1jjtwKx

1jjtwKx

1jjtwKx

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

36384042444648RANCHERS IN THE RAINFORESTIn Brazil’s Amazon region, the world’ssecond-largest herd of cattle meets theworld’s biggest rainforest. This is bad newsfor the forest. First come the loggers,then come the ranchers.THE GLYPHOSATE IN YOUR BURGERIf pesticides, herbicides or medicines leaveunwanted residues in meat, milk andeggs, we end up consuming them too. Gapsin research leave uncertainty aboutwhat glyphosate – a weedkiller used whengrowing genetically modified soybeans –does to our bodies. Legal loopholes mean wemay be eating it without knowing it.A PLETHORA OF POULTRY: CHICKENSTAKE THE LEADIn developed countries, consumptionof chicken is surpassing that of beef,and chicken production is nowhighly industrialized. Demand in Asia isrising fast, and people who refusepork and beef are happy to eat chicken.WHERE KEEPING CHICKENSIS WOMEN’S WORKMany women in Africa and Asia are forcedto be dependent on their husbands for bigdecisions. A few hens, chicks and eggs canbuild their confidence and self-reliance.Their contribution to the meat supply is oftenunderestimated.IMPORTED CHICKEN WINGS DESTROYWEST AFRICAN BUSINESSESEuropean poultry firms are not permittedto turn slaughter by-products into animalfeed. So they export them to developingcountries and sell them cheap. Broiler farmsin Ghana and Benin have gone bankrupt.DISQUIET IN THE DEVELOPED WORLDDemand for meat in the developed worldhas peaked, and is beginning to declineslowly. Consumers’ worries about food safetyare reinforced by scandals in theindustry. The industry is trying to improveits image with marketing ploys, butconsumers are confused and the product isnot necessarily any better.HALF A BILLION NEW MIDDLE-CLASS CONSUMERS FROM RIO TOSHANGHAIBrazil, Russia, India, China and SouthAfrica – the BRICS – are five big developingcountries that are setting out fromdifferent starting points. They may notend up with the food consumption patternsof the industrialized West.MEAT ATLAS505254565860626466URBAN LIVESTOCK KEEPINGFor many, urban livestock is acontradiction in terms. Isn’t livestock-raisinga rural activity, and don’t cities banlivestock because of the smell, noise andpollution? Yet urban livestock arecrucial for the livelihoods of many poor citydwellers. And they provide nutritiousfood at lower prices than their country cousins.TURNING SCRUB INTO PROTEINMuch of the world’s livestock, and much of itsmeat, milk and eggs, are raised bynon-industrial producers. Many of themmanage their animals on land that isunsuited for crops, optimizing the use oflocal resources. But the existence ofthese producers is under increasing threat.IN SEARCH OF GOOD FOODConcerned consumers in the rich world facea dilemma. They want good-quality meatthat is produced in an environmentallyfriendly, ethical manner. How best to ensurethis? Here we look at some alternatives.VEGETARIANISM: MANY ROOTS,MANY SHOOTSOnly a small percentage of the populationin the industrialized world describethemselves as vegetarians or vegans. Suchlifestyles are more common in partsof the world where religions play a majorrole. In most faiths, followers areexpected to abstain from meat in one wayor another.WHAT TO DO AND HOW TO DO IT:INDIVIDUALS AND GROUPSGiven all the problems with livestockproduction and meat consumption,is there anything that normal people cando? Yes: individuals can makechoices about their consumption patterns,and groups can push for change.A GREENER POLICY FOR EUROPEThe EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)has for decades supported, and distorted,farm production. It has evolved fromsupporting large-scale production to takingthe environment increasingly intoaccount. But problems remain. A greenerCAP could promote socially and ecologicallysound livestock production.AUTHORS AND SOURCESFOR DATA AND GRAPHICSRESOURCESAbout US26 topicsand 80 graphicson how we produceand consumemeat5

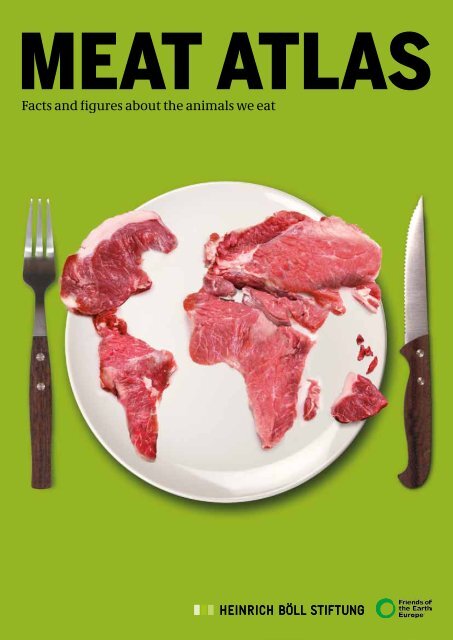

INTRODUCTIONFood is very personal. It is not just a need. Foodoften embodies certain feelings: familiarity,relaxation, routine, or even stress. We eat indifferent types of situations and have our own,very personal preferences.At the same time, however, we are more andmore alienated from what is on our plates, on thetable and in our hands. Do you sometimes wonderwhere the steak, sausage or burger you are eatingcomes from? Personal satisfaction reflects ethicaldecisions, and private concerns can be very politicalin nature. Each of us ought to decide whatwe want to eat. But responsible consumption issomething that an increasing number of peopledemand. Then again, they need information onwhich to base their decisions.How can normal consumers understand theglobal impact caused by their meat consumption?How many people realize that our demand formeat is directly responsible for clearing the Amazonrainforest? Who is aware of the consequencesof industrial livestock production for poverty andhunger, displacement and migration, animal welfare,or on climate change and biodiversity?None of these concerns are visible on themeat and sausage packages in the supermarket.On the contrary, big agribusinessestry to play down the adverse effects of our highmeat consumption. Advertising and packagingin developed countries convey an image of happyanimals on happy farms. In reality, the sufferingthe animals endure, the ecological damage andthe social impacts are swept under the carpet.„There are alternativesIn many countries, consumers arefed up with being deluded by theagribusiness. Instead of using publicmoney to subsidize factory farms – as inthe United States and European Union –,consumers want reasonable policiesthat promote ecologically, socially andethically sound livestock production.One in every seven people in the world doesnot have adequate access to food. We are a longway from realizing the internationally recognizedright to quantitatively and qualitatively sufficientfood. On the contrary, almost a billion people inthe world go hungry, largely because the middleclasses’ craving for meat creates large-scale, intensivelivestock and food industries.In many countries, consumers are fed up withbeing deluded by the agribusiness. Instead of usingpublic money to subsidize factory farms – asin the United States and European Union – consumerswant reasonable policies that promoteecologically, socially and ethically sound livestockproduction. As a result, a central concern of theHeinrich Böll Foundation is to provide informationabout the effects of meat production and tooffer alternatives.While governments in the developed worldhave to radically change course and struggleagainst the power of the agriculturallobby, developing countries can avoid repeatingthe mistakes made elsewhere. If they know aboutthe effects of intensive meat production, they canplan for a future-oriented form of production thatis socially, ethically and environmentally responsible.Instead of trying to export their failed model,Europe and the United States should attempt toshow that change is both necessary and possible.There are alternatives. Meat can be producedby keeping animals on pasture instead of in buildings,and by producing feed locally rather thanshipping it thousands of kilometres. Manure doesnot have to burden nature and the health of thelocal population; it can be spread on the farmer’sown fields to enrich the soil.Our atlas invites you to take a trip around theworld. It gives you insights into the global connectionsmade when we eat meat. Only informed, criticalconsumers can make the right decisions anddemand the political changes needed.Barbara UnmüßigPresident, Heinrich Böll Foundation6MEAT ATLAS

