You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

KENYA PROGRAMME<strong>2008</strong> <strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Report</strong>

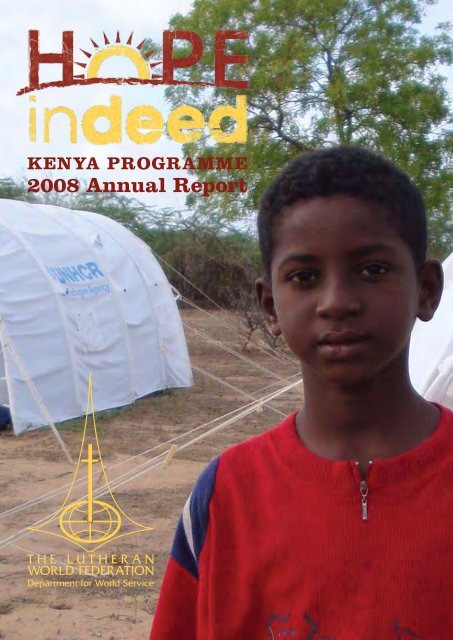

KENYA PROGRAMME<strong>2008</strong> <strong>Annual</strong> <strong>Report</strong>Our VisionA society in <strong>Kenya</strong> which reflects the care for God’s creation, and where peace, dignity, harmony,and social and economic justice prevail.Our MissionLWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> seeks to address the causes and consequences of human suffering and povertyamongst some of the most vulnerable communities in <strong>Kenya</strong>, through participatory relief anddevelopment interventions in partnership with local communities, organizations and institutions.For more information, contact:<strong>Kenya</strong> Country RepresentativeP.O. Box 40870-00100Nairobi, <strong>Kenya</strong>Philip-wijmans@lwfkenya.orgwww.lwfkenyasudan.orgUphold the rights of the poor and oppressedCover photo: A refugee who lives in oneof the camps in Dadaab, <strong>Kenya</strong>. More than200,000 refugees, mostly from Somalia, livein three camps. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> managesseveral key parts of the camps.Photo by Sofia MalmqvistProject manager, writer and editor: Stephen H. PadreAll photos by Stephen H. Padre unless otherwise noted.Design: Aaron MaurerPrinting: One To One Printers, NairobiPhoto by LWF staff

CONTENTSFeatures and reporting on main project areas2Country Representative’s Foreword3<strong>Kenya</strong> map and profile4Dadaab Refugee Assistance Project12 Turkana District Host8Community ProjectKakuma Refugee Camp16<strong>Report</strong> on special projectto respond to post-electionviolence in <strong>Kenya</strong>17Finances19StaffSome of the common acronyms used in this reportACTLWF/DWSUNHCRAction by Churches Together InternationalLutheran World Federation/Department for World ServiceUnited Nations High Commissioner for Refugees1

FOREWORDPeople are at the heart of what we do, the essence of LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>’s existence. The people wework with are seeking hope, have hope and/or even see their hope fulfilled. Under difficult and oftenforced circumstances, many people we work with creatively deal with challenges in their lives, findsolutions, and try to improve their children’s lives, themselves and their communities. This is whatwe believe our business is, and we are very good at it: Helping people build their lives with hope. Intangible actions – in deed – LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> offers hope, and hope is truly – indeed – somethingthat we can provide.LWF/DWS has been working with the people of Sudan for more than 30 years, following themwherever they went, both inside and outside Sudan, to assist them and to offer hope. Now the LWF/DWS Sudan programme, independent from the LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> programme, is forging ahead tohelp people build their livelihoods within Sudan. Many Sudanese refugees who have been under thecare of LWF/DWS in <strong>Kenya</strong> are returning to their roots, where they lived before, where they wantto live again. Many go because the full extent of services in Kakuma Refugee Camp in <strong>Kenya</strong> is nolonger offered. Refugees do not like that their children cannot attend school, and so they are seekingsolutions in Sudan or even in <strong>Kenya</strong>. That means that people are able to move about, use their lifeskills, learn about their environment, push their boundaries, and find solutions. However, there willalways be many refugees in Kakuma from various countries who do not have much hope, and we willbe with them for as long as it takes, holding on to hope for them and with them.LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> must be where there are needs, irrespective of whom and what the peopleare. We step in to help provide hope. In Somalia, the situation is so bad that one cannot even findthe right words to describe it. The lives of its citizens have been turned upside down for decades, andthe situation is only worsening. Somalis are resilient – some would even say tough, hard, rough, andviolent. But the fact is that the situation in the country is so severe that one has to be all those thingsin order to just survive. But in Dadaab, a town in <strong>Kenya</strong> where thousands of Somalis have fled to findrefuge, life is not easy either. Despite the many good humanitarian agencies that are working thereto improve conditions for the refugee residents, it is a hard place to be. The Dadaab refugee camps,where LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> has been developing its operations as a lead agency, have gained a reputationin Somalia as heaven and a safe haven. Somalis want to go to Dadaab if they have the chance toflee their country. And people came in <strong>2008</strong> more than ever before. The normal resilience of peoplehas been tested to the limit, and many are running out of strength. Some are losing hope.LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> is helping people through different stages in their lives as refugees. In thefirst stage, we are helping people with their basic needs. With other humanitarian agencies, we arealso providing safe transit to and reception in refugee camps, helping to re-establish social structures,and settling new arrivals on small plots if there is land available. Even though one sees a lot of landin Dadaab, the permission to use it is contested. The host and older refugee communities need largetracts of the arid land for their animals’ grazing, and this is often their only livelihood. Still, comparedto conditions in Somalia, Dadaab is heaven, a place where refugees can live peacefully, wherethey can restore their hope.In <strong>2008</strong>, our work became easier and morechallenging in various ways.After many years of hard work, often personallyby Dr. Ishmael Noko, General Secretaryof the overall LWF, LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> signedan agreement with the Government of <strong>Kenya</strong>that exempts the organisation and internationalstaff in <strong>Kenya</strong> from paying taxes and import duties.This means that LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> can reducesome of its personnel and equipment costsfrom March <strong>2008</strong> forward, and there could beimplications for staff costs prior to that. Theagreement also covers LWF/DWS as a regionaloffice, which could theoretically have advantagesto surrounding programmes.Despite this long-sought-for tax developmentin <strong>2008</strong>, it was also necessary to further reducecosts and overheads, which resulted in someinvoluntary staff terminations in the projects.This was especially the case in Kakuma becauseof a reduction in the task load there and an evenmore drastic corresponding reduction in thatproject’s budget, as well as in Nairobi in orderto stay in line with programme trends. However,by the very end of the year it became clear thatthe <strong>Kenya</strong> government would not make moreland available for Somali refugees in Dadaab, announcingthat 50,000 refugees would be movedfrom there to Kakuma, setting the stage for a reevaluationof the whole picture in 2009.When budget revisions like those that occurredin <strong>2008</strong> are necessary, overheads tend tosuffer first, which threatens project implementationand administration. It is always a greatstruggle to keep administration costs low, eventhough everyone believes administration oversightis important, as cheap in the short-termcould mean expensive in the long-term. If thereare not enough controls in place or if there isinsufficient capacity to carry out ever-increasingtasks, situations of mismanagement could arise.LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> is fully aware that all itswork is under the mandate of the Governmentof <strong>Kenya</strong> and UNHCR. Within that mandatewe find many friends to work with us. We arenot just the LWF’s arm in <strong>Kenya</strong>, but we are allof us that care: our related agencies and theirdonors, and all the people therein; the host andrefugee communities and their individual members;and the staff of all agencies. We want to assureeveryone that the work LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>is doing is excellent, with great, committed staff.We are providing Hope InDeed.Philip WijmansLWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> Representative2Photo courtesy of Philip Wijmans

<strong>Kenya</strong> Country ProfileLake TurkanaKakumaAreatotal 582,650 sq kmland 569,250 sq kmwater 13,400 sq kmlength of coastline 536 kmLand useTurkana DistrictRIFT VALLEYarable land 8.01%permanent crops 0.97%other 91.02% (2005)PopulationDadaabtotal 37,953,840growth rate 2.758% (<strong>2008</strong> est.)Infant mortalitytotal 56.01 deaths/1,000 live birthsmale 58.95 deaths/1,000 live birthsfemale 53.02 deaths/1,000 live births(<strong>2008</strong> est.)Life expectancy at birthtotal population 56.64 yearsmale 56.42 yearsfemale 56.87 years (<strong>2008</strong> est.)HIV/AIDSpeople living with HIV/AIDS 1.2 million(2003 est.)prevalence in adults 6.7% (2003 est.)deaths 150,000 (2003 est.)Literacy rate (age 15 and olderwho can read and write)total population 85.1%male 90.6%female 79.7% (2003 est.)EconomyGDP per capita purchasing power parity$1,700 (2007 est.)population below the poverty line 50%(2000 est.)unemployment 40% (2001 est.)labour force in agriculture 75%Rank on U.N. HumanDevelopment Index:148 (2005)Source (unless indicated): CIA World Fact Book <strong>2008</strong> –www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ke.htmlPhoto by Annu Kekäläinen3

