Daphne Park Memorial book 3_3.indd - Somerville College

Daphne Park Memorial book 3_3.indd - Somerville College

Daphne Park Memorial book 3_3.indd - Somerville College

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

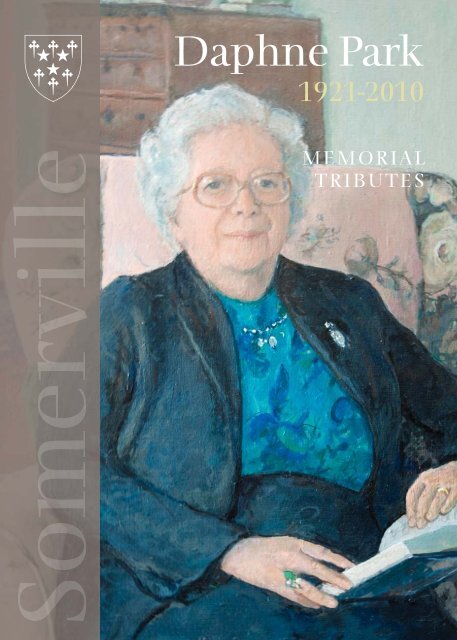

<strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong>1921-2010MEMORIALTRIBUTES2

<strong>Daphne</strong> MargaretSybil Désirée <strong>Park</strong>BARONESS PARK OF MONMOUTHCMG, OBE1 September 1921– 24 March 2010PRINCIPAL OFSOMERVILLE COLLEGEOXFORD 1980-1989<strong>Memorial</strong>Tributes1

ContentsForeword by Dr Alice Prochaska, 3Principal of <strong>Somerville</strong>Funeral address given in <strong>Somerville</strong> 4<strong>College</strong> Chapel on 6 April 2010 byMiss Barbara HarveyAfrican Childhood (from The New Yorker) 11School 15Oxford 1940-43 18War Service 19The Secret Intelligence Service 22Principal of <strong>Somerville</strong>, 1980-89 39House of Lords 53Editors : Pauline Adams and Liz Cooke.The editors wish to acknowledge their great debt to Caroline Alexander(<strong>Somerville</strong>, 1977), author of a Profile of <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong> in The New Yorker,30 January, 1989. This article is quoted with permission throughout the<strong>book</strong>let. <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong> herself left no memoirs.2

Foreword by thePrincipal of <strong>Somerville</strong>DAPHNE PARK is quoted in these pages as believing when she was a school girl “we allreally thought we could conquer the world. It never occurred to us that we couldn’t dowhat we wanted with our lives”. Even as a teenager she was already the sort of person<strong>Somerville</strong> has always tended to produce. In later life, as these recollections show, shebecame the quintessential Somervillian; resourceful, brave, and always curious aboutthe world. She was a great internationalist and also someone who naturally engagedwith people from every sort of background. She was, most especially, a person capableof intense kindness, and someone who shared her sense of fun and enjoyment of lifewith everyone around her. When I wrote to colleagues at <strong>Somerville</strong> (before I arrivedhere as Principal myself) to commiserate on <strong>Daphne</strong>’s death, one of them replied thatyes, it was very sad, but it was also impossible to think of <strong>Daphne</strong> without feeling happy.Few people leave the world with such a strong sense that it is a happier place becauseshe was here. <strong>Daphne</strong> was a unique spirit, as these recollections show. I feel personalsorrow that I did not have a chance to know her better; but also a humbling senseof privilege to serve in succession (at two removes) to someone who made such anenormous contribution, both to the world and to British foreign interests, and to<strong>Somerville</strong> <strong>College</strong>, which played such an important role in shaping her. Living upto <strong>Daphne</strong>’s legacy is a huge challenge, as I remember each time I talk to a <strong>Somerville</strong>student about their lives and aspirations, or hear from someone who was at <strong>Somerville</strong>when she was Principal. The recollections printed here give a flavour of this mostexceptional human being. Those of us who were privileged to know her, even a little,will feel proud and humbled that we did.ALICE PROCHASKA3

Address given by Miss Barbara Harvey at theFuneral of <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong>in the Chapel of <strong>Somerville</strong> <strong>College</strong>, 6 April 2010DAPHNE PARK WAS REMARKABLE in her generation; and since she wished always tobe judged by the highest standards, I will add that my ‘generation’ includes men as well aswomen. The situations which made her a legend in her own lifetime were often complexand dangerous. But her philosophy of life was simple, a matter of three words: ‘Life is fun’.For her, life was fun precisely because it was challenging, and she found deep satisfactionin responding with all her formidable powers. Indeed, she was rather unhappy if the nextchallenge was not in sight; she liked to be ‘flat out’. When, on my last visit to her, justbefore she entered hospital, she said that she was feeling ‘rather bored’, I knew how ill shemust be, for <strong>Daphne</strong> and boredom had always been strangers to each other.4The challenges began to appear when <strong>Daphne</strong> was very young. Until she was nearlyeleven, she lived with her mother who ran, but did not herself own, a coffee plantationin the highlands of what was then Tanganyika though later part of Tanzania. Her fatherpanned for gold some distance away, and <strong>Daphne</strong> and her mother could expect to seehim three or four times a year. Books, however, were sent by relatives in England, andwhen she was old enough to do this, <strong>Daphne</strong> read to her mother, whose reading sighthad failed. <strong>Daphne</strong>’s favourite <strong>book</strong> at this time was Huckleberry Finn, and her favouriteauthor John Buchan, who perhaps implanted in her mind the first seeds of the ideathat a career in Intelligence would be exciting. Her formal education consisted of acorrespondence course run from Dar-es-Salaam by the daughter of the Anglican bishopin Tanganyika, for children in <strong>Daphne</strong>’s situation. But now the decision was made tosend <strong>Daphne</strong> to England, to live with her grandmother and two great-aunts in southLondon and attend the Rosa Bassett School, a state secondary school, in Streatham. Sheowed this life-changing opportunity to her teacher in Dar-es-Salaam, who wrote to hermother to say that such a clever child must go to school. But she owed also a great dealat this point to her mother, whose savings, though not large, provided the money neededfor the journey to England. She travelled in the care of some friends of her parents whowere making this journey. The first part of the journey, to Dar-es-Salaam, included alorry ride, and <strong>Daphne</strong> never forgot the cloud of locusts on the way: there were, sheremembered fifty years later, locusts in your ears, locusts in your eyes, and locusts onyour face. Lack of funds and the 1939-45 War made it impossible for <strong>Daphne</strong> to seeher mother again for fifteen years or her father for an even longer period; her youngerbrother, who died at the age of fourteen, she never saw after leaving Africa.

