'Only a footstep away' - Skills for Care - Think Local Act Personal

'Only a footstep away' - Skills for Care - Think Local Act Personal

'Only a footstep away' - Skills for Care - Think Local Act Personal

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

we identifynew andinnovativeways ofworking‘only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’?:neighbourhoods, social capital & their place in the‘big society’a skills <strong>for</strong> care work<strong>for</strong>ce development background paperjune 2010

prefaceWelcome to Only a Footstep Away, <strong>Skills</strong><strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>’s first published venture into thefields of community development and‘neighbourhoodism’. This is going to be anincreasingly important area <strong>for</strong> adult socialcare, extending the range of cross-sectorperspectives that we address under theheading of ‘new types of worker and new waysof working.’In 2008 we published the Principles ofWork<strong>for</strong>ce Redesign, in which the seventhprinciple highlighted the importance ofunderstanding your local community. Since thepublication of the principles, the importanceof understanding your local community orneighbourhood has been rein<strong>for</strong>ced by a rangeof publications from the new types of workerprojects that we support. Some of these are onwww.newtypesofworker.co.uk.In those projects it has become clear that<strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> needed, in the context ofpersonalisation, to explore the skills andskill requirements of those who would notnecessarily see themselves as part of the socialcare work<strong>for</strong>ce, but who do have an importantpart to play in enabling people to continue tolive in their neighbourhoods.This report examines the literature thatsupports the development of a community skillsapproach where, through a careful analysis ofthe skills that exist in a local neighbourhood,the right skills development can be put in placeto enable those vulnerable adults living in thatneighbourhood to experience a greater level ofsupport and independence.Only a Footstep Away is an important grounding<strong>for</strong> our thinking about neighbours andneighbourhoodism. It provides <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>with a strong starting point from which to pilotthe concepts of community skill developmentand neighbourhood leadership development.From here we can go on to create the analyticalskills assessment framework from which we willcreate a strategic approach to community andneighbourhood skills development.We know that we do not have to start fromscratch. <strong>Local</strong> government and the voluntarysector have well-established neighbourhooddevelopment expertise <strong>for</strong> social care to drawupon. And we know that colleagues in healthand housing already draw on that expertise.Whilst social care is already doing so too, onthe ground, it is not yet doing so in the strategicplanned way that is necessary to make bestuse of existing skills and to be systematic aboutaddressing skills gaps.We also know that the time is right politicallyto address community and neighbourhoodapproaches. Only a Footstep Away refers tothe coalition government agreement, publishedas this work was being finalised, which makesreference to the need <strong>for</strong> greater respect <strong>for</strong>,and involvement of local communities in work toimprove people’s lives.These perspectives now need to be combinedwith our learning from the new types of workerprogramme, plus the principles of work<strong>for</strong>ceredesign, to create a practical work<strong>for</strong>cestrategy to boost social care’s neighbourhoodeffectiveness. This will be an importantchallenge <strong>for</strong> <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> over the next threeyears, and we are keen to involve social care’sother leaders in the work.Professor David Croisdale-Appleby OBEIndependent Chair, <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>For more in<strong>for</strong>mation on this project, pleasecontact Jim Thomas, Programme Head, <strong>Skills</strong><strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>, jim.thomas@skills<strong>for</strong>care.org.uk

acknowledgementsThis paper was commissioned by <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> from independent consultants Bob Hudsonand Melanie Henwood. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors, and notnecessarily those of <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>. The authors are grateful to Jim Thomas <strong>for</strong> his supportand helpful comments throughout.‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? Neighbourhoods, social capital & their place in the ‘big society’Published by <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>, West Gate, 6 Grace Street, Leeds LS1 2RP www.skills<strong>for</strong>care.org.uk© <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> 2010Copies of this work may be made <strong>for</strong> non-commercial distribution to aid social care work<strong>for</strong>ce development. Any othercopying requires the permission of <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>.<strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> is the employer-led strategic body <strong>for</strong> work<strong>for</strong>ce development in social care <strong>for</strong> adults in England. It is partof the sector skills council, <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> and Development.This work was researched and written by Bob Hudson and Melanie Henwood, working to a commission from <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong><strong>Care</strong>.Bibliographic reference data <strong>for</strong> Harvard-style author/date referencing system:Short reference: <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> [or SfC] 2010Long reference: <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>, ‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? Neighbourhoods, social capital & their place in the ‘Big Society’,(Leeds, 2010) www.skills<strong>for</strong>care.org.uk<strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> would like to acknowledge the assistance of Bob Hudson and Melanie Henwood in the development ofthis work.

contentsExecutive summaryi1 Introduction 12 What do we mean by 'neighbourhood'? 43 What do we know about neighbourliness? 6Proximity 6Timeliness 6Physical environment 6Length of residence 7Social polarisation 7<strong>Personal</strong> circumstances 7Normative assumptions about neighbouring 8The nature and role of social capital 94 Neighbourhood policy and practice 11National government programmes 12National non-statutory sector programmes 15Time banks 16Pledgebanks 16Lifetime neighbourhoods 17<strong>Local</strong> programmes 18<strong>Local</strong> Area Coordination (LAC) 18Connected <strong>Care</strong> 18Derby Neighbourhood and Social <strong>Care</strong> Strategy 19Sheffield Community Portraits 19Southwark Circle 20The Asset Approach 205 Work<strong>for</strong>ce implications 21Neighbourhood napping and data analysis 21Community engagement and involvement 23Developing neighbourhood leaders 26In<strong>for</strong>mal neighbourhood leaders 26Formal neighbourhood leaders 266 Conclusions & next steps 28References 32

executive summary1. This paper is a background discussiondocument produced <strong>for</strong> <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong>. Itscopes the meaning and understanding ofneighbours and neighbourhoods andconsiders how this might in<strong>for</strong>m strategicdevelopment on neighbourhood work<strong>for</strong>ceplanning and skills development. The paperalso locates the discussion within thecontext of the emerging debate around themeaning of social capital, the concept of the‘Big Society’ and empowerment of peopleand communities as a plat<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> thedelivery of fairness and opportunity.2. We have explored the literature acrossa range of disciplines to consider thetheoretical, conceptual and empiricalunderstandings of ‘neighbourhood’. Wehave not confined our analysis to in<strong>for</strong>maland voluntary care between neighbours (i.e.care by the neighbourhood), but have alsolooked at the scope <strong>for</strong> services andsupport to be configured on aneighbourhood basis (care in theneighbourhood). As well as broadening thefocus to encompass <strong>for</strong>mal, semi-<strong>for</strong>maland in<strong>for</strong>mal sources of support, we havealso moved beyond social care to considerthe wider health and well-being agenda.3. It is evident that there is considerableambiguity and lack of consensus in themeaning and understanding of terms suchas ‘neighbour’ and ‘neighbourhood’. Somedefinitions concentrate on spatial andgeographical boundaries, and otherobjective measures. However, people’s ownunderstanding of their neighbourhood istypically expressed in terms of socialnetworks and relationships.4. Neighbouring can be understood interms of a continuum which ranges frompractical activity through to emotionalsupport; or from latent to manifestneighbourliness. We identify the themes thatrecur as factors which shape theneighbourhood experience. These include:proximity; timeliness; physical environment;length of residence; social polarisation, andpersonal circumstances.5. It would be unwise to equate theconcept of neighbourhood with emotionaland normative assumptions about thecapacity of the neighbourhood to act as arich source of ‘social capital’. Theincreasingly popular notion of social capitalis often poorly defined and used in nonspecificways. A recent review of theliterature in this area identified eight keydimensions of social capital in terms of:family ties; friendship ties; participation inlocal organised groups; integration into thewider community; trust; attachment to theneighbourhood; tolerance; being able to relyon others <strong>for</strong> practical help. Others havedistinguished between social capital as‘bonding capital’ (networks withincommunities), and ‘bridging capital’(networks between communities).6. Some conceptualisations of socialcapital focus on the importance ofreciprocity, and the exchange of goods andservices <strong>for</strong> mutual benefit. Somecommentators have suggested that arequirement <strong>for</strong> all citizens to contribute agiven number of hours of voluntary work in ayear or over a lifetime might be a fruitful wayof developing a culture in which reciprocityis the norm and where transactions can beused to meet practical needs such assupporting older relatives. While suchpositions are likely to be controversial, somepoliticians are eager to adopt at leastelements of this model.7. Much of the focus of neighbourhoodpolicy development over the past decade orso has been concerned with strategies thatattempt to integrate bonding and bridging‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? i

