Urban Regeneration in Stratford, London

Urban Regeneration in Stratford, London

Urban Regeneration in Stratford, London

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

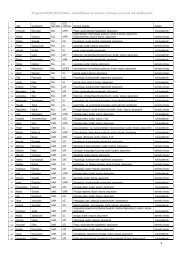

<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>, <strong>London</strong>FIGURE 1. <strong>Stratford</strong> CC: distribution between operational objectives of total estimated costs(£216 230 000)(1994) stressed that the £37.5 million of CC funds were expected to be paralleledby £200 million from other partners.Aga<strong>in</strong>st the background provided so far, it will perhaps be no surprise that the(re-)development of the transport <strong>in</strong>terchange came under operational objective1.1 and that it <strong>in</strong>cluded the redevelopment of the domestic rail station, the busstation and the refurbishment of the nearby shopp<strong>in</strong>g mall. Central governmentwas committed to this objective s<strong>in</strong>ce, alongside <strong>London</strong> Underground, <strong>London</strong>Transport and British Rail, the DoE was among the partners that would helpimprove <strong>Stratford</strong>’s image.The DoE provided land for the new bus station, which also bene ted frompartial fund<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>London</strong> Transport and soon became the agship project of<strong>Stratford</strong> CC. All <strong>in</strong>terviewees agreed on this and it is both a functional and astunn<strong>in</strong>g public build<strong>in</strong>g. Although <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the CC bid, this bus station wasnot built with CC money at all. Indeed, the means to re-build it (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g theland from the DoE) had already been l<strong>in</strong>ed up before the CC bid was even puttogether. Other projects <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the CC bid had also been on the agenda oreven <strong>in</strong> the pipel<strong>in</strong>e well before the CC opportunity came along. Land Securities,one of the members of the Promoter Group, had <strong>in</strong>tended to refurbish theshopp<strong>in</strong>g mall, for <strong>in</strong>stance, although <strong>in</strong> the event the project was delayed bydisputes over whether the market traders would be permitted to rema<strong>in</strong> (Fearnley,1999, p. 32).The <strong>in</strong>clusion of private projects already <strong>in</strong> the pipel<strong>in</strong>e gave a bonus to thedevelopers concerned. Developers with<strong>in</strong> the Promoter Group, <strong>in</strong> particular,enjoyed a ‘preferential right of entry’ <strong>in</strong>to the bid. In this sense it could beargued that the nature of the plann<strong>in</strong>g/decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g process <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>might have restricted the number of private-sector bene ciaries of two <strong>in</strong>itiatives(the CTRL campaign and CC) which, had they not been perceived as complementaryand l<strong>in</strong>ked <strong>in</strong> this way, could have bene ted a larger number of109

Simona Florio & Michael EdwardsFIGURE2. <strong>Stratford</strong> City Challenge: distribution of proposed spend<strong>in</strong>g between operational objectivesand objectives (values <strong>in</strong> £1000s). Source: <strong>Stratford</strong> City Challenge Action Plan (undated), pp. 23–27.entrepreneurs. However, because of their structure, many CC programmes havethis tendency to provide opportunities for a selected group of rms who are put<strong>in</strong> a position to capture the real-estate values <strong>in</strong> an area. In <strong>Stratford</strong>, membersof the Promoter Group might well have formed an oligopoly, but the council waspart of it and rema<strong>in</strong>ed accountable to the local electorate. Furthermore, the earlycommitment of the members of the Promoter Group helped because leveragetends to ‘follow itself’: once some <strong>in</strong>vestors become <strong>in</strong>volved others follow suit.The <strong>in</strong>clusion of projects which had previously been envisaged or started,some of which depended on public/private fund<strong>in</strong>g, helped ensure their cont<strong>in</strong>uityand enhanced their value. For <strong>in</strong>stance, the ambitious Three Mills projecthad begun as an <strong>Urban</strong> Programme/European Regional Development Fund110

