A ustralia Pacific - Illegal Logging Portal

A ustralia Pacific - Illegal Logging Portal

A ustralia Pacific - Illegal Logging Portal

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

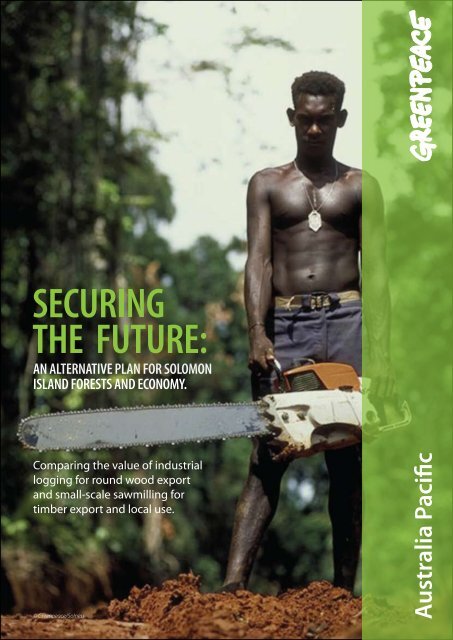

AN ALTERNATIVE PLAN FOR SOLOMONISLAND FORESTS AND ECONOMY.Comparing the value of industriallogging for round wood exportand small-scale sawmilling fortimber export and local use.© Greenpeace/SolnessA<strong>ustralia</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>

1. INTRODUCTION:7 September 2004. <strong>Logging</strong> on a riverbank in the Solomon Islands.Greenpeace is committed to seeking responsible and ecologicallysustainable alternatives to logging and supports ecoforestryprojects in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon islands.© GreenpeaceThe Solomon Islands has 2.8 million hectares offorests, covering around 85% of the total land area.However, only one fifth (600,000 ha) of the naturalforest area is suitable for commercial logging 1 , andall remaining large intact forest areas (>50,000ha)are now only found in the poorly accessible hill andmountain areas (see Map). The loggable forest hasbeen heavily exploited over the last two decadesand current logging is out of control.Industrial logging in Solomon Islands is dominatedby foreign companies who along with local frontcompanies and contractors, landowner agents andmiddlemen, and a compliant government,have been logging at a rate that is fourtimes the estimated ‘sustainable yield’, orthe level of non-declining harvest 2 .Further, many other reports andassessments have documented financialirregularities such as transfer pricing,misreporting and tax avoidance 3 ,serious environmental and social impacts 4 ,and how it is economically not asbeneficial to local landowners as smallscaleeconomic activity 5 .The logging sector currently accounts for 67%of export receipts, 15% of domestic governmentrevenue, and 15 % of GDP 6 . However the InternationalMonetary Fund (IMF) recently predicted a rapidcollapse of logging with commercial natural forestsbeing logged out by 2014 7 . The IMF, the Central Bankof the Solomon Islands and the Governor General ofSolomon Islands have warned of serious financial,economic and social impacts when this happens 8 . It isforecast that economic growth will decline to 1.5% perannum, down from 10% in 2007, largely due to a rapiddecline in logging as commercial forests are loggedout.This report gives some background on the loggingindustry and it’s impacts, and presents a financialanalysis that compares industrial logging for round logexports with community ecoforestry for sawn timberexports and domestic use. The analysis builds on workalready carried out by the A<strong>ustralia</strong>n Aid supportedNational Forest Resource Assessments 9 , the CentralBank of the Solomon Islands, and the IMF, with thekey new addition of financial data from the growingvillage-based small-scale sawmilling sector. Optionsfor a different forestry sector future for the SolomonIslands are presented along with estimated profit andNet Present Value (NPV) 10 . Recommendations aremade to the Solomon Islands Government and forestresource owners, and donor governmentsand institutions.Solomon Islands Forests4 Securing the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy

1.Children of the Lobi community, Marovo Lagoon, sit on a newly cuttree from the Greenpeace-supported ecoforestry project in their village.Ecoforestry is one way to protect forests for future generations.© Greenpeace/BehringSecuring the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy 5

