Rackham Graduate School - University of Michigan

Rackham Graduate School - University of Michigan

Rackham Graduate School - University of Michigan

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

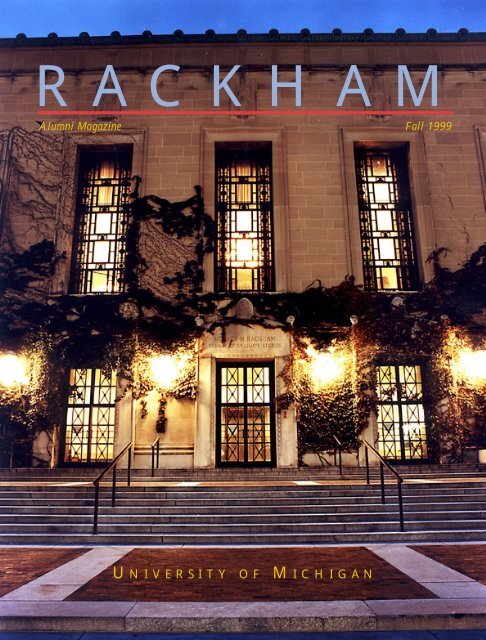

RACKHAMAlumni Magazine Fall 1999U NIVERSITY OF M ICHIGAN

RACKHAMAlumni MagazinePublished annually by the Horace H. <strong>Rackham</strong><strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> StudiesEarl LewisVice Provost for Academic Affairs-<strong>Graduate</strong> Studies andDean, Horace H. <strong>Rackham</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> StudiesJill McDonoughAssistant to the Dean for Development and External RelationsKathryn D. HolmesSenior Development OfficerEditor: Elyse Rubin BuchananWriter: Jeffrey MortimerDesigner: Rose AndersonCover Photo: Philip DatilloContributing Photographers: Yvette Amstelveen,Salvatore Cerchio, Danielle Cholewiak, Jane Hamblin,Jim Hansen, Sharon Herbert, Jim Lang,Ron Midura, Bill Wood<strong>Rackham</strong> Alumni Magazine welcomes your comments.Please send correspondence to Elyse Rubin Buchanan, Editor915 East Washington Street, Ann Arbor, <strong>Michigan</strong> 48109-1070or e-mail: elyserbu@umich.eduCONTENTSalumni pr<strong>of</strong>iles2 Detective on a Dig8 Research is a Team Sport“Two roads diverged in 4a wood and I – I took theone less traveled by.”<strong>Rackham</strong> Executive BoardFrederick Amrine, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> GermanicLanguages and LiteraturesCeleste Brusati, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> History <strong>of</strong> ArtMary Anne Carroll, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Atmospheric,Oceanic, and Space Sciences and ChemistryRuth Dunkle, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Social WorkPhoebe Ellsworth, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> PsychologyGe<strong>of</strong>frey Eley, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> HistoryDavid Engelke, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Biological ChemistryNancy Florida, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Asian Languages and CulturesSherman James, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> EpidemiologyBobbi Low, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources and EnvironmentCharlotte A. Otto, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Natural Sciences, DearbornJames Penner-Hahn, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> ChemistryJames Porter, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Classical StudiesNancy Reame, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> NursingBeverly Schmoll, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Physical Therapy, FlintElizabeth Sears, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> History <strong>of</strong> ArtLynn Walter, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Geological ScienceDavid Wigston, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Biology, Flint<strong>Rackham</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> GovernorsLee C. Bollinger, Chairman; President, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong>Earl Lewis, Secretary; Dean, Horace H. <strong>Rackham</strong> <strong>School</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> StudiesBilly E. Frye, Provost and Vice President forAcademic Affairs, Emory <strong>University</strong>Melvin Oliver, Vice President for Asset Building andCommunity Development Program, The Ford FoundationMarina v. N. Whitman, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Business Administrationand Public Policy, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong>student pr<strong>of</strong>iles10 Salvatore Cerchi<strong>of</strong>eature articleIn•ter•dis•ci•pli•nary 6Yvette Amstelveen 12