Food is a necessity, an art, an indulgence.But the global system for producing food isbroken. While people in some parts of theworld do not have enough to eat, others sufferfrom obesity. Millions of tonnes of food are wastedand thrown away, and perversely, crops are convertedinto biofuels to feed cars in Europe and theAmericas.At the same time, the natural world uponwhich we all depend is being damaged and destroyed.Ecological limits are being stretched asour demand for ever more resources takes precedenceover the need to protect biodiversity andthe Earth’s vital ecosystems. Forests and precioushabitats are being cleared to make way for vastmonocultures to supply industrialized countries.Farming is being intensified and wildlife wipedout at unprecedented rates.Over the past 50 years, the global food systemhas become heavily dependent oncheap resources, chemical sprays anddrugs. It is increasingly controlled by a handful ofmultinational corporations. The social impacts ofthis system are devastating: small-scale farmersworldwide are driven off their land, both obesityand food poverty are rife, and taxpayers and citizensare increasingly footing the bill for one foodcrisis after another. In this corporate-controlledfood system, profits always come before peopleand planet.Nothing epitomizes what is wrong with ourfood and farming more than the livestock sectorand the quest for cheap and plentiful meat. Manyof the world’s health pandemics in the past yearshave stemmed from factory farms. Livestock raisingis one of the biggest greenhouse gas emitters,and is responsible for the use of huge amounts ofthe world’s grain and water. Worldwide, livestockare increasingly raised in cruel, cramped conditions,where animals spend their short lives underartificial light, pumped full of antibiotics andgrowth hormones, until the day they are slaughtered.What is truly scandalous is that it doesn’t haveto be like this. We produce enough calories in theworld to feed everyone, even with an increasingglobal population. We know how to farm withoutdestroying the environment and without imposingcruel conditions on the animals we breed,without corporate-owned and controlled seedsand chemicals. Sustainable farming exists inwhich farmers produce meat and dairy productsfrom numerous smaller farms, grow their owncrops to feed their animals, and allow animals tograze freely.There are millions of local markets, and numeroussmall, innovative food companies. Thereis huge public support for sustainable farming:people are building an alternative global food systemthat is based on food sovereignty, and ensureseveryone’s right to safe, nutritious, sustainableand culturally appropriate food.There is increasing international recognitionthat the current industrialized and corporate-ledsystem is unsustainable and doomed to fail. Weneed a radical overhaul of food and farming if wewant to feed a growing world population withoutdestroying the planet. This system needs to havefood sovereignty at its heart.This publication sheds light on the impactsof meat and dairy production, and aims tocatalyse the debate over the need for better,safer and more sustainable food and farming. Wehope to inspire people to look at their own consumption,and politicians at all levels to take actionto support those farmers, processors, retailersand networks who are working to achieve change.As a species, we need to be smarter. It is time toacknowledge that the corporate-controlled foodsystem is broken. It is time to curtail the power ofthose vested interests that want to keep it. Revolutionizingthe way we produce and consume meatis just the start. We need to create a world wherewe use natural resources in a more efficient way.We need to ensure these resources are fairly distributed,and that everyone on this planet, bothtoday and tomorrow, has access to safe, sufficient,sustainable and nutritious food.Magda StoczkiewiczDirector, Friends of the Earth Europe„Catalyzing the debateThe current industrialized andcorporate-led system is doomedto fail. We need a radical overhaul offood and farming if we want to feed agrowing world population withoutdestroying the planet.MEAT ATLAS7

Lessons to learnAbout Meat and THe World1Diet is not just aprivate matter. Each mealhas very real effects on the lives ofpeople around the world, on theenvironment, biodiversity and theclimate that are not taken intoaccount when tucking into a pieceof meat.2Water, forests, land use, climate and biodiversity:The environment could easily be protectedby eating less meat, produced in a different way.High meat consumptionleads to industrializedagriculture. A fewinternational corporationsbenefit and furtherexpand their marketpower.43The middle classes aroundthe world eat too much meat.Not only in America and Europe, butincreasingly in China, India and otheremerging countries as well.5Consumption is rising mainly becausecity dwellers are eatingmore meat. Population growthplays a minor role.8MEAT ATLAS

Compared to other agriculturalsectors, poultry production hasthe strongest international links, ismost dominated by large producers,and has the highest growth rates.small-scale producers,the poultry and theenvironment suffer.67Intensively produced meatis not healthy – through theuse of antibiotics andhormones, as wellas the overuse ofagrochemicals infeed production.Urban and small-scale rurallivestock can make an importantcontribution to povertyreduction, gender equalityand a healthy diet – notonly in developing countries.1089Eating meat does not have to damagethe climate and the environment. Onthe contrary, the appropriate use of agricultural land byanimals may even have environmental benefits.Alternatives exist. Many existinginitiatives and certificationschemes show whata different typeof meat productionmight look like – onethat respects environmentaland health considerationsprovides appropriateconditions for animals.11Change is possible. Somesay that meat consumption patternscannot be changed. But a wholemovement of people are now eatingless meat, or no meat at all. Tothem it is not a sacrifice; it is partof healthy living anda modern lifestyle.MEAT ATLAS9

THE RISE OF THE GLOBAL MARKETThe developed world has fewer and fewer farmers, but they are keeping moreand more animals. Instead of producing for the local market, they supplydistant supermarkets. This same shift is now transforming livestock productionin the developing world.Pig and poultrymarkets aregrowing; beef andsheep markets arestagnatingOverall, the global demand for meat is growing,but at different rates in different regions.In Europe and the United States, thebiggest meat producers in the 20th century, consumptionis growing slowly, or is even stagnating.On the other hand, the booming economies inAsia and elsewhere, will see around 80 percent ofthe growth in the meat sector by 2022. The biggestgrowth will be in China and India because of hugedemand from their new middle classes.The pattern of production is following suit.South and East Asia are undergoing the same rapidtransformation that occurred in many industrializedcountries several decades ago. In the1960s in Europe and the USA, many animalswere kept in small or medium-sized herds ongrazing land. They were slaughtered and processedon the farm or in an abattoir nearby.Meat and sausage were produced in the same localityor region. Today, this mode of livestock productionhas almost died out. In the USA, the numberof pig raisers fell by 70 percent between 1992and 2009, while the pig population remained thesame. During the same period, the number ofpigs sold by a farm rose from 945 to 8,400 a year.And the slaughter weight of an animal has goneup from 67 kilograms in the 1970s, to around 100kilograms today.In China, more than half the pigs are still producedby smallholders. This is changing fast. Thesame technologies and capital investments thatdominate livestock production in the developedworld are penetrating developing countries – andthey are integrated in global value chains. Whena piglet is born, its fate is already sealed: in whichsupermarket, in which town, and with what typeof marketing its pork chops will be sold.But the production conditions are now verydifferent from before. Industrial livestock productionin Europe and the USA began when feed,energy and land were inexpensive. Nowadays, allthree are scarce and costs have gone up. As a result,total meat production is growing less quicklythan before. The market is growing only for pigsand poultry. Both species utilize feed well and canbe kept in a confined space. This means that theycan be used to supply the insatiable demand forcheap meat. By 2022, almost half the additionalmeat consumed will come from poultry.Beef production, on the other hand, is scarcelygrowing. The USA remains the world’s largest beefproducer, but the meat industry describes the situationthere as dramatic. For 2013, it expects a fallof 4-6 percent compared to 2012 and predicts thedecline to continue in 2014. In other traditionalproducing regions including Brazil, Canada andEurope, production is stagnating or falling.The star of the day is India, thanks to its buffalomeat production, which nearly doubled between2010 and 2013. India is forcing its way onto theworld market, where 25 percent of the beef is infact now buffalo meat from the subcontinent. Accordingto the US Department of Agriculture, Indiabecame the world’s biggest exporter of beef in2012 – just ahead of Brazil. Buffaloes are inexpensiveto keep. This makes their meat a dollar a kilocheaper than beef from cattle. In addition, theIndian government has invested heavily in abattoirs.Faced with the high price of feed, Braziliancattle-raisers are switching to growing soybeans.ProductionTradeTradeConsumptionWorld, forecast 2013,million tonnesFAOWorld, forecast 2013,million tonnesFAOWorld, forecast 2013,percentFAOWorld, per capita,forecast 2013, kg per yearFAO13.80.9 9.968.18.67.2114.2 308.2 30.2 10033.343.1106.413.390.179.3beef, vealpoultrypigs othersheep, goatsbeef, vealpoultrypigs othersheep, goatsdomestic consumptionexportdevelopeddevelopingworld10MEAT ATLAS

Worldwide meat production11.410.21.819.2USA1.22.80.1MexicoChile23.03.22.12.512.40.61.71.40.4 0.98.11.20.2Russia0.10.60.50.2Canada2.60.31.89.70.1Argentina3.313.1Brazil0.50.1Uruguay0.1EU0.30.2Algeria1.00.20.30.9 1.50.2South AfricaUkraine1.60.3 0.4Million tonnes, average 2010-2012,data for 2012 are estimated1.70.5TurkeyIran 2.9 2.90.80.50.30.90.7 0.1 Saudi ArabiaIndiaEgypt1.5 0.80.5Pakistan0.26.50.20.2Bangladeshbeef, vealpigspoultrysheep, goats50.417.1China4.11.50.2Malaysia0.31.00.7Korea1.30.51.70.70.5 0.1Indonesia2.11.00.30.6Australia0.61.4Japan0.50.2New ZealandFAOThis presents an opportunity – albeit a small one –for Indian buffalo-meat exporters.Africans are also starting to eat more meat,though both supply and demand are still notgrowing as fast as in other parts of the world. Productionhas risen in many countries in Africa, butsignificantly only in populous South Africa, Egypt,Nigeria, Morocco and Ethiopia. A typical Africaneats only 20 kilograms of meat a year – well belowthe world average. Imports of cheap poultry meathave increased, though often at the expense of localproducers.Whereas the developed world still dominates,growth now relies on the developing countries.Nevertheless, only one-tenth of the world’s meatis traded internationally. This is because meat canonly be exported if it meets and can documentthe quality requirements of the importing countries.Importers and consumers fear diseases suchas mad cow disease, foot-and-mouth disease andavian flu. The temporary interruption of the poultrymarket in Southeast Asia and the completecollapse of British beef exports have shown howinternational trade can dry up overnight.Small animals in big groups – poultry take offA stable outlook – only if speculation is limitedMeat production, trends and forecast, in million tonnes14012010080604020beef, vealpoultrypigssheep, goats01995 1999 2003 2007 2011 2015 20192021OECD/FAOReal meat prices, trends and forecast, in dollars per tonne5,0004,0003,0002,0001,000beef, vealpoultrypigssheep, goats01991 1996 2001 2006 2011 2016 2021OECD/FAOMEAT ATLAS11