DADAABRefugee Assistance ProjectManaging the Dadaab Camps,Keeping People – and Hope – AliveAnne Wangari, Project Coordinator of theDadaab refugee camps for LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>,says there are many challenges she and LWF/DWS face in their management roles in thecamps. Many of the challenges are daunting orsimply out of their control, especially becauseLWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> began its work in the campsso long after they were established and over theyears many areas of the camp have become disorganisedand have fallen below standards. Speakingon the morning before important electionsof refugee leaders in the camps (see related story)in October, Wangari looked back at what LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> had been able to accomplish in<strong>2008</strong>, on a day that also began LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>’ssecond year of work in the Dadaab camps.Wangari described the year as “tough” and“challenging,” yet noted that LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>had achieved a great deal. Much of its accomplishmentsmight not be seen now, she said, asLWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> had spent most of the yearonly laying the foundations and putting structuresin place to make its more visible work inthe coming years easier. Among the notable accomplishmentsin these areas were mobilisingthe camps’ residents for leader elections, andWangari said that the physical layout of thecamps was being improved and that there werefewer security incidents to deal with.In its preparatory work, Wangari was mostproud of the fact that LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> wasto begin moving, later in the month she wasspeaking, some of its staff into the camps themselves,rather than being based in one centralcompound. This was going to allow LWF/DWS<strong>Kenya</strong> to address the many issues relating to landand space and make it more readily available tothe needs of the refugees. Another achievementworth noting, Wangari said, was LWF/DWS<strong>Kenya</strong>’s part in receiving an influx of asylumseekers through Liboi, a border town. With newarrivals, “we have again been at the forefront ingiving plots to all new arrivals until mid-August.After that, there was no more land for plots,” shesaid. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> has provided new arrivalswith mats, jerry cans, soap, blankets and othernon-food items, even before they were registeredby UNHCR, according to Wangari.One factor in the situation remains out ofthe control of LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>. There is notmuch hope for Somalia in the near future, Wangarisaid. There is no talk at the moment of resettlingrefugees in Dadaab in a third country orof reintegration. Therefore, she sees LWF/DWS<strong>Kenya</strong>’s presence in the Dadaab camps beingnecessary for at least several more years. vREFUGEE POPULATION FIGURES(all are estimated)• Total population of the three campsin Dadaab: 216,000 (about the sizeof Des Moines, Iowa, in the UnitedStates or Southampton, U.K.)• Ideal population of each camp:30,000• Population of the largest camp(Hagadera): 80,000• Approximate number ofspontaneous arrivals per day: 200• Number of families awaiting plotassignments: 6,000-8,000• Ideal density of each block in camps(according to Sphere standards):120 families• Current density: 600 families4Photo by LWF staff

clearing the way forBETTER LIVING CONDITIONSOne part of the provision of services by LWF/DWS<strong>Kenya</strong> to residents of the three camps in Dadaab isoverseeing the layout of the camps. A major partof physically organising the camps is ensuring thereare good roads that enable all parties, from refugeesto organisations providing camp services, to get intoand around the camps easily and efficiently. See thebox below for other challenges that this sector faces.UNHCR mandated LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> to improvemajor roads within the Dadaab refugeecamps in October 2007. An assessment of theroads revealed that most of the 157 kilometresof major roads had been encroached upon, narrowedor blocked by unsanctioned shelters, latrines,livestock fences and vegetation.Not only was everyday navigation and accessibilityto various important places within thecamps difficult, but delays in reaching refugeesin disaster and emergency responses were havingdevastating consequences, especially in outbreaksof fire, sudden epidemics and delivery ofemergency services.UNHCR approved a budget for improving20 major access roads (26 kilometres) in <strong>2008</strong>. Inaddition, the Church of Sweden (CoS)/SwedishInternational Development Agency (SIDA)funded improvements for 18 additional accessroads (24 kilometres), 18 road tags and labels, andshelter/toilet relocation assistance for 170 units.LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> conducted several meetingsand awareness sessions with refugee leadersbefore the road improvements began, but itfailed in getting their full commitment and support.As much as the leaders acknowledged theimportance of clearing the roads, they were notPhoto by Sofia Malmqvisthappy because some shelters and latrines werelocated on future roads (road reserves) and hadto be demolished.The assistance of CoS/SIDA in relocatingshelters and toilets was a powerful bargainingand negotiating tool to get support from therefugee community. But it was not over yet. Theactual commencement of the work in Hagaderacamp faced further difficulties. In some cases,the measurement and demarcation of road reserveswere regularly stopped by protesting communitymembers. During nights and weekends,the markers defining the road reserves were continuouslyuprooted, which meant the work hadto be re-done.LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> sought the interventionof UNHCR. This resulted in a pilot project onone road that involved marking and clearing theroad at the same time. This was done after realisingthat it was not possible to secure supportfrom everybody. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> needed toshow some determination, seriousness and firmnessto succeed among the Somali community.UNHCR provided its earthmoving machinethat cleared fences and demolished latrinesthat were encroaching on the road immediatelyafter the road was marked. Followingthe pilot project, there was immense success andsupport in the clearing of the subsequent nineaccess roads.LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> partnered with theNorwegian Refugee Council (NRC) for materialand technical support in latrine relocationand replacement. NRC provided quotations forlatrine construction, after which LWF/DWS<strong>Kenya</strong> settled on procurement and distributionof sacks and/or digging pits as part of its assistance.NRC also collaborated with LWF/DWSthe rubber meets the roadin one LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> staff member<strong>Kenya</strong> on raising awareness of the relocationof latrines immediately after the road demarcationand prior to clearance and gradation ofthe roads. As of September <strong>2008</strong>, 8,580 sackshad been distributed to reconstruct 132 affectedlatrines in Hagadera camp. It was anticipatedthat more families would be assisted than wasbudgeted for.The refugee community agreed to reconstructtheir own temporary shelters, leaving LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> to assist in the relocation of mudbrickshelters only. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> workedtogether with UNHCR, NRC and the communityto achieve this. Fifteen mud-brick shelterswere earmarked for assistance. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>also secured the technical support of <strong>Kenya</strong>’sMinistry of Roads in improving the roads.All in all, the working partnership amongUNHCR, NRC, refugees and the Governmentof <strong>Kenya</strong>, complemented by assistance from theChurch of Sweden in relocating shelters, toiletsand fences, made improving the roads a successin the Dadaab refugee camps. v– By Samuel Ouma, LWF/DWS Camp PlanningOfficer, DadaabTIMELINEYear camps were established in Dadaab:1990Time LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> began its work incamps: October 2007When it comes down to it, Elizabeth Akello is the one who has to deal directly with the pressure forspace in one of Dadaab’s camps. In other words, for finding new refugee arrivals a living space orclearing passageways among them, Akello is where the rubber meets the road, as the saying goes.As the Camp Planning Assistant for LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> in Hagadera camp, Akello functionsas accommodation finder and city planner, roles that range from assisting individuals orfamilies to making decisions that could affect tens of thousands of camp residents. She wasinvolved in the first major clearance of roads (see main story), helping to mobilise the communitiesin the camps in support of the project. When her efforts to get the cooperation ofthe camp’s block and section leaders were unsuccessful, in a desperate attempt, she approachedsome of the camp’s religious leaders. She got a breakthrough when the Muslim leaders found apassage in the Koran that supported her argument for clearing the roads. “The religious leadershelped me a lot,” Akello said.(continued next page)5