From the DeanWelcome to the inaugural issue <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Rackham</strong>Alumni Magazine. Whether you graduated fiftyyears ago or just this past May, you belong to alarge and far-flung group <strong>of</strong> talented individuals who comprisethe <strong>Rackham</strong> alumni body: more than 85,000 peoplein all 50 states and 103 countries. With this publication, wehope to reconnect you with the <strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>School</strong> by pr<strong>of</strong>ilingfive people whose lives and careers reflect the diversityand richness <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Rackham</strong> family.As one <strong>of</strong> the world’s foremost institutions <strong>of</strong> graduateeducation, <strong>Rackham</strong> oversees the training <strong>of</strong> the next generation<strong>of</strong> researchers, scholars, educators, policy-makers,and artists. In this issue we pr<strong>of</strong>ile Yvette Amstelveen andSalvatore Cerchio, two <strong>of</strong> our outstanding graduate studentswhose work already embodies the sophistication,creativity, and intellectual rigor that bodes well for theirfuture careers.<strong>Rackham</strong> is proud to number among our alumni countlessindividuals whose work has a tremendous impact onthe decisions being made every day in every sector,whether private or public. Whatever their field, the mosteffective leaders are those who can think and work “outsidethe box,” can apply their own intelligence and experienceto a variety <strong>of</strong> situations and be successful. The threealumni featured in this issue — Wayne Patterson, AndreaBerlin, and Kathe Derwin — have taken what they learnedin graduate school and moved in directions they may nothave anticipated when they were students. They each canclaim important accomplishments within their pr<strong>of</strong>essionaland personal lives, and are able to respond to whateverchallenges they may encounter.As the <strong>University</strong> moves into the next millennium, wefind that traditional academic disciplines grow less rigidand intellectual boundaries more porous, and that fruitfulwork is taking place among scholars who actively engagein conversations with colleagues from a variety <strong>of</strong> fields.<strong>Rackham</strong> is at the center <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong>’s moststimulating interdisciplinary initiatives, for we work withindividual departments and faculty members to promote collaborative research and teaching. “Interdisciplinary” detailsthe significance <strong>of</strong> interdisciplinarity and its implications for the future <strong>of</strong> graduate education.The 21st Century bodes well for the <strong>Rackham</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>School</strong>. I hope you enjoy this new magazine and that youwill continue to be proud <strong>of</strong> the legacy you share as part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Rackham</strong> family.Best regards,Earl LewisPhoto by Bill Wood

A L U M N I P R O F I L E S2DEInterdisciplinarity? Archeologypractically invented it, saysAndrea Berlin.“To me, it’s the most inherentlyinterdisciplinary field in the academy,”she says. “You cannot pursue itwithout understanding a great dealabout history, the classics, historiography,geography, geology, andmaterials science.”Any one <strong>of</strong> them — and manyothers — could come into play atany time, adds Berlin, an AssistantPr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Classical Archeologyat the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Minnesota whoreceived her PhD in classical artand archeology from U-M(<strong>Michigan</strong>, that is) in 1988. “Theamount <strong>of</strong> stuff that I draw uponevery day that I’m standing out on asite … what part <strong>of</strong> graduate schoolprepared me for this? A small part;the rest I had to pick up on myown,” she says. “Any successfulpracticing archeologist draws uponthings that by rights fall within anumber <strong>of</strong> departments, but theyare all truly part <strong>of</strong> the core <strong>of</strong>archeology. There is no end to whatis relevant.”Basically, anything that helps t<strong>of</strong>ill in a blank is useful, and imagination,to paraphrase Einsteinslightly, is at least as important asknowledge. The fondness <strong>of</strong> archeologistsfor detective fiction isalmost a cliché. “Archeologists as agroup are some <strong>of</strong> the biggest fanson earth,” says Berlin. “It must besomething that attracts that kind <strong>of</strong>mind.”TECTIVE ON A DIGPhoto by Jim HansenAs she herself says,her field is “detectivework <strong>of</strong> the most funkind.” With, <strong>of</strong> course, atleast one conspicuousdifference. In dealingwith the non-literaryrecord, “you never knowif you’re right. You mayconstruct a scenario thathangs together in a waythat people in relatedfields find compellingand helpful, a little bitlike what in a court <strong>of</strong>law is circumstantial evidence,and when youaccumulate enough <strong>of</strong> it,you tend to feel you’vefound out the truth, butit’s not provable in thesense <strong>of</strong> a science problem.In the end, it’s likeone <strong>of</strong> those detectivestories. You need a storyline. You need imagination.”Take the pottery shestudied last summer at a dig inTurkey on the site <strong>of</strong> ancient Troy,pottery for the most part excavatedthe year before. Pottery is her specialty,and she was good enough atunearthing and interpreting it tomake a living as a free-lancer for adecade while her husband taughtand their two children were born,not to mention good enough to landa tenure-track job at Minnesotadespite 10 years out <strong>of</strong> the academicloop. She is one who can, in the“. . . it’s like one <strong>of</strong> thosedetective stories. You need astoryline. You need imagination.”words <strong>of</strong> the poet William Blake,“see a world in a grain <strong>of</strong> sand.”“Half the job is finding it and theother half is explaining what it isand why it’s there,” she says. Thematerial she had found dated fromthe 4th Century BC, a time whenTroy was largely invisible historically.

