Part Two, by Jim Kimbrough - Mushroom, the Journal of Wild ...

Part Two, by Jim Kimbrough - Mushroom, the Journal of Wild ...

Part Two, by Jim Kimbrough - Mushroom, the Journal of Wild ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

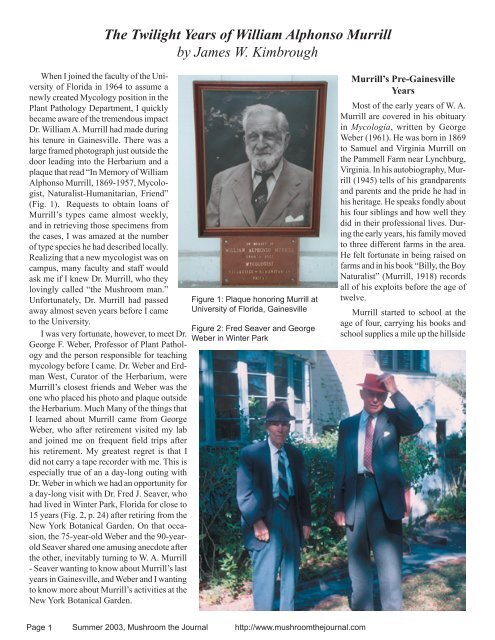

The Twilight Years <strong>of</strong> William Alphonso Murrill<strong>by</strong> James W. <strong>Kimbrough</strong>When I joined <strong>the</strong> faculty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University<strong>of</strong> Florida in 1964 to assume anewly created Mycology position in <strong>the</strong>Plant Pathology Department, I quicklybecame aware <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tremendous impactDr. William A. Murrill had made duringhis tenure in Gainesville. There was alarge framed photograph just outside <strong>the</strong>door leading into <strong>the</strong> Herbarium and aplaque that read “In Memory <strong>of</strong> WilliamAlphonso Murrill, 1869-1957, Mycologist,Naturalist-Humanitarian, Friend”(Fig. 1). Requests to obtain loans <strong>of</strong>Murrill’s types came almost weekly,and in retrieving those specimens from<strong>the</strong> cases, I was amazed at <strong>the</strong> number<strong>of</strong> type species he had described locally.Realizing that a new mycologist was oncampus, many faculty and staff wouldask me if I knew Dr. Murrill, who <strong>the</strong>ylovingly called “<strong>the</strong> <strong>Mushroom</strong> man.”Unfortunately, Dr. Murrill had passedaway almost seven years before I cameto <strong>the</strong> University.I was very fortunate, however, to meet Dr.George F. Weber, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Plant Pathologyand <strong>the</strong> person responsible for teachingmycology before I came. Dr. Weber and ErdmanWest, Curator <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Herbarium, wereMurrill’s closest friends and Weber was <strong>the</strong>one who placed his photo and plaque outside<strong>the</strong> Herbarium. Much Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> things thatI learned about Murrill came from GeorgeWeber, who after retirement visited my laband joined me on frequent field trips afterhis retirement. My greatest regret is that Idid not carry a tape recorder with me. This isespecially true <strong>of</strong> an a day-long outing withDr. Weber in which we had an opportunity fora day-long visit with Dr. Fred J. Seaver, whohad lived in Winter Park, Florida for close to15 years (Fig. 2, p. 24) after retiring from <strong>the</strong>New York Botanical Garden. On that occasion,<strong>the</strong> 75-year-old Weber and <strong>the</strong> 90-yearoldSeaver shared one amusing anecdote after<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, inevitably turning to W. A. Murrill- Seaver wanting to know about Murrill’s lastyears in Gainesville, and Weber and I wantingto know more about Murrill’s activities at <strong>the</strong>New York Botanical Garden.Figure 1: Plaque honoring Murrill atUniversity <strong>of</strong> Florida, GainesvilleFigure 2: Fred Seaver and GeorgeWeber in Winter ParkMurrill’s Pre-GainesvilleYearsMost <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> early years <strong>of</strong> W. A.Murrill are covered in his obituaryin Mycologia, written <strong>by</strong> GeorgeWeber (1961). He was born in 1869to Samuel and Virginia Murrill on<strong>the</strong> Pammell Farm near Lynchburg,Virginia. In his autobiography, Murrill(1945) tells <strong>of</strong> his grandparentsand parents and <strong>the</strong> pride he had inhis heritage. He speaks fondly abouthis four siblings and how well <strong>the</strong>ydid in <strong>the</strong>ir pr<strong>of</strong>essional lives. During<strong>the</strong> early years, his family movedto three different farms in <strong>the</strong> area.He felt fortunate in being raised onfarms and in his book “Billy, <strong>the</strong> BoyNaturalist” (Murrill, 1918) recordsall <strong>of</strong> his exploits before <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong>twelve.Murrill started to school at <strong>the</strong>age <strong>of</strong> four, carrying his books andschool supplies a mile up <strong>the</strong> hillsidePage Summer 2003, <strong>Mushroom</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> http://www.mushroom<strong>the</strong>journal.com1

