The Persistence of Innovation in Government

The Persistence of Innovation in Government

The Persistence of Innovation in Government

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

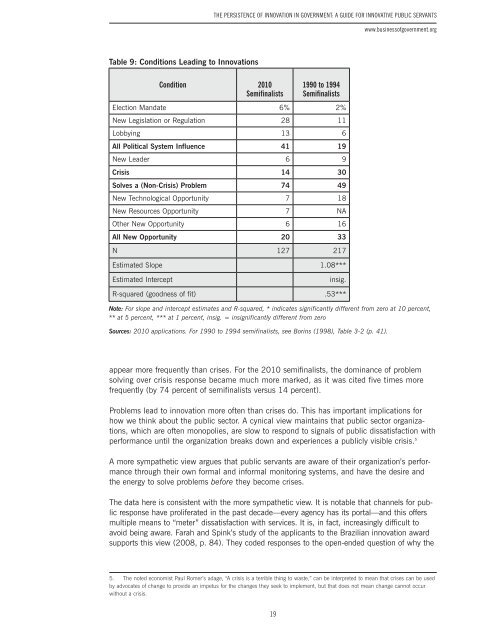

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Persistence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Innovation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Government</strong>: A Guide for Innovative Public Servantswww.bus<strong>in</strong>ess<strong>of</strong>government.orgTable 9: Conditions Lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>Innovation</strong>sCondition 2010Semif<strong>in</strong>alists1990 to 1994Semif<strong>in</strong>alistsElection Mandate 6% 2%New Legislation or Regulation 28 11Lobby<strong>in</strong>g 13 6All Political System Influence 41 19New Leader 6 9Crisis 14 30Solves a (Non-Crisis) Problem 74 49New Technological Opportunity 7 18New Resources Opportunity 7 NAOther New Opportunity 6 16All New Opportunity 20 33N 127 217Estimated Slope 1.08***Estimated Intercept<strong>in</strong>sig.R-squared (goodness <strong>of</strong> fit) .53***Note: For slope and <strong>in</strong>tercept estimates and R-squared, * <strong>in</strong>dicates significantly different from zero at 10 percent,** at 5 percent, *** at 1 percent, <strong>in</strong>sig. = <strong>in</strong>significantly different from zeroSources: 2010 applications. For 1990 to 1994 semif<strong>in</strong>alists, see Bor<strong>in</strong>s (1998), Table 3-2 (p. 41).appear more frequently than crises. For the 2010 semif<strong>in</strong>alists, the dom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>of</strong> problemsolv<strong>in</strong>g over crisis response became much more marked, as it was cited five times morefrequently (by 74 percent <strong>of</strong> semif<strong>in</strong>alists versus 14 percent).Problems lead to <strong>in</strong>novation more <strong>of</strong>ten than crises do. This has important implications forhow we th<strong>in</strong>k about the public sector. A cynical view ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s that public sector organizations,which are <strong>of</strong>ten monopolies, are slow to respond to signals <strong>of</strong> public dissatisfaction withperformance until the organization breaks down and experiences a publicly visible crisis. 5A more sympathetic view argues that public servants are aware <strong>of</strong> their organization’s performancethrough their own formal and <strong>in</strong>formal monitor<strong>in</strong>g systems, and have the desire andthe energy to solve problems before they become crises.<strong>The</strong> data here is consistent with the more sympathetic view. It is notable that channels for publicresponse have proliferated <strong>in</strong> the past decade—every agency has its portal—and this <strong>of</strong>fersmultiple means to “meter” dissatisfaction with services. It is, <strong>in</strong> fact, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly difficult toavoid be<strong>in</strong>g aware. Farah and Sp<strong>in</strong>k’s study <strong>of</strong> the applicants to the Brazilian <strong>in</strong>novation awardsupports this view (2008, p. 84). <strong>The</strong>y coded responses to the open-ended question <strong>of</strong> why the5. <strong>The</strong> noted economist Paul Romer’s adage, “A crisis is a terrible th<strong>in</strong>g to waste,” can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted to mean that crises can be usedby advocates <strong>of</strong> change to provide an impetus for the changes they seek to implement, but that does not mean change cannot occurwithout a crisis.19