2. OVERVIEW OF DESTRUCTIVEINDUSTRIAL LOGGINGIN SOLOMON ISLANDSIndustrial logging began accelerating in SolomonIslands from the 1980s when Asian (mainly Malaysianand Korean) companies began entering the sector andwhen there was a shift from logging on governmentland to customary owned land 11 . This post-colonialearly independence period, under the SolomonMamaloni-led government, moved relatively quicklytowards economic reliance on logs for export andgovernment revenue – 56% and 31% respectively by1994. It was during this period that the log harvestbegan to exceed ‘sustainable yield’ levels, increasingfrom 261,000 m3 in 1987 12 , to over 600,000 m3 in1997, to a predicted 1,400,000 m3 in 2008 – over 5times the sustainable rate 13 . During the ‘ethnic tension’period, from 1999 – 2003, logging unlike virtually allother commercial activities, continued to operateand expand 14 , highlighting the ability of this sector tothrive in a weak governance environment.During this period of unrestrained expansion therewere many attempts to bring logging under controland considerable amounts of information releasedon its economic, social and environmental impacts.A<strong>ustralia</strong>n aid funded monitoring and timber controlcapacity was installed several times over a 15-yearperiod 15 , and while the monitoring documented theproblem well (an unsustainable sustainable yield rateof harvest), and even recommended establishing largeconservation areas 16 , the industry was not broughtunder control.Sawn eco-timber being loaded into a container for export.Sawn eco-timber is 58% more profitable to landowners andgovernment than round logs for export. © Greenpeace/NeavesA<strong>ustralia</strong>’s response has been to recommend theestablishment of plantations as a way of building theforestry sector 17 , with these plantations convertinglogged over forest or old village garden sites. A<strong>ustralia</strong>has consistently ignored the potential for villagebasedportable sawmilling from natural forest such ascommunity ecoforestry.At least two Solomon Island governments (in 1994and 1997/98) have attempted to reform the loggingsector by cancelling licences 18 and imposing amoratorium on new licences. However, they wereshort lived with these governments being overturned,allegedly through bribes from logging companies 19 .Solomon Islands courts have also found loggingcompanies to be operating illegally 20 but this hasdone little to slow the onward march of the industryto systematically log all the commercial forests of thecountry. In some situations there has been resistancefrom landowners, and while recently this has haltedsome logging 21 , it has in the past been disastrousfor some communities such as the 1995 murder oflocal community leader Martin Apa who opposedthe logging of Pavuvu Island by Malaysian companyMaving Bros Ltd 22 .6 Securing the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy

<strong>Logging</strong> devastation: Solomon Islands is home to the last remainingforests in the eastern part of the Paradise Forests. In 2004, over onemillion cubic metres of logs were cut here, according to the CentralBank of Solomon Islands. This is four times the sustainable yieldof the remaining forests (which is 255,000 cubic metres per year,as calculated by AusAid, the A<strong>ustralia</strong>n Agency for InternationalDevelopment, October 2003). © Greenpeace/SolnessMany serious social impacts resulting from logginghave been documented over the last decade. Theseinclude: destruction of local water sources anddesecration of sacred and burial sites 23 , child sexualabuse and prostitution 24 , increased disputes andconflict within a community, the breakdown of socialstructures 25 , and hardship resulting from the loss anddamage to forest resources that local people rely onfor their every day living 26 .Environmental impacts have been equallydamaging and include: soil disturbance anderosion, sedimentation of streams and reefs, theloss of biodiversity and the regenerative capacity offorests 27 . It is also now well recognised that tropicaldeforestation and degradation is a major contributorto greenhouse gas emissions (equal to 1/5 of globalemissions) and dangerous climate change 28 .In some instances there has been a link betweenlogging and complete forest conversion for oilpalm plantations, where logging precedes theplantation development or is carried out under theguise of being an agricultural project 29 . With risinginternational crude palm oil prices there is increasedinterest in an expansion of oil palm, making forestconversion following logging a significant threat toSolomon Islands forests.2.Some of the most glaring failures of the logging sectorhave been in their financial affairs. A special audit bythe Solomon Islands Dept of Forestry, Environmentand Conservation in 2005 found that there was grossmismanagement in the forestry sector, and whilelogging companies were able to avoid paying muchof their tax liabilities, large sums of money were beingpaid to forestry officials and diverted to unbudgetedexpenditure 30 . The Auditor General conclusionsinclude:• In 2004, there was an estimated SI$29 million in forgonerevenue to the Government in the granting of timberduty exemptions.• Continuous breaches of agreement by the loggingcompanies• Unlawful ex-gratia payments, unaccounted foradvances made to individuals from logging companies,timber royalty payments diverted to private accounts…These types of practices are however not new.Problems with tax remissions and exemptionshave been previously identified 31 along with the‘severe economic and financial disruption when thenatural forest timber resource is depleted 32 . A majorA<strong>ustralia</strong>n Aid funded study in 1994 found losses tothe Solomon Islands Government of SI$94 milliondue to the underreporting of log prices 33 . There is noevidence to suggest that any of these practices andtheir resultant financial losses to the resource ownersand Government have abated in subsequent years,meaning the aggregate losses would now be in excessof a billion SI$.An oil palm kernel: the expansion of oil palm is a significant threatto Solomon Islands forests. © Greenpeace/BudhiSecuring the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy 7