Akello named the benefits of creating clearroads among the blocks of each camp:• accessibility for camp residents andoutside service providers• mutatu (public transportation) businessescan start up and thrive, whichcreates income and builds an economyin the camps• the distance camp residents have totravel between their houses and businessesis shorter• improved security; for example, thereare fewer places for thieves and attackersto hide along a straight roadwith no obstructions• communication is faster in an emergency,and a response to a fire, for example,is quicker• a vehicle taxi can be hired instead ofa donkey cart to take a patient to thehospital, for example, which is faster• water-delivery lines can be monitoredeasierAkello also described the dilemma she faces ona nearly daily basis. On one hand, as the personin charge of space, she is approached by many ofthe 200 people who arrive spontaneously in thethree Dadaab camps daily (despite the closedborder between <strong>Kenya</strong> and Somalia). “Whenthey come, there is no more space to demarcateand give out,” she said. These scores of familieshave been through an ordeal already – fleeingviolence in their home areas of Somalia, losing their homes, livelihoods and often family members,and travelling long distances to reach the refugee camps. They desperately want and need a spot torest, settle and take care of their basic needs. But with space so tight in Hagadera and the other twocamps, Akello’s first recommendation to these spontaneous arrivals is to find a relative or friend inone of the camps to live with in their existing space and home.Thus begins a vicious cycle. If these arrivals are able to find someone to live with, even temporarily,the population density of the camps rises quickly, and the pressure on the space and facilities mount.Families begin to move into open spaces, such as roads, plots planned for market areas, or even spacesoutside the legal boundaries of the camp which are owned and used by local residents. This sometimesbrings the refugees into conflict with the host community. This cycle increases the demands on Akello.“We are not able to monitor encroachment, which is part of our activities,” she said.Akello knows she has done her best. “I’ve played my part,” she said, explaining how she hasexhausted every possibility for accommodating new refugee arrivals while trying to maintain order inthe camp. The solution to the space issue, she said, needs to come from UNHCR, which as overallauthority in the camps and responsibility for the refugees. In the coming year, UNHCR was planningto open a fourth camp in the area to ease the pressure for space. vProviding Extra Protectionfor Special CasesOne area of the camps that LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> is managing is the “safe havens,” which are separate livingareas for refugees who need special protection. Their reasons for needing protection vary and can stem fromtheir situation before they became refugees, such as the country or tribe they came from or their social status,or something that has happened to them as a resident in one of the camps, as this example shows.Kimal came to Dadaab from Somalia six years ago. While he and his family (his wife, four childrenand 11 step-children) were at the transit centre of Dagahaley camp, he said he had become involvedin some trouble about ten days before.Kimal owns a small restaurant in the marketarea of Hagadera camp, and because thepolice knew that he had been a radio operatorback in Somalia, they approached him to helpthem retrieve a stolen police radio. The policeasked him to help investigate the theft by goingto the market and asking for a radio. Aftertwo days, two men came to his restaurant andsaid they had the perfect radio for sale, so Kimalwent with them. He saw that the radio was theone that had been stolen from the police, and heagreed on a price with the men. He went backthe next day, but instead of bringing money,he brought seven police officers with him. Thetwo men were arrested, but five more who hadbeen working with them were still not identified.Kimal was asked to return to the market andfind them. He was afraid of the men, but felt heshould obey the police. He didn’t tell his wifeanything because he wanted to protect her. Kimalwas able to find the five other suspects, whowere arrested. But then trouble arose as friendsof the suspects came after him. He went to thepolice, who sent him to the UNHCR ProtectionOffice, which referred him to the DagahaleyTransit Centre. v– By Sofia Malmqvist, Coordinator for the SomaliRefugee Programme6Photos by Sofia Malmqvist

Organising Elections and Camp Residentsto Foster Better RelationsProbably the biggest task that LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> undertook in <strong>2008</strong> was organising the elections of therefugee leaders in all of the camps, which took place in October. These elections served many purposes, includinggiving camp refugees a greater voice in their affairs and self-determination by providing a continuingleadership structure; organising residents to more effectively carry out functions like communication ofimportant messages throughout the camps; and in a more indirect and less tangible but no less importantway, teaching the refugees something about democracy and proper governance. On the LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>side, the elections simultaneously involved many facets of its work in the camps, from organising residentsto go to the polls to coordinating the other non-governmental organisations that assisted with the elections.One candidate standing for the post of block (the divisions of the camps) leader described his role, whichexplains from a refugee’s perspective the function of the elections and the leadership structure in their livesin the camps.Ujulu Obang comes from the western region of Ethiopia. He fled his country in 2004 because histribe was being targeted for killings by the government and came to live in one of the Dadaab camps.In 2006, he was elected the leader of his block. This was before LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> took over managementof many parts of the camp, and elections for block leaders were conducted with block residentsvoting by queuing behind their favoured candidate. This sometimes caused problems amongresidents as voting was done publicly and residents’ choice of candidates was visible to all.According to Obang, as block leader, he has:• coordinated communication between the various humanitarian agencies, including LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>, that are working in the camp and the camp’s residents, voicing the needsand concerns of the refugees• helped to disseminate information from the agencies to his block’s residents• identified vulnerable residents to the agencies and followed up to make sure their needswere addressed• ensured the security of the community in cooperation with its elders and served as a representativeto the Government of <strong>Kenya</strong> or the agencies in these mattersIn the October <strong>2008</strong> elections, Obang was standingfor re-election in his position. Just before theelection, he had held a meeting with his block’sresidents at which he gave a report of his work asleader in the previous year. “They are very pleasedwith the services I have given them these years,”he said, confident of his re-election. In additionto having occupied the post before, Obang hasgained other experiences that are similar to hiswork as block leader. With a good commandof English, Obang also works as a translator forUNHCR, a position in which he also serves as aliaison between an agency and refugees.Obang named some of the challenges hewas expecting to face if re-elected, which were expressedto him at the meeting of the block’s residents.Obang said residents complained that notall needy people are being served by the agencies.He also said that resources are scarce. He gavethe example of an agency asking him to identifyonly five vulnerable people for a particular typeof assistance that as many as 1,000 may need.In his plan for his next term, Obang saidhe would continue to encourage the communityto take advantage of the education that isavailable in the camps – to send their childrento school and not allow their education to lapsewhile they are refugees. “We need also for securityto be maintained,” he said, expressing thehope that the agencies will continue workingwith the refugees on this issue. “If there is nosecurity, life will be difficult.”LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> changed the procedureof voting to a secret ballot in which residentswere hidden from view and placed a slip of paperin a jerry can labelled with a photo of theirchosen candidate. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> encouragedcamp residents to vote with an awarenesscampaign that included broadcasting messagesin their language through speakers mounted ona vehicle that drove through the camps. v7

KakumaREFUGEE CAMPHelping Women Sew Seeds for the FutureRhoda Nyakoich arrived at Kakuma in 2003 asa refugee from Sudan. Her father died before shewas born, and her mother died when Nyakoichwas 14 years old. She supported her siblings andthe children of her older sister, who had alsodied, by brewing beer. She was forcefully marriedoff by an uncle at the age of 16 and thenhad four children.Upon arriving at the camp, she realizedlife wasn’t easy there either. She borrowed 3,000<strong>Kenya</strong>n shillings (US$39) from a neighbourto buy supplies to resume her beer brewing inorder to earn some money. This choice of livelihood,in addition to being illegal, is viewednegatively in <strong>Kenya</strong> because it attracts troublesomecustomers who visit a brewer’s house andoften use foul language and become drunk andunruly. In 2005 her husband returned to Sudan,married another woman and stopped communicatingwith Nyakoich.In 2006 she heard about the tailoring trainingthat was offered by LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> in thecamp. But interviews had already been conductedand trainees recruited. Nyakoich stubbornlyasked to be given a chance to take part in thetraining, and she stood firm until she was admitted.She attended the training in the morningbut continued brewing beer in the afternoon.She was a very hard worker and the best studentthroughout the training.After completing the training, Nyakoich’slife changed. At the end of the training, everytwo trainees are issued with a sewing machineto use for a year. For the first time in her life,Nyakoich had a skill other than brewing beerfrom which she could earn an income. In fact,since the training, she has been able to give upbrewing beer.When training in arts and crafts was addedin the camp, Nyakoich volunteered for fivemonths with no pay at the handicraft centreto train women how to sew, store trainingmaterials and sell finished items. She didher work diligently as she continued participatingin tailoring production work. Whenfunding became available for the position of assistantin the income-generating project, she becameemployed in a job that has changed her lifecompletely. Now as a full-time job, she supervisesthe production of arts and crafts items, attendsto customers in the shop where the items are sold,supervises the production of sanitary wear, andhelps in the procurement and supply of sodasfor the canteen at the income-generating projectcentre. The items she makes, such as stuffed animalsand patchwork bags, are sold in the craftshop. After business hours, she continues workingto earn more income by sewing uniforms,underwear and women’s sanitary wear that areused by LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> in the camp.Nyakoich is now an empowered womanwho is a common figure around the LWF/DWS<strong>Kenya</strong> finance offices, where she goes to getchange for the operation of the income-generatingprojects or to push for payment for suppliesmade for other departments within the organisation.She can now afford to employ a woman todo her washing and cook for her children as sheattends to work. She is also able to comfortablypay the fees for all her children to attend the<strong>Kenya</strong>n schools outside the camp, which mostcamp residents cannot afford to do. She has justconstructed a new house for her family, and sheis saving money to buy a multipurpose sewingmachine with an aim of starting an embroiderybusiness. “Life now is better,” said Nyakoich.In an interview, Nyakoich spoke about howshe stood in her church and gave a testimonyabout how the tailoring training helped her moveaway from beer brewing. She also said she hasbeen tithing to thank God for changing her life.Nyakoich easily communicates in Kiswahiliand understands a bit of English but cannotwrite in English. She therefore hopes to startattending adult English classes soon. This willenable her to attend to clients at the showroom,write invoices and create reports.Late in <strong>2008</strong>, Nyakoich travelled to thecapital of Nairobi with other women in the artsand crafts training to sell their wares at a largeChristmas craft bazaar. She is among the manywomen who have benefited from the activitiesof the income-generating project that is operatedby LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>. LWF/DWS hopesto run the same types of activities in its genderprogramme in order to benefit more womenwho are at risk due to their vulnerability. v– By Hilda Thuo, LWF/DWS Kakuma GenderAssistant for Income-generating Activities8

