Study and Discussion Questions for Early Buddhist Discourses

Study and Discussion Questions for Early Buddhist Discourses

Study and Discussion Questions for Early Buddhist Discourses

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

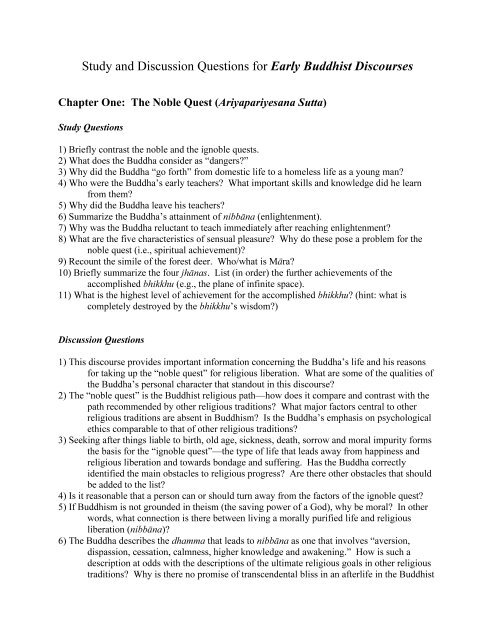

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter One: The Noble Quest (Ariyapariyesana Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Briefly contrast the noble <strong>and</strong> the ignoble quests.2) What does the Buddha consider as “dangers?”3) Why did the Buddha “go <strong>for</strong>th” from domestic life to a homeless life as a young man?4) Who were the Buddha’s early teachers? What important skills <strong>and</strong> knowledge did he learnfrom them?5) Why did the Buddha leave his teachers?6) Summarize the Buddha’s attainment of nibbāna (enlightenment).7) Why was the Buddha reluctant to teach immediately after reaching enlightenment?8) What are the five characteristics of sensual pleasure? Why do these pose a problem <strong>for</strong> thenoble quest (i.e., spiritual achievement)?9) Recount the simile of the <strong>for</strong>est deer. Who/what is Māra?10) Briefly summarize the four jhānas. List (in order) the further achievements of theaccomplished bhikkhu (e.g., the plane of infinite space).11) What is the highest level of achievement <strong>for</strong> the accomplished bhikkhu? (hint: what iscompletely destroyed by the bhikkhu’s wisdom?)<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) This discourse provides important in<strong>for</strong>mation concerning the Buddha’s life <strong>and</strong> his reasons<strong>for</strong> taking up the “noble quest” <strong>for</strong> religious liberation. What are some of the qualities ofthe Buddha’s personal character that st<strong>and</strong>out in this discourse?2) The “noble quest” is the <strong>Buddhist</strong> religious path—how does it compare <strong>and</strong> contrast with thepath recommended by other religious traditions? What major factors central to otherreligious traditions are absent in Buddhism? Is the Buddha’s emphasis on psychologicalethics comparable to that of other religious traditions?3) Seeking after things liable to birth, old age, sickness, death, sorrow <strong>and</strong> moral impurity <strong>for</strong>msthe basis <strong>for</strong> the “ignoble quest”—the type of life that leads away from happiness <strong>and</strong>religious liberation <strong>and</strong> towards bondage <strong>and</strong> suffering. Has the Buddha correctlyidentified the main obstacles to religious progress? Are there other obstacles that shouldbe added to the list?4) Is it reasonable that a person can or should turn away from the factors of the ignoble quest?5) If Buddhism is not grounded in theism (the saving power of a God), why be moral? In otherwords, what connection is there between living a morally purified life <strong>and</strong> religiousliberation (nibbāna)?6) The Buddha describes the dhamma that leads to nibbāna as one that involves “aversion,dispassion, cessation, calmness, higher knowledge <strong>and</strong> awakening.” How is such adescription at odds with the descriptions of the ultimate religious goals in other religioustraditions? Why is there no promise of transcendental bliss in an afterlife in the <strong>Buddhist</strong>