<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>, <strong>London</strong>scheme (<strong>Stratford</strong> City Challenge Action Plan, undated, p. 47) and its <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong>CC gave it greater scope. Whilst it could be argued that <strong>in</strong>clusions of this typeunderm<strong>in</strong>e the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple of additionality, it is also true that us<strong>in</strong>g CC funds toattract nancial <strong>in</strong>terest to, and <strong>in</strong>crease the effectiveness of, exist<strong>in</strong>g schemeshelped keep CC with<strong>in</strong> the objectives of locally determ<strong>in</strong>ed spatial policies. Inturn, CC could give exist<strong>in</strong>g projects a new dimension. The Three Mills <strong>in</strong>itiative,whose success relied on it be<strong>in</strong>g able to attract visitors, has much better chancesif developed <strong>in</strong> conjunction with a series of other tourist-related projects <strong>in</strong>cluded<strong>in</strong> CC. In the light of this and the place-market<strong>in</strong>g exercise undertaken by CC;enlarg<strong>in</strong>g the Three Mills <strong>in</strong>itiative made sense with<strong>in</strong> CC but not before. The<strong>in</strong>clusion of Three Mills does seem to have breached the strict pr<strong>in</strong>ciple ofadditionality—<strong>in</strong> the sense that at least some of the <strong>in</strong>vestment would havehappened anyway—but there does seem to be some ‘additionality’ on the bene tside <strong>in</strong>sofar as the project ga<strong>in</strong>ed the prospect of <strong>in</strong>creased demand.Our <strong>in</strong>terpretation is that the GOL <strong>in</strong>vited a CC bid for <strong>Stratford</strong> not primarilyfor the regeneration bene ts it would br<strong>in</strong>g to local people with<strong>in</strong> ve years, butas part of a longer-term strategy for East <strong>London</strong> which would, above all, makethe area more attractive to <strong>in</strong>vestors <strong>in</strong> a later project, the CTRL. The CC wasable to l<strong>in</strong>k a series of projects which were already <strong>in</strong> the pipel<strong>in</strong>e and serve asa means further to <strong>in</strong>crease the ‘leverage’ of <strong>in</strong>vestment from other private andpublic bodies. This would transform the image of <strong>Stratford</strong> and replace it witha clean, new (or refurbished historic) physical environment with visible leisureand cultural <strong>in</strong>dustries and at least a slightly more up-market shopp<strong>in</strong>g centre.These ambitions constituted a move towards the prevail<strong>in</strong>g orthodoxy of ‘citymarket<strong>in</strong>g’. Some local bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>terests stood to ga<strong>in</strong> early bene ts whileothers would have to wait <strong>in</strong> the hope that the CTRL would arrive to valorisetheir assets.Once the bid was won and the <strong>Stratford</strong> Development Partnership (SDP) wasformed <strong>in</strong> July 1992, other <strong>in</strong>terests became <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g the actionplan. The partnership, which <strong>in</strong>cluded most of the members of the PromoterGroup except the house builders, was chaired by the director of the East <strong>London</strong>Partnership, a bus<strong>in</strong>ess organisation <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g all the major employers <strong>in</strong> thearea.Bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>terests participated and were active. The members of the <strong>Stratford</strong>Promoter Group and of the East <strong>London</strong> Partnership played a major role <strong>in</strong>gett<strong>in</strong>g a Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Forum together, which eventually elected four representativesto the SDP board. Despite the <strong>in</strong>itial bias towards some bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>terests ratherthan others, the forum gradually became an organisation through which localbus<strong>in</strong>esses took a more proactive role, though as Fearnley nds (1999, Chap.12), they tended to act as <strong>in</strong>dividuals, rather than be<strong>in</strong>g systematically representative.Creative Accountancy: Adapt<strong>in</strong>g to Government DecisionsDur<strong>in</strong>g the early stages of the CC Newham thus seemed to enjoy the bless<strong>in</strong>gof central government. With<strong>in</strong> the rst year, the southern part of the borough wasawarded Intermediate Area status under the Assisted Area programme, which111

