Status of Caribbean coral reefs after bleaching and hurricanes in 2005

Status of Caribbean coral reefs after bleaching and hurricanes in 2005

Status of Caribbean coral reefs after bleaching and hurricanes in 2005

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Stat u s o fCa r i b b e a nCo r a l Re e f sa f t e rBl e a c h i n ga n dHu r r i c a n e s<strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>Ed i t e d b y Cl i v e Wi l k i n s o na n d Dav i d So u t e r

Stat u s o fCa r i b b e a nCo r a l Re e f sa f t e rBl e a c h i n ga n dHu r r i c a n e s<strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>Ed i t e d b y Cl i v e Wi l k i n s o na n d Dav i d So u t e r

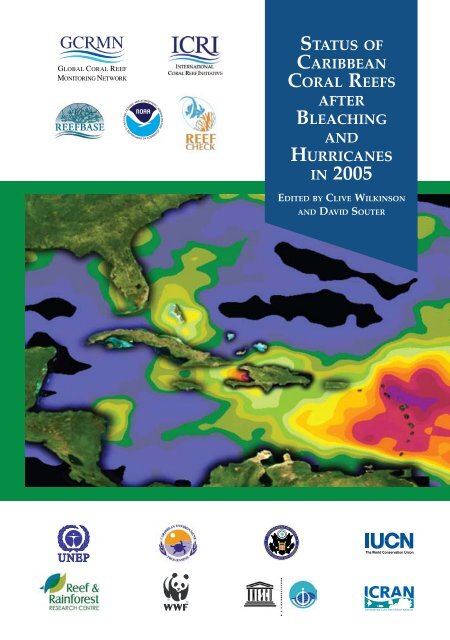

Dedication: This book is dedicated to the many people who have worked on <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> to underst<strong>and</strong> them <strong>and</strong>ensure that they exist for future generations. One <strong>of</strong> these deserves special mention; Len Muscat<strong>in</strong>e retired fromUCLA to his v<strong>in</strong>eyard but did not have enough time to enjoy the fruit <strong>of</strong> his v<strong>in</strong>es. We miss him. The book is alsorecognises the International Coral Reef Initiative <strong>and</strong> partners, <strong>and</strong> particularly those people <strong>in</strong> the USA, operat<strong>in</strong>gthrough the US Coral Reef Task Force, the US Department <strong>of</strong> State <strong>and</strong> the US National Oceanic <strong>and</strong> AtmosphericAdm<strong>in</strong>istration, who cont<strong>in</strong>ue to strive for greater recognition <strong>of</strong> the problems fac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>and</strong> the need forurgent conservation efforts.Note: The conclusions <strong>and</strong> recommendations <strong>of</strong> this book are solely the op<strong>in</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> the authors <strong>and</strong> contributors <strong>and</strong>do not constitute a statement <strong>of</strong> policy, decision, or position on behalf <strong>of</strong> the participat<strong>in</strong>g organizations.Front Cover: A stylized map <strong>of</strong> the maximum Degree Heat<strong>in</strong>g Week values observed across the <strong>Caribbean</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g<strong>2005</strong>, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g the highest level <strong>of</strong> accumulated thermal stress at each location (image from US National Oceanic<strong>and</strong> Atmospheric Adm<strong>in</strong>istration Coral Reef Watch).Inside Title Page: This image shows the <strong>2005</strong> maximum Degree Heat<strong>in</strong>g Week data used to create the image on thefront cover, show<strong>in</strong>g the maximum level <strong>of</strong> accumulated thermal stress at each location (expla<strong>in</strong>ed on pages 38 <strong>and</strong>39; image from US National Oceanic <strong>and</strong> Atmospheric Adm<strong>in</strong>istration Coral Reef Watch).Back Cover: A NOAA/Biogeography Branch diver with a 1 metre by 1 metre quadrat exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a bleachedMontastraea colony at St Croix, US Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s (photo from NOAA Center for Coastal Monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> AssessmentBiogeography Branch).Maps were provided by UNEP-WCMC through ReefBase, The WorldFish Center; we thank them.Citation: Wilk<strong>in</strong>son, C., Souter, D. (2008). <strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>hurricanes</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>.Global Coral Reef Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Network, <strong>and</strong> Reef <strong>and</strong> Ra<strong>in</strong>forest Research Centre, Townsville, 152 p.© Global Coral Reef Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Networkc/o Reef <strong>and</strong> Ra<strong>in</strong>forest Research Centre,PO Box 772Townsville, 4810 AustraliaTelephone: +61 7 47212699;Facsimile: +61 7 47722808www.gcrmn.orgISSN 1447 6185ii

Co n t e n t sAcknowledgementsivForeword 1Executive Summary 31. Introduction 152. Coral Reefs <strong>and</strong> Climate Change: Susceptibility <strong>and</strong> Consequences 193. Hurricanes <strong>and</strong> their effects on Coral Reefs 314. The <strong>2005</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g event: Coral-list Log 375. <strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Mesoamerican Reef <strong>after</strong> the <strong>2005</strong> Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g Event 456. Coral Reefs <strong>of</strong> the U.S. <strong>Caribbean</strong>The History <strong>of</strong> Massive Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> other Perturbations<strong>in</strong> the Florida Keys 61Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the U.S. Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong> <strong>and</strong> 2006 687. The Effects <strong>of</strong> Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Northern <strong>Caribbean</strong><strong>and</strong> Western Atlantic 738. <strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>of</strong> the Lesser Antilles <strong>after</strong> the <strong>2005</strong>Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g Event 859. The Effects <strong>of</strong> Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Southern Tropical America:Brazil, Colombia, <strong>and</strong> Venezuela 10510. Manag<strong>in</strong>g for Mass Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g Strategies for Support<strong>in</strong>gSocio-ecological Resilience 11511. Predictions for the Future <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong> 12912. Sponsor<strong>in</strong>g Organisations, Coral Reef Programs <strong>and</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Networks 13513. Suggested Read<strong>in</strong>g 14514. List <strong>of</strong> Acronyms 148iii

