Muscle strength and qualitative jump-landing differences in male ...

Muscle strength and qualitative jump-landing differences in male ...

Muscle strength and qualitative jump-landing differences in male ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

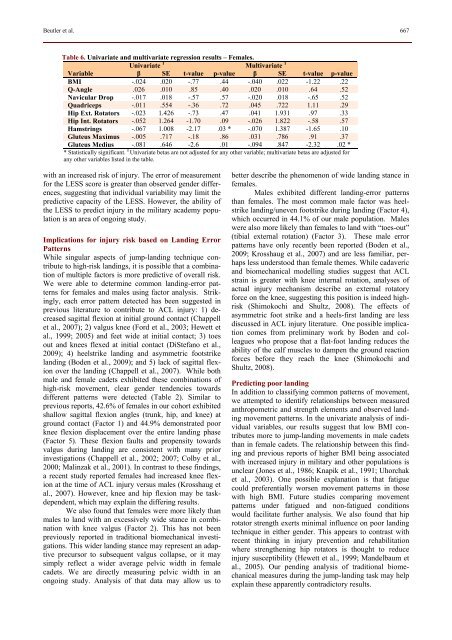

Beutler et al. 667Table 6. Univariate <strong>and</strong> multivariate regression results – Fe<strong>male</strong>s.Univariate 1 Multivariate 1Variable β SE t-value p-value β SE t-value p-valueBMI -.024 .020 -.77 .44 -.040 .022 -1.22 .22Q-Angle .026 .010 .85 .40 .020 .010 .64 .52Navicular Drop -.017 .018 -.57 .57 -.020 .018 -.65 .52Quadriceps -.011 .554 -.36 .72 .045 .722 1.11 .29Hip Ext. Rotators -.023 1.426 -.73 .47 .041 1.931 .97 .33Hip Int. Rotators -.052 1.264 -1.70 .09 -.026 1.822 -.58 .57Hamstr<strong>in</strong>gs -.067 1.008 -2.17 .03 * -.070 1.387 -1.65 .10Gluteus Maximus -.005 .717 -.18 .86 .031 .786 .91 .37Gluteus Medius -.081 .646 -2.6 .01 -.094 .847 -2.32 .02 ** Statistically significant. 1 Univariate betas are not adjusted for any other variable; multivariate betas are adjusted forany other variables listed <strong>in</strong> the table.with an <strong>in</strong>creased risk of <strong>in</strong>jury. The error of measurementfor the LESS score is greater than observed gender <strong>differences</strong>,suggest<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong>dividual variability may limit thepredictive capacity of the LESS. However, the ability ofthe LESS to predict <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong> the military academy populationis an area of ongo<strong>in</strong>g study.Implications for <strong>in</strong>jury risk based on L<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g ErrorPatternsWhile s<strong>in</strong>gular aspects of <strong>jump</strong>-l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g technique contributeto high-risk l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gs, it is possible that a comb<strong>in</strong>ationof multiple factors is more predictive of overall risk.We were able to determ<strong>in</strong>e common l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g-error patternsfor fe<strong>male</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>male</strong>s us<strong>in</strong>g factor analysis. Strik<strong>in</strong>gly,each error pattern detected has been suggested <strong>in</strong>previous literature to contribute to ACL <strong>in</strong>jury: 1) decreasedsagittal flexion at <strong>in</strong>itial ground contact (Chappellet al., 2007); 2) valgus knee (Ford et al., 2003; Hewett etal., 1999; 2005) <strong>and</strong> feet wide at <strong>in</strong>itial contact; 3) toesout <strong>and</strong> knees flexed at <strong>in</strong>itial contact (DiStefano et al.,2009); 4) heelstrike l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> asymmetric footstrikel<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g (Boden et al., 2009); <strong>and</strong> 5) lack of sagittal flexionover the l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g (Chappell et al., 2007). While both<strong>male</strong> <strong>and</strong> fe<strong>male</strong> cadets exhibited these comb<strong>in</strong>ations ofhigh-risk movement, clear gender tendencies towardsdifferent patterns were detected (Table 2). Similar toprevious reports, 42.6% of fe<strong>male</strong>s <strong>in</strong> our cohort exhibitedshallow sagittal flexion angles (trunk, hip, <strong>and</strong> knee) atground contact (Factor 1) <strong>and</strong> 44.9% demonstrated poorknee flexion displacement over the entire l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g phase(Factor 5). These flexion faults <strong>and</strong> propensity towardsvalgus dur<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g are consistent with many prior<strong>in</strong>vestigations (Chappell et al., 2002; 2007; Colby et al.,2000; Mal<strong>in</strong>zak et al., 2001). In contrast to these f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs,a recent study reported fe<strong>male</strong>s had <strong>in</strong>creased knee flexionat the time of ACL <strong>in</strong>jury versus <strong>male</strong>s (Krosshaug etal., 2007). However, knee <strong>and</strong> hip flexion may be taskdependent,which may expla<strong>in</strong> the differ<strong>in</strong>g results.We also found that fe<strong>male</strong>s were more likely than<strong>male</strong>s to l<strong>and</strong> with an excessively wide stance <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ationwith