Figure 3: Murrill at Stauntonto <strong>the</strong> school. Most <strong>of</strong> his early schoolingwas in Blacksburg, where his familymoved to <strong>the</strong> Miller farm just south <strong>of</strong>town. He first took piano lessons at <strong>the</strong>age <strong>of</strong> nine and his mo<strong>the</strong>r encouragedhim in <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> fine arts. He laterbecame an outstanding pianist, artist,writer, and was highly creative in anumber <strong>of</strong> fields. At <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> twelve,he completed high school and becamea student at <strong>the</strong> Virginia Agriculturaland Mechanical College in Blacksburg.He received his BS with highest honors<strong>the</strong>re in 1887, at <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> sixteen. Thefollowing autumn, he took charge <strong>of</strong> asmall country school near Blacksburg.Murrill (1944) recounts his mo<strong>the</strong>r havinghigh ambitions for him, and when anopportunity came for him to be able togo to Randolph-Macon College in Ashland,Virginia, she urged him to take advantage<strong>of</strong> it. He received a second BSdegree at Randolph-Macon in 1889, followedsoon <strong>by</strong> a Master’s <strong>of</strong> Art in 1891.At this stage, Murrill pondered what washe going to do first. That was soon answered when he receivedand accepted an <strong>of</strong>fer <strong>of</strong> a teaching position at Bowling GreenFemale Seminar where he taught for two years.In 1893, Murrill joined <strong>the</strong> Wesleyan Female Institute inStaunton, Virginia, where he spent four enjoyable years (Fig.3). There, he was involved with curriculum planning and in studentrecruitment, which carried him to Missouri and Arkansas,seeking top-flight candidates. With opportunities to see beyond<strong>the</strong> south-central regions <strong>of</strong> Virginia, Murrill became increasinginterested in field biology. By this time, he was consistentlyreferring to himself as “<strong>the</strong> Naturalist.” He frequently visited<strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Virginia and attended lectures <strong>of</strong> prominentchemists, zoologists, and geologists; even being <strong>of</strong> assistancein <strong>the</strong> anatomy labs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> medical center. Trips to Washingtonand visits to <strong>the</strong> National Museum peaked his interest in naturalsciences. During his tenure at Staunton, he became convincedthat he wanted to specialize in biological sciences and do graduatework.During his second year at Wesleyan, Murrill began to thinkseriously about graduate school and had initially decided to goto John Hopkins and study Zoology, Botany, and Chemistry. Afamily friend, Dr. Gildersleeve, secured a fellowship for him,and in his final years at Wesleyan he prepared himself for studiesat John Hopkins. On a trip to Washington, however, a couple <strong>of</strong>friends, both Cornell graduates, suggested to him that job opportunitieswould be far greater in Botany and suggested that hedo his graduate studies at Cornell. Murrill made his decision toattend Cornell and stated in later years that he never regretted it. In <strong>the</strong> summer <strong>of</strong>1897 he actively collected and prepared specimens <strong>of</strong> parasitic fungi to bring andaccession in <strong>the</strong> Cornell Herbarium. He was given a fellowship in Botany whereFigure 4: Murrill starting out at <strong>the</strong> New York Botanical Gardens1Also known as Diapor<strong>the</strong> parasitica, Cryphonectria parasitica, and probablya couple <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r names, too. - LSPage Summer 2003, <strong>Mushroom</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> http://www.mushroom<strong>the</strong>journal.com2

(continued from p. 23)he worked with Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Atkinson. InSeptember 1897 he married Edna LeeLuttrell and, as Weber recounts, <strong>the</strong>ironly child, a son born in 1899, died ininfancy. In his autobiography, MurrillFigure 5: Murrill standing on deadchestnut treedoes not mention marriage or <strong>the</strong> son,and does not say anything about hisfamily while at Cornell. In his secondand third year at Cornell, he lived inCascadilla Hall, a male dormitory that Ilived in for one term 51 years later!Figure 6: Murrill examining a tree atKew Botanical GardensWhen Benjamin Minge Duggar retiredfrom Cornell in 1898, Murrill wasgiven <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> Assistant CryptogamicBotanist which he held until 1900,<strong>the</strong> year he received his PhD. After a tripto Paris to attend <strong>the</strong> International BotanicalCongress and a brief time <strong>of</strong> jobhunting,he contacted a Virginia friendwho <strong>of</strong>fered him