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>Ac k n o w l e d g e m e n t s, Co-s p o n s o r s a n d Supporters o f GCRMNMuch <strong>of</strong> the material for this book was provided voluntarily by more than 70 contributors; we wish to specifically thankthem for their efforts <strong>and</strong> dedication towards conserv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>. Many scientific papers <strong>and</strong> reports were consulted toextract data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation; unfortunately we are unable to <strong>in</strong>clude all <strong>of</strong> these, but have added a number <strong>of</strong> references <strong>in</strong> eachchapter <strong>and</strong> at the back as Suggested Read<strong>in</strong>g. We apologise if pert<strong>in</strong>ent material has not been cited. This report will be lodgedon ReefBase, at WorldFish Center, which acts as the global <strong>coral</strong> reef database, www.reefbase.org. Many colleagues assisted us asreviewers <strong>of</strong> text; we wish to thank these people for their time, effort <strong>and</strong> patience: Robert Buddemeier, Greg Connor, Christ<strong>in</strong>eDawson, Carlos Drews, Simon Donner, Scot Frew, Robert G<strong>in</strong>sburg, Stefan Ha<strong>in</strong>, Marea Hatziolos, Jim Hendee, Scott Heron,Gregor Hodgson, Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Maria Hood, Christy Loper, Derek Manzello, Peter Mumby, Bernard Salvat, KristianTeleki, Aless<strong>and</strong>ra Vanzella-Khouri <strong>and</strong> Christian Wild. We specifically thank Fiona Alongi <strong>and</strong> Tim Harvey for formatt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>edit<strong>in</strong>g; others also assisted us <strong>in</strong> unseen ways – thanks.Three operational partners <strong>of</strong> the GCRMN have assisted with this report: Gregor Hodgson <strong>and</strong> Cori Kane <strong>of</strong> the Reef CheckFoundation; Jamie Oliver, Stanley Tan <strong>and</strong> Moi Khim Tan <strong>of</strong> ReefBase; Christy Loper <strong>of</strong> NOAA who coord<strong>in</strong>ates the SocioeconomicMonitor<strong>in</strong>g Network; <strong>and</strong> colleagues. The Management Group <strong>of</strong> the GCRMN has provided substantial assistance, advice <strong>and</strong>support: The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission <strong>of</strong> UNESCO; the United Nations Environment Programme CoralReef Unit (UNEP-CRU); IUCN - The World Conservation Union; the World Bank; the Convention on Biological Diversity;WorldFish Center; <strong>and</strong> the ICRI Secretariat, held by Mexico <strong>and</strong> USA. These meet voluntarily to provide guidance to the GCRMN.Direction for the GCRMN Management Group has been provided Carl Gustaf Lund<strong>in</strong> (Chair), <strong>and</strong> the GCRMN Chair <strong>of</strong> theScientific <strong>and</strong> Technical Advisory Committee, Bernard Salvat, assisted with manuscripts <strong>and</strong> advice on the format <strong>and</strong> structure<strong>of</strong> the report - we thank them all. The host <strong>of</strong> the GCRMN, the Reef <strong>and</strong> Ra<strong>in</strong>forest Research Centre is specifically thanked.Support for the GCRMN primarily comes from the US Department <strong>of</strong> State <strong>and</strong> the National Oceanic <strong>and</strong> AtmosphericAdm<strong>in</strong>istration via funds channelled through UNEP <strong>in</strong> Cambridge, The Hague <strong>and</strong> Nairobi. This support is critical for theoperation <strong>of</strong> the GCRMN <strong>and</strong> the publication <strong>of</strong> this <strong>Caribbean</strong> status report; thus special thanks go to those people <strong>in</strong>volved. Wereceived funds to produce, pr<strong>in</strong>t <strong>and</strong> distribute this book from: the Government <strong>of</strong> the USA (Department <strong>of</strong> State <strong>and</strong> NOAA);IUCN - The World Conservation Union; the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); WWF International, especially the<strong>of</strong>fices <strong>in</strong> Europe; the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission <strong>of</strong> UNESCO; Reef Check <strong>and</strong> the PADI Foundation; RRRC-Reef <strong>and</strong> Ra<strong>in</strong>forest Research Centre; ICRAN <strong>and</strong> the Buccoo Reef Trust. Their assistance ensures that the book will be produced<strong>and</strong> provided free <strong>of</strong> charge to people around the world who are work<strong>in</strong>g to conserve <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>, <strong>of</strong>ten voluntarily.GCRMN Management GroupIOC-UNESCO –Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission <strong>of</strong> UNESCOUNEP – United Nations Environment ProgrammeIUCN – The World Conservation Union (Chair)The World Bank, Environment DepartmentCBD – Convention on Biological DiversityAIMS – Australian Institute <strong>of</strong> Mar<strong>in</strong>e ScienceGBRMPA – Great Barrier Reef Mar<strong>in</strong>e Park AuthorityRRRC – Reef <strong>and</strong> Ra<strong>in</strong>forest Research Centre (host)WorldFish Center <strong>and</strong> ReefBaseICRI Secretariat – Governments <strong>of</strong> USA <strong>and</strong> MexicoGCRMN Scientific <strong>and</strong> Technical Advisory Committee.GCRMN Operational PartnersReef Check Foundation, Los AngelesReefBase, WorldFish Center, PenangCORDIO – Coral Reef Degradation <strong>in</strong> the Indian OceanWorld Resources Institute, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton DCNOAA – Socioeconomic Assessment group, Silver Spr<strong>in</strong>gs.Major F<strong>in</strong>ancial Supporters* <strong>and</strong> other Supporters <strong>of</strong> this report* The Government <strong>of</strong> the USA, through the US Department <strong>of</strong> State, <strong>and</strong>* NOAA – National Oceanic <strong>and</strong> Atmospheric Adm<strong>in</strong>istration* UNEP – United Nations Environment Programme via USA counterpart fundsICRAN International Coral Reef Action Network (ICRAN) <strong>and</strong> Buccoo Reef Trust TobagoIOC-UNESCO - Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission <strong>of</strong> UNESCOIUCN – the World Conservation Union, Gl<strong>and</strong> Switzerl<strong>and</strong>PADI Foundation <strong>and</strong> Reef Check, Los Angeles, USAWWF – Europeiv

Fo r e w o r dHere <strong>in</strong> 2008, we are <strong>in</strong> the midst <strong>of</strong> the International Year <strong>of</strong> the Reef as designated by theInternational Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI). This year-long campaign <strong>of</strong> events <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiatives isaimed at promot<strong>in</strong>g conservation action <strong>and</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g long-term partnerships for susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>coral</strong> reef systems.1992 was also a critical year for the world’s environment. World leaders met <strong>in</strong> Rio de Janeiroat the United Nations Conference on Environment <strong>and</strong> Development (UNCED) to sign theConvention on Biological Diversity <strong>and</strong> also pledge major resources for environmental action.The Rio Conference also led to negotiations that transformed the Global Environment Facility(GEF) from a pilot program to a permanent f<strong>in</strong>ancial mechanism <strong>in</strong> support <strong>of</strong> the globalenvironment. Estimates were also made <strong>in</strong> 1992 that the world had already lost 10% <strong>of</strong> the <strong>coral</strong><strong>reefs</strong> <strong>and</strong> that a further 60% were under threat <strong>of</strong> destruction if urgent actions to implementsusta<strong>in</strong>able use <strong>and</strong> conservation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>reefs</strong> were not implemented. In the 16 years s<strong>in</strong>cethese estimates were made at the 7th International Coral Reef Symposium <strong>in</strong> Guam, alarm<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> degradation <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> have been reported.The events <strong>of</strong> 1992 catalyzed the formation <strong>of</strong> the ICRI as well as the Global Coral Reef Monitor<strong>in</strong>gNetwork (GCRMN), which has supported production <strong>of</strong> this book. Chapter 17 <strong>of</strong> Agenda 21that was agreed at UNCED highlighted that <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> warranted special attention. This wasre-affirmed at the World Summit on Susta<strong>in</strong>able Development <strong>in</strong> 2002 <strong>in</strong> Johannesburg, whichalso provided an <strong>in</strong>centive for countries to work with the GEF to conserve valuable mar<strong>in</strong>eresources. The Johannesburg Summit urged that small countries be given additional assistanceto: adopt <strong>in</strong>tegrated approaches for watershed, coastal <strong>and</strong> mar<strong>in</strong>e management; recognisetraditional knowledge <strong>and</strong> management methods; <strong>in</strong>crease the <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>of</strong> communities<strong>and</strong> the private sector <strong>in</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>; improve their capacity to monitor, conserve <strong>and</strong>susta<strong>in</strong>ably manage <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>and</strong> associated ecosystems; <strong>and</strong> create representative networks<strong>of</strong> mar<strong>in</strong>e protected areas for the conservation <strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>, mangroveforests <strong>and</strong> seagrass areas.The GEF attaches critical importance to the health <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> as nearly 500 million peopleacross the world depend on them for food, coastal protection, livelihoods, <strong>and</strong> tourism <strong>in</strong>come.This <strong>in</strong>cludes about 30 million particularly poor people who depend almost entirely on <strong>coral</strong><strong>reefs</strong> for food <strong>and</strong> protection. The agenda for <strong>coral</strong> reef conservation <strong>in</strong> 1992 focused onmanag<strong>in</strong>g the impacts <strong>of</strong> coastal communities through a new focus on susta<strong>in</strong>able development<strong>of</strong> these resources. Management efforts were aimed at reduc<strong>in</strong>g the impacts from the l<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>excess sediment flows from poor l<strong>and</strong> use, nutrient pollution from human, agricultural <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>dustrial wastes, as well as over-exploitation <strong>and</strong> damag<strong>in</strong>g fish<strong>in</strong>g practices, <strong>and</strong> damag<strong>in</strong>gmodification <strong>of</strong> shorel<strong>in</strong>es.1

