Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics EJAIB

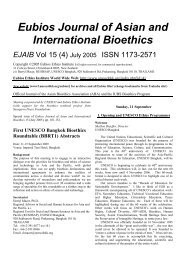

Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics EJAIB

Eubios Journal of Asian and International Bioethics EJAIB

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

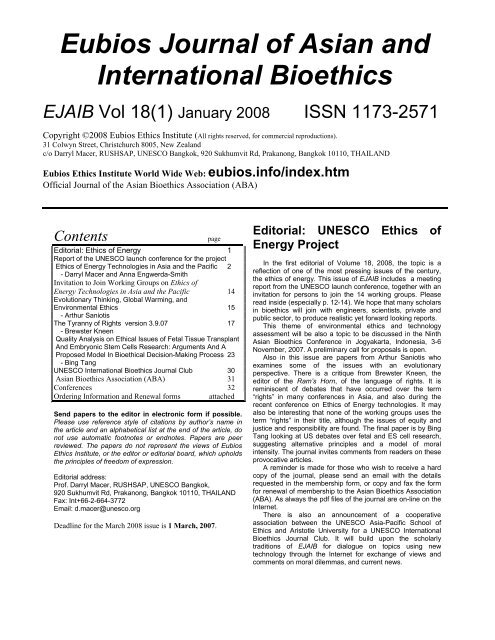

<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong><strong>EJAIB</strong> Vol 18(1) January 2008 ISSN 1173-2571Copyright ©2008 <strong>Eubios</strong> Ethics Institute (All rights reserved, for commercial reproductions).31 Colwyn Street, Christchurch 8005, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>c/o Darryl Macer, RUSHSAP, UNESCO Bangkok, 920 Sukhumvit Rd, Prakanong, Bangkok 10110, THAILAND<strong>Eubios</strong> Ethics Institute World Wide Web: eubios.info/index.htmOfficial <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> Association (ABA)ContentspageEditorial: Ethics <strong>of</strong> Energy 1Report <strong>of</strong> the UNESCO launch conference for the projectEthics <strong>of</strong> Energy Technologies in Asia <strong>and</strong> the Pacific 2- Darryl Macer <strong>and</strong> Anna Engwerda-SmithInvitation to Join Working Groups on Ethics <strong>of</strong>Energy Technologies in Asia <strong>and</strong> the Pacific 14Evolutionary Thinking, Global Warming, <strong>and</strong>Environmental Ethics 15- Arthur SaniotisThe Tyranny <strong>of</strong> Rights version 3.9.07 17- Brewster KneenQuality Analysis on Ethical Issues <strong>of</strong> Fetal Tissue TransplantAnd Embryonic Stem Cells Research: Arguments And AProposed Model In Bioethical Decision-Making Process 23- Bing TangUNESCO <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Club 30<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> Association (ABA) 31Conferences 32Ordering Information <strong>and</strong> Renewal forms attachedSend papers to the editor in electronic form if possible.Please use reference style <strong>of</strong> citations by author’s name inthe article <strong>and</strong> an alphabetical list at the end <strong>of</strong> the article, donot use automatic footnotes or endnotes. Papers are peerreviewed. The papers do not represent the views <strong>of</strong> <strong>Eubios</strong>Ethics Institute, or the editor or editorial board, which upholdsthe principles <strong>of</strong> freedom <strong>of</strong> expression.Editorial address:Pr<strong>of</strong>. Darryl Macer, RUSHSAP, UNESCO Bangkok,920 Sukhumvit Rd, Prakanong, Bangkok 10110, THAILANDFax: Int+66-2-664-3772Email: d.macer@unesco.orgDeadline for the March 2008 issue is 1 March, 2007.Editorial: UNESCO Ethics <strong>of</strong>Energy ProjectIn the first editorial <strong>of</strong> Volume 18, 2008, the topic is areflection <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the most pressing issues <strong>of</strong> the century,the ethics <strong>of</strong> energy. This issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>EJAIB</strong> includes a meetingreport from the UNESCO launch conference, together with aninvitation for persons to join the 14 working groups. Pleaseread inside (especially p. 12-14). We hope that many scholarsin bioethics will join with engineers, scientists, private <strong>and</strong>public sector, to produce realistic yet forward looking reports.This theme <strong>of</strong> environmental ethics <strong>and</strong> technologyassessment will be also a topic to be discussed in the Ninth<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> Conference in Jogyakarta, Indonesia, 3-6November, 2007. A preliminary call for proposals is open.Also in this issue are papers from Arthur Saniotis whoexamines some <strong>of</strong> the issues with an evolutionaryperspective. There is a critique from Brewster Kneen, theeditor <strong>of</strong> the Ram’s Horn, <strong>of</strong> the language <strong>of</strong> rights. It isreminiscent <strong>of</strong> debates that have occurred over the term“rights” in many conferences in Asia, <strong>and</strong> also during therecent conference on Ethics <strong>of</strong> Energy technologies. It mayalso be interesting that none <strong>of</strong> the working groups uses theterm “rights” in their title, although the issues <strong>of</strong> equity <strong>and</strong>justice <strong>and</strong> responsibility are found. The final paper is by BingTang looking at US debates over fetal <strong>and</strong> ES cell research,suggesting alternative principles <strong>and</strong> a model <strong>of</strong> moralintensity. The journal invites comments from readers on theseprovocative articles.A reminder is made for those who wish to receive a hardcopy <strong>of</strong> the journal, please send an email with the detailsrequested in the membership form, or copy <strong>and</strong> fax the formfor renewal <strong>of</strong> membership to the <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> Association(ABA). As always the pdf files <strong>of</strong> the journal are on-line on theInternet.There is also an announcement <strong>of</strong> a cooperativeassociation between the UNESCO Asia-Pacific School <strong>of</strong>Ethics <strong>and</strong> Aristotle University for a UNESCO <strong>International</strong><strong>Bioethics</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Club. It will build upon the scholarlytraditions <strong>of</strong> <strong>EJAIB</strong> for dialogue on topics using newtechnology through the Internet for exchange <strong>of</strong> views <strong>and</strong>comments on moral dilemmas, <strong>and</strong> current news.