a job teaching biologyat DeWitt Clinton High School in NewYork. In subsequent years, he spent hissummers traveling to museums abroadand collaborating with pr<strong>of</strong>essors atColumbia University, close to where helived. With his increased involvement in<strong>the</strong> Torrey Botanical Club and growingpopularity as a great speaker at home andabroad, Murrill was in a perfect positionto be selected as Asssistant Curator at<strong>the</strong> New York Botanical Garden whenFranklin Sumner Earle was appointedDirector <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Experiment Station inCuba (Fig. 4).Murrill enjoyed 20 highly productiveyears at <strong>the</strong> New York Botanical Garden.He enjoyed <strong>the</strong> hustle and bustle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>big city with its museums, <strong>the</strong>aters,music halls, zoos, and baseball parks.Although he had established himself asan international authority <strong>of</strong> mushroomsand bracket fungi, about this time a devastatingdisease <strong>of</strong> chestnuts appearedand he immediately set out to find <strong>the</strong>cause and cure. Within a year, he discoveredthat <strong>the</strong> dieback was caused <strong>by</strong> Endothiaparasitica, 1 much to <strong>the</strong> chagrin<strong>of</strong> a group <strong>of</strong> USDA mycologists whohad been unsuccessful in determining<strong>the</strong> cause (Fig. 5). The cure for chestnutblight is still being investigated.Murrill traveled extensively andwas in great demand as a speaker on alarge variety <strong>of</strong> subjects. He visited all<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> major museums throughout <strong>of</strong>Europe and made a number <strong>of</strong> expeditionsto <strong>the</strong> Caribbean, Mexico, Braziland places between. Unfortunately, allwas not rosy for him in New York. Heand Nathaniel Lord Britton, Director <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Garden, became at odds over rules<strong>of</strong> nomenclature and slowly but surely<strong>the</strong>ir relationship deteriorated. On hisreturn several months late from a Europeanexcursion, Murrill found himselfdemoted to a position <strong>of</strong> Supervisor <strong>of</strong>Public Instruction with a very low salary.Fred Seaver, one <strong>of</strong> Murrill’s co-workersat <strong>the</strong> Garden, shared that a polycystickidney problem hospitalized him in aFig. 7: Murrill building his log cabin inVirginiasmall French town where he almost diedand had no way to contact his wife orcolleagues at <strong>the</strong> Garden. Murrill’s wifetraveled with him all throughout <strong>the</strong> US,but absolutely refused to accompanyhim abroad, having a deadly fear <strong>of</strong>water. With his extensive travel abroad,his wife spent an inordinate amount <strong>of</strong>time alone.Weber (1961) states, “His busy existencebecame clouded <strong>by</strong> a series <strong>of</strong>circumstances that culminated in <strong>the</strong> tendering<strong>of</strong> his resignation to <strong>the</strong> Directorin-Chief<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Garden in August, 1924,ending his public career that possessedevery indication <strong>of</strong> abundant accomplishments.Dr. Murrill changed fromone plagued with <strong>the</strong> worry and responsibilities<strong>of</strong> a complicated society in highplaces to one devoting all his thoughtsto his own individual self.” Accordingto Weber, Murrill was hospitalized intermittentlyfor over a year for nervousinstabilities and physical exhaustion. Hiswife left his home and shortly <strong>the</strong>reafterserved him with a divorce decree. Asfinancial problems developed, he becamea haunted man. Mentally troubled,alone, and discouraged, he left <strong>the</strong> Gardenand went to live with an aunt nearhis birthplace near Lynchburg, Virginia.The Naturalist soon associated himselfwith trees, flowers, birds, and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rwildlife in mountains close <strong>by</strong>, and soonbecame busy building a log cabin <strong>the</strong>re(Fig. 7).Page Summer 2003, <strong>Mushroom</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> http://www.mushroom<strong>the</strong>journal.com3