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>`But that agenda changed <strong>after</strong> 1998 dur<strong>in</strong>g the large El Niño <strong>and</strong> La Niña shift <strong>in</strong> the globalclimate that resulted <strong>in</strong> massive <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>. Approximately 16% <strong>of</strong> the world’s <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>died <strong>in</strong> 1998 with especially severe damage <strong>in</strong> the Indian Ocean <strong>and</strong> Western Pacific. All <strong>of</strong> us<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> conservation had to focus on the emerg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g threat that global climatechange br<strong>in</strong>gs to <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> with stressful temperatures, ris<strong>in</strong>g sea levels, <strong>and</strong> threaten<strong>in</strong>g theability <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s to survive <strong>in</strong> potentially more acidic waters.Another significant event related to <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> occurred <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>. This book, <strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>, documents the devastat<strong>in</strong>g effects on<strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> from the hottest year on record with its very high sea surface temperatures <strong>and</strong>record hurricane activity throughout the <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>and</strong> Atlantic bas<strong>in</strong>s. The development <strong>of</strong>this report has brought together 71 <strong>coral</strong> reef scientists <strong>and</strong> managers, predom<strong>in</strong>antly fromdevelop<strong>in</strong>g countries, to catalogue the impacts <strong>of</strong> the warm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> storms dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>2005</strong> <strong>and</strong>subsequently <strong>in</strong> 2006.This detailed <strong>in</strong>formation is valuable for environmental managers <strong>and</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g agencies tounderscore urgent actions needed to assist <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>in</strong> recovery by focus<strong>in</strong>g on natural resistance<strong>and</strong> resilience as well as remov<strong>in</strong>g threats posed by human activities that slow or even preventrecovery from these damag<strong>in</strong>g events. More importantly, these f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are particularly criticalfor the peoples <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong> who are highly dependent on these <strong>coral</strong> reef resources forprovid<strong>in</strong>g natural defences <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> coastal protection aga<strong>in</strong>st storms <strong>and</strong> a buffer aga<strong>in</strong>stsea level rise. Healthy <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> also cont<strong>in</strong>ue to provide food <strong>and</strong> family <strong>in</strong>come, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gtropical tourism.Last year, the GEF launched a series <strong>of</strong> new programmatic approaches to support many <strong>of</strong> theSmall Isl<strong>and</strong> Develop<strong>in</strong>g States (SIDS). I had the privilege with Heads <strong>of</strong> State <strong>and</strong> top government<strong>of</strong>ficials from Pacific Isl<strong>and</strong> Countries to announce a new type <strong>of</strong> GEF programmatic approachtoward susta<strong>in</strong>able development <strong>of</strong> isl<strong>and</strong>s. Known as the Pacific Alliance for Susta<strong>in</strong>ability,the program supports a number <strong>of</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ked GEF operations address<strong>in</strong>g biological diversity,climate change mitigation <strong>and</strong> adaptation, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrated approaches toward l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> waterresources management. This new approach comes on the heels <strong>of</strong> successful GEF projectsfor the <strong>Caribbean</strong> such as the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System Project <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>markGEF Coral Reef Targeted Research <strong>and</strong> Capacity Build<strong>in</strong>g project that is work<strong>in</strong>g through aCenter <strong>of</strong> Excellence <strong>in</strong> Mexico <strong>and</strong> others globally <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries to f<strong>in</strong>d solutions toimprove <strong>coral</strong> reef management to susta<strong>in</strong> these valuable ecosystems.Throughout the years I have developed a deep appreciation <strong>of</strong> the traditions <strong>and</strong> the reliance <strong>of</strong>isl<strong>and</strong> communities on the <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>and</strong> lagoons. For those who also have <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> thesecritically important systems, I recommend this report on the <strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs<strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong> <strong>and</strong> ask you to jo<strong>in</strong> the global effort to conserve ourplanet’s <strong>coral</strong> reef systems.Monique BarbutChair <strong>and</strong> Chief Executive OfficerGlobal Environment Facility2

Ex e c u t i v e Su m m a r yCl i v e Wilk<strong>in</strong>son a n d Dav i d So u t e r<strong>2005</strong> – a hot yearzx <strong>2005</strong> was the hottest year <strong>in</strong> the Northern Hemisphere on average s<strong>in</strong>ce the advent<strong>of</strong> reliable records <strong>in</strong> 1880.zx That year exceeded the previous 9 record years, which have all been with<strong>in</strong> the last15 years.zx <strong>2005</strong> also exceeded 1998 which previously held the record as the hottest year; therewere massive <strong>coral</strong> losses throughout the world <strong>in</strong> 1998.zx Large areas <strong>of</strong> particularly warm surface waters developed <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>and</strong>Tropical Atlantic dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>2005</strong>. These were clearly visible <strong>in</strong> satellite images asHotSpots.zx The first HotSpot signs appeared <strong>in</strong> May, <strong>2005</strong> <strong>and</strong> rapidly exp<strong>and</strong>ed to cover thenorthern <strong>Caribbean</strong>, Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico <strong>and</strong> the mid-Atlantic by August.zx The HotSpots cont<strong>in</strong>ued to exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensify until October, <strong>after</strong> which w<strong>in</strong>terconditions cooled the waters to near normal <strong>in</strong> November <strong>and</strong> December.zx The excessive warm water resulted <strong>in</strong> large-scale temperature stress to <strong>Caribbean</strong><strong>coral</strong>s.<strong>2005</strong> – a hurricane yearzx The <strong>2005</strong> hurricane year broke all records with 26 named storms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g 13<strong>hurricanes</strong>.zx In July, the unusually strong Hurricane Dennis struck Grenada, Cuba <strong>and</strong> Florida.zx Hurricane Emily was even stronger, sett<strong>in</strong>g a record as the strongest hurricane tostrike the <strong>Caribbean</strong> before August.zx Hurricane Katr<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> August was the most devastat<strong>in</strong>g storm to hit the USA.It caused massive damage around New Orleans.3