<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>, <strong>London</strong><strong>in</strong>crease the pro tability of the project. It would clearly <strong>in</strong>crease the success ofthe Jubilee L<strong>in</strong>e Extension, the Docklands Light Railway, the Docklands, CrossRail and the East Thames corridor more generally. Ove Arup which, s<strong>in</strong>ce theearliest stages, had been <strong>in</strong> favour of the <strong>Stratford</strong> option, was one of LCR’sshareholders and had themselves been <strong>in</strong> charge of develop<strong>in</strong>g the eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>gproject. It had always been part of the Arup strategy, led by Mark Bostock,to treat the urban regeneration bene ts along the Thames estuary—and thusthe <strong>in</strong>termediate stations—as the dist<strong>in</strong>ctive cornerstone of their bid. Theyreta<strong>in</strong>ed Professor Peter Hall, who had been advisor to the Secretary of Statefor Environment and <strong>in</strong> that capacity an orig<strong>in</strong>ator of the corridor strategy.It is widely considered that these features of the LCR approach helped themto w<strong>in</strong>.While the government decision did not take <strong>in</strong>to account all the <strong>in</strong>terests ofthe <strong>Stratford</strong> Promoter Group, it would still have been likely to valorise manyof their <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>. Whether the station—if built—will bene t thelocal community or whether it will cause noth<strong>in</strong>g but <strong>in</strong>creased land prices anddisplacement, rema<strong>in</strong>s to be established. It is also not yet clear what price <strong>in</strong> stateexpenditure will have to be paid to reduce the private risk on this massive PFIproject to a level which nanciers will accept.Certa<strong>in</strong>ly the government decision was consistent with the lessons from France.The French studies undertaken to evaluate the impact of TGV (Tra<strong>in</strong> à GrandVitesse) stations have found that ‘the TGV does not automatically br<strong>in</strong>g wealthand prosperity to a region’ and that there is no simple cause–effect relationshipbetween transport <strong>in</strong>vestment and bus<strong>in</strong>ess growth (Turner, 1996, p. 35).The studies reviewed by Turner showed that TGV stations can act as a catalystfor growth ‘by creat<strong>in</strong>g an opportunity for plann<strong>in</strong>g policies and developmentprojects to be implemented <strong>in</strong> order to capitalise on the arrival of the high speedtra<strong>in</strong>s’ (Turner, 1996, p. 36). The notion of an automatic growth effect wasrejected and replaced by the concept that the stations can have a ‘structur<strong>in</strong>g’,‘opportunity’ or ‘permissive’ effect. In particular, the policies put <strong>in</strong> place bylocal participants were found to be of central importance <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g theactual extent of any regeneration effect of the stations. (See Table 4).)In <strong>Stratford</strong> the abundance of town plann<strong>in</strong>g and development operations werenot aimed at generat<strong>in</strong>g immediate monetary ga<strong>in</strong>s to the agents <strong>in</strong>volved, butrepresented a more long-term view. The image of the locality was enhanced, itsexist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>frastructure was upgraded and promoted, ancillary structures werebuilt and local passenger services were modi ed and improved. All the <strong>in</strong>gredientslisted <strong>in</strong> Table 4 are present.The CC <strong>in</strong>itiative <strong>in</strong> particular was primarily bene cial at a time the governmentwas unwill<strong>in</strong>g to provide nancial assistance to development of the<strong>in</strong>ternational rail l<strong>in</strong>k. The promotion of leisure venues and some tourism-relatedactivities 3 was a great achievement of the CC and an important aim of SRB<strong>in</strong>itiatives. In summary, the process which led to the selection of <strong>Stratford</strong> as thelocation of the new station seems to have <strong>in</strong>deed acted as a catalyst creat<strong>in</strong>g anopportunity for the implementation of creative plann<strong>in</strong>g and development <strong>in</strong>itiatives.Thus, the orchestration of development around the prospective station doesseem to have had a ‘structur<strong>in</strong>g’, ‘opportunity’ or ‘permissive’ effect.115