Figure 8: The “Tin Can Tourist Camp” where Murrill initially stayed in FloridaBefore his resignation from <strong>the</strong> Garden,Murrill had made collecting tripsto Florida as late as 1923. After a yearin Virginia, as his mental and physicalhealth improved, he again made his wayto Gainesville, and for <strong>the</strong> next couple<strong>of</strong> years he made regular trips from Virginia.It was during one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se visitsthat Dr. Weber and his wife Kate discoveredthis “tall, robust, dignified, pleasantstranger providing a piano concert for<strong>the</strong> transient tourists at <strong>the</strong>ir recreationhall in <strong>the</strong> local tourist court.” Weberrecalled that he immediately recognized<strong>the</strong> gentleman as Dr. Murrill.Murrill’s Twilight Years in FloridaWeber was unsure as to how Murrillarrived in Gainesville or how long hehad been living in <strong>the</strong> tourist court where<strong>the</strong>y first spotted him. Dr. Weber, notingthat Murrill looked unkempt, frail, andhaggard, more or less took him underhis wing and, along with Pr<strong>of</strong>. West,saw that he was properly dressed andfed. Murrill spent his final 32 years inGainesville, built a small home andrental cottages here, and went to <strong>the</strong>University <strong>of</strong> Florida daily to visitGeorge Weber and Erdman West.While visiting <strong>the</strong> Florida Museumin <strong>the</strong> old capital building in Tallahasseerecently, I saw a large photo <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> TinCan Tourist Camp in Gainesville takenin <strong>the</strong> early 30s (Fig.8). This discoverystirred my curiosity: could this be whereMurrill stayed? I think so. Among itemsin <strong>the</strong> Alachua County Library DistrictHeritage Collection 2002, <strong>the</strong>re is afeature on <strong>the</strong> Tin Can Tourist Camp. Itstates, “Today’s travelers move on superhighwaysand stay in modern motels;<strong>the</strong>y also have <strong>the</strong> choice <strong>of</strong> travelingFigure 9: Murrill's first house in Gainesvillewith campers and recreational vehiclesthat <strong>of</strong>fer many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> comforts<strong>of</strong> home. But in <strong>the</strong> 1920s after WorldWar I, when many folks began movingto Florida, moving meant bravinguncertain lodging. Tin Can tourism(using <strong>the</strong> car and a tent for lodging)was a common solution. One camp,aptly named “Tin Can Tourist Camp,”was located in Gainesville, located at<strong>the</strong> present-day site <strong>of</strong> Shands AlachuaGeneral Hospital.”Since Murrill did not drive, it ishighly likely that he traveled withfriends from Virginia to Florida,stopping at various Tin Cup TouristCamps throughout <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>ast.Interestingly, <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tin CupTourist Court was only a few blocksfrom where Weber and his wife Katelived. Weber shared with me that<strong>the</strong> two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m went to <strong>the</strong> touristcourt frequently to purchase jams, jellies,fruits, and vegetables that farmersfrom <strong>the</strong> countryside would bring to sellto <strong>the</strong> travelers. It was not known untilrecently how long Murrill lived in <strong>the</strong>tourist camp. Correspondence betweenMurrill and John Kunkel Small (ano<strong>the</strong>rcolleague from <strong>the</strong> NY Botanical Garden)reveals that Murrill wrote to Smallon March 9, 1927, commenting that hewas still at <strong>the</strong> Tourist Camp but he wasstarting to build a studio to use as astoreroom while he worked on his maindwelling (Fig. 9). We know that MurrillPage Summer 2003, <strong>Mushroom</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> http://www.mushroom<strong>the</strong>journal.com4

Figure 10: The second house that Murrill builtwas very interested in <strong>the</strong> plants aroundnorth central Florida and correspondedfrequently with Small, who was workingon A Manual <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>astern Flora.<strong>Two</strong> post cards dated 1926 written <strong>by</strong>Small were addressed to W. A. Murrill,Tourist Court, Gainesville, Florida, oneindicating that he had visited Murrill inFlorida recently. In Murrill’s 1927 letterto Small, he states “I am at <strong>the</strong> TouristCamp in a cottage, when you came lastI was <strong>of</strong>f on a watersnake hunt.” Verylikely, Murrill came to <strong>the</strong> tourist campin Gainesville in <strong>the</strong> winter <strong>of</strong> 1925.