tradition? With relatively mundane goals like “aversion” <strong>and</strong> “dispassion,” is Buddhismopen to the charge of pessimism?7) The Buddha was at first reluctant to teach to others the dhamma he discovered. Why? Werehis reasons good ones? Why did he change his mind? Does one have an obligation toshare such a discovery?8) In a curious (perhaps even embarrassing) encounter, the very first person the Buddha meetsafter his enlightenment, the naked ascetic Upaka, spurns the Buddha’s teaching. Whywas such an encounter—which must be considered somewhat embarrassing to the<strong>Buddhist</strong>s—included in the discourse?9) Many religious traditions suggest that leaving the household or domestic life <strong>for</strong> an ascetic ormonastic life is an important (if not necessary) step toward religious goals. The Buddhadescribes this as “going from home to homelessness.” Is leaving the domestic life criticalto making religious progress? If so, why?10) Are sensual pleasures really as dangerous as the Buddha seems to say they are? While allouthedonism may be an unjustifiable extreme, sensual pleasures seem to be an importantpart of human happiness. So how can the Buddha justify his emphasis on restraining thesenses <strong>and</strong> developing an “aloofness from sense pleasures?” What, then, of the arts(which often celebrate the pleasures of sense experience)?11) The higher states of experience recommended by the Buddha <strong>and</strong> several other traditions ofhis time (e.g., the four jhānas <strong>and</strong> the various planes) are the product of long <strong>and</strong> arduousstriving <strong>and</strong> so not immediately available to most people. Is there any reason, other thanthe authority of sages like the Buddha, to consider such accounts of higher states ofexperience plausible?12) The Buddha often personified evil by referring to Māra, the Evil One (a <strong>Buddhist</strong> “Satan”).Should Māra be considered in literal terms as a real being? Or is Māra better interpretedas a fictional being or a metaphor?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Two: Discourse to the Kālāmas (Kālāma Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Summarize the reputation of the Buddha as reported by the Kālāmas.2) What troubling issue, regarding the teachings of other recluses <strong>and</strong> Brahmins, did theKālāmas bring to the attention of the Buddha?3) What are the sources of knowledge/belief that are not recommended by the Buddha as goodreasons <strong>for</strong> accepting a certain doctrine or teaching? Why are these not recommended?4) What are the sources of knowledge/belief that are recommended by the Buddha as goodreasons <strong>for</strong> accepting a certain doctrine or teaching? Why are these recommended?5) What three underlying psychological factors (referred to as “defilements”) are at the root ofthose theories <strong>and</strong> doctrines that “are unwholesome, blameworthy, <strong>and</strong> reproached by thewise?”6) What three underlying psychological factors are at the root of those theories <strong>and</strong> doctrines that“are wholesome, not blameworthy, <strong>and</strong> commended by the wise?”7) What are the moral attributes of the noble disciple?8) What are the four com<strong>for</strong>ts of the noble disciple (i.e., as regards the noble disciple’s views onmoral conduct <strong>and</strong> the “after-world”)?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) The Kālāmas report coming in contact with a wide variety of teachers who make various,even contradictory claims. They want the Buddha to help them sort out which claimsthey should believe. Is this situation similar to the situation today where there are somany competing claims to truth (especially as regards important matters such asphilosophy <strong>and</strong> religion)? Is it appropriate to think that there is only one truth among allthe competing theories?2) Most religious traditions—<strong>and</strong> many cultural beliefs as well—are based on the very sourcesthat Buddha rejects, namely: tradition, report (personal authority), <strong>and</strong> the authority ofscriptures. Christianity <strong>and</strong> Islam, <strong>for</strong> example, are squarely based on the authority oftheir scriptures (the Bible, <strong>for</strong> Christians <strong>and</strong> the Koran, <strong>for</strong> Muslims). Is the Buddhacorrect in discarding these sources as a basis <strong>for</strong> belief?3) The Buddha recommends that the proper basis <strong>for</strong> belief is the sorting out of the variousclaims by one’s own experience or investigation (this is a version of the philosophicalposition called “empiricism”). But is this the proper basis <strong>for</strong> belief? Most religioustraditions <strong>and</strong> many philosophical systems (e.g., Plato’s philosophy) reject any <strong>for</strong>m ofempiricism as the final arbiter of truth <strong>and</strong> knowledge. Which view is right?4) What does the Buddha mean by saying that one should not accept a claim “by mere logic <strong>and</strong>inference?” Is that not part of the empirical method he is proposing <strong>for</strong> finding truth <strong>and</strong>grounding belief?