<strong>Daphne</strong> rarely mentioned her new family, who were now her guardians, but she toldme more than once how on one occasion her grandmother insisted that she walk in thestreets of Clapham, where they lived, wearing the pierrot’s costume she had somehowacquired, and so learn not to be self-conscious. The treatment, if it was needed at all,was evidently successful, for although in adult life <strong>Daphne</strong> possessed a normally wellhidden sensitivity, she was never self-conscious. In later life, she always spoke with greatenthusiasm about the Rosa Bassett School, which encouraged an international outlookand political interests on the part of its pupils, and where the teaching was excellent. Itencouraged pupils who were of this mind to try for Oxford and in 1940 <strong>Daphne</strong> entered<strong>Somerville</strong>, to read French and to be taught by the exacting Enid Starkie. But in theprevious year a scholarship enabling her to spend three months living with a family nearParis had laid the foundations of the fluent French that she later spoke. She thought ofproficiency in languages as a necessary qualification for the diplomat she already hopedto become and was excited by this opportunity. But Oxford and <strong>Somerville</strong> would havebeen impossible had she not won both a state scholarship and a county scholarship.At Oxford, she was active in student politics and served a term as president of theUniversity Liberal Club, an achievement that she perhaps too modestly attributed to thewartime absence of serious male competition.In 1943, with the Final Honour School – in which she took a good Second – in sight, andwar service to follow, <strong>Daphne</strong> and her circle of friends discussed how they could havean interesting war. To <strong>Daphne</strong>, wars were won by people in uniform, and she declinedpositions in both the Treasury and the Foreign Office, prestigious though these offerswere. Eventually, assisted by her potentially useful background in East Africa, shepersuaded the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, better known as FANY, to accept her. In apart of FANY that itself operated as part of the SOE, The Special Operations Executive,she helped to train paramilitary groups, known as the Jedburghs, for action with theFrench Resistance, and in the course of this work she served for a time in North Africa.Her special role was that of codes instructor.<strong>Daphne</strong> entered the Foreign Office and the Secret Intelligence Service [SIS] concurrentlyin 1948. She served for thirty years, and when she resigned in 1979, she had thirty moreyears of active life before her. But 1948 was, I think, the decisive ‘moment’ in her life,and throughout that longer period she remained at heart the public servant she now5

ecame, the servant of a country that she was proud to serve and, as she said, wouldnever knowingly harm.Nevertheless, the course of her career after 1948 was profoundly affected by herexperiences in the immediate post-war years. As a member of the Allied Commissionfor Austria in 1946-8, she engaged in the search for scientists and technicians who hadserved under the Nazi regime, with the purpose of learning what their work had beenand, if possible, preventing their disappearance eastwards into Russia. Subsequently,in her first years in the Foreign Office, she witnessed the disappearance behind the IronCurtain of large numbers of Czechs and Poles, in a tide that could not be stemmed. It wasin these years that she acquired her abhorrence of totalitarian regimes and admirationfor those who lived under them, unwillingly but without sacrificing their own values.They represented ‘invincible humanity’, and she longed to know such people at firsthand. Much later, when looking back over a considerable passage of time on her careerin the SIS, she spoke of her postings in Africa as the most fascinating in her career, andit was through these that she first became widely known. She served in the Congo in1959-61, during the last year of Belgian rule, the Declaration of Independence, and thedescent of the new Republic into civil war. Although she now had many African friends,this was for <strong>Daphne</strong> a time of great personal danger. Later, she served in Zambia,formerly Northern Rhodesia, at the time of the Unilateral Declaration of Independencein what had formerly been Southern Rhodesia. But as a very young diplomat she longedto serve, not in Africa, but in Moscow.She obtained this coveted posting in 1954, having prepared for it by an intensive coursein Russian in Cambridge. She left Moscow two years later with a heightened sense of theevil of the communist regime. Since, however, she was now a Russian speaker, she hadbeen able to travel outside Moscow and its environs on train journeys lasting in somecases eleven or twelve days, and in this way to meet people who were less affected bythat regime than were those at the centre; on such journeys, moreover, surveillance wasmuch less common than at the centre. Later, she recalled among many others to whomshe talked on these journeys ‘a particularly delightful beekeeper from the Ukraine’. Shewould not have neglected to tell him that the native name of the place where her motherrented the land for her farm in Tanganyika meant ‘the place of bees’.6

Some fifteen years later, as consul-general in Hanoi, where the consulate had onlyone other person, and was, indeed not officially recognised by North Vietnam, shewas handicapped by the refusal of the communist regime to allow her to learn theVietnamese language or to travel more than small distances. She took to daily walks,on which she saw much but even so found it difficult to make any personal contactwith those living under the exceptionally harsh regime. It was mainly the politicalcontacts of this posting that made it seem easy to put up with a rat-infested houseand other inconveniences. ‘There had been an extermination programme’, she laterrecalled, ‘but the rats didn’t know about it’. But not even Hanoi shook her belief in‘invincible humanity’. When, in 1978, at her own suggestion, <strong>Daphne</strong> described to me,in my capacity as Vice-Principal of <strong>Somerville</strong>, a little of her work for the SIS, beforea decision was reached whether or not she should be a candidate in our forthcomingelection of a new Principal, she described a focus of interest on those livingunwillingly under totalitarian regimes of the kind that I have tried to describe today.The existence of the SIS was not publicly acknowledged by the government until themid- 1990s, by which time <strong>Daphne</strong> had retired from the Service and, indeed, from herprincipalship of <strong>Somerville</strong>: she was now enjoying a new career as a life peer. It was, ofcourse, widely known long before this date that she had been a member of the Service,which was itself already widely known to exist. Nevertheless, the Panorama programmeon the Service, in 1994, in which she took a major part at the request of the Secretaryof State, meant for her a loss of official anonymity that she found at first very strange.She felt, she said, as though she had lost a skin. But subsequently, her reticence abouther actual work was as strong as ever. Indeed, in conversation she sometimes seemed tothink that the Panorama programme itself could be spirited away. Her extreme reticencewas adopted out of consideration for those who might be harmed by any other courseof action. For the same reason, she never wrote her autobiography, much though shewould like to have done so, and she was contemptuous of others in similar positionswho succumbed to this temptation. We can be sure that the anecdotes that over so manyyears delighted the audiences that heard them, and indeed proved capable of delightingthe same audiences several times over, contained nothing relating to security that wasnot already known.7

Nevertheless, these stories are major sources for <strong>Daphne</strong>’s own life in the Service, and inparticular for her extraordinary courage. Although courage was the quality that she mostadmired in others, she always disclaimed it for herself: for herself she would admit onlythat she was curious and optimistic. But all these attributes are needed to explain whatshe was able to do. Who but an exceptionally courageous person would have entrustedherself to a midnight fishing trip from Stanleyville, in a canoe and with someone whowas to all intents a stranger, in the hopes that after the fishing she would meet membersof the Central Committee of Le Mouvement National Congolais who would form thegovernment when, as was anticipated, Patrice Lumumba came to power? And who buta person of exceptional courage and presence of mind could have turned a menacing,weapon-bearing, African crowd bearing down on her Citroën 2CV into a friendly group,anxious to help, by getting out of her car, greeting them warmly, throwing up the bonnetof the car, and enlisting their help in repairing her carburettor (which as a matter of factwas in perfect working order)?8When, in 1980, <strong>Daphne</strong> became Principal of <strong>Somerville</strong>, she did not leave behind allthe Difficult Places that she included in her entry in Who’s Who as a form of recreation,but the particular ways in which <strong>Somerville</strong> was for a time at least such a place werenew to her. Her own views were carefully formed, and often proved in the event tobe prophetically right for the <strong>College</strong>. It was, however, a new experience for her tofind herself without a defined place in a hierarchy, but only first among equals andpossessing influence but not power. And it was a cause of some amazement to her thatthe fellows of <strong>Somerville</strong> disliked telephone calls when teaching or researching – twoexclusion zones that seemed to cover most of the day – and preferred the written noteas a form of communication. Later, e-mail would solve this problem, but to the end ofher life, <strong>Daphne</strong> never used this method of communication. Because, as she frequentlyreminded us, she came from ‘outside’ and not from an academic context, she found nodifficulty in separating the unparalleled achievement of Margaret Thatcher in becomingPrime Minister from the grievous effects of her Government’s policies on universities.She found the University’s refusal, in 1985, of a proposal to confer an honorary degreeon Mrs Thatcher, and the lack of a significant measure of support for the proposal in<strong>Somerville</strong>, where she was an honorary fellow, incomprehensible. The sadness that shefelt as these events unfolded never quite lifted during the rest of her principalship.