Thanks to the Iliad and theOdyssey, “Troy was to theGreeks what Plymouth Rockand the Liberty Bell are to us,” shesays. Ironically, the tales that made itfamous are generally regarded asmythical, while the real life <strong>of</strong> thecity centuries later is ignored. Butfrom what she collected and studied,it seemed clear to Berlin that somethingsignificant was going on.“If somebody had found this material40 years ago,” she says, “theywouldn’t have paid much attention toit, primarily because it wasn’t associatedwith any architecture but alsobecause people didn’t pay muchattention to small finds.”But the notion <strong>of</strong> what is worthy<strong>of</strong> investigation is different now. “Ilooked at all this material, a lot <strong>of</strong> itvery nice, a lot <strong>of</strong> it imported fromAthens, and I simply asked what’s itdoing here and what does it mean?”It was clearly not locally produced,and clearly not intended for householdutility.“You can’t have all this materialhere without somebody bringing it,”she says. “Why did they bring ithere? Why then? Why in this space?What is happening in the middle <strong>of</strong>the 4th Century? What is the connectionbetween Troy and Athens, whichis a sea away?”Cue the knowledge <strong>of</strong> history. Cuethe imagination. “The long and short<strong>of</strong> it is that this was the period whenPhilip II <strong>of</strong> Macedon, Alexander theGreat’s father, was threatening totake away the independence <strong>of</strong> theGreek world and Athens was castingherself in the role <strong>of</strong> the savior <strong>of</strong>Greece and invoking the help <strong>of</strong>many <strong>of</strong> her daughter cities, hercolonies, one <strong>of</strong> which was a city justa morning’s walk away from Troy.Athens anchored her navy there for atime, probably because it was a safeplace, out <strong>of</strong> the reach <strong>of</strong> Philip.”But the area was strategicallyimportant for other, less tangible,reasons, Berlin believes. “I thinkTroy was suddenly very helpfullybeing invoked as a prestigious symbol<strong>of</strong> Greek military hegemony andpolitical prominence,” she says.“Suddenly, in the middle <strong>of</strong> the 4thCentury, in an episode that is unremarkedupon by any contemporaryhistorians, Troy became a symbolagain and people came to visit theshrine at Troy and they brought dedications,and that’s what we found,their dedications.”“The need <strong>of</strong> the Athenians toinvoke not only actual militarystrength but also old symbols lendsmore depth to their fight againstPhilip, a fight they lost. The fact thatTroy and the sagas associated with itbecame important suddenly at thattime tells you two things. One is thatthey were not some constant part <strong>of</strong>the Greek self-consciousness or elsethere would have been evidence <strong>of</strong>concerted activity and dedications atthe site for the previous hundredyears, and in fact there wasn’t. Theother is that the Athenians apparentlydidn’t hesitate to invoke this powerfulsymbol just when it was necessary,” abehavior that makes them seem verymodern.Like their contemporary counterparts,they had no qualms aboutwrapping themselves in the flag, as itwere. Such an insight not only addsto our understanding <strong>of</strong> these people,but also makes them seem lessremote, less alien to ourselves.“This is an episode that nobodyknew about because nobody in antiquitywrote about it,” says Berlin,“and if we hadn’t found this material,nobody would know about it yet.Photo by Sharon HerbertAnd also if nobody bothered to lookat the material and ask what it wasdoing there and look for a contextthat would explain it. That is myfavorite thing to do. Nothing givesme a bigger charge than that.”After all, as she points out, “historyis made by everybody all <strong>of</strong> the timeand we are informed in a literarysense <strong>of</strong> about one-half <strong>of</strong> one percent<strong>of</strong> it. What I think I do is putpages back into the history books.” ■3

A L U M N I P R O F I L E S4Two roads diverged in a woodand I–Itook the one less traveled by.When Wayne Pattersontalks about a broaderpalette <strong>of</strong> possibilitiesfor people withPhDs, he need onlypoint to his own.While a graduate student, he“imported” an inner-city math educationprogram from California to<strong>Michigan</strong> and later helped establishit nationally. He returned tohis native Canada for a time,became assistant to the DeputyPrime Minister, and eventuallyserved four years as Vice President<strong>of</strong> the national Liberal Party. Backin the states, he launched the computerscience program at the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> New Orleans,became the school’s Associate ViceChancellor for Research, thenmoved on to the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>Charleston, South Carolina as VicePresident <strong>of</strong> Research and Dean <strong>of</strong>the <strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>School</strong>.He has just returned to the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Charleston, SouthCarolina, from a leave duringwhich he served as the Dean inResidence at the Council <strong>of</strong><strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>School</strong>s in Washington,D.C., conducting a national studyon graduate certificate programsand exhorting all and sundry toconsider more options.“I can serve this world by bringingone set <strong>of</strong> talents to differentfields,” he says. “I wouldn’t be satisfieddevoting an entire career tojust math, or just politics. The purpose<strong>of</strong> a PhD is not just to producefaculty for Research I institutions,doing the same things theirfaculty advisors did before them.The earlier that graduate studentscan see other ways to use theirdegrees, the healthier graduateeducation will be.”His intention was to become acollege mathematics pr<strong>of</strong>essorwhen he enrolled in the <strong>University</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> Math Department’sdoctoral program in the 1960s, andthat was typical <strong>of</strong> such students atthe time. Higher education inNorth America was mushrooming,and the demand for traditionallytrained academics was high.As part <strong>of</strong> the U-M program, hewas sent to a different research– Robert Frostinstitution each summer. On one <strong>of</strong>those jaunts, to Berkeley, he metthe founder <strong>of</strong> Project SEED, aprogram that put college facultyand graduate students into innercityclassrooms to teach advancedalgebra and calculus to fifth andsixth graders. Patterson becameconsumed by the project, devoting“The earlier thatgraduate students cansee other ways to usetheir degrees, thehealthier graduateeducation will be.”40 or more hours a week to itwhile doing his thesis research intopology, although he still finishedhis PhD earlier than most <strong>of</strong> hisclassmates. “Although my ProjectSEED activities were not universallysupported by the powers thatbe in the U-M Math Department,