CONCENTRATION: ECONOMIESOF SCALE BUT LESS DIVERSITYEconomic imperatives are the driving force behind the consolidation of theglobal meat industry. This may mean more efficient production, but it alsoconcentrates market power in the hands of just a few, much to the detrimentof smallholders. And it may be risky for consumers, too.Tight marginsexpose the businessto volatile marketprices and tradetensionsIn September 2013, Shuanghui InternationalHoldings Ltd. – the largest shareholder of China’sbiggest meat processor – completed a 7.1billion-dollar purchase of US-based SmithfieldFoods, Inc., the world’s biggest pork producer. Thesale exemplifies a new kind of consolidation that ishappening across borders. The direction of investmentis changing: it is now heading North fromthe global South. This reflects related shifts ineconomic growth, consumer demand, managementskills and corporate assertiveness over thelast two decades.JBS SA, a beef company based in Brazil, setthe stage in the late 2000s, when it acquiredmeat companies and poultry producers in theUnited States, Australia and Europe, as well asin Brazil. JBS is now the world’s biggest producerof beef. With its 2013 acquisition of Seara Brasil,a unit of rival company Marfrig Alimentos SA, itis also the world’s largest chicken producer. JBS isamong the world’s top ten international food andbeverage companies, with food sales amountingto 38.7 billion dollars in 2012.It also has business units in leather, pet products,collagen and biodiesel. Though JBS is not ahousehold name, its annual food revenues arehigher than those of major global food playerssuch as Unilever, Cargill and Danone. These figuresgive us an idea of what JBS’s size means on theground or at the slaughterhouse: its worldwidecapacities can slaughter 85,000 head of cattle,70,000 pigs, and 12 million birds. Every day. Themeat is distributed in 150 countries as soon as thecarcasses are “disassembled” , i.e. when the flesh isseparated from the bone.Because profit margins are tight in the meatbusiness, companies chase after economies ofscale. This means that they try to produce morewith greater efficiency and at a lower cost. For thisreason, the meat sector is concentrating in twosenses. Companies are getting bigger throughmergers and acquisitions – expanding across bordersand across species. And meat production isintensifying, so that more animals are housed togetherand are processed more quickly and withless waste. However, some market analysts pointout that the meat business is inherently risky andthat, based on recent financial performance, themulti-species strategy may be backfiring due todifferent cultures and processes that pose challengesto newcomers. In other words, knowinghow to grow, slaughter, process and transport cattlemay not translate easily into managing poultryoperations.Volatile feed-grain prices add to the financialrisk in the meat sector: higher-priced feed meanshigher production costs and lower profits. Withthe deregulation of commodity markets at theWorld meat prices comparedWorld food prices comparedIndices, 2002–4 = 100FAOIndices, 2002–4 = 100FAObeef, vealpoultrypigssheep, goatsFAO220220190190160130100160130100meatdairy productsfood70702007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2006 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 201312MEAT ATLAS

The Top Ten of the international meat industryCompanies by total food sales (2011–13), billion dollars7Smithfield Foods.3Founded in 1936; 2012 revenues:13.1 billion dollars. Largest porkCargill. Founded 1865,producer and processor in the USA.33 family-owned business. 2013Sold to Chinese Shuanghuirevenues: 32.5 billion dollars.International Holdings Ltd., with22 percent share in the US meatrevenue of 6.2 billion dollars,market, biggest single33in 2013exporter in Argentina,13 10 Danish Crown AmbAworldwide operationsVion9Cargill1355Smithfield Foods3Tyson Foods 78 Hormel Foods23910Vion. Founded in 2003after several mergers.2011 revenues: 13.2 billiondollars. Largest meat processorin Europe, rapid growth(2002: 1 billiondollars)9Danish Crown AmbA.Founded 1998 after severalmergers. 2012 revenues:10.3 billion dollars. Majorsubsidiaries in USA, Poland andSweden. Europe’s largest meatproducer, world’s biggestpork exporter13Nippon Meat PackersLeatherhead/ETC62TysonFood.Founded 1935; 2012 revenues:33.3 billion dollars. World’slargest meat producer andsecond-largest processor ofchicken, beefand pork10Hormel Foods.Founded 1891; 2012 revenues:8.2 billion dollars.40 manufacturing and distributionfacilities. Owner of “Spam”, aprecooked meat product;focusing on ethnic food15 JBSBRF13 14Marfrig84BRF. Founded in 2009 asBrasil Foods after a mergerof Sadia and Perdigão. 2012revenues: 14.9 billion dollars.60 plants in Brazil, presentin 110 countries1JBS. Founded in 1953;2012 revenues:38.7 billion dollars. World’s largestfood-processing company, leaderin slaughter capacity. Recentlyacquired Smithfield Foods’ beefbusiness and Malfrig’s poultryand pork units 8Marfrig. Foundedin 2000 after several mergers.2012 revenues: 12.8 billion dollars.Company units in 22 countries.World’s fourth largest beefproducer. In 2013, sold poultryand pork units to JBS6Nippon Meat Packers.Founded in 1949;2013 revenues: 12.8 billliondollars. Commonly known asNippon Ham. Operations in59 locations in 12 countries,mostly in Asia andAustraliaturn of the 21st century, feed prices have becomeless dependent on supply and demand, and moredependent on the speculative market manipulationsthat create price spikes. Add to that the rolebiofuels have had on prices for soy and maize, andthe volatility in the price of fertilizers. GoldmanSachs, an investment bank and titan of commoditytrading, was ever-present in the Shuanghui-Smithfielddeal. It had been hired to advise Smithfield onany potential sale, and it owns a 5 percent stake inShuanghui. In 2012, Goldman made an estimated1.25 billion dollars from commodity trading.Why does size matter? The implications of themeat industry’s two-tiered concentration – corporateconsolidation and the intensification of meatproduction – are wide-ranging. It is virtually impossiblefor the consolidated industry to coexistwith small producers. These multinational structuresboth wipe out a critical source of incomefor the global poor, and they radically diminishconsumer choices. Through economies of scale,concentration offers greater profit potential forstockholders and financiers; for other stakeholders,however, it increases risks to human health(including antibiotic resistance), food safety, animalwelfare, the environment, water security, laboursecurity and innovation.Extreme efficiency itself also carries a risk. Onecattle feedlot operator in the United States saysthat he is unsure where the economies of scaleend, because 100,000-head feedlots for cattle arenow possible. Several exist in the United Statesand their production costs are lower than forsmaller feedlots. Logistics in large productionunits are manageable nowadays, but the largerthe system, the more vulnerable it is. In an intensifiedenvironment, for example, pathogenscan spread more quickly and easily from oneanimal to another, both on the feedlot and duringtransport. The same is true for the slaughterhouseas the speed of processing increases. Furthermore,in the event of a disaster, such as a flood, the systemwill not be able to maintain its capacity. And ifconsumer demand declines, companies run witha low margin of safety may risk collapse. Therefore,insurance companies with custom-tailoredrisk assessments are becoming an important partof the modern meat business.Consumersmay get lowerprices, but therisks to societyare higherMEAT ATLAS13

