Facilitating learning in the workplace - Faculty Development ...

Facilitating learning in the workplace - Faculty Development ...

Facilitating learning in the workplace - Faculty Development ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

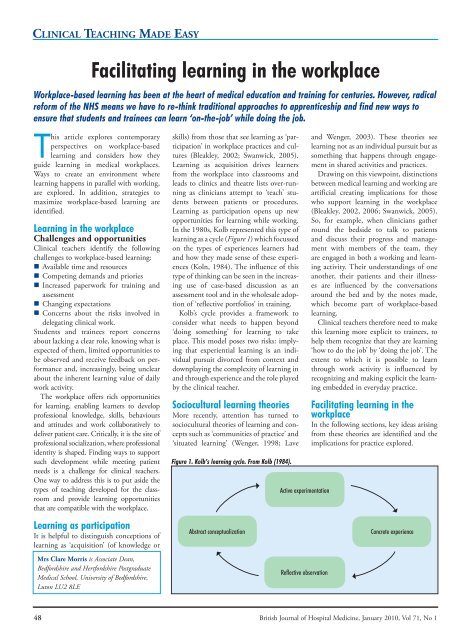

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Teach<strong>in</strong>g Made Easy<strong>Facilitat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong>Workplace-based <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> has been at <strong>the</strong> heart of medical education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for centuries. However, radicalreform of <strong>the</strong> NHS means we have to re-th<strong>in</strong>k traditional approaches to apprenticeship and f<strong>in</strong>d new ways toensure that students and tra<strong>in</strong>ees can learn ‘on-<strong>the</strong>-job’ while do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> job.This article explores contemporaryperspectives on <strong>workplace</strong>-based<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and considers how <strong>the</strong>yguide <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> medical <strong>workplace</strong>s.Ways to create an environment where<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> happens <strong>in</strong> parallel with work<strong>in</strong>g,are explored. In addition, strategies tomaximize <strong>workplace</strong>-based <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> areidentified.Learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong>Challenges and opportunitiesCl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers identify <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>gchallenges to <strong>workplace</strong>-based <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>:• Available time and resources• Compet<strong>in</strong>g demands and priories• Increased paperwork for tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g andassessment• Chang<strong>in</strong>g expectations• Concerns about <strong>the</strong> risks <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong>delegat<strong>in</strong>g cl<strong>in</strong>ical work.Students and tra<strong>in</strong>ees report concernsabout lack<strong>in</strong>g a clear role, know<strong>in</strong>g what isexpected of <strong>the</strong>m, limited opportunities tobe observed and receive feedback on performanceand, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly, be<strong>in</strong>g unclearabout <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> value of dailywork activity.The <strong>workplace</strong> offers rich opportunitiesfor <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, enabl<strong>in</strong>g learners to developprofessional knowledge, skills, behavioursand attitudes and work collaboratively todeliver patient care. Critically, it is <strong>the</strong> site ofprofessional socialization, where professionalidentity is shaped. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g ways to supportsuch development while meet<strong>in</strong>g patientneeds is a challenge for cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers.One way to address this is to put aside <strong>the</strong>types of teach<strong>in</strong>g developed for <strong>the</strong> classroomand provide <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> opportunitiesthat are compatible with <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong>.Learn<strong>in</strong>g as participationIt is helpful to dist<strong>in</strong>guish conceptions of<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> as ‘acquisition’ (of knowledge orMrs Clare Morris is Associate Dean,Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire PostgraduateMedical School, University of Bedfordshire,Luton LU2 8LEskills) from those that see <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> as ‘participation’<strong>in</strong> <strong>workplace</strong> practices and cultures(Bleakley, 2002; Swanwick, 2005).Learn<strong>in</strong>g as acquisition drives learnersfrom <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong> <strong>in</strong>to classrooms andleads to cl<strong>in</strong>ics and <strong>the</strong>atre lists over-runn<strong>in</strong>gas cl<strong>in</strong>icians attempt to ‘teach’ studentsbetween patients or procedures.Learn<strong>in</strong>g as participation opens up newopportunities for <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> while work<strong>in</strong>g.In <strong>the</strong> 1980s, Kolb represented this type of<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> as a cycle (Figure 1) which focussedon <strong>the</strong> types of experiences learners hadand how <strong>the</strong>y made sense of <strong>the</strong>se experiences(Koln, 1984). The <strong>in</strong>fluence of thistype of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g can be seen <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>guse of case-based discussion as anassessment tool and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wholesale adoptionof ‘reflective portfolios’ <strong>in</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.Kolb’s cycle provides a framework toconsider what needs to happen beyond‘do<strong>in</strong>g someth<strong>in</strong>g’ for <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> to takeplace. This model poses two risks: imply<strong>in</strong>gthat experiential <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is an <strong>in</strong>dividualpursuit divorced from context anddownplay<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> complexity of <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>and through experience