They can because they think they can.pdf - CTE - Online Learning ...

They can because they think they can.pdf - CTE - Online Learning ...

They can because they think they can.pdf - CTE - Online Learning ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

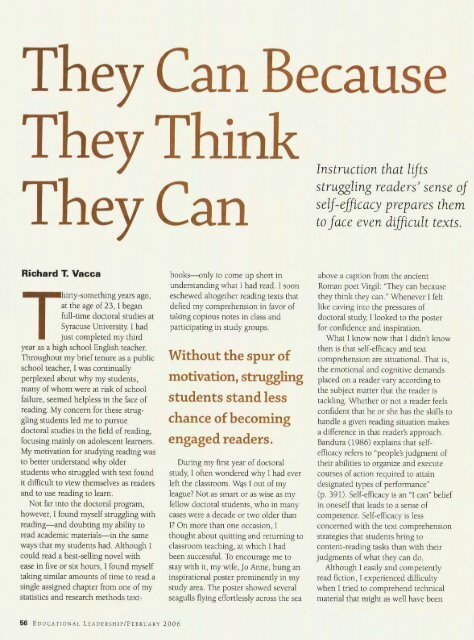

<strong>They</strong> Can Because<strong>They</strong> Think<strong>They</strong> CanInstruction that liftsstruggling readers' sense ofself-efficacy prepares themto face even difficult texts.Richard T. Vaccaat the age of 23, 1 beganfull-time Shrys m tigyears doctoral studies ago, atSyracuse University. I hadT just completed my thirdyear as a high school English teacher.Throughout my brief tenure as a publicschool teacher, I was continuallyperplexed about why my students,many of whom were at risk of schoolfailure, seemed helpless in the face ofreading. My concern for these strugglingstudents led me to pursuedoctoral studies in the field of reading,focusing mainly on adolescent learners.My motivation for studying reading wasto better understand why olderstudents who struggled with text foundit difficult to view themselves as readersand to use reading to learn.Not far into the doctoral program,however, I found myself struggling withreading-and doubting my ability toread academic materials-in the sameways that my students had. Although Icould read a best-selling novel withease in five or six hours, I found myselftaking similar amounts of time to read asingle assigned chapter from one of mystatistics and research methods textbooks-onlyto come up short inunderstanding what I had read. I sooneschewed altogether reading texts thatdefied my comprehension in favor oftaking copious notes in class andparticipating in study groups.Without the spur ofmotivation, strugglingstudents stand lesschance of becomingengaged readers.During my first year of doctoralstudy I often wondered why I had everleft the classroom. W4s I out of myleague? Not as smart or as wise as myfellow doctoral students, who in manycases were a decade or two older thanI? On more than one occasion, Ithought about quitting and returning toclassroom teaching, at which I hadbeen successful. To encourage me tostay with it, my wife, Jo Anne, hung aninspirational poster prominently in mystudy area. The poster showed severalseagulls flying effortlessly across the seaabove a caption from the ancientRoman poet Virgil: "<strong>They</strong> <strong>can</strong> <strong>because</strong><strong>they</strong> <strong>think</strong> <strong>they</strong> <strong>can</strong>." Whenever I feltlike caving into the pressures ofdoctoral study, I looked to the posterfor confidence and inspiration.What I know now that I didn't knowthen is that self-efficacy and textcomprehension are situational. That is,the emotional and cognitive demandsplaced on a reader vary according tothe subject matter that the reader istackling. Whether or not a reader feelsconfident that he or she has the skills tohandle a given reading situation makesa difference in that reader's approach.Bandura (1986) explains that selfefficacyrefers to "people's judgment oftheir abilities to organize and executecourses of action required to attaindesignated types of performance"(p. 391). Self-efficacy is an "I <strong>can</strong>" beliefin oneself that leads to a sense ofcompetence. Self-efficacy is lessconcerned with the text comprehensionstrategies that students bring tocontent-reading tasks than with theirjudgments of what <strong>they</strong> <strong>can</strong> do.Although I easily and competentlyread fiction, I experienced difficultywhen I tried to comprehend technicalmaterial that might as well have been56 EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP/FEBRUARY 2006

