFDI<br />

1990<br />

Rules for implementation of measures on<br />

foreign exchange control in investment abroad<br />

2002<br />

Canceling the deposits that guarantee<br />

profits from investments abroad<br />

1989<br />

1993<br />

Procedural and approval standards on<br />

OFDI-related foreign exchange<br />

Opening special account of<br />

risks and capital resources<br />

deposits that guarantee profits<br />

1995<br />

1989<br />

Foreign exchange administration<br />

of overseas investment<br />

Supplemental provisions on<br />

administration measures<br />

on foreign exchange<br />

for overseas investment<br />

2005<br />

Enlarging the reform pilots regarding<br />

the administration of foreign<br />

exchange for overseas investment<br />

Rules for implementation of<br />

measures on foreign exchange<br />

control in investment abroad 2009<br />

Administration measures on<br />

foreign exchange for<br />

2003<br />

overseas investment<br />

Simplifying foreign exchange<br />

administration relating to OFDI<br />

Rigid control on capital resource and<br />

More standard control on foreign Streamlining the examination on<br />

1979<br />

foreign exchange risk<br />

Profit deposits are required<br />

exchange risk, source of investment<br />

1990<br />

2000<br />

fund Chinese investors are allowed to<br />

risk and capital resource,<br />

canceling deposits and<br />

2009<br />

purchase foreign exchange<br />

decentralization authority.<br />

Figure 1.1b Evolution of state’s foreign exchange control for China’s OFDI<br />

2003<br />

PROOF

Bing Ren et al. 21<br />

2004<br />

2005<br />

Guiding directories of target<br />

Notice on adjusting the management<br />

2000 nations and industries for OFDI<br />

mode of overseas financial guarantees<br />

for overseas investment enterprises<br />

2005<br />

Measures of capital support for<br />

2004<br />

small and medium enterprises to<br />

Providing more financing support<br />

develop international markets<br />

Notice on setting up a risk to key overseas-invested projects<br />

1999<br />

prevention mechanism for key<br />

overseas investment projects<br />

Guidance on granting credit<br />

2003<br />

2005<br />

for overseas processing Providing credit support to key OFDI<br />

Using and managing special funds<br />

and assembling<br />

projects encouraged by the state<br />

for foreign economic cooperation<br />

1979 2000<br />

Support on capital, credit, and finance, guidance on target<br />

nations and industries are provided to encourage OFDI<br />

2009<br />

Figure 1.1c Evolution of state’s inspection and evaluation processes for China’s OFDI<br />

2002<br />

2003<br />

Circular on setting up an information<br />

Measures for comprehensive bank of overseas investment 2004<br />

assessment of OFDI performance intention of enterprises Annual report system on<br />

operational obstacles<br />

2002<br />

Interim measures for the joint annual<br />

inspection of overseas investments<br />

2002<br />

Provisions on statistical<br />

report of OFDI<br />

in major target countries 2005<br />

Report requirements for overseas<br />

mergers and acquisitions<br />

Annual inspection, comprehensive assessment, and other report systems are set up<br />

1979 2000 2009<br />

Figure 1.1d Guidance and support on China’s OFDI by state<br />

PROOF<br />

1985<br />

2000<br />

First BIT with developing countries<br />

Signed BIT with 54<br />

1996<br />

1982 Thailand<br />

developing countries by 2000<br />

Signed BIT with most<br />

2004<br />

First BIT with developed countries developed countries by 1996<br />

2001 China-ASEAN<br />

Sweden<br />

WTO free-trade area<br />

1979<br />

As investment host country, most BITs As investment output country, most BITs<br />

were concluded with developed countries were concluded with developing countries<br />

Seeking multilateral and<br />

regional protection 2009<br />

1990<br />

2000<br />

Figure 1.1e Evolution of China’s international investment protection mechanism<br />

Foreign Capital and Overseas Investment drafts the catalogs of guidance for<br />

foreign investment industries, and approves key OFDI projects. The Ministry<br />

of Commerce, formerly the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation<br />

and Ministry of Domestic Commerce, is the primary government<br />

unit responsible for conducting multilateral negotiations on investment and<br />

trade treaties. Finally, the Department of Outward Investment and Economic<br />

Cooperation drafts concrete regulations on OFDI and administrates and<br />

supervises OFDI.<br />

Other important governmental departments in the second layer include<br />

the People’s Bank of China, which is responsible for making monetary policy<br />

and foreign exchange policy; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responsible for