animals slaughtered worldwideOfficial and estimated data, 2011, heads296000 00024 000 000buffaloescattlegoatssheeppigs1 383000 000430chickensducksturkeysgeese andguinea fowl000 000517000 00058654000 000110000 0002 817000 000Slaughter by countries, four most important, 2011, heads35 108 100USacattle andbuffaloes39 100 000Brazil46 193 000China21 490 0008 954 959 000USa11 080 000 000ChinaIndia5 370 102 000poultry 2 049 445 000BrazilIndonesia649000 000110 956 304USapigs59 735 680Germany661 702 976China44 270 000Vietnamsheep andgoats38 600 000Nigeria273 080 000China84 110 000India28 980 000BangladeshFAOSTATWestern Europe work in the slaughterhouses forshort periods, and are largely defenceless againstthe companies’ demands. Back in the 1960s, labourunions in the meat industry were still strong;in the last two decades they have had a muchharder time. Workers have little say in their workconditions, and collective wage agreements areunknown in most parts of the world.In most industrial countries, the slaughterhouseshave been relocated from the cities to therural periphery. The cruelty of slaughtering andimages of blood and squealing animals have tobe hidden from consumers’ eyes and ears. This reflectsa modern social norm: violence is banishedfrom public view. Slaughtering and butchery aremade invisible for the majority. The connectionbetween the meat and the living animal that istrucked to town and dies in the slaughterhousehas been severed. What most consumers now seeMEaT aTlaSis only a vacuum-packed meat product on a supermarketshelf.Finally, the treatment of animals in slaughterhousesis subject to criticism on two fronts. Theanimal welfare movement objects to frequentviolations of regulations and cruelty to animals,such as long transports, inadequate anaesthesia,or the beating of animals when they are drivenin the slaughterhouse.The animal rights movement, on the otherhand, criticizes the mass-slaughter of animalsas a matter of principle: it says that meat productionis always associated with violenceagainst animals. Animal rights activists do notwant to reform slaughter; they want to abolishit altogether. They say that the meat industry regardsanimals as mere products, whereas societyshould recognize their individuality and capacityfor suffering.we severedthe link betweenliving animals andthe packagedproducts15

BRIGHT PINK IN THE COLD CABINETIt’s goodbye to the neighbourhood butcher and hello to supermarketchains. The shift to Big Retail is now washing over developing countries.The demands of the rising middle classes are setting the agenda.“Food deserts”:where conveniencestores and fast-foodoutlets are the onlysource of foodRemember those butchers who cut up sidesof beef or pork in a tiled back room, andsold joints and sausages to customers over amarble counter in a room out front? In nearly allthe developed world, they have been consignedto history. Meat today, pre-cooled to 0–4°C, isdelivered to supermarkets from the wholesaleror direct from the abattoir. All the supermarketstaff have to do is put the goods in refrigerateddisplay cabinets, and customers can choose theready-packaged items themselves directly fromthe shelves. To keep self-service items lookingfresh for days on end, pork chops and chickenbreasts are vacuum-packed in an environmentthat is as kept as germ-free as possible. Thepackaging is then filled with an oxygen-rich gas.This gives beef and pork a red colour and suggestsfreshness – even though they may already havebeen in storage for several days.Meat, a luxury in many parts of the world only10 or 20 years ago, is now a part of the daily diet fora growing number of people in developing countries.Big supermarket chains such as Walmartfrom the USA, France’s Carrefour, the UK’s Tescoand Germany’s Metro are conquering the globe.Their expansion has sparked huge investmentsby domestic supermarket companies. The processhas been well researched. The first wave began inthe early 1990s in South America, in East Asian tigereconomies like South Korea and Taiwan, andSouth Africa. Between 1990 and 2005, the marketshare of supermarkets in these countries rosefrom 10, to 50 or 60 percent. The second wave, inthe mid-to-late 1990s, focused on Central Americaand Southeast Asia. By 2005, supermarkets accountedfor 30–50 percent of the market sharethere. The third wave began in 2000 and washedover China and India, as well as big latecomerssuch as Vietnam. In only a few years, supermarketsales in these countries were growing by 30 to 50percent a year.Why this huge shift? It is not only due to therising purchasing power of the middle classes,but also to more fundamental changes in society.In Pakistan, for example, cities are expanding soquickly that traditional methods of supplyingmeat and dairy products cannot keep up with thedemand. The city of Lahore is growing by 300,000people a year. The result is product shortages andpoor quality, factors that drive the middle classesinto the supermarkets, says the Express Tribune,a Pakistani daily. Working women, who are stillresponsible for cooking for their families, have notime to go from shop to shop to check the meatquality or haggle over prices.Investing in spacious stores is worthwhile inplaces with thousands of potential customers. Inlocations where mobility is high, such as the carfriendlysuburbs of US cities, poor people cannotfind a grocery store within walking distance thatsells fresh produce they can prepare themselves.The only food they can buy is ready-to-eat mealsSlowing down in ChinaExpansion mode in IndiaAnnual percentage change in store growth, 2010–14, and market shares, 2012, percent121110987654321independentchain02010 2011 2012 2013 2014(estimate)84.1Yum!*McDonald’sTing Hsinother fast-food chainsindependent fast food6.52.31.54.3Hua Lai ShiShigemitsuKungfuEuromonitor0.60.40.3Food retail chains, stores and planned additionsexisting, 2012/13planned, 2013/14+ 125602*Kentucky Fried Chicken, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell+38–50166+ 250500Domino’s McDonald’s Yum!*Business Standard16MEAT ATLAS

from fast-food outlets. Researchers call these areas“food deserts”. At the same time, the contents ofshoppers’ trolleys come from further and furtheraway. Products come from central warehousesand big abattoirs that supply all the retail branchesin a region or even a whole country. The huge volumesand secure cold chains ensure that the itemsare usually fresh, despite long transport distances.Selling standardized products simplifies advertisingand gives the supermarket chains enormousmarket power, enabling them to dictateprices to their suppliers. At the same time, the supermarketchains compete with each other. Thispushes prices down, and means that locally producedproducts are relegated to particular niches.With the opening of global markets, millions ofsmall-scale retailers have gone under becausethey do not handle the volumes needed to justifysuitable cold rooms or to ensure the continuouscooling of meat, eggs and milk.Price wars and price dumping result in periodicscandals involving meat that is sold past itssell-by date, produced using hormones, or mislabelled.Global supply chains are particularly complexfor processed products. They have resultedin donkey, water buffalo and goat meat endingup on plates instead of beef in South Africa, andhorsemeat being sold as beef in Europe. In India,meat labelled as buffalo in fact came from the illegalslaughter of cattle.In China, the world’s biggest producer andconsumer of meat, pork is the most popular typeof meat. Most pigs are still raised by smallholdersrather than in intensive factory farms, althoughthis is changing and the government is pushinghard for intensive pig-raising. Big abattoirs arestill rare. Most slaughterhouses continue to usemanual or semi-mechanical methods, and hygieneconditions are seldom checked. Many placeslack a functioning cold chain, so most meat is soldto consumers already cooked. But the demand formeat from supermarkets is growing, and it nowaccounts for 10 percent of total meat sales. Suchproducts are seen as “Western” and are growingin popularity because they are cheap and associatedwith freshness, hygiene and comfort.International fast food chains like McDonald’sand Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) open newbranches in China every day: McDonald’s currentlyhas around 1,700 restaurants, and KFC, themarket leader, has announced its 4,500th outlet.Customers are familiar with pledges made bythese chains, ensuring that their suppliers are constantlycertified and monitored. However, eaters’appetites have repeatedly been spoiled by foodscandals. In late 2012 and early 2013, KFC had tograpple with two separate cases of poultry meatcontaminated by antibiotics. Its business fell by10 percent and had still not yet recovered by theautumn of 2013. McDonald’s was pulled into themire: its sales also declined. Retailers must fearconsumers – even in China.Growth in the supermarket fridgesRetail value, 2012/13, million dollars, by countryUSCAMXUSUSARAR ArgentinaAU AustraliaBR BrazilCA CanadaCN China600 +300–599VEBRUKRUUK DE UAFRTRIRNGSAdrinking milk productsUKFRDEDETRready meals (with/without meat)DE GermanyDZ AlgeriaFR FranceID IndonesiaIN India150–2990.1–149RUIRCNchilled processed meatCNcanned/preserved meat productsUSUSMXUScheeseARVEARIR IranMX MexicoNG NigeriaRU RussiaSA Saudi Arabiano growthnegative growthBRBRFRUKDEZAFRDZTRNGIRIRfrozen processed poultryTR TurkeyUA UkraineUK United KingdomINIRRURUCNRUCNIDAUUS USAVE VenezuelaZA South AfricaEuromonitorMEAT ATLAS17