Photo by Jane Hamblinmy thesis advisor, Frank Raymond,and my other committee membersalways expressed confidence in mycommitment as a research mathematician.”He then devoted 10 years full-timeto Project SEED before his return toCanada and subsequent careers. Hecontinues to volunteer for the program,whose long-term results havebeen stunning.“Between 30 and 40 studies <strong>of</strong> ithave been done over the years,” hesays. “One was in the Dallas schooldistrict, and I don’t know <strong>of</strong> anyother study like this in education.They did a statistical analysis <strong>of</strong> studentswho were in Project SEED infourth, fifth and sixth grades, comparedto a matched control group,and followed them through 12thgrade. A minimum <strong>of</strong> six years later,there were still statistically significantdifferences in math achievement,fewer dropouts, better retention,more students taking collegeprep mathematics and so on. They’vebeen following up Project SEED studentsfor 10 years now, and theresults hold up.”Patterson’s current work couldprove comparably dramatic in itsown way, albeit at the other end <strong>of</strong>the educational continuum. He’s justfinished a book, based on surveydata from 200 schools, on policiesand procedures for graduatecertificate programs, just one<strong>of</strong> the many alternatives to traditionalgraduate degree programsthat have materialized inthe last decade or so.“Certificate programs generallyare shorter-term, nondegreeprograms, <strong>of</strong>fered atvarious levels by pr<strong>of</strong>essional,undergraduate, continuing educationand graduate schools,”Patterson explains. “We’ve tended touse the term graduate certificate tomean that the content <strong>of</strong> the curriculumis part <strong>of</strong> the approved graduatecurriculum <strong>of</strong> the university. Let’ssay you have a number <strong>of</strong> courses inthe master’s <strong>of</strong> public administrationprogram on geographic informationsystems. You might define a set <strong>of</strong>four or five courses as ‘geographicinformation systems’ and re<strong>of</strong>ferthem as a certificate in that area.”Patterson vividly recalls the dayswhen a master’s degree itself wasgenerally regarded as a sort <strong>of</strong> consolationprize for doctoral candidateswho, for one reason or another, fellby the wayside.But, he says, “In the last 20 years,the number <strong>of</strong> students doing whatwe would call pr<strong>of</strong>essional master’sdegrees has just exploded. We awardeight times as many master’s degreesnationally as we do doctorates. Manymore schools have a specific curriculumdesigned for the master’s. Therequirement to write a thesis for amaster’s has virtually disappeared,and that’s an indication <strong>of</strong> a morepr<strong>of</strong>essional than research orientationto that degree. This whole move tocertificates and other forms <strong>of</strong> postbaccalaureateeducation continues atrend that really started with the pr<strong>of</strong>essionalmaster’s degree.”“Post-baccalaureate education” isthe phrase <strong>of</strong> choice at the Council<strong>of</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>School</strong>s. “It certainlyincludes our traditional models formaster’s and doctoral education,” hesays, “but it also brings in all theeducational needs a person mighthave once they’re beyond the firstdegree level. A remarkable number<strong>of</strong> two-year institutions are involvedin post-baccalaureate education, aswell as something like 1,400 corporateuniversities. The face <strong>of</strong> postgraduateeducation is really changinga great deal.”The reality is a given. Theresponse is not. “I guess the questionis whether it’s something the graduateschools in the country wish toendorse, participate in, ignore, fight,or take a leadership role in,” saysPatterson. “There are a lot <strong>of</strong> differentways <strong>of</strong> looking at it. But I talkto more and more deans who see tryingto provide alternative forms andformats for education beyond thebachelor’s degree as a necessarycomponent <strong>of</strong> what we do.”The other side <strong>of</strong> the coin is thatstudents choosing the traditionalroute need not limit themselves tothe traditional choices.“I think it’s important for peoplegoing into graduate school to recognizethat the people who come outwith PhDs can do many differenttypes <strong>of</strong> things,” Patterson says.“There are options in public service,in government, in corporations.There is something about the discipline<strong>of</strong> having to do unique andoriginal research that prepares you toproblem-solve in many differentareas, and that’s the real value <strong>of</strong> thePhD process.” ■5