22 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

drafting the catalog for guiding the target countries of OFDI in cooperation<br />

with other agencies; and the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Taxation,<br />

responsible for drafting policies of taxation related to OFDI. The Ministry of<br />

Taxation is also responsible for providing financial support to OFDI through<br />

special funds. A special organization, the State-owned Assets Supervision<br />

and Administration Commission, was established under the State Council to<br />

manage and supervise the national state-owned assets in the non-financial<br />

sectors, including those that invest in overseas markets.<br />

In the third layer are several departments and units that implement the<br />

policies made by the above authorities. For example, the State Administration<br />

of Foreign Exchange helps supervise and check the authenticity<br />

and legality of the receipts and payments involved in OFDI and regulates<br />

management of overseas foreign exchange accounts. Three policy-oriented<br />

financial institutions help to provide credit and insurance for OFDI firms:<br />

these include the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of<br />

China, and the China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation. Figure<br />

1.2 and Table 1.2 illustrate the Chinese OFDI bureaucratic administration<br />

system.<br />

The government ownership<br />

The third formal OFDI institutional regime relates to the wide presence of<br />

government ownership of firms in the economy. Since market reform in the<br />

late 1970s, the Chinese government has maintained control of the economy.<br />

The central and local government bureaux provide funding to the SOE<br />

Ad hoc<br />

organizations<br />

SASAC<br />

SOE<br />

State council<br />

SDRC MOC PBC MOF MFA<br />

DFCOI DOIEC SAFE<br />

MOT<br />

CECIE<br />

PROOF<br />

Policy financial<br />

institution<br />

EIBC CDB<br />

Figure 1.2 Bureaucratic system in regulating China’s OFDI<br />

Notes: MOC – Ministry of Commerce; DOIEC – Department of Outward Investment and Economic<br />

Cooperation; SDRC – State Development and Reform Commission; DFCOI – Department<br />

of Foreign Capital and Overseas Investment; MFA – Ministry of Foreign Affairs; MOF – Ministry<br />

of Finance; PBC – People’s Bank of China; SASAC – State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration<br />

Commission; MOT – the Ministry of Taxation; SAFE – State Administration of Foreign<br />

Exchange; SOE – State-Owned Enterprise; EIBC – Export-Import Bank of China; CDB – China<br />

Development Bank; CECIE – China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation.<br />

Sources: www.gov.cn; www.mofcom.gov.cn; zcq.mofcom.gov.cn; www.sdpc.gov.cn (2010).

Table 1.2 The bureaucratic administration regime of China’s OFDI<br />

Department Main functions<br />

Bing Ren et al. 23<br />

State council 1. Blueprinting China’s overall OFDI in the long term<br />

MOC 1. Bilateral and multilateral negotiations on investment and<br />

trade treaties<br />

DOIEC 1. Drafting concrete regulations on OFDI<br />

2. Administrating and supervising OFDI activities<br />

3. Examining and verifying non-financial enterprises’ OFDI<br />

4. Statistics for OFDI<br />

SDRC 1. Studying and putting forward strategies and plans for OFDI<br />

2. Studying policies concerning aggregate balance and<br />

structural optimization<br />

DFCOI 1. Drafting the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign<br />

Investment Industries in cooperation with relevant agencies<br />

2. Examining and approving key OFDI projects, major<br />

resources related and consuming substantial amount of<br />

foreign currency<br />

SAFE 1. Supervising and checking the authenticity and legality of<br />

receipts and payments<br />

2. Regulating management of overseas foreign exchange<br />

accounts<br />

SASAC 1. Managing and supervising the nation’s state-owned assets in<br />

non-financial sectors<br />

MFA 1. Drafting the Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign<br />

Investment Countries in cooperation with relevant agencies<br />

MOF 1. Providing financial support to OFDI though special fund, etc<br />

2. Drafting policies of taxation related to OFDI in cooperation<br />

with MOT<br />

MOT 1. Drafting policies of taxation related to OFDI in cooperation<br />

with MOF<br />

PBC 1. Designing the monetary and foreign exchange policy, etc<br />

EIBC; CDB 1. Providing credit for OFDI firms as policy banks<br />

CECIE 1. Providing insurance for OFDI firms as policy insurance<br />

corporation<br />

Source: www.gov.cn<br />

PROOF<br />

sector; the state also directs funds to SOEs via state-owned banks. As the<br />

market economy develops further, SOEs seek financing from domestic and<br />

international financial markets. Through listing their stocks on the stock<br />

exchange markets, SOEs are transformed into corporations and joint stock<br />

companies. In a joint stock company, government ownership comprises<br />

one type of shares and, as the dominant shareholder, the state exerts tight<br />

