History of Shipwreck Excavation

History of Shipwreck Excavation

History of Shipwreck Excavation

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Roxanna M. Brown<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong>in Southeast Asia

Roxanna M. Brown<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong>in Southeast Asia1 Ayers 1978; Keith 1979, 1980.2 Liu Xinyuan 1998 and 1999.The Belitung wreck is a recent addition tothe large, and continuously growing, corpus<strong>of</strong> maritime archaeological sites discovered inSoutheast Asia (cf. fig. 1). This spate <strong>of</strong> underwaterexploration largely began three decadesago in the mid 1970s and continues unabated.Since there is no central repository for informationon the various discoveries, and few shipsare as well documented as the Belitung wreck,it is worthwhile to review the finds in general.The sorts <strong>of</strong> primary data <strong>of</strong>fered by underwaterarchaeology in Southeast Asia are certain tohave an impact on a variety <strong>of</strong> ongoing historicaldebates. These debates involve questions aboutchanges in shipbuilding techniques and routesover time, ship sizes, and the extent and content<strong>of</strong> trade in Asia. The wrecks <strong>of</strong>fer invaluable datarelevant to cycles <strong>of</strong> commerce, and they mayhelp answer questions about the spread <strong>of</strong> religions.<strong>Shipwreck</strong> cargoes also provide a bountifulmeans to hone a more definitive chronology<strong>of</strong> trade ceramics. Land sites rarely yield dates forceramics so precise as potentially possible fromshipwrecks. Indeed, it is analysis <strong>of</strong> shipwreckcargoes that is beginning to <strong>of</strong>fer chronologiesthat can be applied to land sites.One <strong>of</strong> the most intriguing and enduring questionsin Chinese ceramics concerns the date andcircumstances that led to the introduction <strong>of</strong>blue-and-white ceramics at the Jingdezhen kilns<strong>of</strong> Jiangxi province. Thus the eyes <strong>of</strong> scholars <strong>of</strong>Chinese art from all over the world immediatelyturned to Korea when a shipwreck with a cargo<strong>of</strong> Chinese trade ceramics was surveyed and partiallyexcavated in 1976. 1 Coins retrieved fromthe site suggested that the ship sailed in the earlyfourteenth century, yet the extensive ceramiccargo did not include blue-and-white. As a result<strong>of</strong> the Sinan wreck finds, scholars concluded thatJingdezhen blue-and-white was not exportedbefore about 1325. This conclusion is supportedby recent research at Jingdezhen itself. Chinesearchaeologists now say that blue-and-white fromJingdezhen was first exported in 1328. 2 Evidencefrom the land thus validates and corroboratesevidence from the sea.A date for the earliest export <strong>of</strong> blue-and-whitefrom Jingdezhen is only one aspect <strong>of</strong> the history<strong>of</strong> cobalt use in Asia. Cobalt produced the blueglaze seen on many Tang dynasty burial wares,but that glaze is quite different from the glazes<strong>of</strong> Jingdezhen. The colourful Tang dynasty glazesare low-temperature lead glazes. The glazes <strong>of</strong>Jingdezhen are high-temperature ash glazes.The colourful Tang ceramics are earthenware,while underglaze blue decoration at Jingdezhenis applied to high-fired stoneware and porcelain.Following decades <strong>of</strong> claims by a few ardentChinese collectors that there were underglazeblue wares in the Song dynasty, archaeologists42 <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia

eventually did find evidence for pre-Jingdezhenblue-and-white. In fact, the finds are also pre-Song dynasty. Very old blue-and-white sherdswere discovered first in 1975 and then in the1980s at Yangzhou, Jiangsu province, and theywere assigned to the ninth century when theport <strong>of</strong> Yangzhou was frequented by Arabs andPersians. They are believed to have been made atthe Gongxian kilns, Henan. 3 Again, finds fromthe sea corroborate evidence on land, for thecargo <strong>of</strong> the Belitung wreck <strong>of</strong>fers three pristine,unbroken examples <strong>of</strong> Tang dynasty blue-andwhitethat resemble the finds from Yangzhou andGongxian (nos 107–109).Mysteries remain <strong>of</strong> course. No connection hasyet been established between the ninth- andthe fourteenth-century blue-and-white wares.Whether blue-and-white was produced in theyears between is unknown. The dishes aboardthe Belitung wreck revive these old questionsabout the origins <strong>of</strong> blue-and-white and makethe discussions ever more interesting. 4In 1974, shortly before the Sinan wreck wasfirst discovered by Korean fishermen, anothershipwreck, this one from the fifteenth century,was discovered by fishermen in the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Thailand.Identified as the Ko Khram (or Sattahip)wreck, it carried a surprising mixture <strong>of</strong> trade ceramicsfrom southern China, northern Vietnam,Champa (a former kingdom located in centralVietnam) and Thailand. 5 Like the Sinan wreck,it also did not yield Chinese blue-and-whitewares, but it represents a time in the fifteenthcentury when blue-and-white was not exportedto Southeast Asia. The Thai ceramics, moreover,came from three different production centres.For the first time here was evidence that thesethree centres were all active at the same time. Thelong held theory that the Sukhothai kilns closedwhen the Sawankhalok kilns opened had to bediscarded. In addition to continuous re-assessments<strong>of</strong> this vessel and its cargo, the discoveryand documentation <strong>of</strong> the Ko Khram wreck canbe used as a signpost for the beginnings <strong>of</strong> anamazing series <strong>of</strong> shipwreck finds in SoutheastAsia. Only two sites were documented prior to1974, and more than a hundred have been reportedsince then. An average four or five moreare discovered every year.The first <strong>of</strong> the two sites known prior to 1974involves a small vessel assigned to the third–fifthcenturies found in the Pontian River, Malaysia.In addition to being the subject <strong>of</strong> the earliestreport on an antique boat in Southeast Asia, thePontian vessel remains the oldest known vesselin Southeast Asia. 6 The second site involves threevessels <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth–nineteenth centuriesthat were discovered together at Johore Lama,Malaysia in the 1950s. 73 The archaeological data onpre-fourteenth-century blue-andwhitein China is reviewed byRita Tan in Gotuaco et al. 1997,xiii–xv.4 The tie between ninth- andfourteenth-century Chineseblue-and-white may have to dowith customer preference. Blueis a popular colour in the MiddleEast.5 The Ko Khram is the subject<strong>of</strong> numerous articles; see, forinstance, Brown 1975–76, Howitz1977, Green 1981, Rooney 1981,Green and Harper 1987.6 The Pontian boat is featuredin articles by Evans (1927) andGibson-Hill (1952). Manguin(1996) refers to it as an example<strong>of</strong> traditional early SoutheastAsian boat construction.Booth (1984) gives the results<strong>of</strong> radiocarbon dating on theboat as 293 +/-60. The finds arealso summarized in Brown andSjostrand 2002.7 Sieveking et al. 1954.<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia 43

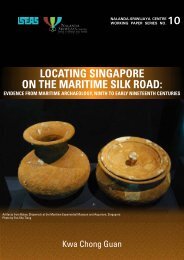

INDIABANGLADESHCHINAMYANMAR(BURMA)VIETNAMLAOSTHAILANDHoi AnINDIAN OCEANKo KradatCAMBODIASamed Ngam Prasae RayongSRI LANKAPhu Quoc IIKo SamuiPhu Quoc/VungtauSingtaiCa MauBinh ThuanVung TauLongquanMALAYSIAXuandeRoyal NahaiNanyangDesaruTuriangSINGAPOREINDONESIABELITUNGMaraneiIntanJava Sea WreckINDONES44 <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia

Bai Jiao ITAIWANSan IsidroPHILIPPINESThitu ReefBRUNEIPACIFIC OCEANMALAYSIAINDONESIAINDONESIAPAPUA-NEW GUINEADONESIAFig. 1 <strong>Shipwreck</strong> sites in theSouth China Sea (Map courtesy<strong>of</strong> ECAI Southeast Asia).<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia 45

<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong>in Southeast Asia8 Christie’s 1984a, 1984b and1985.9 In a popular book for hopefullocal treasure hunters, Tony Wells’<strong>Shipwreck</strong>s & Sunken Treasure inSoutheast Asia (1995, 38), for instance,the story is featured underthe heading ‘The Geldermalsen’sFabulous Nanking Cargo’. Theship, which was en route fromCanton, China, to the Netherlands,sank on 3 January 1752.10 Liu Benan 1995.11 See Christie’s 1984a, 1984b,1985, 1986, 1992, 1995 and 2004;Butterfields 2000; Nagel Auctions2000.<strong>Shipwreck</strong> sites have been located and at leastpartially investigated both in internationalwaters and within the territorial waters <strong>of</strong> almostall the countries <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia (cf. fig. 1).Sites in international waters are investigated byprivate entrepreneurs who base their salvagerights on international laws <strong>of</strong> the sea. Sites interritorial waters have been excavated by the relevantnational authorities alone or sometimes inconjunction with archaeologists from abroad ortogether with private companies. Sometimes thework <strong>of</strong> excavation is wholly contracted out toa private company, and sometimes the countrysimply issues an excavation permit to salvors fora fee. In Vietnam, the national salvage companyis usually involved. In Thailand, the UnderwaterArchae ology section <strong>of</strong> the Fine Arts Departmentdirects excavations. There is a wide range<strong>of</strong> possibilities. The extent <strong>of</strong> published documentation<strong>of</strong> a wrecksite also varies considerably.Sometimes there is a full excavation reportbut more <strong>of</strong>ten either the archaeology or the datarecording (or both) is incomplete. Yet there is aclear, loud message from experience: when fishermenor sports divers simply extract artefactsfrom a wreck, when there is no documentationwhatsoever, these objects are less valuable botharchaeologically and commercially.In the case <strong>of</strong> the first shipwreck ceramics tobe sold publicly, 8 there were questions from theacademic community about whether the piecesactually came from a shipwreck or not. Thuswhen the same entrepreneur, Michael Hatcher,found a second shipwreck, the Dutch EastIndies Company’s Geldermalsen, the excavationwas documented with reports and underwaterphotography. The sale <strong>of</strong> Geldermalsen finds asThe Nanking Cargo at Christie’s Amsterdam in1985 is well remembered. 9 The event fired theimaginations <strong>of</strong> treasure hunters worldwide, itis continually cited as an example <strong>of</strong> great richesunder the sea (even though no other shipwreckcargo in Southeast Asia has brought as muchmoney) and Chinese authorities openly admitthat the Geldermalsen sale led directly to thecreation <strong>of</strong> the Research Laboratory <strong>of</strong> UnderwaterArchaeology at Beijing <strong>History</strong> Museumin 1987. 10 Actually, relatively few cargoes fromshipwrecks in Southeast Asia have made it toauction houses. Five ( Hatcher’s Ming wreck, theGeldermalsen, the Diana, the Vung Tau cargo,and Binh Thuan) have been sold by Christie’s, asixth ( Hoi An wreck) was sold by Butterfields inSan Francisco, and a seventh ( Tek Sing) was soldin Germany at Nagel Auctions. 11 On the whole,commercial viability for shipwrecks from SoutheastAsia is rare.Besides a cargo <strong>of</strong> more than 100,000 pieces <strong>of</strong>high-quality Chinese porcelain, the Geldermalsenyielded 125 shoe-shaped gold bars. Gold on ship-46 <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia

wrecks in Southeast Asia is however normallyrare, particularly on non-European vessels. Thegold dishes recovered from the Belitung wreck(nos 2–4) are extraordinary, as is the gold jewelleryfrom the Intan wreck that will be mentionedshortly. One wonders if such fine gold dishes asthose carried aboard the Belitung wreck were astandard item <strong>of</strong> trade in the ninth century. Butuntil other ships from this early date are found,one can only speculate. Judging by the rarity<strong>of</strong> the types <strong>of</strong> the Chinese Changsha ceramicsaboard the Belitung wreck at land-based sites,the gold vessels were perhaps equally rare. Allevidence suggests this was an unusually richcargo. Only about fourteen per cent <strong>of</strong> the importedChinese ceramics from the ninth–tenthcenturies at Palembang, the site <strong>of</strong> the old capital<strong>of</strong> Srivijaya on Sumatra in the seventh–eleventhcenturies, for instance, are from Changsha.Most <strong>of</strong> the Palembang debris fragments fromthis time are Yue, Yue type and Guangdongwares. 12 Ceramics from Changsha have not beenre covered from any other wrecksite.It is impossible to be precise about an actualnumber for the shipwrecks found to date inSoutheast Asia. One problem is geographicallimits. There are a number <strong>of</strong> Portuguese andDutch wrecks in the Indian Ocean <strong>of</strong>f the coast <strong>of</strong>Africa for instance, the remains <strong>of</strong> a Portuguesevessel in the Seychelles, and a few other Europeanvessels may lie in the depths <strong>of</strong> Galle harbor in SriLanka. 13 Many <strong>of</strong> them were en route from Chinaand Southeast Asia to Europe and their cargoesinclude Southeast Asian goods. Old Spanishgalleons, en route from Manila to Acapulco inthe Americas, have also been investigated in thePacific Ocean and even <strong>of</strong>f the shores <strong>of</strong> Californiaand Mexico. 14 There have also been a number<strong>of</strong> excavations in China such as the Quanzhouship <strong>of</strong>f the South China coast. Excavated in1974, the Quanzhou vessel <strong>of</strong>fers a model for theconstruction <strong>of</strong> southern Chinese vessels in thethirteenth century, and it carried the remains <strong>of</strong>cargo from Southeast Asia. 15 Fragments <strong>of</strong> Thaiceladon that must have been loaded in SoutheastAsia were recovered in the excavation <strong>of</strong> anothervessel in Hong Kong. 16 There are also ships, suchas the Batavia 17 and Vergulde Draeck 18 that sank<strong>of</strong>f the coast <strong>of</strong> Western Australia. All these canbe included in a list <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia sitesThe one major area where no wrecksites have yetbeen documented is the waters <strong>of</strong> Burma and theeastern shores <strong>of</strong> India. Research on underwatersites along the western coast <strong>of</strong> India is almost asscanty. A single maritime investigation by Indianarchaeologists in 1997–1999 revealed only theremains <strong>of</strong> an unidentified vessel from the seventeenth–eighteenthcenturies. 19 For this reason theBelitung wreck <strong>of</strong>fers a further point <strong>of</strong> significance.It originated in the western Indian Ocean12 Personal communication fromPierre-Yves Manguin.13 Examples include the Santiago(sank 1585; Martin 2001) <strong>of</strong>fMozambique; the Santo Antoniode Tanna (1697; see Piercy 1977,1978, 1979, 1981) at MombasaHarbour, Kenya; and three <strong>of</strong>fSouth Africa, the Sao Bento(1554; see Auret and Maggs 1982;Esterhuizen 2000), the Sao Joao(1552; see Esterhuizen 2000);and Witte Leeuw (1613; see Vander Pijl-Ketel 1982). For theSeychelles wrecksite, see Blakeand Green 1986. For informationon the shipwrecks beinginvestigated at Galle, see http://www.hum.uva.nl/galle.14 Remains <strong>of</strong> two Manilagal leons have been found in theMariannas Islands, the NuestraSenora de la Concepcion (lost1638) at Saipan (Mathers andShaw 1993) and the Santa Margaritaat Rota (IOTA Partners 1996,Cuevas et al. 1997). The remains<strong>of</strong> others have been identifiedat Drake’s Bay in California(Shangraw and Van der Porten1981) and near Encinada, Mexico(personal communication fromEdward Van der Porten).15 Salmon and Lombard 1979;Keith and Buys 1981; Green1983a; Li Guoqing 1989.16 Frost et al. 1974.17 Stanbury 1975.18 Green 1977.19 Tripati et al. 2001. Morerecently, the remains <strong>of</strong> aneleventh–thirteenth-centuriesvessel were discovered on land inSouth India; see Pedersen 2003.<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia 47

