View - UNAIR | E-Book Collection

View - UNAIR | E-Book Collection

View - UNAIR | E-Book Collection

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

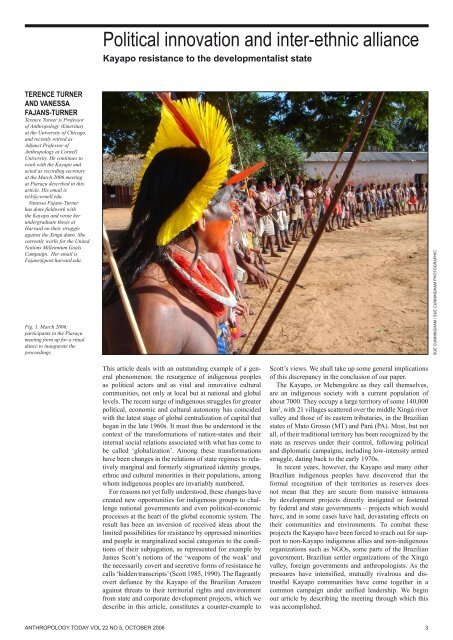

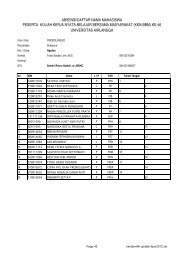

Political innovation and inter-ethnic allianceKayapo resistance to the developmentalist stateTerence Turnerand VanessaFajans-TurnerTerence Turner is Professorof Anthropology (Emeritus)at the University of Chicago,and recently retired asAdjunct Professor ofAnthropology at CornellUniversity. He continues towork with the Kayapo andacted as recording secretaryat the March 2006 meetingat Piaraçu described in thisarticle. His email istst3@cornell.edu.Vanessa Fajans-Turnerhas done fieldwork withthe Kayapo and wrote herundergraduate thesis atHarvard on their struggleagainst the Xingú dams. Shecurrently works for the UnitedNations Millennium GoalsCampaign. Her email isFajans@post.harvard.edu.Fig. 1. March 2006:participants in the Piaraçumeeting form up for a ritualdance to inaugurate theproceedings.Sue Cunningham / Sue Cunningham PhotographicThis article deals with an outstanding example of a generalphenomenon: the resurgence of indigenous peoplesas political actors and as vital and innovative culturalcommunities, not only at local but at national and globallevels. The recent surge of indigenous struggles for greaterpolitical, economic and cultural autonomy has coincidedwith the latest stage of global centralization of capital thatbegan in the late 1960s. It must thus be understood in thecontext of the transformations of nation-states and theirinternal social relations associated with what has come tobe called ‘globalization’. Among these transformationshave been changes in the relations of state regimes to relativelymarginal and formerly stigmatized identity groups,ethnic and cultural minorities in their populations, amongwhom indigenous peoples are invariably numbered.For reasons not yet fully understood, these changes havecreated new opportunities for indigenous groups to challengenational governments and even political-economicprocesses at the heart of the global economic system. Theresult has been an inversion of received ideas about thelimited possibilities for resistance by oppressed minoritiesand people in marginalized social categories to the conditionsof their subjugation, as represented for example byJames Scott’s notions of the ‘weapons of the weak’ andthe necessarily covert and secretive forms of resistance hecalls ‘hidden transcripts’ (Scott 1985, 1990). The flagrantlyovert defiance by the Kayapo of the Brazilian Amazonagainst threats to their territorial rights and environmentfrom state and corporate development projects, which wedescribe in this article, constitutes a counter-example toScott’s views. We shall take up some general implicationsof this discrepancy in the conclusion of our paper.The Kayapo, or Mebengokre as they call themselves,are an indigenous society with a current population ofabout 7000. They occupy a large territory of some 140,000km 2 , with 21 villages scattered over the middle Xingú rivervalley and those of its eastern tributaries, in the Brazilianstates of Mato Grosso (MT) and Pará (PA). Most, but notall, of their traditional territory has been recognized by thestate as reserves under their control, following politicaland diplomatic campaigns, including low-intensity armedstruggle, dating back to the early 1970s.In recent years, however, the Kayapo and many otherBrazilian indigenous peoples have discovered that theformal recognition of their territories as reserves doesnot mean that they are secure from massive intrusionsby development projects directly instigated or fosteredby federal and state governments – projects which wouldhave, and in some cases have had, devastating effects ontheir communities and environments. To combat theseprojects the Kayapo have been forced to reach out for supportto non-Kayapo indigenous allies and non-indigenousorganizations such as NGOs, some parts of the Braziliangovernment, Brazilian settler organizations of the Xingúvalley, foreign governments and anthropologists. As thepressures have intensified, mutually rivalrous and distrustfulKayapo communities have come together in acommon campaign under unified leadership. We beginour article by describing the meeting through which thiswas accomplished.ANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006 3