control over both political and economic objectives. For example, SOEs are

24 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

Foreign investment enterprise<br />

Joint stock company<br />

0.5%<br />

5.6%<br />

Enterprise funded from<br />

Joint equity cooperative<br />

enterprise<br />

1.0%<br />

Limited liability company<br />

22.0%<br />

Others<br />

0.3%<br />

Private enterprise<br />

1.0%<br />

PROOF<br />

Hongkong, Macao, Taiwan<br />

0.1%<br />

Collectively owned enterprise<br />

0.3%<br />

State owned enterprise<br />

69.2%<br />

Figure 1.3 Chinese OFDI stocks’ distribution by different types of investors (2009)<br />

the main players in OFDI, relative to other types of enterprises, and behave<br />

aggressively in their internationalization. Figure 1.3 describes the presence<br />

of SOEs within Chinese OFDI. Table 1.3 lists the top 50 SOEs ranked by<br />

FDI outflow.<br />

SOEs, in their drive toward globalization, have encountered strong criticism<br />

from global stakeholders for their lack of accountability, transparency,<br />

and trustworthiness (Pistor and Xu, 2005; Luo & Tung, 2007; Li, 2009).<br />

When Chinese SOEs invest overseas, their strategies may be purely economic,<br />

such as maximizing profits, or they may include political goals<br />

that take priority over economic ones. In fact, the influence of the state<br />

and adoption of the administrative governance framework in SOE business<br />

activities make economic efficiency largely unclear. The literature<br />

argues that the highly concentrated ownership gives the state substantial<br />

discretionary power to use the resources of companies and results in problems<br />

such as insider control and the exploitation of minority shareholder<br />

interests (Young, Peng, Ahlstrom, Bruton, & Jiang, 2008). Control by the<br />

government may also create a fertile soil to nurture corruption (Luo &<br />

Tung, 2007). A recent study suggests that the newly transformed SOEs are<br />

‘dynamic dynamos’ rather than ‘dying dinosaurs’ (Ralston, Tong, Terpstra,<br />

Wang, & Egri, 2006), suggesting that government ownership may influence<br />

the performance of Chinese firms positively, including OFDI.<br />

2.3. Informal institutional regime<br />

The state also plays a role in cultivating, advocating, and strengthening<br />

informal institutions to enhance its economic and political objectives<br />

through OFDI. Except for the formal institutional frameworks discussed<br />

above, informal institutions – especially when non-existent or non-enforced<br />

legal systems fail to support business – influence firms’ overseas investments.

Table 1.3 Top 50 non-financial Chinese enterprises ranked by OFDI stocks (2009)<br />

No. Enterprise name Main business Firm type<br />

1 China National<br />

Petroleum Corporation<br />

2 China National<br />

Offshore Oil<br />

Corporation<br />

3 China Petrochemical<br />

Corporation<br />

4 Aluminium<br />

Corporation of China<br />

5 China Resources<br />

(Holdings) Co., Ltd.<br />

6 China Ocean Shipping<br />

(Group) Company<br />

7 China National<br />

Cereals, Oils &<br />

Foodstuffs Corporation<br />

Crude oil and gas<br />

exploitation, petroleum<br />

refining, engineering<br />

Crude oil and gas<br />

exploitation, petroleum<br />

refining, engineering<br />

Crude oil and gas<br />

exploitation, petroleum<br />

refining, engineering<br />

Bauxite, rare-earth metal,<br />

engineering<br />

Consumer goods, power,<br />

property, cement, gas,<br />

medication, finance<br />

Water transportation,<br />

shipbuilding, logistics<br />

Foodstuffs, grain and oil,<br />

hotel, real estate<br />

8 Sinohem Corporation Oil, fertilizer, gas, hotel, real<br />

estate<br />

9 China Merchants<br />

Group<br />

10 China National<br />

Aviation Holding<br />

Corporation<br />

11 China Shipping<br />

(Group) Company<br />

Transportation,<br />

infrastructure, finance, real<br />

estate<br />

25<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Air transportation Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Water transportation,<br />

shipbuilding, logistics<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

12 SinoSteel Corporation Metallurgy, engineering Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

13 SINOTRANS<br />

Changjiang National<br />

Shipping (Group)<br />

Corporation<br />

14 China Minmetals<br />

Corporation<br />

Transportation, recreation,<br />

real estate<br />

Metal and mineral,<br />

transportation<br />

15 CITIC Group Finance, real estate,<br />

engineering, resource,<br />

manufacture, information,<br />

commercial service<br />

PROOF<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Limited liability<br />