<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong>in Southeast Asia20 Brown and Sjostrand 2002.The exhibition, entitled ‘MalaysianMaritime Archaeology’,opened in November 2001 andwill be on view at least through2004. The catalogue presents thefirst attempt to place ceramiccargoes <strong>of</strong> the fourteenth–sixteenthcenturies in relativechronological order.(either the Middle East or India), yet there is nostrong corpus <strong>of</strong> shipwreck archaeology there forcomparisons.My personal list <strong>of</strong> wrecksites includes sitesknown to fishermen, sports divers and/or privatesalvors that have not been reported inprint. In some cases there are no public reportsbecause the cargo is not commercially viable. Ifit becomes clear that not even publication willincrease the sales price <strong>of</strong> a cargo sufficiently tocover expenses, the complicated efforts <strong>of</strong> properdocumentation and publication are <strong>of</strong>ten abandoned.The academic world benefits most whencollectors and museums, as well as archaeologists,see value in shipwreck cargoes.While some wrecksites become the subject <strong>of</strong> anewspaper or magazine article and then disappearfrom view, many good articles on shipwreckfinds in Southeast Asia have appeared in TheInternational Journal <strong>of</strong> Nautical Archaeology,and the Internet has become an alternate means<strong>of</strong> publication. A number <strong>of</strong> websites on theWorld Wide Web now feature news and articleson the excavations <strong>of</strong> shipwrecks in SoutheastAsia (Several <strong>of</strong> these websites are listed in thisvolume, p. 753).The few attempts to summarize nautical finds inSoutheast Asia include an indispensable study byJeremy Green and Rosemary Harper, The MaritimeArchaeology <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong>s and Ce ramics inSoutheast Asia (1987), and two volumes inThai with short English summaries, Vidya Intakosaiand Pisit Charoenwongsa (ed.), UnderwaterArchaeology in Thailand (1988) and PisitCharoenwongsa and Sayan Praicharnjit (ed.),Underwater Archaeology in Thailand II: Ceramicsfrom the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Thailand (1990). Any summaryis however quickly out-<strong>of</strong>-date, since more newsites are discovered each year, and sometimesthere is further excavation <strong>of</strong> old sites. Greenand Harper (1987), for instance, mention somethirty-three wrecksites, and this includes variousvessels <strong>of</strong>f Korea (two sites), South China (two),Africa (five), the Seychelles (one) and WesternAustralia (two). My own informal list, which includesthe sites enumer ated in Green and Harperas well as finds through early 2004, numbers175 entries, with 129 <strong>of</strong> them in Southeast Asiaproper.The most recent retrospective on shipwreckarchaeology is being staged as an exhibition atthe Kuala Lumpur National Museum, Malaysia.Accompanied by a catalogue, 20 the exhibitionfeatures eleven vessels. These range from thePontian boat <strong>of</strong> the third–fifth centuries that wasdiscovered in an eroding riverbank to ten wrecksitescovering the fourteenth–nineteenth centuries<strong>of</strong>f the coasts <strong>of</strong> peninsular Malaysia. With48 <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia

<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong>in Southeast Asia27 Flecker 2001a. The Intanartefacts have been given to theMuseum Pusat, Jakarta.28 A newly documentedwrecksite, given the site nameTanjung Simpang, which wasdiscovered <strong>of</strong>f Sabah, EastMalaysia, in December 2003may fill this temporal gap; seewww.mingwrecks.com.29 Ridho and Edwards McKinnon1998.30 Clark et al. 1989.31 Conese 1987.32 Edwards McKinnon 2001.33 Dupoizat 1995.34 Goddio et al. 1997.35 Mathers and Flecker 1997.Dupoizat (1995) assigns theBreaker Reef Shoal ceramics tothe eleventh–twelfth centuriesbut later excavation <strong>of</strong> the JavaSea wreck in Indonesia <strong>of</strong>feredgood evidence for a thirteenthcenturydate. Ceramics from thetwo cargoes are practically identical.So alike are they that one canimagine that the two ships probablyleft Quanzhou port on thesame day. A notable feature <strong>of</strong> thetwo cargoes is that they carriedprimarily Fujian ceramics.Following in time after the Pontian and Belitungwreck vessels, the Intan wreck is the sole site s<strong>of</strong>ar tentatively assigned to the tenth century inSoutheast Asia. This ship, which carried a widemixture <strong>of</strong> Chinese, Middle East and SoutheastAsian goods, appears to have been en route fromSumatra to Java. 27 The Intan finds include Chineseceramics, Indian and/or Southeast AsianMahayana Buddhist objects, gold jewellery,Middle Eastern glass, and a range <strong>of</strong> metal itemsincluding bronze, lead, silver, iron and tin goods– some 13,500 artefacts altogether.None <strong>of</strong> the known shipwrecks can be assignedspecifically to the eleventh century, 28 but theimportant Pulau Buaya wreck in Indonesia 29belongs to approximately the eleventh–twelfthcenturies.Judging from brief, cursory notices, five furtherwrecksites can be tentatively assigned to theapproximate time range <strong>of</strong> twelfth–thirteenthcenturies. None <strong>of</strong> the five has been described indetail. Three, the North Palawan, Bolinao I, andSan Antonio sites, are mentioned in a report ona joint Australia-Philippines survey, 30 with theNorth Palawan site also investigated two yearsearlier. 31 Two others, the Jepara and Karang Cinasites in Indonesia, were mentioned in a lectureat Ceramic Society <strong>of</strong> Indonesia. 32 Neither <strong>of</strong> thetwo Indonesian sites has been <strong>of</strong>ficially investigated,and information on them comes primarilyfrom the antiques market.It should be mentioned that there is very rarelya full accounting <strong>of</strong> any wreck partly because thefishermen who are always the first to discover oldwrecksites are able to retrieve and sell at least aportion <strong>of</strong> the material. Many sites also becomeunknowingly disturbed and their artefacts brokenand scattered because <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> fishingdrag nets.Known shipwrecks from the thirteenth centuryare more numerous. Three wrecksites in SoutheastAsia can be assigned, with fair confidence, tothe thirteenth century, and all three were excavatedwith some care. It is however unfortunatethat no remains <strong>of</strong> a hull were found at any <strong>of</strong>the three sites. They are the Breaker Reef Shoal 33and Investigator Shoal 34 sites in the Philippines,and the Java Sea wreck in Indonesia. 35 Anothervessel, the Quanzhou ship, which was excavated<strong>of</strong>f South China and has already been mentionedabove (p. 47), is also generally included in studies<strong>of</strong> underwater archaeology and shipping for thethirteenth century. The Quanzhou ship presentlyprovides the only example <strong>of</strong> South Chinese shipconstruction for this period.Altogether, as this chapter is being written, abouttwo dozen ships or wrecksites are known inSoutheast Asia from the third–thirteenth centuries.At many <strong>of</strong> these, as well as later sites, parts<strong>of</strong> the actual vessel have been located or not beenreported. In these cases, it is only the remains <strong>of</strong>cargo that are seen and documented. In other50 <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia

cases, remains <strong>of</strong> a ship have been found withoutany associated cargo.The fourteenth century is tricky, and the mostspec tacular possible discovery for the futurewould be a full cargo <strong>of</strong> the highly treasured Yuandynasty blue-and-white ware. For now, no shipwrecksin Southeast Asia fill the gap between theSinan wreck (c. 1325) <strong>of</strong>f Korea and the earliest<strong>of</strong> five shipwrecks that are presently assigned tothe beginning <strong>of</strong> the Ming dynasty (1368–1643).Most intriguingly, no ships anywhere have beendiscovered with a cargo <strong>of</strong> Yuan dynasty blueand-white.36 Partly this can be explained by theirbrief time <strong>of</strong> export that, as mentioned above,Chinese archaeologists now say extends onlyfrom 1328 to 1352, a mere twenty-four years.Nevertheless, one can certainly hope for such adiscovery, since fair numbers <strong>of</strong> Yuan blue-andwhitefound in such places as the Philippine andIndonesian islands show that the ware did travelby sea.While the finds <strong>of</strong> Yuan dynasty blue-and-whiteat land sites in the Middle East and SoutheastAsia hold promise that the pre-Ming cargo mayone day be discovered, there is little hope for asignificant cargo <strong>of</strong> blue-and-white from most<strong>of</strong> the first half <strong>of</strong> the Ming dynasty. For, priorto the Hongzhi reign (1488–1505), Ming blueand-whiteis practically absent from both landand maritime sites. Elsewhere, I have adoptedthe term ‘Ming gap’ to refer to this near absence<strong>of</strong> blue-and-white, which extends from 1352(when Chinese archaeologists say war caused theclosure <strong>of</strong> the Jingdezhen kilns) to the Hongzhireign. 37The ‘Ming gap’ is presently reflected in the findsfrom fourteen shipwrecks with ceramics inSoutheast Asia. Only 50–100 examples <strong>of</strong> blueand-whiteare documented from the fourteencargoes, and all except one example come fromthe years that immediately precede the Hongzhireign. That exception comes from the Rang Kwienwreck (c. 1380–1400) in the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Thailand;the other examples are scattered among the cargoes<strong>of</strong> five wrecks from about 1450–1487. 38 Theuncertainty about the total number <strong>of</strong> finds isdue to confusion over the correct identification<strong>of</strong> the mixture <strong>of</strong> Chinese and Vietnamese blueand-whiteceramics from the Pandanan wreck inthe Philippines. It appears clear, however, that theVietnamese examples recovered outnumber theChinese examples.The shipwrecks also show that the ‘Ming gap’,which strictly refers to the period <strong>of</strong> shortages thatfollows the Ming ban on private overseas tradefrom 1369, is more than a dearth <strong>of</strong> blue-andwhite.The total proportion <strong>of</strong> Chinese ceramics<strong>of</strong> all types on the five known shipwrecks fromabout 1368–1424/30 is approximately thirty–fifty per cent. This is a significant drop from thehundred per cent Chinese monopoly on tradeceramics known from earlier shipwreck cargoes.36 Two collections <strong>of</strong> Yuandynasty sherds may come fromundocumented shipwrecks <strong>of</strong>fSri Lanka and in the Red Sea; seeCarswell 2000, 2001.37 The term ‘Ming gap’ was firstused by Harrisson (1958) to referto an absence <strong>of</strong> early Ming blueand-whiteat Sarawak River deltasites in Borneo, then adopted byme in an article on the Xuandeshipwreck (Brown 1997) andexpanded in scope in my Ph.D.dissertation (Brown 2004).38 The fourteen shipwrecks (cf.pp. 44–45, fig. 1)include RangKwien and Song Doc (both c.1380–1400), Turiang and Ko SiChang II (both c. 1400–1420),Maranei (c. 1420–1430), Nanyangand Longquan (both c. 1424/30–1450), Ko Khram and RoyalNanhai (both c. 1450–1460), Pandanan(c. 1470), Belanakan, PhuQuoc II, Prasae Rayong, and KoSi Chang III (all c. 1470–1487).For information on the individualsites, see Brown 2004, 128,table 25. While the inventory <strong>of</strong>the Rang Kwien artefacts includesthree examples <strong>of</strong> Chineseblue-and-white, two <strong>of</strong> them arealmost certainly intrusive findsfrom the nearby Pattaya site (c.1480–1510). See Brown 2004, pls11–12. The five wrecks with blueand-whitefrom c. 1460–1487are the Royal Nanhai, Pandanan,Belanakan, Phu Quoc II, and KoSi Chang III.<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia 51