2<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> 18 (January 2008)Report <strong>of</strong> the UNESCOlaunch conference for theproject Ethics <strong>of</strong> EnergyTechnologies in Asia <strong>and</strong>the PacificHosted by UNESCO Bangkok in collaboration with theMinistry <strong>of</strong> Science <strong>and</strong> Technology <strong>and</strong> the Ministry <strong>of</strong>Energy, Thail<strong>and</strong>Imperial Tara Hotel, Bangkok, 26-28 September 2007Prepared by Darryl Macer <strong>and</strong> Anna Engwerda-SmithRUSHSAP, UNESCO Bangkok,920 Sukhumvit Rd, Prakanong, Bangkok 10110, THAILANDEmail: d.macer@unesco.orgBackgroundThis regional conference launched the project ‘Ethics <strong>of</strong>Energy Technologies in Asia <strong>and</strong> the Pacific’. The meetingwas hosted by the Regional Unit in Social <strong>and</strong> HumanSciences in Asia <strong>and</strong> the Pacific (RUSHSAP) at UNESCOBangkok with the cooperation <strong>of</strong> the Thai Ministry <strong>of</strong> Science<strong>and</strong> Technology <strong>and</strong> the Thai Ministry <strong>of</strong> Energy. Twospecialized institutes <strong>of</strong> the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Science <strong>and</strong>Technology, the National Metal <strong>and</strong> Materials TechnologyCenter (MTEC) <strong>and</strong> the National Science <strong>and</strong> TechnologyDevelopment Agency (NSTDA) also cooperated.This project is linked to several key activities <strong>of</strong> UNESCOBangkok, which include ethics <strong>of</strong> science <strong>and</strong> technology,environmental ethics, philosophical dialogues, linkingresearch with policy-making <strong>and</strong> promoting the culture <strong>of</strong>peace. UNESCO is committed to working with regionalMinistries <strong>of</strong> Science <strong>and</strong> Technology in implementing theMinisterial ‘Bangkok Declaration on Ethics in Science <strong>and</strong>Technology’ issued at the conclusion <strong>of</strong> the 4 th Session <strong>of</strong> theCOMEST on 25 March 2005.There has been prior discussion <strong>of</strong> some aspects <strong>of</strong> theethics <strong>of</strong> energy in a previous UNESCO report from the WorldCommission on the Ethics <strong>of</strong> Scientific Knowledge <strong>and</strong>Technology (COMEST) Sub-Committee on ‘The Ethics <strong>of</strong>Energy’, 2000. There are also various activities related toenergy being conducted in different United Nations agencies.UNESCO is the only UN agency, however, that has ethics asone <strong>of</strong> its overarching priority areas.This project will develop these multidisciplinary <strong>and</strong>cross-cultural discussions in a context that is relevant to theAsia <strong>and</strong> Pacific region. As the global region with the fastestannual growth in energy dem<strong>and</strong>, countries face increasingpressure to articulate their energy policies. There are manycountries in the region that are considering adopting nuclearenergy, including Australia, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iran,Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Thail<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Vietnam. And there areother countries in the region already using nuclear energy,including China, DPR Korea, India, Japan, Pakistan <strong>and</strong>Republic <strong>of</strong> Korea. As the international focus on climatechange intensifies, the environmental <strong>and</strong> social ethics <strong>of</strong> allenergy choices need be considered holistically. This meeting<strong>and</strong> project is not intended to duplicate the numerousmeetings being held on energy <strong>and</strong> environment, but to openup ethical <strong>and</strong> value questions that have <strong>of</strong>ten beenneglected, <strong>and</strong> to depoliticize discussions on environmentalethics to produce substantive cross-cultural outputs that willbe relevant for long-term policy making within each nation.SummaryThere were approximately one hundred conferenceparticipants <strong>of</strong> evenly balanced gender from Australia,Bangladesh, France, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Jordan,Korea, Nepal, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>, Sri Lanka, Thail<strong>and</strong>, the UnitedKingdom, <strong>and</strong> Vietnam. Participants attended in theirindividual capacity <strong>and</strong> came from diverse backgrounds,including engineering, government, institutional advisorybodies, civil society organizations (CSOs), energy-relatedindustries, education, marketing, <strong>and</strong> academia. Thedisciplines amongst academics ranged from engineering,philosophy, ethics, environmental science, medicine, ecology<strong>and</strong> social work. Two members <strong>of</strong> the World Commission onthe Ethics <strong>of</strong> Scientific Knowledge <strong>and</strong> Technology(COMEST) were present: Dr Somsak Chunharas <strong>and</strong> MsNadja Tollemache.After welcome addresses from the Director <strong>of</strong> UNESCOBangkok, the Minister for Science <strong>and</strong> Technology (Thail<strong>and</strong>),<strong>and</strong> Deputy Permanent Secretary for the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Energy(Thail<strong>and</strong>), Dr Darryl Macer <strong>of</strong> UNESCO Bangkok outlined therationale for the project. There were sessions on:• Ethical worldviews <strong>and</strong> the environment;• Visions <strong>of</strong> the future: Ethical views <strong>of</strong> differentenergy strategies;• North-South divide <strong>and</strong> energy equity;• Constructing & reconciling visions <strong>of</strong> differentcommunities;• Ethics <strong>of</strong> nuclear power <strong>and</strong> alternative energysystems; <strong>and</strong>• Energy independence <strong>and</strong> security.Presenters were asked to give 15 minute talks, followedby questions. The plenary sessions were interspersed withbreakout working group sessions throughout the conference.As the focus was on dialogue, <strong>and</strong> as delegates wereconsidered to attend in their individual capacity rather thenrepresenting their country, there was no statement issued atthe meeting. The working group sessions were intended toset the themes for ongoing working groups that will producereports over the course <strong>of</strong> the project. The abstracts,discourse <strong>and</strong> proceedings <strong>of</strong> the meeting will be availableonline at http://www.unescobkk.org/index.php?id=energyethics.Meeting reportThe Opening session for the conference commencedwith a welcoming address from Dr Sheldon Shaeffer, theRegional Director <strong>of</strong> UNESCO Bangkok. Dr Schaefferacknowledged the cooperation <strong>of</strong> Thai government partners inhosting the meeting. He noted that energy was a topic <strong>of</strong>immediate global concern. He stressed that it was not the role<strong>of</strong> UNESCO to be prescriptive about countries’ energychoices, but rather to be a neutral broker <strong>of</strong> interdisciplinary<strong>and</strong> interregional dialogues. The project aimed to develop adeeper public underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> the complexities <strong>of</strong> differentenergy sources <strong>and</strong> technologies for meeting the region’sprojected energy needs, including the strengths <strong>and</strong>weaknesses <strong>of</strong> energy industries (considering environmental,economic, social <strong>and</strong> legal aspects).There was an address from Pr<strong>of</strong> Yongyuth Yuthavong,Minister <strong>of</strong> Science <strong>and</strong> Technology, Thail<strong>and</strong>, who outlinedthe basic problems with energy as those <strong>of</strong> ever-increasingdem<strong>and</strong>, rising prices, depletion <strong>of</strong> fossil fuels <strong>and</strong> the impacton climate change. Pr<strong>of</strong> Yongyuth appealed for a balancedapproach to assessing alternative energy choices, whichrecognized that all attempts to solve problems have problems,<strong>and</strong> that lobbying on single agendas was not productive.Governments, civil society groups <strong>and</strong> educators all had rolesin increasing public awareness <strong>and</strong> encouragingenvironmental <strong>and</strong> social responsibility. He suggested thatindividuals, industries <strong>and</strong> countries could consider voluntarycodes <strong>of</strong> ethics to guide their activities.There followed an address from Dr Kurujit Nakornthap,Deputy Permanent Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Energy,