Yet the fact that she was an ‘outsider’ in the sense I have explained, was a huge advantageto the <strong>College</strong> at this juncture in its history. She was quick to identify our needs,great and small; with no previous knowledge of this role, she made herself a highlysuccessful fund-raiser; and as careers for our students in the older professions becamemore and more difficult to get, she worked hard to introduce them to different outletsand especially those existing in industry and commerce. As a cosmopolitan figureherself, and as an emissary for the <strong>Somerville</strong> Appeal, she breathed new life into the<strong>College</strong>’s ties with its alumnae in every part of the world, but especially in the USA. Inthe University, moreover, she played an important role as a member of HebdomadalCouncil and a pro-Vice-Chancellor.Nevertheless, I see our main debt to <strong>Daphne</strong> as something quite different from anythingI have so far mentioned. When she became Principal, in 1980, morale - especially amongthe fellows and graduate students - was rather low, and, in both cases, that mood canbe traced to the fact that in the course of the last few years nearly every college in theUniversity that had previously accepted only men had now begun to accept women aswell, and to accept them at all levels: as undergraduates, graduate students, and fellows.The winds of competition were swirling around <strong>Somerville</strong>, still a college for womenonly, in a new and worrying way. <strong>Daphne</strong> however, was an incorrigible optimist anda highly infectious one. It was rare to meet her even casually without receiving somewarm words of encouragement. I well remember a younger colleague, a historian, as Iam, saying to me one morning: ‘I have just run into the Principal and had my piece ofencouragement for the day.’ It was this optimism, joined to an inspired pragmatism inidentifying the best way forward for the time being, that did so much to keep us togetheras a community, living in amity despite differences of opinion among us on majorissues, and enabled her to lead us through these most difficult years.When, in 1990, <strong>Daphne</strong> received a life-peerage, she entered on what she once calledher fourth career, and it was one of unalloyed pleasure. She loved everything about theHouse of Lords: the formality and courtesy of its proceedings, the occasional pageantry,the importance of its work as a revising chamber for legislation, and other things besidethese. At first, she hesitated to accept the honour when it was offered and felt obligedto tell Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister who had nominated her, that althoughshe wished to take the Conservative whip, she might not always be able to support9

Conservative policies. Having received what she described as a ‘brisk’ encouragementfrom the Prime Minister to differ whenever she wished to, she accepted. And she didindeed run into trouble with the Whips for her strenuous criticism of the government’spolicies towards the universities. Higher Education, and its needs, including studentloans, were her first interest as a life peer and a continuing one. In 2000 she spokeeloquently in a debate on Higher Education, to dispel long-lasting misconceptionsabout Oxford’s admissions policy. But by now her main interests were different andher membership of Committees and Sub-Committees correspondingly onerous. Theinterests included, besides Defence and Foreign Affairs, Northern Ireland, and shespoke on the Northern Ireland Peace Process when she was already seriously ill andonly a few days before entering hospital.I will end by returning to the beginning of <strong>Daphne</strong>’s life peerage. She was moved to tearsby the admission ceremony. At the time, I did not fully understand her emotion, thoughI felt moved myself by the matchless prose forming part of the ceremony. But now thatI have read a piece written by Professor Anna Davies, after <strong>Daphne</strong>’s death, I think I dounderstand, though I shall express the matter rather differently. <strong>Daphne</strong> was movedbecause she felt that she was once again a public servant, able to express her love for hercountry, and to do so now with no need for concealment. She was in her defining roleagain but in the open, where she had perhaps often wished to be in the past.10

African ChildhoodFrom the Profile of <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong> by Caroline Alexander,The New Yorker, 30 January 1989MISS PARK’S FATHER, John Alexander <strong>Park</strong>, while a young man attending Queen’sUniversity, Belfast, had contracted tuberculosis, and his family sent him to South Africafor a “cure” in the healthy climate. Within a very short period of time after his arrival,in 1894, he had given away all the money they had supplied him with. “What exactlyhappened to it I don’t know, but he was fairly shortly working in the mines – perhaps notthe best place for someone with TB” Miss <strong>Park</strong> observed dryly.He later ran a store on the high veldt, then became interested in seeing a bit more of thecountryside, and so walked north through what was then Rhodesia, settling in Nyasaland(now Malawi) in 1905, where he began to grow tobacco. When the First World Warbroke out, he became an Intelligence officer for the Nyasaland Frontier Force, and waseventually wounded and transferred to Roberts Heights, a hospital in South Africa. Hehad come from a scholarly family—his father, who held the Chair of Moral Philosophy atQueen’s University, had spoken Latin, Greek, or Hebrew with him on their Sunday walks—and some years before the war, being lonely for intellectual exchange, had advertised inthe Cape Times for a pen friend “interested in philately and philosophy” and had receiveda reply signed “A.C.G.” During his convalescence, he wrote to his friend saying, “My dearchap, I’ll come over and meet you,” and they arranged to meet in Pietermaritzburg.“I’m not sure at what stage A.C.G. told him that she was a woman—whether he knewbefore he got off the train,” Miss <strong>Park</strong> said. “Anyway, she met him, and she broughtalong her daughter – my mother – who was very beautiful. My father fell in love with thedaughter at first sight, and they were married six months later.” John <strong>Park</strong> was forty-four,and his bride, Doreen Gwynneth Cresswell-George, only nineteen. Her father had cometo South Africa from Britain in order to seek his fortune, the family’s money having beensquandered by his stepfather, who had a fondness for playing the horses.The couple left the tobacco plantation to go to England for the birth of their first child,and <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong> was born in Surrey, on September 1, 1921. Before leaving Africa, herfather had made arrangements with his partner, a defrocked Portuguese priest whomeveryone had warned him against, to see to the drying, insurance, and shipment of hisbumper tobacco crop. The tobacco arrived at its destination musty, totally ruined, anduninsured; <strong>Park</strong> returned to discover that the partner had made off with everything hecould from the plantation. After debts had been paid, nothing remained to <strong>Park</strong> except his11