FREE TRadE VERSUS SaFE FoodThe Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement currently beingnegotiated between the United States and the European Union promises to boosttrade and jobs. But it may also weaken existing consumer-protection laws on bothsides of the Atlantic.officials discusslower barriers forpharmaceuticalsbehindclosed doorsIn theory, liberalizing trade should increase economicactivity and lift all boats, creating jobsand economic growth for all. But reality can bequite different. Free-trade deals are no longer onlyabout quotas and tariffs. They can have a sizeableimpact on the ability of governments to set standardsfor meat production and to regulate theglobal meat industry – from animal welfare,health, labelling and environmental protectionto the industry’s corporate legal rights.But approaches to food safety often differfrom country to country. The European Unionbases its safety rules for food and chemicals onthe “precautionary principle”. This cornerstoneof Union law permits the EU to provisionally restrictimports that might carry a human or environmentalrisk where the science is not definitive.The United States states that it makes decisionsbased on “sound science” and cost-benefit analysis,which in the case of GMOs has been based onindustry supplied data.Despite their different food-safety regimesand consumer preferences, the European Unionand the United States started negotiations for aTransatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership(TTIP) in 2013. Intended to bolster their fragileeconomies, this could become the biggest bilateralfree-trade agreement in history. The UnitedStates is the EU’s biggest market for agriculturalexports, and the EU is the United States’ fifth-largesttrading partner for agricultural goods. Powerfulinterest groups on both sides of the Atlantic,including the farm, feed and chemicals industries,are pushing hard for an agreement that dismantlesbarriers to trade in agriculture, includingthe meat subsector.Such an agreement could result in drasticchanges in standards on the use of antibiotics inmeat production, genetically modified organisms,animal welfare, and other issues. “Regulatorycoherence” to expand trade between the UnitedStates and the EU sounds good in principle. Butthe issues are complex. Consumers on both sidesof the Atlantic should be concerned that the TTIPcould derail attempts to strengthen food safetyand animal welfare in the meat industry. Industryon both sides of the Atlantic will seek to lock in thelowest standards in order to expand its markets.winners and losers from transatlantic trade talksPercentage expected gains and losses in real per capita income as a result of tougher competition in core markets.Assumes that tariffs and non-tariff barriers are abolished, and other trade regimes remain unchanged.IFO13.4USaCanada-9.56.9Ireland9.7UK7.3Sweden 6.2Finland6.6SpainMexico-7.2-9.5–-6.1-6.0–-3.1-3.0–0.00.1–3.03.1–6.06.1–13.4no dataaustralia-7.418MEaT aTlaS

The United States has for years tried to repulseEU restrictions on genetically modified organismsand the use of controversial food and feedadditives. There is the case of ractopamine, usedin the United States as a feed additive to increaselean meat production in pork and beef. Its use isbanned in 160 countries, including the EuropeanUnion, largely because of the lack of independentscientific studies assessing its safety for humanhealth. Currently the United States is not allowedto export meat from animals treated with ractopamineto the EU. American agribusiness and meatprocessingcompanies want the EU to lift this banand include the issue in the TTIP negotiations.After several years of relative quiet, an oldtrade dispute has been reopened. Under the TTIP,the USA is once again seeking approval of peroxyacid,a substance with antimicrobial propertiescommonly used in the USA to clean raw poultryafter slaughter. In the EU, using peroxyacid is seenas contrary to the “farm to fork” concept of minimizingthe use of chemicals, allowing only hotwater for decontaminating poultry.Also, the TTIP presents an opportunity formultinational corporations to bypass Europeancitizens’ opposition to genetically modified foods,many of which are prohibited in the EU. The USgovernment and food companies have challengedthese rules as unfair “technical barriers” totrade. Now, through closed and non-transparentnegotiations, the fear is that the EU will use theTTIP negotiations as a reason to lower standardson the use of genetically modified organisms.The EU, for its part, is seeking to overturn theUS ban on beef imports from the EU. The UnitedStates prohibits the use or import of feed ingredientsthat are known to transmit bovine spongiformencephalopathy (BSE, or “mad cow disease”).Food-safety advocates in the USA are concernedthat EU policies governing the use of feed additivesmade from ruminants are not strongenough to prevent contamination. Since the EUis currently considering relaxing the standardsthat regulate the use of feed additives made fromruminants, the risk of trade in beef contaminatedwith BSE would increase.Moreover, food-safety measures that seek toeliminate health and environmental impacts ofthe meat industry could be challenged underthe “investor-state dispute settlement” mechanism.This clause present in many trade agreementsallows companies to sue governments forcompensation over rules that affect their profits.Agribusiness firms are lobbying to make foodsafetystandards “fully enforceable” through theinvestor-state mechanism in the TTIP. Since thismechanism gives international investors the legalright to “stable investment conditions”, makingchanges in environmental or animal health lawwould be much more difficult.The TTIP could also make it much more difficultto address the negative environmental, socialMeat trade between the USA and the EUImports and exports, million dollarstotal meat tradeUSAbeef, vealpoultry, eggsand health aspects of industrial animal production.Instead of driving standards to the bottom,consumers and activists in the United States andthe EU should demand that governments use theopportunity of the TTIP to raise standards andrigorously regulate the meat industry. Or theyshould abandon the talks altogether.Feed trade between the USA and the EUImports and exports, million dollars2010 2011 2012corn (maize)sorghumfeed andfodderUSAoil seedssoy2010 2011 2012946 1,154 9881,652 2,031 2,154136 231 223298 326 355219 218 199741 868 84543 239 1838 239 1320 492 2652,072 1,632 2,6761,108 795 1,481217 270 265872 928 1,016847 897 976EUporkcheeseEUfeed andfodderoil seedsolive oilUSDA ERSUSDA ERSMEAT ATLAS19

THE HIDDEN COSTS OF STEAKThe price tag on a package of meat does not reflect the true cost of producing thecontents: the hidden costs to the environment and the taxpayer are much higher.If these costs are included, livestock raising would probably make a net loss.Damageto nature ishard to measurein monetarytermsAround 1.3 billion people worldwide livefrom animal husbandry – most of them indeveloping countries. The majority grazetheir animals on land around the village, somemove from place to place with their herds, andothers keep a few chickens, cattle or pigs neartheir homes. In the developed world and rapidlygrowing economies, the number of livestockkeepers is falling. The livestock sector is becomingindustrialized and meat producing companiesare expanding.The profits of these companies are notjust a result of their own efforts. They are alsobuilt on the environmental damage caused byfactory farming and the use of livestock feed –costs that the companies do not have to pay. Inaddition, they receive subsidies from the state.These subsidies are often distributed true to themotto: the bigger the company, the higher thesubsidy. No consolidated economic and ecologicalaccounting has yet been done, but we can discernits broad outlines. When an animal productis purchased, three prices have to be paid: one bythe consumer, one by the taxpayer and one bynature. The consumer uses the first price to judgethe item’s value. The other two prices representhidden subsidies to the people who produce andmerchandise it.The costs borne by the environment are probablythe biggest, but they are hard to calculate.Over the last three decades, economists and accountantshave developed their own “environmental-economicaccounting” that estimatesdamage to nature in monetary terms. It covers thecosts of factory farming that do not appear on thecompany’s balance sheet, such as money saved bykeeping the animals in appalling conditions. Coststo nature are incurred by over-fertilization causedby spreading manure and slurry on the land andapplying fertilizers to grow fodder maize and othercrops. If the quality of water in a well declinesbecause of high nitrate content, the costs arehard to calculate: they often are only recognizedwhen the well has to be capped and drinking watershipped in from somewhere else. Other externalities– costs that do not appear in the consumerprice – arise if over-fertilization means the soil canno longer function as a filter for rainwater, if erosioncarries it away, if biodiversity declines, or ifalgal blooms kill fish and deter tourists.However, for the majority, the most extensivedamage occurs further away from the cause. Intensivelivestock production releases nitrogencompounds such as ammonia into the atmosphere,contributing markedly to climate change.According to the European Nitrogen Assessmentin 2011, this damage amounted to some 70 to 320billion euros in Europe. The authors of this studyconcluded that this sum could exceed all the profitsmade in the continent’s agricultural sector.If this were counted, the sector as a whole wouldmake a loss.Different regions, different levels of supportPercentage of gross farmreceipts from governmentfor livestock, by region,classification by OECD,2010–1224.3OECD4.8Europe12.5Commonwealth ofIndependent StatesNorth America14.4Asia2.61Southern hemisphere20MEAT ATLAS