and <strong>the</strong> role playedby <strong>the</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical teacher.Sociocultural <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong>oriesMore recently, attention has turned tosociocultural <strong>the</strong>ories of <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and conceptssuch as ‘communities of practice’ and‘situated <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>’ (Wenger, 1998; LaveFigure 1. Kolb’s <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> cycle. From Kolb (1984).Abstract conceptualizationActive experimentationReflective observationand Wenger, 2003). These <strong>the</strong>ories see<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> not as an <strong>in</strong>dividual pursuit but assometh<strong>in</strong>g that happens through engagement<strong>in</strong> shared activities and practices.Draw<strong>in</strong>g on this viewpo<strong>in</strong>t, dist<strong>in</strong>ctionsbetween medical <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and work<strong>in</strong>g areartificial creat<strong>in</strong>g implications for thosewho support <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong>(Bleakley, 2002, 2006; Swanwick, 2005).So, for example, when cl<strong>in</strong>icians ga<strong>the</strong>rround <strong>the</strong> bedside to talk to patientsand discuss <strong>the</strong>ir progress and managementwith members of <strong>the</strong> team, <strong>the</strong>yare engaged <strong>in</strong> both a work<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>activity. Their understand<strong>in</strong>gs of oneano<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>ir patients and <strong>the</strong>ir illnessesare <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>the</strong> conversationsaround <strong>the</strong> bed and by <strong>the</strong> notes made,which become part of <strong>workplace</strong>-based<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.Cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers <strong>the</strong>refore need to makethis <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> more explicit to tra<strong>in</strong>ees, tohelp <strong>the</strong>m recognize that <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>‘how to do <strong>the</strong> job’ by ‘do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> job’. Theextent to which it is possible to learnthrough work activity is <strong>in</strong>fluenced byrecogniz<strong>in</strong>g and mak<strong>in</strong>g explicit <strong>the</strong> <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>embedded <strong>in</strong> everyday practice.<strong>Facilitat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>workplace</strong>In <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g sections, key ideas aris<strong>in</strong>gfrom <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>ories are identified and <strong>the</strong>implications for practice explored.Concrete experience48 British Journal of Hospital Medic<strong>in</strong>e, January 2010, Vol 71, No 1BJHM_48_50_CTME_Workplace.<strong>in</strong>dd 48 23/12/09 16:50:44

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Teach<strong>in</strong>g Made EasyLearn<strong>in</strong>g is part of everyday lifeIf <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is seen as an <strong>in</strong>tegral part ofwork<strong>in</strong>g, cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers need to make<strong>the</strong> <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> more explicit by identify<strong>in</strong>gspecific <strong>workplace</strong> cultures and practicesand help<strong>in</strong>g learners ‘make sense’ of what<strong>the</strong>y see, hear, sense and do. Strategies<strong>in</strong>clude:• Label <strong>the</strong> <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> opportunity, e.g. ‘wehave a <strong>the</strong>atre list this afternoon and weneed to consent patients this morn<strong>in</strong>g. Itwould be a great opportunity for you tolearn more about how to expla<strong>in</strong> proceduresand ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g patient consent.’• Establish prior experience and negotiatea <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> goal, e.g. ‘so, you haveexperience of consent<strong>in</strong>g patients forrout<strong>in</strong>e procedures, so why don’t wework toge<strong>the</strong>r this morn<strong>in</strong>g to consentpatients about to undergo more complexprocedures, with <strong>the</strong> aim be<strong>in</strong>gthat you will be able to do this <strong>in</strong>dependentlynext time?’• Prime for <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> through observ<strong>in</strong>g,e.g. ‘<strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ic this morn<strong>in</strong>g we are likelyto see patients who are booked <strong>in</strong> forcaesarean section. While you observe,notice <strong>the</strong> reasons given for request<strong>in</strong>gelective section and consider how youwould respond if <strong>in</strong> my shoes.’