capital by encouraging the emergence oflocally generated initiatives in place of topdownimplementation. We explore a numberof these neighbourhood-focused initiativesand programmes at the levels of nationalgovernment programmes; national nonstatutorysector programmes, and locallygenerated programmes.8. In addition to understanding ideasabout neighbourhoods andneighbourhoodism, any approach toneighbourhood work<strong>for</strong>ce development alsorequires a clear understanding of the needsthat any work<strong>for</strong>ce is intended to address.This is the objective of neighbourhoodmapping and analysis. There has beensignificant improvement in the availability oflocalised data presented as ‘Super OutputAreas’. This includes, <strong>for</strong> example, morbidityand mortality in<strong>for</strong>mation; crime andcommunity safety data; community wellbeingin<strong>for</strong>mation; housing data on tenureand conditions; and economic deprivationdata. However, it is understood that thequality and sophistication of this level ofdata is currently limited, as is local analyticcapacity.9. The notion of community ‘capacitybuilding’ appears regularly in official policydiscourse. The characteristics of communitycapacity have been identified as: a sense ofcommunity; level of commitment amongcommunity members; problem-solvingmechanisms; and access to resources.There is evidence that light touch support,mentoring and some resource availabilitycan indeed foster the building of capacity.The role of neighbourhood leaders as partof capacity building is an area that has beenrelatively neglected.neighbourhood literatures in sociology,social policy and public policy our concernhas been to ensure that further work<strong>for</strong>cedevelopment at this level will be evidencebased.We highlight a number of issues thatany work<strong>for</strong>ce strategy will need to address,including recognition that: this is a complexterritory that crosses many dimensions oflife within any community; <strong>for</strong>mal andin<strong>for</strong>mal aspects will need to be integratedand mutually supporting; core skills need tobe identified and developed, and thecapacity to develop and support socialcapital must be better understood.11. The trans<strong>for</strong>mation agenda of PuttingPeople First (DH 2007) established by thelast government requires local action acrossthe four inter-related dimensions of:universal services; early intervention andprevention; choice and control, and socialcapital. The way in which the last of thesehas been expressed suggests a relativelylimited understanding of the concept andlack of clarity about how it should be taken<strong>for</strong>ward at local level. There is considerablework to be done in ensuring that the lessonsand understandings of several decades’experience in neighbourhoods,neighbourhoodism, co-production, etc.,in<strong>for</strong>m local and national developments. Ourreview of the key literature is a step towardssupporting this learning, and ensuring thatemergent work<strong>for</strong>ce strategies are based inreality and not on naively optimistic viewsabout the nature of communities,neighbourhoods and reciprocity. There areopportunities to build on the increasedattention being directed to neighbourhoods;it is vital that this is approached in ways thattranscend party politics and short-termpopulism.10. Our analysis of the literature does notat this stage provide a preliminaryneighbourhood work<strong>for</strong>ce developmentstrategy. However, it is a prelude to anysuch development. In drawing lessons from‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? ii

1 introduction1.1 This report is a background paperproduced <strong>for</strong> <strong>Skills</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Care</strong> as a prelude tofurther work on developing a strategy onneighbourhood work<strong>for</strong>ce planning andskills development. The work has beencommissioned from independentconsultants Professor Bob Hudson andMelanie Henwood. Since the work wascommissioned in early 2010, its focus hasbecome of greater significance. As weexplore below, ideas of community andneighbourhood are increasingly central topolitical discourse, and we trust that thispaper will be a helpful contribution to thegrowing debate about the meaning of the‘big society’, the development of socialcapital and the implications <strong>for</strong> work<strong>for</strong>cedevelopment.1.2 The aim behind the paper is toconsider the substantial literature on‘neighbourhood’ – theoretical, conceptualand empirical – and to outline currentpolicies that focus upon ‘theneighbourhood’. By doing so it should befeasible to anchor subsequent work<strong>for</strong>cedevelopment proposals within a robustevidence base. Our stance is thatexploration should not be confined toexamining in<strong>for</strong>mal and voluntary careamongst neighbours (i.e. care by theneighbourhood), but should alsoencompass the scope <strong>for</strong> wider servicesand support to be neighbourhoodconfigured(care in the neighbourhood). Inthis way we can begin to think morecreatively about <strong>for</strong>mal, semi-<strong>for</strong>mal andin<strong>for</strong>mal sources of support, and lookbeyond social care to the wider health andwellbeing agenda. This should also makethe report of interest to other skillscouncils.1.3 Almost everyone has neighbours, yetthe neighbourhood is a relatively neglectedlevel of analysis - the bulk of academic andpolicy attention has focused upon thelevels above the neighbourhood (thepolitical, economic and value systems ofsociety as a whole) or beneath it (interpersonalrelationships in settings such asthe family). However, neighbourhoodsderive significance from their proximatestatus as compared with the remotenessof other systems of governance,production or consumption—neighbourhoods do matter <strong>for</strong> the peoplewho live in them.1.4 Evidence suggests that thedifferences between neighbourhoods interms of institutional resources, patterns ofsocial organisation and networks, levels ofcommunity safety, quality of the physicalenvironment and levels of trust, eithersupport or undermine how people are ableto overcome difficulties and developresilience (Pierson 2008). We also knowthat people living within the same areaoften share similar mental and physicalstates of health, as assessed by indices ofneighbourhood deprivation, so targetingsupport in these areas seems to makesense (Blackman 2006), and that thequalities of the surroundings in which welive are among the main concerns aboutquality of life that are reported in surveys ofUK residents (MORI 2002).1.5 The importance of theneighbourhood in people’s lives has slowlygained a foothold in policy visions, notablyas a key aspect of the last government’sSocial Exclusion Strategy (SEU 2000,2001). This suggested a number ofpossible strands to neighbourhoodrenewal, including jobs and training,reducing crime and anti-social behaviour,provision of better community facilities,tackling problems of neglected andabandoned housing, rebuilding communitysupport and providing greater assistance‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 1

to schools and young people. In 2005 the<strong>for</strong>mer Office of the Deputy Prime Ministerpublished Why Neighbourhoods Matter(ODPM 2005) which identified several waysin which neighbourhood level activity canbe socially beneficial. Such activity, it wasargued, can:• make a real difference to the qualityand responsiveness of services thatare delivered to or affect thoseneighbourhoods• increase the involvement of thecommunity in the making ofdecisions on the provision of thoseservices and on the life of theneighbourhood• provide opportunities <strong>for</strong> publicservice providers and voluntary andcommunity groups to work togetherto deliver outcomes <strong>for</strong> the locality• build social capital—reducingisolation whilst building communitycapacity and cohesion.1.6 Indeed the neighbourhood questionhas now spread beyond specific policyinitiatives to become a key part of thewider ideological debate about finding theright balance between central governmentand ‘localism’. It was reported, <strong>for</strong>example, that the Labour Party wasconsidering a manifesto pledge to turnschools and hospitals into ‘mutualised coops’where staff and local people have areal stake in service improvement. In theevent, the Labour manifesto (Labour 2010)took a softer line with a commitment topromoting social enterprises, including aright <strong>for</strong> public sector workers to requestthat front line services be delivered througha social enterprise. The manifesto alsoacknowledged ‘the new mutualism’reflected in “growing interest in cooperativeand mutual organisations thatpeople trust, and that have the capacity tounleash creativity and innovation, creating‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 2new jobs and services – particularly indisadvantaged neighbourhoods wheretraditional approaches have failed in thepast.” (Labour 2010, 7:5)1.7 The Conservative Party has placedemphasis upon encouraging families,charities and communities to cometogether to solve problems (Guardian2009), and their election manifestohighlighted the ambition <strong>for</strong> “every adultcitizen being a member of an activeneighbourhood group,” and outlined plansto introduce a National Citizen Service <strong>for</strong>16 year olds “to help bring our countrytogether” (Conservative 2010). Morebroadly, this manifesto expressed anaspiration to build the ‘big society’, “to helpstimulate social action, helping socialenterprises to deliver public services andtraining new community organisers.” Thecentral theme of the manifesto wasempowering individuals and communitiesto take greater local control, and in doingso the Conservatives were clearly movinginto territory that has traditionally beenmore closely associated with the LabourParty.1.8 The Liberal Democrat manifestosimilarly stated a commitment “to handingpower back to local communities. Webelieve that society is strengthened bycommunities coming together andengaging in voluntary activity, which setspeople and neighbourhoods free to tacklelocal problems.” (LD 2010)building the ‘big society’1.9 The outcome of the General Electionin May 2010 resulted in a hung parliamentand subsequently to the establishment of acoalition government between theConservatives and the Liberal Democrats.The initial coalition agreement documentset out 11 key issues that needed to beresolved “in order <strong>for</strong> us to work togetheras a strong and stable government" (Con