Fig. 2. The war dance isperformed during an intervalin the speeches at the Piaraçumeeting in March 2006.Frequent breaks for collectivedance performances werean integral part of theproceedings, serving toexpress the solidarity of therepresentatives of differentcommunities and theirsupport for the speakers.Sue Cunningham / Sue Cunningham PhotographicUniting against the common enemyTwo hundred representatives of 19 of the 21 Kayapo communitiesmet for five days in the village of Piaraçu on theXingú River between 28 March and 1 April 2006 (the twoabsent communities had wanted to attend but were unableto find the money for travel expenses). The main subject ofdiscussion was the need to present a common front againstthe Brazilian government’s attempts to revive its perennialproject to build hydroelectric dams at Belo Monte and fourother sites on the Xingú River and its main tributary, theIrirí. The meeting was the culmination of years of organizationand alliance-building by the Kayapo, under theleadership of Megaron Txukarramãe, a Kayapo from thevillage of Mentuktire who is also director of the regionaloffice of FUNAI, the Brazilian agency for Indian affairsin Mato Grosso. The objective of this protracted Kayapocampaign has been to put together a united front of all thepeoples of the Xingú Valley, some 25 distinct indigenousgroups and organizations of national Brazilian settlers,against the proposed Xingú dams and other environmentallydestructive development projects (Fajans-Turner andTurner 2005).The Kayapo and their allies insist that they are notopposed to development as such, but rather to the approachto development perennially favoured by Brazilian governmentplanners. This typically stresses big, capital-intensiveinfrastructure projects, such as giant hydroelectric damsand highways driven through fragile ecosystems in violationof the legal and human rights of local populations,without regard to the environmental damage and socialdisruption they cause. This policy and its associated ideologyhas come to be called ‘developmentalism’ in contrastto other approaches to development that emphasizesmaller-scale, local labour-intensive inputs and environmentallysustainable production.The first step in the Kayapo campaign to build an effectivemovement of resistance to the Xingú dams and otherdevelopmentalist projects in their area had been to mendtheir relations with the other indigenous groups of theXingú valley. Mutual antagonism and distrust had becomeparticularly intense with the Upper Xinguano indigenouscommunities of the National Park of the Xingú. Kayapoleaders dealt with these tensions by inviting representativesof these groups to attend a meeting in November 2003, atthe Kayapo village of Piaraçu, located on the east bankof the Xingú by the northern border of the park. At themeeting Megaron and other Kayapo speakers successfullypersuaded the representatives of the other groups that thethreat posed by the dams and pollution from encroachingcattle ranches and soya plantations to the river on whichthey all depended made a common struggle to save theXingú essential. Even the new president of FUNAI, DrMércio Pereira Gomes, made an appearance at the meetingto give his blessing to the new era of peaceful relationsamong the indigenous peoples of the Xingú, although hecarefully avoided taking the Indians’ side against the damsand other developmentalist projects that threatened theirhome territories (Fajans-Turner 2003, Fajans-Turner andTurner 2005).One intractable problem remained: three of the largestKayapo villages from the eastern part of Kayapo territoryhad boycotted the meeting because of their longstandingrivalry with the western Kayapo communitiesunder Megaron’s leadership. Before the Kayapo couldhope to lead a united indigenous coalition to save theXingú, they had to overcome their own internal divisions.In December 2005, Megaron made a personal tour of theKayapo villages, including those that had not attended the2003 meeting. The immediate objective of the visits wasto persuade all the communities to send representatives to ANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006

TERENCE TURNERFig. 3. A peacefulconversation between futureantagonists: Mércio Gomes,shortly after his appointmentas president of FUNAI, theBrazilian agency for IndianAffairs, chats with Kayapoleaders Ropni and Megaronat a meeting held at Piaraçuin 2003. Gomes’ advocacyof the Lula government’senvironmentally and sociallydestructive infrastructureprojects in the Amazon hadnot yet become evident to theIndians.another meeting at Piaraçu, this one to be limited exclusivelyto Kayapo and their close neighbours and allies,the Panara and some Juruna who were currently living atPiaraçu with the Kayapo.Megaron’s tour was a complete success, resulting inthe second Piaraçu meeting in March 2006. This meetingachieved all that Megaron had hoped. The hitherto