• Workplace-based assessment tools canbe used to identify opportunities for<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and development through<strong>workplace</strong>-based activity, e.g. ‘I noticedyou were struggl<strong>in</strong>g with putt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>that l<strong>in</strong>e, why don’t you arrange towork with one of <strong>the</strong> anaes<strong>the</strong>tists for<strong>the</strong> day and get some extra experience<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre?’Workplaces need to be made<strong>in</strong>vitational for all learnersStudents and tra<strong>in</strong>ees who are made to feelwelcome are more likely to actively engage<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> full range of <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> opportunitiesprovided and to seek to play an active role<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> team. Simple strategies like ensur<strong>in</strong>gstudents are <strong>in</strong>troduced by name, have aperiod of orientation to <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong> and<strong>the</strong> roles of o<strong>the</strong>r team members can makea big difference. Billett (2002, 2004) suggeststhat <strong>workplace</strong>s are not necessarily‘<strong>in</strong>vitational’ to all learners, and may beshaped, for example, by students’ priorexperiences, <strong>the</strong>ir gender, socioeconomicbackground or apparent differences <strong>in</strong>motivation, enthusiasm or <strong>in</strong>terest.Cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers need to create <strong>the</strong> rightconditions for <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and ensure certa<strong>in</strong>types of learners are not disadvantaged.For example, tra<strong>in</strong>ees who seem to lack<strong>in</strong>terest, confidence or capability for aparticular specialty need just as muchopportunity to participate (if not more)than those who have a natural flair or<strong>in</strong>terest.Learn<strong>in</strong>g happens <strong>in</strong> acommunity of practiceTeams can be seen as potential ‘communitiesof practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 2003),identified by common <strong>in</strong>terests and sharedexpertise. To make <strong>the</strong> most of that expertise,all members of <strong>the</strong> community shouldbe engaged <strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.Learners readily identify colleagues, teammembers, patients and carers who help<strong>the</strong>m ‘fit <strong>in</strong>’ to new sett<strong>in</strong>gs and who makepositive contributions to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.These <strong>in</strong>dividuals may not have a formallyrecognized teach<strong>in</strong>g role, for example:• Patient feedback is very powerful <strong>in</strong>re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g practice or seek<strong>in</strong>g newways to do th<strong>in</strong>gs• Students and tra<strong>in</strong>ees learn from eacho<strong>the</strong>r (‘I f<strong>in</strong>d it helpful to hold it thisway’) and share experiences (‘I saw agreat case <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre yesterday’)• Junior medical staff guide less experiencedcolleagues <strong>in</strong> ways of exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gpatients, <strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g charts or testresults and prioritiz<strong>in</strong>g workloads• Nurs<strong>in</strong>g colleagues help newcomers getto grips with ward procedures and protocolsand identify ways to effectivelywork with particular team members.By acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> role played by allmembers of your community and valu<strong>in</strong>git explicitly, learners are encouraged tolook beyond <strong>the</strong>ir immediate supervisorfor guidance.Learn<strong>in</strong>g happens throughparticipationLearn<strong>in</strong>g is most effective when learnersare given opportunities to engage actively<strong>in</strong> real <strong>workplace</strong> activity. Such opportunitiesare bounded by compet<strong>in</strong>g demands,concerns and priorities, <strong>the</strong> complexity of<strong>the</strong> activity, <strong>the</strong> potential risks <strong>in</strong>volved,<strong>the</strong> competence and confidence of <strong>the</strong>learner, <strong>the</strong> time available and <strong>the</strong> will<strong>in</strong>gness(and consent) of patients to be<strong>in</strong>volved. With adequate preparation and‘safety nett<strong>in</strong>g’, cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers can delegatesome complete tasks to learnerswhereas o<strong>the</strong>r opportunities require teachersto work <strong>in</strong> parallel with learners, delegat<strong>in</strong>gappropriate aspects of work <strong>in</strong> orderto <strong>in</strong>crease confidence and competence.One of <strong>the</strong> ways <strong>in</strong> which teachers can‘safety net’ is through <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> needs analysis(McKimm and Swanwick, 2009). Abrief yet really focussed conversation witha tra<strong>in</strong>ee can <strong>in</strong>form decision mak<strong>in</strong>gabout what to delegate and appropriatesupport strategies. This will usually <strong>in</strong>cludef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g out what <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ee knows, wha<strong>the</strong>/she has done before that is of relevance,any concerns or anxieties he/she has aboutwhat is proposed and an offer of back-upsupport (a rescue strategy) to be used ifth<strong>in</strong>gs don’t go accord<strong>in</strong>g to plan.For example, a tra<strong>in</strong>ee might not yet beready to perform a complete surgical procedure.He/she may, however, be ready totake <strong>the</strong> history, perform <strong>the</strong> exam<strong>in</strong>ation,consent <strong>the</strong> patient, prep <strong>the</strong> patient andperform one part of <strong>the</strong> procedure, monitor<strong>in</strong> recovery and write up <strong>the</strong> charts.This gives <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ee a sense of tak<strong>in</strong>gresponsibility for <strong>the</strong> patient’s managementand