Fi g u r e 1 : V a l u e o f W o o d P r o d u c t E x p o r t S c e n a r i o s - 2 0 0 8 t o 2 0 5 2 ( U S $ )3. COMPARATIVE FINANCIAL ANALYSIS - OF LOGGING FOR ROUND LOG EXPORTAND COMMUNITY ECOFORESTRY WITH SMALL-SCALE SAWMILLING.1 8 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 6 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 4 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 2 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 0 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 08 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 06 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 04 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 02 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 00Figure 1: Value of Wood Product Export Scenarios – 2008 to 2052 (US$)c u r r e n t e x p o r tr a te : 1 0 0 %r o u n d lo ge x p o r ts a tc u r r e n t r a tes u s ta in a b le r a te :1 0 0 % r o u n dlo g ss u s ta in a b le r a te :7 5 % r o u n d lo g s ,2 5 % s a w ntim b e rs u s ta in a b le r a te :1 0 0 % s a w ntim b e rs u s ta in a b le r a te :5 0 % s a w ntim b e r , 0 %r o u n d lo g s ,c a r b o n f in a n c eL a n d o w n e r / p r o d u c e r r e tu r nG o v t e x p o r t r e v e n u eLogs are tagged and ready to be shipped to Malaysia at a loggingcamp in Marovo Lagoon. © Greenpeace/BehringThis analysis calculates the Net Present Value (NPV)to the Solomon Islands Government (log tax andduties) and landowners (royalty and/or communityecoforestry profit) for both logging for roundlog export, and for a range of combinations withcommunity ecoforestry using portable sawmilling forsawn timber export and domestic use. Two differentresource harvest intensity scenarios were alsoanalysed – the current exhaustive ‘boom and bust’track of exploitation where commercial forests willbe logged out by 2015 and a ‘sustainable yield’ rateof harvest where there is an assumed non-declining248,000 m3/year 34 .All data for the analysis was sourced from the CentralBank of Solomon Islands 35 , the IMF (2007) and theMinistry of Forests, Environment and Conservation(2006), with supplementary data on communityecoforestry and small-scale sawmilling from VillageEcotimber Enterprises (VETE), Honiara.It is not a full economic analysis so the broaderflow-on socio-economic impacts – such as localemployment, housing, local services, and generalcontribution to the ‘quality of village life’ or the nationsGDP – of the two different tracks were not considered.The potential additional value of further processing ofand value adding to the sawn timber, or the broaderbenefits gained by Solomon Islanders controllingand managing their own resources were alsonot considered.While there are obvious short-term financial incentivesto liquidate the commercial forest resource as quicklyas possible, the greatest financial value (NPV) forthe nation is achieved through the substitution oflogging for round logs by community ecoforestry forsawn timber. For non-declining ‘sustainable rate’, thesubstitution of a quarter of the log production givesa 35% increase in value (see Fig 1). Any of the optionsthat involved the increased levels of local processingvia small-scale sawmilling and ecoforestry increasedthe value to the nation. The greatest financial valueis from the two scenarios that involved a ‘sustainable’rate of harvest and halting round log exports, eitherwith 100% community ecoforestry with sawn timberor the 50% community ecoforestry together with aforest carbon payment (see Fig. 1).1 8 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 6 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 4 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 2 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0Fig u r e 2 : L a n d o w n e r r o y a y a n d c o m m u n i t y p r o d u c e r r e t u r n o n e x p o r t s s a w n t i m b e r ( US $ )Figure 2: SIG Landowner Royalty and Community Producer Returns on Sawn Timber (US$)8 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 06 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 04 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 02 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 002 0 0 8 2 0 1 2 2 0 1 6 2 0 2 0 2 0 2 4 2 0 2 8 2 0 3 2 2 0 3 6 2 0 4 0 2 0 4 4 2 0 4 8 2 0 5 2L a n d o w n e r r e tu r n o n c u r r e n t 'b o o m a n d b u s t' r o u n d lo g e xp o r t r a teL a n d o w n e r r e tu r n o n n o n - d e c lin i n g r o u n d lo g e xp o r t r a teL a n d o w n e r /c o m m u n ity p r o d u c e r r e tu r n o n n o n - d e c l in in g e xp o r t r a te w ith r o u n d lo g a n d 2 5 % s a w n tim b e r e xp o r tsA portable saw mill in action. Portable sawmills are carried intothe forest reducing environmental impact by eliminating the needfor damaging infrastructure like roads. © Greenpeace/Neaves8 Securing the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy

350300250200150100500Fi g u r e 4 : R o u n d l o g e x p o r t s v s . l o c a l p r o c e s s i n gRound log exportsGovernment revenueLandowner/ producer revenueSmall scale sawmillingThe analysis shows there is a forestry path otherthan the current ‘boom and bust’ one, which isexpected to cause considerable economic hardshipand disruption when log exports dramatically dropfrom 2010 through to 2015. Immediately moving toa ‘sustainable’ harvest rate and transitioning awayfrom a focus and reliance on round log exportswould transfer considerable value and wealth tolandowners and community ecoforestry producers(see Fig. 2) and provide a moderate revenue streamfor the government (Fig. 3). This would prevent thescheduled massive collapse of revenue to landownersand government. However, the additional wealthof the landowners will mean greater income taxopportunities as a source of government revenue aswell as greater overall local economic activity that willsupport the provision of services.3.landowners this is 3-4 times the royalty received foran equivalent amount of round log harvested 36 (seeFig. 4). For the government it is only a quarter of thetax revenue they would get from round logs. Overall,community ecoforestry for sawn timber would be58% more profitable to landowners and governmentthan round logs for export. Community ecoforestrywould provide additional benefits like considerablevillage employment (particularly for young men),allow local communities to retain control over theirforest resources, provide permanent house buildingmaterials, as well as maintain the forest for existingcustomary uses, carbon financing and the needs offuture generations.Figure 4: Round Log Exports vs. Local Processing( S B D p e r o f r o u n d g )(SBD per m 3 of round log)Fi g u r e 3 : S IG a n c i a l r e t u r n o n e x p o r t s o f r o u n d l o g s a n d s a w n t im b e r ( US $ )Figure 3: SIG Financial Return on Exports of Round Logs and Sawn Timber (US$)2 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 8 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 6 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 4 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 2 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 01 0 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 08 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 06 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 04 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 02 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 002 0 0 8 2 0 1 2 2 0 1 6 2 0 2 0 2 0 2 4 2 0 2 8 2 0 3 2 2 0 3 6 2 0 4 0 2 0 4 4 2 0 4 8 2 0 5 2© Greenpeace/NeavesG o ve r n m e n t r e ve n u e o n c u r r e n t 'b o o m a n d b u s t' r o u n d lo g e xp o r t r a teG o ve r n m e n t r e ve n u e o n n o n - d e c l in in g r o u n d l o g e xp o r t r a teG o ve r n m e n t r e ve n u e o n n o n - d e c l in in g r o u n d l o g e xp o r t r a te w i th 2 5 % s a w n tim b e r a ll o c a ti o nFreshly milled eco-timber being stacked, ready for transport outof the forest. © Greenpeace/NeavesDetailed financial analysis of small-scale communityecoforestry, which focuses on exporting sawn timber,found it to be very profitable, with an average netprofit to the community of SI$1039 per m3 of sawntimber. However if total production, (includinglocal sales) is considered, the average net profit wasfound to be moderate at SI$624 per m3. A straightcomparison on a cubic metre basis found that forThis analysis includes in the production costs anallowance for forest management training andsupport to ensure forests are well managed and meetsthe standards of the world’s premium certificationschemes, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) andFair Trade, which would ensure access to high valueinternational markets. However, for current ecoforestryoperations, these costs are largely subsidised by donorfunded NGO support programmes - meaning currentactual profitability to landowners is higher.To support the rapid expansion of communityecoforestry and the retention of forests to maximiseeconomic, environmental and social benefits, theSolomon Islands Government and bilateral andmultilateral donors should consider funding expansivetraining and technical support.Securing the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy 9