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>zx Hurricane Rita, a Category 5 storm, passed through the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico to strikeTexas <strong>and</strong> Louisiana <strong>in</strong> September.zx Hurricane Wilma <strong>in</strong> October was the strongest Atlantic hurricane on record <strong>and</strong>caused massive damage <strong>in</strong> Mexico, especially around Cozumel <strong>in</strong> Mexico.zx The hurricane season ended <strong>in</strong> December when tropical storm Zeta formed <strong>and</strong>petered out <strong>in</strong> January.zx Many <strong>of</strong> these <strong>hurricanes</strong> caused considerable damage to the <strong>reefs</strong> via wave action<strong>and</strong> run<strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> muddy, polluted freshwater.zx The effects were not all bad. Some <strong>hurricanes</strong> reduced thermal stress by mix<strong>in</strong>gdeeper cooler waters <strong>in</strong>to surface waters.zx Although there were many <strong>hurricanes</strong>, none passed through the Lesser Antilles tocool the waters, where the largest HotSpot persisted.<strong>2005</strong> – a massive <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> eventzx The warm water temperatures caused large-scale <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> as a stress responseto the excessive temperatures.zx Bleached <strong>coral</strong>s were effectively starv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> susceptible to other stresses <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gdiseases; many died as a result.zx The first <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> was reported from Brazil <strong>in</strong> the Southern Hemisphere; butit was m<strong>in</strong>or.zx The first <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> reports <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong> were <strong>in</strong> June from Colombia <strong>in</strong> thesouth <strong>and</strong> Puerto Rico <strong>in</strong> the north.zx By July, <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> reports came <strong>in</strong> from Belize, Mexico <strong>and</strong> the U.S. Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>saffect<strong>in</strong>g between 25% <strong>and</strong> 45% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> colonies.zx By August, the <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> extended to Florida, Puerto Rico, the Cayman Isl<strong>and</strong>s, thenorthern Dutch Antilles (St. Maarten, Saba, St. Eustatius), the French West Indies(Guadeloupe, Mart<strong>in</strong>ique, St. Barthelemy), Barbados <strong>and</strong> the north coasts <strong>of</strong> Jamaica<strong>and</strong> Cuba.zx Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> these countries was generally severe affect<strong>in</strong>g 50% to 95% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>colonies.zx In some countries (e.g. Cayman Isl<strong>and</strong>s) it was the worst <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> ever seen.zx By September, <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> affected the south coast <strong>of</strong> Jamaica <strong>and</strong> the Dom<strong>in</strong>icanRepublic, with 68% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s affected;zx By October, Tr<strong>in</strong>idad <strong>and</strong> Tobago was report<strong>in</strong>g 85% <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the development<strong>of</strong> a second HotSpot was caus<strong>in</strong>g the most severe <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> for the last 25 years;some places reported 100%, although it was highly variable between sites;zx By November, m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> also affected Venezuela, Guatemala <strong>and</strong> the Dutchisl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Bonaire <strong>and</strong> Curacao, affect<strong>in</strong>g 14% to 25% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s.zx In many countries (Cuba, Jamaica, Colombia, Florida, USA) there was great variation<strong>in</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> between sites. In Florida, areas exposed to regular large temperaturefluctuations, <strong>and</strong> nutrient <strong>and</strong> sediment loads were less affected. In the French WestIndies, the variation was attributed to different species composition between sites.4

Executive Summaryzx The <strong>coral</strong>s vulnerable to <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> were similar across the <strong>Caribbean</strong>, particularly:Acropora palmata <strong>and</strong> A. cervicornis, Agaricia, Montastraea, Colpophyllia, Diploria,Siderastrea, Porites, the hydrozoan Palythoa <strong>and</strong> the hydro<strong>coral</strong> Millepora, whichhas nearly disappeared from the French West Indies.zx Bleach<strong>in</strong>g persisted to mid-2006 <strong>in</strong> Guadeloupe, Mart<strong>in</strong>ique, Barbados <strong>and</strong> Tr<strong>in</strong>idad<strong>and</strong> Tobago, <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> 2007 <strong>in</strong> St. Barthelemy. Reefs <strong>in</strong> these countries showed fewsigns <strong>of</strong> recovery, with between 14% <strong>and</strong> 33% <strong>of</strong> colonies still bleached.<strong>2005</strong> – extensive <strong>coral</strong> mortality <strong>and</strong> diseasezx The greatest damage occurred <strong>in</strong> the isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the Lesser <strong>and</strong> Greater Antilles where<strong>coral</strong>s were bathed <strong>in</strong> abnormally warm waters for 4 to 6 months.zx The greatest <strong>coral</strong> mortality occurred <strong>in</strong> the U.S. Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s, which suffered anaverage decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> 51.5% due to <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> subsequent disease; the worst seen <strong>in</strong>more than 40 years <strong>of</strong> observations.zx Barbados experienced the most severe <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> event ever with 17% to 20% <strong>coral</strong>mortality.zx Losses <strong>in</strong> the French West Indies ranged between 11% <strong>and</strong> 30%.zx In the northern Dutch Antilles, there was 18% mortality <strong>in</strong> St. Eustatius, butm<strong>in</strong>imal mortality <strong>in</strong> Bonaire <strong>and</strong> Curacao <strong>in</strong> the south.zx Tr<strong>in</strong>idad <strong>and</strong> Tobago suffered considerable mortality, with 73% <strong>of</strong> all Colpophyllia<strong>and</strong> Diploria colonies dy<strong>in</strong>g.zx Although there was severe <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Greater Antilles, m<strong>in</strong>imal mortalityoccurred <strong>in</strong> Bahamas, Bermuda, Cayman Isl<strong>and</strong>s, Cuba, Jamaica <strong>and</strong> Turks <strong>and</strong> Caicos;some sites <strong>in</strong> the Dom<strong>in</strong>ican Republic, however, suffered up to 38% mortality.zx Bleach<strong>in</strong>g mortality was m<strong>in</strong>imal on the Mesoamerican Reef system, largely becausemany storms cooled sea temperatures; however, Hurricanes Emily <strong>and</strong> Wilmadamaged some <strong>reefs</strong>, decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong> cover from 24% to 10%, especially aroundCozumel.zx Coral mortality <strong>in</strong> Colombia <strong>and</strong> Venezuela was negligible.zx Increased prevalence <strong>of</strong> disease follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> was reported from many isl<strong>and</strong>s<strong>of</strong> the Lesser Antilles, particularly French West Indies; <strong>in</strong>fection rates <strong>in</strong>creased from33% to 39% on Guadeloupe <strong>and</strong> 18% to 23% on St. Barthelemy; 49% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s were<strong>in</strong>fected on Mart<strong>in</strong>ique.zx In Tr<strong>in</strong>idad <strong>and</strong> Tobago, there was clear evidence <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the prevalence <strong>of</strong>disease.zx In the U.S. Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s, secondary disease <strong>in</strong>fections killed bleached colonies <strong>of</strong>Montastraea, Colpophyllia, Diploria <strong>and</strong> Porites.<strong>2005</strong> – lessons for management <strong>and</strong> future optionszx Unfortunately direct management action is unlikely to prevent <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong>mortality from climate change on most <strong>of</strong> the world’s <strong>reefs</strong>.zx However, effective management can reduce the damage from direct human pressures<strong>and</strong> encourage the natural adaptation mechanisms to build up reef resilience;5