written in a foreign language. I lackedthe confidence to read statistical textand research methodology at the beginningof my doctoral program, and thatlack of confidence threatened both mymotivation and my reading comprehension.Over time, I developed competencein reading these kinds of textsandconfidence in my ability to do so.Explicit instruction in reading comprehensionstrategies is essential tobringing struggling readers along. Butwithout a sense of competence,students will have a hard time digginginto enough positive reading experiencesto get the practice <strong>they</strong>'ll need tointernalize those strategies.Self-Efficacy andText ComprehensionUncertainty, coupled with lack ofstrategy, subverts too many strugglingreaders' ability to comprehend text.When middle or high school studentsapproach content-area reading assignments,some feel confident in theirability to pull off the task, but manyothers feel clueless about how tosuccessfully comprehend the text.Self-efficacy and text comprehensionare not only situational but also interrelated,and motivation is related to bothelements. If students believe, forexample, that <strong>they</strong> have a good chanceof succeeding at understanding what<strong>they</strong> are reading, then <strong>they</strong> are likely tobe more motivated to engage in readingand to persevere. Guthrie and Wigfield(2000) call for "a reading engagementmodel" that underscores the importanceof both increasing students' motivationto read and providing instructionin comprehension strategies andsocial interaction in the classroom.Without the spur of motivation, strugglingstudents stand less chance ofbecoming engaged readers.Strategies to IncreaseEngagementOne of the realities facing teachersacross all content areas today is thatmany students either read at a superficiallevel to answer homework questionsor find ways to circumventreading altogether. When I wastempted to take the avoidance path as agraduate student, I was fortunate tohave the family support and personalmotivation to keep me going and helpme develop workable strategies. Educatorsneed to give struggling readers thesame kind of boost by increasing theirmotivation to comprehend texts andintroducing students to a variety ofcomprehension strategies. Effectiveresearch-based comprehension strategiesinclude question generation, questionansweringroutines, comprehensionmonitoring, cooperative learning,summarization, graphic organizers, andfamiliarity with different text structures.To use any comprehension strategyeffectively, students need to focus theirattention on the reading task at hand.Simply assigning them a text for homeworkor in-class discussion won'tnecessarily guarantee that <strong>they</strong> willattend to the reading task with thefocus needed for effective comprehension.In fact, the opposite may be thecase. Students with low self-efficacy <strong>can</strong>easily become discouraged with thetask before <strong>they</strong> even start if their onlymotivation is to fulfill an assignment.Once into reading, these students'minds will quickly wander from thereading task if the text holds noinherent interest for them, if <strong>they</strong> readwithout purpose, or if <strong>they</strong> fail to makepersonal connections with the materialas <strong>they</strong> are reading. If students lackengagement with texts, <strong>they</strong> areunlikely to tap into whatever readingstrengths and strategies <strong>they</strong> possess.ASSOCIATION FOR SUPERVISION AND CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT 57

What teachers do before assigningstudents a text is an integral part ofinstruction in content-centered literacylessons. Teachers are in a better positionto increase students' motivation if<strong>they</strong> activate learners' backgroundknowledge and get students <strong>think</strong>ingabout the topic before <strong>they</strong> begin toread. Prereading instructional strategiesoften involve arousing curiosity aboutthe topic, evoking predictions andcreating anticipation for reading,presenting problems to be solvedthrough reading, or eliciting studentgeneratedquestions about the materialbefore assigning a particular text (Vacca& Vacca, 2005).Using Real-Life MotivatorsName That SnakeA personal anecdote <strong>can</strong> be a powerfulinstructional tool that establishes apersonal context in which readers <strong>can</strong>interact with new information. Forexample, a middle school scienceteacher I taught in one of my graduateleveleducation courses used a real-lifesituation that he had encountered topique his students' interest beforeassigning research about snakes as partof a unit on reptiles. While looking fora parking spot, the teacher had noticeda flyer posted on a telephone pole,readingSNAKE FOUNDSUNDAY, OCTOBER 24ON INDIANA AVENUEPLEASE CALL 262-9415DESCRIBE TO CLAIMThe science teacher retrieved theflyer to use as a motivational tool in hisstudents' study of snakes. Before heeven assigned reading materials, theteacher recounted to students how hehad come across the flyer en route to acollege football game. He arousedstudents' curiosity with this simpleanecdote. Next, he elicited studentquestions by establishing a hypotheticalproblem to be solved. He asked theConnecting readingmaterial to students'lives activatesstudent motivation.students, "If you were to make a telephonecall in response to the flyer, whatwould you need to know about the lostsnake in order to describe it and claimit?" This led to discussion in whichstudents raised such questions as, "Is ita pet snake or a wild snake?" and"What does the snake look like?" Theclass decided that the snake had to besomeones pet, especially if it had beenfound near a college campus in anurban area.To tap students' background knowledge,the teacher then started a discussionabout what kinds of snakes makegood pets. Once students were curiousand motivated to solve the problem,<strong>they</strong> formed collaborative groups, eachconducting a purposeful search forinformation about various kinds of pet@snakes. The teacher, working with theschool librarian, had gathered togethervarious resource books about snakesfor the student teams to use in theirresearch. In addition to books, studentteams were encouraged to use theInternet to find information about petsnakes. After researching the topic,each team had to choose one kind ofsnake to describe in detail. The teacherthen had students role-play the telephoneconversation that might occur if<strong>they</strong> called to claim the snake.This science teacher followed areading engagement model to involvestudents in an active, purposeful, andthoughtful search for text informationabout snakes. From a strategy perspective,students were engaged in <strong>think</strong>ingabout texts before, during, and afterreading.Creating Hooks to Students' LivesUsing an analogy that connects readingmaterial to students' lives is anotherway to activate student motivation.Mathiason (1989) suggested that analogiesprovide "cognitive hooks" onwhich to hang new ideas. These hookshelp students look at their past experiencesand existing knowledge in newways.For example, consider a high schoolEnglish teacher who is beginning a uniton Shakespeare by introducing studentsto the importance of theater in the livesof people during Shakespeare's time.The teacher might make an analogybetween modern moviegoers andtheatergoers in the Elizabethan era.The teacher might lead into thisanalogy with a general question like"What did you do this weekend forfun?" or "Did anyone see a movie thisweekend?" and follow up with questionsto determine why students wentto see a given movie at the local theateror rented a popular DVD. Responsesundoubtedly will vary from "Becausewe heard it was funny" to "Everyoneelse was going." The discussion stem-58 EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP/FEBRUARY 2006