knee valgus (Factor 2). This has not beenpreviously reported <strong>in</strong> traditional biomechanical <strong>in</strong>vestigations.This wider l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g stance may represent an adaptiveprecursor to subsequent valgus collapse, or it maysimply reflect a wider average pelvic width <strong>in</strong> fe<strong>male</strong>cadets. We are directly measur<strong>in</strong>g pelvic width <strong>in</strong> anongo<strong>in</strong>g study. Analysis of that data may allow us tobetter describe the phenomenon of wide l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g stance <strong>in</strong>fe<strong>male</strong>s.Males exhibited different l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g-error patternsthan fe<strong>male</strong>s. The most common <strong>male</strong> factor was heelstrikel<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g/uneven footstrike dur<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g (Factor 4),which occurred <strong>in</strong> 44.1% of our <strong>male</strong> population. Maleswere also more likely than fe<strong>male</strong>s to l<strong>and</strong> with “toes-out”(tibial external rotation) (Factor 3). These <strong>male</strong> errorpatterns have only recently been reported (Boden et al.,2009; Krosshaug et al., 2007) <strong>and</strong> are less familiar, perhapsless understood than fe<strong>male</strong> themes. While cadaveric<strong>and</strong> biomechanical modell<strong>in</strong>g studies suggest that ACLstra<strong>in</strong> is greater with knee <strong>in</strong>ternal rotation, analyses ofactual <strong>in</strong>jury mechanism describe an external rotatoryforce on the knee, suggest<strong>in</strong>g this position is <strong>in</strong>deed highrisk(Shimokochi <strong>and</strong> Shultz, 2008). The effects ofasymmetric foot strike <strong>and</strong> a heels-first l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g are lessdiscussed <strong>in</strong> ACL <strong>in</strong>jury literature. One possible implicationcomes from prelim<strong>in</strong>ary work by Boden <strong>and</strong> colleagueswho propose that a flat-foot l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g reduces theability of the calf muscles to dampen the ground reactionforces before they reach the knee (Shimokochi <strong>and</strong>Shultz, 2008).Predict<strong>in</strong>g poor l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gIn addition to classify<strong>in</strong>g common patterns of movement,we attempted to identify relationships between measuredanthropometric <strong>and</strong> <strong>strength</strong> elements <strong>and</strong> observed l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gmovement patterns. In the univariate analysis of <strong>in</strong>dividualvariables, our results suggest that low BMI contributesmore to <strong>jump</strong>-l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g movements <strong>in</strong> <strong>male</strong> cadetsthan <strong>in</strong> fe<strong>male</strong> cadets. The relationship between this f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> previous reports of higher BMI be<strong>in</strong>g associatedwith <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>jury <strong>in</strong> military <strong>and</strong> other populations isunclear (Jones et al., 1986; Knapik et al., 1991; Uhorchaket al., 2003). One possible explanation is that fatiguecould preferentially worsen movement patterns <strong>in</strong> thosewith high BMI. Future studies compar<strong>in</strong>g movementpatterns under fatigued <strong>and</strong> non-fatigued conditionswould facilitate further analysis. We also found that hiprotator <strong>strength</strong> exerts m<strong>in</strong>imal <strong>in</strong>fluence on poor l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gtechnique <strong>in</strong> either gender. This appears to contrast withrecent th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jury prevention <strong>and</strong> rehabilitationwhere <strong>strength</strong>en<strong>in</strong>g hip rotators is thought to reduce<strong>in</strong>jury susceptibility (Hewett et al., 1999; M<strong>and</strong>elbaum etal., 2005). Our pend<strong>in</strong>g analysis of traditional biomechanicalmeasures dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>jump</strong>-l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g task may helpexpla<strong>in</strong> these apparently contradictory results.