5) The tenfold <strong>for</strong>mula is supposed to explain the arising <strong>and</strong> ceasing of suffering without anymetaphysical commitments to a permanent Self—is that possible? Who is it, then, thatsuffers?6) The denial of a permanent Self is perhaps Buddhism’s most notable departure <strong>for</strong> otherreligious <strong>and</strong> philosophical traditions. Christians <strong>and</strong> Platonists believe in an immortalsoul; Hindus believe in the permanent ātman—but the <strong>Buddhist</strong> tradition denies theseviews of a permanent Self as pernicious lies. What arguments do the <strong>Buddhist</strong>s offer tosupport this position? How might a Christian or Hindu reply to the <strong>Buddhist</strong> analysis?What specific type of permanent Self do the various traditions declare(material/immaterial, limited/unlimited)?7) What depends on the view of a permanent Self or soul?8) Why would “feeling” be so closely associated with a person’s self? What are the Buddha’scounterarguments to such a view? Are his counterarguments effective?9) Why is it not proper to speculate about the existence of the Tathāgata after death? Should notthe Buddha make some commitment to the status of a Tathāgata after death? Is it not theproper function of a religious tradition to offer some answers (or even solace) on thematter of death?10) Is there any reasonable way to justify the Buddha’s claims about the “seven states ofconsciousness <strong>and</strong> the two planes” without experiencing these oneself? Must one acceptthese teachings on faith?11) Do other religious <strong>and</strong> philosophical traditions have “stages of liberation” like Buddhism?Do other traditions focus on psychological development in ways similar to the <strong>Buddhist</strong>path?12) In the early <strong>Buddhist</strong> tradition, the one who is liberated continues to dwell in this world.How is this different from the image of liberation in other religious <strong>and</strong> philosophicaltraditions? Is there any reason to think liberation can be achieved without removingoneself from this world (after all, even <strong>Buddhist</strong> see this world as a place fraught withsuffering <strong>and</strong> woe)?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Four: The Greater Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness(Mahāsatipahāna Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What does the fourfold foundation of mindfulness (sati) aim to achieve?2) What are the four foundations of mindfulness?3) What techniques of meditation are involved in the first foundation of mindfulness? Whichbodily activities are involved?4) What are the four elements that comprise the body?5) Summarize the techniques of meditation that relate to the cemetery.6) How does a bhikkhu live mindfully observing feeling as feeling?7) What are the mental phenomena relating to the five obstacles that a bhikkhu should observe soas to establish mindfulness?8) What are the mental phenomena relating to the five aggregates of grasping that a bhikkhushould observe so as to establish mindfulness?9) What are the mental phenomena relating to the six internal <strong>and</strong> external bases of sense that abhikkhu should observe so as to establish mindfulness?10) What are the mental phenomena relating to the seven factors of enlightenment that a bhikkhushould observe so as to establish mindfulness?11) Give a summary description of each of the Four Noble Truths.12) How does craving arise from the various sensory objects, sense faculties <strong>and</strong> modes ofsensory modes of consciousness?13) What result can be expected <strong>for</strong> one who develops these four foundations of mindfulness?How long must one develop the four foundations of mindfulness to achieve these results?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Is the development of mindfulness a useful tool <strong>for</strong> achieving religious goals? Is there aconnection between mindfulness <strong>and</strong> moral conduct as the Buddha suggests? Do otherreligious or philosophical traditions contain psychological or meditative practices similarto mindfulness in Buddhism?2) Is there any reason to believe that the development of mindfulness is effective in providingcontrol over one’s bodily or mental faculties?3) Why are breathing <strong>and</strong> focalization techniques recommended as the best means <strong>for</strong> achievingmindfulness? How do such techniques relate to more well known practices like yoga <strong>and</strong>Lamaze?4) The suggested cemetery meditations seem to be a grotesque, even macabre, way to view thebody. Are such negative images of the body warranted? What purpose might thesemeditations have?5) Do the meditative practices suggested <strong>for</strong> achieving mindfulness make a person aloof <strong>and</strong>disengaged from the world or more involved <strong>and</strong> engaged with the world?

6) What does mindfulness reveal regarding the nature of bodily <strong>and</strong> mental phenomena? Howdoes this relate to the Buddha’s teaching of dependent arising?7) The discourse gives one of the more detailed accounts of the Four Noble Truths found in thePāli Canon. Is the Buddha right that “suffering” (dukkha) is a pervasive feature of humanexistence (i.e., the First Noble Truth)? How should one underst<strong>and</strong> what the Buddhameans by “suffering,” <strong>for</strong>, surely, most people are not in constant physical pain? Shouldbirth, old age <strong>and</strong> death be considered “suffering?”8) Is selfish craving the main cause of suffering, as the Buddha explains in the Second NobleTruth?9) According to the Third Noble Truth, the cessation of craving involves “aversion” towards <strong>and</strong>“renunciation” of agreeable pleasant sensory experiences. Is this not an ascetic extreme(of the kind the Buddha himself rejected)? Are not pleasant sensory experiences amongthe proper aims of a person’s quest <strong>for</strong> happiness?10) Are the specific suggestions of the Noble Eightfold Path (the Fourth Noble Truth) areasonable way to end selfish craving (<strong>and</strong> thus suffering)? Is the Path truly the “middleway” the Buddha suggests or is it tipped towards the extreme of asceticism? How doesthe Path compare <strong>and</strong> contrast with ethical practices promoted in other philosophical <strong>and</strong>religious traditions?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Six: Discourse of the Honeyball (Madhupiika Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What does the Buddha say is his “teaching” (his “view”), in reply to Daapāni? How didDaapāni react?2) How does the Buddha explain to the bhikkhus the stopping of evil states without remainder?(Refer to the chain of “propensities.”)3) How does Mahākaccāna, elaborating on he Buddha’s statement, relate the modes of sensoryconsciousness to the arising of mentally proliferated perceptions <strong>and</strong> (obsessive) notionsthat assail a person?4) How does Mahākaccāna explain the tripartite pattern of sensory experience as regards thearising of contact (phassa)? (Note that none of the components of sense experience—neither the sense faculty, nor the object of sense, nor the mode of sensory consciousnessis a self-subsistent thing—each exists as such only in relationship with the other factors.Hence the explanation is a “functional” account that attempts to avoid giving anycomponent in sensory experience an ontologically independent status—as such a statuswould contradict the Buddha’s doctrine of dependent arising.)5) What is the situation when any of the three components of sensory experience is absent?6) Why is the discourse named after a honeyball?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) In this discourse, the Buddha explains that sensory experience is the root of craving <strong>and</strong> other<strong>for</strong>ms of moral corruption. Is the Buddha suggesting that a person should avoid sensoryexperiences altogether or just certain types of sensory experience?2) Is the Buddha’s functionalist account of experience in this discourse consistent with hisdoctrine of dependent arising (paiccasamuppāda)? Is it consistent with his view thatthere is no permanent Self (attā)?3) Historically, many philosophers have explained experience dualistically as an affair comprisedof ontologically distinct subjects (minds) <strong>and</strong> objects. The Buddha’s functionalistapproach to experience appears to ab<strong>and</strong>on such ontological distinctions. Whatphilosophical problems is the Buddha trying to avoid? Is such an account of experiencetenable?4) Does the Buddha’s account of how obsessive <strong>and</strong> unwholesome states arise in a person seemplausible? Who might object? Why?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Seven: Short <strong>Discourses</strong> from the Sayutta NikāyaDiscourse to Kaccāyana<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What are the two extremes toward which the world is inclined <strong>and</strong> the person with rightwisdom avoids?2) In regard to these two extremes, what does the Buddha teach?3) Lay out the full twelve-fold <strong>for</strong>mula <strong>for</strong> dependent arising (paiccasamuppāda) in <strong>for</strong>ward(arising) order. What does the twelve-fold <strong>for</strong>mula account <strong>for</strong>?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Is the Buddha right that the world is inclined toward the metaphysical extremes of absoluteexistence or non-existence? Give examples of the metaphysical doctrines of otherphilosophical or religious traditions.2) Is the Buddha’s “middle way,” his doctrine of dependent arising, a plausible alternative to thetwo metaphysical extremes? How might a Hindu or a Platonist argue against such a“middle way?”3) Is the Buddha right that avoiding such extreme metaphysical commitments is a critical steptoward ab<strong>and</strong>oning the belief in a permanent Self <strong>and</strong> suffering such a metaphysical viewengenders?4) Is it possible to find security or solace in a changing world without a belief that somewhere,on some level, there is a permanent reality?Discourse to the First Five Disciples<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What are the five c<strong>and</strong>idates <strong>for</strong> a permanent Self (attā) that the Buddha analyzes? (The fivec<strong>and</strong>idates <strong>for</strong> the Self are also referred to as the five aggregates that comprise a person inthe Buddha’s own doctrine.)2) What three reasons does the Buddha give that none of the five c<strong>and</strong>idates satisfy the criteria<strong>for</strong> a permanent Self?3) What should a person see as “not mine?”4) How should the learned disciple react to the five aggregates? What religious goal does thisachieve?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Is the Buddha’s argument that there cannot be a permanent Self, because there is nothingamong the constituents of a person that meets the criteria (namely, permanence, pure

