Fam ily Eco nom ics and - Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion ...

Fam ily Eco nom ics and - Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion ...

Fam ily Eco nom ics and - Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Promotion</strong><strong>Fam</strong> <strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong> <strong>nom</strong> <strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong>Nu tri tion Re viewEdi torJulia M. DinkinsFea tures Edi torMark LinoMan ag ing Edi torJane W. FlemingCon tribu torJoan C. Cour tless<strong>Fam</strong> <strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong> <strong>nom</strong> <strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nu tri tion Re view iswrit ten <strong>and</strong> pub lished each quar ter by theCen ter <strong>for</strong> Nu tri tion Pol icy <strong>and</strong> Pro mo tion,U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wash ing ton, DC.The Sec re tary of Ag ri cul ture has de ter minedthat pub li ca tion of this pe ri odi cal is ne ces saryin the tran sac tion of the pub li c businessre quired by law of the De part ment.This pub li ca tion is not copy righted. Con tentsmay be re printed with out per mis sion, but creditto <strong>Fam</strong> <strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong> <strong>nom</strong> <strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nu tri tion Revieww ould be ap pre ci ated. Use of com mer cial ortrade names does not im ply approval or con sti -tute en dorsement by USDA. <strong>Fam</strong> <strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong> <strong>nom</strong> <strong>ics</strong><strong>and</strong> Nu tri tion Review is indexed in the fol low ingda taba ses: AGRICOLA, Age line, <strong>Eco</strong> <strong>nom</strong>icLit era ture In dex, ERIC, <strong>Fam</strong> <strong>ily</strong> Stud ies,PAIS, <strong>and</strong> So cio logi cal Abstracts.<strong>Fam</strong> <strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong> <strong>nom</strong> <strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nu tri tion Re view is<strong>for</strong> sale by the Su per in ten dent of Docu ments.Sub scrip tion price is $12.00 per year ($15.00<strong>for</strong> <strong>for</strong> eign ad dresses). Send sub scrip tionor ders <strong>and</strong> change of ad dress to Su per in -ten d ent of Docu ments, P.O. Box 371954,Pittsburgh, PA 15250- 7954. (See subscrip tio n<strong>for</strong>m on p. 123.)O rigi nal manu scripts are ac cepted <strong>for</strong> pub li -ca tion. (See “guide lines <strong>for</strong> authors” on backin side cover.) Sug ges tions or com ments con -cerning this pub li ca tion should be ad dressedto Julia M. Dink ins, Edi tor, <strong>Fam</strong> <strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong> <strong>ics</strong><strong>and</strong> Nu tri tion Review, <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> Nu tri tion<strong>Policy</strong> <strong>and</strong> Pro mo tion, USDA,1120 20th St.NW, Suite 200 North Lobby, Wash ing ton, DC20036. Phone (202) 606-4876.The <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Reviewis no w available at http://www.usda.gov/cnpp(see p. 121).Research Ar ti clesSpe cial IssueFood Guide Pyra mid <strong>for</strong> Young Children3 Adapting the Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong> Children:Defining the Target AudienceEtta Saltos18 Technical Research <strong>for</strong> the Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong> Young ChildrenKristin L. Marcoe33 Consumer Research: Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong> Young ChildrenCatherine Tarone45 Factors Influencing Children’s Dietary Practices: A ReviewAlyson Escobar56 Expenditures on Children by <strong>Fam</strong>ilies, 1999Mark LinoResearch Briefs75 Are All Food Pyra mids Cre ated Equal?Alyson Escobar78 Re port Card on the Diet Qual ity of ChildrenMark Lino, Shirley A. Gerrior, P. Peter Basiotis, <strong>and</strong> Rajen S. An<strong>and</strong>81 Eat ing Break fast Greatly Im proves School chil dren’s Diet QualityP. Pe ter Basiotis, Mark Lino, <strong>and</strong> Rajen S. An<strong>and</strong>Research Sum ma ries85 Contribution of Away-From-Home Foods to Ameri can Diet Quality90 The Ru ral Poor’s Ac cess to Su per mar kets <strong>and</strong> Large Gro cery Stores93 Pov erty <strong>and</strong> Well- Being in Rural America96 Al ter na tive Em ploy ment Arrangements101 Fac tors Af fect ing Nu tri ent In take of the Elderly104 The Food Stamp Pro gram Af ter Wel fare Re<strong>for</strong>mRegular Items108 Fed eral Sta tis t<strong>ics</strong>: Chil dren’s Health110 Re search <strong>and</strong> Evalua tion Ac tivi ties in USDA113 Jour nal Abstracts115 USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home116 Con sumer Prices117 U.S. Pov erty Thresholds118 In dex of Ar ti cles in 1999 Issues119 In dex of Authors in 1999 Issues120 Re view ers <strong>for</strong> 1999 ArticlesVolume 12, Numbers 3&41999

The purpose of this study was to definethe target audience <strong>for</strong> a food guide thatwould be adapted <strong>for</strong> children by recommendingsubgroups within the 2- to 18-year age range <strong>and</strong> ranking the subgroupsin order of greatest need based on dietaryrequirements <strong>and</strong> user dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong> nutritioneducation materials. Materialsreviewed <strong>for</strong> this study included journalarticles, reference materials (includingthe Recommended Dietary Allowances<strong>and</strong> nutrition textbooks), <strong>and</strong> published<strong>and</strong> unpublished reports from governmentagencies. Criteria used to define <strong>and</strong> rankthe subgroups included the following:• nutrient needs of children,• nutrition recommendations <strong>for</strong>children by authoritative bodies,such as the Dietary GuidelinesAdvisory Committee,• nutritional status of children,including macronutrient <strong>and</strong> micronutrientintake <strong>and</strong> anthropometricmeasurements, <strong>and</strong>• children’s knowledge <strong>and</strong> attitudesregarding nutrition.These criteria were used to define subgroups<strong>and</strong> to list facts in favor of <strong>and</strong>against adapting a food guide <strong>for</strong> eachsubgroup.Nutrient Needs of ChildrenThe Recommended Dietary Allowances(RDA) provide in<strong>for</strong>mation concerningchildren’s nutrient needs, as well as thenutritional needs of the rest of the population(23). The 1989 RDA are expressed<strong>for</strong> the following age-gender groups:children, ages 1 to 3 years; children,ages 4 to 6 years; children, ages 7 to 10years; males, ages 11 to 14 years; females,ages 11 to 14 years; males, ages 15 to18 years; <strong>and</strong> females, ages 15 to 18years.The National Academy of Sciences’Food <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Board, however, isin the process of replacing these RDAwith new dietary recommendations:Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI). 2DRI were released recently <strong>for</strong> calcium,phosphorus, magnesium, fluoride,vitamin D, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin,vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenicacid, biotin, <strong>and</strong> choline (31,32).Reference intake values were published<strong>for</strong> the following age groups: 1 to 3 years,4 through 8 years, 9 through 13 years,<strong>and</strong> 14 through 18 years.The current RDA (or AI <strong>for</strong> calcium,fluoride, vitamin D, pantothenic acid,biotin, <strong>and</strong> choline) <strong>for</strong> children were(a) extrapolated from infant or adultresearch results (vitamins A, K, C,B6, B12, riboflavin, niacin, folate,biotin, choline, pantothenic acid,selenium, iodine, <strong>and</strong> manganese),(b) based on growth <strong>and</strong> consumptiondata (energy, protein, iron, phosphorus,<strong>and</strong> potassium),(c) estimated based on weight (fluoride<strong>and</strong> vitamin E),2 The DRI, a set of up to four nutrient-based referencevalues, consist of the Estimated AverageRequirement (EAR), Recommended DietaryAllowances (RDA), Adequate Intake (AI), <strong>and</strong>Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL). The EARrefers to the da<strong>ily</strong> intake value that is estimatedto meet the nutrient requirement in half of theindividuals in a given age-gender group. The RDAconsist of the average da<strong>ily</strong> intake level that issufficient to meet the nutrient requirement ofnearly all healthy individuals in the age-gendergroup, based on the EAR. The AI is the da<strong>ily</strong>intake value that is estimated to meet the nutrientrequirement of nearly all healthy individuals in theage-gender group <strong>and</strong> is used when an EAR is notavailable to calculate the RDA. The UL definesthe highest level of nutrient intake that is likely topose no risks of adverse health effects in almostall individuals in the general population.(d) based on studies on balance inchildren, but not necessar<strong>ily</strong> withall the above age groups (thiamin,zinc, copper, sodium, calcium, <strong>and</strong>magnesium), or(e) estimated based on biochemicalmarkers (vitamin D) (23,31,32).Because the RDA/AI <strong>for</strong> children werelargely extrapolated or calculated ratherthan determined directly from studies ofchildren, there is no overriding reason<strong>for</strong> using the RDA age-gender cutoffs<strong>for</strong> a children’s food guide. In<strong>for</strong>mationon children’s dietary intakes, nutritionalstatus, <strong>and</strong> dietary recommendations----as well as in<strong>for</strong>mation on their attitudes,knowledge, <strong>and</strong> behavior----must also beconsidered when determining whichgroups of children are most in need ofnutrition guidance.<strong>Nutrition</strong> Recommendations<strong>for</strong> ChildrenRecommendations of theU.S. GovernmentA number of recommendations indicatewhat constitutes a healthful diet <strong>for</strong>children. The Dietary Guidelines <strong>for</strong>Americans, the basis of Federal nutritionpolicy (39), provide advice about foodchoices that promote health <strong>and</strong> preventdisease among healthy Americans 2 yearsold <strong>and</strong> older. The Guidelines adviseAmericans to eat a varied diet with plentyof grain products, vegetables, <strong>and</strong> fruits,while moderating their intakes of fat,saturated fat, cholesterol, sugars, salt<strong>and</strong> sodium, <strong>and</strong> alcoholic beverages. Inaddition to emphasizing the benefits ofphysical activity, the Guidelines providesome specific advice <strong>for</strong> children: theyshould be taught to eat grain products;vegetables <strong>and</strong> fruits; lowfat milkproducts or other calcium-rich foods;beans, lean meat, poultry, fish or other4 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