Simona Florio & Michael EdwardsTABLE 4. Elements that re-enforced the regenerat<strong>in</strong>g effects ofTGV stations <strong>in</strong> France· Presence of universities and research <strong>in</strong>stitutes· High-quality urban fabric· Creation of development zones· Provision of start-up facilities for rms· F<strong>in</strong>ancial or tax <strong>in</strong>centives· Promotion of leisure and tourism· Town plann<strong>in</strong>g and property development operations· Promotion of the local town, the region and <strong>in</strong>frastructure· Construction of ancillary structure· Modi cation of local passenger services· Frequency of railway services· Construction of highway systemsSource: Turner (1996, from French M<strong>in</strong>istry of Transport sourcesand from her own research).The effects of any actual CTRL development are still <strong>in</strong> the future and thusunclear, but there is a widespread optimism that, because CC and SRB fundswere used to this end, regeneration will occur regardless. It was even argued bya staff member of the SDP that ‘<strong>Stratford</strong> has very good transport connectionsand, even without the <strong>in</strong>ternational station, it will do just as well’.So, whilst it was central government which took the decision that a CTRLstation should be located <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>, local actors do seem to have <strong>in</strong> uencedthat decision. Had local <strong>in</strong>terest groups not taken such an active role, they wouldnot have embarked on all the <strong>in</strong>itiatives which generated these ‘structur<strong>in</strong>g’,‘opportunity’ or ‘permissive’ effects. All this suggests that, even with<strong>in</strong> a systemof governance which restricts the power of local authorities, locally determ<strong>in</strong>edspatial policy agendas can rema<strong>in</strong> important. Whilst it is true that CC partnershipsare not accountable to local electorates, there still is a lot that localauthorities can do to ensure that their actions comply with locally determ<strong>in</strong>edspatial policy and aspirations, at least where local priorities are rst brought <strong>in</strong>tol<strong>in</strong>e with those of central government.ConclusionsThe shift <strong>in</strong> British urban policies <strong>in</strong> the early 1990s addressed two majorcriticisms of 1980s’ experience. Critics from the left and centre were concernedthat local government had been severely weakened and the CC ‘partnership’approach was presented as a means to re-empower local government. Right-w<strong>in</strong>gideologists had opposed the massive—almost Keynesian—state spend<strong>in</strong>g whichhad paradoxically been entailed <strong>in</strong> the property-oriented activities of the UDCs.The PFI was launched as a means to make good the dis-<strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> publicservices, and to do so <strong>in</strong> a form faithful to the ideological taboo aga<strong>in</strong>st stateexpenditure. The easy privatisation of utilities had been completed; nowpro table <strong>in</strong>vestment opportunities were to be created <strong>in</strong> schools, prisons, social116

<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>, <strong>London</strong>hous<strong>in</strong>g, roads and railways, all the subject of strong demands for modernisationfrom both citizens and bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>terests. At the time, government seemed to bemov<strong>in</strong>g a bit to the left, a bit to the right. The <strong>Stratford</strong> analysis now enables usto see some of the outcomes and <strong>in</strong>terpret what has been happen<strong>in</strong>g. It is a useful<strong>in</strong>stance because so many of the strands of 1980s’ and 1990s’ policy arerepresented <strong>in</strong> it.Partnerships of the type analysed here do <strong>in</strong>deed seem to have returned somepower to local government, albeit with some loss of transparency and accountability.But this has not been a ‘re-empowerment’ <strong>in</strong> the sense of a return of theirprevious power: councils lack the resources to resume their pre-1980 roles aslarge-scale providers of social facilities and hous<strong>in</strong>g from their own dependableresources. Neither has it been a return of power to the radicals of the early1980s: they had been discouraged or outvoted or sidel<strong>in</strong>ed. Instead localgovernment has ga<strong>in</strong>ed some new powers, to orchestrate and lead local <strong>in</strong>itiativeswhich can harness public and private resources on certa<strong>in</strong> conditions. Thekey conditions are that the <strong>in</strong>itiatives conform with the priorities of private<strong>in</strong>vestors on the one hand and of the ever-more-powerful regional governmentof ces on the other. The pursuit of private <strong>in</strong>vestment through ‘leverage’ securedby local competition for small public funds can be targeted at localities wheregovernment judges there to be need or opportunity.Newham Council has been good at play<strong>in</strong>g this new game. The present papershows how the council, under its ‘modernis<strong>in</strong>g’ leadership, was able to act verycreatively, shap<strong>in</strong>g national policy on the route of the CTRL, weav<strong>in</strong>g strands ofBritish government, EU and other fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to a substantial rope with which tohoist its town centre to prom<strong>in</strong>ence. An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g sub-plot is that the <strong>Stratford</strong>Development Partnership, set up to run the CC, has become so renowned forwrit<strong>in</strong>g and ‘deliver<strong>in</strong>g’ urban regeneration projects that it is now runn<strong>in</strong>g rescueand management services <strong>in</strong> many other <strong>London</strong> regeneration projects: themanagement of ‘regeneration’ itself becomes a growth sector.We found little evidence, however, of a re<strong>in</strong>vigorated local democracy. Bothgrass-roots and electoral politics <strong>in</strong> Newham had apparently been fairly quiescent<strong>in</strong> the 1970s and 1980s, and none of our <strong>in</strong>formants suggested that muchhas changed, either <strong>in</strong> ‘community’ activity or <strong>in</strong> formal representative democracy.Overt local con ict seems to have been largely absent and we suggest that thecompetition for space, the tendencies to gentri cation and displacement, and thecon icts between residents and big capital (all of which characterise regenerationaround the centre of <strong>London</strong>) are still largely absent. In <strong>Stratford</strong> we nd onlyweak forms of this con ict, for example the resistance of market stallholders toejection from the re-vamped mall. It is quite plausible that there should be lessscope for con icts <strong>in</strong> such an essentially low-<strong>in</strong>come and low-value part of thecity with so much unused space.An important part of the current settlement is that local authorities’ statutoryplans, albeit modi ed to be more bus<strong>in</strong>ess-friendly , are restored as the ma<strong>in</strong>guide to what developments will be permitted—and the property market ourishes on these little certa<strong>in</strong>ties. We have seen how the spatial developmentprospects for a wide area east of <strong>London</strong> have been composed <strong>in</strong> the govern-117