ming from these questions will helpstudents recognize that today's moviesaffect their lives in ways similar to theway plays affected people's lives 500 ormore years ago. The class might reflecton key differences in customs: Forexample, people in Elizabethan daysgathered outside their homes for liveentertainment, whereas movie loverstoday <strong>can</strong> watch movies or even filmedplays at home. To complete the discussion,the teacher might show a brief clipfrom the movie Shakespeare in Love togive students a sense of Elizabethan lifeand a visual image of the Globe Theatre.Flight ConditionsTo paraphrase Virgil, students <strong>can</strong> readpotentially difficult text if <strong>they</strong> <strong>think</strong><strong>they</strong> <strong>can</strong>. When students feel certainthat <strong>they</strong> <strong>can</strong> master the material <strong>they</strong>are facing, even those students forwhom reading rarely comes smoothlystand a better chance at achieving thatmastery. Reading may never become aseffortless for us as flying across the sea isfor seagulls. But if we provide situationsin which students feel both motivatedand competent, even daunting texts willhave no chance of grounding them. MReferencesBandura, A. (1986). Social foundations ofthought and action: A social cognitive theory.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000).Engagement and motivation in reading.In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D.Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook forreading research (Vol. 3, pp. 403-422).Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Mathiason, C. (1989). Activating studentinterest in content area reading. Journal ofReading, 33, 170-176.Vacca, R. T., & Vacca, J. L. (2005). Contentarea reading: Literacy and learning acrossthe curriculum, 8/e. Boston: Allyn andBacon.Richard T. Vacca is Past President ofthe International Reading Associationand Professor Emeritus of LiteracyEducation at Kent State University;rvacca@kent.edu.Tachers •he across country have already discovered thesediagnostic tools for reading and math that inform instruction sostudents <strong>can</strong> excel on required exams. No assessments are better forproviding formative and surniative information that help monitoradequate yearly progress.Because GRADE and GM E give accurate, easy-to-read resultsat the indivi class, a school level, there is more time forplanning, gro ing, and ntion-not to mention teaching.Easy to adminiter, score, report, our group assessments arealso affordably priced. Call us visit our Website today for moreinformation!Let AGS Publishing score, report, analyze, and manage test data foryou. Contact us for details.* Your vision.Our resources.P U B L I S H I N G800-328-2560www.agsnet.com© 2005 AGS Publishing. AGS Publishing is a trademark and trade name of Ameri<strong>can</strong> Guidan service, Ict. 507-241.03ASSOCIATION FOR SUPERVISION AND CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT 59

COPYRIGHT INFORMATIONTITLE: <strong>They</strong> Can Because <strong>They</strong> Think <strong>They</strong> CanSOURCE: Educational Leadership 63 no5 F 2006PAGE(S): 56-9WN: 0603203461010The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and itis reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article inviolation of the copyright is prohibited.Copyright 1982-2006 The H.W. Wilson Company. All rights reserved.