LD 2010). The agreement was intended asa plat<strong>for</strong>m on which other elements wereto build. The first of these to be published(on 18 May) addressed the ‘big society’,and the new Prime Minister described thisas “a big signal” about the importanceattached to the issues of decentralisingpower and empowering communities. The“driving ambition” of the coalitiongovernment is stated as being “to putmore power and opportunity into people’shands” (HMG 2010a) The statement on thebig society went on to highlight the need to“draw on the skills and expertise of peopleacross the country as we respond to thesocial, political and economic challengesBritain faces.” Five key areas of agreementwere set out:• give communities more powers• encourage people to take an activerole in their communities• transfer power from central to localgovernment• support co-ops, mutuals, charitiesand social enterprises• publish government data.1.10 Volunteering and involvement insocial action are to be encouraged, andthe idea of a National Citizen Service thatwas set out in the Conservative manifestois to be taken <strong>for</strong>ward, initially in aprogramme <strong>for</strong> 16 year olds “to give thema chance to develop the skills needed tobe active and responsible citizens, mix withpeople from different backgrounds, andstart getting involved in their communities.”In supporting communities to do more <strong>for</strong>themselves and each other, and toestablish neighbourhood groups acrossthe UK, a new generation of communityorganisers is to be trained. (HMG 2010b)1.11 Mutuals, co-operatives, charities andsocial enterprises are to be supported andto have greater involvement in the running‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 3of public services. Funds from dormantbank accounts will be used to establish a‘Big Society Bank’ to ”provide new finance<strong>for</strong> neighbourhood groups, charities, socialenterprise and other non-governmentalbodies.”1.12 In launching the idea of the bigsociety the Prime Minister acknowledgedthe financial situation and the difficultchoices facing government spending, andstated that he did not “have some naivebelief that the Big Society just springs up inits place.” Rather, the agenda <strong>for</strong>government needed to be how to enablethe third sector to “do even more of whatyou do.” The PM went on to say that hewanted this work “to be one of the greatlegacies of this government: building theBig Society.” (PM 2010)1.13 The new Deputy PM, Nick Clegg,also endorsed the approach and arguedthat the parties had been using differentwords <strong>for</strong> a long time but meaning thesame thing in terms of liberalism,empowerment and responsibility. Thechallenge would be to bring about “a hugecultural shift, where people, in theireveryday lives, in their communities, in theirhomes, on their street, don’t always turn toanswers from officialdom, from localauthorities, from government, but that theyfeel both free and empowered to helpthemselves and help their owncommunities.” (DPM 2010)1.14 Ideas of neighbourhood andcommunity are clearly of growing politicalimportance, and it is evident that thesethemes will be major components of thepolicy agenda <strong>for</strong> the new coalitionadministration (HMG 2010b). However, torecognise the significance ofneighbourhood is only the starting point inunderstanding a complex and contestedconcept, along with its associated policydevelopments. In this report our approach

is to undertake four sequential stages ofexploration:• What do we mean by the concept of‘neighbourhood’?• The evidence base: what do weknow about the determinants ofgood neighbouring?• Neighbourhood policy and practicein England: building on existingdevelopments.• Broad work<strong>for</strong>ce implications andproposals <strong>for</strong> next steps work.2 what do we mean by‘neighbourhood’?2.1 There is considerable ambiguity inthe meaning and use of terms like‘neighbour’ and ‘neighbourhood’. In thelandmark study published in 1986, Abramsclaimed that “the literature is scant,predominantly atheoretical and notsufficiently advanced to have produced adebate on concepts, let alone aconsensus” (Bulmer 1986, 17). Althoughthere have been subsequentimprovements, the claim still has validity.2.2 All studies agree that proximity is anessential attribute of a neighbourhood, withmuch agreement that neighbours livewithin walking distance and that face-tofacecontact is possible. Models ofcommunity mapping, or populationprofiling, use such an approach. Forexample, Mosaic is a methodology thatclassifies UK postcodes against more than400 socio-demographic variables.Residents within a specific postcode areaare more likely to reflect the characteristicsof that group than of another. However,some definitions assume that aneighbourhood can be rigidly defined witha set of boundaries, neglecting the realitythat the local residential environment isdefined by a wide range of attributes, eachof which will have its own spatialboundaries. Definitions may range from afew street blocks close to people’s homes,to the wider district where local civicamenities can be accessed, or on thebasis of local electoral ward boundaries.This means that the spatial extent of aneighbourhood may be defined differentlyby residents and service providersrespectively – a conflict between subjectiveand objective maps of locality. Thus whileneighbourhoods may be definedgeographically <strong>for</strong> some purposes, themeaning of neighbourhoods is generallyunderstood in terms of social networksand relationships.2.3 A second common feature is thatthe neighbourhood relationship is relativelylimited and indeterminate – it is framed by‘being nearby’ and in general terms by littleelse. Some classic network studiessupport the assertion of the importance oflocation and neighbourhood, pointing tothe close association between densenetwork <strong>for</strong>ms and local neighbourhood.However, in his review of the evidence onneighbourhoods and social networks,Bridge concludes that:“It is only in the working class that one islikely to find a combination of factors alloperating together to produce a highdegree of density: concentration of peopleof the same or similar occupations in thelocal area; jobs and homes in the samelocal area; low population turnover andcontinuity of relationships; at leastoccasional opportunities <strong>for</strong> relatives andfriends to help one another to get jobs;little demand <strong>for</strong> physical mobility; littleopportunity <strong>for</strong> social mobility.” (Bridge2002, 10)2.4 Where these factors are not presentthen a problematic juncture betweenneighbourliness and privacy is evident.‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 4