adj. Of, relating to, or involving two or more academicdisciplines that are usually considered distinct.– The American Heritage DictionaryThe idea <strong>of</strong> lowering the barsbetween disciplines is notnew, but in many ways it’solder than the idea <strong>of</strong> separatingknowledge into disciplines inthe first place. “More and more, aswe move into the late modern age,we’ve come to realize that somehowit’s time to put the pieces backtogether.” says Earl Lewis, Dean <strong>of</strong>the <strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>School</strong>. “There havealways been little nodes within theacademy where people came togetherto wrestle with questions. You see itin scholarly journals—eight peoplepublishing a common article.”What differentiates the <strong>University</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> from its peers in thisregard is the extent to which interdisciplinarityhas been not onlyembraced but also institutionalized.The list <strong>of</strong> programs, courses and initiativesthat formally incorporatesome degree <strong>of</strong> multidisciplinaryresearch and teaching is a long one,including women’s studies, African-American studies, bioengineering,neuroscience, the American culturedoctoral program, a joint program insocial work and the social sciences, anew interdisciplinary mathematicsprogram, a master’s program infinancial engineering that straddlesthe College <strong>of</strong> Engineering and theBusiness <strong>School</strong>, the <strong>Rackham</strong>Interdisciplinary Lectures, and the<strong>Rackham</strong> Summer InterdisciplinaryInstitute.6“External reviewers always notethe range <strong>of</strong> interdisciplinarity onthis campus and how unique it is,”says Lewis. “The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Michigan</strong> probably stands at the end<strong>of</strong> the spectrum in terms <strong>of</strong> the number<strong>of</strong> faculty and even graduate studentswho are interested in someaspect <strong>of</strong> interdisciplinary training,teaching and research.”An historian himself, Lewis findsdeep roots for this phenomenon.“Part <strong>of</strong> it has to do with the makeup<strong>of</strong> the various departments where,structurally, it has been possible tohave joint appointments,” he says.“In the history department, my owndepartment, half the faculty havejoint appointments with other units,and some <strong>of</strong> us with more than one.Throughout LS&A, you see moreand more faculty with joint appointments.That increases the likelihoodthat faculty and graduate studentswill live in more than one space oncampus, and that they’ll invite colleaguesfrom outside the university toinhabit those spaces, too, as guestlecturers and so on. There’s also thissense here that we want to rewardgood ideas and opportunities thatforce faculty and students to thinkout <strong>of</strong> the box, and that also encouragesa certain kind <strong>of</strong> interdisciplinaryapproach.”Dr. Jonathan Metzl has been out <strong>of</strong>the box for some time now. Heearned a bachelor’s in English as wellas his MD in a six-year program atthe <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Missouri-KansasCity, picked up a master’s in humanitiesduring his psychiatry residencyat Stanford, then came to U-M topursue a doctorate in the Program inAmerican Culture, meanwhile seeingpatients two days a week and teachingin the women’s studies program.He was also co-director with CarolHorn, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Nursingand Women’s Studies, <strong>of</strong> the<strong>Rackham</strong> Summer InterdisciplinaryInstitute.“There’s just the atmosphere herefor creating those kinds <strong>of</strong> links,” hesays. “That’s not to say there aren’tgreat bureaucratic hurdles to getover, especially dealing with bodiesas diverse as the Medical <strong>School</strong> andLS&A, but people’s open-mindednessto that is really remarkable here,and it’s also institutionally supported,which makes a huge difference.Everybody everywhere is ‘interestedin interdisciplinarity,’ but putting astructure in place where people arerewarded for it and encouraged to doit makes it a much more valid undertaking.My sense is that, at otherinstitutions, the message is that interdisciplinarityis something you cando after you’ve gotten tenure and aresafely tucked away some place.That’s when you can dabble in otherthings. Treating it as a from-theground-upundertaking makes it amore powerful discourse and morebroadly interactive.”

The institute he co-directed bothmodeled such activity and provided aplace, like Virginia Woolf’s A Room<strong>of</strong> One’s Own, where interdisciplinarityitself could be engaged.We were going to create a systemthat was free <strong>of</strong> hierarchy, but whenwe got together in a room, peoplewere aware <strong>of</strong> who was above whomon the ladder, or who was in a disciplinethat was ‘in’ in certain crowdsor better funded. Being able toaddress those differences and talkabout them in ways that were uncomfortablesometimes lets participantsunderstand why interdisciplinary isdifficult even though it is supported.And having a realistic sense <strong>of</strong> that isconducive to creating projects orawarenesses that are more likely to besuccessful.”Elizabeth Wingrove, AssistantPr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Political Science, wasone <strong>of</strong> 19 faculty members (alongwith four postdoctoral scholars and11 graduate students) who were institutefellows. Each was asked to participatein a small working group,one <strong>of</strong> whose charges was to plan atleast one event for the <strong>University</strong> andgeneral communities. Wingrove’sgroup included representatives <strong>of</strong>English, biology, history, pharmacologyand obstetrics/gynecology, andshe describes her ongoing relationshipswith them, as well as being“part <strong>of</strong> the constituent audience” forother groups’ projects, as “sort <strong>of</strong> thegift that keeps on giving.”“A great thing that came out <strong>of</strong> itwas the opportunity to meet people Iwould not otherwise have met, and tothink <strong>of</strong> them as resources for bothteaching and research that I hadn’tknown before,” she says. “Chattingwith folks in kinesiology, nursing, thelife sciences, was an amazing thing tobe able to do, even though it was notalways easy.”But, for Wingrove and her colleagues,it was the point. “I’ve cometo realize I need structural, institutionalsupport—time, money, accessto people—to do what I thought Iwas doing fairly well on my own,”she says. “I need to talk to folks whoactually do work in medical research,who work in policy oriented work,and certainly historians. I could listthem all, but the point is that when Ifirst heard about the Institute, Ithought not only was the theme[‘Disciplinary and InterdisciplinaryApproaches to the Body: From Cellto Self’] interesting and right onpoint with what I do in my research,but this would also be an opportunityto meet these people every day andtalk to them.”One <strong>of</strong> them, a colleague <strong>of</strong>Wingrove’s in their project group, isGina Bloom, who is nearing her doctoratein English and is also in thewomen’s studies certificate program.Although it certainly wasn’t part <strong>of</strong>the Institute’s formal syllabus, “I’mhelping Liz with some editing,” shesays. “I met her through the Institute.One <strong>of</strong> the nice things that emergedfrom that is getting to meet somepeople. As a grad student, it’s sometimestough to meet pr<strong>of</strong>essors outsideyour department.”Gabriela Frank is a pianist anddoctoral candidate in music theoryand composition. She, too, wasmoved to apply for the Institute bythe opportunity to build upon theinterdisciplinary foundation shehad already laid. “One <strong>of</strong> my specialtiesis South American music,”she says, “and I did some scholarlywork with some <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>essorshere, reading a lot <strong>of</strong> the writersand poets and learning about thepolitical history <strong>of</strong> South America.I’m also very interested in howbrain science relates to music. I’mpartially deaf myself, and I’vealways wondered about Beethovenand his deafness and how thataffected his music.”Choosing the human body as atheme for an interdisciplinary instituteseems to have been a tellingstroke. “The discipline <strong>of</strong> music centersaround the body,” says Frank.“You have to be able to master yourbody to master the instrument. I wasthe only musician participating thissummer and it was wonderful. Icould draw connections to whateveryone was doing. That’s what getsinteresting, when you have peoplewho are experts in different fieldslooking at the same thing and <strong>of</strong>feringdifferent explanations. I hadopportunities to talk to very intelligentpeople at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Michigan</strong> who are not musicians. Ihad to retrain myself. I couldn’t talkabout fingerings because it wouldn’tmean anything.”But this is far from the end-gamefor the idea <strong>of</strong> disciplines. Perhapsironically, the concept <strong>of</strong> interdisciplinaritymight not only strengthenand refine disciplines but also itselftake on some <strong>of</strong> their characteristics.“I don’t believe disciplines are goingto disappear at all,” says Lewis. “Ithink interdisciplinarity will becomethe connective tissue that makes itmore sensible for disciplines to exist.“There is a training in learning abody <strong>of</strong> knowledge and a point <strong>of</strong>view that is incredibly important inentering into any academic discussion,”says Metzl. “The counterpointis that interdisciplinarity itselfbecomes disciplinary by the nature <strong>of</strong>institutions and funding. But at thesame time, if that new disciplinarystructure encourages people to thinkabout different perspectives inaddressing any number <strong>of</strong> problems,that seems like a pretty good thing.” ■7