<strong>Two</strong> different stories emerge whenyou compare Murrill’s account <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> early days in Gainesville to whatWeber recollects. Murrill states in hisautobiography that for a few years afterhe had built his cabin near Lynchburg,“he followed <strong>the</strong> birds to <strong>the</strong> south andwandered about from one lovely spot toano<strong>the</strong>r until returning spring beckonedhim northward again.... The final stagecame when <strong>the</strong> study <strong>of</strong> mosquitoes andspiders required him to spend <strong>the</strong> firstsummer in Gainesville. Only <strong>the</strong>n didhe come to realize <strong>the</strong> richness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>endemic biota, and especially <strong>the</strong> vastopportunity in <strong>the</strong> fleshy fungi, whichcaused him to return to this group almostexclusively in later years.” Webersays that Murrill had every intention <strong>of</strong>returning to Virginia in <strong>the</strong> summer aswas his practice, but he was hospitalizedin <strong>the</strong> University Infirmary with his recurringkidney problem. His stay in <strong>the</strong>infirmary lasted for several weeks andon his release <strong>the</strong> summer rains werehere. And so were <strong>the</strong> mushrooms, inabundance! Weber recalled that this was<strong>the</strong> first “spark <strong>of</strong> life” he had seen in<strong>the</strong> “old man’s eyes” during <strong>the</strong> monthsthat he had been in Gainesville. Murrillwas excited: this was <strong>the</strong> first time hehad seen <strong>the</strong> summer flushes <strong>of</strong> mushroomsin Florida. He needed collectingsupplies, a desk, and a microscope.Crowded for teaching, research, andherbarium space, <strong>the</strong>y provided himwith a desk, microscope, and lamp on<strong>the</strong> third floor stairway landing in RolfsHall, close to <strong>the</strong> Herbarium and to <strong>the</strong><strong>of</strong>fices <strong>of</strong> Weber and West.With a new “lease on life,” Murrillasked Weber if he would determine if hehad money at <strong>the</strong> New York BotanicalGarden from <strong>the</strong> sale <strong>of</strong> his book Edibleand Poisonous <strong>Mushroom</strong>s and <strong>the</strong>accompanying color chart, published<strong>by</strong> him in 1916. He quickly receiveda check for $600.00 and a stack <strong>of</strong>unsold books and charts. With thismoney he bought a small lot, sometools and building supplies, and builta small woodframe house at 203 NW9 th Terrace between <strong>the</strong> University anddowntown Gainesville (Fig. 9). Murrill(1945) states that “Having built one littlehouse in Gainesville, <strong>the</strong> Naturalist triedano<strong>the</strong>r and ano<strong>the</strong>r just for <strong>the</strong> fun <strong>of</strong>it.” Weber said that he built <strong>the</strong>m forrental property (Fig. 10).Although Murrill lived alone, hewas seldom alone. He spent most <strong>of</strong>his time on and around <strong>the</strong> campus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>University <strong>of</strong> Florida, where <strong>the</strong>re weremany tree species that supported all sorts<strong>of</strong> ectomycorrhizal mushrooms: severalflushes in <strong>the</strong> summer and o<strong>the</strong>r flushesduring mild winter months. He becamea fixture on campus with his basket andwalking cane, poking around shrubs andhedges for mushrooms. Students andfaculty were amazed with him and enjoyedjoining him on excursions aroundand near <strong>the</strong> campus. He was a greatstory-teller and he fascinated everyonewith his tales <strong>of</strong> travels to exotic places,entertaining royal families in variousEuropean countries, and his familiaritywith every plant or mushroom speciesaround. The nurses in <strong>the</strong> infirmaryFigure 11: Murrill (in front) with team<strong>of</strong> Florida botanists and fallen cypresstreeand secretaries around campus all “fellin love” with him and delighted with<strong>the</strong> opportunities to chat with him andlearn <strong>of</strong> his escapades. Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> PlantPathology and Forestry Faculty wouldtake him to <strong>the</strong> fields and forests aroundnorth central Florida. On rare occasionshe would be able to visit state parks in<strong>the</strong> lower peninsula <strong>of</strong> Florida. In August1938, he, Weber, West, R. K. Voorhees,and A. S. Rhoads discovered cypresstrees infected with Fomes geotropus,<strong>the</strong> fungus that was later determined<strong>by</strong> Murrill to be <strong>the</strong> cause <strong>of</strong> “peckycypress” (Fig. 11).During <strong>the</strong> late 30s and early 40s,Murrill shaved away his beard andPage Summer 2003, <strong>Mushroom</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> http://www.mushroom<strong>the</strong>journal.com5