Abrams notes that the placing of respect<strong>for</strong> privacy on the same footing asfriendliness and helpfulness occurs inalmost all studies, yet “the precise point atwhich one might distinguish friendlinessfrom mere civility at one extreme or a deepconcern at the other remains highlyobscure.” (Bulmer 1986, 28) Thus goodneighbouring may be as much aboutshowing restraint, non-involvement andlatent qualities, as it is about activities thatsocial scientists can observe and record.2.5 A common conceptual interchangeis that between ‘neighbourhood’ and‘community’, with both being perceived as‘in decline’. Much of the classic literatureon neighbourhoods and networks is part ofwhat is called the urbanisation literaturethat discusses the consequences of thegrowth of the industrial city in westernnations. Even in the nineteenth century thesociologist Tonnies argued that in ruralgemeinschaft (or community) social orderwas based on multi-stranded social ties.People knew each other in a range ofroles—as parents, neighbours, co-workers,friends or kin. In contrast, residents ofurban neighbourhoods lived in a gesellchaft(or association) with single-stranded ties—only knowing each other in single,specialised roles such as neighbours.(Tonnies 1887)2.6 Arguments about the decline ofcommunity are in large measure argumentsabout an unavoidable decline in the densityof local social networks (orneighbourhoods). High density hasgenerally been associated with solidarity,commitment and normative consensus,whereas low density is held to bring aboutall sorts of contrary conditions. It is throughthe erosion of density that modernisationand urbanisation are said to haveweakened traditional social solidarities,including those of caring neighbourhoods.2.7 However, as Abrams has argued,these ‘natural’ helping networks of thetraditional neighbourhood were in fact away of life worked out to permit survival inthe face of great hardship—“conditionswhich one would not wish to seereproduced today” (Bulmer 1986, 92).Most neighbourhoods today do notconstrain their inhabitants into stronglybonded relationships with one another.Better transport, longer journeys to work,geographical dispersal of kin and friends, awider range of shopping and recreationalopportunities, and the privatisation of thefamily, have all reduced the centrality of theneighbourhood as a locus of socialinteraction and social support. It is in thesechanged circumstances that calls torecreate civic values and shared activitiesstruggle to make an impact, <strong>for</strong> the currentpolicy imperatives seem to be at odds withthese dominant social trends.2.8 Given all of this, it makes sense tothink in terms of a continuum of differenttypes of neighbouring rather than somehomogeneous concept which is eitherpresent or absent. One can distinguish, <strong>for</strong>example, between practical activity (suchas taking in a parcel or feeding theneighbour’s cat) and emotional supportsuch as looking to neighbours in time ofcrisis (Bridge 2004). Mann usefullydistinguished between manifest and latentneighbourliness. Manifest neighbourlinessis characterised by overt <strong>for</strong>ms of socialrelationships such as mutual visiting in thehome and going out <strong>for</strong> leisure andrecreation. Latent neighbourliness ischaracterised by favourable attitudes toneighbours which result in positive actionwhen a need arises in times of emergencyor crisis. (Mann 1954) Feelings of wellbeingvia neighbouring may have as muchto do with this latent potential as theactivities routinely identified inneighbourhood studies.‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 5

2.9 A helpful conceptual framework isproposed by Abrams, who makes thefollowing distinctions (Bulmer 1986, 21):• neighbours are simply people wholive near one another• neighbourhood is an effectivelydefined terrain inhabited byneighbours• neighbouring is the actual pattern ofinteraction observed within any givenneighbourhood• neighbourliness is a positive andcommitted relationship constructedbetween neighbours as a <strong>for</strong>m offriendship.2.10 The latter concept is critical to muchcurrent policy and political discourse, andrequires an answer to the question, ‘Whatare the determinants of neighbourliness?’This is the focus of the following section.3 what do we knowabout neighbourliness?3.1 There is a substantial researchliterature going back over at least eightyyears that has attempted to identify thefactors that shape the neighbourhoodexperience. Several themes recur.proximity3.2 Although sounding like a truism,proximity is a key factor in shapingneighbourhood experiences. The studiesundertaken as part of the Abrams research(Bulmer 1986) found that the mostfrequently mentioned influence on whetheror not neighbourly relations developed wasproximity – being next door to someone isdifferent from living in the next street tothem. Proximity is also related to thepreviously noted importance of the ‘watchand ward’ function in times of crisis andemergency. Blackman (remarks that whilstthe neighbourhood unequivocally starts aswe leave our front door, where it ends willvary according to many spatial andtemporal factors, but the concept of a‘walkable zone’ remains important. Henotes that:“People endow a neighbourhood withorganisation through their walking patternsfrom the nodal points of their homes—walking children to school, walking to thebus stop or local shops, and walking to callon neighbours... but the extent to which aneighbourhood emerges empiricallydepends on whether local interactionscreate common attributes bounded bygroup properties.” (Blackman 2006, 33)timeliness3.3 Speed of response is a furtherspecial province of neighbours, rangingfrom the quick convenience of ad hocborrowing and lending, to help in anemergency when time is of the essence.However, the availability of time toparticipate in neighbouring is one of thefactors associated with the ‘loss ofcommunity’. Even in the researchundertaken in the 1980s, Abrams (Bulmer1986) found the observation by people that‘neighbouring is not what it used to be’being explained in terms of the availabilityof time. The increase in femaleemployment was an especially notedfactor. In his examination of semi-<strong>for</strong>malGood Neighbour schemes, he found thatthe crucial attribute that determinedinvolvement was whether or not peoplehad time to spare.physical environment3.4 Inside the home – whether it isdamp, cold, noisy or overcrowded – sitswithin the wider neighbourhood context ofwhich it is a part. As Blackman puts it,“housing is experienced as the dwellingand its residential setting, the‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 6

neighbourhood.” (Blackman 2006, 25) Theofficial definition of a ‘poor neighbourhood’is that used in the English House ConditionSurvey which is based on a neighbourhoodhaving over 10% of its dwellings assessedas seriously defective. Using this measure,around 10% of the national housing stockwas classed in ‘poor neighbourhoods’ in2001.3.5 There is also some evidence tosuggest that the physical layout of both thehouse and the neighbourhood can shapelevels of neighbourly activity. Brown andBurton (1998), <strong>for</strong> example, demonstrated(in the USA) the significance of the frontporch as a semi-public space in whichnon-threatening and non-intrusiveneighbourly relations could be initiated andreproduced. And the Abrams studies(Bulmer 1986) found that the segregationof elderly people in bungalows and flats cutthem off from neighbours other thanpeople of their own age, and that thisaccentuated social isolation.length of residence3.6 The Abrams studies concluded thatthe most obvious factor accounting <strong>for</strong>variations in neighbouring was the longevityof the settlement and the length ofresidence there of particular households.Clear differences were observed betweenlong-time residents and newcomers interms of contact with neighbours and thesort of help exchanged. This is partlyexplicable in terms of exchange theory. Inthe modern neighbourhood milieu,exchange relations will typically evolve as aslow process, starting with minortransactions in which little trust is requiredbecause little risk is involved. Only whenmutual trust is more firmly established willthere be a gradual expansion of mutualsupport.3.7 This picture is supported by moreextensive longitudinal studies. Wenger andher colleagues analysed data on lonelinessamong older people from the BangorLongitudinal Study of Ageing. (Wenger1996). They reported that the mostsuccessful network in terms of avoidingloneliness and isolation was the ‘locallyintegrated support network’, which wasusually based upon long-term residence. Inanother paper based upon the same datathe authors further noted that people insuch networks were less likely to needstatutory services to help with personalcare. (Wenger 2001)social polarisation‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 73.8 Reciprocal care between neighboursgrows where in<strong>for</strong>mation and trust arehigh, and where resources <strong>for</strong> satisfyingneeds in other ways are low. This is mostlikely to occur in relatively isolated,relatively closed and relatively threatenedsocial milieu with highly homogeneouspopulations. This could be part of a viciouscircle of decline as qualitatively better jobsand homes elsewhere will be in reach of atleast some of the residents, and theirdeparture further deepens themarginalisation of those remaining. Dorlingand Rees (2003) note that with continuingsocio-spatial polarisation, areas are nowmore easily typified as being old andyoung, settled and migrant, black andwhite or rich and poor. Indeed, in theirstudy of young people growing up indepressed parts of Teesside, Macdonaldand Marsh (2005) found that most choseto remain living in very deprivedneighbourhoods, seeing these as ‘normal’.<strong>Local</strong> social divisions were perceivedinstead at a very fine-grained scale such asstreets or parts of an estate withtroublesome residents.personal circumstances3.9 Abrams found that apart fromproximity, the most salient influencesmentioned as promoting neighbourliness