A L U M N I P R O F I L E SPhoto by Ron MiduraResearch is a Team Sport8Research, says Kathe Derwin,is a team sport.She’s well acquainted withboth. An avid participant <strong>of</strong> bothhigh school and collegiate sports,Derwin spent her tenure as a U-Mbioengineering graduate student asa research assistant under the mentorship<strong>of</strong> Dr. Lou Soslowsky inPr<strong>of</strong>essor Steve Goldstein’sOrthopaedic Research Laboratories.A bioengineering pioneer and“an impact player” in the fieldglobally, Goldstein “built up a labwith a lot <strong>of</strong> different peoplearound,” says Derwin, who receivedher doctorate in 1998. “We interactedextensively with clinicians, scientists,and engineers. He set up amodel for bridging disciplines, andall the people he’s trained havegone on to replicate that.”Including Derwin, who is busysetting up her own lab at theCleveland Clinic Foundation toresearch how mechanical factorsinfluence the injuries, healing,remodeling, and aging <strong>of</strong> tendonsand ligaments. “I’m interested inbasic questions,” says Derwin, “butin concert with those, I would liketo do some clinical projects withour orthopaedic surgeons here.” Herinterest in such work demonstratesDerwin’s belief that “with so muchto study in this field, it will taketeams <strong>of</strong> people talking to eachother across disciplines to evenbegin to cover it all.”With an undergraduate degree inmechanical engineering from the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Massachusetts-Amherst, she briefly consideredmedical school before choosing adifferent spot on the healing artscontinuum: improving the tools thatdoctors can use to help theirpatients.What she wants to avoid, shesays, is “getting so focused on ourwork in the lab that I forget we canget a lot <strong>of</strong> valuable information out<strong>of</strong> patients. There are things thatcan be investigated, on the applicationend, right along. When you’reinvestigating basic questions, youhave the attitude that the sky’s thelimit and we just need to knowinformation, but ultimately it has tobe in an applicable form. In the