Simona Florio & Michael Edwardsment’s East Thames Corridor (Thames Gateway) strategy. This strategy representsa creative response to strong economic and demographic pressures whichalso serves to valorise important development sites with<strong>in</strong> and beyond <strong>London</strong>.Its implementation is, however, fraught with problems. It has never beenproposed to provide the essential <strong>in</strong>frastructure through a French-style state<strong>in</strong>vestment paid for through gross domestic product growth or through sale ofstate-owned land. Instead the key <strong>in</strong>frastructure (the CTRL and its paralleldomestic service) is to be nanced through the PFI. The railway is veryexpensive and most of the result<strong>in</strong>g land-value <strong>in</strong>creases will ow to privateowners. Thus private <strong>in</strong>vestors can only be expected to nance the railway witha large state subvention plus the prospect of development pro ts on the smallareas of land <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the PFI package—notably land around the station sites.Newham’s spatial development strategy has thus been conditioned—and may beforever frustrated—by the needs not of local bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong>terests but of centralgovernment’s attempts to woo major <strong>in</strong>vestors for the PFI. Some local bus<strong>in</strong>ess<strong>in</strong>terests have been effectively subord<strong>in</strong>ated to more powerful forces.Most of the detailed analysis <strong>in</strong> this paper has exam<strong>in</strong>ed how the series ofw<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g local bids for CC and SRB funds have contributed to the transformationof <strong>Stratford</strong>’s image as a necessary pre-condition for secur<strong>in</strong>g the developmentof the CTRL on these terms.The unfold<strong>in</strong>g events at <strong>Stratford</strong> can thus be seen as quite purposeful.However, there is no signi cant evidence that the much-criticised ‘property-led’approach of the UDCs was replaced by a more holistic or comprehensiveapproach to deprivation. Successive bids for funds were prepared with m<strong>in</strong>imalanalysis of the causation of local problems and with only a rather tokenconsultation with ‘the community’. The ma<strong>in</strong> successes have been <strong>in</strong> gett<strong>in</strong>g landdeveloped and build<strong>in</strong>gs completed, as <strong>in</strong> Docklands. However, the developmentsare of a different k<strong>in</strong>d: <strong>in</strong>frastructure and improvements to shoppp<strong>in</strong>g andother services, all of which which cater for the locality, even if they areconceived to attract <strong>in</strong>vestors.More profound structural changes to economic and social relations havelargely eluded the <strong>Stratford</strong> projects. It may well be that deprived residents willbene t from new jobs or from Newham’s improved scal position. But there isno sign that the mechanisms which exclude poorer <strong>London</strong>ers from labour-marketsuccess have been either identi ed or effectively addressed. No evidence hasbeen advanced that conditions <strong>in</strong> Newham are signi cantly better than they werea decade ago. Five-year programmes are unlikely to transform the Britisheducation system, the class system or the recruitment practices of employers.AcknowledgementsThis paper is based upon the published documents listed <strong>in</strong> the references andon a series of extended <strong>in</strong>terviews with people who had been key players <strong>in</strong> thestory. The authors are extremely grateful to the follow<strong>in</strong>g who were k<strong>in</strong>d enoughto be <strong>in</strong>terviewed <strong>in</strong> connection with this research. The authors have used the<strong>in</strong>formation given <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g the paper (though without <strong>in</strong>dividual attributions )and are responsible for the <strong>in</strong>terpretations: Bob Colenutt (on various occasions),118

<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Stratford</strong>, <strong>London</strong>Rebecca Fearnley, Marlon Dwyer, Drew Stevenson, Philip Morris, Steve Jacobs,Councillor Stephen Timms (now MP) and Di Kershaw. The authors are gratefulto Bob Colenutt and to three anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlierdrafts.Notes1. The literature is well known and <strong>in</strong>cludes Audit Commission (1991), Loftman and Nev<strong>in</strong> (1992), NCVO(1993), Colquhoun (1994), Mawson et al. (1995), Robson (1995), Aaronovich & Agethangelou (1997),Schaechter & Loftman (1998), Imrie & Thomas (1999) and Colenutt (2000). Space precludes a full reviewhere.2. The company, <strong>Stratford</strong> Development Partnership, clearly has developed a strong culture which ndscommon ground between the council, some private <strong>in</strong>terests and central government. It is so highly regardedby the GOL that it has been encouraged or permitted to act for a number of other projects <strong>in</strong> East and Central<strong>London</strong>: they know how to write proposals and get the funds, they can run the projects and deliver the‘outputs’. They have the ear of the GOL and seem to do their job effectively.3. However, the <strong>Stratford</strong> Hotel and conference centre foreseen <strong>in</strong> the CC Action Plan, which was to <strong>in</strong>cludean 80-bedroom hotel and eight new retail units, was expected not to be built.ReferencesAaronovitch, S. & Agethangelou, T. (Eds) (1997) <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong>: Evaluation as a Tool for PolicyDevelopment (<strong>London</strong>, Local Economic Policy Unit, South Bank University).Audit Commission (1991) The <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong> Experience: Observations from Local Value-for-MoneyAudits (<strong>London</strong>, The Audit Commission).Bailey, N., Barker, A. & MacDonald, K. (1995) Partnership Agencies <strong>in</strong> British <strong>Urban</strong> Policy (<strong>London</strong>, UCLPress).Colenutt, B. (1990) Politics, not partnerships, <strong>in</strong>: J. Montgomery & A. Thornley (Eds) Radical Plann<strong>in</strong>gInitiatives, pp. 312–320 (<strong>London</strong>, Gower).Colenutt, B. (2000) New Deal or no deal for people-based regeneration?, <strong>in</strong>: R. Imrie & H. Thomas (Eds)British <strong>Urban</strong> Policy, pp. 233–245 (<strong>London</strong>, Chapman).Colquhoun, I. (1995) <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong>: An International Perspective (<strong>London</strong>, Batsford).Department of Transport (1994) Mawh<strong>in</strong>ney launches Channel Tunnel Rail L<strong>in</strong>k competition. Press Notice No.325, 31 August (<strong>London</strong>, Department of Transport Press of ce).Department of Transport (1996) Sir George Young announces w<strong>in</strong>ners of Channel Tunnel Rail L<strong>in</strong>kCompetition. Press Notice No. 64, 29 February (<strong>London</strong>, Department of Transport Press Of ce).Edwards, M. (1992) A microcosm: redevelopment proposals at K<strong>in</strong>g’s Cross, <strong>in</strong>: A. Thornley (Ed.) The Crisisof <strong>London</strong>, pp. 163–184 (<strong>London</strong>, Routledge).Fearnley, R. (1995) <strong>Stratford</strong> City Challenge Evaluation. Year 2. CIS commentary No. 51 (<strong>London</strong>, Centre forInstitutional studies, University of East <strong>London</strong>).Fearnley, R. (1999) <strong>Stratford</strong> City Challenge: F<strong>in</strong>al Evaluation (<strong>London</strong>, University of East <strong>London</strong>).Florio, S. & Brownill, S. (2000) Whatever happened to criticism—<strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g the LDDC’s obituary, City, pp.53–64.Foster, J. (1999) Docklands: Cultures <strong>in</strong> Con ict, Worlds <strong>in</strong> Collision (<strong>London</strong>, UCL Press).Imrie, R. & Thomas, H. (1999) <strong>Urban</strong> Policy, modernisation and the regeneration of Cardiff Bay, <strong>in</strong>: R. Imrie& H. Thomas (Eds) British <strong>Urban</strong> Policy: An Evaluation of the UDCs, pp. 74–88 (<strong>London</strong>, Sage).Llewellyn Davies & Tym, R. (1993) East Thames Corridor: A Study of Development Capacity and PotentialPrepared for the DOE (<strong>London</strong>, HMSO).Loftman, P. & Nev<strong>in</strong>, B. (1992) <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Regeneration</strong> and Social Equity: A Case Study of Birm<strong>in</strong>gham1986–1992. Research paper 8. (Birm<strong>in</strong>gham, Faculty of the Built Environment, University of CentralEngland).<strong>London</strong> Borough of Newham (1985) <strong>Stratford</strong> and Cann<strong>in</strong>g Town Distict Plan (<strong>London</strong>, Department ofEnvironmental Plann<strong>in</strong>g, Plann<strong>in</strong>g Division, <strong>London</strong> Borough of Newham).<strong>London</strong> Borough of Newham (1991), Newham Unitary Development Plan (<strong>London</strong>, Department of EnvironmentalPlann<strong>in</strong>g, Plann<strong>in</strong>g Division, <strong>London</strong> Borough of Newham).119