direct subsidies for animal products and feedIndustrialized countries (OECD members), estimates for 2012, in billion dollarsOECD1.5eggs18.0beef and veal7.3pigmeat2.3soybeanspoultrymilk15.36.51.1sheepIn China, the immediate costs of over-fertilizationare estimated at 4.5 billion dollars a year,mainly because water quality suffers from intensivelivestock production. The main problemis that in rapidly developing areas of East Asia,farmers and agricultural firms are replacing thetraditional organic fertilizers – manure and faeces– with synthetic nitrogen. Manure, which usedto be considered the best type of fertilizer in integratedfarming, now has to be disposed of somehow– in a river, on a dump, or trucked to where itcan be used. To ensure the highest yields, the fieldsare fertilized with commercial agrochemicalscontaining readily soluble nutrients as well. Thisresults in a double burden on the environment.Cheap meat is made possible only by polluting theenvironment.The other big unknown in the real price ofmeat are subsidies using public funds. A packageof subsidies may consist of many different components.The European Union offers subsidies forfodder crops and supports up to 40 percent of thecost of investing in new animal housing. A crisisfund, set up in 2013, can be used to support factoryfarms, for example to support the export of meatand milk powder.Further burdens are heaped onto nationaltaxpayers. They pay for the costs of transport infrastructure,such as ports needed to handle thefeed trade. In many countries, meat is subject to areduced level of value added tax. In addition, lowwages in abattoirs make it possible to producemeat cheaply. From a political point of view, lowwages can be seen as subsidies because companiesMEaT aTlaScan pay so little only if the state does not impose astatutory minimum wage.Few poor countries can subsidize their farmersin this way. Instead, they tend to support themthrough laws that permit the exploitation ofpeople and the environment. To remain thecheapest suppliers of feed or meat in the worldmarket, governments allow workers to toilin slave-like conditions and for little pay, theylease government land to large-scale producersat cheap rates, and they fail to act against loggerswho clear areas of land for ranchers to occupy.Farmers’ income from public moneyIndustrialized countries (OECD members), percentage of gross farm receipts,by animal product504030201001995–972010–12beef, veal pigs poultry sheep milkPoor countriessupport theindustry throughweak laws andlax controlseggsOECD21

WHY FARMS KILL FISH: BIODIVERSITYLOSS ON LAND AND IN WATEROverfertilization harms plants and animals and damages ecosystems worldwide.Nitrates in groundwater can cause cancer. In coastal waters, they can result inoxygen-starved “dead zones”.Agriculture’s share of total environmental impact22Industrial countries (OECD members), 2007–9, in percent35Put lots of nitrogen in a body of water and itsoxygen content goes down. How serious aproblem that is can be seen in the coastalwaters of the Gulf of Mexico. Around the mouthsof the Mississippi, some 20,000 square kilometresarea used water used energy used pesticide purchasesammoniaemissionsWater pollution:90 7545emissions ofozone-damagingmethylbromidenitrates insurface waterphosphorus insurface water70nitrogenoxide280* 70*70*nitrates ingroundwater8greenhouse gasemissions50*phosphorus ingroundwater40methane701carbondioxide30*nitrates incoastal waters* maximum valueOECDof the sea have so little oxygen that a “dead zone”has formed, in which shrimp and fish cannot survive.In 2011, researchers found that sperms weregrowing in the sex cells of female fish in the Gulfbecause a lack of oxygen was interfering withtheir enzyme balance.The cause of this marine desolation lies in theover-fertilization of the Mississippi basin, wherealmost all the United States’ feed production andindustrial farms are concentrated. Nitrogen andphosphorus are washed down the river into theGulf. There these nutrients stimulate the growthof algae, aquatic plants and bacteria, which useup the oxygen dissolved in the seawater. A litre ofseawater commonly holds around 7 milligrams ofdissolved oxygen; around the mouths of the Mississippiit holds less than 2 milligrams. The only organismsactive here are those that do not dependon oxygen to live.The US marine biologist Peter Thomas says thataround 250,000 square kilometres of coastal watersworldwide suffer from severe seasonal oxygendeficiency. In Asia, pig and poultry farms in coastalChina, Vietnam and Thailand pollute the SouthChina Sea with nitrogen. The northern part of theCaspian Sea is loaded with nitrogen that comesdown the Volga. Many of the seas surroundingEurope are affected: the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea,the Irish Sea, the Spanish coast and the Adriaticall have dead zones. The problems are caused notonly by nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, butalso by potassium, drug residues, disease-causingorganisms and heavy metals.It is not just the seas: industrialized livestockproduction harms the land too. Slurry and manurefrom livestock-producing areas are applied,often indiscriminately, to the soil. They can posean even greater threat than the overuse of mineralfertilizer, especially on well-drained soils. Nitratesare washed down into the groundwater, whichcan lead to contamination of our drinking waterand damage our health. In our bodies they can beconverted into nitrosamines, which are suspectedto cause cancer of the oesophagus and stomach.Over-fertilization threatens the habitat of nearlyall the endangered species on the Red List compiledby the International Union for Conservationof Nature. Excessive use of chemical fertilizers,pesticides and herbicides harms organisms in thesoil and water, and damages ecosystems.MEAT ATLAS

Tropical rainforests are especially rich in biodiversity,but more than one-fifth of the Amazonrainforest has already been destroyed. Livestock isone of the major causes: trees are cleared to createpastures or grow soy to feed animals. And many ofthe pastures are turned into soy fields after a fewyears. The widespread conversion of pasture tocropland to produce feed in South America andEurope cuts biodiversity, since grassland usuallycontains more species and offers a better habitatfor insects and other small animals. But intensivegrazing often leads to a loss of native species, asfarmers sow new types of grass that are more valuableas feed. This marginalizes other species. Fencingto convert an open range into ranches can cutthe migration routes of wild animals, keep themaway from waterholes, and trigger local overgrazingby cattle.Mixed farms, where crops and animals aremanaged on the same farm, often have variouspatches of vegetation – hedges, woodlots and gardens– which support a range of insects and smallanimals as well as certain wild plants. In Europe,the USA, South America and East and SoutheastAsia, many such mixed farms are being rapidlyreplaced by “landless” systems to raise pigs andpoultry on an industrial scale. In such systems, theanimals are fed with crops purchased from otherfarms and often from abroad. This is one of themain reasons for the nutrient imbalances in freshwater,soils and the ocean.In industrial systems, the genetic diversity ofthe livestock itself is usually very narrow becauseFodder fields and the dead zone in the Gulf of MexicoMississippi River drainage basin, land use and water pollutioncropped landdedicated to feedless than 5 percentless than 20 percent20–50 percentmore than 50 percenthypoxic zone due to nitrogen and phosphate loadsfarmers all over the world are offered the samefew breeding lines. Animals are no longer adaptedto their diverse natural environments. Instead,they are bred to suit the uniform conditions oflivestock houses, where the temperature, moistureand light are carefully controlled and feedcomes from the global market. In other words,biodiversity is at its lowest in a livestock pen onan industrial farm.FAOThe oversizedfootprint of factoryfarms: growingfeed and spreadingslurryNitrogen on land and in the aquatic systemMain sources of nitrogen, 2005livestockfertilizersENAMEAT ATLAS23

A SPECIES-POOR PLANETThe genetic basis of livestock is getting ever narrower. We are relying on a few,specialized breeds of animals, such as the black-and-white Holstein-Friesiandairy cattle that are raised in over 130 countries. A few high-yielding strains alsodominate the production of chickens, goats, pigs and sheep.24One breedingcock can sire upto 28 milliongenetically similaroffspringTwo winners of globalizationPresence of Holstein-Friesian dairy cattlePresence of Large White pigHumankind has domesticated 30 species oflivestock, and in doing so has created anincredible range of breeds: around 8,000have so far been documented by the Food andAgriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO). Many of these breeds are kept by smallscalelivestock keepers – the majority of whomare women – who produce most of the world’smeat while conserving the world’s livestockdiversity. For many poor households, animals,especially chickens, sheep and goats, are animportant source of livelihood. They choose indigenous,multipurpose breeds because they areadapted to local, often harsh conditions.Eight types of livestock are used in heavy industrialproduction: cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens,turkeys, ducks and rabbits. Of these, a fewbreeds have been developed further. The industryhas developed these into a few high-yieldingbreeding lines, which are crossbred to produce theanimals that we eat. Such hybrid breeding is usedespecially in poultry and pigs, further restrictingthe genetic diversity in these animals.FAOThe 1950s marked the advent of the wide-scalecommercial production of meat and a concomitantloss of genetic diversity. Corporate breedersfocused on maximizing production and commerciallyuseful traits such as rapid growth, efficientfeed conversion and high yields. The result is highperformanceand genetically uniform breeds thatrequire high-protein feeds, costly pharmaceuticalsand climate-controlled housing to survive.Now, a small number of transnational firmssupply commercial breeds for an ever-increasingshare of the world’s meat markets. The companiesalso dominate research and development in thehighly-concentrated animal genetics industry,particularly for poultry, swine and cattle.One third of the world’s pig supply, 85 percent ofthe traded eggs and two-thirds of the milk productioncome from these breeds.In the poultry sector, four firms account for 97percent of poultry research and development. Inbroilers, three companies control a 95 percentmarket share. Two companies control an estimated94 percent of the breeding stock of commerciallayers. Two companies supply virtuallyall of the commercial turkey genetics.The top four companies account for two-thirdsof the total industry research and developmentof both swine and cattle.While aquaculture currently accounts for asmall slice of the industry, it is the fastest growingsector. Many of the top animal genetics firmshave recently taken the plunge into aquaculture.They work with only a handful of species,primarily Atlantic salmon, rainbow trout, tropicalshrimp and tilapia.Most of the global suppliers of livestock geneticsare privately held and do not publish figureson revenues or investments, nor do they providean inventory of their proprietary germplasm orbreeding stock collections. This means that thereis not much information being made publiclyavailable about the size of private-sector animalgenetics markets, and the sales and prices of geneticmaterials. But it is clear that the market forcommercial animal genetics is tiny compared tothe commercial seed market, its crop counterpart.China is now the world’s largest consumer ofmeat, with pork being the country’s most popularprotein, and demand is rocketing. The vastmajority of China’s pork supply still comes from“backyard” pig producers, but Chinese policiesfavouring vertical integration, where one firmMEAT ATLAS