<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong>in Southeast Asia39 For a popular, well-researchedhistory <strong>of</strong> these voyages seeLevathes 1994. For the first reporton the ceramics shortages seeBrown 2004.40 The phases are described inBrown 2004, ch. 3.41 Since this is the period <strong>of</strong> theMac dynasty in Vietnam, I havecreated the term ‘Mac gap’ todescribe this situation, see Brown2004. Vietnamese blue-and-whitemakes a brief reappearance inmaritime archaeology in theform <strong>of</strong> 16 jars recovered fromthe Royal Captain Shoal wreckthat belongs to about 1600; seeGoddio 1988, 101.42 One <strong>of</strong> the Pandanan pieces isshown in Loviny 1996, 77, and allfour are shown in Brown 2004,190, pl. 50. For the Brunei junkpieces see L’Hour 2001, 31, 81.43 L’Hour 2001, 31, 81.The ceramics recovered from the five sites aremostly celadon, but there are also monochromebrown and monochrome white wares.While a shortage <strong>of</strong> about fifty per cent basedon land sites, has always been suspected, thenine shipwrecks from about 1424/30–1487 have<strong>of</strong>fered an unexpected surprise. In this periodthe proportion <strong>of</strong> Chinese ware plunges to fiveper cent and usually less. In other words, theperiod <strong>of</strong> greatest shortage follows the famousZheng He ‘treasure ship’ voyages that, except forone later mission in 1433, sailed from China toSoutheast Asia, India and even the coast <strong>of</strong> Africaduring the Yongle reign (1403–1424). 39Maritime archaeology reveals other unexpectedfindings as well. Firstly, shipwrecks from about1380–1580 presently show a valuable provisionalsuccession <strong>of</strong> six phases <strong>of</strong> Thai ceramics from fivedifferent production sites. 40 Secondly, they <strong>of</strong>fer aguide to approximate dates for export from otherareas. Besides Thailand, trade ce ramics were alsoproduced in Vietnam and Burma. Champa warefrom central Vietnam’s Binh Dinh provincehas been recovered in commercial quantitiesfrom the Ko Khram and Pandanan wrecks (c.1450–1470), and in very limited numbers fromthe Ko Si Chang III (c. 1470–1487) and Hoi An(c. 1500–1510) ships (pp. 44–45, fig. 1) that sailedafter the export probably ended with a defeat <strong>of</strong>Champa at the hands <strong>of</strong> Vietnam in 1471. Burmeseceladon ware is most common on Hongzhiperiod shipwrecks (1488–1505) but at least oneexample was recovered from the Pandanan site(c. 1470). Vietnamese ceramics are found alongsidethe earliest maritime finds <strong>of</strong> Thai ceramics,but the period <strong>of</strong> greatest export for Vietnameseware appears to have been about 1470–1510.About 1510 Vietnamese ceramics abruptly disappearfrom shipwrecks for the remainder <strong>of</strong> thesixteenth century. 41<strong>Shipwreck</strong>s also reveal the existence <strong>of</strong> a trade inantiques. Six Yuan dynasty ceramics have beenrecovered from two Ming-dynasty ships – fourexamples from the Pandanan wreck <strong>of</strong> about1470 and two from the Brunei junk <strong>of</strong> about1500. 42 Even earlier evidence for an antiques tradein Asia comes from the previously mentionedSinan wreck. Three Korean pots from the twelfthcentury were found in a cargo <strong>of</strong> Chinese ceramicsfrom c. 1325. Still, it was a surprise twentyyears later to find four Yuan dynasty ceramicsaboard the Pandanan vessel in the Philippines.Then two further Yuan dynasty pieces, a smallblue-and-white jar, and a gourd shaped ewer,were re covered from the Brunei junk. 43 At thetime <strong>of</strong> loss, the Yuan dynasty examples from thePandanan were at least one hundred years oldand those from the Brunei junk were about onehundred and fifty years old.52 <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia

Before moving on to later ships, it is worthmentioning that the Maranei, which probablysailed about 1420, yielded at least seven examples<strong>of</strong> the earliest known Chinese firearms froma maritime context. Two other firearms werefound at the Pandanan site (c. 1460–1500), fivewere found at the Lena Shoal (c. 1490–1500)and seven at the Brunei junk (c. 1505) sites. TheAustralia Tide (c. 1500–1510) <strong>of</strong>fered three moreexamples. 44 All these belong to a time before thePortuguese conquest <strong>of</strong> Melaka in 1511.The Hongzhi reign (1488–1505) is one <strong>of</strong> themost important markers in constructing a relativechronology for the shipwrecks <strong>of</strong> SoutheastAsia. The period is marked by a sudden, extraordinaryoutflow <strong>of</strong> Chinese ceramics, includinga large percentage <strong>of</strong> blue-and-white. With fairconfidence based on mainland Chinese archaeology,at least three ships can be assigned tothe Hongzhi years. 45 These are the Lena Shoaland Santa Cruz wrecks in the Philippines andthe Brunei junk. Each <strong>of</strong> the three ships carriedmore Chinese blue-and-white than seen on allearlier shipwrecks combined. It is instructiveto vi sualize the Hongzhi years as a great bubble<strong>of</strong> Chinese blue-and-white that flowed ontothe Southeast Asian market. For, shortly afterthe Hongzhi years, there appears to have been amoderate fall in export volume that lasted untilthe Ming ban was formally rescinded in 1567.Thai wares alone fill the gap <strong>of</strong> sixteenth-centuryChinese shortages, since the Vietnameseappear to have ceased all export by about 1510.Both Vietnamese and Burmese wares are absentfrom shipwreck cargoes currently assigned to theZhengde reign (1506–1521), and Champa hadceased production some thirty years earlier.After 1567 there are only gentle reminders <strong>of</strong>the golden age <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asian ceramics.Thai storage jars from the Singburi kilns nearAyutthaya are documented on practically everyshipwreck from about 1425 to at least 1727,while Sukhothai ceramics dropped from the exportscene by about 1530–1540 and Sawankhalokceramics disappeared by about 1570–1580. Smallamounts <strong>of</strong> Vietnamese ware from the earlyseventeenth century are known in Indonesia, andseveral Burmese storage jars were recovered fromthe San Diego (1600), a galleon, which sank <strong>of</strong>fManila on 14 December 1600. Otherwise, Chineseware, now predominantly blue-and-white,takes over the ceramics market, and this beginsthe third major division <strong>of</strong> shipwrecks.The two hundred years (c. 1380–1580) <strong>of</strong> primarySoutheast Asian ceramics export dividethe shipwrecks <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia into three largegroups: those that are earlier than ones withSoutheast Asian ceramics, the ones with SoutheastAsian ce ramics, and those that are later. In44 Neither the Maranei norAustralia Tide examples have notbeen published. For the Pandanansee Loviny 1996, 69; for theLena Shoal see Goddio et al. 2002,240–241; 0for the Brunei junk seeL’Hour 2001, II, 152–153.45 See Lam 2002 who supportedthis identification.<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia 53