ifle. Nevertheless, his young wife and their six-month-old baby left England to join him.“We arrived in Beira, on the Mozambique coast,” Miss <strong>Park</strong> said. “They had just builtthe railway to the Zambezi River. We got on the train, but there was a flood, and partof the track had washed away. It was a fairly adventurous journey. We had to crossthe Zambezi, in flood, in a little boat, because the paddle steamer wasn’t working, orperhaps it had sunk…. We then got into a lorry and drove for three days.”Shortly after their arrival, John <strong>Park</strong> walked on to Tanganyika. “It was thought that therewas gold in the Lupa River, so he went off prospecting, and, indeed, he found alluvialgold. So he sent for my mother and me, and we took a boat that went up Lake Nyasa.When we got to the landing place, at Mwaya, my father wasn’t there – he’d miscalculatedthe date of our arrival. We camped for two days on the shore, where I was an object ofsome interest, as I was the first white child ever seen there.” The reunited family thenset out for the Lupa, Doreen <strong>Park</strong> travelling part of the way in a machila, or hammockswung on a pole, and <strong>Daphne</strong> on people’s shoulders. “We walked for about ten days, Ithink, through very wild country, some of it quite beautiful. The Lupa ran through lioncountry – lots of lions, lots of prickly bushes, and very dry, very little water. My parentsbuilt a mud hut, and we lived in it until I was about three. My father made enough frompanning for gold for us to survive, and my mother planted a garden.”Doreen <strong>Park</strong> discovered that she was pregnant again, and undertook the long trekback to England. She bore a small, delicate boy, and returned with him to her family inAfrica. The <strong>Park</strong>s realized that living in such conditions was not going to be good for thechildren, and so decided that while John would continue to pan for gold his wife wouldmove to the highlands and grow coffee. “They rented land at Kayuki, which means ‘theplace of bees,’ and my mother ran the coffee plantation and grew arabica and robusta.She sent food for my father’s laborers – a four-day trip – and my father sent her the gold.It was an astonishingly honest world in those days, and the gold was generally sent byrunner. My father would walk to the farm once every three or four months and stay forseveral days; otherwise, my mother and brother and I lived entirely alone.” The houseon the coffee plantation was built of mud brick, with a roof of thatch and corrugatediron, and it acquired, over the years, a Rubberoid floor and a porcelain bathtub with tapsbut no running water.12

The family’s self-contained life – they were ten miles, or a good day’s walk, from theirnearest European neighbors – affected <strong>Daphne</strong> most markedly in two ways: she wasable to indulge a precocious appetite for <strong>book</strong>s, and she came to rely almost entirelyon her own resources. Her voracious reading as a child was supplemented by acorrespondence course conducted by the Bishop of Tanganyika’s daughter for childrenwho were living in the wilds. Each lesson took about ten days to arrive, being sent bylorry, train, and finally runner; sometimes the <strong>book</strong>s were damp, if the runner hadfallen into a river on the way. “It was wonderful. I read lots of history, lots of Englishliterature. I loved classics, but mathematics was a disaster. The teaching was very good,too – lots of comments. And then there came a day when the correspondence peoplewrote to my mother and said, ‘You’ve got to send this child to school.’ I was almosteleven. So my mother and father conferred, and it was arranged that I would go toEngland with some friends of theirs... In Dar es Salaam, I switched on my first electriclight and pulled my first loo chain. I wasn’t to go back to Africa for years and years.There was no money for me to go back, or for my parents to come to me. My mother’smother and my two great-aunts became my guardians.”“Africa left very little immediate impression on me. Curiously, the first time thatmy memories of Africa came to me with real intensity was much later, when I wasstudying Russian at Cambridge. I had been asked to write an essay on my childhood.It was my first Russian essay, and I had to look up every single word and grammaticalconstruction. Consequently, I wrote with more concentration than I have probablyever written in my life. I found that what I wanted to describe was what I had almostforgotten I had ever been aware of: night sounds, like frogs, crickets, drums; thefingering of the sun when it was really hot; the sound of rain on corrugated-iron roofs.I suddenly realized that it was all there somewhere, at the back of my consciousness.When I eventually went back to Africa, I accepted a lot of things that other peoplefound frightening. It didn’t occur to me to worry about living alone there, for example– it wasn’t a place where I was ever frightened. I loved Africa, but I can also rememberperiods of intense frustration and boredom, because there was no one to talk to.I grew up solitary. I wanted to ask questions, I wanted to sharpen my mind. When Ifirst came to England, the thing I most loved was having my mind sharpened with lotsof new arguments and ideas.”13

SchoolIN HER OWN WORDS:I LOVED SCHOOL. I loved the whole experience of being there... I went to a verygood state girls’ school – the Rosa Bassett School, in South London – where we all reallythought we could conquer the world. It never occurred to us that we couldn’t do whatwe wanted with our lives – that we couldn’t go where we wanted in the world. It wasintensely political. People like the great social reformer Eleanor Rathbone used to comeand talk to us. Our headmistress was very socially active, and the school was always fullof refugees. When the Spanish War happened, there were Basque children, whom sheadopted, and when things got really bad in Germany we had several Jewish refugees,most of whom never saw their parents again. We were very much aware of what washappening in the world. I am an internationalist because of that school.<strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong> in conversation with Caroline Alexander, January 1989RECOLLECTIONS OF SCHOOL-FRIENDS:MY MOST VIVID MEMORY OF DAPHNE was her first appearance in FormLower 2 in the Prep. I think we were about ten. We were all 1930s little girls wearingthe summer uniform frock: light blue cotton with skirts just above the knee, with whiteankle socks and Clarks brown sandals. <strong>Daphne</strong> joined in the middle of the term. Shewore a white lacy knitted dress, very elaborate, with a scalloped hem and petticoatsbeneath, white knee high socks, elaborately patterned, and white leather shoes. Wewere allowed to wear our hair short or in plaits. Hers was long and loose. Probably thiswas what girls wore in the colonies but we were astonished, for we had only seen suchan outfit in a story <strong>book</strong>. We were much too nice to show our astonishment. And shesoon appeared in uniform. She was never uniform herself – always nice, very cleverand assured. She soon moved to the year above us and after that I only rememberher at a school trip to Paris in 1938 and again in Chichester (where the school wasevacuated during the War) in 1939.Peggy Jefferies, née Andrews15

IT WAS OUR FIRST DAY in the Rosa Bassett Grammar School, mid-September 1933.I was still eleven years old, my partner in our double desk just twelve. We had introducedourselves, exclaiming over the fact that we were both named <strong>Daphne</strong> Margaret, although,of course, my partner had two more given names. I noticed that she seemed to be actuallycaressing the sides of our battered desk. Seeing my enquiring glance, she said, “Oh,<strong>Daphne</strong>, it’s so wonderful to be sitting here at last, at a real desk, in a real schoolroom!”Astonished, I asked, “Why, what did you have before you came here?”“Oh, well, you see, I’ve come from Africa. My brother and I had to use a couple ofkerosene tins, with a board across them. And we were outside, in the open air, not in aproper classroom like this.”Every aspect of school life enchanted <strong>Daphne</strong>: she seized on every new experiencewith total energy and commitment. Even in our first game of hockey, when we two verymyopic girls were deprived of our spectacles for fear of breakage, <strong>Daphne</strong> flung herselfwholeheartedly into the game, breathless and happy, playing a real game of hockey, in areal school field, with real schoolgirls, who liked her.For it had not taken us long to realise that, in <strong>Daphne</strong>, we had a prodigy and anornament to our form. Her sweet nature and the obvious joy she felt in being amongus were immediately endearing, and we regarded her with affectionate pride. Andsometimes with awe, as when our form mistress asked us individually, when we werethirteen, what we wanted to do with our lives. <strong>Daphne</strong>’s answer, “I should like to be auniversity lecturer”, reduced us all to dead silence. She must have wondered what shecould have said to cause such unnatural quiet.Popular though she was, <strong>Daphne</strong> had no close friends. She came to us as an adultamong suburban teenage girls. How could we possibly understand such an intellect,conditioned by such a background? She told us almost nothing of her life in Africa: weknew nothing of her heroic struggle to reach the education which we took for granted.My home background was turbulent; <strong>Daphne</strong>, with her intuitive insight, saw that all wasnot well with me, and without obtrusive questioning was gently kind and thoughtful. As Iwas the smallest girl in the school, which led to my being dubbed “Tich”, the Sixth Formcommanded me to play Tiny Tim in the school show “Christmas with the Cratchits”. We16