<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) The Buddha declares the rather surprising view that the “all” amounts only to the six sensefaculties <strong>and</strong> their objects. Such an epistemological (empiricistic) rendering of the “all”contrasts sharply with the conception of the “all” in metaphysical terms that is thehallmark of most other philosophical <strong>and</strong> religious systems (e.g., the “all” = God, theuniverse, or Brahman). Why does the Buddha describe the “all” in this way? How mightother traditions criticize the Buddha’s view?2) What does the Buddha mean when he suggests that one should “ab<strong>and</strong>on” the various sensefaculties <strong>and</strong> their objects? Is such ab<strong>and</strong>onment desirable? Is it possible?3) Why does one need to underst<strong>and</strong> the “all” in order to destroy suffering?Feelings that Should be Seen <strong>and</strong> the Dart<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What are the three kinds of feeling (vedanā)?2) What should each kind of feeling be seen as?3) What is the result of seeing feeling rightly?4) How does the uninstructed, ordinary person experience feeling? What does the ordinaryperson not underst<strong>and</strong> about feeling?5) How does the instructed, noble disciple experience feeling? What does the noble discipleunderst<strong>and</strong> about feeling?6) How many feelings does the ordinary person feel? How many feelings does the noble disciplefeel?7) What is the instructed, noble disciple detached from?8) What is the difference between the instructed, noble disciple <strong>and</strong> the uninstructed ordinaryperson?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Should even pleasant feelings be seen as a cause of suffering?2) Why does the learned noble disciple feel only one feeling (a bodily one) when touched by anunpleasant feeling, while an uninstructed ordinary person feels two feelings (a bodily one<strong>and</strong> a mental one) when touched by an unpleasant feeling? What does this suggest aboutthe way an enlightened person lives in the world <strong>and</strong> deals with pains <strong>and</strong> otherunpleasant experiences?3) Is it possible to escape from all painful bodily feelings? Is it possible to escape from allpainful mental feelings?4) Can a person lived detached from feelings (of all three types: pleasant, painful <strong>and</strong> neutral)without becoming aloof <strong>and</strong> indifferent to the world? Can an enlightened person feelregret?