Animal genetics industry: the Big Seven global breedersCompanies and profiles7Tyson Foods.Sold 33 billion dollars worth ofbroilers in 2012. SubsidiaryCobb-Vantress distributesbroiler breeding stock tomore than 90countriesSmithfield FoodsTyson Foods76Smithfields Foods.World’s largest pork processorand pig producer. Turnover 13 billiondollars (2012); in 2013 acquiredby Shuanghui, China’s largest meatprocessor, for 7.1 billion dollars,including the company’s pigbreeding subsidiary6Genus3Groupe Grimaud3Genus. Sells pigs,dairy and beef cattle.Revenues of 550 million dollarsin 2012. Operates in 30 countries,sells to another 40.2,100 employees(2012)45Hendrix Genetics2EW Group4Groupe Grimaud.Sells broilers, layers, pigs;aquaculture. Privately held;turnover 330 million dollars(2011), of which 75 percentis internationaltrade2EW Group. The world’slargest player in industrial poultrygenetics. Sells broilers, layers,turkeys; aquaculture. Formerly theErich Wesjohann Group.Privately held, norevenues published; 5,600employees (2011)5Hendrix Genetics.Sells layers, turkeys, pigs;aquaculture. Privately held,2,400 employees (2012). Jointdevelopment agreement withTyson Foods’ Cobb-Vantresssubsidiary1Charoen Pokphand Group1Charoen Pokphand Group.Sells broilers and pigs;aquaculture. Agro-industrial andtelecoms giant with annualrevenues of 33 billion dollars, with feed,farm and food revenues of 11.3 billiondollars (2013), including animalbreeding operationsand pork unitsETC GROUP/USDAmanages several stages in the production process,mean that by 2015, half the country’s pigswill come from factory farms. Although China ishome to more pig diversity than any other country,Chinese factory farms rely on imported breedingstock. Numerous swine genetics firms haverecently announced deals with China. This trendis likely to accelerate as a result of the 2013 purchaseof Smithfield Foods, for 7.1 billion dollars, byChina’s largest meat processor, Shuanghui International.Smithfield Premium Genetics, the company’spig breeding subsidiary, is part of the deal.As industrial-scale livestock production replacesChina’s small-scale pig producers and chickenfarmers, Chinese factory farms, like those in theUnited States, increasingly rely on high levels ofantibiotics in feed to promote faster growth and tohelp livestock survive crowded conditions.The tightly-held ownership and control ofbreeding stock for industrial, large-scale animalproduction contrasts sharply with, and threatensthe survival of, millions of smallholder farmers,fishers and pastoralists. In a world facing climatechange, breeds that are resistant to drought, extremeheat or tropical diseases are of major potentialimportance as sources of unique genetic materialfor breeding programs. In 2007, 109 countriessigned the Interlaken Declaration on AnimalGenetic Resources. This declaration affirms theircommitment to ensure that the world’s animalbiodiversity is used to promote global food security,and remains available to future generations.It also notes that “continuing erosion and loss ofanimal genetic resources for food and agriculturewill compromise efforts to achieve food security,MEAT ATLASimprove human nutritional status and enhancerural development.”According to FAO’s 2012 update on the state oflivestock biodiversity, almost one-quarter of the8,000 unique farm animal breeds are at risk of extinction,primarily due to the growth of the industriallivestock sector. The narrow genetic diversityof commercial animal breeds increases their vulnerabilityto pests and diseases. It also poses longtermrisks for food security because it shuts outoptions to respond to future environmental challenges,market conditions and societal needs, allof which are unpredictable. In the face of climatechange, the long-term sustainability of livestockkeepingcommunities, as well as industrial livestocksystems, is jeopardized by the loss of animalgenetic diversity.Dominating the livestock industryMarket share of breeds for milk, beef and pork production in the United States, in percentHolsteins8360Angus,Hereford,Simmental75from threevarietiesMEDILL25

ANTIBIOTICS: BREEDING SUPERBUGSIndustrial producers use large amounts of pharmaceuticals to prevent diseases fromspreading like wildfire among animals on huge factory farms, and to promote fastergrowth. But this is dangerous: bacteria are developing resistance to drugs that arevital to treat diseases in humans.Much strictercontrols worldwideare needed tostop the abuse ofmedicinesCause of death: scratched knee. What soundslike fiction could soon be reality. The WorldHealth Organization (WHO) warns that ifwe continue our reckless use and abuse of antibioticsin animal husbandry, we could enter a postantibioticera in which health conditions thatare now easily curable will again become lethal.In spite of this, few countries have addressed theuse of antibiotics in livestock raising. Antibioticsare used to ensure that the animals endure theconditions in factory farms until slaughter. Alarge part, however, is also used to increase andspeed growth. Pigs that are given antibiotics,for example, need 10 to 15 percent less feed toreach their market weight.Although the European Union prohibitedantibiotics to promote growth in 2006, this didnot lead to a significant decrease in their use onfarms. Systematic inquiries have recently revealedthat 8,500 tonnes of antimicrobial ingredientswere distributed in 25 European countries in2011. Germany has the highest (overall) consumptionat 1,600 tonnes a year. However Denmark,where veterinarians are subject to relatively tightcontrols, reports only a third of the German peranimal head level.In other parts of the world, the use of thesevaluable drugs is subject to hardly any regulationsor restrictions whatsoever. In China, it is estimatedthat more than 100,000 tonnes of antibiotics arefed to livestock every year – mostly unmonitored.In the United States, livestock production consumed13,000 tonnes of antibiotics in 2009, andaccounts for nearly 80 percent of all the antibioticsused in the country. With resistant bacteria andfood-borne illnesses on the rise, the US Food andDrug Administration recently recommended restrictingthe application of antibiotics in livestockproduction “to those uses that are considered necessaryfor assuring animal health”. It is doubtfulwhether these gently worded, voluntary guidelinescan limit the overuse – and the demise – ofantibiotics in the future.Industrial farming has intensified at a rapidpace during the past decades and antibiotics havebeen one of the main driving forces behind thisprocess. They perform two functions: they helpanimals survive the dismal conditions of livestockproduction until slaughter, and they make theanimals grow faster. According to WHO, moreantibiotics are now being fed to healthy animalsrather than to sick human beings. The use of antibioticsas growth promoters is legal in large partsof the world, and until recently, nearly all largescalemeat production in developed countries involvedthe continuous, low-dose administrationof antibiotics in animal feed.Livestock are usually given the same antibioticsas humans. Every time an antibiotic is administered,there is a chance that bacteria developresistance to it. “Superbugs” – pathogens suchas Escherichia coli, salmonella or campylobacterthat can infect humans as well – are resistantto several different antibiotics, and are thereforeparticularly difficult to treat. The imprudent useof antibiotics in livestock production exacerbatesHow far we are – distribution of antibiotics and resistant bacteria in the USASales of antibiotics, million pounds/kilogramslbs kilograms29.9 13.6Antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus faecalis detected insupermarkets, 2011, percent of all samplesEWG2010for meat and poultry productionto treat ill people81turkey69pork107.703.52001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 201155beef39chicken26MEAT ATLAS