presented the play, I duly delivered my five words, the curtain fell to a gratifying wave ofapplause; exit the Sixth Formers, leaving me alone on stage and suddenly overwhelmedby a wave of panic. Had I made a complete fool of myself? But there at the exit was dear<strong>Daphne</strong>, waiting for me. She rushed forwards, gathered me up in her arms, swung meround (what a strong girl she was!), kissed me on the cheek, and cried, “Oh Tich, youwere wonderful!” I could have wept for gratitude and relief.Her poverty was only too evident in her school dress. While the rest of us were smart inour neatly-pleated outfits, made of good woollen stuff, <strong>Daphne</strong> wore a gymslip whichmust have seen many owners, was a faded mauve and worn so thin that it would nothold a pleat and fell in shapeless folds. Her personality was such, however, that we soonceased to notice.At the Rosa Bassett, in the first three years, I had taken what I considered my rightfulplace as first in English, <strong>Daphne</strong> coming second. In the end-of-year 5th form exam,however, I was dismayed at the choice of essay titles, none of which stimulated myimagination. I did my best with the least uninspiring, and stood with <strong>Daphne</strong>, facing thenotice-board on which the results were posted. We were both speechless with shock– <strong>Daphne</strong> was first, I was second. It was the only thing which might earn me grudgingpraise from my father, for whom I could do nothing right, and the shock of losing myplace was paralyzing. <strong>Daphne</strong> and I looked at each other in horror – I believe that shewas even more stricken than I was. With that intuition of hers, which amounted totelepathy, she knew how much it meant to me. I can see her now, as she raised her armsslightly, then dropped them helplessly to her sides. “Oh, dear Tich! Dear Tich!” shecried, and turning suddenly on her heel, she left, one hand to her eyes.In the end-of-term bustle, there was no chance for us to speak again together, and as myfamily was leaving London, I was never to see her again. But I do cherish the memoryof the dear girl who once restored my confidence, and shed a tear for me when she hadwounded me, simply by doing her best in an examination.<strong>Daphne</strong> Helsby, née Whittle17

Oxford 1940 - 43IN HER OWN WORDS:I WENT UP TO OXFORD very self-confident. Bear in mind, too, that we were atthe beginning of a war. The very month that I went up, the docks were set ablaze andthe Battle of Britain took place – one was thinking about something much, much biggerthan oneself. People one knew were getting killed. There was a great danger threateningthe country. I don’t think we ever feared that Britain would actually be invaded, but wewell knew that life was dangerous, and the idea removed quite a lot of one’s normalpreoccupations. The war had a marked effect on our generation – it gave us a senseof perspective. And women were playing a considerable part in the war. They weregoing into the services, they were ferrying aircraft, they were in the factories and theambulance service. Women were doing things with men, side by side. I don’t think thatat that time there was any particular need, as a woman, to prove yourself. I was aware,however, that there were some things I was able to do at Oxford because so many of themen weren’t there. For instance, I became the president of the Liberal Club. I believeI was one of the first women to be the president of a university political society, and Ithink, realistically speaking, that if the normal number of young men had been there mychances would have been greatly reduced.”<strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong> in conversation with Caroline Alexander, January 1989IN HILARY TERM 1943 a number of undergraduates volunteered to take part in amock blitz organised by the City Council to test Oxford’s preparedness for an emergency;the Principal was subsequently congratulated by the Town Clerk on the histrionic abilityof one Somervillian “whose realistic impersonation of a hysterical foreigner deprivedof house and sense and all coherent speech had shown up some weak spots in the cityorganisation.” The undergraduate in question was later identified as a modern linguist inher final year, <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong>.Pauline Adams, <strong>Somerville</strong> For Women (OUP, 1996), p.243.18

War ServiceFrom the Profile of <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong> by Caroline Alexander,The New Yorker, 30 January 1989“AT THE END OF OXFORD, everyone went into uniform of some sort, and in myfinal year the civil-service commission came and interviewed all of us. We were verymuch encouraged – on the whole, expected, if we were bright and politically aware – toaccept the appointment offered. I was offered two positions, one in the Foreign Officeand the other in the Treasury – the two top things one could do – but by that time I wasfirmly convinced that the war needed me to win it. I had some idea that I was goingto... I don’t know what exactly, but I was quite sure it would be something directlyrelated to winning the war. I could be a civil servant later, but I was not going to go toWhitehall and push pieces of paper around.”The next wave of recruiting officers came from the various women’s services inthe Army and the Navy. “I was told that I would do interesting things, like being aneducation officer and teaching courses in current affairs... I rejected that, and nothingmuch remained but being called up into industry.” A chance meeting with a formerSomervillian who was also a linguist gave her a new idea of the direction she mighttake. Her friend had joined FANY (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry), a women’s corpsthat had been founded during the Boer War as a nursing unit, but had come to playa variety of roles within the regular services. “My friend said that she was doingsomething intensely dull in Whitehall, but she looked so smug about how dull it wasthat I suspected that it was very interesting.”She and two friends went to the FANY headquarters in London, where they weregreeted with a complete lack of interest and barely succeeded in obtaining aninterview. Ultimately, <strong>Daphne</strong>’s family background in East Africa, where FANY wasactive, distinguished her from the other applicants, and she was told to report to acertain country house.For two weeks, the chosen applicants were marched and drilled and given various teststo determine their potential as wireless operators and codists. At the end of the training,a final examination was administered. “There were two parts, a practical examination,consisting of things to be coded, and a question: ‘Explain why codes are used in timeof war.’ The answer was obviously `So as to communicate without the enemy knowingwhat you are saying.’ But I was straight from Oxford, and I thought, What a veryinteresting question. I started with it, and wrote a long and thoughtful essay, beginning19

with Pythagoras, on the history of coding. I looked up later and discovered, to my horror,that I had something like ten minutes left for the really important part. When the resultsof the examination were made public, I was called before the examiners and told, ‘17838,Volunteer <strong>Park</strong>. We are sorry to say that you are the first person who has managed to failthis exam. We don’t quite know what to do with you.’ ”She was sent to FANY’s headquarters, in London, to work as a mess orderly while herfate was being decided. A disastrous accident involving the service lift, in the middleof a formal dinner in honor of a war hero, insured her quick dismissal from that job,but her superiors told her, with some puzzlement, that she had been asked to reportto the Special Operations unit. “It turned out that someone – as a great joke – had sentmy exam paper to the very man who had invented many of the codes, and he wantedto meet me,” she explained. They did meet, and he put her on his staff. “After that,” shesaid, with an air of smugness no doubt similar to that exhibited by her linguist friend,“I had a very interesting war.”21