protein-rich foods; <strong>and</strong> to participate invigorous physical activity. The Guidelinescaution that fat should not be restricted<strong>for</strong> children younger than age 3 2, thatmajor ef<strong>for</strong>ts to change a child’s dietshould be accompanied by monitoringof growth at regular intervals by a healthprofessional, <strong>and</strong> that children shouldnot consume alcoholic beverages. TheGuidelines also recommend that childrenbetween the ages of 2 <strong>and</strong> 5 shouldgradually adopt a diet so that it containsno more than 30 percent of calories fromfat by the time children are about 5 yearsold (39).The report Healthy People 2010 outlinesa national strategy <strong>for</strong> improving significantlythe health of Americans duringthe 2001 to 2010 decade (42). Includedin the 2010 report is a recommendationto reduce fat intake to an average of 30percent of calories or less <strong>and</strong> saturatedfat intake to an average of less than 10percent of calories among people 2 yearsold <strong>and</strong> older. The National CholesterolEducation Program recommends thattotal fat intake averages no more than30 percent of calories (24). Theserecommendations are consistent withthe advice given in the 1990 DietaryGuidelines; the 1995 Dietary Guidelinesamended this advice, stating that childrenbetween the ages of 2 <strong>and</strong> 5 shouldgradually reduce their total fat intakeso that by age 5, they are consumingno more than 30 percent of caloriesfrom fat.Recommendations ofOther OrganizationsSeveral organizations provide dietaryadvice <strong>for</strong> children that is consistentwith the basic principles of the DietaryGuidelines <strong>for</strong> Americans. The American3 In this paper, the use of the terms ‘‘age’’ <strong>and</strong>‘‘ages’’ refers to age in years, unless statedotherwise.Academy of Pediatr<strong>ics</strong>, <strong>for</strong> example,recommends that children eat a widevariety of foods <strong>and</strong> consume enoughcalories to support growth <strong>and</strong> development<strong>and</strong> to reach or maintain advisablebody weight. The Academy also recommendsthat children over the age of 2consume, on average, 30 percent of totalcalories from fat, less than 10 percent ofcalories from saturated fat, <strong>and</strong> less than300 mg of cholesterol per day. However,the Academy cautions that ‘‘recommendationsthat call <strong>for</strong> ‘less than’ 30 percentof calories from fat may lead to theinappropriate use of more restrictivediets’’ (3).The American Heart Association (AHA)concurs with the recommendation of theDietary Guidelines that children betweenthe ages of 2 <strong>and</strong> 5 gradually adopt adiet containing 30 percent or less ofcalories from fat. The AHA also agreeswith the Dietary Guidelines’ recommendationthat diets of young children shouldmaintain the primary emphasis on providingadequate calories <strong>and</strong> nutrients<strong>for</strong> normal physical activity, growth,<strong>and</strong> development (17).Some disagree about the age at whichchildren should adopt a lower fat diet.A joint working group of the CanadianPaediatric Society <strong>and</strong> Health Canadarecommended a longer transition periodto a diet lower in fat, compared withthat recommended by the Dietary Guidelines.The joint working group advisedthat the transition from the high-fat dietduring infancy (about 50 percent ofcalories from fat) to a diet that includesno more than 30 percent of calories asfat <strong>and</strong> 10 percent of calories as saturatedfat take place between the age of 2 <strong>and</strong>the end of linear growth (about age 14<strong>for</strong> females <strong>and</strong> 15 <strong>for</strong> males) (14). Therationale <strong>for</strong> the working group’s recommendationwas based on (1) lack ofOther studies havealso concludedthat it is safe torecommend that fatintake be limited to30 percent of calories<strong>and</strong> saturated fatintake to less than10 percent of calories<strong>for</strong> children 5 yearsold <strong>and</strong> older . . . .1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 5

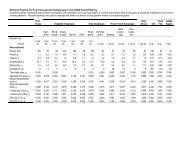

evidence that consuming a diet providing30 percent of calories as fat <strong>and</strong>10 percent of calories as saturated fatwould either reduce illness in later lifeor provide short-term health benefits<strong>and</strong> (2) concerns that some childrenconsuming a diet with low fat intakeshave lower energy intakes <strong>and</strong> lowintakes of some nutrients.To support their position, the CanadianPaediatric Society <strong>and</strong> Health Canadacited a publication from the BogalusaHeart Study in which 24-hour recallswere obtained from about 870 10-yearoldswhose diets were stratified by fatintake: those with less than 30 percentof calories from fat had lower intakesof many nutrients than did children withhigher fat intakes. The children with thelower percentage of calories from fatalso had higher intakes of simple carbohydrates(25). The children enrolled inthe Bogalusa Study had not been exposedpreviously to any dietary interventionprograms. There<strong>for</strong>e, it cannot be concluded,on the basis of the BogalusaStudy, that children----whose parents<strong>and</strong> caregivers have been instructed onhow to moderate dietary fat intake----will be unable to meet their nutrientrequirements on a diet containing 30percent of calories from fat.Other researchers have concluded thatchildren can safely follow diets containing30 percent of calories from fat. TheDietary Intervention Study in Children(DISC) is an ongoing, r<strong>and</strong>omized studythat is a controlled clinical trial of dietscontaining lowered fat, saturated fat,<strong>and</strong> cholesterol. About 660 childrenages 8 to 10 who were enrolled in 6centers, located around the country, wereassigned r<strong>and</strong>omly to either controlgroups or groups receiving behavioralintervention to promote their followinga diet providing 28 percent of caloriesfrom total fat, less than 8 percent ofcalories from saturated fat, <strong>and</strong> less than150 mg of cholesterol (less than 75 mg/1,000 calories) per day. After 3 years,dietary levels of total fat, saturated fat,<strong>and</strong> cholesterol <strong>and</strong> blood levels of lowdensitylipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)decreased significantly in the interventiongroup, compared with the controlgroup. The two groups, however, didnot differ significantly on measures ofgrowth <strong>and</strong> development: Height, redblood-cellfolate values, serum zinc,retinol <strong>and</strong> albumin levels, sexualmaturation, <strong>and</strong> psychosocial health.The DISC study found that childrengrew <strong>and</strong> developed normally afterbeing instructed on consuming a lowerfat diet. The children in the interventiongroup also had lower LDL-C levels thanthe controls. The researchers concluded,there<strong>for</strong>e, that the diet was effective aswell as safe (19). Other studies have alsoconcluded that it is safe to recommendthat fat intake be limited to 30 percentof calories <strong>and</strong> saturated fat intake toless than 10 percent of calories <strong>for</strong>children 5 years old <strong>and</strong> older(26,29,35).Another recommendation regardingchildren’s diets addresses their requirements<strong>for</strong> dietary fiber. The DietaryGuidelines recommend that individuals2 years <strong>and</strong> older choose a diet withplenty of grain products, vegetables,<strong>and</strong> fruits to provide adequate fiber.But the Guidelines do not set specificnumerical goals <strong>for</strong> fiber intake. TheAmerican Health Foundation publisheda recommendation that a child’s fiberintake be equivalent to his or her ageplus 5 grams (g) a day (‘‘age + 5’’),with the recommendation ranging from8 g a day <strong>for</strong> a child age 3 to 25 g a day<strong>for</strong> a person age 20 (44).<strong>Nutrition</strong>al Status of ChildrenDietary Intake----EnergyData on children’s food consumptionare provided by several national surveys:DHHS’s National Health <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong>Examination Survey (NHANES III),USDA’s Continuing Survey of FoodIntakes by Individuals (CSFII), <strong>and</strong> theMarket Research Corporation of America(MRCA) (1,10,16,37). Median energyintakes below 100 percent of the RDA<strong>for</strong> several age-gender groups werereported in NHANES III results (10).The CSFII 1994-96 reported that overhalf of the children 5 years old <strong>and</strong>younger had energy intakes below theRDA, <strong>and</strong> about 20 percent had energyintakes below 75 percent of the RDA.About 60 percent of males <strong>and</strong> 75 percentof females 6 to 19 years old hadenergy intakes below the RDA (37).Rather than a reflection of actual lowintakes of energy by children, these lowintakes of energy could be the result ofunderreporting the foods eaten or oflow energy expenditures by children.Several studies have reported thatpreschool-age children have energyexpenditures lower than the RDA(6,11,12). In contrast, the prevalenceof overweight among children has beenincreasing (36). According to CSFII1994-96, about 5 to 10 percent of allchildren have energy intakes at or above150 percent of the RDA (37).Dietary Intake----Macronutrients<strong>and</strong> FiberFood consumption surveys report that,on average, children are consumingmore than 30 percent of calories fromtotal fat <strong>and</strong> more than 10 percent ofcalories from saturated fat (fig. 1) (1,10,16,37). Kennedy <strong>and</strong> Goldberg, usingCSFII 1989-91 data, reported that overthree-fourths of all children exceeded6 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