helping children knowand defend their rightsAs a way of protecting children, who are a vulnerable category of refugees in Kakuma Refugee Camp, aswell as empowering them to enforce their own rights, LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> conducts training on the topicof children’s rights. It has found that an effective way of instructing children on their rights is to havechildren themselves spread the knowledge among their peers. Children’s rights clubs have been formedin the camp, and in <strong>2008</strong>, LWF/DWS Kakuma staff offered training for the leaders of these clubs.All 34 club leaders were trained in the three-day sessions. Thirty of the leaders then conducted atleast one sensitisation meeting on children’s rights with their club’s members at their monthly meetings.These trainings were an eye opener for children in the camp. The trained children’s rights clubleaders are not only making the clubs’ members aware of their rights, but they are also able to take alead role in protecting children’s rights. Tabitha Nyadeng (whose name has been changed to protecther identity) is one club leader whose experiences illustrate this well.Tabitha is a 15-year-old refugee who came to Kakuma in 2004 with her uncle, whom she has beenliving with in the camp. “My parents were shot in my presence, and it took me time to forget about thatincident,” she said. “Thanks to the LWF Child Protection Unit, which referred me to Jesuit RefugeeService for counselling, I was able to cope with my misfortune after a short duration of one year.”“Before I was elected a leader in 2007, I had no idea of what children’s rights were, and I only knewabout our Sudanese cultural practices, some of which I realised later did not respect children’s rights,”Tabitha recalled. “My election to a children’s rights club leaderposition was actually my turning point in my life.”Tabitha has been actively educating other childrenon their rights, although she said it has not beensmooth. “’Who is lying to you children that you haverights?’ are some of the comments that I came acrossin my effort to protect our rights,” she said. “However,I rarely hear them of late.”She said that after several training sessionsfor club leaders, “I can now stand firmly andadvocate for children rights.” She holds regularmeetings with members at which they discussissues affecting them as children. After somemeetings, she shares what she has heardfrom the discussions with a childdevelopment worker. “Ihave been reportingchild abuse casesto the LWFsecurityoffice whenever I come across one,” she said.A recent case was of a 17-year-old girl fromthe Sudanese Dinka community who was beingforced to marry a man much older than she was.The girl’s parents had already received a dowrypayment for her marriage. “I reported the case,and arbitration was done but all in vain,” Tabithasaid. “Eventually the young girl was taken tothe Jesuit Refugee Service safe haven for protection.I count this as one of my achievements forthe year <strong>2008</strong>.”The LWF Child Protection Unit has notedthat at least one-eighth of child abuse and childrelatedcases that are registered per month arereported by children themselves.Tabitha said she is happy that most childrenin the camp are aware of their rights. “Ihope that people will advocate for children’srights and fight all the harmful traditional practicestreasured by custodians of culture,” she said.“I will fight till the end until I see all children’srights have been respected!” vPhoto by LWF staff9

Upholding RIGHTS,Upholding HOPE“Human Rights for Women: Human Rights forAll” was the slogan that appeared all over theworld as human rights advocates took to thestreets with white ribbons either tied on theirwrists or pinned on their chests to show theirsolidarity and commitment to eliminating allforms of violence against women.The Kakuma community also took part inmarking this occasion. Human rights supportersand LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> gender staff joinedthe campaign on 25 November <strong>2008</strong>, the InternationalDay for the Elimination of ViolenceAgainst Women and the first of 16 days of worldwideactivism against gender-based violence thatended on International Human Rights Day.Violence against people, especially women,remains a challenge in Kakuma Refugee Camp.Governments have not fully implemented theHuman Rights Convention of 1948. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>, UNHCR and other implementingagencies, together with the Government of<strong>Kenya</strong>, continue to address this issue.Nyandeng (whose name has been changedfor her protection) is a refugee in Kakuma RefugeeCamp. Her situation is one among many inthe camp that stands as an example of genderbasedviolence and how LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> hasaddressed it.In 1991, Nyandeng fled her home countryof Sudan during its civil war with her motherand two sisters and went to Ethiopia. She wasraped on the way by an Arab soldier and gotpregnant. The next year, when she was only14 years old, she gave birth to a baby boy onemonth after their arrival in Kakuma RefugeeCamp. She had it rough in her communitywhen it was discovered that the child was anArab. Her relatives advised her to kill the child,but she refused. Later she was forced to marrya 65-year-old man and become his fourth wife.She tried to refuse, but her uncle threatened tosell her to the Murule, a tribe in Sudan, if shedidn’t give in. She was forced to marry the olderman because her country’s tradition would nothave allowed another single man to pay a dowryto marry her as a woman who had given birthout of wedlock. Only Sudanese women (fromthe Dinka tribe) who have been paid for with adowry are given respect in the community.In 2005, the husband Nyandeng had beenforced to marry died after an illness. His familydecided that she would become their property,but again she refused. The case was handledby a bench (traditional) court that decided shehad to be inherited or her children be given tothe husband’s family. She was uncomfortablewith this decision and reported her situation tothe LWF/DWS gender staff in Kakuma. Theycalled together all parties, including elders fromthe bench court, for an arbitration meeting.In 2006, her husband’s family wantedto marry off Nyandeng’s 13-year-old daughterto a boy who had resettled in America,but she refused and reported the case again.The perpetrators fled to Sudan when theyheard that the case had been reported.The daughter was taken to a girls’ primaryboarding school to enable her tocontinue her studies after several attemptsof abducting her failed.Nyandeng said it was her prayerthat her children excel in their studiesso that they can grow to challengethe harmful traditional practicesthat put women at risk. v– By Rita Mami, LWF/DWS KakumaGender Equity and HumanRights OfficerPOPULATION FIGURESAt beginning of <strong>2008</strong>: 60,578 peopleAt end of <strong>2008</strong>: 50,320 people (16.9percent reduction) (51 percent Sudanese,36 percent Somali, 9 percent Ethiopian,4 percent other)SOME FACTS ABOUT THESERVICES LWF/DWS PROVIDES INKAKUMA REFUGEE CAMPServices provided:• distribution of food and water• education• community services – includes:• gender equity and human rights• peace building and conflictresolution• refugee empowerment• sports and youth development• preschool, primary and secondaryeducation• vocational skills training• reception of newly arrived asylumseekers• combating HIV/AIDSFOOD FACTSLWF/DWS distributes food rations tocamp residents on behalf of the WorldFood Programme twice each month.Amount of food provided per person perday: 2105.146 kilocaloriesLWF/DWS distributed supplemental foodrations provided by UNHCR to provideaddition nutrition to recipients:• 275.908 metric tonnes of groundnuts (2,070 kilocalories)• 229.765 metric tonnes of greengrams (898 kilocalories)WATER FACTSAverage amount of water available toeach camp resident per day:• in 2007: 22.9 litres• in <strong>2008</strong>: 23.4 litres(Both figures are well above theSphere guidelines of 15 to 20 litresper person per day.)Average number of persons using eachwater tap:• in 2007: 103• in <strong>2008</strong>: 76The reduction is mainly due tothe falling camp population. Theincreased accessibility to water hada positive impact on hygiene andreduced incidences of communitymembers getting water from untreatedsources.EDUCATION FACTS2,320 girls in 1 boarding and 6 dayschools received uniforms that were madeby trained refugee women’s groups.15 primary schools received school suppliesin the first term, and after threeschools closed as a result of a decliningcamp population, the remaining 12 continuedto receive supplies.10