European sales of antimicrobial agents for food-producing animalsSales in milligrams per kilogram of meat stockbiomass, 2011, including horsesantibiotics are used systematicallyto combat diseases infactory farmsresistant bacteria can enterthe human body when peopleeat meatbacteria “defend” themselvesby mutating, thus becomeresistant to the antibioticsantibiotics used totreat humans areineffective against theresistant bacteria161Portugal6Iceland4Norway51United Kingdom114 4349DenmarkNetherlandsIreland175 211249Spain24Finland83Belgium GermanyCzech Rep. 4479* 54 Slovakia117 SwitzerlandAustria 43Slovenia 192France104HungaryBulgaria370Italy14Sweden6635 EstoniaLatvia120 42LithuaniaPoland408EMA* Swiss sales unauditedCyprusthe resistance problem. They are usually administeredto whole herds of animals in the feed orwater. It is impossible to ensure that every singleanimal receives a sufficient dose of the drug. Diagnostictests are rarely used to check whether theright kind of antibiotic is being used.Resistant bacteria can pass from animals tohumans in many ways. An obvious link is the foodchain. When the animals are slaughtered andprocessed in an abattoir, the bacteria can colonizethe meat and be carried into consumers’ kitchens.But that is not the only way that humans can beexposed to such superbugs. Resistant bacteria canbe blown several hundred metres by exhaust fansof livestock houses. The bacteria are abundantin manure, which is spread on fields as fertilizer.Once in the soil, the bacteria can be washed intorivers and lakes. Bacteria interact both on farmsand in the environment. They develop furtherand reproduce, exchanging genetic information.In doing so, they enlarge the pool of bacteria thatis resistant to once-powerful antibiotics.The production of animals and meat isglobally connected with trade and transportlinks spanning the globe. These links enableresistant bacteria to spread rapidly. Superbugsare, in the words of the WHO, “notoriousglobe-trotters”. The imprudent use of antibioticsin one part of the world thus poses a threatnot only to the local human population, but endangersthe health of people in other parts of theworld as well.Factory farmsare inevitablybreeding dangerousnew strains ofbacteriaHow far we are – antibiotic resistance by pathogen and type of meat in GermanyPercentage of samples. Many pathogens in these groups of bacteria can in humans lead to serious diarrhoea and even death10080SalmonellaEscherichia coli6040Campylobacter jejuniBVLNumber ofclasses of antibioticsto whichpathogens areresistent :4 or more321200turkey meat(retailer)turkey(abattoir)turkey(farm)broiler chicken(farm)turkey meat(retailer)turkey(abattoir)turkey meat(retailer)turkey(abattoir)fattenedcalf (farm)broiler chicken(farm)Pathogens notyet resistent:susceptibleMEAT ATLAS27

WHEN THE TANK IS RUNNING DRYThe growth of the world’s livestock industry will worsen the overuse of rivers andlakes. It’s not that animals are particularly thirsty; but a lot of water is needed togrow the fodder they eat, and dung from factory farms pollutes the groundwaterwith nitrates and antibiotic residues.2.5 billionpeople alreadylive in areassubject to waterstressConsumption of the world’s most importantform of sustenance – fresh water – has increasedeightfold over the past century. Itcontinues to increase at more than double therate of human population growth. As a result,one-third of humanity does not have enoughwater, and 1.1 billion people have no access toclean drinking water. Lakes, rivers, and oceansare pumped full of nutrients and pollutants.At the same time, the water table is droppingdramatically in many parts of the world. Bigrivers, such as the Colorado in the United Statesand the Yellow River in China, no longer reachthe sea for months because so much of their waterhas been extracted. Water consumption continuesto rise as the world population grows. Withouta limit to consumption, the supply of watermay collapse.The biggest water user, and the main cause ofthe global water crisis, is agriculture. It consumes70 percent of the world’s available freshwater,while households (10 percent) and industry (20percent) make do with a lot less. One-third of agriculture’sshare goes into raising livestock. This isnot because cows, pigs and chickens are especiallythirsty, it is because they consume water indirectly,as feed.It takes 15,500 litres (15.5 cubic metres) of waterto produce just one kilogram of beef, accordingto a WWF study. A small swimming pool full of waterfor four steaks? A surprising amount, until welook at what a cow eats during its lifetime: 1,300kilograms of grain and 7,200 kilograms of forage.It takes a lot of water to grow all this fodder. Addto that 24 cubic metres of drinking water and 7 cubicmetres for stall cleaning per animal. The bottomline is that to produce one kilogram of beef,one needs 6.5 kilograms of grain, 36 kilograms ofroughage, and 15,500 liters of water.Statistics from the Food and Agriculture Organizationof the United Nations are just as impressive.Producing 1,000 calories of food in theform of cereals takes about half a cubic metre ofwater. Producing the same number of calories asmeat takes four cubic metres; for dairy products,6 cubic metres. And these are average figures. Rememberthough, that not all cows are equal: anintensively raised cow uses a lot more water thanone that is put outside to graze. And around theworld, more and more animals are being kept indoorsrather than outside.The effect of livestock on water is not limited toconsumption. Water pollution caused by nitratesand phosphorus from manure and fertilizers area big problem for the livestock industry. In manyareas, over-fertilization is a bigger problem thana lack of fertilizer. Plants cannot absorb the nutrientsthat percolate down into the soil, and endup in groundwater as well as in rivers and lakes.Nitrates in groundwater often end up in wellsand springs. If the authorities check nitrate levels,people can avoid drinking it, but such checks doMoisture extraction for food, fodder and fibre productionHoekstra/MekonnenMillimetres per year0–1010–100100–500> 50028MEAT ATLAS

Water used for meat production in G20 countries2,0001,5001,0005000Most important developed and developing countries,cubic metres used per person per yearSouth Koreanot take place in many areas. Further problemsinclude contamination by antibiotics from thelarge amounts of drugs used in factory farms, andthe lowering of the water table in much of Asia becauseof pumping from wells. Dry wells have to bedeepened, and they may tap into rocks that havea high content of fluoride and arsenic; substancesthat can harm both people and animals.If meat consumption continues to rise rapidly,the amount of water needed to grow animal feedwill double by the middle of this century, accordingto the Worldwatch Institute. Human populationgrowth alone means we have to find ways touse water more economically, because the sameamount of water will have to go around for morepeople. Global warming through climate changeis likely to reduce water availability further. Itis questionable whether we should continue topump an ever scarcer resource into the raisingof livestock . Some 2.5 billion people already livein areas subject to water stress; by 2025, it will beover half of humanity, and conflicts over water areexpected to become more acute.A thirsty industryChinaIndiaUnited KingdomJapanWater use by Nippon Ham, the world’s 6th-largestmeat company, 2011, 100 percent = 12.5 million m 332food plantsfresh meatprocessing plants1.59.756.8Germanylivestock breedingfacilities and feedlotsotherIndonesiaNippon HamSouth AfricaArgentinaTurkeyVirtual waterFranceRussiaMexicoSaudi ArabiaCanadaBrazilIt takes this much water to produce 1 kilogram or 1 litre of:beefcheesericeeggssugarwheatmilkapplesbeerpotatoestomatoescarrots15,455 L5,000 L3,400 L3,300 L1,500 L1,300 L1,000 L700 L300 L255 L184 L131 LItalyAustraliaUSAworld average1 bathtub contains about140 litres of waterwaterfootprint.org Hoekstra/MekonnenMEAT ATLAS29

THE GRAIN IN THE FEED TROUGHRuminants and people do not have to compete over food. But producing moremeat requires ever more grain to feed to animals as concentrates. If we cannotgrow enough at home, we have to import it from abroad.A third of theworld’s cultivatedland is used to growa billion tonnesof feedRuminants and people do not have to competeover food. But producing more meat requiresever more grain to feed to animals asconcentrates. If we cannot grow enough at home,we have to import it from abroad. G rass, silage andhay are low in energy, so to get more out of ouranimals, we feed them with a large amount ofconcentrates: soy, maize (“corn” in the UnitedStates) and other cereals. These contain proteinto improve their fertility and growth, developtheir muscles and boost milk production.But they are low in fibre and lead to more acidproduction in the animals’ rumens. We put additivesinto the feed to compensate.So what do our farm animals eat? The Foodand Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO) says that between 20 and 30 percentof cattle feed can consist of concentrates. A pigtrough may contain anything from 6 to 25 percentsoybean, depending on how old the pigs are.Averaged over all livestock species, only about 40percent of feed comes from grass, hay and silagemade from grass or maize.In Europe, the United States, as well as in Mexico,other parts of Latin America and even in countrieslike Egypt, cattle are no longer fed just ongrass. They also eat maize, wheat and soybeans. Itwould be much more efficient to use these cropsdirectly as food for people. While there are big differencesfrom region to region, worldwide 57 percentof the output of barley, rye, millet, oats andmaize are fed to animals.Even in the United States, where a lot of maizegoes into making ethanol, 44 percent ends up infeeding troughs. In the EU, 45 percent of wheatis used this way. In Africa, especially south of theSahara, where the risk of hunger is highest, suchnumbers are unthinkable. There, people eat 80Virtual trade in land used to grow soybeans for the European UnionIn million hectares, 2008–10 net averageWWFNorth America-1.6Commonwealthof IndependentStatesAsia-2Oceania0.0-0.2South America+0.2Total land outside EU used for soybeans, million hectaresother-0.1ParaguayBrazil-0.9ArgentinaMiddle East/North Africa161412-12.8+0.110-5.4-6.4Sub-SaharanAfrica802001 2005 201030MEAT ATLAS