time to focus his/her attentionfully on <strong>the</strong> aspects he/she is not yet do<strong>in</strong>g,but might do next time.Workplace-based assessments provide aprofile of tra<strong>in</strong>ee performance, enabl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical teacher to spot obvious gaps <strong>in</strong>ei<strong>the</strong>r experience or competence. Thesegaps can become <strong>the</strong> focus on cl<strong>in</strong>icalteach<strong>in</strong>g, with <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ee be<strong>in</strong>g guided toexperiences that help meet <strong>the</strong>ir developmentneeds.Foster<strong>in</strong>g ‘horizontal’ <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>‘Learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> work-based contexts<strong>in</strong>volves students hav<strong>in</strong>g to come toterms with a dual agenda. They notonly have to learn how to draw upon<strong>the</strong>ir formal <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and use it to<strong>in</strong>terrogate <strong>workplace</strong> practices; <strong>the</strong>yalso have to learn how to participate<strong>in</strong> <strong>workplace</strong> activities and cultures’(Griffiths and Guile, 1999).Formal education tends to focus on ‘vertical’<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, <strong>the</strong> accumulation of knowledge.In <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong>, ‘horizontal’ <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>,tak<strong>in</strong>g what you know to make senseof <strong>the</strong> situations you encounter or adapt<strong>in</strong>gwhat you can already do to fit anunexpected presentation is just as impor-British Journal of Hospital Medic<strong>in</strong>e, January 2010, Vol 71, No 1 49BJHM_48_50_CTME_Workplace.<strong>in</strong>dd 49 23/12/09 16:50:45

Cl<strong>in</strong>iCal TeaCh<strong>in</strong>g Made easytant. Medical students and tra<strong>in</strong>ees moverapidly from one <strong>workplace</strong> to ano<strong>the</strong>r andneed to identify and respond to <strong>the</strong> nuanceddifferences between one sett<strong>in</strong>g or teamand ano<strong>the</strong>r. For example, all doctors rout<strong>in</strong>elytake a history from <strong>the</strong>ir patients,but <strong>the</strong>re are significant differences <strong>in</strong>approach across specialties and sett<strong>in</strong>gs.Cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers can help this process bymak<strong>in</strong>g expectations explicit (e.g. preferredstyles of dress, ways of address<strong>in</strong>g colleaguesand patients, format for writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>notes or construct<strong>in</strong>g letters).Horizontal <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> also needs to helplearners activate <strong>the</strong>ir formal <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>(ga<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classroom) to make sense ofcl<strong>in</strong>ical encounters. View<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>g as adialogue (ra<strong>the</strong>r than a monologue) andus<strong>in</strong>g appropriate question<strong>in</strong>g strategies isparticularly effective. Socratic questionscan be used to explore what learners knowand help <strong>the</strong>m make connections to what<strong>the</strong>y see. Heuristic-type questions, designedto promote <strong>the</strong> student’s own self-directed<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, are also important.Learn<strong>in</strong>g through talk<strong>in</strong>gSocial <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong>orists suggest that ‘talk’is a central part of practice. Learners needto ‘learn to talk <strong>the</strong>ir way <strong>in</strong>to expertise’ra<strong>the</strong>r than just learn from <strong>the</strong> talk of anexpert (Lave and Wenger, 2003).Many aspects of medical practice areunseen, tak<strong>in</strong>g place <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ds of practitioners,engaged <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>ternal dialogueKEY POINTS• Make sure your <strong>workplace</strong> is <strong>in</strong>vitational for all students and tra<strong>in</strong>ees.• Make opportunities for <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> from everyday work explicit.based around differential diagnosis, cl<strong>in</strong>icalreason<strong>in</strong>g, management plann<strong>in</strong>g andexplor<strong>in</strong>g prognosis. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers needto f<strong>in</strong>d ways to make <strong>the</strong>ir th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g accessibleto <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ee and access <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ee’sth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g as a way of ensur<strong>in</strong>g he/she is ontrack. Strategies <strong>in</strong>clude:‘Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g aloud’Narratives can be provided as we teach askill or procedure, or along <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>es of‘what I am struggl<strong>in</strong>g with here is…’ or ‘Iam weigh<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>the</strong> options of x vs ybecause...’