Living Conditions are Improvedby Improving Bicycle Taxi SafetyWith approximately 1,500 bicycle taxi operators, known locally as boda bodas, providing this serviceis a popular business in Kakuma Refugee Camp. The camp, inhabited by refugees and residents ofthe host Turkana District, covers an area of 21 square kilometres, which has created the right conditionsfor the supply and demand of a simple form of transportation that can also provide a smallincome for operators.The boda bodas are usually concentrated around the Somali community area, which is the commercialhub of the camp. They are operated by cyclists who come from the refugee and host communities.Most are between 16 and 25 years old.For a long time, these cyclists had no training on highway codes, traffic regulations, cyclingsafety, and first aid. Consequently, there were numerous bicycle accidents which at times resulted infatalities and fights and tension among ethnic groups. In 2007, approximately 12 bicycle accidentswere being reported every week, with approximately five deaths a year. The cyclists took no responsibilityfor their actions and often fled accident scenes without caring whether the victims wouldsurvive or not. Ethnic tensions stemming from accidents rose to their highest in March <strong>2008</strong> when athree-year-old refugee girl died as a result of a reckless host-community bicycle taxi rider.Concerns were often expressed about the negative health and social effects of irresponsibleand disorganised bicycle taxi operations around Kakuma. These concerns were raised at meetingsof community leaders and peace committees and at joint peace and security meetings. As a result,LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> identified the need for streamlining boda boda operations, and took the lead rolein doing this. While promoting the rights of the refugees and the host community, the objectivewas to create a safe transport system, reduce the incidents of communal/ethnic conflict and tensions,and enhance the livelihoods of local and host community youth. Ultimately, LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>intended to facilitate a process in which the <strong>Kenya</strong> government, the police, boda boda operatorsand customers, and the refugee and host communities at large all exercised their duties andresponsibilities in promoting security and safety, multi-ethnic coexistence, and protectinglivelihoods in and around Kakuma Refugee Camp.To do this, first LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> identified and invited all the relevant stakeholdersfor a brainstorming session on how to streamline boda boda operations. These included theDistrict Officer, who is the local government official in charge of security; the CommandingOfficer of the local police station, who oversees law and order; the LWF/DWS chief SecurityOfficer in charge of security in the camp; the LWF/DWS Peace-building and ConflictresolutionOfficer in charge of promoting peaceful coexistence; and representativesof the boda boda cyclists and community leaders. This session not only reflectedinterdependency among these actors, but also created a feeling of ownership of theinitiative by all the affected and interested parties.It was agreed that the first step was to create an association which all cyclistswould be required to join. The association was formed and registered with the government’sDepartment of Social Services, a constitution was prepared, and officerswere elected. The officers were then taken for an exchange and learning visit tothree other towns in western <strong>Kenya</strong> that have organised and active bicycle taxiassociations. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> facilitated a five-day training workshopfor 60 members of the association on the highway code.The topics covered included traffic signs and signals, generaltraffic offences and proper conduct of a taxi operator.The association was able register 645 boda boda operatorsas members. They were given registration numbersand number plates for bicycle taxi identification. Positiveresults have been reported and observed following the adoptionof the identification tags, with significant improvement in thesafety of boda boda customers and social harmony betweenrefugees and the host community. The problems associatedwith hit-and-run accidents are declining as a result of selfregulationmechanisms adopted by boda boda operators.The association has also identified routes and stations inthe camp where taxi riders are to operate on in order tolessen congestion and road obstructions. Route and stationsupervisors have also been appointed.Bicycle accidents have decreased to an average of four perweek. Roads have become safer, and there have been no ethnictensions created by boda bodas. More youth fromthe host and refugee communities have been attractedto the bicycle taxi business and are formingself-help groups to enable them to purchasebicycles to start and/or expand their businesses.On average, a boda boda operator earns a netincome of about US$4 per day, which is wayabove the average daily income of ordinary residentsof Turkana District, of whom more than70 percent earn less than one dollar a day.It is important to note that this was notthe first attempt to streamline the boda boda operations.Initial attempts by UNHCR and theLWF/DWS Kakuma security and peace unitsin 2006 and 2007 failed due to the approachthat was adopted – not involving all relevantstakeholders, such as the police, who are legallymandated to enforce traffic laws, communityleaders, and most importantly, the boda bodaoperators themselves. These earlier failures alsoposed serious challenges at the beginning of the<strong>2008</strong> attempt. The first two meetings were poorlyattended and had to be postponed.The lesson learned from the earlierattempts is that it is important toinvolve the relevant stakeholders inthe process right from the start. v– By Leah Odongo, LWF/DWSKakuma Peace Building andConflict Resolution Officer11

Turkana Districthost community projectSUSTAINING THE CORE LIVELIHOODSof the region’s residents12In <strong>2008</strong>, LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> continued itsemergency and development activities from theprevious year in the Turkana District, the hostcommunity of Kakuma Refugee Camp. Theseactivities largely addressed the factors that hadnegative impacts on the pastoral way of life,which is the main livelihood among host communityresidents. These factors are a shortage ofnatural water sources for animals and humans,insecure food supplies, and internal and externalsecurity incidents.Building on this core of support to residents’livelihoods, the Turkana project expandedits activities in <strong>2008</strong> (see related story). However,the original activities experienced their ownshare of challenges and successes.Turkana District is classified as a waterdeficitzone, and the drought which prevailedfor most of <strong>2008</strong> exacerbated the problem ofinadequate pasture and water for human andlivestock use. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> drilled fournew boreholes and rehabilitated three that hadbroken down. The gold-mining area receivedwater in tanks supplied by LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>early in the year. Repairs on a water pan at Nasekonawere also made. Pastoralists are also beingtrained to maintain these water facilities as aregular part of the work.Around the refugee camp, the only sourceof naturally occurring water is hand-dug wellsin a dry riverbed, which are shared by the hostcommunity and some refugees, sometimes resultingin conflicts. Another cause of conflictsare when pastoralists search for pasture andwater for their animals and cross internationalborders, encroaching on other pastoralists’ landand resources.LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> conducts peace-buildingand conflict-resolution activities to preventand settle these conflicts, leading to coexistenceamong the Turkana, refugees and communitiesacross the border in Uganda and Sudan.A major security incident occurred inAugust when some nomadic pastoralists wanderedinto Uganda, where they were bombed inOropoi Division. One person was killed alongwith more than 250 cattle and some donkeys.Livestock raids into Southern Sudan occurred,which resulted in the killing of pastoralists andthe abduction of Turkana children into Sudan.In a major success, however, some livestock wererecovered peacefully from Uganda as a result ofefforts led by LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> and intergovernmentalcollaboration.Pastoralists experienced many outbreaks oflivestock diseases, and LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>, in collaborationwith the <strong>Kenya</strong> government’s livestockdepartment, vaccinated 200,470 sheep and goatsagainst goat plague and 133,710 against caprinepleural pneumonia. Many animals were alsotreated and dewormed in the process. The twostores supplying drugs for livestock in Kalobeyeiand Letea received a new supply, and two new satellitedrug stores were started in the gold-miningarea and Lokangae. This improved the drug supplychain to the pastoralists. Pastoralists receivedtraining to help them better manage livestock diseasesand the drug supply chain. The training alsoincluded drought management strategies. vPhoto by LWF staff