were age and status in the life cycle. Heargued that most neighbours do nottypically choose to make their friendsamong their neighbours, and that thosewho do tend to be seeking highly specificsolutions to highly specific problems.Bridge (2002) describes this situation as‘residual neighbouring’ <strong>for</strong> people who donot have access to broader networks. Themost relevant group <strong>for</strong> the purposes ofthis paper is older people, <strong>for</strong> the degree ofsocial exclusion they experience is closelyrelated to the places they live.3.10 Pierson (2008) points out that olderpeople are especially susceptible to theoccurrence of major life events that paredown relationships and networks—losing apartner, adjusting to living alone, the loss ofclose family members and friends,withdrawal from the labour market, and theonset of chronic illness and disability. TheSocial Exclusion Unit’s report on theexclusion of older people in disadvantagedneighbourhoods demonstrated the extentto which older people ‘age in place’, andare there<strong>for</strong>e especially vulnerable tochanges in the character of theneighbourhood. (SEU 2005)3.11 The most commonly experienced<strong>for</strong>m of social exclusion was found to be‘social relations’, which included suchfactors as isolation and loneliness, and lackof participation in everyday social activities.Both isolation and loneliness areassociated with poor health and withdiminishing contact with healthprofessionals, as well as with higheradmission to residential care, depressionand poor recovery from strokes. However,Wenger (2001) also points out that manyolder people who live alone (and are hencetechnically ‘isolated’) do lead socially activelives and have close friendships that aremore important than thinning family ties. Sopeople who are isolated do live alone, butthe reverse is not necessarily true.normative assumptions aboutneighbouring3.12 It is already clear from the keymessages about neighbouring that it isunwise to equate the concept ofneighbourhood with emotional andnormative assumptions about the capacityof the neighbourhood to act as a richsource of ‘social capital’. Even in the1980s, Abrams was complaining that“much of the appeal of the call <strong>for</strong>neighbourhood care has been a matter ofill-defined sentiment and impreciserhetorical resonance” (Bulmer 1986, 23)and this is true today in the way theconcept of ‘social capital’ is sometimesused. The recent DCLG publication‘Building Cohesive Communities’, <strong>for</strong>example, identifies the followingdimensions of ‘commitment to a sharedfuture’:• wanting to live in the area• using local services, shops, schoolsand businesses• investing in local social capital suchas volunteering, attendingneighbourhood <strong>for</strong>ums and beinglocal leaders• feeling safe and having contact withneighbours• having a sense of their own powerto be involved and to influence• understanding and welcoming therange of different people in the area• developing a local identity focusingon shared local experiences. (DCLG2009a)3.13 What is less clear is how all of thiscan be brought about, including thepotential role of a neighbourhood focusedwork<strong>for</strong>ce strategy. On the contrary, somehave used the term ‘the geography ofmisery’ (Burrows & Rhodes 1998) to‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 8

describe certain disadvantaged areas inwhich neighbourhood ties may not besuperior ties. Some commentators havebroadened the issue further to attribute theresponsibility <strong>for</strong> urban disadvantage uponan ‘underclass’ whose members makepoor moral choices. (Murray 1994) And inan influential contribution, Wilson andKelling (1982) proposed their ‘brokenwindows’ theory whereby disorganisationand a lack of in<strong>for</strong>mal social control lead toa spiral of neighbourhood decline as socialand physical incivilities go unchallengedand exponentially increase, furtherreducing civic interaction. The policingstrategy of ‘zero tolerance’ is a response tothis theory.3.14 There is little doubt that significantproportions of people do have concernsabout aspects of their local area. Marketresearch from MORI (2002) and other localsurveys has <strong>for</strong> several years beenreporting that the most prominent issues<strong>for</strong> many residents are about local crimeand anti-social behaviour, dirty streets andneglected spaces and lighting. The 2008Place Survey conducted by DCLG, <strong>for</strong>example, found:• 31% felt there was a problem withpeople not treating one another withrespect and consideration• only 30% felt that parents in theirlocal area took responsibility <strong>for</strong> thebehaviour of their children• 20% felt that anti-social behaviourwas a problem in their local area• around a quarter felt drunk or rowdybehaviour and drug use or drugdealing were problems in their localareas. (DCLG 2008)3.15 Other research has highlightedspecific problems of targeted violence andhostility towards disabled people. A recentstudy undertaken <strong>for</strong> the Equality andHuman Rights Commission by Sin (2009)found the fear and experience of a widerange of criminal, sub-criminal and antisocialbehaviour to be having a markedimpact on the social inclusion andwellbeing of people with learningdisabilities. ‘On the street’ near to wherethe victim lived was found to be one ofseveral hostility ‘hot spots’. These findingsconfirm those of an earlier study by the UKDisabled People Council (UKDPC 2007).The consequences can be tragic as hasbeen seen recently with the Pilkingtoncase, where a vulnerable single motherkilled herself and her severely disableddaughter after years of unchecked ‘lowlevel’ abuse from local youths. Suchrealities are of enormous importance giventhe ambitions of the trans<strong>for</strong>mation agendain social care to promote personalisation ofcare and support, much of which ispredicated on people being supported touse mainstream services and to live in localcommunities rather than in segregatedhousing.the nature and role of social capital3.16 The idea that the neighbourhoodfosters the development of supportivesocial networks through interaction in localpublic space is clearly far fromstraight<strong>for</strong>ward, and it is against thisbackground that the role of theincreasingly popular notion of ‘socialcapital’ has to be considered. The term isone that is widely used but often poorlydefined, leading to confusion andmisunderstanding. A review of the literatureundertaken <strong>for</strong> the ONS observed:“This has been exacerbated by thedifferent words used to refer to the term.These range from social energy,community spirit, social bonds, civic virtue,community networks, social ozone,extended friendships, community life,social resources, in<strong>for</strong>mal and <strong>for</strong>mal‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 9

networks, good neighbourliness and socialglue.” (ONS 2001)3.17 The concept has becomeparticularly associated with the writing ofRobert Putman who defines it as ‘thefeatures of social organisation such asnetworks, norms and social trust thatfacilitate coordination and cooperation <strong>for</strong>mutual benefit’ (Putman 1995, 67). Areview of the literature on social cohesionand social capital by Staf<strong>for</strong>d (2005)identified eight dimensions:• family ties• friendship ties• participation in local organisedgroups• integration into the wider community• trust• attachment to neighbourhood• tolerance• being able to rely on others <strong>for</strong>practical help.3.18 The neighbourhood may be onesource of social capital but many peopleare less dependent on neighbours <strong>for</strong>social support, and their networks are lesslocally based than in the past (and likely tobecome even less so with the dispersal ofpopulations but also because of theincreasing significance of virtual socialnetworks via sites such as Facebook). Intheir analysis of data contained in theGeneral Household Survey, Bridge andothers (2004) report that visits toneighbours took place on at least three orfour days per week by almost 50% ofrespondents, but there is no additionaldata on the nature and extent of suchvisits. Similarly the 2008 Place Surveyfound that 23% of respondents said theyhad given unpaid help (excluding donatingmoney) in a voluntary capacity during theprevious twelve months. (ONS 2008)3.19 Another approach to understandingsocial capital is what David Halpern terms‘the hidden wealth of nations’. This refersto a parallel world of relationships andreciprocal interactions that ‘makes oursocieties and economies work.’ (Halpern2010, 2) In particular, ‘the economy ofregard’ includes “the myriad of ways inwhich people help, show affection, care <strong>for</strong>and support each other in everyday life.”(p.98) Within this economy, the relationshipbetween the giver and receiver is a keyfeature. Halpern poses questions aboutwhether and how the economy of regardcan be supported and encouraged,including approaches that make mutualsupport and voluntary activity anexpectation within society. We will return tothis later in the paper.3.20 All these findings do at least suggestthere is some basis <strong>for</strong> developing localstrategies on social capital, and thebenefits of doing so have been muchrehearsed. Putman (1995) argues thatsocial capital has a strong influence onhealth status, and that measures of socialcapital correlate with those on morbidityand premature mortality, independently ofthe effects of material deprivation. Morebroadly he suggests that communitieswhere trust, reciprocity and socialnetworks are strong will yield collectiveaction and cooperation to the benefit ofthe wider community. It is this latter featurethat signifies social capital as a societalrather than an individual property—a‘public good’ rather than an individualpossession. In this way we can conceive ofsocial capital as consisting of the featuresof a place (such as a neighbourhood)rather than of individuals. Central to theconcept of social capital is the view that itis a resource that can be both depletedand renewed; where people work together,the stock of social capital increases, butwhere they don’t it declines—perhapsterminally.‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 10