company

26<br />

Table 1.3 (Continued)<br />

No. Enterprise name Main business Firm type<br />

16 China Unicom<br />

Corporation<br />

17 China State Construction<br />

Engineering Corporation<br />

18 China Power Investment<br />

Corporation<br />

Telecommunications Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Civil construction Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Electric power,<br />

investment, engineering<br />

19 China Huaneng Group Electric power, finance,<br />

resource, finance<br />

20 China National Chemical<br />

Corporation<br />

21 China Mobile<br />

Communications<br />

Corporation<br />

22 China Metallurgical<br />

Group Corporation<br />

23 Shum Yip Holdings<br />

Company Limited<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Chemical engineering Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Telecommunications Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Metallurgy, resource, real<br />

estate, engineering<br />

Real estate, infrastructure,<br />

transportation<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Locally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

24 Legend Holdings Ltd. IT, investment, real estate Limited liability<br />

company<br />

25 Hunan Valin Iron & Steel<br />

(Group) Co., Ltd.<br />

Iron and steel Limited liability<br />

company<br />

26 GDH Limited Investment Locally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

27 Huawei Technologies Telecommunication<br />

service<br />

28 China Noferrous Metal<br />

Mining & Construction<br />

(Group) Co., Ltd.<br />

29 China Norh Industries<br />

Group Corporation<br />

30 Baosteel Group<br />

Corporation<br />

31 Shanghai Baosteel Group<br />

Corporation<br />

32 Shanghai Overseas United<br />

Investment Co., Ltd.<br />

33 Guangzhou Yuexiu<br />

Holdings Limited<br />

34 Anshan Iron & Steel<br />

Group Corporation<br />

35 State Grid Corporation of<br />

China<br />

Non-ferrous metal,<br />

engineering<br />

Limited liability<br />

company<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Military supplies Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Steel, resource, finance,<br />

manufacture, service<br />

Steel<br />

PROOF<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Investment Limited liability<br />

company<br />

Investment Limited liability<br />

company<br />

Iron, steel Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Power grid Centrally controlled<br />

SOE

36 Shanghai Automotive<br />

Industry Corporation<br />

Bing Ren et al. 27<br />

Auto manufacture Limited liability<br />

company<br />

37 Shougang Corporation Steel, resource, service Limited liability<br />

company<br />

38 Sinohydro Co., Ltd. Water conservancy,<br />

investment, engineering,<br />

service, trade<br />

39 Nam Kwong (Group)<br />

Company Limited<br />

40 Shenzhen Investment<br />

Holdings Co., Ltd.<br />

41 Shenhua Group<br />

Corporation<br />

42 China Poly Group<br />

Corporation<br />

Consumer goods, real<br />

estate, hotel, logistics<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Investment Limited liability<br />

company<br />

Resource Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

International trade, real<br />

estate, culture, resource<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

43 TCL Group Company Electronic products Limited liability<br />

company<br />

44 Aviation Industry<br />

Corporation of China<br />

Aerospace manufacture,<br />

military<br />

Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

45 Jinchuan Group Limited Resource Locally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

46 Xinjiang Zhongxin<br />

Resource Co., Ltd.<br />

47 Guangdong National<br />

Shipping Corporation<br />

48 Wuhan Iron & Steel<br />

(Group) Co., Ltd.<br />

Resource Locally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Transportation, logistics,<br />

real estate, recreation<br />

49 ZTE Corporation Telecommunication<br />

service<br />

50 China Guangdong<br />

Nuclear Power Holding<br />

Co., Ltd.<br />

Locally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Metallurgy, engineering Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Limited liability<br />

company<br />

Nuclear resource Centrally controlled<br />

SOE<br />

Sources: 2009 Statistical Bulletin of China’s OFDI (MOC, 2010); www.sasac.gov.cn.<br />