Figure 1. Percent of calories from total fat <strong>and</strong> saturated fat in children’s diets exceedsrecommendationsPercent454035302520151050Age <strong>and</strong>gender1-2 years 3-5 years 6-11 yearsmales6-11 yearsfemales12-19 yearsmales12-19 yearsfemales% Calories from total fat% Calories from saturated fatDietary Guidelines recommendation <strong>for</strong> % calories from total fatDietary Guidelines recommendation <strong>for</strong> % calories from saturated fatrecommendations <strong>for</strong> total fat <strong>and</strong>saturated fat (15). Improvement wasslight by 1994, when roughly two-thirdsof all children exceeded the recommendation<strong>for</strong> total fat <strong>and</strong> saturated fat(16). Because of the Guidelines’ recommendation<strong>for</strong> gradual adoption of a dietlow in fat, concern is greater <strong>for</strong> children5 years <strong>and</strong> older than it is <strong>for</strong> children2 to 5 years old. The CSFII 1994-96also reported that adolescent males areconsuming more than 300 mg/day ofcholesterol, the upper limit of cholesterolintake listed on the <strong>Nutrition</strong> Facts label(37).Other studies have confirmed the findingsregarding children’s fat intake: most areconsuming more than the recommendedlevels. About ninety 3- to 5-year-oldchildren enrolled in the FraminghamChildren’s Study 4 consumed an averageof 33 percent of calories from fat (28).Albertson <strong>and</strong> Tobelmann, analyzing1986-88 MRCA data, reported thatamong 825 children ages 7 to 12, thosewho frequently ate ready-to-eat cereal(7 or more times in 14 days) consumeda lower percentage of calories from fat,compared with others who consumedready-to-eat cereals less frequently: 2 to6 times in 14 days or less than 2 timesin 14 days. However, all three groupsconsumed more than 30 percent ofcalories from fat (2).Data from the CSFII 1994-96 showedthat young children’s mean intakes of4 The longitudinal Framingham Children’s Studyexamined factors related to the development ofdietary habits <strong>and</strong> patterns of physical activityduring childhood.dietary fiber met the ‘‘age + 5’’ recommendationof the American HealthFoundation. Children 5 years old <strong>and</strong>younger had mean fiber intakes ofabout 11 g a day. However, older childrenbegan to fall short of the fiber recommendations:males <strong>and</strong> females 6 to 11years old consumed about 14 g <strong>and</strong> 12 gof fiber per day, respectively; their counterparts12 to 19 years old consumed about17 g (males) <strong>and</strong> 13 g (females) per day(37).Dietary Intake----MicronutrientsAmerican children are more likely toget adequate amounts of vitamins <strong>and</strong>minerals than they are to meet DietaryGuideline recommendations <strong>for</strong> total fat<strong>and</strong> saturated fat intake. However, somenutrients are consumed at levels belowrecommended amounts by some groups1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 7

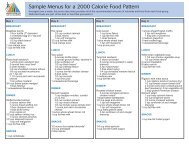

in the U.S. population. For example,vitamin E <strong>and</strong> zinc are consumed atlevels below 100 percent of the RDAby most children 2 to 19 years old (37).According to CSFII 1994-96, on thedays surveyed, only about 60 percentof children 5 years <strong>and</strong> younger, 60 percentof females 6 to 11 years old, <strong>and</strong>only 28 percent of females 12 to 19 yearsold consumed 100 percent or more ofthe RDA <strong>for</strong> iron. Only about one-thirdeach of males <strong>and</strong> females 12 to 19years old consumed 100 percent ormore of the RDA <strong>for</strong> vitamin A (37).Calcium is another nutrient that childrenconsume at levels below recommendations.Average calcium consumption isbelow the 1989 RDA <strong>for</strong> children 12 to19 years old (fig. 2). In 1994-96, abouthalf of the children 11 years old <strong>and</strong>younger consumed 100 percent or moreof the 1989 RDA <strong>for</strong> calcium; just overone-third of males 12 to 19 years old<strong>and</strong> about 15 percent of females 12 to19 years old consumed 100 percent ormore of the calcium RDA (37). Evenfewer children ages 9 <strong>and</strong> older wouldmeet the new Adequate Intake <strong>for</strong> calcium,which increased to 1,300 mg (31).Compared with other children, adolescents,particularly adolescent females,had the greatest problems in meetingtheir nutrient requirements. Adolescentfemales reported the lowest energyintakes in proportion to their energyrequirement (37). Findings of MRCAdata from 1991-94 show that mostadolescents ages 11 to 17 consumed lessthan 2 servings (the minimalnumber recommended) of fruits a day.Twelve percent of adolescents consumedno fruits in a given day (45).Krebs-Smith et al. examined 3-day datafrom CSFII 1989-91 <strong>for</strong> children <strong>and</strong>adolescents 2 to 18 years old. Evenafter foods were separated into theircomponent ingredients (e.g., credit isgiven <strong>for</strong> vegetables in mixed dishes,such as on pizza or in s<strong>and</strong>wiches),only one in five children consumed therecommended 5 servings of fruits <strong>and</strong>vegetables a day. One-quarter of allvegetables that were consumed wereFrench fries. Children from familieswith higher income consumed moreservings of fruits <strong>and</strong> vegetables,compared with children from familieswith lower income (18).Data from the CSFII 1994-96 alsoshowed that children’s intake of fruits<strong>and</strong> vegetables was low. Only aboutone-fourth of children 2 to 11 years oldconsumed the minimal 3 servings ofvegetables a day that are recommendedby the Pyramid, <strong>and</strong> only about 40 percentof females <strong>and</strong> 55 percent of males12 to 19 years old met the minimal numberof servings. About half of all 2- to 5-yearoldsconsumed the minimal 2 servingsof fruit a day recommended by thePyramid, but this dropped to about onefourth<strong>for</strong> males <strong>and</strong> females 11 to 19years old (37). Low intakes from onefood group could explain some of thelow nutrient intakes, particularly <strong>for</strong>vitamins A <strong>and</strong> C <strong>and</strong> folate.Sodium intakes <strong>for</strong> many children arehigher than 2,400 mg a day, its upperlimit (listed on the <strong>Nutrition</strong> Facts label).Children 6 years old <strong>and</strong> older hadmedian sodium intakes greater than2,400 mg a day according to NHANESdata (which includes allowances <strong>for</strong> saltadded at the table <strong>and</strong> sodium in water<strong>and</strong> medications) (10). In the CSFII1994-96 (which reports only sodiumintake from food), the mean sodiumconsumption <strong>for</strong> all children 3 years old<strong>and</strong> older exceeded 2,400 mg a day.Mean sodium consumption <strong>for</strong> males ages12 to 19 years was 4,407 mg a day (37).Anthropometric IndicesWeight <strong>and</strong> height indicators fromNHANES III show that underweight isa concern <strong>for</strong> about 5 percent of 2- to17-year-olds (only 2 percent of 12- to17-year-old females) (10). Overweight,when defined as a weight <strong>for</strong> heightgreater than the 95th percentile, occurredin 10.9 percent of children ages 6 through17 (36). When overweight was definedas a weight <strong>for</strong> height greater than the85th percentile, the incidence of overweightincreased to 22 percent (36).The prevalence of overweight increasedbetween 1963-65 <strong>and</strong> 1988-91 amongall age-gender groups, with the greatestincrease occurring between 1976-80 <strong>and</strong>1988-91 (36).A study of the prevalence of overweightamong preschool-age children 2 monthsthrough 5 years old found that overweightamong 4- <strong>and</strong> 5-year-old females increasedfrom 5.8 percent in 1971-74 to10 percent in 1988-94. Overweight wasdefined, in this study of NHANES data,as being above the 95 th percentile of theappropriate measures of the National<strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> Health Statist<strong>ics</strong>: weight<strong>for</strong>-lengthor weight-<strong>for</strong>-stature growthcurve. The prevalence of overweight didnot increase among younger children.However, the increase in prevalence ofoverweight in children as young as 4 yearsold suggests that ef<strong>for</strong>ts to prevent overweightshould begin in early childhood(27).The increase in obesity is surprising,because many children are reportingenergy intakes below the RDA. Lackof physical activity may be responsible<strong>for</strong> the increase, <strong>and</strong> the number of hourschildren watch television has been linkedto obesity in this age group (8).8 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