“Our ultimate goal is to replace or repair orregenerate tissue that isn’t doing well.”end, if it’s not cost-effective and insurance won’t pay for it, it’s not going tohappen.”“It doesn’t keep you from wanting to know,” she hastens to add, “butboth <strong>of</strong> those things have to happen. Part <strong>of</strong> coming out <strong>of</strong> a Goldstein labis that you’ve been taught to consider the whole continuum—from basicresearch to application.”It’s part <strong>of</strong> keeping your eye on the prize. “Our ultimate goal is toreplace or repair or regenerate tissue that isn’t doing well,” she says.“Whatever the tissue <strong>of</strong> interest might be, whether it’s bones or cartilage orligaments, the basic concepts are very similar. What matters is making animprovement to health care and people’s quality <strong>of</strong> life. What can we dobetter than what we’ve been doing? Can we engineer some sort <strong>of</strong> substituteor graft or prosthetic that the body is going to like and that will last?”Derwin is enthusiastic about the opportunities afforded her at theCleveland Clinic, both to develop a research program as well as contributeto the education <strong>of</strong> the next generation <strong>of</strong> biomedical engineers. The Cleveland Clinic’s mentorship program with cityhigh schools, as well as its affiliation with neighboring universities, will allow Derwin the opportunity to develop andteach new courses and to mentor students at various levels. “With the recent explosion <strong>of</strong> interest in this diverse field,programs everywhere are rethinking what it means to train new biomedical scientists. That will mean new courses aswell as hands-on laboratory experiences. It is exciting to be able to be a part <strong>of</strong> this growing and dynamic newdiscipline.” ■Photo by Jim Lange❒❒❒❒Please Send Me More Information About:Establishing a Trust or Bequest to Benefit <strong>Rackham</strong>’s Students and ProgramsFunding Summer Research and Travel Awards for <strong>Graduate</strong> StudentsCreating a Named Endowed FellowshipPlease add me to your mailing list to receive further information about <strong>Rackham</strong>My correct name and address is:_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Is Your Mailing Label Correct?We want to list the name <strong>of</strong> each <strong>University</strong> friend and alumnus/a correctly. But sometimes we need your help. If youare not satisfied with the way that your name and address appears on the address label <strong>of</strong> <strong>Rackham</strong> Alumni Magazine,please e-mail your corrections to rackham.alums@rackham.umich.edu/ or complete and return this form to the<strong>Rackham</strong> Development Office, 915 E. Washington, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1070.❒ Please correct my name and/or address as written aboveVisit the <strong>Rackham</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> <strong>School</strong> Web Sitehttp://www.rackham.umich.edu/9

S T U D E N T P R O F I L E S10Salvatore CerchioSalvatore Cerchio fell in loveon his 20th birthday. That’snot unusual, except that theobject <strong>of</strong> his passion was, andremains, the humpback whale.He was a junior at Tufts<strong>University</strong>, cruising the species’Caribbean breeding grounds aspart <strong>of</strong> a marine biology programfor undergraduates. “I got hooked,”he says. “I don’t know why, but Iwas seduced by it.”His ardor has since taken him tothe Moss Landing Marine Labs <strong>of</strong>San Jose State <strong>University</strong>, wherehe earned his master’s; to Hawaii,where he did research for sixyears, and to Isla Soccoro, anisland 400 miles <strong>of</strong>f the west coast<strong>of</strong> Mexico, where he is about tospend his fourth winter observinga breeding population <strong>of</strong> humpbackwhales.It also, in a sense, brought himto the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong>. “Irealized that if I wanted to do realresearch and make it my ownresearch, I needed to have a PhD,”he says. He also sought mentors inrelated but seemingly disparatefields.“My focus was always bioacoustics,”he says. “My master’swas on geographic variation inhumpback whale song, and I wantedto stretch out from the somewhatinsulated umbrella <strong>of</strong> themarine mammal world and workspecifically with pr<strong>of</strong>essors thathad experience with birds andbirdsong. Often, the marine mammalfield is kind <strong>of</strong> myopic, andcoming here and getting thesebroad diverse influences has beenexcellent for my development.”One influence was RobertPayne, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Zoology. “Bobworks on village indigobirds, aspecies which has a very interestingsong behavior, very convergentPhoto by Salvatore Cerchiowith humpback song behavior, acontinual variation <strong>of</strong> song overtime,” says Cerchio. “There areonly two species <strong>of</strong> birds known todo this, and humpback whales.Bob’s work figured prominently inmy discussion in my master’s thesis.I also wanted to work withJohn Mitani (Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<strong>of</strong> Anthropology), a primatologistdoing behavior and bioacousticswith primates.”Once at <strong>Michigan</strong>, he found it“a great place for evolution,” bothhis own and the field. “Cominghere was a real eye opener,” hesays. “What I’ve learned on thetheoretical basis <strong>of</strong> evolution andbehavior has really helped me out.I’ve also gotten involved in molecularwork. I had had no inclinationto do that but, after being here ayear, learning what facilities werehere, what opportunities I had andwhat I could do by applying

molecular techniques to my behavioralquestions, it was clear that thiswas the best thing I could do.”In 1997 Sal joined Jeff Jacobsenand Luis Medrano in a project startedover a decade ago. They spentthree months each winter on aMexican Navy base on Isla Soccoro,using crossbows to take biopsies <strong>of</strong>whales, recording their songs andphotographing them. “What we aredoing there is quite unique,” saysCerchio. “Although there exists alarger sample <strong>of</strong> biopsies from theAtlantic, something like 3,000 overtwo years, our sample in Mexico ismuch more thorough because thepopulation is much smaller. We’venow sampled 400-500 out <strong>of</strong> a thousandindividuals, and we hope tohave another 150-200 after next season.Plus there is a sighting history<strong>of</strong> individuals with behaviors thatgoes back 10 years, plus songs frommany <strong>of</strong> these animals. In a year ortwo, this sample is going to be a veritablegold mine <strong>of</strong> information, andwe should be able todo some very interestingstudies with it.There are no otherhumpback whalepopulations that willbe as thoroughlysampled, that’s forsure.”As part <strong>of</strong> Sal’sdissertation he willbe assessing paternityand male reproductivesuccess.Using the same technology utilizedin human forensic work, he creates aDNA fingerprint <strong>of</strong> skin samplesobtained from the mother and calf.By comparing a mother’s genotype toPhoto by Danielle Cholewiakher calf’s, he identifies what part <strong>of</strong>the calf’s genotype came from thefather. This is then compared to thegenetic fingerprint <strong>of</strong> all the malewhales that were sampled. If a matchis found, paternity is determined. Bycomparing many samples he will beable to discern whether humpbacksare polygynous breeders.What’s the point? There are several.First is the growth <strong>of</strong> humanknowledge: this is the first largestudy <strong>of</strong> reproductive success incetaceans. Secondly, this researchwill create a model for studyingother species.Finally, there are implications formanagement and conservation <strong>of</strong> thespecies, which was hunted almost toPhoto by Bill Woodextinction before making a comeback.Successful conservation <strong>of</strong> thehumpback whale populations musteventually derive from the work <strong>of</strong>scholars like Cerchio, lured by thewhales and their siren songs. ■Photo by Salvatore Cerchio11