recalcitranteastern villages attended and joined with the othercommunities in a unanimous consensus to begin organizinga movement of all the ‘peoples of the Xingú’ againstthe dams. Over 100 speakers at the week-long meetingrejected construction of the dams, alleging that they wouldhave catastrophic effects on the riverine ecosystem, andwould flood large areas of indigenous territory. Manyspeakers introduced their remarks by singing their personal‘anger-songs’, customarily sung when going into battle,and some warned that they would go to war if necessary tostop construction of the Belo Monte dam, planned as thefirst of the series. They also denounced Brazilian PresidentLuis Inacio Lula da Silva and Eletronorte, the governmentagency responsible for the dams, for failing to disclose thetrue scope of the project. The government has representedit for public consumption as involving a single dam at BeloMonte, whereas in fact it envisages four additional damswhich would be essential for Belo Monte to operate withmaximum efficiency (Switkes 2005). Speakers furtherdenounced Lula and Eletronorte for violating Article 231of the Brazilian constitution, which requires that developmentprojects planned for indigenous areas should bedebated by the National Congress, with the participationof representatives from the affected communities. NeitherEletronorte nor governmental proponents of the dams hadmade any attempt to comply with this requirement.An independent legal challenge to this constitutionalviolation led to a dramatic moment at the Piaraçu meeting.Under pressure from indigenous activists, the MinistérioPúblico (the office of the public prosecutor in the Ministryof Justice, the equivalent of an Attorney General), hadinstigated federal court proceedings against Eletronorteto halt all work on the dams (including planning) whilethe government remained in violation of the constitution.In the midst of the Kayapo meeting, on 30 March, newsarrived that a federal judge in the nearby city of Altamirahad found for the plaintiffs in this suit, and issued an injunctionhalting all work on the dams. Many at the meetingfelt that the mobilization of the Kayapo for the renewedstruggle against the dams had played a part in influencingthe judge’s verdict. Whether or not this was true, it contributedto the general feeling of those at the meeting thatthey were on a roll and could win despite the odds. In Maythe judge’s decision was sustained on appeal by a federaljudge in Brasília, with the Ministério Público acting forthe plaintiffs. The entire Xingú dam scheme may well nowhave to be abandoned.Forging an alliance with the whitesImmediately following the successful conclusion of the2006 Piaraçu meeting, Megaron initiated the next andbiggest step in the Kayapo alliance-building process: contactingthe leaders of regional Brazilian settler organizationsto persuade them to join with the Kayapo and theirindigenous allies in the campaign to save the Xingú fromthe dams and pollution. He proposed that Indians and settlersshould jointly organize a great rally in Altamira inopposition to the dams and other environmentally destructivedevelopments, including logging, mining and riverpollution. Brazilian settlers have historically tended tobe hostile or at best indifferent to Indians, but they havefor their own reasons become opposed to the constructionof the proposed dams and the pollution of the river.ANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006 5

Fig. 4. Kayapo men danceat the meeting of all Kayapovillages held in March 2006.TERENCE TURNERThe response of the leaders of settler organizations toMegaron’s overtures was enthusiastically positive.As Megaron said in the Declaration of Piaraçu, circulatedto NGOs and the media immediately following thePiaraçu meeting:We Mebengokre are aware that the problems that threaten thelives of our communities in the Xingú Valley also threatenother peoples, both indigenous and Brazilian, who live in thevalley. The solution of these problems, and thus the effectiveprotection of our river and our forest, lies in a common struggle,which we share with all the peoples of the Xingú Valley.Eighteen months ago, we met together with the other indigenouspeoples of the Upper, Middle and Lower Xingú in Piaraçuto forge a common front against these threats. Now, followingupon the successful conclusion of the meeting of all of ourown communities, we are entering upon the next stage of ourstruggle, contacting organizations of national Brazilian settlersof the Lower Xingú and the Transamazonica [highway] to forman alliance of all the peoples of the Valley of the Xingú to saveour river from the dams, pollution, and