Figure 2. Mean calcium intakes of older American children below recommended levelsMilligrams1400120010008006004002000Age <strong>and</strong>gender1-2 years 3-5 years 6-11 yearsmales6-11 yearsfemales12-19 yearsmales12-19 yearsfemalesCalcium intake, mg 1989 RDA, mg 1997 AI, mgConsumer Research----Children’s Knowledge <strong>and</strong>Attitudes About <strong>Nutrition</strong>When adapting a food guide <strong>for</strong> children,USDA staff believe it is useful to findout what children know about nutrition,what their attitudes are about foods <strong>and</strong>nutrition, <strong>and</strong> what nutrition educationprograms have been successful. Childrenhave been the target audience <strong>for</strong> somequalitative <strong>and</strong> quantitative studies;however, in<strong>for</strong>mation about their knowledge<strong>and</strong> attitudes regarding nutrition isfar more scarce than in<strong>for</strong>mation aboutadult’s knowledge <strong>and</strong> attitudes.Qualitative StudiesIn late 1991, in preparation <strong>for</strong> developingnutrition labeling materials <strong>for</strong> children,KIDSNET, Inc., an organization workingon children’s educational issues (in cooperationwith the U.S. Food <strong>and</strong> DrugAdministration [FDA]), sponsored minifocusgroups (3 children in each group)with children 6, 8, <strong>and</strong> 12 years old. Thefocus groups were designed to examinechildren’s attitudes <strong>and</strong> behavior regardingfood, as well as their awareness <strong>and</strong>knowledge of the relationship betweennutrition <strong>and</strong> food. Six focus groups (witha mixture of racial <strong>and</strong> income groups)were conducted in the Washington, DC,area. The children reported having someinfluence over the foods they eat, particularlybreakfast cereals, snack foods,<strong>and</strong> lunches. Some 6-year-olds evenreported making their own lunches.Results from the mini-focus group showedthat the children’s age influenced theirknowledge of nutrition. Twelve-year-oldchildren could name food groups <strong>and</strong>were aware that carbohydrate, protein,fat, vitamins, <strong>and</strong> minerals are found infood. Younger children did not have aclear underst<strong>and</strong>ing of food groups, <strong>and</strong>many children thought of vitamins asproducts that come in a bottle from thedrugstore. However, even though the12-year-old children were fairly knowledgeableabout nutrition, their knowledgedid not carry over to their own dietarypatterns. Taste, instead, was their primaryconsideration in making food choices.In the words of one 12-year-old participant:‘‘We hear ‘Eat right. Don’t dodrugs.’ It’s getting boring, like a brokenrecord, so we just tune it out’’ (30).1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 9

. . . the increase inprevalence of overweightin children asyoung as 4 years oldsuggests that ef<strong>for</strong>tsto prevent overweightshould begin in earlychildhood . . . .The FDA sponsored two focus groups,each consisting of six to eight females13 to 15 years old from various racial<strong>and</strong> ethnic groups. The purpose of thefocus groups was to determine the typesof nutrition messages the participantswould find compelling <strong>and</strong> to determinewhich <strong>for</strong>mat(s)----<strong>for</strong> messages aboutcalcium----the participants would mostlikely pay attention to. These focusgroups were held in the Washington,DC/Baltimore, MD, metropolitan area.The results revealed that the participantshad a fairly good knowledge of nutrition;they could name nutrients <strong>and</strong> makeassociations between a nutrient <strong>and</strong> itsfunction, <strong>for</strong> example, ‘‘calcium makesyour bones strong.’’ Participants saidthey tended to pay more attention toeating a healthful diet when they wereactively involved in a sport. (Most wereactive in at least one sport.) A frequentlymentioned barrier to healthful eatingwas related to school lunches: lunchperiods were often rushed <strong>and</strong> at oddhours of the day. Participants expresseda preference <strong>for</strong> educational materialsthat contained bold, bright colors <strong>and</strong>little or no text (21).The International Food In<strong>for</strong>mationCouncil sponsored one focus group with9- to 12-year-old children <strong>and</strong> anotherwith 13- <strong>and</strong> 14-year-olds to evaluate aprototype nutrition brochure. All of theparticipants had seen the Food GuidePyramid, <strong>and</strong> all said they already knewabout the importance of eating vegetables,fruits, <strong>and</strong> grain products. The participants,however, believed these conceptswere ‘‘boring, because everyone knowsthat,’’ <strong>and</strong> they believed that in<strong>for</strong>mationabout eating breakfast, smart snacking,<strong>and</strong> balance was important. They alsothought in<strong>for</strong>mation about physicalactivity was important but believed thatactivities portrayed should be relevantto their age group. Activities such asgolf <strong>and</strong> racquetball were perceivedas ‘‘adult’’ sports (9).Because these studies were conductedusing locally available samples <strong>and</strong>were conducted in urban areas, theresults must be interpreted cautiously<strong>and</strong> cannot be generalized to all children.Quantitative StudiesThe Kellogg Company surveyed childrenabout their nutrition knowledge, attitudes,<strong>and</strong> behavior. A nationally representativeschool-based survey was conducted in1988-89 with 5,000 students in Grades3 through 12. Over half of the respondentsin this survey believed nutrition is‘‘very important’’; however, nutritionwas considered less important by olderchildren than by younger ones. Almostthree-quarters of elementary schoolstudents considered nutrition ‘‘veryimportant,’’ compared with about halfof junior high school students <strong>and</strong> onlyabout one-third of high school students(13).The Kellogg survey also found that thepositive attitudes of many children didnot always translate into appropriatebehavior, confirming the results of thequalitative studies referred to earlier inthis paper. Only about one-third of allschool-age children responded ‘‘often’’(rather than ‘‘sometimes’’ or ‘‘rarely’’)to the statement ‘‘I eat the right foods.’’Children who agreed strongly with thestatement that too much cholesterol <strong>and</strong>saturated fat are bad <strong>for</strong> health reportedeating foods high in these componentsas often as did other children, thus demonstratingthat their knowledge did notchange their behavior. The authors ofthe Kellogg survey suggested that lackof sufficient knowledge could be partiallyresponsible <strong>for</strong> this disconnect----the children might know that excessive10 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

dietary cholesterol <strong>and</strong> saturated fat areunhealthful, but they may not knowwhich foods are rich sources of thesecomponents (13).Lack of adult supervision could alsoaccount <strong>for</strong> some of the poor eatinghabits reported by the participants ofthe Kellogg survey. About 60 percentof children reported coming home to anempty house at least once a week, withmore than one-third coming home alonethree or more times a week. These‘‘latchkey’’ children were more likelyto report that they, rather than theirparents, have more control over whatthey eat (60 percent of ‘‘latchkey’’children; 35 percent of all elementaryschoolchildren).Eating away from home frequently couldinfluence children’s diets. According toUSDA’s CSFII 1994-96, about 40 percentof children 5 years old <strong>and</strong> younger<strong>and</strong> over two-thirds of children 6 to 19years old reported eating at least onefood item away from home on the dayof the survey. The most frequentlymentioned sources of food away fromhome were fast-food restaurants, schoolor day care, someone else or gift, <strong>and</strong>stores (37).The Kellogg Survey also found thatalmost one-third of school-age childrenbelieved they were overweight (13).This figure is somewhat higher than the22 percent of children 6 to 17 years oldwho were found to be overweight byNHANES III. This difference raises apossibility: some children whose weightis normal think they are overweight.Thus dieting is a common behavioramong children; about 40 percent ofall school-age children participatingin the Kellogg Survey reported havingbeen on a diet. More females than malesreported dieting, <strong>and</strong> most of the childrenwho reported dieting did so <strong>for</strong> cosmeticreasons rather than <strong>for</strong> health (13).Lack of physical activity has been citedas a possible reason <strong>for</strong> the increase inthe percentage of children who are overweight(6,8,11,12). The Kellogg Survey,on the other h<strong>and</strong>, found that schoolchildrendo consider exercise to beimportant. Elementary schoolchildrenreported taking part in physical activityover five times a week; high schoolstudents reported being involved inphysical activity about four times aweek (13).The Youth Risk Behavior Survey, acomponent of the Youth Risk BehaviorSurveillance System (<strong>Center</strong>s <strong>for</strong> DiseaseControl <strong>and</strong> Prevention), is a nationalschool-based survey of students inGrades 9 through 12. It contains a seriesof questions, parts of which are nutritionordiet-related. Male students respondingto this survey were significantly morelikely than female students to considerthemselves the ‘‘right weight’’ or‘‘underweight’’ (86 vs. 66 percent).Female students were significantly morelikely than male students to report tryingto lose weight at the time of the survey(44 vs. 15 percent). Over one-fourth offemale students who considered themselvesthe ‘‘right weight’’ reported tryingto lose weight. And female studentswere significantly more likely thantheir male counterparts to report eithercurrently or ever having used inappropriatepractices to lose weight: such as,skipping meals, taking diet pills, orinducing vomiting (40).The Youth Risk Behavior Survey askedstudents in Grades 9 through 12 how oftenthey participated in vigorous activity inthe 2 weeks preceding the survey. Vigorousactivity was defined as ‘‘at least 20minutes of hard exercise that made youbreathe heav<strong>ily</strong> <strong>and</strong> made your heartbeat fast’’ (41). About one-third of allstudents reported being vigorouslyactive three or more times a week, butfemale students were half as likely thanmale students to report regular vigorousactivity (25 vs. 50 percent), <strong>and</strong> AfricanAmerican students were less likely thanWhite or Hispanic students to reportregular vigorous activity (30 vs. 40 <strong>and</strong>35 percent, respectively) (41).Studies of <strong>Nutrition</strong> EducationPrograms----What WorksUSDA conducted research to evaluateadults’ comprehension <strong>and</strong> perceivedusefulness of its food guide <strong>and</strong> todevelop a graphic presentation of thefood guide (43). USDA also conductedresearch to determine the effectivenessof the resulting graphic of the FoodGuide Pyramid with three target audiences:children, consumers with lessthan a high school education, <strong>and</strong> lowincomeconsumers. USDA, in 1991,collaborated with DHHS <strong>and</strong> contractedwith private industry (4) to develop <strong>and</strong>test graphic alternatives (including abowl, shopping cart, <strong>and</strong> dinner plate) tothe Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong> conveyingthe key concepts of variety, proportionality,<strong>and</strong> moderation.Qualitative findings indicated thatchildren preferred the Pyramid graphicto the alternatives tested. They, as well,learned the most in<strong>for</strong>mation from thePyramid. Teachers also preferred thePyramid as a teaching tool, comparedwith the alternatives (4). For the quantitativephase of the research, interviewersquestioned 3,017 individuals, including1,523 children in Grades 2 through 10.The children’s responses to the 60-itemquestionnaire indicated that the Pyramidgraphic conveyed the concepts of variety,proportionality, <strong>and</strong> moderation.Younger children (Grades 2 to 3),1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 11

The <strong>Center</strong> selectedthe preschool-agegroup (2 to 6 years)as the target audience<strong>for</strong> an adapted foodguide . . . .however, understood variety more sothan proportionality <strong>and</strong> moderation (4).Effectiveness of <strong>Nutrition</strong>Education ProgramsThe Food Guide Pyramid adapted <strong>for</strong>children needed to integrate relevantfindings from a recent comprehensivereview on the effectiveness of methodsused in nutrition education. This reviewrevealed that programs using educationalmethods directed at behavioralchange as a goal were more likely thanother programs to be successful----thatis, they were more likely to result in somebehavioral change than were programsthat focused on only distributingin<strong>for</strong>mation (5).Contento et al. recommended that programsbe behaviorally based <strong>and</strong> appropriatelydesigned <strong>for</strong> the child’s stageof cognitive development (5). Preschool<strong>and</strong> early elementary school-age children(4 to 7 years) need activities that allowthem to modify their environment. Providingfood-based activities <strong>and</strong> havingadults model eating behavior are appropriate<strong>for</strong> this age group. Also, parents’or other caregivers’ involvement withchildren in this age group is an importantfactor contributing to success. Olderelementary school-age children (8 throughabout 11 years) still need to have in<strong>for</strong>mationpresented in concrete terms.Food-classification activities <strong>and</strong> modelingby adults are appropriate <strong>for</strong> this agegroup, <strong>and</strong> involvement with parents<strong>and</strong> the community is still important <strong>for</strong>programs targeted <strong>for</strong> this age group.Adolescents (second decade of life)move from concrete to abstract thinking<strong>and</strong> are able to comprehend more abstractin<strong>for</strong>mation, such as the relationshipbetween diet <strong>and</strong> health----present <strong>and</strong>future. They need activities that encouragecritical thinking, such as exploringthe influence of diet on health <strong>and</strong> theenvironment. With this age group, parents’involvement becomes less important,because adolescents are more likely tobe influenced by their peers than bytheir parents or caregivers (5).The quantity <strong>and</strong> quality of existingnutrition education materials <strong>for</strong> specificage groups of children must alsobe considered when selecting a targetaudience. Recently, Swadener reviewedresearch related to nutrition education<strong>for</strong> preschool-age children (33), <strong>and</strong>Lytle reviewed research related to nutritioneducation <strong>for</strong> school-age children(20). Both found that while many nutritioneducation materials are directedtoward children, improvements <strong>and</strong>follow-up are needed to determinewhether the materials are really effective.Swadener found that many nutritioneducation materials developed <strong>for</strong> preschoolchildrendid not include an evaluationcomponent, many programs werenot conducted <strong>for</strong> a sufficient time toresult in changes in attitudes or behavior,<strong>and</strong> few programs were designed <strong>for</strong>use with children from dysfunctional ormarginally functional families. Lytleconcluded that more tools are needed<strong>for</strong> assessment of change in children’s<strong>and</strong> adolescents’ eating behavior <strong>and</strong>that adolescents, in particular, couldbenefit from exposure to strategies thatmodify behavior. Lytle also found thatmore programs are needed: ones thattarget multi-ethnic groups as well asinvolve families of school-age children.12 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

Pros <strong>and</strong> cons of adapting the Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong> use with three groups of childrenProsHave special needs, re: fat, smaller serving sizesPeer pressure not a problemConsPreschool age (2 through 6 years)Educational materials must target parents <strong>and</strong> caregivers, not childdirectlyFat message (children this age need more fat) may confuse parents,because this need is temporaryCan reach them through the Special Supplemental Feeding Program<strong>for</strong> Women, Infants, <strong>and</strong> Children <strong>and</strong> the Child <strong>and</strong> Adult CareFeeding ProgramDevelopmentally a good time to reach (e.g., when food habits are stillbeing <strong>for</strong>med)Can counteract exposure to television advertising of high-caloriefoodsNot as many materials targeting this age group as <strong>for</strong> older childrenElementary school age (7 through 11 years)Think nutrition is important but don’t act on it; they are ‘‘reachable’’ Already a large amount of nutrition education material available <strong>for</strong>this audience (however, not all of it is relevant or appropriate)Beginning to take more responsibility <strong>for</strong> their own food choicesCurrent food guide already meets nutrient needsEasier to reach (through a single classroom teacher) than youngeror older children (where nutrition education may be provided by adiverse group of individuals)More problems meeting nutrient needsNot many materials targeting this audienceMake many of own food choicesAdolescents (12 to 18 years)Current food guide already meets nutrient needsDifficult audience to reach----need different ways to communicatefood guide, not necessar<strong>ily</strong> different food guideNeed more individualized messages----e.g., <strong>for</strong> athletes vs. nonathletesPerhaps can turn weight concerns into motivation <strong>for</strong> change1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 13