<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> 18 (January 2008) 5BT cotton in India, where despite having a reasonable policy,thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> farmers had committed suicide. Dr Gupta askedwhat role ethicists could play in narrowing this gap, to whichPr<strong>of</strong> Nesy said that ethical principles <strong>of</strong> informed consent <strong>and</strong>public participation needed to be more widely acknowledged,<strong>and</strong> that education was vital in giving citizens information <strong>and</strong>involving them in the discussion about energy.Dr Samai Jai-in from the National Metal <strong>and</strong> MaterialsTechnology Center (MTEC), Thail<strong>and</strong>, talked about thecurrent energy revolution in bioenergy, which was in its earlystages <strong>of</strong> implementation. He drew on examples fromThail<strong>and</strong>’s experience in the past decade to explore theopportunity for science <strong>and</strong> technology to become enablingfactors in the improvement <strong>of</strong> the environment, energyefficiency <strong>and</strong> equity <strong>of</strong> the rural economy. He noted thatagriculture comprised 9 per cent <strong>of</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong>’s GDP <strong>and</strong> 39per cent <strong>of</strong> employment, <strong>and</strong> was still the main sustainingforce <strong>of</strong> regional areas. Thail<strong>and</strong> was in transition from ahydrocarbon economy in 2000 to a carbohydrate economy in2030, although much research <strong>and</strong> development was stillneeded. Dr Jai-in noted the foresight <strong>of</strong> His Majesty the King<strong>of</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong>, who had established an ethanol distillation plant22 years ago. Thail<strong>and</strong> had an ethanol yield productivity far inexcess <strong>of</strong> the world average, <strong>and</strong> palm oil was also exp<strong>and</strong>ingas an energy crop, particularly in the south <strong>of</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong> wherethe best growing conditions were found. Palm oil cultivationwas suitable for degraded agricultural soils previously used togrow oranges. Along with food, feed <strong>and</strong> fiber crops, bi<strong>of</strong>uelsincluding palm oil, cassava, <strong>and</strong> sunflowers <strong>of</strong>feredopportunities for self-sufficiency <strong>and</strong> development in ruralcommunities.In discussion, Dr Charn Mayot commented that whilstbioenergy was strongly supported by many scientists <strong>and</strong>engineers working in the field, ordinary people did not havean awareness <strong>of</strong> or an appreciation for it. Dr Jai-inacknowledged this problem, saying that although manydedicated scientists were working hard, they were notnecessarily communicating a message to the general public<strong>and</strong> had not managed to attract government funding for publicawareness <strong>and</strong> development to the same level as theemerging nuclear program. Many scientists in Thail<strong>and</strong>preferred to work quietly <strong>and</strong> independently rather thanactively promoting their work through the education system ormedia. Additionally there was also some resistance from thecar manufacturing <strong>and</strong> oil industries.Pr<strong>of</strong> On-Kwok Lai <strong>and</strong> Ms Shizuka Abe from Japanspoke on ‘Synergizing alternative-clean energy <strong>and</strong> selfsufficiencyfor the future? Interfacing the ethics <strong>of</strong> bioregionalism<strong>and</strong> energy independence’. Between 1995 <strong>and</strong>2005, East Asia <strong>and</strong> South Asia reported the strongestregional economic growth in the world, <strong>and</strong> South East Asia<strong>and</strong> the Pacific were growing at a rate above the worldaverage. But Asia <strong>and</strong> the Pacific were under-utilizing theirnatural sources <strong>of</strong> renewable energy, which included solarenergy, extensive river networks for hydropower, geothermalenergy <strong>and</strong> biomass. Barriers to renewable energy systemswere institutional, political, technical <strong>and</strong> financial. Renewableenergy resources also were bioregional in the territory theycovered, so there was a potential conflict betweenbioregional, potentially unstable energy systems <strong>and</strong>countries’ desires for energy independence <strong>and</strong> self-reliance.Guiding ethics insights that could be applied in the choicesregarding clean energies were available in Asia Pacificcultures, through historic folklores <strong>and</strong> myths. These could beinvoked to revitalize <strong>and</strong> rejuvenate current local ethics <strong>and</strong>they could also be adapted within a ‘global eco-ethics’.Dr Ayoub Aby-Dayyeh asked why Thail<strong>and</strong> did not usemore renewable energy, particularly natural gas over coal,which would dramatically reduce pollution. Pr<strong>of</strong> Lai declinedto answer specifically. He said, however, that a country’senergy mix really depended on the existing governance <strong>and</strong>the international sourcing or supply chain <strong>of</strong> energy. Thesupply chain for renewable energy was dominated by thedeveloped countries who owned the technology; for example,the intellectual property <strong>of</strong> solar cell technology wasdominated by Japan, Germany <strong>and</strong> the US. Dr Samai Jai-in,<strong>of</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong>’s National Metal <strong>and</strong> Materials Technology Centre(MTEC), said that in Thail<strong>and</strong> currently 76 per cent <strong>of</strong>electricity comes from natural gas. Of this 75 per cent isproduced in the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> 25 per cent is importedfrom Myanmar. There was still significant governmentinvestment in coal-fired power although there was growinginterest in the potential for small-scale renewables, such aslocal biomass production. A speaker from the Ministry <strong>of</strong>Energy also added that Thail<strong>and</strong> was a strong supporter <strong>of</strong>renewable energy development, <strong>and</strong> had, like Germany <strong>and</strong>Denmark, introduced a special tariff to make renewableenergy feasible to produce.In his presentation, ‘The risk <strong>of</strong> big energy technologies<strong>and</strong> ethical aspects <strong>of</strong> renewable energy technologies’, Pr<strong>of</strong>Pil-Ryul Lee from the Republic <strong>of</strong> Korea argued thatrenewable energy sources <strong>of</strong>fered a far more realistic solutionthan those <strong>of</strong> fossil fuels or nuclear power for fighting globalwarming <strong>and</strong> climate change. From the ethical point <strong>of</strong> view,nuclear power presented many problems at each point <strong>of</strong> thecomplex supply chain, including uranium mining, enrichment,<strong>and</strong> risk management in a functioning plant. It was a highlycentralized <strong>and</strong> state-controlled source <strong>of</strong> energy that did notpromote participatory democracy. Nuclear <strong>and</strong> fossil-fuelbased power also triggered international conflicts. On theother h<strong>and</strong>, renewable energies such as solar, wind, smallhydro, biomass, geothermal <strong>and</strong> tidal energy are <strong>of</strong>tendecentralized <strong>and</strong> can be used in remote areas without a solidenergy supply system. While they can cause conflicts oversocial <strong>and</strong> aesthetic impacts this conflict remains at a local ornational level.Pr<strong>of</strong> Lee’s presentation was followed by a discussionabout the feasibility <strong>of</strong> small-scale renewable technology in aworld with insatiable energy dem<strong>and</strong>s. Dr Alastair Gunnacknowledged that local small-scale renewable energysolutions were attractive, but asked whether we couldrealistically power aluminum smelters or paper mills, forinstance, with renewable energy. Dr Lee replied that he didnot necessarily advocate for small-scale green energytechnologies in all circumstances, <strong>and</strong> that the best energymix depended local conditions, including living conditions <strong>and</strong>rates <strong>of</strong> energy consumption. Dr Abhik Gupta commented thatenergy could become a great limiting factor on sustainingcivilization beyond a certain point. At present we are reachingthe environmental <strong>and</strong> ethical limits <strong>of</strong> carbon fuels <strong>and</strong>nuclear power, but solar <strong>and</strong> wind power might not be enoughto sustain to sustain industrial production which traditionallyrelies on coal. He said that there was a real need for abreakthrough in solar <strong>and</strong> wind research in terms <strong>of</strong>conversion efficiency, stored energy efficiency <strong>and</strong> so on. Thebest option for now could be to cultivate multiple energysources appropriate to a country’s energy needs.Pr<strong>of</strong> N. Manohar from India spoke on ‘Energytechnologies for the future’, noting that the TRIPs (Agreementon Trade-Related Aspects <strong>of</strong> Intellectual Property Rights)process worked towards the internationalization <strong>of</strong> the energyindustry through market dynamism <strong>and</strong> free trade. Energytechnology preferences for the region should be attuned to itscultural values, however. Given the environmental <strong>and</strong>security hazards implicit in many energy options, the regionneeded to avoid tension <strong>and</strong> instability <strong>and</strong> focus on peace<strong>and</strong> development. There was a role for the internationalcommunity to facilitate the transfer <strong>of</strong> clean energy technologyto South <strong>Asian</strong> countries who could not previously afford it.Further, stricter international ethical st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong>compliance cultures were needed to ensure safety <strong>and</strong> theuse <strong>of</strong> energy technologies for peaceful purposes. Some

