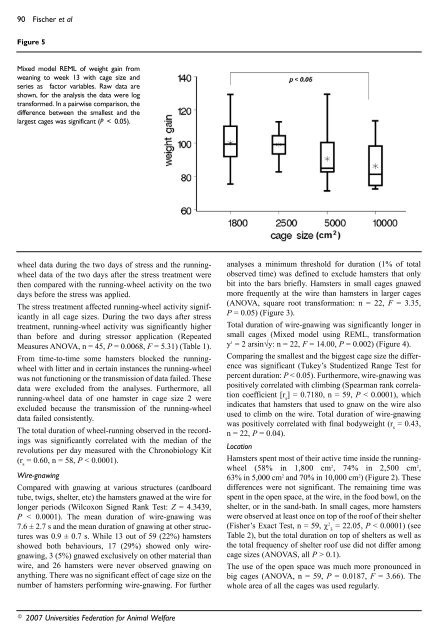

90 Fischer et alFigure 5Mixed model REML <strong>of</strong> weight ga<strong>in</strong> fromwean<strong>in</strong>g to week 13 with cage size andseries as factor variables. Raw data areshown, for the analysis the data were logtransformed. In a pairwise comparison, thedifference between the smallest and thelargest cages was significant (P < 0.05).wheel data dur<strong>in</strong>g the two days <strong>of</strong> stress and the runn<strong>in</strong>gwheeldata <strong>of</strong> the two days after the stress treatment werethen compared with the runn<strong>in</strong>g-wheel activity on the twodays before the stress was applied.The stress treatment affected runn<strong>in</strong>g-wheel activity significantly<strong>in</strong> all cage sizes. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the two days after stresstreatment, runn<strong>in</strong>g-wheel activity was significantly higherthan before and dur<strong>in</strong>g stressor application (RepeatedMeasures ANOVA, n = 45, P = 0.0068, F = 5.31) (Table 1).From time-to-time some <strong>hamsters</strong> blocked the runn<strong>in</strong>gwheelwith litter and <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>stances the runn<strong>in</strong>g-wheelwas not function<strong>in</strong>g or the transmission <strong>of</strong> data failed. Thesedata were excluded from the analyses. Furthermore, allrunn<strong>in</strong>g-wheel data <strong>of</strong> one hamster <strong>in</strong> cage size 2 wereexcluded because the transmission <strong>of</strong> the runn<strong>in</strong>g-wheeldata failed consistently.The total duration <strong>of</strong> wheel-runn<strong>in</strong>g observed <strong>in</strong> the record<strong>in</strong>gswas significantly correlated with the median <strong>of</strong> therevolutions per day measured with the Chronobiology Kit(r s= 0.60, n = 58, P < 0.0001).Wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>gCompared with gnaw<strong>in</strong>g at various structures (cardboardtube, twigs, shelter, etc) the <strong>hamsters</strong> gnawed at the wire forlonger periods (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test: Z = 4.3439,P < 0.0001). The mean duration <strong>of</strong> wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g was7.6 ± 2.7 s and the mean duration <strong>of</strong> gnaw<strong>in</strong>g at other structureswas 0.9 ± 0.7 s. While 13 out <strong>of</strong> 59 (22%) <strong>hamsters</strong>showed both behaviours, 17 (29%) showed only wiregnaw<strong>in</strong>g,3 (5%) gnawed exclusively on other material thanwire, and 26 <strong>hamsters</strong> were never observed gnaw<strong>in</strong>g onanyth<strong>in</strong>g. There was no significant effect <strong>of</strong> cage size on thenumber <strong>of</strong> <strong>hamsters</strong> perform<strong>in</strong>g wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g. For furtheranalyses a m<strong>in</strong>imum threshold for duration (1% <strong>of</strong> totalobserved time) was def<strong>in</strong>ed to exclude <strong>hamsters</strong> that onlybit <strong>in</strong>to the bars briefly. Hamsters <strong>in</strong> small cages gnawedmore frequently at the wire than <strong>hamsters</strong> <strong>in</strong> larger cages(ANOVA, square root transformation: n = 22, F = 3.35,P = 0.05) (Figure 3).Total duration <strong>of</strong> wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g was significantly longer <strong>in</strong>small cages (Mixed model us<strong>in</strong>g REML, transformationy 1 = 2 ars<strong>in</strong>√y: n = 22, F = 14.00, P = 0.002) (Figure 4).Compar<strong>in</strong>g the smallest and the biggest cage size the differencewas significant (Tukey’s Studentized Range Test forpercent duration: P < 0.05). Furthermore, wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g waspositively correlated with climb<strong>in</strong>g (Spearman rank correlationcoefficient [r s] = 0.7180, n = 59, P < 0.0001), which<strong>in</strong>dicates that <strong>hamsters</strong> that used to gnaw on the wire alsoused to climb on the wire. Total duration <strong>of</strong> wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>gwas positively correlated with f<strong>in</strong>al bodyweight (r s= 0.43,n = 22, P = 0.04).LocationHamsters spent most <strong>of</strong> their active time <strong>in</strong>side the runn<strong>in</strong>gwheel(58% <strong>in</strong> 1,800 cm 2 , 74% <strong>in</strong> 2,500 cm 2 ,63% <strong>in</strong> 5,000 cm 2 and 70% <strong>in</strong> 10,000 cm 2 ) (Figure 2). Thesedifferences were not significant. The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g time wasspent <strong>in</strong> the open space, at the wire, <strong>in</strong> the food bowl, on theshelter, or <strong>in</strong> the sand-bath. In small cages, more <strong>hamsters</strong>were observed at least once on top <strong>of</strong> the ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> their shelter(Fisher’s Exact Test, n = 59, χ 2 = 22.05, P < 0.0001) (see3Table 2), but the total duration on top <strong>of</strong> shelters as well asthe total frequency <strong>of</strong> shelter ro<strong>of</strong> use did not differ amongcage sizes (ANOVAS, all P > 0.1).The use <strong>of</strong> the open space was much more pronounced <strong>in</strong>big cages (ANOVA, n = 59, P = 0.0187, F = 3.66). Thewhole area <strong>of</strong> all the cages was used regularly.© 2007 Universities Federation for Animal Welfare