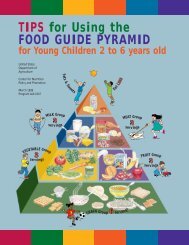

Decision Point----TargetAudience <strong>for</strong> the Food GuidePyramid <strong>for</strong> ChildrenBecause of differences in nutrient needs(23,31,32), current food consumptionpatterns (10,16,37), <strong>and</strong> stages of educationaldevelopment (5), a single foodguide cannot meet the needs of all children2 to 18 years old. Based on children’snutrient needs <strong>and</strong> developmental level,staff of the <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> <strong>Policy</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Promotion</strong> identified three age groups<strong>for</strong> which a Pyramid could be developed:• Preschool <strong>and</strong> early elementary age(2 through 6 years)• Elementary school age (7 through11 years)• Middle <strong>and</strong> high school age (12 to18 years)The <strong>Center</strong> staff considered severalfactors when deciding which age groupshould be targeted <strong>for</strong> an adapted foodguide:• Does the existing food guide meetthis group’s dietary needs, or doesthis group have specific nutritional<strong>and</strong> health problems that an adaptedfood guide could help to address?• If the existing food guide meets thegroup’s dietary needs, has it beensuccessful in influencing the group’sbehavior? Is there a need <strong>for</strong> analternate presentation of the existingfood guide to better reach this group?• What nutrition education materialsexist <strong>for</strong> this audience?• What are the educational considerations<strong>for</strong> this group? Will childrenbe able to use the new food guidedirectly? Will they use the materialswith guidance from a parent orcaregiver? Or will the materialsbe developed <strong>for</strong> the parent orcaregiver?• Is there user dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong> a new foodguide <strong>for</strong> this group?• What is the social effect of thedecision? Will different food guides<strong>for</strong> different ages create confusion?Based on these factors, <strong>Center</strong> stafflisted pros <strong>and</strong> cons <strong>for</strong> developing anadapted food guide <strong>for</strong> each age group(table) <strong>and</strong> considered these issues whenmaking the decision regarding the targetaudience.Implications <strong>and</strong>Recommendations <strong>for</strong> aFood Guide <strong>for</strong> Preschool-AgeChildren (2 to 6 Years)The <strong>Center</strong> selected the preschool-agegroup (2 to 6 years) as the target audience<strong>for</strong> an adapted food guide because thereis a greater need <strong>for</strong> verifying the scientificbasis of the food guide, both froma physiological <strong>and</strong> developmental viewpoint<strong>for</strong> 2- to 6-year-olds than <strong>for</strong> olderchildren. The rationale <strong>for</strong> this conclusionfollows:• Nutrient needs of preschool-agechildren differ from those of olderchildren. The Dietary Guidelines <strong>for</strong>Americans recommend that the levelof dietary fat be gradually decreasedfrom current levels (about 34 percentof calories from fat) to 30 percentof calories by the time the child isabout 5 years old (39). Concernsabout undue food <strong>and</strong> fat restrictions<strong>for</strong> children in this age group, leadingto ‘‘failure to thrive,’’ have beenexpressed by the American Academyof Pediatr<strong>ics</strong> (3). Because the currentFood Guide Pyramid assumes adietary fat intake of 30 percent ofcalories, <strong>Center</strong> staff concluded thatadditional guidance is needed <strong>for</strong>parents <strong>and</strong> caregivers of childrenless than 5 years old.• Following the release of the FoodGuide Pyramid, USDA receivednumerous questions from the ExtensionService; the Dairy Council; theSpecial Supplemental Food Program<strong>for</strong> Women, Infants, <strong>and</strong> Children(WIC); the Child <strong>and</strong> Adult CareFood Program; <strong>and</strong> the media. Theconcern: how to use the food guidewith young children, particularlyregarding children’s need <strong>for</strong> smallerserving sizes.• Developmental concerns regardingfood activities at the preschool levelinclude determining what youngchildren can or should ‘‘learn’’ <strong>and</strong>addressing the physiological <strong>and</strong>emotional issues related to food.Because parents <strong>and</strong> caregivers havea major role in food selection <strong>for</strong>this age group, <strong>Center</strong> staff believedthese children’s attitudes <strong>and</strong> behaviormust also be considered.Adaptation of the food guide <strong>for</strong> thisage group uses the same framework offood groups as the original food guide.Thus the framework blends into laterlearning activities in school whereconcepts are added, <strong>for</strong> example, nutrientcontent of different types of foods;how foods are grown, processed, <strong>and</strong>delivered; how different food itemsare used in different cultures; <strong>and</strong> how‘‘new’’ foods have been historicallyintroduced into the American diet.Using the same framework of foodgroups also makes the new food guidemore practical <strong>for</strong> fam<strong>ily</strong> food managersto use. The process used to adapt thefood guide <strong>for</strong> the preschool <strong>and</strong> earlyelementary-age audience is describedelsewhere in this issue (22,34).14 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

References1. Albertson, A.M., Tobelmann, R.C., <strong>and</strong> Engstrom, A. 1992. Nutrient intakes of 2- to 10-year-old American children: 10-year trends. Journal of the American Dietetic Association92:1492-1496.2. Albertson, A.M. <strong>and</strong> Tobelmann, R.C. 1993. Impact of ready-to-eat cereal consumption onthe diets of children 7-12 years old. Cereal Foods World 38(6):428-431.3. American Academy of Pediatr<strong>ics</strong>, Committee on <strong>Nutrition</strong>. 1998. Statement on cholesterol.Pediatr<strong>ics</strong> 101:141-147.4. Bell Associates, Inc. 1992. An Evaluation of Dietary Guidance Graphic Alternatives.Prepared <strong>for</strong> U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food <strong>and</strong> Consumer Services.5. Contento, I., Balch, G.I., Bronner, Y.L., Paige, D.M., Gross, S.M., Bisignani, L., Lytle, L.A.,Maloney, S.K., White, S.L., Olson, C.M., Swadener, S.S., <strong>and</strong> R<strong>and</strong>ell, J.S. 1995. The effectivenessof nutrition education <strong>and</strong> implications <strong>for</strong> nutrition education policy, programs, <strong>and</strong>research: A review of research. Journal of <strong>Nutrition</strong> Education 27(6):277-422.6. Davies, P.S.W., Gregory, J., <strong>and</strong> White, A. 1995. Energy expenditure in children aged 1.5to 4.5 years: A comparison with current recommendations <strong>for</strong> energy intake. European Journalof Clinical <strong>Nutrition</strong> 49:360-364.7. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. 1995. Report of the Dietary Guidelines AdvisoryCommittee on the Dietary Guidelines <strong>for</strong> Americans. U.S. Department of Agriculture,Agricultural Research Service.8. Dietz, W.H. Jr. <strong>and</strong> Gortmaker, S.L. 1985. Do we fatten our children at the television set?Obesity <strong>and</strong> television viewing in children <strong>and</strong> adolescents. Pediatr<strong>ics</strong> 75:807-812.9. Edelman Public Relations Worldwide. 1995. Report of Focus Groups at Stevens Elementary<strong>and</strong> Poe Middle School. Topline report submitted to International Food In<strong>for</strong>mation Council.10. Federation of American Societies <strong>for</strong> Experimental Biology, Life Sciences ResearchOffice. Prepared <strong>for</strong> the Interagency Board <strong>for</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Monitoring <strong>and</strong> Related Research.1995. Third Report on <strong>Nutrition</strong> Monitoring in the United States: Volume 1. U.S. GovernmentPrinting Office, Washington, DC, 365 pp.11. Fontvielle, A.M., Harper, I.T., Ferraro, R.T., Spraul, M., <strong>and</strong> Ravussin, E. 1993. Da<strong>ily</strong>energy expenditure by five-year-old children, measured by doubly labeled water. Journal ofPediatr<strong>ics</strong> 123:200-207.12. Goran, M.I., Carpenter, W.H., <strong>and</strong> Poehlman, E.T. 1993. Total energy expenditure in4- to 6-year-old children. American Journal of Physiology 264:E706-E711.13. Harris/Scholastic Research. 1989. The Kellogg Children’s <strong>Nutrition</strong> Survey. Conducted<strong>for</strong> the Kellogg Company, Battle Creek, Michigan.14. Joint Working Group of the Canadian Paediatric Society <strong>and</strong> Health Canada. 1993. <strong>Nutrition</strong>Recommendations Update . . . Dietary Fat <strong>and</strong> Children. Ottawa, Ontario: Health Canada,Cat. H39-162/1-1993E. 18 pp.15. Kennedy, E. <strong>and</strong> Goldberg, J. 1995. What are American children eating? Implications <strong>for</strong>public policy. <strong>Nutrition</strong> Reviews 53(5):111-126.1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 15