PROOF<br />

The state helps to create two important informal institutions that generate<br />

ideological influence on Chinese OFDI: state ideology and national pride.<br />

State ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes state goals, expectations,<br />

and actions, and it can be thought of as a comprehensive vision of the<br />

state held by all members of society. According to Smith and Kim (2006),<br />

national pride is ‘the positive effect that the public feels towards their country,<br />

resulting from their national identity (P127)’. These two factors are<br />

to some extent interrelated. A strong state ideology may increase national

28 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

PROOF<br />

pride, and national pride can also enhance state ideology. While the economic<br />

organization is intertwined with the ideological state, major Chinese<br />

multinationals usually incorporate national missions and national pride in<br />

conducting overseas strategies. Such ideology and pride may stem from the<br />

collective expectation of ‘carrying a great torch and striving to better develop<br />

the country’. Sometimes, a particular strategy at the firm level (such as a<br />

cross-border acquisition) is economically irrational (Hope et al., 2010). This<br />

could stem from an individual enterprise leaders’ greater ambition to pursue<br />

a successful ‘country image’ to foreign counterparts and infiltrate the<br />

‘Chinese brand’ into a global market.<br />

We argue that state ideology and national pride are two soft power institutions<br />

that may function as growth engines for Chinese firms to compete<br />

with international players. The effect of state ideology and national pride are<br />

more likely to be cultivated in the Chinese context because the Chinese culture<br />

is strong in collectivism and nationalism in comparison with the West.<br />

Such national culture allows the state to communicate ideology and pride<br />

through tangible and intangible social and cultural platforms as well as to<br />

create incentives and enforcement mechanisms. To fulfill its country-level<br />

strategies and thus have greater influence on the international investments<br />

of Chinese firms, the government stresses such state ideologies throughout<br />

its policy and administration process, as well as directly implements them<br />

in its wholly controlled SOEs. Hence, the formal OFDI institutional regimes<br />

further ensure the efficiency of the informal institutional-enforced effects on<br />

OFDI in China.<br />

2.4. Institutional and Chinese MNE-based OFDI<br />

We argue that the state plays important roles in shaping Chinese OFDI<br />

institutional regimes, including the formal and informal institutions. It is<br />

important to explore more thoroughly what theoretical implications we can<br />

draw from this phenomenon. Dunning and Lundan (2008) suggest that<br />

institutions influence multinational ownership, internalization, and location<br />

advantages, and thus determine the internationalization strategy of a<br />

company. Integrating institutions into the OLI paradigm offers a profound<br />

tool to understand how institutions help the formation of emerging multinational<br />

firms. Sun and colleagues (2010) propose a comparative ownership<br />

advantage framework to explain why EMEs such as those from China and<br />

India can internationalize and conduct specific cross-border M&As. The theory<br />

suggests that EMEs in developing countries can leverage country-specific<br />

advantages and combine them with firm-specific advantages to form comparative<br />

ownership advantages to drive their internationalization.<br />

Combining the ideas of Dunning and colleagues (Dunning, 2001;<br />

Dunning & Lundan, 2008) with those of Sun and colleagues (Sun et al.,<br />

2010), we argue that not only the factor endowment structure but also the

PROOF<br />

Bing Ren et al. 29<br />

institutional structure help EMEs generate comparative ownership advantages.<br />

Hence, we can broaden the country-specific advantages concept to<br />

include an institutional dimension, suggesting that institutions could be<br />

leveraged by EMEs to combine with company advantages to form specific<br />

ownership advantages. These institutional factors could be the formal and<br />

informal ones shaped under the role of state. For example, formal institutions<br />

(such as favorable credit and financing policies and the establishment<br />

of resource and information platforms overseas) can be combined with company<br />

production and entrepreneurial capabilities to exploit international<br />

market opportunities. From the informal institutional perspective, managing<br />

the state ideology and national pride institutional elements in the<br />

strategic management processes of companies can help them better co-opt<br />

the formal institutional regimes, thus maximizing globalization benefits.<br />

In essence, through a successful integration of the national level institutional<br />

advantages and the company level advantage, EMEs can build<br />

‘institution-based comparative ownership advantages’. With this institutionbased<br />

comparative ownership advantage, EMEs can cultivate business opportunities<br />

in specific host country markets and conduct institution-based<br />

OFDI.<br />

Proposition 1: The formal and informal institutions developed under the role<br />

of the state are sources of comparative ownership advantage for Chinese firms, to<br />

‘pull’ Chinese firms to conduct institution-based OFDI.<br />

2.5. The strategic choices of OFDI by Chinese multinationals<br />

While institutions are helpful for developing firm-specific ownership advantage,<br />

corporate executives may view the institutional framework as a favorable<br />

pull factor for internationalization (Lewin, Long, & Carroll, 1999).<br />

On the one hand, they increase EME confidence in internationalization.<br />

On the other hand, they can be exploited to change the cost and benefit<br />

structure in a multinational’s potential OFDI activity in a host country<br />

market. We will discuss Chinese multinational strategic choices in<br />

OFDI below.<br />

Choice of OFDI mode<br />

In contrast to mature market multinationals, EMEs have fewer incentives<br />

for efficiency-seeking and cost-minimizing outward investments, as the EME<br />

itself has ample supplies of low-cost, productive labor and inexpensive land.<br />