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>zx Such actions will promote more rapid recovery <strong>in</strong> the future, especially if <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>will become a regular event.zx Unfortunately, current predictions are for more frequent <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tense warm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the<strong>Caribbean</strong> with the high probability <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>coral</strong> mortality.zx Severe <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is predicted to become a more regular event by 2030, <strong>and</strong> anannual event by 2100, if the current rate <strong>of</strong> greenhouse emissions is not reversed.In t r o d u c t i o nThe most extreme <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> mortality event to hit the Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong> (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gAtlantic) <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> occurred <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>. This was dur<strong>in</strong>g the warmest year ever recorded, eclips<strong>in</strong>gthe 9 warmest years that had occurred s<strong>in</strong>ce 1995. The previous warmest year was 1998,which resulted <strong>in</strong> massive <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> throughout many parts <strong>of</strong> the world <strong>and</strong> effectivelydestroyed 16% <strong>of</strong> the world’s <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>, especially <strong>in</strong> the Indian Ocean <strong>and</strong> Western Pacific.Unlike the events <strong>of</strong> 1998, this climate-related <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> event did not occur <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>formationvacuum; this time there were many scientific tools available <strong>and</strong> alerts issued to thosework<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong> to assess the damage <strong>and</strong> possibly preparemanagement responses to reduce the damage. This book expla<strong>in</strong>s <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> followsthe sequence <strong>of</strong> the events lead<strong>in</strong>g up to it, <strong>and</strong> documents much <strong>of</strong> the damage that occurredto the <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>and</strong> consequently to the people dependent on <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> for their livelihoods<strong>in</strong> the Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong>.This graph from the Hadley Climate Center <strong>in</strong> the UK shows that surface temperatures <strong>in</strong> the NorthernHemisphere have been much higher <strong>in</strong> the last two decades <strong>and</strong> appear to be <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g from thebasel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> temperatures <strong>in</strong> 1960. The red l<strong>in</strong>e is a 10 year runn<strong>in</strong>g average.6

Executive SummaryIt May <strong>2005</strong>, analysis <strong>of</strong> satellite images by the National Oceanic <strong>and</strong> Atmospheric Adm<strong>in</strong>istration(NOAA) <strong>of</strong> USA showed that the waters <strong>of</strong> the Southern <strong>Caribbean</strong> were warm<strong>in</strong>g faster thannormal <strong>and</strong> people <strong>in</strong> the region were asked to look out for <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>. The warm<strong>in</strong>gwas evident as a ‘HotSpot’ <strong>of</strong> warmer water which was likely to stress <strong>coral</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the Northern<strong>Caribbean</strong> (see p. 38).As the surface waters cont<strong>in</strong>ued to heat up, it became obvious that this was go<strong>in</strong>g to be aparticularly stressful year for the <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong>. NOAA issued a regular series <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>formation bullet<strong>in</strong>s, warn<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> alerts on the warm<strong>in</strong>g waters <strong>and</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>hurricanes</strong>,thereby stimulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong> reef managers <strong>and</strong> scientists to exam<strong>in</strong>e their <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> for signs<strong>of</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>. Throughout August, September <strong>and</strong> October it became clear <strong>in</strong> reports from theWider <strong>Caribbean</strong> that <strong>2005</strong> was probably the most severe <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> mortality eventever recorded. The HotSpot warm<strong>in</strong>g reached its peak <strong>in</strong> October <strong>and</strong> then dissipated as w<strong>in</strong>terapproached <strong>and</strong> solar heat<strong>in</strong>g shifted to the southern hemisphere. However, monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>the <strong>coral</strong>s cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong>to 2006 to assess either recovery from <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, or <strong>in</strong>cidences <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>disease or mortality. There were also prelim<strong>in</strong>ary assessments <strong>of</strong> the social <strong>and</strong> economic costs<strong>of</strong> this HotSpot phenomenon.The <strong>2005</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> event has followed a long, slow decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the status <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>over thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> years; especially dur<strong>in</strong>g the last 50 years. Many <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> have lost upto 80% <strong>of</strong> their <strong>coral</strong> cover dur<strong>in</strong>g this time. The causes <strong>in</strong>cluded climate related factors priorto <strong>2005</strong>, but most <strong>of</strong> the <strong>coral</strong> losses were due to direct human impacts such as over-fish<strong>in</strong>g,excess sediment <strong>in</strong>put, <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> nutrients from agriculture <strong>and</strong> domestic sewage, <strong>and</strong>direct damage to <strong>reefs</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g development. These impacts are all symptomatic <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>ghuman populations <strong>and</strong> their use <strong>of</strong> the <strong>reefs</strong>, such that many <strong>of</strong> these occur simultaneously.The damage symptoms are <strong>of</strong>ten seen as particularly low fish populations, outbreaks <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>diseases, or <strong>coral</strong>s struggl<strong>in</strong>g to grow <strong>in</strong> poor quality, dirty waters or smothered by algae. Thusmany <strong>of</strong> the <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong> were already stressed <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e when the majorclimate change events <strong>of</strong> <strong>2005</strong> struck.The isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> countries <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong> are highly dependent on <strong>coral</strong> reefresources, thus there is an urgent need for appropriate management responses as seatemperatures are predicted to <strong>in</strong>crease further <strong>in</strong> future. The World Resources Institute Reefs@Risk analysis estimated that <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2000 provided between US$3,100 millionto $4,600 million each year from fisheries, dive tourism, <strong>and</strong> shorel<strong>in</strong>e protection services;however 64% <strong>of</strong> these same <strong>reefs</strong> were threatened by human activities, especially <strong>in</strong> the Eastern<strong>Caribbean</strong>, most <strong>of</strong> the Southern <strong>Caribbean</strong>, Greater Antilles, Florida Keys, Yucatan, <strong>and</strong> thenearshore parts <strong>of</strong> the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System. All these areas suffered severe<strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> damage <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>. The R@R analysis <strong>in</strong>dicated that <strong>coral</strong> loss could cost the regionUS$140 million to $420 million annually.This book compiles data <strong>and</strong> observations <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> mortality from more than70 <strong>coral</strong> reef workers <strong>and</strong> volunteer divers to summarize the current status <strong>of</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>in</strong> theWider <strong>Caribbean</strong>; but more importantly the book seeks to provide <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>coral</strong> reefmanagers <strong>and</strong> decision makers to aid <strong>in</strong> the search for solutions to arrest the <strong>coral</strong> reef decl<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong> a region that conta<strong>in</strong>s 10.3% <strong>of</strong> the world’s <strong>reefs</strong>. These compiled reports also illustrate thevalue <strong>of</strong> early predictions <strong>of</strong> possible <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>; ‘products’ developed by NOAA from archived7