16. Kennedy, E. <strong>and</strong> Powell, R. 1997. Changing eating patterns of American children: A viewfrom 1996. Journal of the American College of <strong>Nutrition</strong> 16(6):524-529.17. Krauss, R.K., Deckelbaum, R.J., Ernst, N., Fisher, E., Howard, B.V., Knopp, R.H.,Kotchen, T., Lichtenstein, A.H., McGill, H.C., Pearson, T.A., Prewitt, T.E., Stone, N.J.,Van Horn, L., <strong>and</strong> Weinberg, R. 1996. Dietary Guidelines <strong>for</strong> healthy American adults: Astatement <strong>for</strong> health professionals from the <strong>Nutrition</strong> Committee, American Heart Association.Circulation 94:1795-1800.18. Krebs-Smith, S.M., Cook, A., Subar, A.F., Clevel<strong>and</strong>, L., Friday, J., <strong>and</strong> Kahle, L.L.1996. Fruit & vegetable intakes of children <strong>and</strong> adolescents in the United States. Archives ofPediatric <strong>and</strong> Adolescent Medicine 150:81-86.19. Lauer, R.M., Obarzanek, E., Kwiterovich, P.O., Kimm, S.Y.S., Hunsburger, S.A., Barton,B.A., van Horn, B., Stevens, V.J., Lasser, N.L., Robson, A.M., Franklin, F.A., <strong>and</strong> Simons-Morton, D.G. 1996. Efficacy <strong>and</strong> safety of lowering dietary intake of fat <strong>and</strong> cholesterol inchildren with elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: The Dietary Intervention Study inChildren (DISC). Journal of the American Medical Association 273:1429-1435.20. Lytle, L.A. 1994. <strong>Nutrition</strong> Education <strong>for</strong> School-Aged Children: A Review of Research.Report prepared <strong>for</strong> U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food <strong>and</strong> Consumer Service.21. Macro International. 1995. Adolescent Consumers’ Attitudes Toward Calcium Education<strong>and</strong> Proposed Educational Materials: Focus Groups Report. Prepared <strong>for</strong> the U.S. Food <strong>and</strong>Drug Administration.22. Marcoe, K.L. 1999. Technical research <strong>for</strong> the Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong> Young Children.<strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review 12(3&4):18-32.23. National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council, Food <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Board.1989. Recommended Dietary Allowances (10th ed.). National Academy Press, Washington, DC.24. National Cholesterol Education Program. 1991. Report of the Expert Panel on BloodCholesterol Levels in Children <strong>and</strong> Adolescents. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health,NIH Publication no. 91-2732. 119 pp.25. Nicklas, T.A., Webber, L.S., Koschak, M.L., <strong>and</strong> Berenson, G.S. 1992. Nutrient adequacyof low fat intakes <strong>for</strong> children: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatr<strong>ics</strong> 89(2):221-228.26. Niinikoski, H., Lapinleimu, H., Viikari, J., Ronnemaa, T., Jokinen, E., Seppanen, R.,Terho, P., Tuominen, J., Valimaki, I., <strong>and</strong> Simell, O. 1997. Growth until 3 years of age in aprospective, r<strong>and</strong>omized trial of a diet with reduced saturated fat <strong>and</strong> cholesterol. Pediatr<strong>ics</strong>99(5):687-694.27. Odgen, C.L., Troiano, R.P., Briefel, R.R., Kuczmarski, R.J., Flegal, K.M., <strong>and</strong> Johnson,C.L. 1997. Prevalence of overweight among preschool children in the United States, 1971through 1994. Pediatr<strong>ics</strong> 99(4):e1.28. Oliveria, S.A., Ellison, R.C., Moore, L.L., Gillman, M.W., Garrahie, E.J., <strong>and</strong> Singer,M.R. 1992. Parent-child relationships in nutrient intake: The Framingham Children’s Study.American Journal of Clinical <strong>Nutrition</strong> 56:593-598.29. Shea, S., Basch, C.E., Stein, A.D., Contento, I.R., Irigoyen, M., <strong>and</strong> Zybert, P. 1993. Isthere a relationship between dietary fat <strong>and</strong> stature or growth in children three to five years ofage? Pediatr<strong>ics</strong> 92(4):579-586.16 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

30. Shugoll Research. 1992. Children’s <strong>Nutrition</strong> Label Focus Group Study. Report prepared<strong>for</strong> KIDSNET, Inc., Washington, DC.31. St<strong>and</strong>ing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food <strong>and</strong><strong>Nutrition</strong> Board, Institute of Medicine. 1997. Dietary Reference Intakes <strong>for</strong> Calcium, Phosphorus,Magnesium, Vitamin D, <strong>and</strong> Fluoride. Washington, DC. National Academy Press.32. St<strong>and</strong>ing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food <strong>and</strong><strong>Nutrition</strong> Board, Institute of Medicine. 1998. Dietary Reference Intakes <strong>for</strong> Folate, Other BVitamins, <strong>and</strong> Choline. Washington, DC. National Academy Press.33. Swadener, S.S. 1994. <strong>Nutrition</strong> Education <strong>for</strong> Preschool Children: A Review of Research.Report prepared <strong>for</strong> U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food <strong>and</strong> Consumer Service.34. Tarone, C. 1999. Focus group research on adapting the Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong> YoungChildren. <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review 12(3&4):33-44.35. Tonstad, S. <strong>and</strong> Sivertsen, M. 1997. Relation between dietary fat <strong>and</strong> energy <strong>and</strong> micronutrientintakes. Archives of Diseases of Childhood 76(5):416-442.36. Troiano, R.P., Flegal, K.M., Kuczmarski, R.J., Campbell, S.M., <strong>and</strong> Johnson, C.L. 1995.Overweight prevalence <strong>and</strong> trends <strong>for</strong> children <strong>and</strong> adolescents: The National Health <strong>and</strong><strong>Nutrition</strong> Examination Surveys, 1963 to 1991. Archives of Pediatric <strong>and</strong> Adolescent Medicine149:1085-1091.37. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 1998. Food <strong>and</strong> NutrientIntakes by Individuals in the United States by Sex <strong>and</strong> Age, 1994-96, Nationwide Food Surveys.Report No. 96-2. 197 pp.38. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Human <strong>Nutrition</strong> In<strong>for</strong>mation Service. 1992. The FoodGuide Pyramid. Home <strong>and</strong> Garden Bulletin No. 252.39. U.S. Department of Agriculture <strong>and</strong> U.S. Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Human Services. 1995.<strong>Nutrition</strong> <strong>and</strong> Your Health: Dietary Guidelines <strong>for</strong> Americans (4th ed.). U.S. Department ofAgriculture. Home <strong>and</strong> Garden Bulletin No. 232.40. U.S. Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Human Services. 1991. Body-weight perceptions <strong>and</strong>selected weight-management goals <strong>and</strong> practices of high school students----United States,1990. Morbidity <strong>and</strong> Mortality Weekly Reports 40:741,747-750.41. U.S. Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Human Services. 1992. Vigorous physical activity amonghigh school students----United States, 1990. Morbidity <strong>and</strong> Mortality Weekly Reports 41:33-35.42. U.S. Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Human Services. 2000. Healthy People 2010 (ConferenceEdition in Two Volumes). Washington, DC.43. Welsh, S.O., Davis, C., <strong>and</strong> Shaw, A. 1993. USDA’s Food Guide: Background <strong>and</strong>Development. U.S. Department of Agriculture. HNIS Miscellaneous Publication No. 1514.44. Williams, C.L. 1995. Importance of dietary fiber in childhood. Journal of the AmericanDietetic Association 95:1140-1146, 1149.45. Zizza, C.A. <strong>and</strong> Powell, R. 1996. Characterist<strong>ics</strong> distinguishing adolescents by fruitconsumption. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 96:A-91.1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 17

Technical Research <strong>for</strong> theFood Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong>Young ChildrenKristin L. Marcoe<strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> <strong>Policy</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Promotion</strong>This article describes the technical research <strong>for</strong> the Food Guide Pyramid <strong>for</strong>Young Children. Composites <strong>for</strong> food groups <strong>and</strong> subgroups were developedusing food intake data <strong>for</strong> children 2 to 6 years old. Data were from theContinuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals 1989-91. The compositeswere used in creating 1,300- <strong>and</strong> 1,600-calorie Food Guide Pyramid dietpatterns. For children 4 to 6 years old, the 1,600-calorie pattern met allnutrient requirements, except <strong>for</strong> vitamin E. The 1,300-calorie pattern providedthe RDA <strong>for</strong> most nutrients <strong>for</strong> 2- to 3-year-olds <strong>and</strong> 4- to 6-year-olds.The major exceptions were iron <strong>and</strong> zinc <strong>for</strong> both age groups <strong>and</strong> copper<strong>and</strong> vitamin E <strong>for</strong> the 4- to 6-year-olds. When breakfast cereals <strong>for</strong>tifiedwith iron <strong>and</strong> zinc were used in the grain composites, the patterns providedrecommended levels of these nutrients. Children could improve their diet bymaking different food choices, in particular, by eating more dark-green <strong>and</strong>deep-yellow vegetables; legumes; whole grains; <strong>and</strong> lean meat, poultry, orfish.The Food Guide Pyramid<strong>for</strong> Young Children ages2 to 6 years is a nutritioneducation tool to helpteach healthful eating concepts to youngchildren. The technical research conductedin developing <strong>and</strong> documentingthe research base <strong>for</strong> this food guidefollowed procedures similar to thosedescribed in the development <strong>and</strong>documentation of the original foodguide (1,9). Food selections <strong>and</strong> servingsizes reported <strong>for</strong> young children, ina national food consumption survey,were incorporated into diet patternsbased on the Food Guide Pyramid todetermine whether such patterns wouldmeet nutritional goals.A composite was developed <strong>for</strong> eachPyramid food group (e.g., meat, poultry,fish) or subgroup (e.g., whole grain).Composites were based on children’sactual food choices <strong>and</strong> reflected therelative use of individual foods withinthe group or subgroup. An example: thecomposite <strong>for</strong> deep-yellow vegetablesreflected children’s consumption of89 percent as carrots <strong>and</strong> 11 percent asother deep-yellow vegetables. A nutrientprofile was then calculated <strong>for</strong> eachcomposite, after which composites<strong>and</strong> their nutrient profiles were usedto calculate expected nutrient levels in1,300- <strong>and</strong> 1,600-calorie diet patternsbased on the Food Guide Pyramid.The nutrient totals were then analyzedto determine whether children’s nutrientrequirements could be met by dietpatterns that con<strong>for</strong>m to Pyramid recommendations<strong>and</strong> that consist of thefoods most commonly eaten by children.18 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review