Cage size for <strong>hamsters</strong> 91BodyweightAt week 0 bodyweights did not differ significantly <strong>in</strong> all<strong>four</strong> cage sizes (ANOVA, log-transformation: n = 60,F = 2.65, P = 0.14). Weight ga<strong>in</strong> from wean<strong>in</strong>g untilweek 13 was significantly reduced <strong>in</strong> big cages (Mixedmodel on log-transformed weight ga<strong>in</strong>s: n = 57, P = 0.01,F 3, 32= 4.53) (Figure 5). Series, age at wean<strong>in</strong>g, and littersize had no effect on weight ga<strong>in</strong>. Body condition also didnot differ significantly between cage sizes (ANOVA:n = 57, F = 1.93, P = 0.14). Dur<strong>in</strong>g autopsy, no difference<strong>in</strong> the amount <strong>of</strong> fatty tissue was noticed.Stress hormones and organ weightsNeither plasma stress hormone levels nor the coefficient <strong>of</strong>cortisol/corticosterone differed between cage sizes (P > 0.1)(Table 3). No differences were found <strong>in</strong> organ weights<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the weights <strong>of</strong> the adrenal glands (Table 4).DiscussionThe aim <strong>of</strong> this study was to analyse behavioural differences<strong>of</strong> <strong>golden</strong> <strong>hamsters</strong> housed <strong>in</strong> different sized cages andsubjected to mild husbandry rout<strong>in</strong>e stressors and to drawconclusions about their welfare. Size related differences <strong>in</strong>wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g, use <strong>of</strong> the ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> their shelter as additionalspace, use <strong>of</strong> open space, and weight ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicated reducedwelfare <strong>in</strong> small cages. Our <strong>in</strong>vestigations showed that,although <strong>hamsters</strong> displayed wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> all cage sizes,<strong>hamsters</strong> <strong>in</strong> small cages performed wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g more<strong>of</strong>ten and for longer periods. In small cages, more <strong>hamsters</strong>made use <strong>of</strong> the ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> their shelter which could <strong>in</strong>dicatethat additional space was <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g welfare. The use <strong>of</strong>open space was much more pronounced <strong>in</strong> larger cages andthe whole area <strong>of</strong> the larger cages was used regularly. Thecage size did not <strong>in</strong>fluence runn<strong>in</strong>g-wheel activity <strong>of</strong><strong>hamsters</strong>. This was expected because rodents value wheelrunn<strong>in</strong>gvery much as shown <strong>in</strong> an operant test with mice(Sherw<strong>in</strong> 1998b).Hamsters gnawed longer and more frequently on the wirethan on other objects <strong>in</strong> their cage. Gnaw<strong>in</strong>g on cardboardtubes, twigs or the wooden shelter serves several purposes,such as help<strong>in</strong>g abrasion and clean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the teeth and alsoto produce nest<strong>in</strong>g material, provide food fibre, etc (Fischerpersonal observation 2004). Some <strong>hamsters</strong> shredded thecardboard tube and used its pieces as nest<strong>in</strong>g material. Incontrast, wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g seemed to be <strong>in</strong>effective; it couldnot be prevented by provid<strong>in</strong>g natural material to chew on,so wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g and gnaw<strong>in</strong>g at objects presumably have adifferent cause and/or function. Wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g might be anattempt to escape from the cage (Nevison et al 1999,Würbel et al 1998a, b), but it can also be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as redirectedbehaviour at a replacement object and thus as anabnormal behaviour, or even as a stereotypy. Stereotypicbehaviour is commonly def<strong>in</strong>ed as repetitive, unvary<strong>in</strong>gbehavioural patterns without obvious goal or function(Ödberg 1987), <strong>in</strong> animals <strong>kept</strong> under barren hous<strong>in</strong>g conditions(Mason 1991). Stereotypies are <strong>of</strong>ten observed <strong>in</strong>captive