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong><strong>and</strong> current satellite images, complemented by direct measures like temperature loggers <strong>and</strong>buoys, were used to warn <strong>of</strong> the impend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> threat. The products were distributedwidely through e-mail alerts <strong>and</strong> various <strong>in</strong>ternet sites, alert<strong>in</strong>g natural resource managers <strong>of</strong>the potential for damage to their <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>. Hundreds <strong>of</strong> scientists <strong>and</strong> resource managers <strong>in</strong>the <strong>Caribbean</strong> used these alerts <strong>and</strong> products <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong> to allocate large amounts <strong>of</strong> their limitedf<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>and</strong> logistic resources to monitor what turned out to be a record-break<strong>in</strong>g <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>event. The <strong>in</strong>formation yielded from this monitor<strong>in</strong>g will be vital to future management effortsto protect <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>in</strong> light <strong>of</strong> today’s rapidly chang<strong>in</strong>g climate.Th e <strong>2005</strong> Co r a l Bl e a c h i n g Ev e n t a n d Hu r r i ca n e sThese follow<strong>in</strong>g HotSpot images <strong>and</strong> the other ‘Degree Heat<strong>in</strong>g Week’ images on the front cover<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>side title page are typical <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>formation that was widely dispersed throughout the<strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>and</strong> elsewhere via the Internet through the <strong>coral</strong> reef <strong>in</strong>formation network ‘Coral-List’. This generated considerable correspondence, <strong>and</strong> senior NOAA scientists have <strong>of</strong>feredtheir personal <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>of</strong> what happened <strong>in</strong> their <strong>of</strong>fices as the sequence <strong>of</strong> events developed.These are detailed <strong>in</strong> Chapter 4.This 1st figure illustrates a typical HotSpot image (explanation on p. 38) that was generated fromsatellite data <strong>and</strong> distributed throughout the Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong>. The HotSpot on 16 July <strong>2005</strong> showswaters 1ºC to 2ºC above the normal summer maximum as seen as ‘warm’ yellow <strong>and</strong> orange colorsover central America as well as a large but less warm region <strong>in</strong> the central Atlantic Ocean; as this wasbe<strong>in</strong>g reported there was evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> reported <strong>in</strong> Belize.The first signs <strong>of</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> were <strong>in</strong> Brazil <strong>in</strong> March dur<strong>in</strong>g the southern summer. However,this did not correspond to a major HotSpot; it was more likely due to a local calm weather <strong>and</strong>heat<strong>in</strong>g event. The first <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong> was reported <strong>in</strong> early June on theIslas del Rosario <strong>in</strong> northwest Colombia where waters had warmed to 30 o C. These waters thencooled <strong>and</strong> the <strong>coral</strong>s recovered. By late June, surface waters exceeded 30 o C around Puerto8

Executive SummaryRico, <strong>and</strong> up to 50% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s had already died. There was also <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on the <strong>Caribbean</strong> coast<strong>of</strong> Panama, although this did not result <strong>in</strong> significant mortality.In July, <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> was reported <strong>in</strong> Belize, Mexico, Bahamas <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Bermuda <strong>and</strong> the US Virg<strong>in</strong>Isl<strong>and</strong>s, which also co<strong>in</strong>cided with reports <strong>of</strong> the death <strong>of</strong> large sponges <strong>in</strong> the US Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>f Cozumel <strong>in</strong> Mexico.Although between 25% <strong>and</strong> 45% <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> was reported <strong>in</strong> Belize <strong>and</strong> Mexico, the HotSpotalong the Mesoamerican Reef system dissipated with the regular passage <strong>of</strong> storms dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>2005</strong>,which prevented any significant <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> related mortality. Despite the cool<strong>in</strong>g benefits to theregion, Hurricanes Wilma <strong>and</strong> Emily caused considerable damage to <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>, especially<strong>in</strong> Mexico around the isl<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> Cozumel. Lower mortality <strong>in</strong> the Mesoamerican region maybe attributable to a reduced population <strong>of</strong> temperature sensitive <strong>coral</strong>s, because previous<strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> disease events have removed the more sensitive species. It appears that the moreresistant species were only slightly affected. Coral cover has decreased markedly <strong>in</strong> the past 35years, <strong>in</strong> some cases from near 80% to less than 20%.This image from mid-August shows a dramatic expansion <strong>of</strong> two HotSpots with temperatures 2ºCto 3ºC <strong>in</strong> excess <strong>of</strong> the summer maximum cover<strong>in</strong>g large parts <strong>of</strong> the Northern <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gFlorida, the Flower Garden Banks <strong>in</strong> the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico <strong>and</strong> just touch<strong>in</strong>g Cuba. The HotSpot <strong>in</strong> theAtlantic has exp<strong>and</strong>ed alarm<strong>in</strong>gly to cover all the isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the Lesser Antilles; <strong>and</strong> there is a smallHotSpot over Colombia. Bleach<strong>in</strong>g was be<strong>in</strong>g reported <strong>in</strong> all <strong>of</strong> these regions, as outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> thefollow<strong>in</strong>g chapters.By early August, concern was grow<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> would damage the <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>of</strong> Florida <strong>and</strong>the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico. As the HotSpot exp<strong>and</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the north, there were reports <strong>of</strong> extensive<strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Florida Keys, with water temperatures around 31°C <strong>and</strong> almost totally calm<strong>and</strong> sunny conditions. In late August, extensive <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> co<strong>in</strong>cided with the warmest water9

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>ever recorded on Sombrero Key <strong>in</strong> Florida, but fortunately for these <strong>reefs</strong>, Hurricane Katr<strong>in</strong>apassed through the area as Category 1 storm result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> considerable cool<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the waters(see p. 35).Similarly, <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased around Puerto Rico <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g all <strong>coral</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>coral</strong>-like animalsunder hot calm conditions <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> disease <strong>in</strong>creased alarm<strong>in</strong>gly. Severe<strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, up to 95%, was be<strong>in</strong>g reported from several isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the Greater (Cayman Isl<strong>and</strong>s,Jamaica, Cuba) <strong>and</strong> Lesser Antilles (Guadeloupe, Mart<strong>in</strong>ique, St. Barthelemy <strong>in</strong> the FrenchWest Indies, St. Maarten, Saba, St. Eustatius <strong>in</strong> the northern Dutch Antilles, <strong>and</strong> Barbados).Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Cayman Isl<strong>and</strong>s was the worst ever recorded.By early September, two major HotSpots with sea surface temperatures 2ºC to 3ºC more than normalare cover<strong>in</strong>g Puerto Rico, the Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> the other is still cover<strong>in</strong>g the Lesser Antilles. Theorig<strong>in</strong>al HotSpot over the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico <strong>and</strong> Florida has been effectively ‘blown away’ by Hurricanes,especially Katr<strong>in</strong>a that went on to devastate New Orleans on 29 August <strong>2005</strong> (see the Chapter onHurricanes p. 31). Reports <strong>of</strong> major <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> were received correspond<strong>in</strong>g to all the sites withHotSpots.The weather was particularly calm for two weeks <strong>in</strong> September, <strong>and</strong> was accompanied byextensive <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on the south coast <strong>of</strong> Jamaica where about 80% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s bleached. TheAugust <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> on the north coast <strong>of</strong> Jamaica began to subside. Sea temperatures <strong>in</strong> the U.S.Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s reached more than 30°C at 16 m depth. Bleach<strong>in</strong>g affected most <strong>coral</strong> species.More than 90% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s bleached down to 30 m on the nearby British Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s. Moreextensive <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ued on northern Puerto Rico. The <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> footpr<strong>in</strong>t had exp<strong>and</strong>edto <strong>in</strong>clude Tr<strong>in</strong>idad <strong>and</strong> Tobago <strong>and</strong> the Dom<strong>in</strong>ican Republic reported <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> 85% <strong>and</strong>68% <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s.10