3.21 In this context, White (2002) notesthat social capital has come to have atleast two meanings in policy terms. Firstthere is social capital as ‘bonding capital’,meaning networks and relationships oftrust within communities. Secondly there issocial capital as ‘bridging capital’, meaningthe networks and inter-relationshipsbetween neighbourhoods, communitiesand external agencies and resources. Thisdistinction further raises the question of therelationship between the two meanings,and the extent to which it is possible <strong>for</strong>bodies such as local authorities togenerate bonding capital.3.22 Again, there are two approaches tothis relationship. One approach is to viewsocial capital as an alternative to statesupport—a way of rebuilding a perceived‘broken society’ by emphasising the virtueand value of strong mutual ties. A differentapproach is to develop a strategy thatharnesses bonding capital to bridgingcapital through a range of measuresdesigned to replace top-down approacheswith locally generated initiatives andprogrammes. There has been no shortageof such developments in past decade andthese are the subject of the followingsection of this report.3.23 The fashionable term <strong>for</strong> describingthe link between bonding and bridgingcapital is ‘coproduction’—a concept thathas arisen from the critique of traditionalservices which are thought to havesupplanted rather than strengthenedpeople’s own abilities and their socialnetworks. In this perspective, communitiescannot be built upon their deficiencies, butonly upon the mobilisation of the capacityand assets of people and place. In a reviewof the issues <strong>for</strong> the Department of Health(OPM 2009) it is suggested that aframework <strong>for</strong> analysis should encompassindividual economic capital, individualcapacity, an individual’s social networks,neighbourhood relationships andcommunity associations, and public,voluntary and commercial services andfacilities.4 neighbourhood policyand practice4.1 ‘Neighbourhood support’ is a termthat appeals to two different social policydevelopments. On the one hand it canrefer to the extent and intensity ofneighbourliness achieved in aneighbourhood; on the other it can refer tothe provision of <strong>for</strong>mal or semi-<strong>for</strong>malsupport to the inhabitants of aneighbourhood with no necessaryreference to neighbourliness at all. Theidea there<strong>for</strong>e crosses a frontier between<strong>for</strong>mally organised social action andessentially in<strong>for</strong>mal relationships.Moreover, not all of the issues affectingneighbourhoods can be addressed atneighbourhood level, there<strong>for</strong>e therelationship between neighbourhood-levelsolutions and wider area strategies is alsocrucial.4.2 Barnes (2006) makes a further usefuldistinction between interventions that arecommunity-based, and those that are atcommunity level:• Community-level interventions aimat the whole community (orneighbourhood) and primarily intend tochange that community rather than to helpspecific individuals or families within it. Theapproach is based upon the convictionthat social problems (especially thosecreated by disadvantage) are best dealtwith by ‘capacity building’ in thecommunity rather than by focusing uponindividuals with problems. This ties in withthe idea of social capital as a public goodrather than an individual possession.‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 11

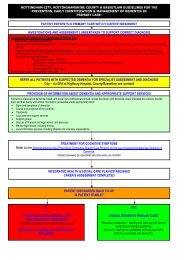

• Community-based interventionsseek to do the opposite—to meet theneeds of individuals and families throughservices and supports in the community.4.3 The position taken in this report isthat there is no reason why‘neighbourhood care’ should not bedefined in terms of pursuing bothunderstandings, though the policyemphasis has been upon improving thedelivery of public services in deprivedneighbourhoods so as to achieveimprovements in health, employment,education, housing and crime. Even withinthis approach there are differences of viewabout the appropriate scale of a‘neighbourhood’, with figures ranging fromfewer than a thousand to up to 5000households. (DCLG 2008)4.4 In addition to the ideas that theneighbourhood is potentially a valuablesource of support, a related series ofdevelopments have focused onempowering neighbourhoods in order toimprove overall well-being of residents andcommunities (Hothi 2008). In this casethere can be additional benefits that accrue– such as increased contact andinteraction between neighbours andgeneral development of social capital –without this being a specific objective of aninitiative.4.5 The rationale <strong>for</strong> neighbourhoodlevelsupport is that this will be moreaccessible and more likely to addressproblems as defined by local people.Support can be available through schools,local offices, well-known communityinstitutions or in a person’s home, and maybe delivered by professional, volunteer andin<strong>for</strong>mal personnel who know the area andits people. The past decade or so has seena large number of neighbourhood-focusedinitiatives and programmes. These mightbe categorised as national government‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 12programmes, national non-statutory sectorprogrammes and locally generatedprogrammes.national government programmes4.6 We need also to locateneighbourhood policy within a wider policycontext, and particularly that of the socialcare trans<strong>for</strong>mation agenda – PuttingPeople First – established by the previousadministration (DH 2007). The Departmentof Health has established a project aroundBuilding Community Capacity (DHCN)focused on exploring the role of socialcapital and co-production in thetrans<strong>for</strong>mation of adult social care, whichcomprises the fourth quadrant oftrans<strong>for</strong>mation as outlined in the figurebelow.Source: PuttingPeople First, thewhole story(DH 2008)4.7 Despite the change of government itis unlikely that there will be a significantdeparture from the trans<strong>for</strong>mation agenda.While the detail of policy remains to be setout, there is continuing emphasis on theimportance of such key themes asprevention, personalisation, andpartnership. The full coalition ‘programme<strong>for</strong> government’ was published on 20 May2010 and underlined the need “to providemuch more control to individuals and theircarers”, and to extend the greater roll-outof personal budgets. The document alsostated the government’s support <strong>for</strong>

“social responsibility, volunteering andphilanthropy”, and a commitment to “makeit easier <strong>for</strong> people to come together toimprove their communities and help oneanother.” (HMG 2010b)4.8 Social capital is viewed as animportant contribution to improvedoutcomes <strong>for</strong> people who use social care,although it is recognised that “it will not onits own enable people who might need touse social care to meet their needsunaided” (DHCN, 5). The framework <strong>for</strong>exploring social capital within this projectdistinguishes between individual socialcapital (particularly family, friends andneighbours), and neighbourhoodrelationships and community associations.At the time of writing (Spring 2010) theoutcomes from the Building CommunityCapacity work have still to emerge;however, it is anticipated that these willfocus on sharing good practice from anumber of ‘trailblazer authorities’ andevidence on cost-effective interventions. Aseries of case study vignettes on theBuilding Community Capacity websiteoutlines some of the innovations currentlyunderway. These include examples ofpopulation profiling, communitydevelopment, social enterprisedevelopment, auditing communityvolunteering, time banking, homesharing,‘buddy’ schemes, etc.4.9 As we outlined in the first section ofthis paper, the recent statements by thecoalition government on the developmentof the ‘big society’ echo similar themes. Itis evident that ideas of citizenship andreciprocity transcend party politicalboundaries, and particularly in a time ofeconomic pressure, empowering “families,networks, neighbourhoods andcommunities (...) to be bigger and strongerthan be<strong>for</strong>e” has an obvious appeal. (HMG2010a)4.10 A landmark national policydevelopment was the publication of theNeighbourhood Renewal (NR) Strategyaction plan (CO/SEU 2001) with the aimthat no one should be seriouslydisadvantaged by where they live becauseof ‘failing’ local services or a poorenvironment. Funding <strong>for</strong> NR programmeswas initially allocated to the 88 mostdeprived areas in England with theexpectation that the (then) growingbudgets <strong>for</strong> mainstream public serviceswould underpin the NR strategies, and thatthere would be further targeting of themost deprived neighbourhoods. The localdelivery vehicles <strong>for</strong> the NR strategy are<strong>Local</strong> Strategic Partnerships (LSPs)—potentially one of the most importantinnovations in local governance in recentyears.4.11 The final evaluation of theneighbourhood renewal strategy hasrecently been published (DCLG 2010a).Although it concludes that changes in theconditions of the more deprivedneighbourhoods have improved, and thatthe gap with the national average hasclosed, it is clear that they remain a longway behind and are beginning to feel theimpact of the recession. A similar messageemerges from the final evaluation of theNew Deal <strong>for</strong> Communities programme(DCLG 2010b). Here there was also animprovement on most core indicators,especially in people’s feelings about theirneighbourhoods. Stronger relationshipswere established with those agencieshaving a ‘natural’ neighbourhood presence(like the police), but little improvement inthe generation of social capital wasevident.4.12 The identification of pockets ofdeprivation including but extending beyondNR areas led to the introduction of theSafer Stronger Communities Fund (SSCF)in 2006 to focus on these small localities in‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 13