rodents (Würbel & Stauffacher 1996, 1997, 1998;Wiedenmayer 1997; Waibl<strong>in</strong>ger 1999) and are common<strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>of</strong> poor welfare (eg review by Mason 1991;Würbel 2001). Wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>hamsters</strong> <strong>in</strong> the presentstudy was repetitive, <strong>in</strong>variant, performed at a particularspot on the wire top <strong>of</strong> the cage (Würbel et al 1996), andwithout function. Even if this behaviour is not considered astereotypy but an attempt to escape from the cage, it is stillan <strong>in</strong>dication that the wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>hamsters</strong> were notcontent with their hous<strong>in</strong>g.Therefore, the results <strong>of</strong> this study <strong>in</strong>dicated that hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>big cages improved the welfare <strong>of</strong> the <strong>hamsters</strong> because itresulted <strong>in</strong> less wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g. The biggest cage, with a size<strong>of</strong> 10,000 cm 2 , was the one with the shortest duration <strong>of</strong>wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g as well as the lowest frequency. Duration andfrequency <strong>of</strong> wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 10,000 cm 2 was half <strong>of</strong> thatseen <strong>in</strong> 5,000 cm 2 cages, albeit non-significantly. However,even though <strong>hamsters</strong> <strong>in</strong> small cages performed more wiregnaw<strong>in</strong>gthan <strong>hamsters</strong> housed <strong>in</strong> bigger cages, wiregnaw<strong>in</strong>goccurred <strong>in</strong> all cages. This suggests that even acage <strong>of</strong> 10,000 cm 2 was too small for female <strong>golden</strong><strong>hamsters</strong>. If we estimate the natural territory size from them<strong>in</strong>imum distance between occupied burrows <strong>in</strong> Syria, ourbiggest cages represented a mere 0.007% <strong>of</strong> it.The positive correlation between wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g andclimb<strong>in</strong>g can be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by the preference <strong>of</strong> some<strong>hamsters</strong> to climb to a particular spot on the front or the top<strong>of</strong> the cage to gnaw on the wire. Some <strong>hamsters</strong> used toclimb while paus<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g. They usuallyclimbed up and down the front side <strong>of</strong> the wire top but thenreturned to the same po<strong>in</strong>t and restarted wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g.Climb<strong>in</strong>g was considered as the source behaviour pattern<strong>of</strong> stereotypic wire-gnaw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> laboratory mice (Würbelet al 1996).In addition to behavioural observations, physiologicalparameters could be useful to assess the welfare <strong>of</strong> the<strong>golden</strong> <strong>hamsters</strong>. The health <strong>of</strong> the animals is an importantfactor for welfare. Obesity and its negative consequencesare common <strong>in</strong> pets. Therefore it is important to give<strong>hamsters</strong> the appropriate cage size, where the risk <strong>of</strong> obesityis m<strong>in</strong>imised. Possible reasons for the higher weight ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>small cages could be lower energy expenditure and/orgreater food <strong>in</strong>take. Faster runn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> big cages, which usesmore energy, would expla<strong>in</strong> the higher energy consumption.Hamsters <strong>in</strong> smaller cages ga<strong>in</strong>ed more weight and wereobviously able to spend more energy on growth. At anadvanced age excessive energy will not be used for growth,at which po<strong>in</strong>t adiposis could become a problem <strong>in</strong> smallcages. The lack <strong>of</strong> a runn<strong>in</strong>g-wheel or other activities withthe possibility for high energy expenditure, could further<strong>in</strong>crease adiposis. Therefore, cage sizes 1 and 2 seem tohave been too small for the hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> pet <strong>hamsters</strong>.The lack <strong>of</strong> significant differences <strong>in</strong> hormonal levels couldbe due to methodological problems (Gebhardt-Henrich et alsubmitted). Due to the sensitivity <strong>of</strong> hormonal measurementsto (sometimes unknown and unavoidable) environmentalfactors, <strong>in</strong>terpretations <strong>of</strong> the stress levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>golden</strong><strong>hamsters</strong> based on these hormones must be made withcaution. It is probable that several problems contribute toAnimal Welfare 2007, 16: 85-93