Executive SummaryThe peak <strong>of</strong> HotSpot activity occurred <strong>in</strong> early October with a massive area <strong>of</strong> warm water cover<strong>in</strong>gvirtually all the central <strong>and</strong> eastern <strong>Caribbean</strong>. A series <strong>of</strong> Hurricanes had helped cool the waters<strong>of</strong> the Northern <strong>Caribbean</strong>; but there were no <strong>hurricanes</strong> to pass through the Lesser Antilles wherethe waters were warmest. In mid to late October the HotSpot ‘followed the sun’ southward <strong>and</strong> thenbathed the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s Antilles <strong>and</strong> the northern coast <strong>of</strong> South America. By early November, theHotSpot had virtually dissipated <strong>and</strong> conditions had returned to normal. However, this 4 monthperiod <strong>of</strong> unusually warm waters had wreaked havoc throughout the Wider <strong>Caribbean</strong> as is described<strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g chapters.By October, dangerously elevated sea temperatures had been bath<strong>in</strong>g the Lesser Antilles foralmost 6 months; most <strong>of</strong> this time the temperatures exceeded the normal <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>thresholds. This susta<strong>in</strong>ed thermal stress resulted <strong>in</strong> the most severe <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong>mortality ever recorded <strong>in</strong> the Lesser Antilles with 25% to 52% <strong>coral</strong> mortality <strong>in</strong> the FrenchWest Indies, <strong>and</strong> the most severe <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> event ever recorded around Barbados. Bleach<strong>in</strong>gaffected all <strong>coral</strong> species at all depths. In the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s Antilles there was 80% <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>around the isl<strong>and</strong>s to the north, near the British Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s, whereas around Bonaire <strong>and</strong>Curacao <strong>in</strong> the south there was only m<strong>in</strong>or <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> virtually no mortality. Further to theeast there was 66 to 80% <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>coral</strong> cover on Tobago. On average, the accumulated<strong>Caribbean</strong> thermal stress dur<strong>in</strong>g the August-November period was greater than had beenexperienced by these <strong>reefs</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the previous 20 years comb<strong>in</strong>ed.A second bout <strong>of</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> started when the HotSpot ‘followed the sun’ with Colombia seriouslyaffected <strong>in</strong> October <strong>and</strong> the peak <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Venezuela <strong>in</strong> November <strong>and</strong> December <strong>2005</strong>.Bleach<strong>in</strong>g was highly variable with sites report<strong>in</strong>g anyth<strong>in</strong>g from zero to 100% <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, butthe mean was closer to 25%; fortunately mortality on <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>in</strong> tropical South America was farless than on <strong>reefs</strong> to the north.11

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>Wh y Cl i mat e Ch a n g e is a Th r e at to Co r a l ReefsCorals bleach when the <strong>coral</strong> animal host is stressed <strong>and</strong> expels the symbiotic zooxanthellae(algae) that provide much <strong>of</strong> the energy for <strong>coral</strong> growth, <strong>and</strong> <strong>coral</strong> reef growth. Althoughseveral different stresses cause <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, by far the most significant cause <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> the past 25 years has been sea surface temperatures that exceed the normal summer maximaby 1 or 2 o C for at least 4 weeks. This results <strong>in</strong> excessive production <strong>of</strong> toxic compounds <strong>in</strong> thealgae that are transferred to the host <strong>coral</strong>. The host <strong>coral</strong> reacts by expell<strong>in</strong>g their symbioticalgae, leav<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>coral</strong> ghostly white <strong>and</strong> particularly susceptible to death from starvationor disease. If conditions become more favorable, <strong>coral</strong>s <strong>of</strong>ten recover, although they <strong>of</strong>tenexperience reduced growth <strong>and</strong> may skip reproduction for a season. In <strong>2005</strong>, many bleached<strong>coral</strong>s did eventually die.Coral <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> was first noticed as a significant problem <strong>in</strong> the wider <strong>Caribbean</strong> region <strong>in</strong> 1983.Concurrently there were <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> <strong>coral</strong> disease across the region, thus the assumption wasmade that these were both associated with higher temperatures. The <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> outbreaks<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fectious diseases, such as white plague, have caused such major losses <strong>in</strong> the branch<strong>in</strong>gstaghorn <strong>and</strong> elkhorn <strong>coral</strong>s (Acropora cervicornis <strong>and</strong> A. palmata), that they were added tothe List <strong>of</strong> Endangered <strong>and</strong> Threatened Wildlife under the Endangered Species Act <strong>of</strong> U.S.A. <strong>in</strong>April 2007. The list<strong>in</strong>g as Threatened Species requires that US government agencies maximizetheir efforts at conserv<strong>in</strong>g these species, which are the most characteristic <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>reefs</strong><strong>and</strong> were once major contributors to reef construction.The <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong> ‘co<strong>in</strong>cided’ with major outbreaks <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> diseases which saw extensiveshr<strong>in</strong>kage <strong>in</strong> the cover <strong>of</strong> live <strong>coral</strong>s throughout the <strong>Caribbean</strong>. While many <strong>coral</strong>s started torecover when seawater temperatures dropped with the onset <strong>of</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter, <strong>coral</strong> diseases broke out<strong>and</strong> resulted <strong>in</strong> significant losses <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> cover, notably along the coast <strong>of</strong> Florida (Chapter 6),<strong>in</strong> Belize (Chapter 5), the Virg<strong>in</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>s (Chapter 7), <strong>and</strong> the Lesser Antilles (Chapter 8). Theaccepted explanation is that bleached <strong>coral</strong>s are stressed, lack reserve lipid supplies <strong>and</strong> areeffectively starv<strong>in</strong>g, mak<strong>in</strong>g them more susceptible to disease.Ocean acidification is a parallel climate change threat to <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> that results from <strong>in</strong>creasedconcentrations <strong>of</strong> CO 2dissolv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> seawater, which reduces its pH. This process is called ‘oceanacidification’, <strong>and</strong> by the end <strong>of</strong> this century, acidification may be proceed<strong>in</strong>g at a rate that is100 times faster <strong>and</strong> with a magnitude that is 3 times greater than anyth<strong>in</strong>g experienced onthe planet <strong>in</strong> the last 21 million years. How this will affect mar<strong>in</strong>e ecosystems is unknown, butimpacts on mar<strong>in</strong>e calcifiers could be considerable. Us<strong>in</strong>g the pH levels expected by the end <strong>of</strong>this century, laboratory studies show a significant reduction <strong>in</strong> the ability <strong>of</strong> reef-build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong>sto grown their carbonate skeletons, mak<strong>in</strong>g them both slower to grow <strong>and</strong> more vulnerableto erosion. This would also affect the basal structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> reef itself. While the long termconsequences <strong>of</strong> ocean acidification on <strong>coral</strong>s is not known, <strong>coral</strong>s do not seem to be able toeasily adapt to such rapid changes. All predictions from climate change models po<strong>in</strong>t to oceanacidification hav<strong>in</strong>g progressively more negative impacts on <strong>coral</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>.Hurricanes <strong>and</strong> extreme weather events are also predicted to become more frequent <strong>and</strong> severeas the pace <strong>of</strong> climate change quickens. There is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g evidence that the proportion <strong>of</strong>more destructive <strong>hurricanes</strong> has <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> recent decades, although the total <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong>tropical storms has not <strong>in</strong>creased. Stronger <strong>hurricanes</strong> will result <strong>in</strong> more severe wave damage12

