issue 1 <strong>2012</strong>Dormice found on our first wildlife bridgeBritain’s first wildlife landbridge is located above theA21 Lamberhurst bypass,in Kent. It was constructedprimarily to retain thehistoric vehicular accesspoint <strong>for</strong> people enteringthe National <strong>Trust</strong>’s ScotneyCastle Estate and wascompleted in 2005. <strong>The</strong>wide roadside verges up tothe edge of the bridge wereplanted with hedgerow treespecies to provide a wildlifelink between land on eitherside of the bridge.Dormice were known tooccupy land directly to thewest (map below area A)and a small wooded area400 metres south east ofthe bridge (C), as well aswithin other areas of theScotney Castle Estate. InApril 2010 a new NDMPsite, using 60 boxes, wasset up to investigate areaspreviously thought tocontain populations ofdormice. Part of the rationalewas to ascertain whetherthe populations divided byAn aerial view of the wildlife bridge over theA21. Areas A & C are where the known dormousepopulation existed be<strong>for</strong>e the bridge was constructed.Area B has been monitored <strong>for</strong> two years with noevidence of dormice, whilst the red dots on the bridgeindicate where dormice have been found during 2011.Athe road would be able toreconnect using the landbridge. Initially 10 nesttubes were placed on theland bridge in vegetationboth on the warm southernside and colder northernside. In October 2010 a nestwas found in one of thetubes, but it was uncertainwhether this was made by adormouse or another smallmammal.In March 2011, the tubeson the bridge were replacedwith 10 new nest boxes. InMay, James Hitchin, one ofScotney Castle’s rangers,spotted a male dormousein one of these boxes and anest in an adjacent box, bothon the southern section ofthe bridge on the westernend. A dormouse was seenagain in this area in June,whilst in July in a differentbox on the northern side ofthe bridge (again adjacentto the western land)another male dormousewas recorded. In Septembera female dormouse, withan unknown number ofnewborn young (as theywere pinkies we decided toleave them undisturbed),was found on the northernsection of the bridge, butthis time bordering theeastern land. Interestinglyin two years of recordingwe have not encounteredany other dormice on landadjacent to the eastern edgeof the bridge (B).What does this reveal?That dormice have used thehabitat to the north andsouth of the road and thatbreeding has successfullyoccurred on the land bridge.So six years after it wascompleted, firm evidencehas been found that dormiceare using Britain’s firstwildlife land bridge.With evidence of a knownpopulation of dormice onland adjacent to the westernedge of the bridge, butnot on the eastern edge,it is tempting to suggestthat the female dormicefound breeding near theCBeastern edge had ‘crossedthe bridge’ from the westernside, but this cannot beproved, without furtherinvestigation.We are currently seekingthe permission of thehighways agency tosurvey other land near tothe eastern edge of thebridge to see if there aredormice in this scrubbyarea, to clarify if this mightbe where the ‘mum’ wefound in September mighthave come from. It will alsoindicate whether anothergroup of dormice, about 750metres away, might be ableto reach the land bridge, asthe habitat between theseareas of the estate seemscurrently to be ‘not ideal’ <strong>for</strong>dormice, the understoreybeing dominated byrhododendron. Animprovement plan is in place<strong>for</strong> this area.Additionally James is restartinganother monitoringsite this year, on a separatepart of the Scotney CastleEstate, some 1.25km away,where evidence suggeststhere are more dormice…there seem to be quite alot on this National <strong>Trust</strong>property!So in a quiet part ofthe Kentish weald newdiscoveries are being madewhich, we hope, will lead tomore wildlife land bridgesbeing considered when roadschemes are planned; afterall we have the evidence thatthey work, but do we havethe political will to makethem appear?Steve Songhurst NDMP<strong>vol</strong>unteer; with help fromfellow monitors JamesHitchin (National <strong>Trust</strong>),Steve Oram (PTES) and DavidScully, (Tunbridge WellsBorough Council).6 the dormouse monitor

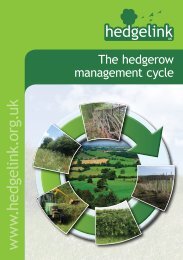

issue 1 <strong>2012</strong>Taking a closer look at dormice in torpor<strong>The</strong>re are now sufficientobservations of torpidanimals each year to throwlight on why they do it.Recordings from nest boxesmade years ago showedthat dormice spent up toabout nine hours per dayin torpor in the early partof the season, falling toless than half an hour perday in the autumn. Wesuggested that this reflectedtheir need to conserveenergy at times when foodwas in short supply. In theautumn (minimal time spenttorpid) there was plenty offood available. But in earlysummer the animals riskedspending more energylooking <strong>for</strong> food thanthey got from the meagreamounts they found. Atthis time, we thought, theywould spend more timetorpid as a way of reducingthe energy cost of remainingcontinuously warm blooded.In other words, torpor wasprobably linked to foodsupply. This was speculationrather than proven fact.However, that study wasbased on relatively fewindividuals. Now the NDMPoffers another way oflooking at the same issuefrom a different direction.Last year over 700 dormicewere found in torpor. <strong>The</strong>percentage of dormiceweighing more than 10g(i.e. eliminating nestlings)that were found torpid eachmonth was calculated. Fromthe results it’s quite clearthat they hardly botheredin August and September,warm months with abundantfruits and seeds available.But early in the season, whenflowers may be finishedand fruits not ready, foodmust be a serious problem.It is at this time that theyeat more insects and alsospend much time in torpor.This is why dormice breedlater in the spring than othersmall mammals. You can’tbe torpid most of the timeand also be producing andraising young.In fact you can see that‘summer torpor’ as anenergy-saving strategy,progressively merges withhibernation (saving energywhen there is no food atall over winter) as winterapproaches in October andNovember. <strong>The</strong>y emergefrom hibernation but stillspend (diminishing) amountsof time inactive with loweredbody temperature until June.<strong>The</strong>y don’t simply wake upwhen hibernation ‘ends’.It’s almost as though theirnatural state is asleep, withonly a small attempt at beingactive in late summer - trulythe ‘dormant mouse’.Given a long series ofdata, which the NDMP isslowly accumulating, itmay be possible to showthe effects of weather andclimate change, based ona comparison of numberstorpid from year to year.Good dormouse years willbe those with lower thanaverage numbers foundin torpor each month; badyears will be ones wheremore animals spend moretime torpid. In turn thismay be related to breedingsuccess. In other words wemay be able to use torpor asan indicator of good and badyears - a nice little study <strong>for</strong>someone to pursue perhaps?Thank you to all the monitors.Pat MorrisJohn Webleythe dormouse monitor 7