4. VALUE OF ECOSYSTEM SERVICESMorovo Lagoon, Lobi Community, Solomon Islands - September8, 2004 -A man moves a tree with the use of a pully.Thisecoforestry project supports the local community and allowssustainable logging of their land. © Greenpeace/BehringServices provided by ecosystems include climateregulation, water supply and regulation, erosioncontrol, nutrient cycling, pollination, geneticresources, food and raw materials, recreation (e.g.ecotourism) and cultural/spiritual importance.‘Ecosystem services’ are currently not valued bymarkets based economies. A highly regarded researchteam estimated the value of ‘ecosystem services’ oftropical forests to the global community to be worthUS$2007/ha/year 37 . This means the value of theecosystem services for the 600,000 ha of SolomonIslands natural forest that is available for commerciallogging is equivalent to US$1.2 billion annuall 38 ,and much greater if all of the country’s forestsare included.4.While most of these ecosystem services are currentlynot given a monetary value, it is clear that they will bemore and more valued in the future. Several economiccost-benefit comparative studies 39 have shown thateven for forest products and services that have amarket value, small-scale and subsistence usesexceed that of large-scale industrial exploitation.For the Marovo region, the small-scale and subsistenceuses were found to be worth 3-4 times more tothe local communities than logging and oil palmdevelopment 40 .There is a fast evolving opportunity for tropical forestcountries to obtain payments for protecting thecarbon stored in forests. For greenhouse gas pollutingindustrialised countries this has been identifiedas a low cost way of mitigating dangerous climatechange 41 . To degrade or clear tropicalforest now means to forego this opportunity forsignificant income.If the stored carbon of the estimated 250,000 ha ofunlogged commercial forest remaining in SolomonIslands was ‘purchased’ (instead of logging the forest)then it could provide an immediate minimum returnof US$159 million 42 . There are an increasing numberof examples of forest conservation financing dealswhere ecosystems services are being valued and paidfor, such as through ‘Conservation Concessions’ 43 .In these deals, provided that participatory land useplanning has been carried out, different categoriesof land use that ensure forest conservation, areacceptable (including harvest of non-timber forestproducts, ecotourism, and community ecoforestry)thereby further extending the income opportunities.Therefore it makes good financial and economicsense to maintain and protect the forest for futureecologicially responsible use rather than trade justone of these ecosystem values (logs) for short-termfinancial gain to the detriment or destruction of theother values.Greenpeace strongly supports mechanisms tovalue ecosystem services and to transfer that valueequitably to those who own, have rights to, manage,or govern those forest ecosystems.10 Securing the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy

FOOTNOTES© Greenpeace/Neaves1 Ministry of Forests, Environment and Conservation 2006: Solomon IslandsForestry Management Project II, National Forest Resource Assessment Update2006. An AusAid funded project managed by URS Sustainable Development,Canberra, A<strong>ustralia</strong>. 1st Nov. 45p2 Ibid, and International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2007: Solomon Islands CountryReport: No. 07/304. Staff report for the 2007 Article IV Consultation.September. 72p,Solomon Is Ministry of Natural Resource (SIMNR) 1994: Solomon Islands NationalForest Resources Intentory: The forests of Solomon Is. Regional reports 1-9.Honiara. AIDAB and Ministry of Natural Resources.3 Office of the Auditor General 2005: Special Audit Report into the Financial Affairsof the Dept of Forestry, Environment and Conservation. National Parliament PaperNo. 8 of 2005. 74p,Asian Development Bank (ADB) 1998: Solomon Islands 1997 Economic Report.August.,Central Bank of Solomon Is 1995: Annual Report, Honiara, p18,Price Waterhouse 1995: Forestry Taxation and Domestic Processing Study. Finaldraft report. SIG Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Forests, Environment andConservation, Honiara,Duncan 1994: Melanesian Forestry Sector Study. Report prepared for AIDAB.October. 30p.4 Herbert 2007: Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Solomon Is: A reportfocusing on the presence of the logging industry in a remote region. A reportprepared by Tania Herbet for Christian Care Centre, Church of Melanesia, Honiara.July. 45p ,Olsen and Turnbull 1993: Assessment of Growth Rates of Logged and UnloggedForest in Solomon Is. Final Report. Solomon Is National Forest ResourcesInventory.,Greenpeace A<strong>ustralia</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> and Oliver 2001: Caught Between Two Worlds: Asocial impact study of large and small-scale development in Marovo Lagoon,Solomon Is. 24p.5 LaFranchi and Greenpeace <strong>Pacific</strong> 1999: Islands Adrift: Comparing Industrial andSmall-scale Economic Options for Marovo Lagoon Region of the Solomon Is.March. 21p + appendices.6 Solomon Star 2008. ‘<strong>Logging</strong> Drives Solomons Economic Growth: Statementsfrom the Central Bank Governor Rick Hou. February 19.7 IMF 20078 IMF 2007,Radio NZ International 2008: ‘SI GG warns against economy’s reliance on logging’18th March., Solomon Star 2008.9 SIMNR 1994,AusAid and Ministry for Forestry, Environment and Conservation 2003: SI ForestryMangement Project, Phase 6. National Forest Resource Assessment. Reportprepared by URS. October. 29p + appendices,Ministry of Forests, Environment and Conservation 2006.10 NPV is defined as the future stream of benefits and costs converted intoequivalent values today.11 Kabutaulaka 2000: Paths in the Jungle: Landowners, Deforestation and ForestDegradation in Solomon Islands. http://www.wrm.org.uy/deforestation/Oceania/Solomon Is,Fraser 1997: The struggle for Control of Solomon Islands Forests. The Contempory<strong>Pacific</strong>, Vol. 9, No.1, pp39-72.12 Duncan 199413 IMF 2007. Note: Round log exports for February 2008 alone exceeded 130,000 m3(CBSI 2008: Monthly Economic Bulletin. Issue No. 2, Vol. 1.).14 AusAid and MFEC 200315 Estimated at A$15-20 million, and according to URS the consultancy firmimplementing the project since 1999, the project was to “contribute to thesocio-economic development, peace building and the well-being of the peopleof the Solomon Islands and their environment by enhancing: the managementof natural forests, growth of the forest estate through plantation development,revenue collection (from log exports) by landowners and the Government, andthe capacity of the Forestry Division (FD) to effectively support and regulate thiskey sector of the Solomon’s economy.”16 SIMNR 199417 AusAid & MFEC 2003, MFEC 200618 <strong>Pacific</strong> Report 1994: ‘Malaysian Businessman Expelled from Solomon Islands afterBribery Allegation”. Vol. 7, No. 14, July 25.19 Solomon Star 1995: “$7 million Scam Surfaced.” November 10,Solomon Star 1996: ‘Orodani Returns to Court Today’. Oct 25.20 E.g. Court of Appeal of the Solomon Islands 1999: Gandly Simbe vs EagonResources Development Company Ltd. Judgement Report,Appeal No. 8 of 1997. 