Executive Summary<strong>and</strong> flood<strong>in</strong>g from the l<strong>and</strong>, thereby add<strong>in</strong>g an additional stress to already stressed <strong>reefs</strong>. Lowto moderate strength <strong>hurricanes</strong> can be beneficial dur<strong>in</strong>g summer, however, by cool<strong>in</strong>g surfacewaters <strong>and</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g the likelihood <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.There is <strong>in</strong>sufficient evidence or <strong>in</strong>dications that the other potential climate change stresseswill result <strong>in</strong> significant damage to <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>. There is a potential for negative impacts frompossible shift<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> ocean currents or rises <strong>in</strong> UV concentrations; however these are not evidentat the moment. Sea level rise will not directly threaten <strong>coral</strong>s, but may render <strong>coral</strong> reef isl<strong>and</strong>sun<strong>in</strong>habitable, thereby threaten<strong>in</strong>g <strong>coral</strong> isl<strong>and</strong> cultures <strong>and</strong> nations.Implications o f <strong>2005</strong> f o r Co r a l Ma n a g e r sCoral reef managers were unprepared for the climate-related destructive events <strong>of</strong> 1998. Many<strong>coral</strong> reef managers <strong>in</strong> the Indian Ocean <strong>and</strong> Western Pacific reported that massive <strong>coral</strong><strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> mid to late 1998 was devastat<strong>in</strong>g their <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>, <strong>and</strong> they asked ‘what have I donewrong to cause the <strong>coral</strong>s to die’. They were perplexed that <strong>coral</strong>s were dy<strong>in</strong>g on the same <strong>reefs</strong>that they were actively manag<strong>in</strong>g to remove pollution, sedimentation <strong>and</strong> over-fish<strong>in</strong>g stresses.The cause <strong>of</strong> the problems to their <strong>reefs</strong> was related to climate change via a particularly severeEl Niño <strong>and</strong> La Niña climate switch that raised sea surface temperatures (SSTs) above levelsthat had ever been recorded on those <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>. We now know that no management actionscould have prevented the extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong> death; the only advice the <strong>coral</strong> reef research <strong>and</strong>management community could <strong>of</strong>fer was that ‘better managed <strong>reefs</strong> will recover more rapidlythan those under human stresses’.The events <strong>of</strong> 1998 stimulated the <strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>coral</strong> reef community to develop advice for<strong>coral</strong> reef managers faced with similar circumstances <strong>in</strong> the future. A Reef Manager’s Guideto Coral Bleach<strong>in</strong>g was developed <strong>in</strong> 2006 to provide that advice for <strong>coral</strong> reef managers facedwith stresses beyond their immediate control. The report is summarized by the authors <strong>in</strong>Chapter 10 <strong>and</strong> provides reef managers with the explanations why <strong>reefs</strong> are damaged by suchclimate related events <strong>and</strong> expla<strong>in</strong>s why some <strong>reefs</strong> resist <strong>coral</strong> <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> others are moreresilient i.e. they recover faster <strong>after</strong> severe losses.The report guides reef managers <strong>in</strong>to steps they can take at national <strong>and</strong> global levels to raiseawareness <strong>of</strong> the potential devastation that <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g global climate change, though the release<strong>of</strong> greenhouse gases, can have on <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>. However, the emphasis is on provid<strong>in</strong>g managerswith practical advice on how to <strong>in</strong>crease protection <strong>of</strong> those <strong>reefs</strong> that are either naturallyresistant or tolerant to <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, assist <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g adaptation mechanisms that enhance reefresilience, while simultaneously reduc<strong>in</strong>g local pressures on the <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>and</strong> nearby ecosystemsto enhance chances for natural recovery. Importantly, the Guide advises reef managers on howto engage with local people <strong>and</strong> assist <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g socioeconomic well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>gthem on board to assist <strong>in</strong> the susta<strong>in</strong>able use <strong>of</strong> their <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>.An d t h e Fu t u r eSadly for <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>, all predictions from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(IPCC) reports <strong>in</strong> 2007 <strong>in</strong>dicate that the extreme warm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>2005</strong> will not be an isolated event(Chapter 11). It will probably happen aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the future <strong>and</strong>, when it does, the impacts willbe even more severe. The IPCC concluded that human-<strong>in</strong>duced climate change will warm the13

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> Coral Reefs <strong>after</strong> Bleach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Hurricanes <strong>in</strong> <strong>2005</strong>world by 1.8 to 4.0ºC by the year 2100. This warm<strong>in</strong>g will affect most <strong>of</strong> the wider <strong>Caribbean</strong>Sea mak<strong>in</strong>g years like <strong>2005</strong> more common <strong>and</strong> more devastat<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>.In addition, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g acidity <strong>in</strong> the seawater with the solution <strong>of</strong> more CO 2 will result <strong>in</strong>slower growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s that are try<strong>in</strong>g to recover from <strong>bleach<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> other disturbances.One other potential consequence <strong>of</strong> the human-<strong>in</strong>duced warm<strong>in</strong>g is an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the frequency<strong>of</strong> more damag<strong>in</strong>g Category 4 <strong>and</strong> 5 <strong>hurricanes</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Caribbean</strong>. These storms develop aswaters warm over the tropical North Atlantic <strong>and</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> waters. It is predicted that warmersurface waters with <strong>in</strong>creased amounts <strong>of</strong> thermal energy will fuel <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> tropical stormstrength. The latest predictions are for an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the more <strong>in</strong>tense Category 4 <strong>and</strong> 5<strong>hurricanes</strong> that will probably cause significant damage to the <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong> <strong>and</strong> the communitiesthat depend upon them (Chapter 3).50% Hurricanes per category40302010Category 1Category 2 & 3Category 4 & 5070-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 90-94 95-99 00-04 05-09 10-14 14-195 – year periodThis figure shows the proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tense <strong>hurricanes</strong> has been <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>ce 1970 while thetotal number <strong>of</strong> <strong>hurricanes</strong> has not changed much. These graphs plot all global <strong>hurricanes</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>in</strong>to 5 year periods from 1970 to 2004, with projected trends added to 2019. Category 1 storms arerelatively weak whereas Category 5 storms are particularly devastat<strong>in</strong>g (adapted from Webster <strong>2005</strong>).Dashed l<strong>in</strong>es show significant l<strong>in</strong>ear trends.This is a pivotal moment for the <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>. The world is already committed to some furtherwarm<strong>in</strong>g due to past greenhouse gas emissions <strong>and</strong> the expected emissions from exist<strong>in</strong>g worldenergy <strong>in</strong>frastructure (Chapter 2). Thanks to more than a century <strong>of</strong> ‘committed warm<strong>in</strong>g’;events like <strong>2005</strong> are expected to occur more frequently by the 2030s. The only possible way tosusta<strong>in</strong> some live <strong>coral</strong> on the <strong>reefs</strong> around the world will be to carefully manage the directpressures like pollution, fish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> damag<strong>in</strong>g coastal developments, <strong>and</strong> hope that some<strong>coral</strong> species are able to adapt to the warmer environment. However, a dramatic reduction <strong>in</strong>greenhouse gas emissions <strong>in</strong> the next 20 years will be critical to control further warm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>higher CO 2levels that will probably reduce the robustness <strong>and</strong> competitive fitness <strong>of</strong> <strong>coral</strong>s <strong>and</strong>limit the habitats for many other organisms liv<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>coral</strong> <strong>reefs</strong>.14