all kinds of destructivedevelopment, and to promote alternative forms of productionbased on the powers of local communities using sustainableresources.We call on all the inhabitants of the Xingú Valley to join withus in a great rally at Altamira against the Belo Monte dam andthe other dams that Eletronorte wants to build throughout ourvalley, and for the protection and development of our own productivepowers, our cultures and communities. (Txukarramãe2006; English translation T. Turner)Collective effervescence and the creation ofritualThe March Piaraçu meeting was a historic achievement forthe Kayapo: the first time that all Kayapo communities hadunited for a common cause under a common leadership.There was a feeling of excitement among those presentthat they were being part of something new and important– the emergence of a united Kayapo political community.This feeling was expressed in Kayapo cultural termsthrough the performance of a new ceremony, composedfor the occasion, at the close of the meeting. In this ritualyoung, recently proclaimed chiefs (benhadjuòrò) handedseedlings from the fruit-bearing piki tree to senior chiefs,elder statesmen whose pan-communal authority is recognizedby all Kayapo. The elder chiefs proceeded to plantthe seedlings, and while standing over them, exhorted theyounger chiefs to step into the roles that they, the elders,were about to vacate, to assure the continuity of Kayapoculture (kukràdjà) and social order.The ritual dramatized the meeting’s call for the collectivedefence and renewal of Kayapo society as a politicalcommunity. Notably, two of the four senior chiefs whotook part in the ritual chose as their partners young chiefsfrom villages other than their own, a departure from normalKayapo practice in which succession to the chiefly officeis through proclamation by a senior chief of the samecommunity. This gesture (which surprised some of thosepresent, including some who had shared in creating thenew ritual during the meeting) expressed the senior chiefs’understanding that through this meeting, the Kayapo hadconstituted themselves as a political community at a levelhigher than that of individual villages. At the same time,the ritual dramatized the dual significance of the Kayaporesistance to the dams as both protection of their territoryand, more fundamentally, a defence of their way of life.The wider context: Development at any cost vs.Amazonian rivers, forests and peoplesThe consolidation of a political movement integratingall the Kayapo communities in alliance with the otherindigenous groups and Brazilian settler movements of theXingú valley was both motivated and threatened by ominousdevelopments in the policies of the government ofPresident Lula da Silva and the state government of MatoGrosso. By the time of the Piaraçu meeting of February-March 2006 it had become clear that the Lula governmenthad adopted a developmentalist programme of promotingbig capital-intensive infrastructural projects, such ashydroelectric dams and the paving of interstate roads likethe Cuiabá-Santarem highway (BR-163), at the expense ofenvironmental, social and human rights concerns. ANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006

TERENCE TURNERFig. 5. The piki tree seedlingceremony celebrated at theclose of the Piaraçu meetingin March 2006, expressingthe creation of a unitedKayapo political community.The seedlings (two arevisible, behind the speaker’shand and below the videocamera) have been planted byolder chiefs, who exhort theyounger chiefs facing themto continue their struggleto defend the whole Kayapopeople. The ceremony isbeing recorded by a youngKayapo video cameraman..These projects are key elements in the federal government’sIMF-inspired strategy of increasing exports to payoff Brazil’s foreign debt. In the concrete forms of the Xingúdam projects and the proposal to pave BR-163 to enablethe transportation of the huge soya, rice and maize cropsof Mato Grosso’s burgeoning agribusiness economy to theports of Santarem and Belem, these policies were alreadycasting long shadows over the Kayapo homeland. In themonths following the Piaraçu meeting, however, a seriesof further events served both to highlight and to intensifythe threats from these projects and the collateral effectsof the more general policy orientation of the national andstate governments that gave rise to them.By 2005 it had become evident that the demarcation ofindigenous territories as reserves by the National IndianFoundation, opposed by local landholders and developmentalistinterests alike, had virtually come to a halt (over200 indigenous territories remained undemarcated). TheLula government, represented by Mércio Gomes, presidentof FUNAI, appeared to have put the protection ofindigenous lands on hold in an effort to accommodatethese interests.For the Kayapo and most other indigenous groups, not tomention numerous NGOs, anthropologists and journalists,Gomes’ leadership of FUNAI had become identified withLula’s policy for developing Amazonia without regardfor constitutional and legal safeguards of indigenousand environmental rights. Stung by criticism from thesesources, Gomes gave an interview to Reuters news agencyin January 2006 defending FUNAI’s general record butadding the startling assertion, for one in his position, thatthe Indians’ demand for the demarcation of their land asreserves ‘was going beyond acceptable limits’, and suggestingthat the Supreme Court should consider imposinga cap on the proportion of the national territory that can beallotted to Indian reserves (MS 13/01/06; Estado de SãoPaulo, Section A:4, 13/01/06).This overt avowal of what many had come to suspectwas the real attitude behind the government’s Indianpolicy caused a storm of protest among indigenousgroups and NGOs supporting them. The Kayapo calleda meeting of 23 of their leaders and sent off a fiery protestto Lula, which called for a general change of policytowards Indians and the dismissal of Gomes as presidentof FUNAI (MS 30/01/06; Carmen Figueiredo, personalcommunication).The road to Santarem is paved withquestionable intentionsMeanwhile, in what began as a separate dispute over thesocial and environmental effects of development projects,the federal government’s attempt to evade its own lawthat calls for Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA)as prerequisites for licensing projects such as the pavingof BR-163 led to a renewed crisis with the Kayapo. TheMinistry of Transport and the Ministry of the Environmentbegan well enough in mid-2005 by holding two legallyprescribed public hearings in the Xingú valley for allgroups who would be affected by the road project. Theywere invited to present their views on the measures thatshould be taken to protect their rights and interests fromthe influx of construction crews, settlers and deforestationthat the road improvement would bring.Testimony at such hearings is supposed to be taken intoaccount in the preparation of the EIA, and thus incorporatedinto the final design and operation of the project.The Kayapo sent delegations to both hearings that madedetailed submissions. Their statements did not oppose thepaving of the road in itself, but called for it to be accompaniedby policing of the boundaries of the Kayapo andPanara reserves that lie close to the road, the demarcationof still undemarcated territories father to the north,compensation for environmental damage, and continuedconsultation with the Indians on dealing with the socialproblems certain to arise from increased road traffic andthe influx of settlers. After these hearings, nothing washeard about the paving project for several months.In December 2005, however, the government instituteresponsible for the protection of the Amazon, IBAMA,quietly granted a preliminary licence to the Ministry ofANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006

TERENCE URNERFig. 6. Kayapo chiefs signletters at a meeting at theFUNAI office in Colider,Mato Grosso, on 26 July2006. Front left to right:Kokoreti of Mekranoti,Ropni of Mentuktire, andMegaron Txukarramãe,regional FUNAI director.One letter was to PresidentLula, protesting against theillegality of his government’sattempt to circumventBrazilian laws in goingahead with the road pavingproject without the requiredenvironmental impactevaluation; another was tothe World Bank, urging it notto lend money to support theillegal project.Transport to proceed with plans for the paving of BR-163. This was irregular, since the Environmental ImpactAssessment normally required for such a licence had notyet been completed. The delay had been caused by disagreementsbetween the Ministry of the Environment andits agency, IBAMA, and the Ministry of Transport over theterms of the EIA.After six months the dispute was finally ‘solved’ bythe Minister of the Environment, Marina Silva, who inearly June produced a new ‘Plan for a sustainable BR-163’ designed to substitute for the legally required EIAand thus allow the licence granted six months earlier tobe activated (MS 06/06/06; 29/06/06). The plan containedprovisions for protected forest zones beside the road buttook no account of the proposals by the Kayapo for thedemarcation and police protection of indigenous communitieslocated near the road.This bureaucratic manoeuvre was completed withoutconsulting the Kayapo or any of the other indigenousor regional groups who had faithfully attended the hearingsfor the EIA and contributed their critical inputs (MS06/06/06). The result was triumphantly announced byLula in a speech on 6 June, followed a month later by ashort report in the official Gazette of Mato Grosso that thelicence had been issued and paving would proceed withoutreference to the legally required EIA (AA 22/12/05; MS06/06/06, 12/06/06; A Gazeta de Cuiaba 2006).The (paved) road shall not pass!When this came to the notice of the Kayapo, they werefurious. They felt that they had been betrayed by the government’shearings for the EIA, which they now saw ashaving been a ruse to distract them while the governmentsecretly went ahead with its plans to proceed with theproject without regard for the environmental and socialprotections, to say nothing of the consultations with themand other indigenous groups of the area, required by itsown laws. Kayapo and Panara leaders from the Xingúvalley met in the second week of July and agreed to takeimmediate action. They wrote to Lula denouncing his government’sviolation of Brazilian law and human rights, andto the president of the World Bank urging him not to granta loan for the road-paving project. A third letter went to theAttorney General of Brazil, calling upon him to enforcethe law and vowing to prevent the road from being paveduntil the government decided to comply with its own lawscovering licensing and EIAs.Then, making good on their promise, they sent a partyto blockade BR-163. For good measure, they also cut BR-80, the federal highway that serves as their boundary withthe National Park of the Xingú to the south, by sequesteringthe ferry that carries road traffic across the Xingú.They maintained the closure of both roads for four days,from 22 to 26 July, which was how long it took the federalgovernment and the state government of Mato Grossoto agree to the Kayapo’s condition for calling off theblockade. This was to send high-level representatives toa meeting with Kayapo leaders to discuss the restitutionof the environmental and social protections demanded bythe Kayapo and others in the public hearings for the EIA(Megaron Txukarramãe, personal communication; MS25-27/07/06).The meeting was held on 26 July at the Kayapo-controlledFUNAI headquarters in Colider, Mato Grosso. After sittingthrough a day of harangues by Kayapo leaders interspersedwith periodic eruptions of chanting and dancing byabout 100 or so Kayapo and Indians from other groups thathad participated in the roadblock alongside the Kayapo,the government representatives promised to produce arevised version of the road paving project incorporatingthe Kayapo demands within 30 days. This was the graceperiod granted by the Kayapo before the blockade of theroads would be renewed if no response were forthcoming(Sue Cunningham, personal communication). ANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006

TERENCE TURNERFig. 7. Chief Ropni haranguesBrazilian federal and stategovernment representativesat a meeting on 26 July, overthe Brazilian government’sfailure to comply withenvironmental laws relatingto the paving of the Cuiaba-Santarem highway.AA (Amazon Alliance) 2006.Website of the AmazonAlliance for indigenousand traditional peoples ofthe Amazon basin. http://www.amazonalliance.org;consulted 10 August 2006.A Gazeta de Cuiaba 2006.Gazette of the state of MatoGrosso, 4 July.AM (Amazonia) 2006. http://www.amazonia.org.br;consulted 10 June.Fajans-Turner, Vanessa 2004.‘Developing alternativesto “development”: Theinterethnic resistancemovement of the peoplesof the Xingú’. BA thesispresented to the HarvardCommittee on the Degreein Social Studies. HarvardUniversity, Cambridge,Mass.— and Turner, Terence 2005.Interethnic alliances amongindigenous and Brazilianpeoples of the Xingú.Anthropology News 46(3):27, 31.Keck, Margaret E. and Sikkink,Kathryn 1998. Activistsbeyond borders: Advocacynetworks in internationalpolitics. Ithaca: CornellUniversity Press.StandoffAfter the Brazilian representatives left, the Kayapo leadersthemselves departed for Brasilia, where on or about 5August they proceeded to picket the FUNAI head offices,demanding the immediate dismissal of president Gomesand his replacement with an Indian (MS 18/08/06). TheKayapo were joined by the equally militant Xavantenation, and the Amazonian Indian Federation COIABissued a fresh manifesto calling for Gomes’ dismissal. TheCOIAB text was largely based on the Kayapo letter to Lulasent from the Colider meeting a few weeks earlier, andwas clearly intended to support the Kayapo action (MS11/08/06, 18/08/06)Gomes succeeded in avoiding a showdown with theKayapo and kept his job, but his authority was weakenedby the public defiance and criticism of the Kayapo andthe other indigenous groups who supported them. As forBR-163, the Ministry of Transportation waited until theend of the 30-day period the Kayapo had set for them toproduce their revision of the paving project. Warned thatthe Kayapo were preparing to renew their roadblock, however,the Ministry called in Carmen Figueiredo, an expertfrom FUNAI who had been working closely with theKayapo on the road situation, and invited her to rewritethe relevant provisions of the project, incorporating theKayapo demands.As of this writing, it thus appears that the Kayapo havewon their battle to make the state fulfil its legal obligationsto protect their social and environmental rights in carryingout its BR-163 project. In the process they have performedan important service for all Amazonian peoples by publicizingthe prevailing pattern of government malfeasanceand evasion of legally mandated environmental protectionsin the construction and improvement of roads in theregion (Carmen Figueiredo, personal communication).As if to emphasize further the interdependence of theseissues with the Lula government’s developmentalist program,on 15 August, some 10 days after the start of theKayapo picketing of FUNAI, Lula made a speech vowingthat the Belo Monte dam, as well as others on the RioMadeira, would be built. He made no mention of the judicialinjunction now in effect against all further work onBelo Monte, or the views and rights of the indigenous andBrazilian settler communities of the Xingú valley, or thenumerous expert warnings of the environmental and economicdevastation the dams would cause (AM 16/08/06,Switkes 2005).The sources of Kayapo powers of resistanceIt is against this developmentalist climate of opinion inthe Lula government and its disregard for Brazilian law,as well as human rights and environmental values, that theKayapo have taken their stand. Although few in numberand only marginally integrated into the national society,culture and economy, they have been able to make themselvesthe centre of a wide and ethnically diverse networkof alliances with Amazonian peoples, including both indigenousand national Brazilian communities, and to attractsupport from an equally diverse assortment of groups fromnational and international civil society. They have beenable to build this network by evoking the common interestsof all these groups in preserving the human and environmentalvalues which Brazilian governments, in theirpursuit of developmentalist policies, have been preparedto sacrifice.Behind the national and state governments’ obsessiveadvocacy of environmentally destructive mega-projects,of course, has been the relentless pressure of the globaleconomy and its organs the IMF, international developmentbanks and the WTO, which utilize Brazil’s largeforeign debt as leverage to compel adoption of capitalintensivedevelopmentalist economic policies.While boldly and effectively organizing resistance togovernment projects, however, the Kayapo have cannilyANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006 9

Fig. 8. Kayapo blockade ofCuiaba-Santarem highway,22-26 July 2006. A warriorguards a barricade across theCuiaba-Santarem highway. Thebanner across the barricadebears the message, ‘Why won’tyou listen to us? Kayapo,Panara, Terena, Kayabiand Apiaca Indians demandtheir rights!’. Note stalledtraffic behind the barrier. TheKayapo provisionally liftedthe blockade when federaland state governments agreedto send representatives tomeet with them and receivetheir demands that legalmeasures designed to limitthe environmental and socialimpact of development on localpopulations be enforced.MS (ManchetesSocioambientais) 2006.Website of the InstitutoSocio-Ambiental, São Paulo.http://www.socioambiental.org; consulted July-August2006.Scott, J. 1985. Weapons ofresistance: Everyday formsof peasant resistance. NewHaven: Yale UniversityPress.— 1990. Domination and thearts of resistance: Hiddentranscripts. New Haven: YaleUniversity Press.Switkes, G. (ed.) 2005.Tenotã-mõ: Alertas sobre asconsequencias dos projetoshidrelétricos no rio Xingú.São Paulo: InternationalRivers Network.Turner, T. 1991. Representing,resisting, rethinking:Historical transformationsof Kayapo cultureand anthropologicalconsciousness. In: Stocking,G. (ed.) Post-colonialsituations: The history ofanthropology, vol. 7, pp.285-313. Madison, WI:University of WisconsinPress.— 1992. Defiant images: TheKayapo appropriation ofvideo. Anthropology Today8(6): 5-15.