6<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> 18 (January 2008)discussion ensued, following on from the previous discussion,about the scale <strong>of</strong> energy technologies <strong>and</strong> the implicationsfor governance, centralization <strong>of</strong> decision-making <strong>and</strong>democratic participation. Pr<strong>of</strong> Manohar said that hisrecommendations would be to decentralize power generationfacilities, utilize local resources wherever possible, <strong>and</strong>develop international cooperation on the peaceful use <strong>of</strong>energy technologies.The second day, 27 September, started with a sessionon the North-South Divide <strong>and</strong> energy equity. Dr MasamiNakata from UNESCO’s Jakarta <strong>of</strong>fice reported onUNESCO’s Natural Science Sector’s efforts for improvingenergy equity. Dr Nakata said that there was already a largepopulation in lesser developed countries who did not havegood access to conventional technology such as electricity<strong>and</strong> fossil fuels. A decrease in availability <strong>of</strong> fossil fuels in thefuture could heighten inequity in energy access. UNESCO’sNatural Science Sector was therefore working on renewableenergy as a way to improve energy equity <strong>and</strong> promoteenvironmentally responsible development. She outlinedseveral projects the <strong>of</strong>fice was working on, including theRenewable Energy Database, led by Pr<strong>of</strong> Kumar <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Asian</strong>Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology in collaboration with UNESCAP <strong>and</strong>UNESCO; the Gender Mainstreaming in Energy project, ledby the University <strong>of</strong> Indonesia in collaboration with UNESCO;<strong>and</strong> e-learning distance education courses in the Asia-Pacificon renewable energy.Dr Pil-Ryul Lee asked Dr Nakata about the extent <strong>of</strong>cooperation between her <strong>of</strong>fice in Jakarta <strong>and</strong> the Parisheadquarters <strong>of</strong> UNESCO. He was aware that there was asummer school on renewable energy at headquarters as wellas many programs on technology transfer to <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong>African countries. There was a lot <strong>of</strong> communication withUNESCO headquarters, she replied, as they were in thesame organization <strong>and</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> people workingspecifically on energy issues was few. Headquarters’geographical focus was, however, on Africa, whereas theJakarta <strong>of</strong>fice was <strong>of</strong> course focused on Asia. Dr Maceradded that in many <strong>of</strong> the UN organizations, the focus was onthe continent with the direst situation, which is Africa.However, this has meant that the Asia Pacific region receivesless attention, both in terms <strong>of</strong> funding <strong>and</strong> activities fromheadquarters. This was one <strong>of</strong> the issues <strong>of</strong> working in aregion which has intermediate <strong>and</strong> very diverse status. Thefield <strong>of</strong>fices in Asia <strong>and</strong> the Pacific therefore networked withmany partners, as in the project described by Dr Nakata <strong>and</strong>as in the Ethics <strong>of</strong> Energy project being launched at theconference.Dr Charn Mayot asked for more information on the targetaudience <strong>of</strong> the e-learning programs on renewable energymentioned by Dr Nakata. Were they intended for technicalpeople, such as engineers, or for ordinary people who wantedbioenergy in rural communities, for example? Dr Nakata saidthat originally the target had been graduate students, middlelevelpolicymakers, the NGOs <strong>and</strong> also the private sector, butthat in practice many students joined <strong>and</strong> more research <strong>and</strong>refinement was needed to recruit policymakers for the nextround <strong>of</strong> courses.Dr Alastair S. Gunn from New Zeal<strong>and</strong> spoke on ‘Energy,efficiency <strong>and</strong> equity’, noting the inequities in access toenergy both between <strong>and</strong> within nations, in part because <strong>of</strong>natural endowments <strong>and</strong> financial resources that determinedthe number <strong>of</strong> ‘energy slaves’ available to each person. DrGunn suggested avoiding generalizations between ‘rich’ <strong>and</strong>‘poor’ countries, noting that states <strong>of</strong> development were notstatic, <strong>and</strong> in the Asia Pacific region especially enormousgains had been made. Nevertheless, there were importantquestions <strong>of</strong> socio-economic equity in determining who willbear the costs <strong>of</strong> a reduction in carbon emissions <strong>and</strong>pollution. While most people in developing countries (<strong>and</strong> thepoor within affluent countries) were seeking ‘social <strong>and</strong>economic justice ... freedom <strong>and</strong> self-determination’, the postaffluentwere rejecting values <strong>of</strong> over-consumption,technological efficiency <strong>and</strong> economic growth. Dr Gunnargued that the affluent have no right to preach subsistenceliving to the poor, however. There was no realistic way toreduce energy dem<strong>and</strong> in developing countries, although itmight be <strong>of</strong>fset by innovation <strong>and</strong> improvements in efficiencyin both generation <strong>and</strong> utilization.There was a diverse range <strong>of</strong> questions about Dr Gunn’spresentation, <strong>and</strong> especially about New Zeal<strong>and</strong>’s ability toinnovate in energy policy relative to other countries in the AsiaPacific region. Dr Gunn felt that New Zeal<strong>and</strong> was a historicalinnovator in social <strong>and</strong> environmental policy, but this was inpart due to the fact that it was a lucky country: it was mediumsized,relatively wealthy, had a mild climate, no majorenvironmental problems, <strong>and</strong> was a highly educated,democratically literate population that expected governmentsto be responsive to their concerns <strong>and</strong> consult on major policydecisions. The population was relatively low <strong>and</strong> stable, whichmeant that inhabitants could lead an affluent lifestyle thatmight be environmentally disastrous elsewhere.Dr Sumittra Charojrochkul <strong>and</strong> Mr Issa Abyad askedspecifically about how New Zeal<strong>and</strong> planned to accommodatedairy farming within its target to become ‘carbon-neutral’ by2020; as cows contributed to emissions by producing muchmethane. Dr Gunn said that this was a subject <strong>of</strong> discussionin New Zeal<strong>and</strong>. The problem was that cows have inefficientdigestive systems. Possible options were improving thedigestive system <strong>of</strong> cows or improving the quality <strong>of</strong> the feedprovided through genetic modification.In his presentation, ‘Global warming <strong>and</strong> disparity inenergy consumption between North <strong>and</strong> South: The need forglobal justice principles to take care <strong>of</strong> the environment’, DrSoraj Hongladarom from Thail<strong>and</strong> outlined some <strong>of</strong> thearguments about the respective ethical obligations <strong>of</strong>developed <strong>and</strong> developing countries in light <strong>of</strong> the KyotoProtocol process <strong>and</strong> climate change at large. Developedcountries had the highest per capita consumption <strong>of</strong> energy,at rates which the world would be unable to sustain if appliedto every person in China or India. Through a system <strong>of</strong>exploitation <strong>and</strong> colonialism (old or new), the North reapedthe benefits, leaving the South to scramble for what was left.Yet some rich countries such as the USA <strong>and</strong> Australia didnot sign the Kyoto Protocol, arguing that developing countriesalso needed to curb energy consumption, <strong>and</strong> to strengthentheir legal <strong>and</strong> political frameworks against environmentaldegradation <strong>and</strong> corruption. Dr Hongladarom called for asystem <strong>of</strong> global justice that would transcend nationalinterests <strong>and</strong> recognize that all countries shared the sameplanet. A fair system <strong>of</strong> sharing, where the North shared theexpertise <strong>and</strong> the South the resources, needed to becombined with a more prudent use <strong>of</strong> energy <strong>and</strong>environmental mindfulness.Dr Mayot asked for some clarification on DrHongladarom’s use <strong>of</strong> the term ‘global authority’ as a corollaryto ‘global justice’. Dr Hongladarom explained that he hadused the term global authority in a wide sense. It could meanthe United Nations, but the United Nations was not asovereign power, although if the five permanent members <strong>of</strong>the Security Council worked together unanimously they couldhave some teeth. The usual conception <strong>of</strong> justice was thatthere has to be some form <strong>of</strong> power to enforce justice. So ifwe continued to rely <strong>and</strong> believe in the principle <strong>of</strong> sovereignstates then perhaps global authority was not going to beeffective. Dialogue might be another approach.Finally, Dr Amru Hydari Nazif spoke on ‘Ethical analysishardly made: Energy paths not considered in energy planningin Indonesia’. Oil, coal <strong>and</strong> gas remained Indonesia’s mostimportant energy resources, but there were also uraniumreserves that had been the subject <strong>of</strong> speculation since the1950s. Indonesia currently had three research reactors <strong>and</strong>was considering nuclear power for centralized electricity