Simona Florio & Michael Edwards<strong>London</strong> Borough of Newham (1994) Annual Report (<strong>London</strong>, <strong>London</strong> Borough of Newham).<strong>London</strong> & Cont<strong>in</strong>ental Railways (1996) Press release, 29 February.Mawson, J., Beazley, M., Bur tt, A., Coll<strong>in</strong>ge, C., Hall, C., Loftman, P., Nev<strong>in</strong>, B., Srbljan<strong>in</strong>, A. & Tilson,B. (1995) The S<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>Regeneration</strong> Budget: The Stocktake (Birm<strong>in</strong>gham, School of Public Policy,University of Birm<strong>in</strong>gham).National Council for Voluntary Organisations (1993) Community Involvement <strong>in</strong> City Challenge. A policyreport of the Economic Policy Team of the National Council for Voluntary Organisations (<strong>London</strong>,National Council for Voluntary Organisations).Newham News (1992) January.Newham News (1993) The <strong>Stratford</strong> Promoter Group bid, January.Newham News (1994) May.Page, M. W. (1996) Locality, hous<strong>in</strong>g production and the local state, Environment and Plann<strong>in</strong>g D: Societyand Space, 14(2), pp. 181–202.Robson, B. (1995) Assess<strong>in</strong>g the impact of urban policy, Regenerat<strong>in</strong>g Cities, 7, p. 40.Schaechter, J. & Loftman, P. (1998) Unequal partners. Partnership agencies and social regeneration, City, 8,pp. 105–116.Stevenson, D. (1994) Partnerships and the new sub-regions needed for resource bidd<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>: Edwards, M. &Ryser, J. (Eds) Bidd<strong>in</strong>g for the S<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>Regeneration</strong> Budget. Sem<strong>in</strong>ar proceed<strong>in</strong>gs, pp. 44–48 (<strong>London</strong>,Bartlett, UCL).<strong>Stratford</strong> City Challenge Action Plan (undated) Change at <strong>Stratford</strong> (Newham, <strong>Stratford</strong> DevelopmentPartnership).<strong>Stratford</strong> City Challenge Bid (undated) Submission document (Newham).<strong>Stratford</strong> Promoter Group (1993) The Case of <strong>Stratford</strong> International Station. Cover<strong>in</strong>g letter to submissionbid, 29 October (Newham, <strong>Stratford</strong> Promoter Group).Smithers, R. (1994a) Channel l<strong>in</strong>k station named, The Guardian, 1 September.Smithers, R. (1994b) Rumbold adds to Ebbs eet scepticism, The Guardian, 29 October.Thornley, A. (Ed.) (1992) The Crisis of <strong>London</strong> (<strong>London</strong>, Routledge).Thornley, A. (1993) <strong>Urban</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g under Thatcherism (<strong>London</strong>, Routledge).Turner, V. (1996) Marne-la-Valée: ville nouvelle, ville à grande vitesse, MSc EPDP dissertation (<strong>London</strong>,Bartlett, UCL).Union Railways (1996) Press release.120