helping a local economyadapt to changing conditionsThe relationship between Kakuma Refugee Camp and its host community in <strong>Kenya</strong>’s Turkana Districthas both positive and negative aspects. There has been both peaceful coexistence and conflict amongthe camp’s refugees and the permanent residents of the area. Despite this “love-hate relationship,” thecamp has, over the years, become a major contributor to the local economy of the host community.The trade between the two communities is estimated to be worth millions of <strong>Kenya</strong>n shillings.In the trade of livestock alone, before thousands of refugees began to return to Sudan after thesigning of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, and when the camp’s population was at itspeak of 90,000, an average of 80 goats was slaughtered in the camp daily. Goat is a common meat in<strong>Kenya</strong>, and most goat meat was sold to refugees by Turkana residents who had raised the animals. In<strong>2008</strong>, the average number of goats slaughtered daily had decreased to 45. At a cost of 2,000 <strong>Kenya</strong>nshillings (US$26) per goat, this meant a loss of 70,000 shillings (US$888) in income daily. Similarly,the slaughter and sale of cattle has decreased to two animals daily from a high of five, which is about50,000 shillings (US$634) of lost income.The host community has also lost employment opportunities and a large part of its market forother products, such as firewood and building materials, as the camp’s population has decreased.Although these economic losses have not been quantified in monetary terms, they have been feltnevertheless. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>’s Turkana project believed, therefore, that there was a need to createand develop income-generating activities to compensate for the lost income and that would exploitexisting opportunities outside the camp.Thus a sustainable livelihood-improvementproject was started in <strong>2008</strong>. While 60 percentof the host community relies on livestock forits livelihood and over the years LWF/DWS<strong>Kenya</strong> has been assisting residents in combatinglivestock diseases and providing water forthem, there has been a deliberate effort to diversify,develop and exploit other opportunitiesfor generating income and employment, especiallyfor youth and women. The components ofthe project are providing microcredit for smallincome-earning enterprises and helping peopledevelop new skills. These are aimed at providing(continued next page)13

the project’s participants with tools and resourcesto develop economic self-sufficiency.Some of the Turkana residents who arereceiving assistance from LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> insetting up micro-enterprises are pastoralists whohave lost their livestock to diseases or the frequentcross-border raids. With no way to continueearning a livelihood, these pastoralists faceextreme poverty, and so the micro-enterprise activitiesgive them a new way to be self-reliant.For income-generating activities, LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> helped residents form 11 groupsof about 25 members each. Members were chosenfrom three divisions in the district, with afocus on unemployed youth and women. LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> facilitated a process for the groupsto develop rules and regulations (bylaws) and toregister with the relevant government ministry(Social Services). The groups were then trainedon group dynamics, leadership, resource mobilisation,and business management. Finally, thegroups came up with business proposals thatwere reviewed by the project’s staff, and uponapproval the groups received capital supportfrom LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>. It disbursed amountsranging from 60,000 shillings (US$760) to206,500 shillings (US$2,617) to groups thatplanned to start small businesses such as groceryor retail shops or livestock trading.One group in Makutano, an area 70 kilometresfrom Kakuma, is buying goats to raisethat the group tries to sell at a higher price atthe livestock market in Kakuma. In December<strong>2008</strong>, it had purchased 30 goats and had sold24 of them a few weeks later, earning a profit ofseveral thousand shillings. Jeremiah Epao, whowas elected secretary of the group during the organisingphase, said that members had learnedvarious lessons. He said members had benefittedfrom the training in business practices, seeingthe value of investing their personal funds as wellinto the group’s activities, which will hopefullybenefit each of their families through the profits.But the group was also seeing the value of beingtogether, discussing ideas, and benefitting fromdoing something in a group which could not berealised by individuals acting alone.The challenge for the future is how thegroups can sustain themselves, especially whenLWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> stops its support. As a wayforward, the project involved the relevant governmentministries and agencies and expectsthat they will continue supporting the groupsin the future.To facilitate the learning of new skills,LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>, together with the communitiesand local leadership, identified 12 peopleto learn hairdressing and beauty skills and 20people to undergo computer training. Participantsin the former received training over threemonths and now have marketable skills in haircuttingand styling and giving manicures, pedicuresand massages. The majority of participantsin the computer training are young people whohad recently completed their secondary education.Their new skills in typing and in MicrosoftWindows, Word and Excel will hopefully bringthem to the competitive level in the job market.By the end of <strong>2008</strong>, these groups and individualswith new skills were trying out what theyhad learned. It is hoped that more employmentopportunities are being created, incomes are beingimproved, and that the impact of a shrinkingrefugee camp population is being mitigated. v— By Owen M. Karong’e, Project Officer for theLWF/DWS Turkana project14

Protecting Young PeopleFROM A DEADLY VIRUS<strong>Kenya</strong>’s burning.From the virus, the HIV virus.Stop the menace.Tell the message about the virus.– Anti-HIV/AIDS song composed by studentsIn <strong>2008</strong>, the LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> project in TurkanaDistrict expanded its activities beyond itscore livestock, water, peace-building and conflict-resolutionactivities. In addition to helpingTurkana host community residents start smallincome-earning enterprises (see related story),the new activities also address HIV and AIDS inthe district. Kakuma, for example, has an HIV/AIDS prevalence rate of about 2 percent. Theproject has chosen to work with primary schoolsin addressing the pandemic locally in order tostart getting the message to young people at anearly age, which can hopefully slow the spreadof the disease.Kalobeyi Primary School, in the village ofKalobeyei, a short drive from Kakuma RefugeeCamp, is a school that benefited from theproject’s initial HIV/AIDS activities in <strong>2008</strong>.The village is no stranger to LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>.It is the site of a store and dispensary for livestockdrugs that the LWF/DWS Turkana projectestablished, and it has received other assistancefrom LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong>.The school’s head and deputy head teachers,along with two other teachers, received trainingstarting in August. The knowledge gained fromthe training is used to train other teachers andstudents on how to deal with HIV and AIDS.A government-issued curriculum for schools isused, and the process includes training peer facilitators– students who are equipped to talk totheir fellow students about the disease. This isespecially important as children often receive information– some of it false – from their friends.One purpose of the training is to dispel mythsabout HIV and AIDS that children also learn intheir villages and from their families.“LWF has done a great job,” said NgipuoBernard, head teacher.In the training, the students are given informationthrough songs, poems and plays.They even write their own compositions andcreate drawings with messages of prevention.Demonstrating a message they can deliverin a song, a classroom of students sang:Abstain from sex if you want to live.Secure your body until marriage.Your body is the temple of the Lord.And a poem they composed to share their viewon HIV and AIDS includes the words:AIDS, AIDS,What we want is life…Let’s fight AIDS…Abstinence is our weapon. vSOME FACTS ABOUTTHE ACTIVITIES LWF/DWSKENYA CARRIES OUT INTHE TURKANA DISTRICTACTIVITIES FOR:• water supply and management• livestock care and management• peace building• food securityFACTS ABOUT WATER SUPPLYAND MANAGEMENT• 4 boreholes were drilled andequipped with hand pumps.• 3 boreholes were rehabilitated.• 5 hand pumps were repaired.• 40 technicians and 6 water usercommittee members were trained.FACTS ABOUT LIVESTOCK CAREAND MANAGEMENT• 2 satellite stores to supply livestockdrugs were opened.• 30 animal health workers wererecruited from the community andwere trained and equipped.FACTS ABOUT PEACE BUILDING• 1 workshop was conducted for jointpeace and security committeemembers.• 1 joint peace-building workshop wasconducted among refugees and hostcommunity members.• 6 peace committee meetings wereheld across the three divisions of thedistrict to discuss peace, especiallyalong the border areas.• 12 village-based peace meetings wereheld in the villages neighbouring therefugee camp to discuss peacefulcoexistence among host communitymembers and the refugees.• 1 cross-border visit in which 40 localcommunity leaders from <strong>Kenya</strong> wentto Uganda was conducted. Grazingrights were discusses and agreedupon, and this reduced the grazingconflicts during the dry months ofMay to October.15