S T U D E N T P R O F I L E SPhoto by Bill WoodYvette Amstelveen12Yvette Amstelveen’s current titleis Visiting Scholar at the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> <strong>School</strong><strong>of</strong> Art, the first painter ever to holdthat position. But the adjective in thattitle is as meaningful to her as thenoun: she’s going to get around.Like any serious artist, she spendsher prime time in the studio. She hasalready created considerable art in her24 years, and her pieces have beenexhibited at the National Arts Club.Likewise, her academic credentials —a bachelor <strong>of</strong> fine arts from the CooperUnion in New York City and a master<strong>of</strong> fine arts in painting from U-M —are very much in order. A native <strong>of</strong>Suriname, she moved with her familyto Miami when she was eight, speaksthree languages, and was even one <strong>of</strong>Glamour magazine’s top 10 collegewomen in 1996.Photo by Bill Wood

But perhaps her true art, or calling,is beautifying people’s lives byenabling them to do their own art,whether by teaching urban childrenin their schools or immersing herselfin the Lower Cass Corridorproject in Detroit. As one <strong>of</strong> thefew painters working on the project,her plan is to use the abandonedbuildings in the neighborhoodto create temporary art installationsas a window series <strong>of</strong> paintings.By involving residents in thedesign and implementation <strong>of</strong> theinstallations, for example, by usingtheir own patterns <strong>of</strong> clothes andfaces, she wants to help them createa “neighborhood board quilt”that will immediately beautify thearea, uplift spirits, and develop agreater sense <strong>of</strong> ownership andpride in the community.What she calls “a neighborhoodboard quilt” is a variation on hertheme for the summer <strong>of</strong> 1998,when she worked with kids — inNewark, Brooklyn, and Ann Arbor— to create neighborhood canvasquilts <strong>of</strong> their self-portraits. Lastsummer, she taught teens at theAnn Arbor Art Center, free-lancedfor Martha Stewart Living magazineand did missionary work inHungary for the Assemblies <strong>of</strong> Godchurch. For two <strong>of</strong> her years atCooper Union, she commutedevery Saturday to the Bronx to, yes,teach art to children.Her art, her community activities,and her faith are interwovenfor Amstelveen. “There’s this chapterin Isaiah that talks about providingthe wanderer with shelter,clothing the naked, looseningchains and cords when people areunder oppression, and your lightshall rise in the darkness,” she says.“When I go to Newark or ConeyIsland, I could paint beautifulthings on the outside, but if I canaffect that life, allow them to seebeauty through art, then that’s whatI want to do.” ■Photo by Yvette Amstelveen2 Timothy 2:20in the Private Collection <strong>of</strong> John WoodfordPhoto by Yvette Amstelveen13

<strong>Rackham</strong> AlumniMAGAZINEThe <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong>The Horace H. <strong>Rackham</strong><strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Graduate</strong> Studies915 East Washington StreetAnn Arbor, <strong>Michigan</strong> 48109-1070NON-PROFIT ORG.US POSTAGEPAIDANN ARBOR, MIPERMIT NO. 144The Regents <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong>David A. Brandon, Ann ArborLaurence B. Deitch, Bloomfield HillsDaniel D. Horning, Grand HavenOlivia P. Maynard, GoodrichRebecca McGowan, Ann ArborAndrea Fischer Newman, Ann ArborS. Martin Taylor, Grosse Pointe FarmsKatherine E. White, Ann ArborLee C. Bollinger (ex <strong>of</strong>ficio)The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong>, as an equal opportunity/affirmativeaction employer, complies with all applicable federal andstate laws regarding non-discrimination and affirmativeaction, including Title IX <strong>of</strong> the Education Amendments <strong>of</strong>1972 and Section 504 <strong>of</strong> the Rehabilitation Act <strong>of</strong> 1973. The<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> is committed to a policy <strong>of</strong> non-discriminationand equal opportunity for all persons regardless<strong>of</strong> race, sex, color, religion, creed, national origin or ancestry,age, marital status, sexual orientation, disability, or Vietnameraveteran status in employment, educational programs andactivities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may beaddressed to the <strong>University</strong>’s Director <strong>of</strong> Affirmative Actionand Title IX/Section 504 Coordinator, 4005 Wolverine Tower,Ann Arbor, <strong>Michigan</strong> 48109-1281, (734) 763-0235; TDD(734) 647-1388. For other <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Michigan</strong> informationcall: (734) 764-1817. AAO: 4/28/98