mustache for a few years (Fig. 12). Helooked forlorn and unusual becausehe had been adorned with a mustachefrom graduate school days in Virginiaand with a distinct beard going back tohis tenure at Cornell. This was <strong>the</strong> beginning<strong>of</strong> a period when he started toactively describe and publish again on<strong>the</strong> new fungi he was finding. Murrill(1945) states “<strong>the</strong> gilded net had disappeared;routine work was no more, likea boat above <strong>the</strong> rapids on a quiet lakehe cruised on gentle waters withoutcompulsion or fear, devoting his attentionfreely and forcefully to things heloved.”Murrill had strange work habits, risingafter midmorning, getting his basketand collecting gear toge<strong>the</strong>r, and strikingout around campus or favorite woodlotsin <strong>the</strong> suburbs. Some <strong>of</strong> his favoritesites included <strong>the</strong> Devil’s Millhopper,SanFelasco Hammock, Sugarfoot Hammock,Planera Hammock, Kelly’s Hammock,Muck Pond, Paynes Praire, anda number <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs close <strong>by</strong> and withinwalking distance. He would return tohis desk on <strong>the</strong> Rolfs Hall landing andproceed to sort, identify, and preparehis collections for drying. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>specimen labels were hand-written andcarefully sorted. During <strong>the</strong> mushroomseason, he seldom returned to his homewhich was 12 or 15 blocks from campus.Instead, he would work late at his deskin Rolfs Hall and in <strong>the</strong> early morninghours cross <strong>the</strong> street and make his wayinto <strong>the</strong> lob<strong>by</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Student UnionBuilding. There he would find very s<strong>of</strong>t couches onwhich to sleep for <strong>the</strong> remainder <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> night. Asstudents came to <strong>the</strong> Union cafeteria for breakfast,<strong>the</strong>y would wake Murrill and invite him to breakfast,enjoying every moment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir meal with <strong>the</strong> oldgentleman. Weber recounted that seldom did Murrillever have to buy or make his breakfast.During <strong>the</strong> last fifteen years <strong>of</strong> his life, he hadno income beyond <strong>the</strong> revenue he received from hisrental houses and <strong>the</strong> sale <strong>of</strong> popular and scientificarticles that he published himself. Because <strong>of</strong> hissignificant contribution <strong>of</strong> specimens to <strong>the</strong> ExperimentStation Herbarium, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor West persuaded<strong>the</strong> administration to give him a $50.00 per monthhonorarium. In some <strong>of</strong> his last few years, he receivedFigure 12: Murrill in <strong>the</strong> late 1930ssome financial and medical support from<strong>the</strong> Florida Social Welfare Board. He becamevery actively involved with localgarden clubs, and organized a natureclub that made weekly forays to severalexcellent collecting areas (Weber1961). His work with <strong>the</strong> Girl Scouts, inwhich he was active while at <strong>the</strong> BotanicalGarden, was revived and continuedactive for many years in Gainesville.He wrote a number <strong>of</strong> popular bookletswhich were dedicated to <strong>the</strong> Boy Scoutsand Girl Scouts. In total, he published118 popular and scientific papers duringhis final years in Florida. Throughouthis career he collected more than 75,000Figure 13: Murrill at 86 years <strong>of</strong> agespecimens and described approximately1700 new species. More than 8,000specimens were collected in Florida, in<strong>of</strong> which more than 700 were describedas new species.Murrill published 20 books, 500 scientificarticles, and 800 popular articles.Many prominent agaricologists visitedand consulted with Murrill while hewas at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Florida. Theseincluded Rolf Singer, Lexemuel RayHesler, Gertrude Burlingham, JosiahLowe, Alexander H. Smith, and o<strong>the</strong>rs.The late Dr. Dan Roberts, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>Plant Pathology, told <strong>of</strong> times whenhe was a student in <strong>the</strong> 50s, that whenapproaching Rolfs Hall to do work in<strong>the</strong> evenings, he would hear <strong>the</strong> heateddebates between Singer and Murrillfrom blocks away. Dan recounts thatat times <strong>the</strong>ir