BEING READY TO RESPONDIN A SUDDEN CRISISThe disputed results of the presidential election in late December 2007 triggered sporadic violencein many parts of <strong>Kenya</strong> for several days into January <strong>2008</strong>. Riots and protests erupted, and gangs ofyouth were often responsible for perpetuating the violence. Members of certain ethnic communitieswere attacked, forcing them to seek refuge in police stations, church compounds and other perceived“safe” areas. The violence left more than 1,000 people dead and hundreds of thousands internally displaced.<strong>Kenya</strong>, which had played host to refugees from other countries for many years, had createdrefugees of its own citizens and within its own borders.In Teso District in western <strong>Kenya</strong>, the violence complicated an earlier situation of land clashes betweenthe Sabaot Land Defence Force (SLDF) and local communities. The SLDF had waged a brutaland bloody war against the communities that were resettled by the government in the Mt. Elgon area.The post-election crisis compounded this situation when the district had both displaced peoplereturning from the previous conflict and residents who were fleeing the new rounds of violence.Some families were ready to return to their ancestral homes but lost everything during thepost-election riots and violence. Others, such asbusiness owners, had nowhere to go when theirestablishments were looted and razed by lawlessyouth. Churches had been accused of takingsides in the election campaigns, and thus theirleaders were not perceived to be credible in mediatingor stopping the violence. Farming activitieswere greatly affected by the violence as majorhighways were barricaded, thus hampering thesupply chain of farm inputs. This caused furtherincreases in farm input prices after the violenceended, making it difficult for small-scale farmersto afford them.16LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> RespondsMembers of the global alliance of churches andrelated agencies Action by Churches Together(ACT) International responded from the beginningof the crisis by donating tents and kits ofessential supplies for internally displaced persons.It was noted, however, among ACT membersthat not all needs were being addressed inthe response.A few days after the violence and displacementbegan, LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> partnered withthe National Council of Churches in <strong>Kenya</strong>(NCCK) to provide assistance to the most venerablegroups in Teso District. Families that receiveddirect assistance were identified by thecommunity members themselves.In total, 449 displaced families receivedkits of essential household supplies. The kitscontained mosquito nets, blankets, kitchen setsand sanitary items. Maize flour, sugar, milk andbread were distributed to families and individualswho were staying in makeshift camps andpolice stations in the city of Kisumu. Financialassistance of about 2,000 <strong>Kenya</strong>n shillings(US$26) was given to families that had fledviolence-stricken areas and that were willing toreturn to their communities.Maize seed and fertilizer were distributedto 300 vulnerable farming families to help improvetheir food production. The recipients weresmall-scale farmers who could not afford thehigh-priced farm inputs. Some returnees whohad farms also benefited.LWF/DWS also facilitated an early psychosocialassessment mission, supported by theChurch of Sweden, which was later followedby a three-day psychosocial training sessionfor 35 pastors, counsellors, teachers, internallydisplaced persons and community leaders andthat was conducted in Malaba Town. The participantscame from the Teso, Malaba, Busia andMt. Elgon areas, which were adversely affectedby the crisis.A disaster-preparedness and managementtraining was prepared and was expected to beconducted in early February 2009 for ten LWF/DWS <strong>Kenya</strong> staff and five ACT <strong>Kenya</strong> Forummembers to help strengthen the organisationand the forum’s capacity to respond to and managedisasters.The ACT appeal for the response to the humanitariancrisis raised only about 20 percent ofthe targeted amount, and therefore proposed responseshad to be prioritised based on the mosturgent needs. vPhoto by Philip Wijmans

FINANCESIncome and Expenditure Statement for the year ended31 December <strong>2008</strong> (unaudited) (in United States dollars)Project Number Project Name/Donor Income ExpenditureStatement of Needs Projects09-4201 Kakuma Refugee Assistance Project 337,386 337,38609-4208 Turkana Recovery Project 64,743 64,743Emergency Projects (ACT appeals)402,129 402,12909-4420 ACT Appeal AFKE81 – LWF Assistance to IDPs in Teso 72,794 72,79409-4423 ACT Appeal AFKE73 – Emergency Preparedness to ReceiveSomali Refugee Influx in DadaabOther Projects75,508 75,508148,302 148,30209-4418 Church of Sweden – Assistance for Somali Refugees in654,225 654,225<strong>Kenya</strong>09-4624 UNHCR – Assistance to Refugees in Kakuma 1,501,022 1,501,02209-4635 Lutheran World Relief (LWR)/U.S. Bureau of Population,396,615 396,615Refugees and Migration (BPRM) – Kakuma Refugees09-4640 GTZ (German Development Corporation) – Community18,274 18,274Peace and Security Team (CPST)09-4648 World Food Programme – Food Distribution in Kakuma 138,200 138,20009-4651 DanChurchAid (DCA)/Danida – Kakuma-Turkana 1,006,423 1,006,42309-4656 World Food Programme 136,452 136,45209-4657 UNHCR – Voluntary Repatriation of Sudanese Refugees 201,940 201,94009-4661 Australian Lutheran World Service – Kakuma Refugee212,440 212,440Camp09-4665 DCA/SCOUTS Rays of Hope Kakuma (1,843) (1,843)09-4666 UNHCR – GLIA 31,484 31,48409-4670 FinnChurchAid – Support for Reintegration of Refugees133,182 133,182Returning to Southern Sudan09-4671 UNHCR – Emergency Assistance for Refugees in Dadaab399,173 399,173Camps09-4672 UNHCR – Liboi-Emergency Assistance New Somali Arrivals337,209 337,209Dadaab09-4673 LWR/BPRM – Somali Refugee Assistance in <strong>Kenya</strong> 65,660 65,66009-4674 UNHCR – Dry Borehole Rehabilitation, Kakuma Refugee201,756 201,756Camp5,432,212 5,432,212Other Projects - not managed by LWF <strong>Kenya</strong>09-4801 A Mother's Cry for a Healthy Africa 40,285 40,28509-4802 Third Summit and Pre-summit for Youth 2,288 2,28809-4803 Interfaith Action for Peace in Africa (IFAPA) – Nairobi50,701 50,701Office09-4804 IFAPA Youth Activities 21,361 21,36109-4810 Churches Ecumenical Action Sudan Crisis Management20,450 20,450Team135,085 135,085Totals 6,117,728 6,117,72817

Donors in <strong>2008</strong>(in United States dollars) (unaudited)Cash donations through GenevaAustralian Lutheran World Service 212,440Canadian Lutheran World Relief 702Caritas 10,475Church of Sweden 686,552DanChurchAid -1,843DanChurchAid/Danida 1,006,423Disciples of Christ Week of Compassion 2,990Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 260,652Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada 30FinnChurchAid 295,467GNC-HA Deutscher Hauptausschuss 14,743Lutheran World Relief 15,000Lutheran World Relief /U.S. Department of State 462,275Matsuki Suguru-Wakachiai 5,000Mennonite Central Committee 9,975Methodist Relief & Development Fund 38,536Other international donors 3,030United Church of Canada 15,1353,037,582Funds Received LocallyGerman Technical Cooperation 18,274Transfers from LWF Geneva for IFAPA projects 93,275Trust Africa 21,361United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 2,672,584World Food Programme 274,6523,080,146Total 6,117,72818Photo, top right, courtesy ofLWF German National CommitteePhoto, centre right, by LWF staff