84 local authority areas. Included in theSSCF is the Neighbourhood Element whichprovides funding <strong>for</strong> 100 of the mostdisadvantaged neighbourhoods in Englandto improve the quality of life <strong>for</strong> peopleliving in them, and to ensure serviceproviders are more responsive toneighbourhood needs. Both NR and SSCFare good examples of Barnes’scommunity-level interventions.4.13 Perhaps the main nationalprogramme impinging directly onwork<strong>for</strong>ce development has been theestablishment of NeighbourhoodManagement (NM), an approachdeveloped by the Social Exclusion Unit’sPolicy <strong>Act</strong>ion Team as a means of securingneighbourhood level action to improveservice delivery. The first 20Neighbourhood Management Pathfinderswere announced in July 2001, and asecond round of 15 in December 2003.4.14 Although NM is seen as a way ofencouraging service providers to improveservices in deprived neighbourhoods, italso has a potential role in developingsocial capital and community cohesion. Inparticular it employs a neighbourhoodmanager, supported by a small team, totake overall responsibility at this local level.In addition to the Pathfinders, otherlocalities have developed their own NMschemes drawing upon theNeighbourhood Element (NE) of SSCF—around 80% of local authorities (in around500 neighbourhoods) in receipt of NRF orNE are estimated to be operating suchschemes. Given the heavy financialdependence upon NE, the end of thissource of funding will be a key test of localcommitment.4.15 There has been some evaluation ofthe NM Pathfinders (DCLG 2010b; 2008b).Most of the initiatives covered the followingcomponents:‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 14• use as a tool <strong>for</strong> facilitating therenewal of deprived neighbourhoods• an initial focus upon crime andenvironmental issues• an average target area size below15,000 (some well aboveconventional definitions of a‘neighbourhood’)• an emphasis upon influencingservice providers rather thanengaging in direct service delivery• engagement with a variety ofpartners, notably the police, localauthority, PCT and housingassociations; leadership ispredominantly by the local authority• widespread recognition of theimportance of involving thecommunity.4.16 Nevertheless the evaluators arecautious in their assessment of the impactof NM, observing that it is a challenge toidentify and evaluate measurable impacts,not least in the absence of systematic andcomprehensive small area administrativedata.4.17 The role of policing inneighbourhoods has become hugelysignificant since the publication of theFlanagan Review (Flanagan 2008). Thisproposed that neighbourhood policingshould be at the core of policing inEngland and Wales, as it would help to:• increase community confidence inthe police• increase community involvement inshaping priorities• increase partnership working• promote community cohesion.4.18 Subsequently the Home Officepublished a new strategy on

neighbourhood policing (HO 2010) whichsets out a vision of safe and confidentneighbourhoods everywhere in which allmembers of the public can expect:• to continue to benefit from theirnamed, dedicated neighbourhoodpolicing team including PoliceCommunity Support Officers(PCSOs)• victims to receive a joined upresponse from the police, localcouncil and criminal justice• to be able to have a say in howservices keep them safe andconfident and be able to challengeagencies if expectations are not met• to be confident and able to engagein playing their full role in their ownneighbourhood’s safety.4.19 Importantly, the strategy states thatto keep neighbourhoods truly safe andconfident, the police cannot act alone. It isexpected that all key agencies – health,local council and children’s services – willhave clearly identified lead contacts <strong>for</strong>neighbourhood policing teams. Moreover,the previous government had funded 12areas (and supported a further 100) indeveloping Neighbourhood Agreements tosupport communities in negotiating whatpolice services can do <strong>for</strong> them to keepneighbourhoods safe and confident. Interms of work<strong>for</strong>ce development, there is aproposal <strong>for</strong> further professionalisingneighbourhood policing through trainingand leadership support and a PCSOaccreditation. The main party manifestos allreflected an emphasis on neighbourhoodpolicing themes. The Conservative Partystated a commitment to giving people“democratic control over policing priorities”to empower local communities, whileLabour pledged to establishneighbourhood police teams in every areawith accountability to local people throughmonthly public meetings.4.20 Finally, in the recent publicationPutting the Frontline First (HMG 2009) theLabour government proposed a further raftof measures that bear uponneighbourhoods and the generation ofsocial capital. These include:• Neighbourhood Agreements to bepiloted by the Home Office, whichwill give the public in a local areamore say about how issues wherethey live can best be tackled, andlead to allocations of resources thatbetter reflect community priorities.• The Community Assets Programmewill aim to empower communities byencouraging the transfer of underusedlocal authority assets to localorganisations.• Social Impact Bonds aim to attractnon-government investment intolocal activities with returnsgenerated from a proportion of therelated reduction in governmentspending on acute services.• Social Investment Wholesale Bankto provide capital to organisationsdelivering social impact to supportthe sustainability of socialenterprises.• Civic Health Index to enable peopleto assess how well civic society isfaring and how it can be enabled tothrive.national non-statutory sectorprogrammes4.21 There are several relevant nonstatutorysector programmes that havesome national profile. Perhaps the bestknown of these are time banks,pledgebanks and lifetime neighbourhoods.‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 15

‣ time banks4.22 The concept of time banks is part ofa wider set of ideas often enshrined in theterm ‘co-production’. Much of thetheoretical and practical development ofco-production has come from the UnitedStates and dates back to the 1970s. Itembodies partnership between themonetary economy and “the coreeconomy of home, family, neighbourhood,community and civil society” (Cahn 2008).Co-production and time banks are notsimply a non-monetary alternativeeconomy that provides a mechanism <strong>for</strong>valuing the contribution of people outsideof a <strong>for</strong>mal labour market. Rather, there isalso an explicit ideological and value-basedunderpinning that emphasises principles ofreciprocity and mutuality.4.23 Time banks started in the UK in1998 and offer a model <strong>for</strong> recognising andrewarding family carers. In a time bank,participants earn time credits <strong>for</strong> helpingeach other—one hour of your time entitlesyou to one hour of someone else’s time.Credits are deposited centrally in the timebank and withdrawn when help is needed,with help exchanged through a broker wholinks people up and keeps a record oftransactions. Most time banks have anoffice base and a paid member of staffserving as the broker. Time credits have nomonetary value, so are unlikely to affectcarers’ benefit entitlements. A nationalnetwork of around 200 time banks – TimeBanks UK – is already in operation, andsome programmes are actually identifiedas ‘neighbourhood time banks’(www.timebanking.org).4.24 Another model closely related totime banks features complementarycurrencies within ‘local exchange tradingsystems’ (LETS); as with time banks thisinvolves people creating credits that theycan ‘spend’ with other members. A muchcitedexample of one such complementarycurrency is that of ‘Fueai kippu’ that hasbeen developed in Japan to provide care<strong>for</strong> elderly family members:“Imagine I am living in Tokyo, but myelderly parents live 200 miles away so it isdifficult <strong>for</strong> me to care <strong>for</strong> them. Instead, Icare <strong>for</strong> an elderly person who lives closeby, and I transfer my credits back to myparents. They can then use these to ‘buy’care where they live.” (Halpern 2010, 107)4.25 It might be argued by critics thatsuch a system would not work (or not in anEnglish context) because care is not simplyan exchange commodity, but isfundamentally about the context of arelationship. Nonetheless, Halpern arguesthat because Fueai kippu are earnedthrough care and not money, “the wholetransaction feels different and far moreacceptable. And the evidence shows thatthis system leads to more caring activity,not just displacement.” (Halpern 2010,107)4.26 Halpern has gone further than somecommentators in asking whether suchpositive reciprocity should be activelystimulated by expecting ‘all able adults’ tocontribute a minimum number of hours ofcommunity service. Rather than this beingseen as altruism or volunteering, Halpernargues, it would be ‘true reciprocity’,particularly if the economy of regard wasfurther strengthened through the use ofcomplementary currencies. (Halpern 2010,119)‣ pledgebanks‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 164.27 The Communities in Control whitepaper (DCLG 2008c ) included acommitment to pilot communityPledgebanks during 2009 as a way ofencouraging people to register a pledge toundertake some activity or contributesome resource towards a common goal.Community Pledgebanks could be