Rather, Chinese firms have higher incentives for asset-seeking and marketseeking<br />

OFDI. In comparison to independent OFDI and contractual joint<br />

ventures, M&A strategy can help Chinese firms to more quickly access<br />

strategic assets and potential markets, and thus upgrade their global competence<br />

more efficiently. However, in these aggressive cross-border M&As,<br />

the pressures of managing strategic and operating risks are much higher

30 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

PROOF<br />

than when seeking only cost efficiency (Kumar, 2009). We believe the formal<br />

and informal institutions mentioned above will help overcome the risks<br />

and facilitate adopting the M&A mode.<br />

Formal institutional support will help the resource and domestic market<br />

demand of potential multinationals and thus facilitate more entrepreneurial<br />

and aggressive international exploration. Formal institutional support also<br />

allows firms to focus on managing the strategic and operating risks in<br />

M&As with greater efficiency. The informal institutions can help intrinsically<br />

reinforce political or strategic objectives of the involving parties. These<br />

arguments suggest that formal and informal institutional supports can help<br />

Chinese multinationals adopt more aggressive OFDIs such as M&As.<br />

Proposition 2: In relation to independent OFDI and greenfield joint ventures,<br />

Chinese multinationals are more likely to adopt acquisition in their internationalization.<br />

Choice of OFDI location<br />

Multinationals invest in the most advantageous locations to fulfill the firm’s<br />

efficiency, asset- and market-seeking strategic objectives (Dunning, 1980,<br />

1988). In Chinese OFDI, the endogenous formal and informal institutions,<br />

shaped by the role of the state, help determine location choice. Regarding<br />

formal institutions, the government encourages firms to target resource<br />

and strategic asset-intensive regions through various preferential policy supports<br />

such as credit and tax incentives, as well as other administrative<br />

methods. For example, Chinese SOEs enter countries such as Africa and<br />

South America more extensively because they are resource-intensive countries<br />

where the Chinese state can acquire strategic raw materials to enhance<br />

the country-level resource endowments. Examples include Capital Iron &<br />

Steel’s acquisition of Hierro Peru Mining and Baosteel’s investment in a steel<br />

plant in Brazil. Informal institutions also influence which countries Chinese<br />

firms enter, including those helpful for maintaining Chinese national pride.<br />

The Chinese prefer to invest in regions where national pride and state ideology<br />

can be better maintained and leveraged. For example, regions such as<br />

Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong (the so-called ‘four dragons’),<br />

as well as Malaysia, one of the new ‘four tigers’, give better location<br />

advantages (Sun et al., 2010). These institutional enforcements will help set<br />

the boundaries of locations for Chinese OFDI.<br />

Proposition 3: Chinese multinational firms tend to invest in countries or regions<br />

where both formal and informal institutions developed under the role of the state<br />

are more likely to play a role.<br />

Choice of OFDI industry<br />

We believe formal institutions play a major role in guiding OFDI industry<br />

choice. As the Chinese government views OFDI as an important means

Bing Ren et al. 31<br />

of integrating global resources and value chain markets, its aim is carried<br />

out mainly through securing stable sources of raw materials and obtaining<br />

technological assets scarce in China. The government has specifically<br />

encouraged OFDI in the resource exploration and extraction industries (Cai,<br />

1999) as well as the manufacturing (processing and assembling) industries<br />

where Chinese companies have a competitive edge. But these Chinese<br />

industries are weak in designing, researching and developing (R&D) and,<br />

through preferential policies and direct administrative control, the government<br />

is encouraging OFDI. The government has recently favored more<br />

investments in the financial sector overseas. China Investment Corporation<br />

(CIC) invested in Blackstone and Morgan Stanley to use the global<br />

financial crisis to leverage China’s huge foreign currency reserves. However,<br />

we do not regard these overseas investments as traditional MNE behavior<br />

explained by theory. Informal institutions support formal institutions in<br />

deciding which sectors should be involved in OFDI. Some target OFDI industries<br />

may involve greater elements of national pride and state ideology to<br />

help generate greater political benefits. Because of the ideology concern, it<br />

may be hard for Chinese multinationals to conduct OFDI in industries that<br />

generate ideology conflicts such as the media sector. Figure 1.4 synthesizes<br />

the above propositions in this <strong>chapter</strong>.<br />

Proposition 4a: Chinese multinational firms tend to invest in overseas manufacturing<br />