26p,Solomon Star 1998: ‘Earthmovers Ordered to Pay Workers.’ March,Pacnews 2008: ‘Forty-eight Asians illegally working in the logging industry aregiven seven days to leave or be kicked out’. 13th March ,Solomon Star 2004: ‘Logger Jailed’ 13th September.21 E.g. Solomon Star 2006: ‘Brother Bashes Anti-logging Sister’, Feb 6.,Solomon Star 2007: ‘Pro-loggers and Anti-loggers in Vella Lavella’ 17th August.,22 Martin Apa’s murder on October 30th 1995 has yet to be properly investigated bySolomon Is Police.23 Tausinga 1992: ‘Our Land, Our Choice: development of Nth New Georgia’ In:‘Independence, Dependence, Interdependence: the first 10 years of Solomon IsIndependence. USP, Honiara,WRM and Forest Monitor Ltd 1998: ‘High Stakes – the need to controltransnational logging companies: a Malaysia case study. August. Uruguayand UK. 57p.,Rukia 1989: ‘Impact of logging on Sacred Sites in Solomon Island: the Aola Case,Guadalcanal Island. Solomon Is National Museum Discussion Paper.,Fitzgerald 1993 Social Aspects of Forest Resources and Natural ForestManagement . Draft report for UNDP and UKODA, Honiara. November.24 Herbert 200725 Greenpeace and Oliver 200126 Ibid27 Olsen and Turnbull 1993, MFEC 1994: Distribution of <strong>Logging</strong> Revenue, Paper 1.6,proceedings of conference on forest policy and law, 25-27th November.28 Greenpeace International 2008: ‘Tropical Deforestation Emission ReductionMechanism (TDERM) – a discussion paper. Report written by Billl Hare and KirstenMacey. Amsterdam. 52p29 Office of the Auditor-General 2005: For example, in 1999 despite alarm bellsbeing rung by NGOs and local landowners, Malaysian company Silvania weregiven approval to develop an oil palm plantation project on Vangunu Is in Marovolagoon. To date only 700 ha has been planted and planting has stopped but thewhole plantation development area has been logged out.30 Office of the Auditor-General 200531 ADB 1998, Price Waterhouse 199532 ADB 1998 p6633 Duncan 199434 Ministry of Forests, Environment and Conservation 200635 Various annual reports36 Assuming a conversion rate of sawmilling of 40% - to produce 1 m3 of sawntimber would require 2.5 m3 of round log.37 Costanza etal 1997: The value of the world’s ecosystem services and naturalcapital. Nature. London: May 15. Vol. 387, Iss. 6630, pg 253.38 At 1997 US$ values39 e.g. Cassells 1992: Tropical Rainforest: subsistence values compared with loggingroyalties. Proceedings of Conference ‘Development that Works’ Lessons from the<strong>Pacific</strong>. Massey University, Palmerston Nth, New Zealand. August. 11p,Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society 1993: Big Bay National Park Proposal andOpportunities for Sustainable Development. Unpublished report. October. 65p +appendices.,Lafranchi and Greenpeace <strong>Pacific</strong> 1999.40 Lafranchi and Greenpeace <strong>Pacific</strong> 199941 Stern (Ed) 2007: ‘The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review’, CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge, UK.42 Assuming a conservative 150Mg C/ha (t/ha) of intact natural forest (rangesrecorded of 164 to 250 Mg C/ha. In: Gibb etal 2007: ‘Monitoring and estimatingtropical forest carbon stocks: making REDD a reality. Environmental ResearchLetters: 2: Oct-Dec 2007) and a carbon price of US$5/t C (Carbon prices rangefrom $5 to $30/tonne).43 Examples of forest carbon financing include Harapin forest in Sumatra, Indonesiaby Birdlife International, and 750,000 ha of forest conserved with the support ofan US$9 million carbon payment by US Banker Merrill LynchSecuring the Future: An Alternative Plan for Solomon Island Forests and Economy 11

www.greenpeace.org.au© Greenpeace A<strong>ustralia</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> LtdApril 2008PO Box 3307Sydney NSW 2001Phone: (+612) 9261 4666Fax: (+612) 9261 4588© Greenpeace/SolnessA<strong>ustralia</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong>