Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2009 â In Brief

Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2009 â In Brief

Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2009 â In Brief

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

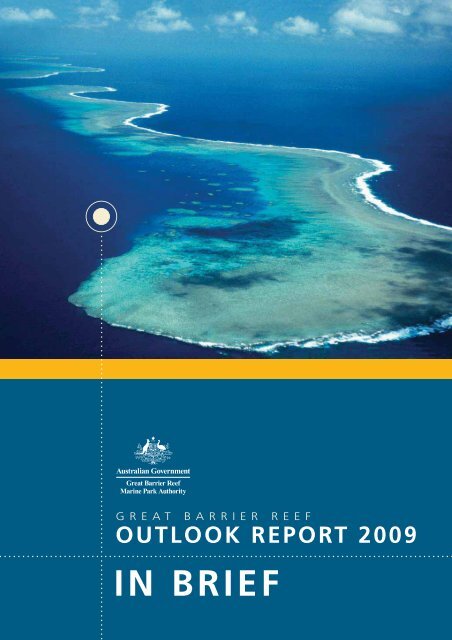

GREAT BARRIER REEFOUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong>IN BRIEF

GREAT BARRIER REEFOUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong>IN BRIEF

© Commonwealth of AustraliaPublished by the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Authority July <strong>2009</strong>ISBN: 978 1 876945 91 6 (pbk.)ISBN: 978 1 876945 92 3 (CD-ROM)This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproducedby any process without the prior written permission of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Authority. Requests andinquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to General Manager, Communication and PolicyCoordination, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Authority, PO Box 1379, Townsville Qld 4810.National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Authority.<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> outlook report <strong>2009</strong> : in brief / <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Authority.ISBN: 978 1 876945 91 6 (pbk.)Marine resources--Queensland--<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.Conservation of natural resources--Queensland--<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.Marine parks and reserves--Queensland--<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>--Management.Environmental management--Queensland--<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> (Qld.)551.42409943Design and layout: Tristan James Design Services.Figures: Extremely Graphic.Printed on a waterless press using environmentally responsible print techniquesand sustainable paper stocks.Further information is available from:<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Authority2-68 Flinders Street East (PO Box 1379)Townsville Queensland 4810Telephone +617 4750 0700Fax +617 4772 6093Web site www.gbrmpa.gov.au

PREFACEThe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is a World Heritage Area that is greatly valued by Australians and by people throughoutthe world. It is the largest coral reef ecosystem on the planet and supports an outstanding array of plantsand animals. Most commercial and non-commercial use of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is dependent on an intact,healthy and resilient ecosystem and it continues to be a significant economic resource for Australia and localcommunities.The significance of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> makes it especially important that we regularly collate ourknowledge of the ecosystem and take stock of its future. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2009</strong>assesses what is known about the ecosystem, its use, its management and the pressures it is facing, andis a window into its future. It identifies climate change, continued declining water quality from catchmentrunoff, loss of coastal habitats from coastal development and a small number of impacts from fishing as thepriority issues reducing the resilience of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. It also highlights gaps in information requiredfor a better understanding of ecosystem resilience.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2009</strong> was prepared by the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Authoritybased on the best available information. Many people with an interest in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> contributedto its development, including leading scientists, industry representatives and the community. The <strong>Report</strong> wasindependently peer reviewed.The <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> was provided to the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts on 30 June<strong>2009</strong> and subsequently tabled in the Australian Parliament.This <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2009</strong> – <strong>In</strong> <strong>Brief</strong> presents the key findings of the full <strong>Report</strong> supportedby a selection of the evidence used. Its structure mirrors the <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> itself, with a chapter for each ofthe eight assessments required under Section 54 of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Act 1975, includingextracts from the assessment summaries.The full text of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2009</strong> is available online at www.gbrmpa.gov.au or onthe CD at the back of this publication.Russell ReicheltChairman and Chief Executive Officer<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park AuthorityPREFACE

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THEGREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong>The following is the complete text of the Executive Summary of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2009</strong>.The outlook for the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem is at a crossroad, and it is decisions made in the next few yearsthat are likely to determine its long-term future. Unavoidably, future predictions of climate change dominatemost aspects of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>’s outlook over the next few decades. The extent and persistence of thedamage to the ecosystem will depend to a large degree on the amount of change in the world’s climate andon the resilience of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem in the immediate future.This first <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> identifies climate change, continued declining water quality from catchment runoff,loss of coastal habitats from coastal development and remaining impacts from fishing and illegal fishing andpoaching as the priority issues reducing the resilience of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. It also highlights gaps ininformation required for a better understanding of ecosystem resilience.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is one of the most diverse and remarkable ecosystems in the world and remains one ofthe most healthy coral reef ecosystems. Nevertheless, its condition has declined significantly since Europeansettlement and, as a result, the overall resilience of the ecosystem has been reduced.While populations of almost all marine species are intact and there are no records of extinctions, someecologically important species, such as dugongs, marine turtles, seabirds, black teatfish and some sharks, havedeclined significantly. Although the declines of loggerhead turtles and dugongs are believed to have halted,there are few examples of increasing populations in species of conservation concern. The obvious example isthe humpback whale, which is recovering strongly after being decimated by whaling. Disease in corals andpest outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish and cyanobacteria appear to be becoming more frequent and moreserious.Coral reef habitats fluctuate naturally depending on changes in environmental conditions, but they are graduallydeclining, especially inshore as a result of poor water quality and the compounding effects of climate change.Habitats more remote from human use, such as the continental slope and reefs in the far north are believedto be in very good condition and portions of the lagoon floor are recovering from previous effects of trawling.Most commercial and non-commercial use of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is dependent on an intact, healthy andresilient ecosystem and it continues to be a significant economic resource for regional communities andAustralia. Millions of people continue to enjoy their visits to the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. Major changes to thecondition of the ecosystem will have social and economic implications.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park is considered by many to be a leading example of world’s best practicemanagement. However, the effectiveness of management is challenged because complex factors that havetheir origin beyond the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region, namely climate change, catchment runoff and coastaldevelopment cause some of the highest risks to the ecosystem. These factors are playing an increasing role indetermining the condition and future of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.Almost all the biodiversity of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> will be affected by climate change, with coral reef habitatsthe most vulnerable. Coral bleaching resulting from increasing sea temperature and lower rates of calcificationin skeleton-building organisms, such as corals, because of ocean acidification, are the effects of most concernand are already evident.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> continues to be exposed to increased levels of sediments, nutrients and pesticides, whichare having significant effects inshore close to developed coasts, such as causing die-backs of mangroves andincreasing algae on coral reefs. Substantial resources are being provided to improve water quality to the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, but progress is slow and patchy.Coastal development is increasing the loss of coastal habitats that support the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. Humanpopulation increases within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> catchment are projected to be nearly two per cent perEXECUTIVE SUMMARYi

annum. This will place greater pressure on the ecosystem and increase use of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region.<strong>In</strong>tegrated planning, knowledge and compliance in managing coastal development are areas highlighted asrequiring improvement.While significant improvements have been made in reducing the impacts of fishing in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>,such as bycatch reduction devices, effort controls and closures, important risks to the ecosystem remain fromthe targeting of predators, the death of incidentally caught species of conservation concern, illegal fishingand poaching. The flow on ecosystem effects of losing predators, such as sharks and coral trout, as wellfurther reducing populations of herbivores, such as the threatened dugong, are largely unknown but have thepotential to alter food web interrelationships and reduce resilience across the ecosystem.Non-extractive uses within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, such as commercial marine tourism, shipping and defenceactivities, are independently assessed as more effectively managed and are a lower risk to the ecosystem;however the risk of introduced species is likely to increase with projected increases in shipping when globaleconomic recovery occurs. While many of the management measures employed in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Region and beyond are making a positive difference, for example the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park ZoningPlan 2003, the ability to address cumulative impacts is weak.Given the strong management of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, it is likely that the ecosystem will survive betterunder the pressure of accumulating risks than most reef ecosystems around the world. However, even withthe recent management initiatives to improve resilience, the overall outlook for the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is poorand catastrophic damage to the ecosystem may not be averted. Ultimately, if changes in the world’s climatebecome too severe, no management actions will be able to climate-proof the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem.Further building the resilience of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> by improving water quality, reducing the loss of coastalhabitats and increasing knowledge about fishing and its effects, will give it the best chance of adapting to andrecovering from the serious threats ahead, especially from climate change.iiGREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong> IN BRIEF

TABLE OF CONTENTSExecutive Summary of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2009</strong> ..................................................iAbout the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> ...................................................................................iv1. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ....................................................................................................................12. Biodiversity ....................................................................................................................................33. Ecosystem Health ...........................................................................................................................54. Commercial and Non-Commercial Use ..........................................................................................75. Factors <strong>In</strong>fluencing the <strong>Reef</strong>’s Values ............................................................................................96. Existing Protection and Management ..........................................................................................137. Ecosystem Resilience ....................................................................................................................158. Risks to the <strong>Reef</strong> ...........................................................................................................................179. Long-Term <strong>Outlook</strong> .......................................................................................................................19Appendix 1 - Developing the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> ....................................................22Map 1 The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region ...........................................................................................................................2List of FiguresFigure 2.1 Hard coral cover in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 1986-2008, as measured using manta tow surveys ...................3Figure 2.2 <strong>Reef</strong> shark and coral trout densities across zones ........................................................................................4Figure 2.3 Dugong populations in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> .............................................................................................4Figure 3.1 Modelled exposure to sediments and dissolved inorganic nitrogen, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2008 .....................5Figure 3.2 Changes in calcification in Porites spp., <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 1900-2005 .......................................................6Figure 3.3 Crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) outbreaks across zones, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 1994-2004 ............................6Figure 4.1 Distribution of tourism activity across the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2008 .............................................................7Figure 4.2 Retained and non-retained fisheries catch, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2007 ...........................................................7Figure 4.3 Shipping activity in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 1997-2008 ................................................................................8Figure 4.4 Main activities of visitors to the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ......................................................................................8Figure 5.1 Predicted changes in conditions suitable for calcification ............................................................................9Figure 5.2 Projected vulnerabilities of components of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem to climate change ...............10Figure 5.3 Loss of habitats that support the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ..................................................................................11Figure 5.4 Population growth and predictions in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> catchment ...................................................11Figure 5.5 Sediment loads entering the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2005/06 wet season ........................................................11Figure 5.6 Nutrient loads entering the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2005 dry season and 2005/06 wet season ........................12Figure 5.7 The effect of declining water quality on the ecosystem .............................................................................12Figure 6.1 The management cycle ..............................................................................................................................13Figure 7.1 Resilience of a coral reef habitat ................................................................................................................15Figure 7.2 Recovery of coral following various disturbances ......................................................................................16Figure 7.3 Recovery of the eastern Australian humpback whale population since whaling ceased in the 1960s ........16Figure 8.1 Level of risk, extent and timing of threats and their driving factors ...........................................................17Figure 8.2 Effectiveness of existing management for identified risk factors ...............................................................18CONTENTSiii

ABOUT THEGREAT BARRIER REEFOUTLOOK REPORT<strong>In</strong> 2006, the Australian Government resolved thatdecision making for long-term protection of the<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> should be underpinned by aperiodic <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong>. The <strong>Report</strong> would be aregular and reliable means of assessing performancein an accountable and transparent manner and a keyinput for any future changes to zoning plans and theconsideration of broader issues by government.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Act 1975 wasamended in 2007 requiring the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Marine Park Authority to prepare an <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong>for the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region every five years.The Act stipulates that the <strong>Report</strong> must be given tothe Minister for the Environment, Heritage and theArts for tabling in both houses of the AustralianParliament. The Act does not provide for the <strong>Outlook</strong><strong>Report</strong> to make recommendations about futureprotection or management initiatives.The first <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> has beenprepared by the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine ParkAuthority and is available online at www.gbrmpa.gov.au.The area examined in the <strong>Report</strong> is the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> Region as defined in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Marine Park Act 1975. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Regioncovers the area of ocean from the tip of Cape Yorkin the north to past Lady Elliot Island in the south,with mean low water as its western boundary andextending eastwards a distance of between 70 and250km (see Map 1).A number of Australian and Queensland Governmentagencies, researchers, industry representatives andmembers of the public contributed to developmentof the <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong>. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> MarinePark Authority’s four <strong>Reef</strong> Advisory Committees(external experts who provide independent adviceon critical issues) and 11 Local Marine AdvisoryCommittees (committees centred on regionalcentres along the coast) provided advice throughoutthe <strong>Report</strong>’s development. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Marine Park Authority held community workshopsto learn about changes to the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>by listening to community members’ stories of thepast. <strong>In</strong> addition, an <strong>Outlook</strong> Forum attended by 42participants including scientists, leaders from industry,interest groups and the community and governmentrepresentatives developed likely ‘outlooks’ for the<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.Two experts in protected area management,monitoring and evaluation, public policy andgovernance were commissioned to undertake anindependent assessment of existing protection andmanagement. Their report forms the basis of theassessment of existing measures to protect andmanage the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem.All of the habitats and species of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Region are considered in the <strong>Report</strong>, including species ofconservation concern such as the hawksbill turtle.Throughout development of the <strong>Report</strong>, an<strong>Outlook</strong> Reference Group comprising eightexperts in environmental reporting, protected areamanagement and communication provided adviceand guidance on information available, assessmentmethods and community engagement andpresentation.Finally, four reviewers appointed by the Ministerfor the Environment, Heritage and the Artsindependently reviewed the contents of the <strong>Outlook</strong><strong>Report</strong>. These reviewers are recognised national andinternational experts with biophysical and/or socioeconomicexpertise and achievements, includingconducting high level policy and scientific reviews.Their comments were considered and incorporatedwhere appropriate in finalising the <strong>Report</strong>.ivGREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong> IN BRIEF

The <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> assesses the current state ofthe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem’s environmental,social and economic values, examines the pressuresand current responses and finally considers the likelyoutlook. It is structured around the eight assessmentsrequired by the Act, with each assessment forming achapter of the <strong>Report</strong>.For each of the assessments required under the Act,a set of Assessment Criteria allow an ordered analysisof the available evidence. An overall grade for eachAssessment Criterion is provided, based on a series ofgrading statements.This approach has been developed specifically forthe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> to meet thelegislative requirements. It is intended that future<strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong>s will follow the same process so thatchanges and trends can be tracked over time.The information featured in the <strong>Report</strong> is only a smallportion of all that is known about the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> Region. No new research was undertaken as partof developing the <strong>Report</strong>; rather, the evidence usedis derived from existing research and informationsources. The complete set of evidence used todevelop the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> isavailable online at www.gbrmpa.gov.au.Required assessmentin accordance with the<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Marine Park Act 1975Evidencesummarised in the <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong>,complete set available online atwww.gbrmpa.gov.auAssessment Criteriafor each required assessmentGrading Statementsfor each of theAssessment CriteriaConsideration of evidencefor each of theAssessment CriteriaGrade and AssessmentSummaryfor each of theAssessment CriteriaThe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>2009</strong> isstructured around the eight assessments required underSection 54 of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park Act1975.Overall Summaryfor each required assessmentThe <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> is based on the best availableevidence. A set of grading statements (available in thefull <strong>Report</strong>) guide the allocation of a grade for eachAssessment Criterion in each of the required assessments.ABOUT THE GREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORTv

1THE GREATBARRIER REEFThe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is a national and international icon,famous for its beauty and vast scale. It is the largest andbest known coral reef ecosystem in the world, spanning alength of 2300 km along two-thirds of the east coast ofQueensland. The reefs of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> - almost3000 in total - represent about 10 per cent of all the coralreef areas in the world. Virtually all groups of marine plantsand animals are abundantly represented in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong>, with thousands of different species living there.Areas of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region have been progressivelyincluded in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park since the late1970s. Today almost all of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystemis included within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park whichextends over approximately 344 400 km 2 (see Map 1). ThisCommonwealth Marine Park is complemented by the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Coast Marine Park in adjacent Queenslandwaters.traditional use. It brings billions of dollars into Australia’seconomy each year, and supports more than 50 000 jobs.Within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park, a number ofactivities are strictly prohibited (such as mining and oildrilling) and there is careful management of all other activities(such as fishing, commercial marine tourism and shippingoperations). A range of measures are employed to managethe various uses of the Marine Park and to protect its values.For example, a Zoning Plan defines what activities can occurin which locations, both to protect the marine environmentand to separate potentially conflicting activities.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is a national and international icon. Itwas part of the Torch Relay for the 2000 Olympic Games held inSydney, Australia. (Photo courtesy of the Quicksilver Group)The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> from spaceThe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> hugs the east coast of Queensland,Australia. Its variety of reefs is substantially greater than in anyother place on Earth. (Photo courtesy of the European SpaceAgency)The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park is a multiple use marinepark, supporting a wide range of uses, including commercialmarine tourism, defence activities, fishing, ports andshipping, recreation, scientific research and <strong>In</strong>digenousAbout 70 <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander Traditional Owner clan groups hold a range ofpast and present heritage values for their land and seacountry, and for surrounding sea countries. These valuesmay be cultural, spiritual, economic, social or physical, anddemonstrate continuing connections with the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> Region and its natural resources.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> was inscribed on the World HeritageList in 1981, the first coral reef ecosystem in the world tohave this distinction and the only such coral reef region thathas ever qualified on all four natural criteria. This recognitioncontinues to highlight the international significance ofthe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>; it also carries an obligation andresponsibility to protect and conserve its values for all futuregenerations and to present its values to the world.<strong>In</strong> May 2007, existing Australian World Heritage properties(such as the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>) were transferred onto theNational Heritage List for their World Heritage values. <strong>In</strong>addition, five Commonwealth Heritage places within the<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region and many places of historicalsignificance including lighthouses and shipwrecks aremanaged to protect heritage values.1GREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong> IN BRIEF

PAPUANEW GUINEATalbot IslandsTorres10°SBadu IslandThursdayIslandEndeavourStraitBamagaMoaIslandCAPESaibaiIslandStrait<strong>Reef</strong>sWarriorNewcastle BayOrford BayDaruShelburne Bay145 E 150 EIslandsGULF OF PAPUADykeAcklandBayGoodenough<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> RegionIslandAnchor CayCollingwoodFergusson IslandWoodlarkLagoon <strong>Reef</strong>BayPort MoresbyIslandMurray IslandsRaine Island<strong>Great</strong> Detached<strong>Reef</strong>200Portlock <strong>Reef</strong>sBoot <strong>Reef</strong>Ashmore <strong>Reef</strong>20010°40’55"S145°00’04"EEastern Fields2000FAR NORTHERNMANAGEMENT AREAO W E NS T A N L E YR A N G E200GoodenoughBayGREAT BARRIER REEF REGION AND WORLD HERITAGENormanby IslandAREA BoundaryGREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK BoundaryLouisiade ArchipelagoMisima IslandGREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK MANAGEMENTAREA BoundaryGREAT BARRIER REEF PROVINCE Tagula Island BoundaryGREAT BARRIER REEF CATCHMENT BoundaryRosselIsland10°SWenlockTemple BayRiverWeipaYORKAurukun RiverArcherLockhartRiverLloyd BayG RE AT12°59’55"S145°00’04"E4000CORAL SEA15°S20°S25°STropic of Capricorn(23°26’30”S)CoenPENINSULAPormpuraawKowanyamaNormanClaraGilbertHolroydColemanStaatenRiverMitchellRiverRiverRiverRiverRiverEinasleighGRiverPalmerStawellLyndPrincessCharlotteBayRiverRiverNormanbyRiverFLINDERS GROUPHope ValeCooktownRiverRiverNinian BayStarcke RiverDaintree RiverMossmanPort DouglasCairnsGordonvaleLake TinarooNorth Johnstone RiverSouth Johnstone RiverN0 100200 300KilometresMap No. SDC 090213 1 February <strong>2009</strong>RQUEENSLANDEATHerbertAliceLizard IslandLow IslandsTrinityBayBabindaGreen IslandFitzroy Island<strong>In</strong>nisfailTullyDunk (Coonanglebah)IslandRockingham BayCardwellCapeTully RiverLakeBuchananLake GalileeBarcooRiverHinchinbrookIslandOsprey <strong>Reef</strong>Shark <strong>Reef</strong>Bougainville <strong>Reef</strong>PALM<strong>In</strong>gham ISLANDSHalifax BayMagnetic IslandGreenBayTownsville BowlingDRiverBurdekinRiver2000RiverBelyando20014°59’55"S146°00’04"EIV I D IN GCAIRNS / COOKTOWNMANAGEMENT AREARiverRiver200Ross RiverDamLakeDalrymple17°29’55"S147°00’04"EAyrBowenNogoa RiverFlora <strong>Reef</strong>145°E 150°EWILLIS GROUPMap 1 The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> RegionThe <strong>Outlook</strong> <strong>Report</strong> is a report about the entire <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region, plus adjacent ecosystems where relevant.Holmes <strong>Reef</strong>Dart<strong>Reef</strong>B A R R I ERiverLake MaraboonUpstart BayAirlie BeachProserpineMoore <strong>Reef</strong>sHerald CaysGloucesterIslandBowenMaranoaBrokenIsaacRiverRiver200RRiverDianne BankHeralds SurpriseCometFlinders <strong>Reef</strong>sMackayPioneerMacKenzieRiverMagdelaine CaysCUMBERLANDRiverSarinaDawsonMalay <strong>Reef</strong>Abington <strong>Reef</strong>WhitsundayGroupLindeman GroupRiverLake Nuga NugaRA200ISLANDSCORINGA ISLANDSNORTHUMBERLANDCreekTooloombahBroad SoundRockhamptonRiver200Fitzroy RiverDawson200RiverPercy IslesISLANDSDiamondIsletsTregrosse <strong>Reef</strong>sTOWNSVILLE / WHITSUNDAYMANAGEMENT AREAN GEBayShoalwaterTownshend IslandYeppoonGladstoneKeppelIslandsKeppel BayCalliope RiverLake CaniaLake WurumaCurtisIslandBoyne RiverLake MonduranLakeBoondoomaBurnett200REEFPaget CaySwain<strong>Reef</strong>sTurtle IsletLihou <strong>Reef</strong>Capricorn ChannelMarion <strong>Reef</strong>CAPRICORN GROUPCurtis ChannelKolan RiverBundabergRiverLakeBarambah200BUNKER GROUPHervey BayMaryboroughGympieNambourSOUTHPACIFICMary2000OCEANMACKAY/CAPRICORNMANAGEMENT AREALady Elliot IslandHerveyBayRiver200SomersetLake20°59’55"S152°55’04"EFraser IslandWideBay200CaloundraSaumarez <strong>Reef</strong>South West Cay2000200400040002000200015°S20°SFrederick<strong>Reef</strong>s24°29’55"S154°00’04"E400025°STHE GREAT BARRIER REEF2

2BIODIVERSITYBiodiversity is the variety among all plants and animals. Itencompasses all living things, from microbes and singlecell algae to marine turtles and whales, and their habitats.Importantly, it is not just a measure of how many speciesthere are. Rather, it encompasses all natural variation - fromgenetic differences within one species to variations across ahabitat or a whole ecosystem.The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region is vast, covering 14 degreesof latitude and extending 70 to 250km from the coast. It isone of the world’s best known and most complex naturalsystems and continues to support extensive plant and animalbiodiversity. Coral reefs are the best known part of the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region, yet they make up only seven per cent ofits area. Over one-third of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region is infact continental slope and extremely deep oceanic habitatsThe sheer scale of the ecosystem means monitoring hasfocused on a few key habitats and species or groups of species,generally those that are iconic (such as coral reefs, seabirds),commercially important (such as seagrass meadows, coraltrout) or threatened (such as dugongs, marine turtles). Thereare few long-term monitoring programs established and thebaseline from which to make comparisons is different foreach group studied.types within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> (for example the lagoonfloor, shoals, Halimeda banks and the continental slope).The overall area of mangrove forest adjacent to the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> appears to be generally stable except wherethere is significant coastal development. Changes in seagrasscommunities appear to be mainly due to natural cyclesof decline and recovery although they are influenced byrunoff from catchments. Available evidence indicates thatthe overall status of coral reefs on the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> isrelatively good. There is some evidence of a small decline incoral reef habitat over recent decades (figure 2.1), more soin inshore areas, but the trends are difficult to interpret ascoral reefs are naturally very dynamic habitats. The declinemay have already begun to affect species that depend oncoral reef habitat.% cover40353025201510501986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007Figure 2.1Hard coral cover in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>,1986-2008, as measured using manta towsurveys 1Assessments of coral reef status are usually based on the amount ofcoral on a reef. On the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, coral cover has undergonea wide range of changes and there is no strong, consistent overalltrend. As measured using manta tow surveys throughout the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, average coral cover has declined over the last 22years, amounting to an average annual change of -0.29%. Resultsof another survey technique from 1993 to 2007 show a very slightincrease. Other analyses suggest there may have been significantdeclines in coral cover prior to the implementation of systematiclong-term monitoring.Ribbon reefs form an almost continuous chain in the far northern<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.Habitats to support species The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>supports a wide variety of habitats from mangrovesand beaches to deep open water. There is little detailedinformation about the status and trends of many habitatPopulations of species and groups of species The<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem is made up of thousands ofspecies. Nowhere near all of them have been identifiedand described. Populations appear to be intact for the vastmajority of species or groups of species in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem. Latitudinal and cross-shelf biodiversityappears to be being maintained; however inshore speciesand their habitats adjacent to the developed coast are undermore pressure than those both offshore and further north.Little is known about the status of most <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>species such as non-commercial invertebrates, planktonand microbes. Of the more than 1600 bony fish species,3GREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong> IN BRIEF

only a few are known to have locally depleted populations.Populations of a number of ecologically significant species,particularly predators (such as sharks, and seabirds) and largeherbivores (dugongs), are known to have seriously declined(figures 2.2 and 2.3). Declines in species or groups of specieshave been caused by a range of factors, some of which havebeen addressed, with evidence of recovery of some affectedspecies (e.g. the humpback whale population is recoveringstrongly after being decimated by whaling and the southern<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> green turtle stock is increasing aftercommercial harvest in the first half of the 1900s).Beaches, especially on islands such as Raine Island, are importantnesting areas for threatened marine turtle species. (Photo courtesyof J.E.N. Veron)Mean number of sharks per hectareA76543210HabitatProtectionFigure 2.2MarineNationalParkMarine Park ZonePreservationMean number of trout per hectareB2520151050HabitatProtection<strong>Reef</strong> shark and coral troutdensities across zones 2MarineNationalParkPreservationMarine Park ZoneThe density of both (A) reef sharks (grey reef, whitetip reef, silvertipand blacktip reef sharks) and (B) adult common coral trout in theHabitat Protection Zone (open to fishing) is much reduced comparedto that in the Marine National Park and Preservation Zones (closedto fishing). With regard to the two zones that are closed to fishing,the recorded differences in density are likely to be the result of illegalactivity in the Marine National Park Zone. All study reefs were in theTownsville region. The black bars indicate the standard error aroundthe mean.Number of dugongs40 00035 00030 00025 00020 00015 00010 00050000Figure 2.31960197019801985198619871988198919901991199219931994199519961997199819992000200120022003200420052006Remote coast (survey) Urban coast (survey) Urban coast (hindcast)Dugong populations in the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> 3 4 5There is serious concern for the threatened dugong. The dugongpopulation of the ‘urban coast’ of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> (fromCooktown south) may have stabilised, but is about three per centof its size about 40 years ago. The drastically reduced populationis, historically, as a result of commercial hunting and incidentalbycatch in large mesh (gill) nets, and more recently because of thecumulative pressures of habitat loss, incidental capture in large mesh(gill) nets, boat strikes, illegal hunting (poaching), unsustainabletraditional hunting, disease and ingestion of marine debris. ‘Remotecoast’ populations (north of Cooktown) have been relatively stablesince aerial surveys began in 1985. The hindcast modelling of the‘urban coast’ population (dark blue line) was based on the incidentaltake of dugongs in shark control program nets since the early 1960s,which was used as an index of the change.AssessmentcriteriaHabitatsto supportspeciesPopulationsof speciesand groups ofspeciesSummaryFor most of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, habitats appear to be intact. Some inshorehabitats (such as coral reefs) have deteriorated, caused mostly by reduced waterquality and rising sea temperatures. This is likely to have affected species that rely onthese habitats. Little is known about the soft seabed habitats of the lagoon, openwaters or the deep habitats of the continental slope.Populations of almost all known <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> species or groups of speciesappear to be intact, but some populations such as dugongs, as well as some speciesof shark, seabirds and marine turtles, are known to have seriously declined, duemainly to human activities and declining environmental conditions. Many speciesare yet to be discovered and for many others, very little is known about their status.<strong>In</strong> time, more populations are likely to decline. Populations of some formally listedthreatened species have stabilised but at very low numbers; other potentiallythreatened species continue to be identified.VerygoodAssessment GradeGoodPoorVerypoorBIODIVERSITY4

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!3ECOSYSTEM HEALTHThe concept of ecosystem health is associated with one ofnormality: healthy ecosystems are more-or-less unchangedor natural. <strong>In</strong> the case of marine environments, where thereis usually little historic data, an ecosystem can easily bedescribed as healthy or even pristine, when it may in factbe changing, usually for the worse (that is, the ‘baseline’ ofwhat is considered normal has shifted).Many of the key physical, chemical and ecological processesof the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem are changing and this isnegatively affecting the health of the ecosystem.Physical and chemical processes <strong>In</strong>creased sedimentationand inputs of nutrients and pesticides to the ecosystemare affecting inshore areas (figure 3.1), causing increasedalgal growth, accumulation of pollutants in sediments andmarine species, reducing light and smothering corals. Seatemperatures are increasing because of climate change,leading to mass bleaching of corals; and increasing oceanacidity is affecting rates of calcification (figure 3.2). Thesephysical and chemical processes combined are essential tothe fundamental ecological processes of primary productionand building coral reef habitats on the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.Ecological processes It is considered that the overall foodweb of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is being affected by declinesin herbivory in inshore habitats because the urban coastdugong population is a fraction of its former population;in predation on reef habitats because of potential <strong>Reef</strong>widedifferences in coral trout and shark numbers on reefsopen and closed to fishing; and in particle feeding on reefhabitats because of the reduction in at least one species ofsea cucumber. Importantly, populations of herbivorous fishare healthy - they play an important role in maintaining the¬ATotal Suspended Solids(2008)¬BDissolved <strong>In</strong>organic Nitrogen(2008)Very LowLowMediumHighVery HighVery LowLowMediumHighVery HighCooktownCairns !<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Region<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>catchmentCooktownCairns !<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Region<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>catchmentTownsville!Townsville!Charters TowersBowenProserpineCharters TowersBowenProserpineQLD!MackayQLD!MackayClermontRockhampton !Gladstone !ClermontRockhampton !Gladstone !Bundaberg !Bundaberg !MaryboroughMaryborough0 300Gympie0 300GympieKilometresKilometresSDC090414 3.7BSDC090414 3.11BFigure 3.1 Modelled exposure to sediments and dissolved inorganic nitrogen, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2008 6These maps show the modelled exposure of the ecosystem to total suspended solids (A) and dissolved inorganic nitrogen (B) in 2008. Over the past150 years sediment inflow onto the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> has increased four to five times, and five to 10 fold for some catchments. <strong>In</strong> addition, dissolvedinorganic nitrogen and phosphorous continue to enter the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> at greatly enhanced levels, two to five times for nitrogen and four to10 times for phosphorus relative to pre-European settlement. The coastal zone is clearly the part of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> most exposed to increasedsedimentation and nutrients, especially areas close to river mouths.5GREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong> IN BRIEF

1.8such as algal blooms, may indicate the ecosystem is underincreasing pressure. At the same time, the occurrence ofintroduced marine species adjacent to the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Region is increasing.Calcification (g/cm 2 /yr)1.71.61.51.41900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000Number of reefs25201510Figure 3.2Changes in calcification in Porites spp.,<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 1900-2005 75This graph shows an overall decrease in the rate of calcification inPorites corals on the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> since 1900. Since 1980, therehas been a dramatic decrease in the calcification rate, which has beenattributed to increasing acidification and increasing sea temperaturestress. The light blue bands indicate 95 per cent confidence intervalsfor comparison between years, and the green bands indicate 95 percent confidence intervals for the predicted value for any given year.Three hundred and twenty-eight colonies from 69 reefs were sampledthroughout the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. (g/cm2/yr =grams per squarecentimetre per year).Figure 3.30COTSoutbreaksopen to fishingNo COTSoutbreaksMarine Park Zoneclosed to fishingCrown-of-thorns starfish (COTS)outbreaks across zones, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong>, 1994-2004 8ecological balance between algae and coral on reefs. Thereis little known about trends in many key ecological processessuch as microbial processes, primary production, symbiosis,competition and connectivity.Outbreaks of disease, introduced species and pestspecies The incidence of coral disease may be increasingin some areas and it appears that human impacts haveincreased the frequency and severity of crown-of-thornsstarfish outbreaks (figure 3.3). Outbreaks of other species,Outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish have been one of the majorcauses of coral death and reef damage on the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> sincesurveys began in the 1960s. The general scientific view is that occasionaloutbreaks are to some extent natural, but that human impacts haveincreased their frequency and severity. There are significantly fewercrown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) outbreaks in zones closed to fishing(green bars) in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. For both zones open to fishing(blue bars) and zones closed to fishing, the graph shows the numberof surveyed mid-shelf reefs for which an outbreak was recorded atsome time between 1994 and 2004 and those where no outbreak wasrecorded.Effects of predation on preyspecies, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>35AssessmentcriteriaPhysicalprocessesSummaryThe physical processes of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> are changing, in particularsedimentation and sea temperature. Further changes in factors such as seatemperature, sea level and sedimentation are expected because of climate changeand catchment runoff.VerygoodAssessment GradeGoodPoorVerypoorChemicalprocessesFor much of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, the chemical environment has deterioratedsignificantly, especially inshore close to developed areas. This trend is expectedto continue. Acidification of all <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> waters as a result of increasedconcentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide is an emerging serious issue which islikely to worsen in the future.EcologicalprocessesMost ecological processes remain intact and healthy on the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, butfurther declines in physical and chemical processes are expected to affect them in thefuture. There is concern for predation, as predators are much reduced in many areas.Populations of large herbivores (such as dugongs) are severely reduced, howeverpopulations of herbivorous fish remain intact.Outbreaksof disease,introducedspecies andpest speciesOutbreaks of diseases appear to be becoming more frequent and more serious onthe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. Outbreaks of pest species appear to be above natural levels insome areas.ECOSYSTEM HEALTH6

LQM-071WOSD Menu Contents4) PIN4- Application : For all available inputs.- Value Range : See Chart 1.- Default Value : “R TLY C4”- Function : Selects function for REMOTE PIN4.7” <strong>In</strong>tegrated multi format HD Quad input monitors 165) PIN5- Application : For all available inputs.- Value Range : See Chart 1.- Default Value : “G TLY C4”- Function : Selects function for REMOTE PIN5.6) PIN6- Application : For all available inputs- Value Range : See Chart 1.- Default Value : “ACT SEL”- Function : Selects function for REMOTE PIN6.7) PIN7- Application : For all available inputs.- Value Range : See Chart 1.- Default Value : “PWR STBY”- Function : Selects function for REMOTE PIN7.

Number ofindividual ships500011 00010 0009000400080007000300060005000200040001997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008Ships Voyages Trend in ships Trend in voyagesNumber of voyages% of respondents80706050403020100swimmingfishingmotorisedboatingsnokelling sailing diving jetskiingVisitor activities2003 2007 2008Figure 4.3Shipping activity in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong>, 1997–2008 11Figure 4.4Main activities of visitors to the <strong>Great</strong>12 13<strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>There are 10 major ports along the coast of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>and the inner shipping route is a vital part of the Queenslandshipping industry. Over the last 10 years, shipping on the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> has increased - both the voyages undertaken andthe individual ships that operate in the Region. Improvementsin shipping management have resulted in fewer major shippingincidents, despite this increase in traffic. (A voyage is defined asone passage through a section of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>.)Fishing provides opportunities for recreation, resourcesfor the seafood industry, and generates regionaleconomic value. There is limited information aboutmany targeted species and of the survival success ofdiscarded species resulting in a poor understanding ofthe ecosystem effects of fishing.Adjacent ports and shipping through the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> service central and northern Queensland industriesand communities. Most routine shipping activities havenegligible consequences. Dredging and construction ofport facilities can have significant but localised impacts.The impacts of recreation (not including fishing) aremainly localised in inshore areas. Visitors to the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> are consistently very happy with their visitand would recommend the experience.Scientific research improves understanding of the<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> and allows management to be basedupon the best available information. Its impacts areconcentrated primarily around research stations.People enjoy swimming, fishing, boating and snorkelling when theyvisit the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. A survey of households conducted in2008 estimated that 14.6 million recreational visits were made tothe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Marine Park in the previous 12 months byresidents living within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> catchment. Visitorsare consistently satisfied with their <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> experienceand almost all people are satisfied with or unconcerned aboutthe number of other people or vessels they see during their visit.About 60 per cent of recreational visitors visit the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>between one and 10 times in a year, but a small proportion (about15 per cent) visit the area more than 50 times a year.Traditional use of marine resources providesenvironmental, social, economic and cultural benefitsto Traditional Owners and their sea country. It involvesa range of marine species (some of conservationconcern) but levels of take are unknown. Poachingby non-Traditional Owners is a concern for TraditionalOwners and management agencies. Traditional Owneraspirations are being increasingly recognised andformalised in law.Declines in many coral reef ecosystems around the worldare likely to increase the commercial and non-commercialvalue placed on components of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> andpotentially alter use patterns in the future.AssessmentcriteriaBenefits of useSummaryUse of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> contributes strongly to the regional and nationaleconomy and local communities. Its economic value is derived almost exclusivelyfrom its natural resources, either through extraction of those resources or throughtourism and recreation focused on the natural environment, and would be affectedby declines in those resources. Millions of people visit the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> everyyear and are very satisfied with their visit. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is valued wellbeyond its local communities, with strong national and international scientificinterest. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is of major importance to Traditional Owner culture.Some users financially contribute to management.VerygoodAssessment GradeGoodPoorVerypoorVery lowimpactLowimpactHighimpactVery highimpactImpacts of useThe impacts of different uses of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> overlap and are concentratedinshore and next to developed areas. There are some concerns about localisedimpacts and effects on some species. <strong>In</strong> particular, species of conservation concernsuch as dugongs, some bony fish, sharks, seabirds and marine turtles are at risk,especially as a result of fishing, disturbance from increasing use of coastal habitats,illegal fishing, poaching and traditional use of marine resources. There is evidencethat fishing is also significantly affecting the populations of some targeted species.The survival success of non-retained species is not well understood, nor are theecosystem effects of fishing.COMMERCIAL AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE8

