CO-OPERATIVES GOVERNANCE AND ... - fea-RP - USP

CO-OPERATIVES GOVERNANCE AND ... - fea-RP - USP

CO-OPERATIVES GOVERNANCE AND ... - fea-RP - USP

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>CO</strong>-<strong>OPERATIVES</strong> <strong>GOVERNANCE</strong> <strong>AND</strong> MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS: AN AGENCYTHEORY APPROACHPhD Professor Sigismundo Bialoskorski Netosigbial@<strong>fea</strong>rp.usp.brFEA-<strong>RP</strong>/<strong>USP</strong> - BrazilMSc Marcelo Barrosomarcelobarroso@<strong>fea</strong>rp.usp.brFEA-<strong>RP</strong>/<strong>USP</strong> - BrazilMSc Professor Amaury José Rezendeamauryj@usp.brFEA-<strong>RP</strong>/<strong>USP</strong> - BrazilAbstractCo-operative organizations have a particular structure to distribute its propertyand decision rights that implicate on management problems and on transaction costs.Such structure creates equity rights and risk transfers that directly affect the selfmanagementefficiency of these organizations. This paper analyses these costs andinefficiencies sources to explain its problems in two complementary and differentways. The first discuss the governance aspects that generate agency conflicts whilethe second analyses the characteristics of managerial systems which generateinformational asymmetry and monitoring problems.An analysis of the property rights distribution among members, decision rightsdistribution among elected members and hired executive professionals, indicates thatequity rights and risks division in co-operative’s contractual relations allow to typifythe governance, the management model and managerial information systemcharacteristics, that could reduce agency problems. The methodology is thetheoretical discussion, and the comparison the management models and systems ofrural credit and agricultural cooperatives in Brazil. A questionnaire is applied in fivecooperatives to compare managerial models and systems. In final considerationsshould indicate that better co-operative management models organization andmanagement systems could reduce their agency costs.Key-words: co-operative governance, management systems, agency costs,transaction costs.

1. IntroductionTo analyze organizational efficiency under economics of organizationsperspective, it is important to consider decision making and strategic planningprocesses using two complementary perspectives, control and decision powerdistribution – governance perspective – and value and availability of information –management control systems perspective.Dietrich (2001) argues that to systematize the knowledge about control in anorganization, we must analyze its structure, dependant on its governance anddecision rights division, and its process, dependant on information flow and,therefore, on managerial system characteristics. So, both dimensions may classifysuch processes.Regarding organizations, they may be classified as different categoriesaccording to Bialoskorski Neto (2006). The first includes organizations with profit asmain economic objective - for-profit - with a control, structure and process systemsentirely directed to activities which generate revenue and control based on economicfinancialnumbers.The second includes organizations without economic or profit objectives,aiming to provide social or public services, called non-profit. In such organizations thecontrol is directed to provide services, with rare concerns about the economicefficiency of factor allocation, but frequently the control concerns about socialdimension of the services provided, normally expressed in social indicators and not ineconomic-financial numbers.The third category, directly related to this paper, characterizes theorganizations with an economic objective without aiming profits. These organizationsare called not-for-profit and have both economic and service provision objectives. Insuch organizations, the control system in both structure and process perspectives ismore complex than previous cases, demanding monitoring of both economic andservice provision results. The agricultural co-operatives are classified in this category.Thus, the discussion about management control systems characteristics innot-for-profit organizations in the focus of its governance complexity is fundamental,taking for example agricultural co-operatives that have particular characteristics incontrol processes and structure, with the last one deeply related to particular cooperativegovernance characteristics found in our research.This paper aims to describe the control processes and structures in not-forprofitorganizations, specifically agricultural co-operatives. Therefore, it analyses twocompletely different examples – one with property separated from control, andanother without it –, in order to analyze the different control structures andprocedures as well as the managerial systems importance.2. Incentives and agency costsThe organizational characteristics of co-operatives, according to theirdoctrinaire fundamentals, define a particular distribution of property, decisions andresults among its members. Such distribution directly influences its co-operativegovernance and the professional manager’s role.2

In a co-operative, the members have a unitary decision right – one member,one vote – in the general assembly, electing and delegating to member’s bodyleaders those rights. Otherwise, these leaders delegate for co-operativeprofessionals a specific decision right about business and services provision to itsmembers.The operational financial results – income residuals – could are invested in theco-operative or distributed among members proportionally to each one participationon it. In this conjuncture, emerges an agency problem of encouraging theprofessional co-operative body to act according to the member’s desire, since theequity is distributed to members and not to professionals.Jensen and Meckling (1976) describe the agency problem as situation whereone part – the principal – is responsible to hire a second part – the agent – whichmust act accordantly to the principal interests. In such situation, the authors predictthat the agent will always try to maximize its own interest, even though it diverts fromthe principal’s interest. In co-operatives, the professionals are the agents that shouldact on behalf of co-operative members only, but may not do so.In co-operatives, agency problems are more evident and also implymanagement costs, analyzed as governance problems such:a) Costs caused by the principal efforts to monitor agent attitudes, to reducelosses caused by the agent acting on its behalf in prejudice of principal’sinterests. These costs represent the ones that occur by the member’sboard and fiscal council to monitor and control the hired managers body;b) Contractual costs created by the agent commitment with the principal, inother words, the efforts to keep the contractual relations of acting on behalfof another’s interest. These costs represent the ones taken by professionalmanagers to act accordantly to members’ decisions, even though they arenot always efficient to the organization;c) Costs generated by a reduction in the principal results induced by naturalorientation and decision divergence between the parts. This important costelapses from the fact that the agent – hired managers in this case – tendsto act on its own behalf in some questions which are hard to monitor bymember’s body and council - , raising hired professionals’ revenue inprejudice of co-operative revenue.The Figure 1 below shows the relation between co-operative members asprincipals and co-operative professional body as agents that should act on behalf ofmember’s interests (situation A). It also shows the relation where financial investorsmight be considered principals while professional managers are agents that must actaccording to the economic efficiency interests of these investors (situation B). Yet, itshows when the co-operative organization is principal to the member’s agents thatshould be motivated to keep a close relationship with the co-operative and producewith substantial quality and quantity to achieve the collective interests of theorganization (situation C).3

Government AgenciesGeneralAssemblyPrincipalAgentBPrincipalCooperativeAgentAFinancial InvestorsManagersPrincipalCMembersAgentFigure 1 – Agency relationships where A, B and C identifies the relations and sources of costs.Bialoskorski Neto (2006).All these relations have incentive problems and monitoring costs as describedbefore. Therefore, it is important to notice that co-operatives’ organizational structurehas several sources of transaction costs that could be minimized using governancebest practices, efficient management control systems, and more transparentmanagement by the hired professional.It is also important to notice that in all cases the principal and the agent canavoid or be neutral to get risk. If the agent is risk neutral, Milgron e Roberts (1992)explain that contractual incentives like variable remuneration based on equity mightbe an excellent incentive to increase efficiency and conduct these activities toprincipal’s interest. On the contrary, when the agent avoids risk, only the fixedremuneration part will be accepted, and different incentive and control methods mustbe used.We can also analyze the situation using by the principal‘s perspective. If theprincipal is risk neutral, he might be willing to risk more and it raises its expectationfor the variable remuneration part – i.e. equity. Otherwise, if the principal avoids risk,just an immediate remuneration on services or prices advantage will be acceptable inthe co-operative.Depending on the agency relation and degree of risk aversion, it is possible tohave different arrangements between principals and agents, incurring in differentsituations of financial results appropriation efficiency, in other words, in different cooperativestrategies to generate benefits though its equity distribution by the end of adetermined period. In Brazilian co-operatives, is given the high agricultural producersrisk aversion, the most used arrangement do not distribute equity directly, but insteadfree services, better inputs prices and payment conditions to co-operative members.4

The Box 1 below describes the possible situations related to equity rights when themember is the principal and the professional management body is the agent:TraditionalBrazilianCo-OperativeNewGenerationCo-OperativeMember(Principal)Avoids riskAvoids riskRisk neutralRisk neutralManager(Agent)Avoids riskRisk neutralAvoids riskRisk neutralEquity RightsBoth parts demand fixed benefits withoutvariable parts, and there is no agentincentives in case of equity, that becomesunavailable.The member demands fixed benefits, butthe agent – co-operative professional –might appropriate a variable part. Forexample, the variable remuneration todirectors and technical assistance staff.Variable equity part appropriated by theprincipal – the member – as incentive,while the co-operative professional –agent – prefers the traditionalarrangement.Without fixed parts or benefits, andvariable equity distributed as incentive toboth, principal and agentBox 1 – Relations between degree of risk aversion and equity distribution in co-operatives (made bythe authors)The Box 1 above classifies the co-operatives and explains its most commoncontractual incentive strategies to guarantee that the agent acts on behalf onprincipal’s expectations. In Brazilian co-operatives, the situation where both principaland agent avoid risks is usual. The total risk neutral situation is its opposite andalready could happens on New Generation Co-operatives, where contractualincentives are based on variable earning parts to both principal and agent(BIALOSKORSKI NETO, 2004).The intermediate situation might also happen, but the risk neutrality might befrom the agents – co-operative professionals –, that accepted a significant variablepart of their remuneration as an incentive to their efforts, since they are not financialoperations guarantors. Otherwise, this characteristic might not be ideal to the cooperativedue to possible noxious efforts of risk neutral professionals to co-operativemembers, for example in case of commissioned technical assistance that incentivesthe use of unnecessary resources by co-operative members, associates andagricultural producers.Therefore, the situation where both principal and agent avoid risks is mostcommon and needs control tools and monitoring process to incentive the agent to actaccording to the principal’s interest.3. Management models and typologyWhen applying these concepts to corporate governance, and if the managerrole is known, an institutional analysis also allows us to notice that the main cooperativedoctrinaire principles have a direct influence in the success of theorganization (BIALOSKORSKI NETO, 2004):5

a) The democracy principle demands high transactional costs due todecisions taken in general meetings and councils, sometimes complex withconflict;b) The equality principle of one member, one vote, directly implies in highagency costs due to lack of objectiveness and focus in co-operative’seconomical and business activities;c) The principles of solidarity and equal results distribution, according to theoperations, sometimes make an impossible view of clear property rights,and not permit a perception of the member as an investor, leading to highagency and transactional costs.These co-operative organizations problems and characteristics reflect theneeds for different corporate governance parameters to improve economic efficiencyand the management body professionalization.All governance problems described above happen due to co-operativesorganizational architecture and doctrinaire principles, but besides these limitations wealso find co-operatives with different governance and professionalizationadjustments.In Brazil, it is possible to classify the co-operatives management models in twodifferent ways, according to their professionalization degree, and the border betweenthe ownership and control. Each model can be analyzed according to its agencyproblems and costs to elaborate a corporative governance and management modelstypology.In the first management model, most frequent in Brazilian co-operatives, themembers delegate their power to an administrative council, most times notprofessionalized, and also elect a board of directors generally formed by agriculturalproducers’ members, not necessarily professionalized, that becomes responsible forthe co-operative executive management. Other workers are professionalized withlittle decision autonomy and respond directly to the board of directors. In this model,the president of the cooperative is the CEO, and in the same time, the president ofthe administrative council.The second management model type appears in bigger agribusinessco-operatives, but it is less frequent. It is characterized by a contracted professionalsuperintendent or general manager – CEO - that is responsible for the co-operativemanagement, and intermediate the contact between the administrative council andworkers’ body. Most times has decision autonomy over the co-operative, with apossible part of its wage proportional to the results achieved. It is the model called“professionalization” in Brazil. In this model the cooperative president is theadministrative council president, and de CEO is the cooperative manager.The first model has classical governance problems, with a frequentlyprofessionally unprepared board of directors with insufficient knowledge to prepareefficient businesses policies. In this model is necessary a management informationspecially prepared to the board could prepare the decision making process. Thismodel could also induces a situation where the agent – the hired professional – isalso principal, in other words, it is both co-operative member and interested in thebusiness strategic success. Otherwise, nothing impedes the agent and the principalto achieve the best possible benefits for them using asymmetric and privilegedinformation.6

The second model has the agency problems mentioned, that can beminimized using adequate management control systems and information flows, sincethe professionalized manager – CEO - might be distant of the co-operative member’sreality and members might also be distant of the co-operative and its administrativereality. In such cases, monitoring costs by the members – the principal in thecontractual relation – are higher than opportunity participation costs, andconsequently the role of the professional manager is to reduce the informationasymmetry and agency cost in the process.In this way, managerial information systems are fundamental to reduceagency costs and information asymmetry in all cases. In the first, to improve thedecision process by providing decoded information to not professionalized board ofdirectors, and prevents the use of privileged information.In the second model management system is important to provide to membersa better control over the professional manager – risk neutral – procedures andhomogenize the risk acceptance criteria.4. Management control systems and information asymmetryManagement accounting has been criticized for not being able to fulfil itsobjectives. Some authors criticize accounting data for not being a reliable source ofinformation to analyze businesses performance (PEEL and BRIDGE, 1998, p. 853;BRACKER and PEARSON, 1986, p. 505) or to subsidize strategic planning processbecause, as affirm Mintzberg et al. (2004, p. 60), factual information like managerialaccountability information:[...] frequently has a limited scope, richness gaps and most times does notinclude important non-economic and non-quantitative factors;[...] are over aggregated to be efficiently used in strategic planning;[...] arrives too late to be used in strategic planning; and[...] most of it is untrustworthy.DeLone and McLean (1992) discourse about an in depth model based onuser’s individual analysis with six different taxonomy success categories thatcontribute to information system effectiveness: system quality, information quality,information system usage, user satisfaction, individual impact and organizationalimpact. Seddon (1997) deliberates about this model proposing other relations andopposing the previous idea of information system usage as a proxy to the benefitsgenerated by user, introducing the behavioural information system usage category.His model considers three different variables: system quality and informationmeasures, information systems usage general net profit measures and behaviourrelated to information system usage (RAI et al., 2002).The DaLone and McLean model considers the user voluntarily uses theinformation system, while the Seddon model considers that its usage is both avoluntary and involuntary choice. Rai et al (2002) considers the semi-voluntaryinformation system usage as a presupposition, given the fact that manager’s jobdescriptions defines tasks and responsibilities but not if they will be done usinginformation systems or not, letting each one identify alternative methods to realizethem. However, some tasks might be strictly information system dependant, givingthe user no alternative methods to realize them. (GOODHUE and THOMPSON, 1995apud RAI et al, 2002).7

Speklé (2001) proposed a model addressing the description of managementinformation systems variation based on economic transaction costs theory. Suchapproach has been used to explain discrete governance structures, notedlyorganization of transactions via market, hierarchy or hybrid forms, and can also beused to describe management information systems, also discretely variable.For instance, in management control systems such theoretical arrangementcan be understood as different efficient solutions to contractual incentive problemsthat appear when hiring or controlling in organizational architecture. The agent’sefforts and their contributions to the organizational results are also functions ofmanagerial monitoring and control structures aiming to maximize the economicefficiency.Together with the description of discrete governance structures based oncharacterized variables, the author suggests three variables to differentiatemanagerial control structures: a) previous uncertainty level about the desired effort,b) human asset specificity level of resources involved in the competencies and, c) theimpact intensity of the information available after the agency effort.The agent uncertainty about the efforts and contributions desired by theorganization to accomplish the objectives exists due to the possibility of planning theeffort previously. In that case, given the impossibility of planning the desired effortpreviously, it is imperative that the organization has monitoring flexibility to allowcontractual adaptations to unpredictable events.Regarding asset specificity level of human resources involved in the process,it is related to possible value loss of allocating these resources in differentalternatives to previously designated ones, like the view on economic transactionscosts. Therefore, for the management control systems structure view, the resourcesinvolved are individual competencies allocated to organizational tasks.The third variable refers to the impact in contractual relation of the effortresults by comparing real performance to previously defined organizationalobjectives. This variable must be specially considered when it is impossible topreviously plan the effort, in other words, when there is a high uncertainty levelrelated to individual agent’s efforts. Such uncertainty must disappear as the activitiesare being performed and the perception of contribution performance becomesclearer. In some situations, however, this information continues to have a higherorganizational impact due to its specialized nature or impossibility of protecting themfrom its owner opportunism. In such cases, management control mechanisms thatnormally try to guarantee the realization of the desirable contributions act to preventundesirable contributions.8

Low human resourcesasset specificity(The resources can thereallocated and acquired inthe market)High human resourcesasset specificity(The resources cannot bereallocated and are trainedinternally)Low uncertainty – Highability to plan the agentefforts previouslyManagement control systemmade by ex-post informationwith high impact to agents.Management control systemmade by ex-post informationwith low impact to agents.Can generate opportunisticattitudes by agents.High uncertainty – Lowability to plan the agentefforts previouslyClear Management controlwith precise ex-anteinformation and complexmonitoring.Clear Management controlwith ex-ante information,complex monitoring,hierarchal preciseinformation and highinformation efficiency tomonitor and avoidopportunistic attitudes byagents.Box 2 – Management control systems classification according to human resources asset specificityand ability to previously plan the activities and its uncertaintyIn that way, there are different information systems and managerial needs toeach combination of previously described variables. For example, low uncertaintywith high ability to plan agent’s efforts previously, high human resources assetspecificity and high information impact to monitor agent’s efforts would imply inmanagement control systems less complex but with great efficiency.Otherwise, high uncertainty with low ability to plan agent’s efforts previously,low human resources asset specificity with low information impact to monitor agent’sefforts would imply in complex management control systems to gain some efficiencylevel.5. Co-operatives and management control systemsThe previous discussion about management control systems efficiency alsoapplies to co-operative organizations. Therefore, in co-operatives exists the specificsituation presented on Box 1, where the general assembly and the board of directors,in other words the members themselves, have the principal role while the cooperative’smanagers, including directors, managers and superintendents, have theagent role to act on behalf of the co-operative members.As suggested in corporate management model typology section, it is possibleto classify the rural credit and agricultural co-operative management model in twodifferent ways, according to its contractual principal-agent relation. Uncertainty,resources specificity and impact of available information on the agent’s contributionmust be analyzed to suggest the best control structure in each model.In the first model, the general assembly elects a non professionalized board ofdirectors and delegates them power to take strategic and tactic business decisions.The second model has the superintendent role, a professional manager hired in themarket – CEO - who is responsible for tactic business decisions, but shares with theelected board of directors the strategic decisions responsibility.9

Beginning by the uncertainty characteristic, it is possible to verify that in allmodels it is impossible to plan the co-operative manager’s contribution previously,irrespectively if they are elected managers or hired professionals, since their maincontribution is through strategic and tactic decisions that lack previous deducibleinformation. Therefore, in all contractual models discussed before the controlstructures are based on a low ability to plan the agent’s efforts previously, resulting incontractual relations strongly based on mutual confidence and commitment withvague desired contributions limits.The manager’s contribution to co-operative’s objectives is in function of theinvolved resources level. The main manager’s contributions resources are individualallocated competences, specially knowledge and skills. As suggested by Speklé(2001, p428), “low resources specificity implies in a purposely general desiredcontribution, do not involving tailored organizational resources”. That way, “theircontributions are probably driven by market mechanisms”. That might be theprofessional managers situation in second model, since they were hired in themarket, but possibly this situation does not happen in the first and third models,where there are some specificity in the competencies allocated by members electedto the board – even though they are not professionalized.Unpredictable situations will also demand decisions, even with an insufficientknowledge about the course of action that can lead to better results. In such cases,the decisions will be taken based on available information generating newinformation derived from such decisions that will allow new decisions to achieve theco-operative objectives.The information heap about contributions performance disperses inasymmetric and powered way through the organization, precluding to only oneindividual to have all information made available. In management control perspective,the challenge in such cases becomes to completely disseminate corporateperformance information in real time. That is, in situations with high uncertainty andresources specificity the organization shall minimize the high impact condition ofinformation, third control structure characteristic analyzed.Compiling the described characteristics in the two models verified on cooperatives,and based on the previously stated variables, it is possible to compoundthe Box 3 below.10

ModelM1Human resourcesasset specificityAgents riskaversionUncertainty(informationasymmetrybetween Principaland Agent)Unpredictability(operationspredictability toachieve the cooperativeobjectives)Post hocinformationimpactGACouncil /Board ofdirectors notProfessionalHigh.Frequently notprofessionalizedelected board ofdirectors not mightbe replacedwithout significantcosts.(+)Producershighly averse torisk(+++)Low asymmetry.The producersare principal andagent at thesame time(+)High due to lack ofprofessionalizationand predictableactions, since themembers are agentsand principals in thesame relation (+++)low informationimpact due to thepossibility of notsubstitute theboard of directorseasily(+)M2GACouncilLow. The hiredmarket professionalcan be substituted,but not withoutlosing experience(-)Risk neutralprofessional(/)High informationasymmetry andpossibility of highagency costs(+++)Low, due toprofessionalizationand predictableagent monitoringefforts(+)High informationimpact(+++)SuperintendentBox 3 – Classification of essential information systems attributes and management models in cooperativeorganizations.6. Survey and Cases StudiesBoxes 2 and 3 shows that each cooperative organizational architecture, couldimply in a specific management system to maximize the organizational efficiency,control, and management methods.Considering the all credit cooperatives in Brazil, in according Brazil Central Bank,70,14% of all cooperatives have a elected director with executive functions includingsalary – M1 model, and others 29,5% have contracted executive – M2 model. In78,5% of the cooperatives the president elected is also the president of executiveboard. 2/3 of all cooperatives not have managerial instrument to evaluated theadministrative council, fiscal council and executives directors performance(VENTURA, FONTE FILHO, e SOARES, 2009). Same survey shows that 63,6% ofall cooperatives members to not became a member because the economicadvantages of the cooperatives and 31,9% became member because socialnetworking and associative vinculum.11

Box 4 shows which are management control systems expected to each kind ofcooperative management models, and which are the economic incentives moreefficient to the agents.M1ModelManagement control systemscharacteristicsResults and incentives appropriationM2GACouncil /Board ofdirectors notprofessionalManagement control systemcomposed for ex-post information withhigh impact in agentsDemand for fixed benefits without variableparts, and there is no agent incentive incase of equity, that becomes unallocated.GACouncilClear management control systemwith precise ex-ante information andcomplex monitoring.The member demands fixed benefits, butthe agent – co-operative professional –might appropriate a variable part, likevariable remuneration.SuperintendentBox 4 - Classification of the managerial information systems characteristics and management modelsin co-operative organizationsThese two different management models are identifying in rural creditcooperatives in Minas Gerais State. A on-line questionnaire was elaborated with 90questions about the cooperative identification, numbers of members, assets andfinancial numbers, considerations about the administrative council, functions of themembers, presidency, presidency of the council, educational level, presence ofcontracted executives, and about the existence of financial incentives to thepresidency, board, executives and professionals. Also, a detailed questions aboutmanagement systems characteristics, including informational flows, kind ofinformation, management instruments like cash flows, budgeting, demonstrativesetc. Some questions is in the evaluation scale 1 to 5 to measure variable intensity.Was chosen, of all questionnaires, five cooperatives to an initial analyse, like amulti case study, which must be similar in core agribusiness area, similar in numberof members and financial size, and could be a sample of the management modelsstudied and could be a sample of use of management and control systems. Table 1show the cooperatives characteristics.12

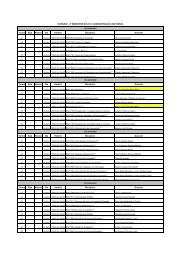

Table 1. Cooperatives sample survey selected data.General InformationCooperatives Agribusiness system core Assets Thous USD Members Employees Councill Members Directors ExecutivesM1 Coop A Dairy and Grains $ 12.105,26 1,874 15 6 3 0M1 Coop B Dairy $ 10.308,02 1,777 24 6 3 0M1 Coop C Dairy and Grains $ 7.067,39 1,716 22 5 3 0M2 Coop D Dairy and Grains $ 23.860,26 4,619 57 6 3 3M2 Coop E Dairy and Grains $ 14.136,16 2,071 22 6 3 1Selected answersCooperatives Autonomy Incentives Well Manag Syst Control Decision Centralized Month Semestral Not useM1 Coop A No No Yes (5) No (2) BS and Others Fin DemM1 Coop B Relatively No Yes (4) No (1) Others Inform FD and BSM1 Coop C No No Yes (4) No (2) Others Inform FD and BSM2 Coop D Relatively No No (2) Yes (5) Others Inform FD and BS Cash FlowM2 Coop E No No No (1) Yes (5) FD and Others B. Sheet Cash Flow(scale 1 bad to 5 good) (scale 1 bad to 5 good)BS - Balance Sheet / FD -Financial demosntratives/ OI-Others informationSource: Authors survey

All cooperatives chosen, protected its identity, have activities or only in dairyproducts, or in dairy and grains products. The size of the five cooperatives isapproximately the 13 until 45 millions of Reais in assets, middle size rural creditcooperatives, and 1,7 to 4,6 thousands of members each one, also middle sizecooperatives. With these numbers is possible consider these cooperatives similar insize and compare these five cooperatives as a sample.As the questionnaire is very detailed, of all questions answered some areimportant to analyse the differences and similarities among management models,and is significant to this discussions.All cooperatives, independent of the management models, declare that there isnot a salary variable part like contractual incentive to the professionals, contractedexecutive or for the members of the board. So, there is not a financial incentives toprofessionals achieve goals, differently of the management systems theory andagency theory appoint as the best solution.An important characteristic is that all cooperatives classified like M1 model, wherethe board members are also cooperative executives have the strategy to put 90%until 100% of its financial results in nom divisible funds; so, show high risk aversionbehaviour. Only one cooperative M1, where the rural producer board members andcooperative executive not have a high educational level - declare others forms todistributed results to the cooperatives members and present a high level of selfinterestin management and not with the organization, but is a isolated case.In terms of autonomy of the contracted professionals’ and employees allcooperatives declare that not have autonomy or have a little autonomy only, andshow the high preoccupation with business control and managerial systems with exanteinformational control. Not appear in this managerial systems a ex-post control toprofessionals goals; so, show more look for the ex-ante control that the flexiblebusiness practices with ex-post goals controls.All M2 cooperatives, with an executive contracted, agree that the managerialsystems are simple and not adjusted to the cooperative, and also the informationalprocess not monitoring, control the cooperatives activities, and not facilitated theinformational process. This answers show that executive professionals are probablyexigent in management systems and in monitoring and control activities.All M1 cooperatives agree in other side, in this question, that the process is ableto monitoring and create informational ways. In this case the answers show that theboard members and members with executive functions not have problems orexigencies with the management systems and probably could have information andcontrol for another ways.Other same position is about the centralized decisions in cooperativesmanagement. All of M2 cooperatives agree the decision process is high centralizedin the members’ board and explain for more flexibility and activities independence forthe professional executives.In function of the managerial systems, like cash flow, financial demonstratives,budgeting, etc., one characteristic is important the cooperatives with M2 structuredeclare that not use cash flow, like the M1 cooperatives, maybe in function that cashflow is a management system that permits the control on time and not is the bestinstrument to permit the ex-ante control. This result could show a controlpreoccupation in M2 structure, and an on time administration in M1 model.All cooperatives declare that management systems and information not have thefunction to inform the member, but only the cooperative staff and directors. So, there