<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong>in Southeast Asia46 This one is the Gujanganwrecksite in the Philippines,at which the vessel was a local,small, eighteen metres long,stitched-plank ship. Planking,showing carved lugs on the innerside, from the ship is on view atthe Naval Museum in Manila. SeeDizon 2003; Gotuaco 2002.47 For a description <strong>of</strong> the SouthChina Sea technical tradition seeManguin 1984, 1993, 1996.review, the earlier group, which has already beendescribed above, presently includes some twodozen maritime-related sites from the third tothirteenth centuries within the boundaries <strong>of</strong>Southeast Asia. The earliest <strong>of</strong> these sites that includesa ship and associated cargo is the Belitungwreck.The earliest <strong>of</strong> the documented ships with Thaiand Vietnamese Southeast Asian ceramics belongto about 1380–1400, and the latest, whichcarry Thai Sawankhalok ceramics, are probablyno later than about 1580. For the two centuries1380–1580, some thirty-five sites are known, andonly one <strong>of</strong> them has not yielded any SoutheastAsian ceramics. 46Moving on in time, about six sites can be assignedto the Wanli reign (1573–1619), and one <strong>of</strong> them,the San Diego, represents the earliest recoveredremains <strong>of</strong> a European vessel in Southeast Asia.Subsequent shipwreck finds, including aboutfourty sites, for the seventeenth–nineteenthcenturies are then about evenly divided betweenAsian an European ships, with a variety <strong>of</strong>British, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch and Frenchvessels. The few Asian ships for which there areexcavation reports concerning the hull structureappear to be Chinese in this later period, whereasall but one (the Belitung) from the pre-Mingperiod appear to be Indonesian vessels.The Southeast Asian period, on the other hand,<strong>of</strong>fers a mixture <strong>of</strong> Asian vessels. At least three <strong>of</strong>the early ships from the years c. 1400–1424/30are China-built: the Ko Si Chang II, Turiang,and Maranei. This small group is followed by theearliest documented hybrid ships, the Nanyangand Longquan (both 1424/30–1450), whichwere discovered <strong>of</strong>f peninsular Malaysia. HybridSouth China Sea ships combine Southeast Asianhardwood and Southeast Asian constructiontechniques with Chinese ones. 47 China-builtships reappear in maritime archaeology in thesixteenth century, when they seem to have sailedalongside both hybrid ships, which perhapsbelonged to overseas Chinese, and traditionalold lashed-lug vessels from the Philippine andIndonesian archipelagoes.Before closing, I would like to emphasize the necessity<strong>of</strong> caution in drawing ‘conclusions’ fromshipwreck finds. The word ‘accidental’ comesimmediately to mind. The loss <strong>of</strong> ships is alwaysaccidental , and the discovery <strong>of</strong> their remains inmodern times is also accidental. Not all maritimesites yield both cargo and ship remains. Oftenthere is no trace <strong>of</strong> the original hull. The finds54 <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia

may be jettisoned cargo, or else the wood <strong>of</strong> thehull has entirely rotted away. On the other hand,ships are sometimes discovered (usually on land)without any sign <strong>of</strong> cargo. Recovered cargoesare never intact, since the sites are disturbed byfishing activities and divers long before pr<strong>of</strong>essionalobservation and excavation take place.Even then, sites are rarely completely excavated,and it is even rarer that they are adequately documented.Data is always fragmentary. In manycases – my notes contain twenty such under-reportedsites – there is not enough informationto be more precise about age than ‘pre-Ming’,‘Ming’, or ‘later’. Still, the database is growing,since an average five to six new maritime sitesare discovered every year. As mentioned earlier,my own notes include about 175 sites associatedwith Southeast Asia, with 129 <strong>of</strong> them within thegeographical limits <strong>of</strong> Southeast Asia proper.centuries, that precedes the era <strong>of</strong> SoutheastAsia trade ceramics c. 1380–1580. The thirdgroup includes sites from the late sixteenththrough nineteenth centuries. For now, the Belitung<strong>of</strong>fers the earliest cargo recovered at leastpartially intact, and it is also the sole ship fromthe Indian Ocean so far documented in SoutheastAsia. Alongside more than a hundred othermaritime sites already known in Southeast Asia,the Belitung <strong>of</strong>fers a set <strong>of</strong> primary data that willbe continually reassessed and mined for informationwith each new archaeological discovery<strong>of</strong> the future.In summary, the Belitung ship is one amonga growing number <strong>of</strong> maritime sites found inSoutheast Asia and it is presently the oldest ina chronological list <strong>of</strong> ships with trade ceramics.The Belitung belongs to the earliest <strong>of</strong> three primarygroups <strong>of</strong> sites: the group, which presentlyincludes remains from the third to thirteenth<strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shipwreck</strong> <strong>Excavation</strong> in Southeast Asia 55