<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> 18 (January 2008) 7generation. Dr Nazif expressed concern about the threatposed by radiotoxicity to flora <strong>and</strong> fauna, including humans<strong>and</strong> the environment. He questioned why renewable energieshad not been more seriously considered as an ‘energy path’in Indonesia <strong>and</strong> considered the appropriate point(s) in anenergy planning cycle for rigorous ethical analysis withcommunity consultation.Dr Ayoub Aby-Dayyeh asked why the Indonesians,having started on research nuclear plants in the 1970s inparallel with the South Koreans, were not more advanced innuclear power <strong>and</strong> technology. Was it because Indonesia hadplentiful oil reserves <strong>and</strong> had not felt a critical need to developalternative energy? Dr Nazif agreed that it was, althoughIndonesia was now working with the <strong>International</strong> AtomicEnergy Agency (IAEA) to progress its nuclear program.After a tea break, there was a fifth session onConstructing <strong>and</strong> reconciling visions <strong>of</strong> differentcommunities. Dr Miyako Okada-Takagi from Jap<strong>and</strong>escribed in her presentation ‘Enhancing energy educationthrough internet game content’, how Nihon University inTokyo had designed a computer game for the Tokyo ElectricPower Company (TEPCO). The game was available on thepower company’s home page, <strong>and</strong> was intended to educatethe Japanese public, particularly young people, about howenergy is generated, including nuclear, thermal <strong>and</strong>hydroelectric power. The information provided was factualinformation about the entire electric power system, frompower stations to the power supply system. Dr Okada-Takagishowed a demonstration <strong>of</strong> the game <strong>and</strong> gave out keychains featuring game characters which were distributed bythe company.There were a number <strong>of</strong> questions <strong>and</strong> comments on theeffectiveness <strong>and</strong> content <strong>of</strong> the game. Dr On-Kwok Lai saidthat game looked like it was fun to play, but to what extent didit help people to accept nuclear energy in their daily life? DrOkada-Takagi replied that although 40 per cent <strong>of</strong> Japan’senergy is supplied by nuclear power generation, theJapanese people were still extremely sensitive about nuclearenergy <strong>and</strong> this was due in part to the fact that they did notunderst<strong>and</strong> the technical aspects <strong>of</strong> it. So the gamedemystified the power generation process <strong>and</strong> was a learningexperience at the same time as being fun. Dr Masami Nakata<strong>and</strong> Dr Robert Kanaly queried the ethics <strong>of</strong> a power company(the game’s sponsor, TEPCO) taking it upon themselves toeducate the population about a product they had acommercial interest in. If the people did not underst<strong>and</strong>nuclear power, asked Dr Kanaly, surely it was theresponsibility <strong>of</strong> the government <strong>and</strong> education system ratherthan the private sector? Dr Okada-Takagi said that althoughthere were seminars held by the government <strong>and</strong> informationwas available about nuclear power, it was not presented in anentertaining way so people did not come. Also, she clarifiedthat in addition to the game about nuclear energy, there weregames about other systems such as hydro power <strong>and</strong> thermalpower. At the company’s request, the content <strong>of</strong> the gameswas limited to factual information about how power generationworked, rather arguing the pros <strong>and</strong> cons <strong>of</strong> different energytypes.Pr<strong>of</strong> John Weckert from Australia analyzed twoarguments used in the energy debate: ‘If we don’t others will’,<strong>and</strong> ‘we won’t until others do’. Pr<strong>of</strong> Weckert considered thevalidity <strong>of</strong> these arguments, <strong>of</strong>ten used in Australia withregards to action on climate change, in terms <strong>of</strong>consequentialist <strong>and</strong> deontological points <strong>of</strong> view. Indetermining its energy policy, should a country judge a policyby its likely consequences (including the harm caused, effectson other countries by way <strong>of</strong> setting an example, <strong>and</strong> thelikely effectiveness in combating climate change)? Where theconsequences <strong>of</strong> a national policy appear to have little impacton the global community as a whole, should a country dowhat is ethically right anyway, even at cost to its economy<strong>and</strong> citizens’ livelihoods?Pr<strong>of</strong> Weckert received a question about his personalopinion regarding uranium issues in Australia, <strong>and</strong> also thereason why Australia did not sign the Kyoto Protocol.Regarding the Kyoto Protocol, he said that the two mainarguments were that the US <strong>and</strong> China had not signed it, <strong>and</strong>Australia’s foreign policy was heavily influenced by the US;<strong>and</strong> that Australia’s economy was very reliant on brown coal<strong>and</strong> to curb emissions dramatically would have an impact oneconomic growth <strong>and</strong> employment. Regarding nuclear power,he said that he was not a scientist, but personally he felt thatpolitical sensitivity about nuclear power indicated that it wasnot as safe as it was made out to be. Dr Jasdev Rai made theobservation that the argument – ‘if we don’t sell it, somebodyelse will’ – was also used in the arms industry. He made thepoint that this argument did not consider that if we sell, othersmight sell it at a more competitive price with fewersafeguards. Pr<strong>of</strong> Weckert agreed that if Australia solduranium with fairly stringent safeguards, that would make itsuranium less attractive in some ways than uranium fromcountries that didn’t have those safeguards, <strong>and</strong> it might wellmake it more expensive at various levels <strong>of</strong> its transportation<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> so on. Australia might then come under pressureto lower its safeguards to avoid being undercut.Dr Nguyen Hoang Tri from Vietnam spoke about energydem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> consumption in Vietnam. Like many othercountries, the dem<strong>and</strong> for energy in Vietnam was increasingas a result <strong>of</strong> increased use <strong>of</strong> air-conditioning, increasedprivate vehicle ownership, increased consumption <strong>of</strong> meat<strong>and</strong> dairy, <strong>and</strong> cycles <strong>of</strong> domestic consumption <strong>and</strong> overwork.Dr Ayoub Aby-Dayyeh asked about technology transferinto Vietnam. If Vietnam was to develop renewable energies,how would it develop the technology for its people to use, <strong>and</strong>could it compete in technological development <strong>and</strong> researchwith the ever developing world market sponsored by wealthycountries <strong>and</strong> companies? Dr Hoang Tri said that whilepreviously, Vietnam had to choose between Westerncountries <strong>and</strong> the former Soviet states for technicalcooperation, international relationships were now becomingmore open, <strong>and</strong> Vietnam had many contacts in Japan <strong>and</strong>Germany <strong>and</strong> so on. Dr Masami Nakata noted that Vietnamhad in fact very promising indigenous biogas technology also.Dr Abhik Gupta asked about how the VietnameseGovernment was planning for the tremendous increases inenergy dem<strong>and</strong> driven by the current rapid pace <strong>of</strong>infrastructure development in Vietnam. Dr Hoang Tri repliedthat Vietnam was looking at a number <strong>of</strong> options. Biogas wasan attractive possibility, highlighted as a priority in the 21 stGovernment Agenda. Some experiments from Thail<strong>and</strong> inethanol <strong>and</strong> biodiesel could also prove very useful forVietnam because Vietnam was an agricultural country.Hydroelectricity <strong>and</strong> nuclear energy were also beingconsidered.Dr Ngo Thi Tuyen from Vietnam spoke on aspects <strong>of</strong> herwork as Deputy Director at the Center <strong>of</strong> EducationTechnology, for the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education <strong>and</strong> Training. TheCenter promoted environmental education in a ‘ConfucianHeritage cultural context’ that stressed interpersonalrelationships <strong>and</strong> group cohesion in debates. Environmentaleducation in schools – through the arts <strong>and</strong> sciencescurriculum, outdoor activities <strong>and</strong> care <strong>of</strong> the classroomenvironment – is an important way to make communityattitudes more considerate <strong>of</strong> the environment. Ms Tuyen toldthe conference about children’s fairs that had been organizedin schools for exchanging <strong>and</strong> sharing used things, clothes,toys <strong>and</strong> books. In order to encourage a culture <strong>of</strong> saving <strong>and</strong>sharing, children brought in things they didn’t need from home<strong>and</strong> exchanged them for others, or made things such as dolls’clothes from recycled fabric.