(design and R&D) industries that can help upgrade their domestic industrial<br />

structure and global value chains.<br />

Proposition 4b: Chinese multinational firms tend to invest in overseas resource<br />

exploration and extraction industries that can help China pursue and secure scarce<br />

natural resources.<br />

Hard power (economic)<br />

Formal institutional<br />

determinants<br />

State policy<br />

Administrative<br />

system<br />

Government<br />

ownership<br />

The state Soft power (political)<br />

Chinese multinationals’<br />

comparative ownership<br />

advantages<br />

Chinese multinationals’<br />

OFDI:<br />

motivation<br />

strategy<br />

PROOF<br />

Informal institutional<br />

determinants<br />

State ideology<br />

National pride<br />

Figure 1.4 The role of state and Chinese multinationals’ institution-based OFDI

32 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

3. Discussion and conclusion<br />

PROOF<br />

As China emerges as an important player in the world economy, the<br />

role of the state is crucial through the promotion of OFDI by Chinese<br />

multinationals. The Chinese state executed its role through constructing<br />

formal and informal institutions to influence OFDI trajectories. Under such<br />

circumstances, we observe an extensive interplay between the macro-level<br />

state policy and institutional frameworks and the micro-level firm and OFDI<br />

strategic choices. In both cases, formal and informal institutional factors<br />

drive Chinese firms to conduct OFDI in different investment modes, location<br />

choices, and types of industries.<br />

Due to space limitation, there are some important issues our <strong>chapter</strong> did<br />

not capture in detail although they deserve attention. Institutions do not<br />

matter to all firms, and they do not matter in similar ways (North, 1990;<br />

Scott, 1995). This suggests that the institutions derived from the role of the<br />

state may generate contingent effects on OFDI by Chinese firms. The first<br />

contingent factor is related to a stratified structure that the state constructs<br />

in developing the formal and informal institutional OFDI regime. In such<br />

a structure, the institutional regime is exclusive in nature where the state<br />

renders the advantageous institutions only to certain groups of firms: not all<br />

Chinese multinationals enjoy the benefits in their internationalization. The<br />

state makes such exclusions using criteria such as how important the firm is<br />

to the whole economy. Only influential firms such as large firms or firms in<br />

more important industries benefit from the supportive regime.<br />

The second contingency factor is related to a ‘double-edged sword’ or ‘dark<br />

side’ of the institutional influence. In contrast to the ‘benefits’ generated<br />

by institutional regimes for ‘some’ firms, there may be ‘costs’ or ‘liabilities’<br />

assigned by similar institutions to other firms. While we discuss the pull role<br />

of the state and institutional regimes on Chinese OFDI, we cannot ignore the<br />

push role of the same institutional regime to some OFDI activities (e.g., Luo<br />

& Tung, 2007; Witt & Lewin, 2007). The ‘supporting’ institutional regime<br />

may create costs and disadvantages to some firms’ domestic market competition,<br />

and thus crowd them out to the international markets to pursue<br />

growth. This is reflected by the large number of Chinese overseas investments<br />

in Latin America, many of them in three tax havens (Witt & Lewin,<br />

2007).<br />

The third contingency factor is related to the ‘mixed’ objectives that the<br />

state sets for OFDI (Luo and Tung, 2007; Luo et al., 2010). Except for the<br />

economic driving forces (mostly efficiency and effectiveness from the firm’s<br />

perspective), Chinese firms are also pulled to conduct political OFDI that<br />

mostly satisfies country-level objectives. Key Chinese multinationals are<br />

forced to exert ‘helping hand’ behaviors to fulfill the country-level political<br />

goals such as strengthening inter-governmental political ties (Luo and Tung,<br />

2007). This was particularly evident in China’s investment in some Third

Bing Ren et al. 33<br />

World countries (Luo and Tung, 2007). The state is more likely to mandate<br />

SOEs to conduct such OFDI activities because the state has a direct control<br />

of the SOE sector. Such political mandates may also be possible with private<br />

firms, especially when the private parties’ interests are intertwined with<br />

the state’s interests. However, compared with SOEs, private sector firms are<br />

more likely to act independently in OFDI and be driven by economics, even<br />

when such OFDIs result from exploiting the state’s supportive institutional<br />

regime.<br />

The last contingency is that to leverage better the advantageous OFDI<br />

institutional regime, firms must have specific internal conditions. The most<br />

important internal conditions are capabilities that can facilitate successful<br />

integration of company resources and OFDI objectives with the countryspecific<br />

institutional supports. Such capabilities include strong adaptation<br />

capabilities in relation to the external institutional environments (Elango &<br />

Pattnaik, 2007; Yiu et al., 2007); cross-border learning and absorptive capacity<br />

(Johanson & Vahlne, 1997; Teece et al., 1997); and creativity and innovation<br />

in company integration of global value chains (Sun et al., 2010). Other<br />

factors can be managerial intentionality (Hutzschenreuter, Pedersen, &<br />

Volberda, 2007; Kumar, 2009) and international entrepreneurship (Yiu et al.,<br />

2007). Given the supporting institutional environments, these factors are<br />

important for generating effective strategic choices and adjustments in<br />

exploiting international market opportunities. The capability factor is more<br />

important than resources (Deng, 2007; Sun et al., 2010) because firms with<br />

unique capabilities can obtain essential resources that they lack, either<br />

through exploiting the home country institutional environments or through<br />

integrating the global resource platform.<br />

These four contingency views suggest future research directions on<br />

Chinese firms’ internationalization, to derive better predictions on the path<br />

and trajectory of Chinese OFDI: these need to include other theoretical<br />

approaches such as political economy perspectives; views on resource and<br />

capability; evolutionary theory; and the institutional perspective.<br />

References<br />

PROOF<br />

Aliber, R.Z. 1971. The multinational enterprise in a multicurrency world. In<br />

J.H. Dunning (ed.), The Multination Enterprise. London: Allen and Unwin.<br />

Boisot, M. & Meyer, M. 2008. Which way through the open door? Reflections on the<br />

internationalization of Chinese firms. Management and Organization Review, 4(3):<br />

349–365.<br />

Buckley, P.J. & Casson, M. 1976. The Future of the Multinational Enterprise. London:<br />

<strong>Palgrave</strong> Macmillan.<br />

Buckley, P.J., Clegg, L.J., Cross, A.R., Lin, X., Voss, H. & Zheng, P. 2007. The<br />

determinants of Chinese outward FDI. Journal of International Business Studies, 38:<br />

499–518.

34 Macro-Environmental Determinants of Chinese FDI<br />

PROOF<br />

Buckley, P.J., Cross, A.R., Tan, H., Liu, X. & Voss, H. 2008. Historic and emergent<br />

trends in Chinese outward direct investment. Management International Review,<br />

48(6): 715–748.<br />

Cai, K.G. 1999. Outward foreign direct investment: A novel dimension of China’s<br />

integration into the regional and global economy. China Quarterly, 60(4): 856–880.<br />

Caves, R.E. 1971. Industrial corporations: The industrial economics of foreign investment.<br />

Econometrica, 38: 1–27.<br />

Chang, H.-J. 1994. The Political Economy of Industrial Policy. London and Basingstoke:<br />

<strong>Palgrave</strong> Macmillan.<br />

Child, J. & Rodrigues, S.B. 2005. The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for<br />

theoretical extension? Management and Organization Review, 1(3): 381–410.<br />

Claessens, S., Djankov, S. & Lang, L. 2000. The separation of ownership and control<br />

in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58: 81–112.<br />

Deng, P. 2004. Outward investment by Chinese MNCs: Motivations and implications.<br />

Business Horizon, 47(3): 8–16.<br />

Deng, P. 2009. Why do Chinese firms tend to acquire strategic assets in international<br />

expansion? Journal of World Business, 44(1): 74–84.<br />

Dierickx, I. & Cool, K. 1989. Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive<br />

advantage. Management Science, 35(12): 1504–1511.<br />

Dore, R.P. 1990. British Factory – Japanese Factory. Berkeley: University of California<br />

Press.<br />

Dunning, J.H. 1958. American Investment in British Manufacturing Industry. London:<br />

George Allen and Unwin.<br />

Dunning, J.H. 1980. Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some<br />

empirical tests. Journal of International Business Studies, 11(1): 9–31.<br />

Dunning, J.H. 1988. Explaining International Production. London: Unwin Hyman.<br />

Dunning, J.H. 1993. Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy. Wokingham:<br />

Addison-Wesley.<br />

Dunning, J.H. 2001. The eclectic (OLI) paradigm of international production: Past,<br />

present and future. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 8(2): 173–190.<br />

Dunning, J.H. & Pitelis, C. 2009. The Political Economy of Globalization – Revisiting<br />

Stephen Hymer 50 Years On. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1505450.<br />

Dunning, J.H. & Lundan, S.M. 2008. Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy,<br />