The Secret Intelligence Service<strong>Memorial</strong> Address by Sir Gerald Warner, University Church,Oxford, 29 May 2010DAPHNE PARK WAS A REMARKABLE LADY: soldier, intelligence officer,Principal of <strong>Somerville</strong> <strong>College</strong>, and Baroness <strong>Park</strong> of Monmouth. A legend in herown lifetime, yet what was most remarkable was her simple goodness, and the almostuniversal affection and esteem in which she was held. I am here to remember her asan old friend and colleague in the Secret Intelligence Service.<strong>Daphne</strong> was a child of Empire. Love of our country, its history and traditions, whatshe therefore believed we should stand for as a people and as individuals, were whatshaped and drove her life. Her virtues were old fashioned, rooted in a quiet Anglicanfaith: honesty, unselfishness, compassion. They were the bedrock of her personality,and gave it its integrity and strength. Allied to her courage, energy and optimism, theymade her the formidably effective, enchanting person we knew.She was equipped for many callings. Long ago I asked her why she chose the Service.“Oh, John Buchan, you know. When I was very young I read to my Mother. He was ourfavourite author, Richard Hannay was my hero” There are a lot of echoes of Hannay in<strong>Daphne</strong>, yet I suspect that this was only part of the story. She always marched towardsthe sound of the guns.She was fearless in the face of hierarchy, honest whatever the possible cost to herself.Going down from <strong>Somerville</strong> in 1940, she served in the Special Operations Executive,and loved it. Yet on one notable occasion she put her career at risk. In 1943 she wasposted a very special operational command, the Jedburghs, to train officers and agentswho would drop into Europe on D Day in the communications and cipher skills vitalto their security. She became convinced that her boss was not up to the job, and thatthe operation was at risk. Only a young other rank, she asked to see the commandingofficer, Colonel Buckmaster, and told him the officer should be moved. He heard herout, and the officer was replaced. Buckmaster then wanted to give her a commission,which had to be cleared with the FANY, her parent organization. They called herin and told her she had committed a serious breach of discipline which they wereprepared to overlook, provided she undertook never to do the same again. <strong>Daphne</strong>’sinstant response was that that was impossible. Of course she would do it again if it wasnecessary. And of course she won. She was commissioned.22

<strong>Daphne</strong> joined SIS in 1948. It was early days in the Cold War and the Service was makinga difficult transition to new challenges and worldwide responsibilities. Remarkably inthose days young officers entering the Service had no training, except, <strong>Daphne</strong> told me,three days on how to write a report. Yet it was the perceptions and actions of those youngofficers that were largely to shape the future of the Service. They were trail blazers, and<strong>Daphne</strong> was foremost amongst them.Women were entering the foreign office for the first time. Officers of our service hadrarely had diplomatic rank. <strong>Daphne</strong> therefore had to prove herself doubly competent,as a woman and a spy. She always claimed that she rarely felt disadvantaged as a woman,and she was proud of being a spy. Certainly she convinced the Ambassador in Moscowthat she was a great asset and not an embarrassment. Thereafter our presence inEmbassies, even in the Soviet Bloc, was readily accepted, and we who followed her had amuch easier time.Her time in Africa in the 60s was of greater importance. As a Service we had littleexperience of Africa. <strong>Daphne</strong> taught us how to operate there. The little girl who had runbarefoot with her native friends in the hills of Tanganyika was completely at home. Sheunderstood the importance of personal relationships for Africans, empathised with theirwarmth, sociability, and laughter, and knew that people, not paper or policies, were thekey to understanding.In the Congo, in Leopoldville, she set an example of how in times of civil war and turmoilour service could play an important and distinctive role. She survived not least becauseshe was fearless, which the Congolese respected, but also because she could make themlaugh. One of her better stories was of being ordered out of her 2CV by an armed gang.When she refused they tried to pull her out through the roof. She got stuck, and broke into helpless giggles. So did they, and let her proceed.Yet it was in Lusaka that her most significant work was to be done. On arrival in 1964she was told by the High Commissioner she might as well go home for there was nojob for her, and anyway Africa was no place for a woman. Untroubled, she rapidlyestablished many important contacts, especially in the Zambian security apparatus, onwhich the President particularly relied, for she well understood that in Africa influencewas more important than intelligence, and that our service had special opportunities23

to exercise it. Nevertheless much suspicion of the former colonial masters remainedwhich even she would have found difficult to break down, had not something happenedto enable her to prove her good faith. She discovered a plot close to the president ofwhich she might have taken short-term advantage. Instead she took the longer view andthe more straightforward course and told him of it, thereby demonstrating that, againstexpectations, she could be trusted to act honourably even when it was not in the UK’sshort-term interests. It was a crucial example that the British could be trusted. Wordgot about; not only in Zambia, and the ability of our Service to influence events wasaccordingly much enhanced. Those who subsequently worked on African issues felt theyowed an enormous debt to <strong>Daphne</strong>. It was she, they say, who laid the foundations andestablished the ethos for much of what was subsequently achieved.She remained well connected and influential on African affairs for many years. Indeedshe was called in to brief the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, before a crucialCommonwealth Conference in Lusaka. We were told it was a difficult meeting. <strong>Daphne</strong>was told that she would have 10 minutes; in the end she had two hours. As was herwont, the PM led from the front: Lusaka was full of terrorist organizations - FreedomFighters by another name – and therefore President Kaunda himself was a terrorist. ThePM would have no truck with him. <strong>Daphne</strong> suggested that life was not quite like that,and advised a rather more diplomatic approach, with much toing and froing about thecauses of colonial and postcolonial conflict. The PM was unmoved and gave no groundwhatsoever. But at CHOGM and without any acknowledgement in any direction, the PMconducted herself very much as <strong>Daphne</strong> had advised – and indeed earned plaudits inAfrica through a widely circulated photo of Kaunda and herself on the dance floor! Thismeeting began a relationship of mutual respect between two formidable ladies.Since her early career had been shaped by her perception of the Soviet threat and herexperience of the KGB in Austria and the Soviet Union she was happy to return to acommunist country, even though the prospect of Hanoi at the height of the VietnamWar might well have daunted many ladies in their 50s. Her purpose was to be a windowon North Vietnam for both HMG and the Americans. Her reports and dispatcheswere much applauded, especially because she provided unique insights into Sovietthinking – regularly – and Vietnamese - more occasionally. For although <strong>Daphne</strong> loathedcommunism she was perfectly capable of liking and indeed charming the communist.24