5FACTORS INFLUENCINGTHE REEF’S VALUESThe experience of the last two decades has shown that muchof what will happen to the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> in the future willbe determined by factors external to it and to Australia. Thisassessment of the factors that currently and are projected toinfluence the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>’s environmental, economicand social values addresses the three major external factors –climate change, catchment runoff and coastal developmentplus the influence of direct use of the Region.Many of the threats from both the external factors and thosefrom direct use within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> are combiningto cause serious impacts on the ecosystem. All these factorsare significant to the ecosystem’s future functioning andresilience.Climate change Impacts from climate change have alreadybeen witnessed and all parts of the ecosystem are vulnerableto its increasing effects, with coral reef habitats the mostvulnerable. The average annual sea surface temperature onthe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is likely to continue to rise over thecoming century and could be as much as 1 to 3°C warmerthan the present average temperature by 2100. <strong>In</strong> the lastdecade there have been two severe mass coral bleachingevents resulting from prolonged elevated sea temperatures.<strong>In</strong> addition, <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> waters are predicted tobecome more acidic with even relatively small increasesin ocean acidity decreasing the capacity of corals to buildskeletons (figure 5.1) and therefore create habitat for reefbiodiversity in general. Sea level on the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>has already risen by approximately 3mm per year since 1991.Changes in the climate also mean that weather events arelikely to become more extreme and severe. Almost all <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> species and habitats will be affected by climatechange, some seriously (figure 5.2).Corals live in partnership with a single-celled algae (zooxanthellae).When corals are under stress, for example when they become too hot,they expel the algae and appear bleached. If they are stressed for toolong or too severely and do not regain their algae, they will die.Figure 5.1Predicted changes in conditions suitable forcalcification 14<strong>In</strong> the long-term, ocean acidification is likely to be the most significant climatefactor affecting the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem. Chemical changes in theocean have already decreased oceanic pH by 0.1 units. From a current pH of8.2 (alkaline), it is predicted that the ocean’s pH could fall to about 7.8 (stillslightly alkaline) by 2100. With continuing acidification of the oceans, theareas where conditions are suitable for the building of shells and skeletonswill shrink and ultimately disappear. Coral reefs are shown as pink. (Modifiedby permission of American Geophysical Union. From Cao and Caldeira, 2008 15 )Coastal development Coastal development, primarilydriven by mining, industry and population growth, is stillsignificantly affecting coastal habitats that support the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> (figure 5.3), connectivity between habitats andthe water quality of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. <strong>In</strong> the past 150years, the area of the catchment that is intensively farmedhas quadrupled. Over the same period, 53 000 mining leaseshave been granted in Queensland, with more than 3000current as at October 2008. Mining and industrial activityhas driven population growth throughout the catchmentat rates faster than the Australian average, especially alongthe coast. The current population of the catchment is9GREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong> IN BRIEF

Sea temperatureincrease (°C)321Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (ppm)380 400 450 500 550Ocean pH changesince pre-industrial-0.1-0.2-0.3Sea levelincreasesea level increase if contribution from ice sheet melting greater than expected11cm18-38cmCyclones andtropical storms<strong>In</strong>creasing occurrence ofsevere tropical cyclonesGroups of speciesProjected vulnerabilityCoralschange to more thermallytolerant assemblagesreduced density and diversity of coralshard corals functionally extinctSeabirdsFishreduced foraging success andincreased nesting failureloss of many coral-associated speciesMarine reptilesincreasing temperatures affect nesting successPlanktonMicrobesMarine mammalsSeagrassesMacroalgaecompositional shifts due to changes in ocean circulation,nutrient regimes and ocean acidificationvulnerable but have greater capacity for adaptation than other groupsvulnerable due to effects onfood resourcessensitive to increasing temperatures andextreme weather eventsreefs increasingly dominated by fleshy and turfing macroalgae(but calcareous forms impacted by ocean acidification)Habitats<strong>Reef</strong> habitatsreefs remain coral-dominatederosion exceeds calcificationreefs eroding rapidlyIslandsCoastal habitatsOpen waterhabitatsSeabed habitatssensitive to sea level rise, changes to ENSO, increasing air temperature and changing rainfall patternsvulnerable to sea level rise, changes to rainfall patterns andflood events, and increasing sea temperaturemoderate vulnerability, mainly due to sensitivity of plankton toenvironmental changeHalimeda beds affected byocean acidification380 400 450 500 550LowModerateHighVery highFigure 5.2Projected vulnerabilities of components of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem to climate changeThis diagram shows projected vulnerability across a range of carbon dioxide concentrations. Changes in sea temperature, pH and sea levelare indicative only, intended to demonstrate the scientific uncertainty around the likely values. The worst case scenario presented (550ppm) isequivalent to the <strong>In</strong>tergovernmental Panel on Climate Change scenario B1 which was predicted to be reached by about 2100. (Figure adapted fromvalues presented in IPCC 2007 16 , Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007 17 , and Johnson and Marshall 18 )FACTORS INFLUENCING THE REEF’S VALUES10