<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) <strong>Early</strong> Buddhism emphasizes that sensual pleasures are “obstructions” to living a religious <strong>and</strong>happy life. Is it reasonable to hold such a negative view of sensual pleasures (after all,most people act as if sensual pleasures are among life’s greatest joys)?2) What, if anything, is more valuable to a human life than sensual pleasures? If human beingsare no more than the complex animals that evolutionary biology suggests they are, is itnot reasonable to identify human “good” with the sensual pleasures that serve as guiding<strong>for</strong>ces in human biology?3) What does the parable of the raft imply about the status of the dhamma? Does the parablepurport to show that the dhamma is an instrumental, rather than an absolute, truth? Is thedhamma, like the raft, something to be ab<strong>and</strong>oned after reaching enlightenment? Is thedhamma itself ab<strong>and</strong>oned (as some say that an enlightened life is “beyond good <strong>and</strong> evil”<strong>and</strong> thus beyond all teachings) or is it only the selfish attachment to the dhamma that isab<strong>and</strong>oned (but one remains living in accord with the principles of the dhamma)?4) Does the parable of the raft suggest a significant difference between the way <strong>Buddhist</strong>s regardthe teachings of the Buddha <strong>and</strong> the way members of other religions regard the centraldoctrines of their religion?5) Why do people want to believe in a permanent Self?6) Is not the Buddha’s no-permanent-self doctrine likely to cause anxiety <strong>and</strong> pessimism in hisfollowers as they realize that such a doctrine flirts closely with the possibility of death asa total annihilation of the person? How can a <strong>Buddhist</strong> avoid nihilism as a result of theno-permanent-self doctrine (in fact, the Buddha himself relates in this discourse that hehas been accused of nihilism)?7) The Buddha thinks that dependence on speculative metaphysical views gives rise to sorrow,depression <strong>and</strong> despair. But is it not just the opposite, that without such beliefs there isnothing to hope <strong>for</strong> (hence the attraction of highly metaphysical systems of belief likeChristianity, Hinduism <strong>and</strong> Platonism)? For example, is it not better to believe the moreoptimistic view that there is a permanent self or soul that lives on—even though theremay be little empirical evidence <strong>for</strong> such a view—than to be a hard-headed empiricistlike the Buddha <strong>and</strong> perhaps fall into pessimism <strong>and</strong> nihilism?8) This discourse contains the Buddha’s specific arguments against the belief in a permanent Selfthat were raised in Chapter Seven. See the discussion questions keyed to the Discourseto the First Five Disciples.9) Is eliminating or ab<strong>and</strong>oning the six sense faculties <strong>and</strong> their objects a reasonable religiousgoal? How does such a process compare or contrast with the practices of other religioustraditions?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Twelve: Discourse to Pohapāda (Pohapāda Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What are the various views held by recluses <strong>and</strong> Brahmins about the cessation of higherconsciousness recounted by Pohapāda to the Buddha?2) Why does the Buddha reject outright the first of the views recounted by Pohapāda?3) What are the key attributes of a Tathāgata?4) Why does a householder go <strong>for</strong>th from home into homelessness (<strong>and</strong> so become a bhikkhu)?How does such a person train oneself?5) How is a bhikkhu perfected in moral conduct (sīla)? (Make a list of the more importantaspects of the bhikkhu’s moral activities.)6) How does a bhikkhu guard his sense faculties? Why does he do so? What does he achieve asa result?7) How does a bhikkhu practice mindfulness?8) With what is a bhikkhu satisfied?9) What unvirtuous psychological factors (called the “five hindrances”) does the bhikkhuab<strong>and</strong>on?10) What is the result of eliminating the five hindrances? (Include a summary of the four jhānas<strong>and</strong> the planes of infinite space, infinite consciousness, <strong>and</strong> no-thing.)11) How does a bhikkhu achieve step-by-step the cessation of perception? Is the summit ofperception one or many?12) Which arises first, perception or knowledge?13) What are the three c<strong>and</strong>idates <strong>for</strong> a permanent Self (attā), according to Pohapāda? Howdoes the Buddha demonstrate that none of these are identical with perceptions (<strong>and</strong> thusnone <strong>for</strong>m a permanent Self)?14) Why does the Buddha tell Pohapāda that it is difficult <strong>for</strong> someone like him to underst<strong>and</strong>the Buddha’s teaching on the relationship between perceptions <strong>and</strong> the self?15) What are the ten issues that the Buddha has left undeclared (avyākata)? Why are these leftundeclared by the Buddha?16) What does the Buddha declare? Why does he declare these matters?17) What speculative views about the afterlife are held by some recluses <strong>and</strong> Brahmins? Howdoes the Buddha show that such views are foolish? (Refer to the analogies the Buddhauses about a person being in love with the most beautiful girl in the country <strong>and</strong> theperson building a staircase <strong>for</strong> a mansion.)18) What are the three kinds of “acquired self?” What does the Buddha’s teaching (dhamma)achieve in regard to these three kinds of acquired self?19) Do the three kinds of acquired self exist simultaneously, according to the Buddha? What isthe proper way to speak of the acquired self in regard to past, future <strong>and</strong> present? How isthis similar to the products derived from cow’s milk?20) What do the terms used to refer to the acquired self actually refer to? (In other words, whatis the “ontological” status of the acquired self?)

<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Why does Pohapāda ask the Buddha his view of the “cessation of higher perception?” Howis this connected to living a religious or moral life?2) Is perception always conditioned, as the Buddha claims? If so, by what is it conditioned?How does this relate to the Buddha’s doctrine of dependent arising? Why does theBuddha say that certain perceptions arise <strong>and</strong> others cease through training?3) How is perception related to knowledge? Is the Buddha right to say that knowledge is alwaysdependent on perception? Does this make the Buddha an empiricist? If so, why type ofempiricism did he hold? Which (if any) Western philosophers hold an epistemologicalposition similar to the Buddha’s?4) The Buddha describes again in this discourse the process of “going <strong>for</strong>th” into a religious life.See discussion questions 9-11 keyed to Chapter Five.5) This discourse recounts the long sections on moral conduct that contain many specific (if notsomewhat unusual) references to proper <strong>and</strong> improper moral practices. What are theethical principles that appear to underlie these long lists of actions? What meta-ethicalposition does the Buddha seem to take based on these sections on moral conduct (e.g.,deontology, consequentialism, or virtue ethics)?6) In these lists of moral practices, the Buddha recommends against a number of actions thatmost people today would not regard as actions involving a moral issue (e.g., predictinglunar eclipses (astronomy!), poetry, making ointments <strong>for</strong> the eyes). How should acontemporary <strong>Buddhist</strong> view the Buddha’s pronouncements about such actions? Shoulda <strong>Buddhist</strong> stick to the letter of these statements or is it more important to live in the spiritof the ethical principles that underlie these lists of practices? Are the Buddha’sstatements to be seen as valid only in his historical context?7) The Buddha emphasizes here <strong>and</strong> in many other discourses the need to restrain the sensefaculties. Is the practice of restraint in regard to the sense faculties a critical componentin living a religious life? Does this <strong>for</strong>m an essential component in other religioustraditions?8) Is mindfulness a reasonable method <strong>for</strong> achieving restraint of the sense faculties?9) Almost all philosophical <strong>and</strong> religious traditions recognize the five obstacles as impedimentsto the good life or the religious life. But are the reasons <strong>for</strong> eliminating these obstaclessimilar or different among the various traditions?10) The Buddha uses a series of stock analogies to describe the destruction of the five obstacles.What are the meanings of the various analogies to the destruction of the five obstacles:paying off a debt, recovering from sickness, release from prison, release from slavery,<strong>and</strong> a wealthy person crossing safely through the wilderness?11) This discourse also gives an account of the four jhānas. See discussion question elevenkeyed to Chapter One.12) In this discourse, the Buddha emphasizes that religious development is a “step-by-step” orgradual process. Is enlightenment a gradual process or one that may occur suddenly to aperson (as many later Mahāyāna <strong>Buddhist</strong>s describe)?13) Is there a permanent Self (attā) or soul? Are the Buddha’s reasons <strong>for</strong> denying the existenceof a permanent Self convincing?

14) How might a Hindu, a Christian or a Platonist (all traditions that posit an immortal self orsoul) attempt to evade the Buddha’s arguments <strong>and</strong>, in turn, support their own views ofthe self?15) This discourse again raises the issue of the ten speculative views. See discussion questionsone <strong>and</strong> two keyed to Chapter Eight.16) Is the Buddha’s justification <strong>for</strong> refraining from the ten speculative views reasonable?17) In this discourse, the Buddha recounts his challenge to recluses <strong>and</strong> Brahmins to supporttheir speculative views regarding their belief that there awaits a blissful life after death.The Buddha’s criticism of such views seems to stem from his dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong> empiricalevidence that the recluses <strong>and</strong> Brahmins admit they do not have. But is the Buddha rightto insist on empirical evidence in such matters? Are not religious beliefs (e.g., the beliefin God, heaven, Brahman, etc.) precisely those beliefs <strong>for</strong> which one should not expect tohave empirical evidence? Is this not the place where “faith” enters in? What shouldcount as a proper justification or authority <strong>for</strong> such beliefs (e.g., scriptures, religiousteachers, mystical experiences, etc.)?18) The Buddha’s conception of a dependently arisen self is divided into three types of“acquired” self in the discourse. Is this view of the self sufficient to account <strong>for</strong> thecontinuity of personal identity that each person experiences? Does such a view of selfaccount <strong>for</strong> the personal or subjective experience of self-reflexive consciousness thateach human being experiences?19) Why should one ab<strong>and</strong>on the “acquired” selves? Is it the “acquired self” that should beab<strong>and</strong>oned or just the defiling mental states that typically attend the “acquired self” <strong>for</strong>the unenlightened person?20) The analogy between the “acquired selves” <strong>and</strong> the various states of dairy products suggestsa staunchly anti-essentialist <strong>and</strong> nominalist underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the relationship between theterms used to describe the self <strong>and</strong> the changing process that is the self (a process havingno permanent essence). How might a Platonist or a Hindu (champions of essentialism)attempt to refute the Buddha’s position?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Thirteen: Discourse on the Threefold Knowledge (Tevijja Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What is the nature of the dispute between Vāseha <strong>and</strong> Bhāradvāja?2) Explain the Buddha’s initial response to Vāseha’s question, that none of these Brahmins (ortheir teachers) have seen Brahmā face-to-face. How is this like the simile of the blindfollowing the blind?3) Explain the Buddha’s second objection—that these Brahmins <strong>and</strong> their teachers see the samesun <strong>and</strong> moon as others do. How is this like the simile of the man who claims to be inlove with the most beautiful girl in the country? How is this like the simile of the manbuilding a staircase <strong>for</strong> a mansion he knows nothing about?4) The Buddha offers several more similes/analogies to the situation of these Brahmins relatingto a person’s attempts to cross a river. Briefly summarize these.5) What are the five characteristics of sensual desire? Why are these considered “bonds” or“fetters” to spiritual achievement?6) What are the five obstacles? How do these hold a person back from spiritual goals?7) In what ways are Brahmins different from Brahmā, according to the Buddha, making unionwith Brahmā unlikely?8) In what ways is a bhikkhu who lives the holy life similar to Brahmā, according to the Buddha,making union with Brahmā likely?9) What are the most important elements of living the holy life, according to the Buddha?Include a description of the four highest <strong>Buddhist</strong> virtues.<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) The dispute between Vāseha <strong>and</strong> Bhāradvāja appears to assume that only one religiousteacher or one religious doctrine can be right. But is there only one path to salvation?Could religious truth be plural, as sometimes described by the analogy that there aremany paths that reach the top of a mountain?2) Is the Buddha right to question the religious claims of the Brahmin sages who have not seenBrahmā face-to-face? On what basis should religious teachers claim authority <strong>for</strong> theirdoctrines?3) The Buddha’s criticism of the Brahmin sages suggests a strong rebuke of the dogmatism in theBrahmin (Hindu) teachings. Is dogmatism justified in the case of religious beliefs?4) Knowledge of the three Vedas was at the center of the Hindu tradition at the time of theBuddha. Brahmins who possessed such profound, spiritual knowledge were thought tohave the keys to salvation. Many other religious traditions also place ultimatesoteriological importance on the knowledge of sacred texts—often construed as theprecise word of God. Is the knowledge <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing of sacred texts essential to

achieving religious goals? How should <strong>Buddhist</strong>s regard their own sacred texts? Doesknowledge of the Buddha’s discourses bring salvation, from a <strong>Buddhist</strong> point of view?5) The Buddha again criticizes the Brahmin’s religious claims because they lack empiricalevidence to support them. See question 17 keyed to Chapter Twelve.6) Would the dissimilarities between Brahmā <strong>and</strong> the Brahmins who possess the threefoldknowledge preclude a beatific union between them after death? Do the purportedsimilarities between the trained bhikkhu <strong>and</strong> Brahmā suggest the likelihood of theirunion?7) How is the Buddha’s conception of union with Brahmā radically different from the conceptionof such union held by the Brahmins who possess the threefold knowledge? Why did theBuddha suggest this new way of conceptualizing union with Brahmā? Why does theBuddha retain the notion of “union with Brahmā” at all?8) The four cardinal virtues (brahmavihāras) of Buddhism are: loving-kindness, compassion,sympathetic joy <strong>and</strong> equanimity. Why are these particular virtues singled out as crucialto eliminating suffering <strong>and</strong> achieving happiness?9) How do these cardinal virtues compare with the highest virtues taught by other philosophical<strong>and</strong> religious traditions?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Fourteen: Discourse to Assalāyana (Assalāyana Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What has the Buddha asserted regarding the four classes of society that has offended theBrahmins?2) What are the five reasons why Brahmins see themselves as the highest social class?3) The Buddha gives at least eight reasons why he thinks the Brahmin’s claim to be the highestsocial class is baseless. Summarize four of these reasons.4) The Buddha points out that Assalāyana keeps shifting his defense of the Brahmin claim toprecedence. How so? Why does Assalāyana’s last position agree with the Buddha’s ownposition? How is this different from the claims of the Brahmins to be the highest socialclass?5) What is the meaning of the parable the Buddha relates about the seven <strong>for</strong>est-dwellingBrahmins visited by the seer Asita Devala?6) How does the Buddha account <strong>for</strong> the (reproductive) conception of a human being?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Are there claims to class precedence in present-day society? If so, what is the basis <strong>for</strong> suchclaims? How do they compare with the claims made by the Brahmins in this discourse?2) On what basis should one accept the precedence of a certain class (e.g., based on birth,economic status, education)?3) Is the Buddha right to reject the claims of precedence in regard to social st<strong>and</strong>ing, but acceptprecedence based on moral/spiritual achievement?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Fifteen: The Lion’s Roar on the Wheel-turning Monarch(Cakkavattisīhanāda Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) What should be a bhikkhu’s guiding light <strong>and</strong> refuge?2) What are just kings called in this discourse?3) What are the key characteristics <strong>and</strong> duties of a “wheel-turning monarch?”4) Is the “sacred wheel-gem” something passed down by inheritance?5) What two characteristics of the people are affected by their moral degeneracy?6) Why does civilized society degenerate <strong>and</strong> eventually revive in kingdom described in thediscourse?7) What are the proper functions <strong>and</strong> responsibilities of the king (government) in regard to thepoor?8) By what principle should a king govern the people?9) How did the “wheel-turning” king conquer adjacent l<strong>and</strong>s? What moral precepts did hepreach to them?10) According to the discourse, how are moral <strong>and</strong> socio-economic conditions related?11) What does the king fail to do that brings the utopian society to an end <strong>and</strong> initiates thedownward spiral of society?12) What goes wrong with the king’s initial strategy <strong>for</strong> dealing with stealing?13) What was the unintended effect of the king’s institution of capital punishment <strong>for</strong> thieves?14) List the ten “bad deeds” referred to in section 18.15) Describe the lowest point in the degeneration of society (the “weapon-period”).16) How do the people put themselves back on the right track to civilized existence? List the ten“good deeds” referred to in section 22.17) What spiritual leader does the Buddha predict will come in the distant future when theutopian society is reestablished? How does this person relate or compare to the Buddhahimself?18) What does King Sakha do once the government infrastructure is rebuilt <strong>and</strong> the utopiansociety restored?19) Briefly describe the five virtues of the bhikkhu (life span, beauty, happiness, enjoyment, <strong>and</strong>strength).<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Is the story of the degeneration <strong>and</strong> regeneration of society to be taken literally? If not, is thestory best described as a “myth,” an “allegory” or a “parable?”2) What is the main message of the story of the degeneration <strong>and</strong> regeneration of society?3) Is the discourse correct in suggesting that the government is responsible <strong>for</strong> three things: thesafety of the people, the material welfare of the people, <strong>and</strong> the promotion of moral

conduct among the people? Do governments today see these three areas as the primaryresponsibilities of a good government? Is the Buddha promoting a <strong>for</strong>m of socialism?4) Is good government the foundation of the moral conduct of the people? Is it the responsibilityof political leaders to model moral behavior <strong>for</strong> the populace? Do bad governments havedeleterious effects on the moral well-being of the people? If so, how so?5) The discourse implies that the king’s implementation of capital punishment backfires—thatsuch violence breeds only more violence—is the <strong>Buddhist</strong> position on this plausible? Canthe threat of <strong>for</strong>ce or violence be used effectively to encourage lawful behavior amongcitizens?6) The spiral of social degeneration began when the king failed to provide money to the poor.Does this help explain the crime, violence, <strong>and</strong> immorality found in our world? Arepoverty <strong>and</strong> criminality related in the way the discourse suggests?7) Is the Buddha recommending monarchy as the best <strong>for</strong>m of government?8) What connection (if any) holds between the long story <strong>and</strong> the discussion of the five virtues ofthe bhikkhus at the end of the discourse?

<strong>Study</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Discourses</strong>Chapter Sixteen: Discourse to the Layman Sigāla (Sigālovāda Sutta)<strong>Study</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) Why did Sigāla pay homage to the four directions, the nadir <strong>and</strong> the zenith?2) What are the key differences between Sigāla’s practice of paying homage <strong>and</strong> that describedby the Buddha in reference to the noble disciple?3) What are the four defilements of action the noble disciple ab<strong>and</strong>ons?4) What are the four bases <strong>for</strong> evil actions?5) What are the six ways one might dissipate one’s wealth? Refer to some of the dangersassociated with each of these.6) What are the four types of non-friend who only appear to be friends? What are some of thekey reasons why such a non-friend is truly no friend?7) What are the four types of true friend? What are some of the key reasons why such friends aretrue friends?8) How does the Buddha correlate each of the four directions, the nadir <strong>and</strong> the zenith, withpersons to whom one should minister or pay homage?9) What are the five ways that a child should minister to parents? A student should minister toteachers? A person should minister to recluses <strong>and</strong> Brahmins?<strong>Discussion</strong> <strong>Questions</strong>1) This discourse is widely considered as an authoritative source of guidance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong>laypersons. Should there be one set of moral principles <strong>and</strong> practices <strong>for</strong> the bhikkhus<strong>and</strong> bhikkhunis <strong>and</strong> another set <strong>for</strong> lay-followers?2) The Buddha claimed explicitly that nibbāna is within the reach of laypersons, although theBuddha also made clear that the domestic life poses many obstacles to religious progress.But if laypersons <strong>and</strong> monastics alike can achieve enlightenment, what distinguishes thetwo paths? Why did the Buddha speak so disparagingly of domestic life?3) Given the obvious obstacles to religious progress posed by domestic life (the dem<strong>and</strong>s offamily, job, etc.), can a layperson be a serious <strong>Buddhist</strong>? If arahantship is achieved onlythrough the intense mental training <strong>and</strong> profound insight that uproots the mentaldefilements that lead to unwholesome actions (<strong>and</strong> to suffering), should not anyonetaking the <strong>Buddhist</strong> path leave the domestic life?4) What meta-ethical theory does the Buddha draw upon in his ethical teachings to laypersons?5) For a <strong>Buddhist</strong> layperson, friendship is among the virtues most exalted by the Buddha. Whatare the attributes of a true friend?6) Is friendship crucial to living a meaningful life? Does friendship have spiritual or religiousmeaning? Does friendship play an important role in other philosophical or religioustraditions?

7) How should a contemporary <strong>Buddhist</strong> take the <strong>Buddhist</strong>’s statements that a householdershould avoid festivals, dancing, <strong>and</strong> singing? Are these activities—that are so much apart of everyday life today—truly dangerous?8) Why did the Buddha change the meaning of paying homage to the six directions from a rite ofprayer to the mystical powers represented by the directions to a rather comprehensive listof ethical <strong>and</strong> social responsibilities (to parents, teachers, spouse <strong>and</strong> children, friends,servants, <strong>and</strong> religious teachers)?9) For those who minister to the persons represented by the six directions, the Buddha describesa response—reciprocal actions—returned to the one who ministers by those ministeredto. What is the Buddha suggesting about the social <strong>and</strong> ethical relationships amonglaypersons?