collective (‘I pledge to do X if Y otherpeople will join me in doing it’) or individual(‘I pledge to do X’). Collective pledges areharder to work because they have to link inwith someone else’s idea, and the greatestnumber of current pledge schemesconcern environmental issues. There isonly limited data on pledging, but a review(Cotterill and Richardson 2009) concludedthat:• asking people to pledge can lead tobehaviour change, but there is noclear evidence that it is any more orless effective than othercampaigning approaches• asking people to pledge seems towork best if it takes a personalapproach, but it is unclear whether itis the personal approach or thepledging that has an effect• pledging campaigns are most likelyto be successful if they are part of awider promotional campaign,including publicity, incentives,creation of social norms, remindersand cues, but then it is hard toseparate out the effect of the pledge• people are more likely to carry out apledge if it relates to something theywere already thinking about, theyhave been allowed to personalisethe pledge, and the activity is not toochallenging.‣ lifetime neighbourhoods4.28 In the context of an ageingpopulation it is vital to offer inclusive ‘ageproofed’environments that minimise theimpact of disability on independence andsocial participation. Lifetimeneighbourhoods seek to fill this need, butthe concept has yet to feature extensivelyin government guidance or make asignificant impact on mainstream planningpractice. The broad aim is to provide allresidents with the best possible chance of‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 17health, well-being and social inclusion(DCLG 2008d). In a manifesto <strong>for</strong> lifetimeneighbourhoods, Help the Aged proposeten components that should be theminimum requirement.• Basic amenities within reasonablereach: while everyone needs accessto money, healthcare and someshops, neighbourhoods andcommunities that do not providethese can leave older peopleisolated.• Safe, secure and clean streets: thismatters to all age groups but olderpeople are particularly likely to fearcrime. Good lighting, well-kept cleanstreets and a police presenceshould all be prioritised to helppeople feel more confident aboutgetting out and about.• Realistic transport options <strong>for</strong> all:while older people are given free buspasses, many are still unable to getaround because physical impairmentprevents them from using buses, orbecause there are simply no routes.Transport options should beavailable <strong>for</strong> all.• Public seating should be madeavailable in many more places:having somewhere to rest meansthat older people can remain mobile<strong>for</strong> longer in their communities andthat they can enjoy public spaces.• In<strong>for</strong>mation and advice: if no oneknows about them, services mightjust as well not exist. Good adviceand in<strong>for</strong>mation on everythingranging from social care to localvolunteering opportunities areessential <strong>for</strong> older people’s wellbeing.

• Lifetime homes: new homes shouldbe built to Lifetime Homes standardsand people in existing homes shouldhave access to necessary repairsand adaptations to make theirhomes last <strong>for</strong> a lifetime.• Older people’s voices heard: olderpeople must be involved in localdecisions that affect them, and theirvoices heard.• Places to meet and spend time:whether it be a public park, a sharedcommunity centre or a village hall,spaces <strong>for</strong> people to meet are vitallyimportant to all of us and all ages.• Pavements in good repair: allpavements should be smooth andnon-slip, with a maximum differencein paving-slab height of 2.5cm (1inch), so that older people are lesslikely to fall or to have a fear offalling in their local area.• Public toilets should be provided infar greater numbers as they are vitalto the many older people who sufferfrom incontinence; without themmany people are renderedhousebound. (HtA 2008)local programmes4.29 <strong>Local</strong> neighbourhood strategies arevariable. Some, such as <strong>Local</strong> AreaCoordination or Connected <strong>Care</strong>, arebased upon national templates, whilstothers are entirely locally generated. It hasnot been possible in this review ofpublished sources to undertake a fullsurvey of local programmes, but someexamples are given below.‣ <strong>Local</strong> Area Coordination (LAC)4.30 LAC is an innovative way to supportindividuals and families to build a ‘good life’and strengthen the capacity ofcommunities to welcome and includepeople with disabilities. The conceptoriginated in Australia, pioneered by thework of Eddie Bartnick (Bartnick &Chalmers 2007), and has become popularin Scotland. Like the NeighbourhoodManager, the LAC acts as a coordinatorrather than a service provider, and alsocontributes to building inclusivecommunities through partnership betweenindividuals and families, local organisationsand the broader community. An evaluationof the Scottish experience of LAC wasundertaken by Stalker and her colleagues(Stalker 2007), but (as in the case ofNeighbourhood Management) it proveddifficult to extract clearly identified andmeasurable outcomes. However, they dosuggest three areas of achievement: abetter overall quality of life <strong>for</strong> people;specific differences in individuals’ lives; andparticular areas of work such as transitionto adulthood.‣ Connected <strong>Care</strong>‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 184.31 The Connected <strong>Care</strong> model aims toimprove community well-being byreshaping the relationship betweenservices and the communities in whichthey are delivered. The stated aim is toconnect health and social care serviceswith housing, education, employment,community safety, transport and otherservices, based upon a belief that the gapsbetween services can be bridged byensuring that the legitimacy of local userand community voices is recognised. Intheir evaluation of the Connected <strong>Care</strong>Centre in one ward in Hartlepool,Callaghan and Wistow (2008) note that ifcommunity social capital can be builtthrough involvement and devolved power,the role of the state can then become oneof facilitator in a self-sustaining process,rather than a provider of unresponsiveservices. In effect, the production andownership of knowledge would become

the province of the community rather thanthe ‘expert’ professional.4.32 In the case of Hartlepool, acommunity audit was used as the basis <strong>for</strong>specifying a new model <strong>for</strong> ward-basedcommissioning and service delivery whichincluded proposals <strong>for</strong> work<strong>for</strong>cedevelopment such as:• care navigators working on anoutreach basis (and possiblyrecruited from among localresidents) to improve access,promote early interventions, supportchoice and ensure a holisticapproach• a complex care team integratingspecialist health, social care andhousing support <strong>for</strong> residents withlong-term needs• a trans<strong>for</strong>mation coordinator tomanage the service and promotechange in existing services so thatthey are joined up.4.33 This all adds up to a significantchallenge to the traditional model, and theevaluators have been cautious at this stageabout making undue claims of success.(Wistow & Callaghan 2008)than a bolt-on. The hope is that needs canin future be met at a neighbourhood level,with some specialist resources retaining acity-wide focus. There does not appear tobe any independent evaluation of thestrategy.‣ Sheffield Community Portraits4.35 Community Portraits is a project tomeasure how suitable neighbourhoods inSheffield are <strong>for</strong> the needs of older people,and the intention is to score allneighbourhoods against the outcomesidentified in the DH 2006 white paper, OurHealth, Our <strong>Care</strong>, Our Say (improvinghealth and emotional wellbeing; improvingquality of life; making a positivecontribution; exercising choice and control;enjoying freedom from discrimination andharassment; economic wellbeing) to whichhas been added personal dignity andrespect, access to services anddemographic need. The first communityportrait was undertaken in the Darnallneighbourhood and included a series offocus groups in the area at which theCommunity Portrait was discussed. Thisapproach can be understood as a lessradical version of Connected <strong>Care</strong>—oneless likely to challenge existing decisionmakingprocedures.‣ Derby Neighbourhood and Social <strong>Care</strong>Strategy4.34 Derby’s strategy is based upon aneighbourhood mapping exercise whichcharts the correlation between areas ofmultiple deprivation and levels of socialcare need (Derby 2007). One or twoneighbourhoods were found to account <strong>for</strong>high proportions of children on theprotection register, and <strong>for</strong> thoseaccessing adult social care support. Thisapproach is seen as an alternative to thetraditional city-wide needs-led modelbased upon individual needs assessmentand pre-judged eligibility criteria, rather‘Only a <strong>footstep</strong> away’? 194.36 On the basis of the communityportraits, the Sheffield strategy is torefocus neighbourhood delivery across thecity to change services from supporting asmall number of people with highdependency, to early intervention andsupport to larger numbers (Sheffield 2007).This has work<strong>for</strong>ce implications, notablythe development of 16 communitycaseworkers (to act as the case-finding‘eyes and ears’ of their neighbourhoods)and the creation of neighbourhood-basedmulti-disciplinary teams to provide a rapidresponse service and to target people in(or at risk of entering) residential andnursing homes. The Sheffield strategy