is not preoccupation by the managers to inform the members about the cooperativeperformance.There are not others particular characteristics in management instruments useand is impossible identify any characteristic inherent to one or another group infunction of managerial systems instruments.For all others questions not have with the groups a common and particularcharacteristics of answers in function of the management model determined, thatcould be relevant. Nowadays the research program wait for a number ofquestionnaires answered to permit a statistical model and could enlarge theseresults.7. Final considerationsManagement control systems must support the monitoring actions flowminimizing information asymmetry and with efficiency to principals’ obligations. Inother words, they must not only define the appropriate policy to executeorganizational objectives and strategies, but give directions to organizational affairs,especially to principals that exercise supervision or monitoring rules.Case studies show, and the questionnaire answers appoint in this directionthat in M2 model needs clear management control system with precise ex-anteinformation and complex monitoring. In another hand M1 model use managementinstruments that permit on-time control and highly risk aversion. Also, the variablefinancial incentives to professionals or executives achieve business goals not exist inall models, contrary to the initial presumptions. The M1 model is the model with moreself-interest of the members including results distributions with others forms.Analysing the managerial instruments in the management systems the cashflow is important to control ex-post activities and it is relevant to M1 cooperatives andnot to M2, which have probably an ex-ante more efficient control.Also, is possible consider that in the theoretical point of view the cooperativerural producer member needs information about his enterprise to monitoring theboard and the executives activities, but in all cases the cooperatives declare that therural producer member is not a subject of the management systems function, or it isnot important to the cooperatives inform adequately the members.In this way all cooperatives declare that the management systems wereestablish not to give information to the members, but only to the board andprofessionals maybe in function that this information could not important to themembers’ day-a-day activities, since around 2/3 of the rural producers’ members notlook for the economic advantages to became cooperative member.At long last, discussing the adequate management control system to each cooperativeis very convenient, identifying members’ needs, increasing theirinvolvement with the co-operative routine and propitiating the best economicefficiency for the organization. According to Davis and Bialoskorski Neto (2007), it isthe Co-Operative Management of its Social Capital.This is an important agenda to further investigation, since the co-operativerelationship with its members is fundamental to raise its transactions fidelity. Theresearch next steps will be waiting for the sufficient questioners’ answers to elaboratea statistical analysis about the models and the management systems and adjust theinitial model presumptions.15

ReferencesATKINSON, A.; KAPLAN, R. S.; BANKER, R. J. Contabilidade Gerencial. São Paulo:Atlas, 2000.BIALOSKORSKI NETO, S. . Member participation and relational contracts inagribusiness co-operatives in Brazil. The International Journal of Co-operativeManagement, v. 3, p. 20-26, 2006.______. Gobierno y papel de los cuadros directivos en las cooperativas brasileñas:estudio comparativo. Revista de Economía Pública Social y Cooperativa, Valencia, n.48, April 2004.BRACKER, J. N.; PEARSON, J. N. Planning and financial performance of small,mature firms. Strategic Management Journal. v. 7, n. 6, p. 503-522, 1986.CLARKE, P. J. The old and the new in management accounting. ManagementAccounting. v. 73, n. 6, p. 46-51, 1995.DAVIS, P.; BIALOSKORSKI NETO, S. Gestão do capital social em cooperativas:uma abordagem baseada em valores. Working Paper. FEA-<strong>RP</strong> <strong>USP</strong> 2007 (mineo).DELONE, W. H.; MCLEAN, E. R. Information systems success: the quest for thedependent variable. Information Systems Research. v. 3, n. 1, p. 60-95, 1992.DIETRICH, M. Accounting for the economics of the firm. Management AccountingResearch. v.12, p. 3-20, 2001.JENSEN, M.; MECKLING, W. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, AgencyCosts and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics. v. 3, n. 4, p. 305-360, 1976.MILGROM, P.; ROBERTS, J. Economics, organization e management. New Jersey:Prentice Hall, 1992. 619 pp.MINTZBERG, H.; AHLSTR<strong>AND</strong>, B.; LAMPEL, J. Safári da estratégia: um roteiro pelaselva do planejamento estratégico. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2004.PEEL, M. J.; BRIDGE, J. How planning and capital budgeting improve SMEperformance.SPEKLÉ, Roland F. Explaining management control structure variety: a transactioncost economics perspective. Accounting, Organizations and Society. v. 26, p. 419-441, 2001.SEDDON, P. B. A respecification and extension of the DeLone and McLeanmodel of IS success. Information Systems Research. Set., v. 8, n. 3, 1997. p. 240-253.RAI, A. ; LANG, S. S., WELKER, R. B. Assessing the validity of IS successmodels: an empirical test and theoretical analysis. Information Systems Research.Mar 2002, v. 13, n. 1., p. 50-72.16

VENTURA, E.C.F. FONTES FILHO, J.R. e SOARES, M.M. (Coord) Governançacooperativa: diretrizes e mecanismos para fortalecimento da governança emcooperativas de credito. Brasília: Banco Central do Brasil. 200917