— 2003. Class projects,social consciousness,and the contradictions of‘globalization’. In Friedman,J. (ed.) Violence, the stateand globalization, pp. 35-66.New York: Altamira.— 2004. Anthropologicalactivism, indigenous peoplesand globalization. In:Nagengast, C. and Velez-Ibañez, C. (eds) Humanrights, power and difference:The scholar as activist,pp. 193-207.OklahomaCity: Society for AppliedAnthropology.Txukarramãe, M. 2006.‘Declaração da reunião dopovo Mebengokre Kayapo,Piaraçu, MT 28 Março-1 Avril 2006’ (Englishtranslation by T. Turner:‘Declaration of the meetingof the Mebengokre Kayapoat Piaraçu, Mato Grosso,March 28-April 1, 2006’).managed to present themselves as defenders of Brazilianlaw against Brazilian national and state governments withrogue developmentalist agendas that flagrantly violatestanding Brazilian legislation for the protection of indigenouspeoples’ territorial and human rights and environmentalvalues. In the process they have managed to gain thesupport of significant sectors of Brazilian political opinionand state apparatuses, including important elements of thelegal and judicial establishments, some government ministriesand elected members of Congress, including agentsof FUNAI itself.Kayapo leaders like Megaron have even been able togain appointments to strategic regional posts within theadministrative structure of FUNAI. In contrast to Scott’sscenario of ‘weapons of the weak’ to which we alludedat the beginning of this article, in short, the state doesnot confront the Kayapo as a monolithic entity with aneffective monopoly of political- economic and ideologicalhegemony. On the contrary, it is a heterogeneous collectionof actors and agencies, many with programmes oftheir own that are to varying degrees opposed to the developmentalistpolicies of the head of state. The Kayapo, aswe have seen, have been able to co-opt some of these discordantstate powers as ‘weapons’ in their own struggleswith federal and state governments.In a similar way, the Kayapo have managed to attractsignificant support from new domestic and internationalsocial movements (NSMs) and non-governmental organizations(NGOs). The growth of these essentially middleclassmovements committed to universal values andcauses such as human rights and environmentalism, oftenopposed to the interests and projects of globalized capital,has been a prominent feature of the social dynamics ofglobalization.The Kayapo, with some help from anthropologists andNGO representatives, quickly understood that their strugglesfor territorial and cultural rights and protection of theirenvironment converged in important, if not all, respectswith the causes being fostered by these movements. Acrucial part of that understanding was the importance ofovertly representing themselves as a group of distinctiveidentity capable of acting independently in defence of theircultures, lands and environment. In contrast to the covertforms of resistance or ‘hidden transcripts’ that James Scotthas suggested are the essential ‘weapons of the weak’, inother words, the Kayapo have developed a flamboyantly‘open transcript’, consisting of their own overt representationsand public acts of opposition to Brazilian statepolicies and powers (cf. Scott 1985, 1990; Turner 1991,1992).An important aspect of this ‘open transcript’ has beenthe Kayapo’s development of new forms and techniquesof representation, including the creative use of new mediasuch as video but also adaptations of their traditional culturalforms such as ritual choreography and self-decoration,employed in staging demonstrations and politicalconfrontations. These innovative forms of representation,and the support from national and international civil societythey have helped to win, in sum, have also been important‘weapons’ in the Kayapo struggle (Fajans-Turner 2004,Turner 1991, Keck and Sikkink 1998).The Kayapo have been able to co-opt and employ thepowers derived from these extraneous sources by drawingupon the political qualities and cultural resources developedin their traditional system. These qualities wereepitomized by their creation of the inter-ethnic allianceof ‘peoples of the Xingú’ at the Piaraçu meeting of 2003(Fajans-Turner and Turner 2005) and the new level of rituallygrounded political unity for their own people at the2006 Piaraçu meeting described at the beginning of thisarticle. If the peoples and ecosystem of the Amazon are tobe saved from the ravages of the Brazilian regime’s developmentalistpolicies, they will owe much to the Kayapo’sability to exploit the conflicting currents of global civilsociety and discordant elements of modern state regimesas sources of new powers of resistance and adaptation. •TERENCE URNER10 ANTHROPOLOGY TODAY Vol 22 No 5, October 2006