MethodsData SourcesData on 3-day food <strong>and</strong> nutrient intakesreported in the Continuing Survey ofFood Intakes by Individuals (CSFII)1989-91 <strong>for</strong> 1,053 children 2 to 6 yearsold were used in this study. This dataset was used because when work wasstarted, the data set offered the largestnumber of individuals <strong>and</strong> days <strong>for</strong>analysis. Sample weights were appliedto provide estimates that were representativeof the population. The datathat were used to calculate the nutrientprofiles of the composites <strong>for</strong> the foodgroups <strong>and</strong> subgroups came from theU.S. Department of Agriculture’s(USDA) Nutrient Data Base <strong>for</strong>Individual Intake Surveys, Release 7(1991).The Food Guide Servings Data Basewas used to report the amounts of foodconsumed as numbers of food guideservings. USDA’s <strong>Center</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong><strong>Policy</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Promotion</strong> (CNPP) developedthis data base by using the foodsreported in the CSFII 1989-91. TheFood Guide Servings Data Base consistsof food-item descriptions <strong>and</strong> thenumber of Pyramid servings per 100grams of food. Servings data are provided<strong>for</strong> the 5 major food groups <strong>and</strong>21 subgroups identified in the FoodGuide Pyramid.Most foods, including mixed dishes,were broken down into ingredient components,<strong>and</strong> their food group servingswere calculated <strong>for</strong> more than one foodgroup. When a food code’s typicalserving size, defined in the SurveyCode Book <strong>for</strong> CSFII 1989-91 <strong>and</strong>based generally on median servingsizes reported in USDA food consumptionsurveys, provided less than onefourthof a serving of a Pyramid foodgroup or subgroup, it was usually notcounted. For example, a serving ofoatmeal raisin cookies provided lessthan one-fourth of a Pyramid servingof raisins, so those raisins were notcounted toward fruit servings. Thesesmall amounts were not countedbecause one objective of the originalfood guidance system was ‘‘usability.’’It is unrealistic to expect Americans to‘‘count’’ small amounts of some foodstoward food group servings. However,if several ‘‘other vegetables’’ liketomatoes <strong>and</strong> onions were in smallamounts in a mixture, <strong>and</strong> these amountstogether added up to at least one-fourthserving, these ‘‘other vegetables’’ werecounted toward vegetable servings.ProceduresCNPP began the research process bybreaking down the foods that wereconsumed by children 2 to 6 years old,as reported in the CSFII 1989-91, intonumbers of food group <strong>and</strong> subgroupservings. The Food Guide ServingsData Base was used <strong>for</strong> this process.To identify specific food components,CNPP staff reviewed food codes thatcontributed food guide servings.All food items with similar foodcomponents were grouped in the sameitem-group. For example, broccoli soup<strong>and</strong> broccoli casserole both containedcooked broccoli <strong>and</strong> so were placedin the item-group <strong>for</strong> cooked broccoliwithin the subgroup <strong>for</strong> dark-greenvegetables. A composite was thenconstructed by summing intakes fromall the item-groups within a food group,with each item-group being weightedby the numbers of servings reported<strong>for</strong> children 2 to 6 years old. Then thepercentage contributed by each itemgroupin the food group or subgroupwas calculated. The total number ofservings of cooked broccoli consumed,<strong>for</strong> example, was divided by the totalnumber of servings of dark-greenvegetables consumed. This calculationproduced the percentage of the composite<strong>for</strong> dark-green vegetables that wascooked broccoli. Any item-group totalingless than 1 percent of the compositewas combined with another item-group,based on the similarity in nutrientcomposition or its use in meals.A food code most representative of anitem-group was then selected to representeach food-item group in each ofthe composites. The nutrient values ofthese food codes were used to calculatethe nutrient profiles of the composites.In developing the original nutrientprofiles <strong>for</strong> the food groups <strong>and</strong> subgroups,researchers included foodswith the least amount of fat <strong>and</strong> withoutadded sugars; thus, the originalphilosophical goal of flexibility <strong>for</strong> thefood guide was met. The food guidewas used to show consumers how toobtain nutrients while allowing themflexibility to choose sources of fat <strong>and</strong>added sugars within the fat <strong>and</strong> calorielimits specified (9). In addition, theFood Guide Pyramid is an educationaltool to help put the Dietary Guidelinesinto practice (8).To minimize fat, added sugars, <strong>and</strong>sodium, CNPP staff used the <strong>for</strong>m ofthe food item that was lowest in thesecomponents. For example, the deepyellowvegetable subgroup containedthe item-group <strong>for</strong> sweet potatoes. Torepresent the latter in the composite,CNPP used the code <strong>for</strong> a baked sweetpotato without added fat----despite thefact that children usually eat c<strong>and</strong>iedsweet potatoes. For most vegetable <strong>and</strong>cooked-grain item-groups, CNPP usedfood codes that specified ‘‘no saltadded in preparation.’’ In a few cases,CNPP used the salted <strong>for</strong>m to representpopular vegetables that are canned.Estimates of the percentage selected1999 Vol. 12 Nos. 3&4 19

. . . young children atesomewhat differenttypes <strong>and</strong> amountsof food items withineach food group <strong>and</strong>subgroup than didthe total population.in canned <strong>for</strong>m were calculated fromdata of the food supply (4).Non-<strong>for</strong>tified ready-to-eat <strong>and</strong> cookedbreakfast cereals were used in boththe composites <strong>for</strong> whole grains <strong>and</strong>enriched grains. Hence nutrient profilesof the composites do not overestimatethe nutrients <strong>for</strong> children who do noteat <strong>for</strong>tified breakfast cereals. Nutrientsadded at st<strong>and</strong>ard enrichment levels,as in enriched bread, were included inthe nutrient profiles <strong>for</strong> the composites.Folate <strong>for</strong>tification was not m<strong>and</strong>atedby the Government at the time theCSFII 1989-91 was conducted, so itwas not reflected in any of the nutrientprofiles <strong>for</strong> grain products.Once CNPP chose the food code torepresent each item-group, we calculatedgrams of the food code <strong>and</strong> correspondingnutrient values <strong>for</strong> its portionof the composite serving. Nutrient valueswere then summed across all items inthe food group or subgroup to determinethe composite’s nutrient profileper serving.Composites were not developed <strong>for</strong> themeat alternates (eggs, nuts <strong>and</strong> seeds)or <strong>for</strong> the milk, yogurt, <strong>and</strong> cheesegroup. The nutrient profiles of a foodgroup or subgroup reflect proportionatelythe nutrient content of the foodswithin them; consequently, the nutrientprofile of a food group or subgroupmost reflects the nutrient content ofthe most frequently consumed foodswithin that group.Nutrient profiles <strong>for</strong> the meat alternateswere represented by the nutrients inone large boiled egg <strong>and</strong> 2 tablespoonsof peanut butter, each of which countsas 1 ounce from the meat, poultry, fishgroup. Peanut butter was 90 percent ofyoung children’s servings of nuts <strong>and</strong>seeds in the CSFII 1989-91; thus, peanutbutter’s nutrient profile was used insteadof calculating a composite of allthe different nuts <strong>and</strong> seeds that wereconsumed in small quantities by youngchildren.All legumes were counted as vegetablesin the earlier research on Pyramid foodpatterns (1) <strong>and</strong> so were counted similarlyin this research project. One-halfcup of cooked legumes may be countedas 1 ounce of meat, poultry, or fishrather than 1 serving of vegetables.The nutrient profile <strong>for</strong> the milk, yogurt,<strong>and</strong> cheese group was represented by1 cup of nonfat milk, except <strong>for</strong> vitaminA. The amount of vitamin A used wasthe 76 RE per cup found in whole milk,instead of the 149 RE per cup foundin <strong>for</strong>tified nonfat milk. Thus overestimationof vitamin A was avoided<strong>for</strong> those who consumed non-<strong>for</strong>tifiedwhole milk products.The data on food intake, which wereused to develop the composites, wereexamined to identify the most popularfoods (at the food code level) <strong>and</strong>preparation styles in each item-group.Amounts reported eaten were alsoanalyzed. For each item-group, theaverage number of servings per reportwas calculated. This was the averagequantity of a specified food that waseaten by consumers during an eatingoccasion (at a single time). Then, theaverage number of servings per reportwas calculated <strong>for</strong> each food group orsubgroup.The food-group composites <strong>and</strong> nutrientprofiles <strong>for</strong> young children were comparedwith another set of compositesthat were developed <strong>for</strong> all individualsages 2 years <strong>and</strong> older who provided3 days of data in the CSFII 1989-91(N=11,488).20 <strong>Fam</strong><strong>ily</strong> <strong>Eco</strong><strong>nom</strong><strong>ics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Nutrition</strong> Review