8<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> 18 (January 2008)Dr Masami Nakata asked whether the energy educationcampaign differentiated between children in big cities <strong>and</strong>rural areas in Vietnam. Her underst<strong>and</strong>ing was that even theelectrification rate in Vietnam was not that high, <strong>and</strong> thatmany people <strong>and</strong> children did not even have access to awater tap. What kind <strong>of</strong> education was necessary for childrenin rural areas who had no access to energy or water? Ms ThiTuyen replied that the campaign was for children in all 64provinces <strong>of</strong> Vietnam, <strong>and</strong> that the principles <strong>of</strong> conservingresources, sharing things <strong>and</strong> saving money were relevanteverywhere, regardless <strong>of</strong> how communities accessed wateror electricity. Dr Chemba Raghavan asked about the potentialfor extending the education campaign to the children’sfamilies, particularly mothers, who typically allocateenvironmental <strong>and</strong> financial resources in the family home. MsThi Tuyen explained that educating families could be difficult,but that the education campaign had involved parents byinviting them to meetings about the fair project, asking themto organize things to bring from home <strong>and</strong> raising awarenessabout what the children were learning at school.The afternoon session was on Ethics <strong>of</strong> Nuclear Power<strong>and</strong> Alternative Energy Systems. Ms Puttida Suriwong <strong>and</strong>Mr Pahuton Sriwichai, representatives <strong>of</strong> Thai Youth Leadersfor Ethics in Science <strong>and</strong> Technology, told the conferenceabout a project they had planned at the joint UNESCO-National Science Museum (NSM) Youth Leaders in Ethics <strong>of</strong>Science <strong>and</strong> Technology Workshop in 2007. The projectwould be done in college dorms, involving a competitionabout which dorm groups could collectively reduce theirelectricity consumption by the greatest amount.Mr Issa Abyad commented that he thought the focus <strong>of</strong>the competition should be on fun, <strong>and</strong> that the competitioncould be based on a reduction in electricity bills, <strong>and</strong> thestudents said they had in fact incorporated this into the design<strong>of</strong> the competition. Dr Chemba Raghavan congratulated thestudents on their initiative <strong>and</strong> asked for further details on therole play component; she also suggested that the studentsthink about the evaluation component <strong>of</strong> the project to assesswhether it had actually changed behaviour.Dr Darryl Macer explained that the students had spenttwo days at the workshop in various introductory lectures <strong>and</strong>group activities <strong>and</strong> games. Over the coming year, UNESCO<strong>and</strong> partners such as the NSM would probably be holdingyouth leader training workshops with different sets <strong>of</strong> youngpeople seeding universities. In 2008 there would also besome international youth exchange forums on the ethics <strong>of</strong>energy. If participants or other parties were with a foreignuniversity <strong>and</strong> wanted to bring some <strong>of</strong> their students in thesummer holidays to Thail<strong>and</strong> or another country in the regionUNESCO would try to develop this.Dr Sumittra Charojrochkul from MTEC, Thail<strong>and</strong>, spokeabout solid oxide fuel cells <strong>and</strong> the potential they representedas a source <strong>of</strong> renewable energy that did not depend onclimate or weather. Solid oxide fuel cells were electrochemicalenergy conversion devices which generated energy fromhydrogen (from hydrocarbon) <strong>and</strong> oxygen (from air). A currentresearch project at Thail<strong>and</strong>’s National Metal <strong>and</strong> MaterialsTechnology Center (MTEC) was investigating bioethanolmodification for use as a fuel in solid oxide fuel cells, <strong>and</strong> theycould provide village-based power.Ms Tanuja Bhattacharajee commented that solid oxidefuel cells were a promising technology. She asked aboutwhether there were any life cycle analyses on the hydrogenused in the fuel cells. Dr Charojrochkul said that she wasaware <strong>of</strong> some lifecycle analyses but had not done anyherself. Pure hydrogen produced from fossil fuels was notcarbon-neutral, but the hydrogen could also be produced fromother sources, like ethanol, which did not generate extracarbon into the cycle. Phosphoric acid was one type <strong>of</strong> fuelused as an electrolyte, but for the solid oxide fuel cellphosphoric acid was not used at all. Dr Obelin Sidjabat askedabout electricity production capacity <strong>of</strong> solid oxide fuel cells<strong>and</strong> how big the units were if installed in a village. DrCharojrochkul replied that the 1 kilowatt Swiss-made modelwas about the size <strong>of</strong> a household fridge. The biggercombined cycle model had a fuel cell <strong>of</strong> about 150 kilowattwith a micro turbine <strong>of</strong> another 70 kilowatts. Dr MasamiNakata asked what the lifetime <strong>of</strong> a solid oxide fuel cell was,<strong>and</strong> about the cost <strong>of</strong> electricity generation. Dr Charojrochkulsaid that the capital costs were very expensive, aboutUS$1000 per kilowatt, because production was not on acommercial scale yet. The running or operation costs werecomparable to existing power generation. Regarding thelifetime <strong>of</strong> the fuel cell, she said that they were currentlytesting this with a view to reaching the st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>of</strong> othercomparable commercial products. The type <strong>of</strong> fuel cell shehad been talking about was ceramic, so it did not release anytoxic substances in l<strong>and</strong>fill <strong>and</strong> was simple to dispose <strong>of</strong>.Pr<strong>of</strong> S. Panneerselvam from India spoke on ‘Theenvironmental ethical implications <strong>of</strong> biotechnology as aknowledge-based industry in Tamil Nadu State, India’. Henoted a traditional Indian concept in the word ‘shakti’representing energy <strong>and</strong> referring to the ‘capacity to do work’.Tamil Nadu state had forest, agricultural <strong>and</strong> plant resourceswith tremendous biodiversity. There was potential to create acritical mass <strong>of</strong> industrial activity in biotechnology, in the fields<strong>of</strong> medical healthcare (including diagnostics, vaccines,therapeutics <strong>and</strong> veterinary drugs), agriculture/food,environmental <strong>and</strong> industrial products. As India sought toreform the environmental frameworks governing moretraditional industries, the role <strong>of</strong> bioethics, biosafety, <strong>and</strong> theethical implications <strong>of</strong> genetic engineering were important incontemporary society.Pr<strong>of</strong> Panneerselvam’s presentation was followed by adiscussion with Dr Jasdev Rai about theory <strong>and</strong> practice inthe implementation <strong>of</strong> Indian law <strong>and</strong> the role <strong>of</strong> judicialactivism in significant decisions about environmental rights.Dr Fakrul Islam asked for information on Indian governmentsupport for biotechnology, to which Pr<strong>of</strong> Panneerselvamreplied that government attitudes were changing. Wherepreviously all government assistance had been focused oninformation technology, more resources were now being putinto biotechnology, especially in Tamil Nadu state. Dr AbhikGupta also added that the Indian state <strong>and</strong> the universitygrants commission were funding new biotechnologydepartments in almost all Indian universities, even at theundergraduate level. Engineering institutes were also beingencouraged to set up new departments such as in agriculturalbiotechnology, biomedical engineering <strong>and</strong> so on. Theapplications <strong>of</strong> biotechnology in pharmaceuticals <strong>and</strong>agriculture were being considered.Dr Tavivat Puntarigvivat expressed concern that a globalbiodiesel industry would soon be captured by multinationals,citing the establishment <strong>of</strong> huge plantations by US companiesin Latin America. Potentially this would <strong>of</strong>fer no benefit to thepoor who were growing the biomass. Pr<strong>of</strong> Panneerselvamsaid that he thought biodiesel could bring more income <strong>and</strong>greater self-sufficiency to the rural poor, but that the industryneeded to be regulated to protect their security. Dr AbhikGupta said that he felt that in these areas a lot <strong>of</strong> watchdogactivity was needed, particularly from ethicists, <strong>and</strong>ecologists, <strong>and</strong> particularly for maintaining natural biodiversity<strong>of</strong> flora <strong>and</strong> fauna. Another contentious area was benefitsharing<strong>and</strong> this question <strong>of</strong> copyright, which had alreadybeen the subject <strong>of</strong> controversies in India, such as that whicherupted over basmati rice.In his presentation, Dr Robert A. Kanaly from Japanasked participants to reflect on the fact that food was energy,but that it also required energy to obtain food. The production<strong>of</strong> meat placed high dem<strong>and</strong>s on energy resources <strong>and</strong> was,at least in US-style systems <strong>of</strong> intensive factory farming,based on oil <strong>and</strong> water consumption. This was becausegrowing livestock feed such as corn required large amounts <strong>of</strong>

<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> 18 (January 2008) 9chemical fertilizer <strong>and</strong> water. The ratio <strong>of</strong> energy input toprotein output under such a system was poor. Animal proteinwas only 1.4 more nutritious for humans than a comparableamount <strong>of</strong> plant protein, yet consumed 11 times more fossilfuels. Further, feed ingredients were varied <strong>and</strong> included suchitems as dying <strong>and</strong> diseased animals, fecal material fromother factory farmed animals, blood, feathers <strong>and</strong> hair, <strong>and</strong>plastics, which had already led to health scares such asbovine spongiform encephalopathy (‘mad cow disease’). DrKanaly argued that as world per capita incomes <strong>and</strong> rates <strong>of</strong>urbanization grow, the true costs <strong>of</strong> cheap meat <strong>and</strong> theethics <strong>of</strong> this sort <strong>of</strong> food production need to be seriouslyexamined, since both translate into an increased dem<strong>and</strong> foranimal products.Pr<strong>of</strong> Abhik Gupta noted that energy subsidies for all kinds<strong>of</strong> food, even vegetables, were enormous in some countries,<strong>and</strong> mentioned the trend <strong>of</strong> ‘cage-free’ or ‘free-range’ meat inthe US. Dr Kanaly agreed that it was a small movement, atleast in some parts <strong>of</strong> the US, but as consumers grew moreaware <strong>of</strong> livestock conditions producers were potentiallychanging their public face rather than actual practices. Hecited an example <strong>of</strong> an egg farm in South Carolina owned byCatholic monks who used imagery <strong>of</strong> care to sell their eggseven though the operation was basically a factory farm. It wasvery difficult for consumers to get accurate information aboutthe sources <strong>of</strong> their food <strong>and</strong> how animals are treatedbecause the industry was very reluctant to divulge it.Pr<strong>of</strong> Abhik Gupta from India presented a paper on theneed for application <strong>of</strong> the precautionary principle withregards to the mass cultivation <strong>of</strong> biodiesel-yielding plants inbiodiversity-rich areas. Being biodegradable <strong>and</strong> nonpolluting,increasing use <strong>of</strong> biodiesel was expected to reducecarbon dioxide emissions <strong>and</strong> was seen by many as a ‘winwinproposition’ towards meeting the energy requirements<strong>and</strong> providing livelihood opportunities in the denselypopulated <strong>Asian</strong> countries. Pr<strong>of</strong> Gupta argued, however, thathasty <strong>and</strong> indiscriminate plantation <strong>of</strong> biodiesel-yielding plantsin Asia, especially in its biodiversity-rich areas, was fraughtwith environmental <strong>and</strong> ethical concerns. In his home country<strong>of</strong> India, the biodiesel crop jatropha was being aggressivelypromoted by government <strong>and</strong> industry for an area in theNorth-East recognized as a Biodiversity Hot Spot, <strong>and</strong> inMalaysia <strong>and</strong> Indonesia, oil palm plantations were usurpingtropical forests. Features such as invasive potential, toxicity,<strong>and</strong> effects on water <strong>and</strong> soil content were not being fullyassessed in bi<strong>of</strong>uel proposals. Pr<strong>of</strong> Gupta suggested thatbi<strong>of</strong>uels be made one <strong>of</strong> the foci <strong>of</strong> the project, <strong>and</strong> thatparticipants or partners could consider building a database onthe different facets <strong>of</strong> bi<strong>of</strong>uels, especially biodiesels, in orderto be able to make an informed assessment.Pr<strong>of</strong> Gupta was asked about the need for high usage <strong>of</strong>fertilizers on bi<strong>of</strong>uel crops, given that there had beenproblems with the soil for Indian jatropha plantations. Heagreed this was a problem, mentioning a study done by the<strong>International</strong> Crops Research Institute for the Semi-AridTropics (ICRISAT) in India which found that jatropha plantedon marginal l<strong>and</strong> will grow, but without fertilizer <strong>and</strong> labourintensivecanopy management it will not produce seeds,which are the valuable part <strong>of</strong> the crop. He questionedwhether farmers would be able to meet these conditions orwhether jatropha might lead to further l<strong>and</strong> degradation <strong>and</strong>rural indebtedness. Dr N. Manohar wondered if jatropha mightrepresent a similar scenario to the planting <strong>of</strong> eucalyptus inIndia in the 1960s <strong>and</strong> 70s, which had negative environmentalimpacts because it lowered the water table. Were there, heasked, site-specific environmental impact assessments donein planning jatropha plantations? Regarding the toxicity <strong>of</strong>jatropha, he remembered it being used during his childhooddays as fencing material, as cattle never grazed it <strong>and</strong> peoplenever touched it. Pr<strong>of</strong> Gupta agreed that eucalyptus wasdamaging, <strong>and</strong> that site-specific assessments were needed toavoid a similar dem<strong>and</strong> on underground water resources byjatropha, as was already happening with jatropha in otherparts <strong>of</strong> the world. Huge monocultures would always bringecological problems, <strong>and</strong> he felt it essential that legal limits beplaced on any kind <strong>of</strong> monoculture. There also needed to beawareness campaigns, particularly for farmers.An additional comment came from Ms TanujaBhattacharajee on consideration <strong>of</strong> the issue <strong>of</strong> food securityas a consequence <strong>of</strong> energy crop plantations. The export <strong>of</strong>bi<strong>of</strong>uel may result in the import <strong>of</strong> food which could have asevere impact at the national level, particularly in countriesthat are poor such as Bangladesh or Myanmar. She felt,therefore, that it was not a global solution to encourage orcompel bi<strong>of</strong>uel plantation without analyzing the long-termsocio-economic benefit.These papers were followed by the first working groupsessions <strong>of</strong> the meeting.The final day <strong>of</strong> the conference, 28 September, beganwith the session on Energy independence <strong>and</strong> security. DrSalil Sen <strong>of</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong> spoke on ‘Green advertising: Greensupply chain - CSR driven retailing <strong>and</strong> logistics’. Theconfiguration <strong>and</strong> context <strong>of</strong> business at the global level wastransforming, with a growing need for sustainability coupledwith growth. Intensified competition, consumer expectations,<strong>and</strong> the natural resource crunch were driving corporateleadership to synthesize their corporate social responsibilitieswith corporate strategies. There were some tensions,however, between the imperatives for developing renewable<strong>and</strong> bi<strong>of</strong>uel resources, <strong>and</strong> the imperatives for advertising <strong>and</strong>promoting high energy consumption luxury products.Pr<strong>of</strong> On-Kwok Lai asked how Dr Sen saw the future forcommunications in terms <strong>of</strong> green messages, in how theproducts related to the user <strong>and</strong> producer, which both affectthe extent <strong>of</strong> the environmental problem. Dr Sen replied thatthe product was taking a back seat now <strong>and</strong> it was serviceswhich were emerging. People were concerned about theirown health, about societal health <strong>and</strong> about the sustainability<strong>of</strong> our planet.Dr Jasdev Singh Rai from the United Kingdom spoke on‘Concepts <strong>of</strong> communities, energy security <strong>and</strong>independence’. He outlined three essential concepts thatdefine the relationships between communities, energy <strong>and</strong>their environment: anthropocentric systems which hold thathuman beings are at the centre <strong>of</strong> God’s design (Abrahamiccultures); ecocentric systems which hold that human beingsare only one life form in the universe (Eastern <strong>and</strong> otherphilosophies); <strong>and</strong> post-enlightenment scientific systems withconfidence in human reason to solve every possible problem(modernity). States <strong>and</strong> communities <strong>of</strong>ten view energy fromdifferent perspectives – the state from the rational <strong>and</strong> thecommunity from other views rooted in past traditions. Energysecurity <strong>and</strong> energy independence were sources <strong>of</strong> increasingconflict in the international community, for example, in thecase <strong>of</strong> Iran. Dr Rai suggested that there was a need toextend the m<strong>and</strong>ate <strong>of</strong> the <strong>International</strong> Energy Agency togive it a greater role in setting up secure energy resourcesupplies between countries. There could be internationalsupervision, or even international ownership <strong>of</strong>, nuclear powerplants <strong>and</strong> nuclear technologies. Plural outlooks would bestengage marginalised communities. The internationalcommunity should move away from universal conventions<strong>and</strong> declarations to multiple systems which are rooted inregional cultures.Dr Ayoub Aby-Dayyeh took issue with some comments <strong>of</strong>Dr Rai about the history <strong>of</strong> the relationship between Islam <strong>and</strong>science, which Dr Rai later clarified. He was also critical <strong>of</strong> DrRai’s questioning <strong>of</strong> our commitment to prolong the humanlifespan at all costs. He felt that population growth, rather thanlengthening the life <strong>of</strong> human beings, was the waste <strong>of</strong>energy. Dr Rai suggested that longer lives <strong>and</strong> increased