140Discharge-weighted load(kg per megalitre)% of habitat remaining120100806040200MangrovesNo data availableRiparianWetlandsFloodplainCooktownNormanby River!Cairns!Barron RiverNorth Johnstone RiverTully RiverHerbert RiverBurdekin River< 5050 - 100100 - 200> 200Sediment export load(tonnes)< 50 00050 000 - 100 000100 000 - 200 000> 200 000Figure 5.3Normanby Mulgrave-Russell Tully-MurrayBurdekin Pioneer FitzroyLoss of habitats that support the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> 19Important coastal habitats have been largely lost from some majorriver systems within the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> catchment particularlyin more developed catchments such as the Mulgrave-Russell,Tully-Murray and Pioneer. The percentage of habitat remainingis calculated in comparison to the predicted area of each habitatprior to European settlement.QLDTownsville!Charters Towers<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Region<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>catchment0 300Kilometres!!Bowen!ProserpineClermont!Mackay!Rockhampton !Gladstone!!BundabergMaryboroughGympie!!O'Connell RiverPioneer RiverFitzroy RiverSDC090414 5.24about 1 115 000 and it is expected to grow to 1 5771000by 2026 (figure 5.4). A growing population leads to anincrease in infrastructure and services and, if poorly plannedand implemented, these constructions can further modifythe coastal environment and cause sedimentation, waterquality issues and drainage impacts. Mining and industry isalso fuelling growth in ports and shipping with proposalsfor significant expansion in at least seven of the 10 majortrading ports along the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> coast.Figure 5.5Sediment loads entering the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2005/06 wet season 21Over the past 150 years, sediment inflow onto the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> has increased as a result of extensive forest clearing, especiallyof lowland rainforests and wetlands for sugar cane and of drylandforest for cattle. Catchments with large pastoral areas (Herbert,Burdekin and Fitzroy Rivers) deliver the most sediments to the<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, in the highest concentrations. Soil erosion incane farming areas has reduced since burnt cane harvesting wasreplaced by green harvesting and trash blanketing.Population (thousands)4003002001000Figure 5.4Coastal<strong>In</strong>land1991 2001 2011 2021There are 72 coastal urban centres directly adjacent to the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> coast, with four centres of populations greater than501000. Populations are predicted to continue growing throughoutthe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> catchment, especially along the coast.TotalPopulation growth and predictions inthe <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> catchment 20Catchment runoff The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> receives therunoff from 38 major catchments which drain 424 000 km 2of coastal Queensland. Over the last decade, the decliningquality of water entering the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> has beenrecognised as a major threat to the ecosystem. However,despite improvements in local land management, the qualityof catchment runoff entering the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> continuesto cause deterioration in the water quality in the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> Region. Most sediment entering the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>comes from catchments with large pastoral areas such asthe Burdekin and Fitzroy Rivers (figure 5.5). The load of totalnitrogen delivered to the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is mainly derivedfrom high intensity land use, fertilised cropping and urbanareas. <strong>In</strong> particular, high intensity cropping is the majorcontributor of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (figure 5.6).Only a small proportion of the load is derived from naturalareas. Pesticides from agricultural activities are present in the<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem and their impacts are largelyunknown. These increased concentrations of suspendedsediments and agricultural chemicals are having significanteffects in inshore areas of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, close toagricultural areas. Much continues to be done to improvewater quality entering the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> but it willbe decades before the full benefits are seen. A decline ininshore habitats will have economic and social implicationsfor coastal communities.Direct Use The impacts of different commercial and noncommercialuses of the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> Region overlap andare concentrated inshore and next to developed areas (see11GREAT BARRIER REEF OUTLOOK REPORT <strong>2009</strong> IN BRIEF

Barron RiverDischarge-weightedNutrient load (kg per megalitre)2516North Johnstone RiverNutrient species< 0.30.3 - 0.60.6 - 0.9> 0.9Macroalgae cover20151051412108CooktownQLD!Cairns!Townsville!Charters Towers<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>Region<strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>catchment0 300KilometresSDC090414 5.21Figure 5.6!!Bowen!ProserpineClermont!Tully RiverMackayHerbert RiverBurdekin River!Rockhampton !Gladstone!PN!BundabergMaryboroughGympieDONDINNutrient loads entering the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>, 2005 dry season and!!PPDOPDIPO'Connell RiverPioneer RiverHard coral richness5 10 15 20 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.211010510010095909080855 10 15 20 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2Secchi depth (m)Chlorophyll μg/LThe effect of declining water quality onFigure 5.7Changes in water quality affect the biodiversity of reef systems. Higherconcentrations of pollutants such as suspended sediments, nitrogenand phosphorus, indicated by higher chlorophyll concentrations andlower water clarity (measured as reduced secchi depth readings),result in more macroalgae and less hard coral diversity. Such ashift drastically affects the overall resilience of the ecosystem as adominance of macroalgae reduces the chance for new hard corals toestablish and grow. Blue shading indicates 95% confidence intervals.2005/06 wet season 21 Chapter 4). Direct use of the Region is likely to be havingthe ecosystem 22 12The total nutrient load delivered into the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> is nowgreatly increased. Most nutrients flowing into the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong> are from the wetter, more intensively cropped catchments(Barron, North Johnstone and O’Connell Rivers). PN - particulatenitrogen, DON – dissolved organic nitrogen, DIN – dissolvedinorganic nitrogen, PP – particulate phosphorous, DOP – dissolvedorganic phosphorous, DIP – dissolved inorganic phosphorous.minor, if any, impact on many ecosystem processes andsome uses may have positive benefits through improvingunderstanding and contributing to management. However,there are some key groups of species and ecological processesthat are affected by direct use including fish populations,some species of conservation concern, predation, herbivoryand particle feeding.AssessmentcriteriaImpact onenvironmentalvaluesImpact oneconomicvaluesImpact onsocial valuesSummaryClimate change, particularly rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification, hasalready affected the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem and over the next 50 years it islikely to significantly affect most components of the ecosystem. The <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong><strong>Reef</strong>, especially much of its inshore area, is being affected by increased nutrients,sediments and other pollutants in catchment runoff, mainly from diffuse agriculturalsources, despite recent advances in agricultural practices. Coastal development iscontributing to the modification and loss of coastal habitats that support the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong>. As the coastal population continues to grow there will be increasing useof the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> and therefore the potential for further damage. Direct useof the Region is impacting on some environmental values.Changes to the <strong>Great</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> ecosystem are likely to have serious economicimplications for reef-dependent industries, such as tourism and fishing, and foradjacent communities. Perceptions about the health of the ecosystem also affect itsattractiveness for tourism and recreation and, thus, its marketability. An increasingcoastal population is likely to increase the economic value of <strong>Reef</strong>-based activities.The economic benefits of direct use will be affected by the impacts of externalfactors.An increasing coastal population is likely to increase recreationaluse of the Region and change people’s experiences of the <strong>Great</strong><strong>Barrier</strong> <strong>Reef</strong> with increased congestion at popular recreationlocations and competition for preferred sites. A decline in inshorehabitats as a result of polluted water will have social implicationsfor dependent industries and coastal communities. TraditionalOwners are concerned about rising temperatures altering theseasonality and availability of marine resources as well as thepotential loss of totemic species.Assessment GradeVery low Lowimpact impactHighimpactVery highimpactFACTORS INFLUENCING THE REEF’S VALUES