STAFFName of Staff Nationality Position Name of Staff Nationality PositionNairobi – Head OfficePhilip Wijmans Dutch Country RepresentativeSarah PadreAmerican Finance ManagerTulasi Sharma Nepali Refugee Programme ManagerSofia MalmqvistSwedish Programme CoordinatorNancy Elizabeth <strong>Kenya</strong>n Office AdministratorDonald Magoba <strong>Kenya</strong>n Network AdministratorMoses Andalo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Office ClerkJoseph Oduor <strong>Kenya</strong>n Transport SupervisorJane Macharia <strong>Kenya</strong>n Office ReceptionistWashington Onyango <strong>Kenya</strong>n Office OrderlyLuka Kibande <strong>Kenya</strong>n Gardener/Cleaner/DriverNjeri Makumi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Deputy Finance ManagerGeorge Kirungi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Senior AccountantSamuel Gitau <strong>Kenya</strong>n Asst. Finance ManagerRosemary Mugalla <strong>Kenya</strong>n Cashier/AccountantKillion Ooko <strong>Kenya</strong>n Logistics & Procurement OfficerJack Kisero <strong>Kenya</strong>n Procurement OfficerJoy Ikiara <strong>Kenya</strong>n StorekeeperLavendah Okwoyo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Programme Development OfficerAlex Malome <strong>Kenya</strong>n Programme AssistantLokiru Matendo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Programme OfficerAnthony Njiru <strong>Kenya</strong>n Procurement & Admin Asst.Dadaab Refugee Assistance ProjectAnne Wangari <strong>Kenya</strong>n Project Coordinator (from June)Felida Asaava <strong>Kenya</strong>n Project Coordinator (until March)Samuel Ouma <strong>Kenya</strong>n Planning OfficerAlfred Ngonga <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security OfficerPeter Maina <strong>Kenya</strong>n Administrator/Finance OfficerLillian Kilwake <strong>Kenya</strong>n Camp Management OfficerJoseph Ikalale <strong>Kenya</strong>n Camp Management OfficerMahatho Biriye <strong>Kenya</strong>n Matron Officer – Safe HavenLeila Issack <strong>Kenya</strong>n Administrative AssistantGoefrey Kamau <strong>Kenya</strong>n AccountantJackson Lowoi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Construction SupervisorMohamed Noor <strong>Kenya</strong>n Head DriverMohamed Ali <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverMohamed Bare <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverOmar Badula <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverDouglas Mwirigi <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverFatuma Hassan <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security AssistantMuhiyadin Abdi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security AssistantBeverlyn Nyagule <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security AssistantElizabeth Akielo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Planning AssistantGoerge Wasonga <strong>Kenya</strong>n Planning AssistantJoshua Kinyua <strong>Kenya</strong>n Planning AssistantNasibo Abdi <strong>Kenya</strong>n CleanerOmar Ali <strong>Kenya</strong>n CleanerAbiwahab Ahmed <strong>Kenya</strong>n Camp Management OfficerAbdirahman Aden <strong>Kenya</strong>n Camp Management OfficerMaryan Hassan <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security AssistantBenard Langat <strong>Kenya</strong>n Planning AssistantMeah Sirinji <strong>Kenya</strong>n Reception Centre OfficerTurkana ProjectMichael Esang’ire <strong>Kenya</strong>n Project CoordinatorOwen Mangua Karonge <strong>Kenya</strong>n Project OfficerHellen Lipo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Community Development Asst.Imuton Joseph <strong>Kenya</strong>n Community Development Asst.Abdullahi E Lokidongo <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverBoniface Amorock Loyan <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverKakuma Refugee CampWilliam Wawire Tembu <strong>Kenya</strong>n Project CoordinatorGodfrey G. Muthithi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Human Resources OfficerPatrick Kibet Cheruiyot <strong>Kenya</strong>n IT AssistantEsther Akinyi Ochieng <strong>Kenya</strong>n SecretarySalome Asibitar <strong>Kenya</strong>n SecretaryJoseph Siekisa W <strong>Kenya</strong>n Maintenance SupervisorWalter Kipkebut <strong>Kenya</strong>n ElectricianHellen Nabuin Kowot <strong>Kenya</strong>n Office MessengerMary Akal Tioko <strong>Kenya</strong>n Compound CleanerJames Lowosa Eome <strong>Kenya</strong>n JanitorJames Nganga Kamau <strong>Kenya</strong>n Finance OfficerEunice Mungai <strong>Kenya</strong>n AccountantTonny Munga Mwaura <strong>Kenya</strong>n Asst. AccountantFarug Fadhil Bisbas <strong>Kenya</strong>n Chief Security OfficerEdward Lumumba <strong>Kenya</strong>n Asst. Security OfficerJackson Lomer <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security GuardMargaret Akiru <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security GuardLorine Atieno Oduar <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security GuardFrancis Nakwawi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security GuardDavid Kiptanui Korir <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security GuardEunice Jerop <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security GuardMackenzie Esin AkuutaSecurity GuardFina Thomas <strong>Kenya</strong>n Logistics OfficerNancy Mwaniki <strong>Kenya</strong>n Procurement AssistantFrancis Ewesit Esimit <strong>Kenya</strong>n Store SupervisorRespar Lilian Ookot <strong>Kenya</strong>n Procurement ClerkJulius Lisimba Mavisi <strong>Kenya</strong>n MechanicHosea Edung Echwa <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverJoseph Kamau Muhu <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverJoseph Wangalwa Okumu <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverDouglas Mwirigi Nkanata <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverAlfred Otieno <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverJonathan Chambai Kibet <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverJoseph Ikalale Imoni <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverDandon Ekai Ekaal <strong>Kenya</strong>n DriverElim Lokisiau <strong>Kenya</strong>n TurnboyEsau Wafula <strong>Kenya</strong>n Distribution C.Supervisor.Lucy Njambi Muraya <strong>Kenya</strong>n Distribution C.Supervisor.Simon Wamalwa Masinde <strong>Kenya</strong>n FDP Stores SupervisorPeninah Akuru Ebuke <strong>Kenya</strong>n FDP Stores SupervisorLeah Odongo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Senior Community Services &Dev. OfficerRita Mamai <strong>Kenya</strong>n GEHR OfficerGeorge Omondi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Youth Dev. & Sports Officer-AG SCDSO19

Name of Staff Nationality Position Name of Staff Nationality PositionGeorge Chemkang <strong>Kenya</strong>n Youth Dev. & Sports AssistantFrancis Namuya <strong>Kenya</strong>n P.B.C.R.AsstHilda Thuo Wangari <strong>Kenya</strong>n GEHR Assistant – IGAEmily Soup <strong>Kenya</strong>n Child BID AssistantMagdalene Wanza Muoki <strong>Kenya</strong>n Asst. Child Protection OfficerZedekiah Omutayi Chitayi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Senior Water OfficerMohamed Noor Hassan <strong>Kenya</strong>n MechanicEdward Wanyenya <strong>Kenya</strong>n PlumberNalioki Nalukoowoi Joh <strong>Kenya</strong>n Assistant PlumberLorot Agnes Ekutan <strong>Kenya</strong>n Store KeeperJulius Losekon Munyen <strong>Kenya</strong>n Pump OperatorReuben Mandila <strong>Kenya</strong>n Pump OperatorDavid Wanyonyi Chemkan <strong>Kenya</strong>n Pump OperatorTonny Ekuwam Ikone <strong>Kenya</strong>n Pump OperatorBoniface Mwangi Munyau <strong>Kenya</strong>n ElectricianNoreen Chebet <strong>Kenya</strong>n Social WorkerLawrence Karanja <strong>Kenya</strong>n ClerkFredrick Tati Adeya <strong>Kenya</strong>n Security GuardMichael Ejikon Lopeto <strong>Kenya</strong>n ClerkJoy Judith Khangati <strong>Kenya</strong>n Asst. Project Coordinator/Senior Education OfficerCollins Otieno Onyango <strong>Kenya</strong>n Education OfficerNick Lokitela Lomoruka <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherAemun Francis Lore <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherCosmos Orte <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherSirach Nanyangkot Mwanika <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherLucy Mugure Kithinji <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherKiprotich Rhoda Jerop <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherOduo Duncan <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherKiprotich Simion Kimutai <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherNgasike Benjamin Long’or <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherSabella Muthoni <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherJustine Onchiri Nyaribo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherLilian Cherotich <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherWaiyaki Joseph Waithanje <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherNalianya Anthony Nakweika <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherMonda Job Momanyi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherNgugi Martha Njoki <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherEric Akatu <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherEdward Koima <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherSharon Tinyilanga Imbala <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherFredrick Imbosa <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherVictor Lochee Emorut <strong>Kenya</strong>n Primary School TeacherGladys Edesa Muganzi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherHumphrey Ngai Wakithae <strong>Kenya</strong>n Head TeacherWamanyengo Gelas Namunyala <strong>Kenya</strong>n Head TeacherTuckson M. Kimathi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherJoseph Wekesa Namaulula <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherEdward Omondi Ondula <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherAdan Matet <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherOloo Rachel A <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherBoniface Gitonga Mwenda <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherLagat Irene Cheptoo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherMagicho Jackson Ogembo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherKimutai Emmanuel Kimaliel <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherNayanae Jeremiah Ewoi <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherIssa Efumbi Maungo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherRuth Ocheng Adoyo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherShadrack Onyango Owalla <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherDanson Kamau Gichinga <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherEdwin Rotich Githaka <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherOdhiambo B J Stephen <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherMige Jacob Odhiambo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherMargaret Wainaina <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherElsie Amollo Soita <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherAnnet Wanjira Kiura <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherHezron Kikwai <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherJoseph Odero Ojwang <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherKapis Odongo Okeja <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherVivian Khimwende Asman <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherLilian Wawire <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherLydia Kanini Muendo <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherTimothy Kithinji Gitonga <strong>Kenya</strong>n Secondary School TeacherWambui Kangethe <strong>Kenya</strong>n School Feeding ProgrammeField SupervisorAnna Ekutan Eleman <strong>Kenya</strong>n School Feeding ProgrammeAssistantJane Kemunto Mugaka <strong>Kenya</strong>n Copy TypistKimeli KimitaiLogisticsIsaac AgeviMozoni HarryGender OfficerJackson LowoiJohn EkamaisAndrew Loleel EkaranEducation OfficerRegina KiringoPrimary School TeacherEmanuel JumaHead TeacherMworia CarolinaDeputy Head TeacherPaul MwauraPrimary School TeacherMiriam LusicheSecondary School TeacherStephen KisorioSecondary School TeacherKevin MwangiSecondary School TeacherIsaac MainaSecondary School Teacher20Photos by LWF staff