10<strong>Eubios</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Bioethics</strong> 18 (January 2008)births were both types <strong>of</strong> population growth, <strong>and</strong> even inaffluent countries with low birth rates, the energy that wasinvested in bringing up a child was enormous. As a medicaldoctor, he saw old people in hospitals, <strong>and</strong> the amount <strong>of</strong>energy that was needed to keep them surviving was alsoenormous. While he was not suggesting terminating theirlives, he argued that these were problems we had notaddressed in our quest to live longer, healthier lives.Dr Md. Fakrul Islam from Bangladesh spoke on the‘Trend <strong>of</strong> using fossil fuel for irrigation purposes: A case study<strong>of</strong> the Teesta Barrage Target Area, Bangladesh’. Megairrigation projects in Bangladesh <strong>and</strong> India drew on ancientwater cycles between the Himalayas <strong>and</strong> the Bay <strong>of</strong> Bengal.Water flow had been decreasing in recent years, however,<strong>and</strong> farmers were increasingly relying on diesel-poweredwells to extract groundwater to irrigate their crops. As a result,the use <strong>of</strong> imported fossil fuels in Bangladeshi agriculture wasincreasing, <strong>and</strong> as global prices for these commodities rosemany farmers were at risk <strong>of</strong> poverty. Dr Islam raisedconcerns about the impacts <strong>of</strong> extracting groundwater on alarge scale when health, hygiene, income <strong>and</strong> employmentlevels did not appear to be improved. He suggested thatregional cooperation, for example, bilateral treaties betweenIndia <strong>and</strong> Bangladesh, was needed to secure water <strong>and</strong>energy sources, <strong>and</strong> to protect the environment.In discussion, Dr Nguyen Hoang Tri suggested thatsimilar problems could be found in the Mekong Delta also,<strong>and</strong> what happened in Bangladesh to avert flooding wherethere were no barrages. Dr Islam said that embankmentscould be built to protect river banks, although it wasexpensive. Constructing reservoirs was another option,although the area he had been discussing was unsuitable forthis as it was flat. Dr Abhik Gupta made the comment thatmodern international flood management was going againstbuilding embankments, <strong>and</strong> they had proved ineffective inAssam. He suggested that the reality was that these areaswere flood-prone, <strong>and</strong> that rather than flood control, weneeded to think about flood management to reduce thehuman misery caused by flooding. Dr Islam explained thathis preferred solution was not flood control, but an economicsolution that optimized water sharing between India <strong>and</strong>Bangladesh.As the last speaker for the conference, Dr Ir. Khin Ni NiThein from Myanmar spoke on ‘Sustainable hydropower <strong>and</strong>engineering ethics: A quest for a two in one solution’, drawingon her previous advisory position to the World Commission onDams <strong>and</strong> her current position as Vice President forDevelopment <strong>and</strong> Resources at the <strong>Asian</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong>Technology (AIT). She said there were enormous ethicalissues linked to water resources. The world’s richest peopleconsumed the most, while a billion poor people still had noready access to drinking water; they <strong>of</strong>ten have to buy theirwater from vendors at a price which is 10 to 20 times higherthan water sold through the regular distribution network.Dams raised a particular set <strong>of</strong> issues. Whereas in the past,debate had focused on whether dams should be built at all,dams were gradually being recognised as being aboutdevelopment strategies <strong>and</strong> choices, <strong>and</strong> the focus hadshifted to how to build sustainable dams. AIT was currentlyconducting research <strong>and</strong> providing education on sustainablehydropower that included engineering ethics <strong>and</strong> corporatesocial responsibility. Five sustainability measures wereproposed: technical, economical, societal, ethical, <strong>and</strong>environmental.Dr Tavivat Puntarigvivat asked about how we might goabout achieving more equality in access to water. Dr Theinreplied that there were many actors working for waterequality, including the United Nations, NGOs, CSOs <strong>and</strong>global water partnerships which went into regions <strong>and</strong> formedwater user groups so that people could manage their ownwater. It was an uphill battle, however, because a growingnumber <strong>of</strong> companies selling water believed that water was acommodity to be bought <strong>and</strong> sold for pr<strong>of</strong>it, whereas shebelieved water was a human right. Dr Alastair Gunn asked aquestion about teaching engineering ethics <strong>and</strong> how it couldbe incorporated into degree structures. Dr Thein said that shecould only speak for the <strong>Asian</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology, <strong>and</strong>that they were integrating ethical issues into course materials,for example, their course on sustainable hydropower. Ideallythey would like to develop a specialist unit on engineeringethics that could be <strong>of</strong>fered as an elective. At the moment,however, they were <strong>of</strong>fering guest lecturers <strong>and</strong> seminars tostudents in engineering <strong>and</strong> other courses on campus, suchas gender studies, management, <strong>and</strong> environmentalresources.The remainder <strong>of</strong> the day was spent in working groupmeetings on subtopics to develop activity plans in parallelgroups, interspersed with plenary sessions for generalfeedback.Working group reportsThe working group report on Interregionalphilosophical dialogue <strong>and</strong> ecocentric world views,environmental rights <strong>and</strong> timeframes was presented by therapporteur, Pr<strong>of</strong> Alastair Gunn. They raised some preliminaryquestions including: should the term be intercultural ratherthan interregional? This was because regions are simplygeographical groupings, whereas dialogues between differentcultures are both meaningful <strong>and</strong> urgently needed. Culturesshape values in a way that regions don’t. However, theimportant thing is for people to seek common ground thoughdialogue. The group described the United Nations’ ideologyas universalistic. But genuine dialogue between people fromdifferent cultures, with different worldviews <strong>and</strong> different (orno) religions implies a pluralistic position with respect fordifferent ethical positions as genuine alternatives.The group then discussed universalism <strong>and</strong>multiculturalism, <strong>and</strong> why UNESCO needed to change itsorientation if it is to achieve the goals implied in the topic. Thistopic is fundamentally about values. There are many views onthe source <strong>of</strong> values, such as religion, authority, reason orintuition. The group took the view that the values that peopleactually hold <strong>and</strong> live by are best seen as a product <strong>of</strong> culture.What are claimed in UN documents to be universalvalues are <strong>of</strong>ten a historical derivation from theAbrahamic/Christian tradition through the EuropeanEnlightenment <strong>and</strong> Modernism, which seem to have beenadopted without argument. According to one group member,they have even formed the basis for documents such as theIndian Constitution, which has few roots in the philosophy thathas been the basis <strong>of</strong> Indian society for thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> years,for example.A universalistic approach ignores people’s attachment totheir cultures. The group thought that ordinary people did notthink in such terms. The UN could be said to have helped topave the way for globalization by encouraging the view thatethics is concerned with universal values. Globalizing forces<strong>of</strong>ten dwarf <strong>and</strong> squeeze out local values.Nation states are not necessarily representatives <strong>of</strong> anysets <strong>of</strong> values because many are not directly represented.Typically, even in participatory democracies, policies thatstates will advance in the UN are not the subject <strong>of</strong> dialogue.The example <strong>of</strong> Indian philosophy was taken as aworldview. Indian philosophy was an example <strong>of</strong> a source <strong>of</strong>ecocentric values, whereas UN values focus on individualrights which are not a good basis for ecocentrism.Philosophical traditions are the basis <strong>of</strong> ways <strong>of</strong> life in Asia.The texts <strong>of</strong> the Vedas <strong>and</strong> Upanishads are the basis <strong>of</strong>Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, <strong>and</strong> Sikhism. Karma is animportant principle which could be described as universalorder based on law <strong>of</strong> cause <strong>of</strong> effect (Newton’s SecondLaw). It reminds us that our environmental behaviour willreturn to haunt us. Another relevant principle is Dharma,which is duty <strong>and</strong> righteousness. Nature is sacred, for