.Tra<strong>in</strong>ee talkMany cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers have set ways <strong>the</strong>ylike tra<strong>in</strong>ees to present patients, reflect<strong>in</strong>gways <strong>in</strong> which thoughts are organized <strong>in</strong>order to formulate a diagnosis or managementplan. By be<strong>in</strong>g clear with tra<strong>in</strong>ees thatthis talk<strong>in</strong>g prompts a way of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, youare labell<strong>in</strong>g it as a teach<strong>in</strong>g strategy ra<strong>the</strong>rthan a personal quirk and help<strong>in</strong>g learnersto ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to how medic<strong>in</strong>e is practised<strong>in</strong> specific contexts. These ways oftalk<strong>in</strong>g about patients reveal cultural practices.For example, <strong>the</strong> way a patient ispresented <strong>in</strong> surgery is different from medic<strong>in</strong>ewhich is different from psychiatry.Case-based discussionThis is designed to explore <strong>the</strong> th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gbeh<strong>in</strong>d practice. It provides an opportunityfor learners to make <strong>the</strong>ir th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g explicit• Provide opportunities for learners to be actively <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> all aspects of patient care.• Value and make use of <strong>the</strong> expertise of all members of your community, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g patients.• Help tra<strong>in</strong>ees to learn from your talk and to learn to talk medic<strong>in</strong>e.and develop ideas. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers canmake <strong>the</strong> most of <strong>the</strong>se opportunities byus<strong>in</strong>g questions that require <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ee toprovide a rationale for decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g.For example, ‘you decided to admit thispatient, can you tell me more about <strong>the</strong>factors that you took <strong>in</strong>to account… howmight you justify send<strong>in</strong>g this same patienthome… who else <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> team did you<strong>in</strong>volve or could you <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>in</strong> that decision-mak<strong>in</strong>gprocess?’ConclusionsWorkplace-based <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> might be underthreat, but it has never been more important.By draw<strong>in</strong>g upon contemporary viewson <strong>workplace</strong>-based <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, cl<strong>in</strong>icians canbuild upon <strong>the</strong> sound traditions of apprenticeshipand value <strong>the</strong> <strong>workplace</strong> as a key sitefor medical <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and practice. BJHMConflict of <strong>in</strong>terest: none.Billett S (2002) Toward a <strong>workplace</strong> pedagogy:guidance, participation and engagement. AdultEducation Quarterly 53(1): 27–43Billett S (2004) Workplace participatory practices:conceptualis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>workplace</strong>s as <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>environments. Journal of Workplace Learn<strong>in</strong>g16(6): 312–24Bleakley A (2002) Pre-registration house officers andward based <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>: a new apprenticeship model.Med Educ 36: 9–15Bleakley A (2006) Broaden<strong>in</strong>g conceptions of<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> medical education: <strong>the</strong> message fromteam-work<strong>in</strong>g. Med Educ 40(2): 150–7Griffiths T, Guile D (1999) Pedagogy <strong>in</strong> workbasedcontexts. In: Mortimore P, ed. Understand<strong>in</strong>gPedagogy and it’s impact on <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>. Sage,London: 155–74Kolb D (1984) Experiential Learn<strong>in</strong>g. Prentice Hall,Englewood Cliffs, NJLave J, Wenger E (2003) Situated Learn<strong>in</strong>g:Legitimate Peripheral Participation. CambridgeUniversity Press, CambridgeMcKimm J, Swanwick T (2009) Assess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>needs. Br J Hosp Med 70(6): 290–3Swanwick T (2005) Informal <strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong>postgraduate medical education: from cognitivismto ‘culturism’. Med Educ 39(8): 859–65Wenger E (1998) Communities of Practice: Learn<strong>in</strong>g,Mean<strong>in</strong>g and Identity. Cambridge University Press,CambridgeThis series of articles for cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers was orig<strong>in</strong>ally commissioned as a suite of e-<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> modules for <strong>the</strong> London Deanery. Both <strong>the</strong> series and e-<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong>modules were designed and edited by Judy McKimm and Tim Swanwick. The London Deanery e-<strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g</strong> modules for cl<strong>in</strong>ical teachers are open access andavailable at www.londondeanery.ac.uk/facultydevelopmentEach module takes 30–60 m<strong>in</strong>utes to complete and proof of completion is available <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form of a pr<strong>in</strong>ted certificate. Forthcom<strong>in</strong>g articles <strong>in</strong> this series <strong>in</strong>clude:Teach<strong>in</strong>g cl<strong>in</strong>ical skills Simulation Involv<strong>in</strong>g patients <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical teach<strong>in</strong>gInterprofessional education Manag<strong>in</strong>g poor performance Introduction to educational researchDiversity, equal opportunities and human rights50 British Journal of Hospital Medic<strong>in</strong>e, January 2010, Vol 71, No 1BJHM_48_50_CTME_Workplace.<strong>in</strong>dd 50 23/12/09 16:50:51