Speaking both French and Russian was an advantage. She and the Soviet ambassadorgot on famously, and met regularly to exchange views. The Vietnamese were moredifficult, but <strong>Daphne</strong> contrived to turn a negotiation into a useful series of contacts.The negotiation was about transport. Being rightly suspicious of what she might get upto they refused to allow her a car, or a bicycle. After some months <strong>Daphne</strong> suggesteda trishaw with a member of the security bureau as pedaller. This was accepted, buteventually her sense of mischief went too far. She turned up at the Soviet national daywith a Union Jack on the handlebars. The trishaw was withdrawn.She always made the best of everything. Sir John Moreton, then Ambassador in Saigon,has given me a delightful vignette of <strong>Daphne</strong> at this time. He writes, “<strong>Daphne</strong>’s visitswere like a breath of fresh air. She made light of all her difficulties, radiating optimismand always full of intellectual curiosity. It was a particular pleasure to learn of her plansto hold a Queen’s Birthday Party in war-torn Hanoi, and to be shown the hat and dressbought specially for the occasion. British Birds adorned both hat and dress.” What aprivilege, he says, to have known her.In Hanoi she made her name with the Americans. They appreciated her intellect andthe quality of her commentaries, and warmed to her robust and forceful personality. Onlearning of her passing a former operational head of CIA told me “She was one of thevery best. Not only was she a good friend to us, but she was a feisty lady. She had the raregift of saying hard things without giving offense.” Their respect was reciprocated, so itwas fitting that her last post in the service was as Controller for the Western Hemisphere,and as such our main interlocutor with the CIA. As a Controller she was notable for herforesight. She insisted on providing emergency communications in South America,which proved their worth during the Falklands War. She was also notable (perhaps someOld Somervillians present will relate to this) for “her fierce loyalty to her staff, at timesbordering on the irrational”.I suppose the service was <strong>Daphne</strong>’s first and last love, but <strong>Somerville</strong>, and the Lords,ran us close. If entry into our service was, as Barbara Harvey has suggested, the definingmoment in <strong>Daphne</strong>’s career, admission to the Lords was surely her apotheosis. TheHouse of Lords embodied her love of Britain; it allowed her to continue to be involved ingreat affairs; and to continue to serve. She came to love the place. Sitting, as she liked to25

say, as a conservative cross bencher, she made many friends on both sides, particularlyperhaps amongst the military. All her life she had been a fighter, determined to beat allthat is bad in our world.Indeed, an old and dear friend of <strong>Daphne</strong>’s suggested to me that if one were looking forone word to describe her it would be “gallant”. Never more so than in her last years,when she suffered from arthritis and cancer. She continued to work and to speak in theLords until two months before her death. Then, true to herself to the end, she asked herdoctors to let her go. But to the end also she thought of others. I was with her on her lastafternoon. As I left she said “Good bye dear Gerry” and then, as though to reassure me,“It’s all right you know”.Good-bye dear, gallant, <strong>Daphne</strong>. How much we all loved and admired you.26<strong>Memorial</strong> Address by Sir Mark Allen, St Margaret’s,Westminster, 26 October 2010SHORTLY BEFORE SHE DIED, <strong>Daphne</strong> was giving attention to the order of thisservice. She asked me to say something about what, she often said, was the proudestand gladdest aspect of her life – her time in the Service. She spoke of ‘The Service’rather than ‘The Office’ – as did my generation. And this was because <strong>Daphne</strong> was nobureaucrat. She was greatly impelled by other values, chief among them a dynamicsense of service.<strong>Daphne</strong> was creative and, operationally, she didn’t miss a trick, but her fundamental flairwas generosity.<strong>Daphne</strong>’s generosity of spirit came of confidence. Hers was no defended personality.Happy in her own skin, she was not easily disconcerted. Her commitment to herpurpose was infectious. Her love of her own country could lead others onto a higherplane in their thinking about theirs.I suggested to her, just before she died, that she might think of spending her heavenarranging for confidence to be given to the young. It was a gift she had herself received

in plenty. Her years as a young woman, whether due to, or in spite of, the extraordinarycircumstances of her childhood, were quite simply years of conquest.Earlier in the year, I had received a message that there was some concern about the gunin <strong>Daphne</strong>’s jewellery safe. We had a long lunch and, at the end, I said, ‘I think it’s timeto let go the gun.’ ‘Oh?’ I said that, if she went into hospital and it was discovered, well,this could be awkward. ‘Oh, OK, then.’ The gun wasn’t in the safe; and we searched theflat. I was looking for a large service pistol, possibly with a lanyard. Finally, <strong>Daphne</strong>called out, ‘Got it!’ As she handed it to me, an exquisite, tiny revolver with a pretty inlaidgrip, she said it had been made for her by the armourer of SOE himself.She told me once how she had had to pass a grim and deeply sensitive message to herambassador in Moscow. I asked where she had done this. ‘Oh, it was on the dance floor– I thought we shouldn’t be overheard there and I could keep a good hold of him’.Years of conquest indeed.In the Service, <strong>Daphne</strong> loved its foibles and the human factor. She loved the Service’s– by the standards of our own politically-correct day – spirit of adventure... and also itsgood sense that values and skills are best learned by watching people, rather than bylistening to them. The Service aimed to recruit those who could get this. And may itlong do so.<strong>Daphne</strong> was not short of an instinct for excellence. When in Moscow, she had to receivea delicate briefing and was summoned to West Berlin to hear it. She was told that hercover for the journey was to be a visit to the dentist. And her new controller made hergo to the dentist. This was no parade ground discipline, but his cat-like attention to theimportance of detail. And <strong>Daphne</strong> got the point.That controller was a major figure in <strong>Daphne</strong>’s formation. How she admired him andwas grateful to him. With a distinctively feminine insight, she noticed that his gift forleadership was simply to inspire a determination that we should not let him down. Ithink <strong>Daphne</strong> would allow me to say that it was also the genius and spirit of the Servicewhich helped her become the <strong>Daphne</strong> we remember today.<strong>Daphne</strong> had a strong sense of fairness. Fairness transcends language and culture. Heartspeaks unto heart and engages powerfully with the rational. It makes friends. For27

<strong>Daphne</strong>, this moral dimension of human contact was a fascination, a compass bearing, ademanding standard and even a calling. It made her a powerful operator. And it cannotbe denied that power interested <strong>Daphne</strong> greatly – not by any means for herself, but asthe focus of the Service’s work.She rather tartly explained to a member of the uniformed branch that while he wouldundoubtedly become an ambassador and she would not, he would be consumed by somuch secondary business. She, on the other hand, though thought more lowly, wouldstill be fortunate enough to be dealing with the heart of the matter – the riddles of power.Years later, landing at the centre of a crisis, she had the chance to ask him if this had notproved to be so; and with great grace he gave her a broad smile.In this sense, <strong>Daphne</strong>’s work was vocational: she knew she was made for it; she was verygood at it and grew a great love for it. Consequently, she became a remarkable person.More personal than a heroine, her influence was personal, yet vast.Contrary to much Mandarin belief, the Service depends on the integrity of its staff.The English can recognise integrity but we find it difficult to be articulate about it. Wejust call it by name and esteem it. <strong>Daphne</strong> showed us that her integrity was simple:she integrated her faith and values into her personality and into her behaviour. Shewas what she believed: she was a living value. Her friends could not but think, ‘if allthis matters so much to <strong>Daphne</strong>, why doesn’t it matter like that to me?’ Hence her ownpower of leadership.Thus her own challenges to her friends and colleagues were, of course, formidable. Butthey were challenges to others which were always an encouragement, an encouragementto reach out for what, she could see, was really within their own grasp. It was <strong>Daphne</strong>who first taught me the wisdom that it is pointless to ask someone for what he hasn’tgot to give. It’s no way to make friends. <strong>Daphne</strong> had so many friends because to hereverybody was of interest – she did not recognise the category of ‘ordinary person’.For all these reasons, <strong>Daphne</strong> was an inspirational figure in the Service and greatlyloved in return. On the Service’s very important occasions, three ancestors would bebrought in to represent the generations past. <strong>Daphne</strong>’s controller was one; and shewas another.28

