View PDF - Philadelphia Folklore Project

View PDF - Philadelphia Folklore Project

View PDF - Philadelphia Folklore Project

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

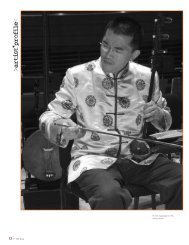

S T O R I E S T O L I V E B YF O L K A R T S O F S O C I A L C H A N G E E X H I B I T I O NRight: Tror sao, twostringedviolin by PeangKoung, 1980s. Far Right:a case of objects associatedwith “stories to liveby,” including a pennantfrom the 1963March on Washington,a “Save Chinatown” t-shirt, artifacts from thePowelton “FBI StreetFair,” the first Take BackThe Night March, thefirst issue of the Ladder,and more. Photo:Will BrownLeft: Father Paul Washington’s 1968 leatherboundcalendar. Below: Objects included in“Stories to Live By” section: alternativepapers, perspectives on Frank Rizzo, a t-shirt“Welcome to <strong>Philadelphia</strong>” on the MOVEbombing. Photos: Will BrownWords to Live By“There comes a time when we must act, not because it istraditional, not because it’s acceptable, but becauseconscience says that it is right.”“His instrument is his spirit”“The tror sao is one of the main instruments forplaying the music for Cambodian weddings. In alot of the music, especially the wedding, the trorsao would lead the music and then other musicianswould follow that. When my dad used toplay, he would be the tror sao. And the wholegroup used to be our family—seven people, playingtakhé, khim, tror ou, drum and singing. Wayat the beginning, my brother Koung Khom playedthe drums. My sister Leap played the khim,along with me—she would also help sing. I wouldplay the takhé and my sister Lisa would alsoplay the takhé. Sometimes we would changearound. My brother Sipo would play a tror ou, orswitch with my father. My father still plays thetror, with a new group that he helped organize.We don’t play together as a family any more. Wesurvived the Khmer Rouge, but my brother diedhere from cancer. My sister Leap was really talented, creative and outgoing. She was caring toothers. She was killed on June 30, 1996 as abystander in a violent shooting spree in thecommunity. The reason I name both the artsand the tragedies is that you have to carry onthe art-it helps you remember at least. Andsometimes art can help you forget and sometimesforgive. So no matter what happens orwhat kind of tragedies my father went through,he wouldn’t give his music up. Although it is hard.Sometimes you feel you are playing in pain,because usually you used to be in a group withall of the family and now my father is in a groupwithout us. For me, it is painful. I couldn’t handleit, but for him he is into it and he really cherishesthe music, no matter what. It is like breathingfor him. It’s like a weapon to protect yourself.His instrument is his spirit.”–Leendavy Koung (daughter of the artist)Plenty of history is stored inthe memories and keepsakes ofthose who lived through bothlegendary and little-knownstruggles for justice and freedom.The everyday objectsgathered in the final section of“Folk Arts of Social Change”were associated with significantexperiences. Like thehand-made objects in the openingsection, their meanings,messages and uses are keptalive by their custodians; suchmeanings are not always readilyapparent.The objects included are physicalevidence of important stories,and of the community thatemerges from the kitchentables, the streets, and thechurch basements where workfor social change began andcontinues. Each of the artifactsreflects aspects of the identityand perspective of the personwho saved it, as well as thehistory of a family, a community,or a political movement.Justice and equity live both inthe stories that animate theseobjects and in the debates anddisagreements that they provoke.Each of these objectsholds many stories for itsowner. In the exhibition, wetold some of these stories; othersremain unsaid.Stories associated with theseand other objects of memoryelaborate universal themes:epic sagas of conflicts betweengood and evil, the exploits ofclever tricksters and venerablesages, tales of great risks andof how people have “paid theprice.” There are coming of agestories, and stories of how peoplehave served as witnessesand actors, playing their part,expected or not. All of thesethemes have been played out,like great social dramas, in thestreets of <strong>Philadelphia</strong>—andthey are still being playedout today…Guideposts, words of inspiration, can come from anywhere—andinside the front cover of his daily planner,Father Paul Washington keeps such words: facts, quotes,dates, statistics about African American buying powerand numbers of African Americans incarcerated, wordsof scripture, names of civil rights martyrs, and more.When he is called on to speak, he is never at a loss,always prepared. Many have depended on Father Washington,over the years, for his readiness, for knowing whatto do, for helping others to find the ethical, just andrighteous position. The words in the front of his planner,and the many dates and appointments inscribed in itspages, are reminders of both the struggle to find theright and ethical way, and the hard daily work of buildinga just society. Formerly rector of the Church of theAdvocate, Father Washington’s planner from 1968includes the dates of the third Black Power Conference,held at the Advocate under his tenure, on August 28through September 1, 1968—a time when “somethingrevolutionary took place there.” The planner also chroniclescountless meetings on many issues of importanceto his parishioners in the North <strong>Philadelphia</strong> neighborhoodof the Advocate, and on local, regional, national andinternational issues.“Reggie Schell came, from the Black Panther Party, andthey wanted to have a rally. And they wanted to use thechurch. And of course, what you knew about the BlackPanther Party, you read in the white press. ‘These arepeople who believe in violence and this and that and theother.’ And I listened very carefully to what the BlackPanthers were saying. They were saying ‘We have a rightto defend ourselves. And if violence is perpetrated on us,we feel justified in defending ourselves by violence.’I always sought for an answer as to ‘Why?’ Why would youdo it? And I wanted to be able to justify my answers theologicallyand biblically. They’re saying they have a rightto self-defense, and by God, I believe they have thatright. People really came for that rally from all over thecountry—10,000 people. And people were afraid thatthere’d be violence. Not a single incidence of violence. Andso they came and went… There are some firsts thattook place there, at the Church of the Advocate.”–Father Paul M. Washington2021