arguments became sointense that he felt <strong>the</strong>y would come toblows. In 1954, <strong>the</strong> Mycological Society<strong>of</strong> America held its annual meeting at<strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Florida. Murrill waspresent in many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se sessions andespecially delighted in looking over andhelping with identification <strong>of</strong> specimenscollected during <strong>the</strong> MSA forays.Perhaps <strong>the</strong> last photograph wasmade <strong>of</strong> Dr. Murrill during <strong>the</strong> celebration<strong>of</strong> his 86 th birthday (Fig. 13)when <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Botany honoredhim with a birthday party attended<strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University, <strong>the</strong>Provost <strong>of</strong> Agriculture, <strong>the</strong> Director <strong>of</strong>Page Summer 2003, <strong>Mushroom</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> http://www.mushroom<strong>the</strong>journal.com6

<strong>the</strong> Experiment Station, and many <strong>of</strong> hisfriends.Murrill continued to describenew species up until his last publicationin 1955, a new species <strong>of</strong> Amanitafrom Florida (Mycologia 47:427).Little did he imagine that a small whitemushroom found in deep mulch aroundGainesville, which he named Amanitaneglecta, would be <strong>the</strong> last mushroomhe would describe. As Weber (1961)recounts, “During <strong>the</strong> last years his applicationsbecame less regular, althoughhis enthusiasm never diminished evenup to <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> his last illness. Even<strong>the</strong>n he reported <strong>of</strong> his own volition to<strong>the</strong> University Infirmary where he collapsedwhile <strong>the</strong> doctor was examininghim”. After a month’s hospitalization,he died in Alachua General Hospital inGainesville on Dec. 25, 1957. He wasburied in <strong>the</strong> Evergreen Cemetary at 401SE 21 st Avenue (Fig. 14). His gravesiteis near pines and sprawling live oaktrees that will provide an abundance<strong>of</strong> mushrooms and bracket fungi withwhich, perhaps, his spirit can minglethroughout eternity.As an international traveler, Murrillhad made personal friends will<strong>the</strong> most prominent mycologists in <strong>the</strong>major museums and o<strong>the</strong>r institutionsin Europe, South and Central America,and throughout <strong>the</strong> United States. Whilehe had cultivated friendships with manypeople in Gainesville, without doubt hisclosest friend was Pr<strong>of</strong>essor George F.Weber. George first spotted him at <strong>the</strong>tourist court, took him “under his wing,”helped him get established at <strong>the</strong> University,and was able to secure funds forhis survival. After Murrill’s death, Weberwould go to <strong>the</strong> cemetery every yeararound Christmas, <strong>the</strong> anniversary <strong>of</strong> hisdeath, to see that his gravesite was cleanFigure 15: George Weber tending Murrill's graveand to provide flowers (Fig. 15).Dr. William Alfonso Murrill choseto spend his retiring days in Gainesvilleand became an ever-present stimulus to<strong>the</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>geographical distribution and hostrange <strong>of</strong> its <strong>the</strong> fungi, particularly <strong>the</strong>Basidiomycetes. He not only was amaster mycologist but an ever patientteacher to whom many owed much in<strong>the</strong> way <strong>of</strong> confidence in him and his accomplishments.As Weber (1961) states,“so ended <strong>the</strong> life so richly endowedwith information, humility, sincerity,joyfulness, and kindness.”AcknowledgmentsI would like to thank Ms. Sally Bennyfor scanning <strong>the</strong> images and inserting<strong>the</strong>m into <strong>the</strong> manuscript, and Dr. GeraldBenny and Ms. Jennifer Gillett for helpingwith <strong>the</strong> illustrations and reviewing<strong>the</strong> manuscript.Literature citedMurrill, W. A. 1918. Billy <strong>the</strong> BoyNaturalist. Self-published, New YorkEra Printing Co., Lancaster, PA. 252pp.Murrill, W. A. 1945. Autobiography.Self-published, Gainesville, FL. 165pp.Murrill, W. A. 1955. “A new species<strong>of</strong> Amanita from Florida”, Mycologia47:427.Weber, George F. 1961. “WilliamAlphonso Murrill”, Mycologia 53:543-557.Figure 14: Murrill's gravestonePage Summer 2003, <strong>Mushroom</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> http://www.mushroom<strong>the</strong>journal.com7