I mentioned <strong>Daphne</strong>’s instructions about this service. She also asked me to read to youthe lines which occurred to Tennyson one evening while setting out on the ferry fromPortsmouth for the Isle of Wight, a landscape so familiar to members of the Service. Onan impulse, Tennyson took a piece of paper from his pocket and, without hesitation oralteration, wrote the following verses.CROSSING THE BARSunset and evening star,And one clear call for me!And may there be no moaning off the bar,When I put out to sea,But such a tide as moving seems asleep,Too full for sound and foam,When that which drew from out the boundless deep,Turns again home.Twilight and evening bell,And after that the dark!And may there be no sadness or farewell,When I embark;For tho’ from out our bourne of Time and PlaceThe flood may bear me far,I hope to see my Pilot face to faceWhen I have crost the bar.29

The following accounts of some of <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong>’sdiplomatic postings are taken from her 1989 interviewwith Caroline Alexander in The New Yorker.THE CONGO, 1959-61:In 1959 <strong>Daphne</strong> received her third foreign posting, as British Consul in Leopoldville.“The Belgians had been talking about independence for the Congo – they knew it wasinevitable, but they were not really sure when it would happen,” she recalled. “Theywere talking about thirty years hence, then five years hence. The Belgian colonialpresence was very unenlightened. The Belgians teaching in the remote parts of thecountry, who were able to speak one or more of the thirty-seven tribal languages, usuallygot on well with the Africans. In Leopoldville, it was much less attractive. The flamandswere frightened; they kept big Doberman pinschers, put grenades under their beds, andhad bright lights in their gardens. By law, servants were sent home at night – for fearthey’d cut their masters’ throats while they slept, I suppose. I did not want to live in theEuropean quarter. I couldn’t see myself making any African friends if they had to passeveryone’s Dobermans to reach me. A house was found for me on the airport road, nearthe Cité Africaine. It was very hot. The houses in the European quarter were up on a littlehill, which at sea level makes a lot of difference.“It looked as if independence might happen rather sooner than thirty years hence, soour consulate general was instructed to get to know the new African parties and theirleaders, if they could be identified, and tell the Foreign Office what they represented.This was not easy. From the Belgian point of view, any gathering of three or moreAfricans presented a threat, and people were not forthcoming. It was difficult to meetAfricans, because the Belgians had no machinery for whites to meet with blacks. Theyhad, however, just started to appoint African mayors for the arrondissements into whichLeopoldville was divided, and when the governor-general wanted to give a party to whichAfricans were invited he called on them. The only other Africans one could readilymeet were the undergraduates at the university. It was not a very representative group;there were twelve graduates, I think, in 1960. My instincts about my house proved to be30

correct: because it was situated between the African quarter and the town, I had manyAfrican visitors daily. As a consequence, I was struck off the governor-general’s invitationlist – which I didn’t mind. I had a few non-Belgian European friends, and I made goodfriends with some young American academics, but most of my friends were black. Myhaving been brought up in Africa must have helped. Also, I was interesting to manyof the African nationalists, because I travelled up and down the coast a lot – to Ghana,Nigeria, and French West Africa. When I first arrived, I used to go to fetch the Embassymail from Accra. Most people liked to do it once or twice but then got bored, whereas Ididn’t mind. One had to cross the river to Brazzaville, then fly to Douala, often gettingstuck in Gabon en route. One would get as far as Lagos, then get stuck again beforereaching Accra. It could take three days. I was meeting and talking with people all theway, so I knew what was in the air.”Slowly, her political contacts built up. Future ministers stopped by her house on theairport road as they commuted to and from Leopoldville, and the evening conversationson her veranda were pursued until the early hours of the morning. She met PatriceLumumba, the leader of the Mouvement National Congolais, by chance in the Britishconsulate when he was standing in a queue for a visa to go to Ghana. Her introduction toother members of the M.N.C. Central Committee was more unorthodox. Before setting outon an official trip to Stanleyville, she asked Lumumba to advise her on how to get in touchwith M.N.C. members, many of whom were based in Stanleyville. Lumumba gave her thename of a certain Monsieur Barlovatz, and told her to look him up when she arrived.“So I met M. Barlovatz and introduced myself and told him what I wanted, and he saidyes, he could arrange for me to meet the committee members. But in the meantimewould I like to go on a little fishing trip? I said I would like that very much. The fishing, itseems, was best at night. We set out in a canoe, in the dark, and we shot the rapids, andwe caught lots of fish, and then we pulled over to a cove where some other fishermenhad built a fire and were cooking their dinner on the coals. And, fortunately, I hadbrought along a bottle of whiskey, and we had a very sociable evening. Finally, we left,and returned to Stanleyville just as it was getting light. And I thanked M. Barlovatz for anenjoyable trip, and I said, ‘Now, remember. You have promised to arrange for me to meetthe members of the M.N.C.’ And he said, ‘Mademoiselle, you just did.’ “31

On June 30, 1960, independence was declared. Lumumba became the Prime Minister inthe new government, which was headed by President Joseph Kasavubu. Less than a weeklater, there was a mutiny of the Force Publique, which was both the national Army andthe gendarmerie. Shortly afterward, the troops of the Thysville garrison, just south ofLeopoldville, seized the poorly guarded munitions stores and roughed up some of theirEuropean officers. Overnight, some six thousand Belgians fled the country.“It was so wasteful and sad. The Belgians were deeply afraid that now, at last, scoreswould be settled. In fact, very few scores were settled, and in Leopoldville almost nothingreally happened. We were roughly treated, but nothing happened. After the mutiny andthe troubles, I got a curfew pass from Lumumba’s office and could go back and forth,but, unfortunately, very few people had these passes, and so very few people could visitme. Everyone around me had left... I lived alone, and I didn’t have a gun or a dog. I didoccasionally get a mild frisson as I walked into the house – I wasn’t totally foolish – but Idaresay I would have got that living alone anywhere.”The mutiny and the intertribal fighting that it unleashed rendered the political situationbeyond the power of the novice government, and in mid-July, at Lumumba’s request,United Nations forces were brought in to try to stabilize the situation. Katanga, thewealthiest of the Congo’s provinces, had seceded from the new republic and was beingruled by a maverick government headed by Moise Tshombe. Lumumba eventually fellinto the hands of his enemies in Katanga and was murdered, the U.N. troops havingallowed his capture and transportation.“The United Nations force had very curious ground rules concerning non-intervention,which caused me to become disillusioned with the United Nations forever,” Miss <strong>Park</strong>continued. “Lumumba himself, while at the height of his power, had been beatingpeople up, kidnapping them in public, setting his thugs on people – all under the nosesof the U.N. The most scandalous thing that I was personally involved in took place upin Stanleyville, Lumumba’s fief. After Lumumba’s arrest, his Deputy Prime Minister,Antoine Gizenga, proclaimed himself in charge and set up headquarters in Stanleyville.The place was in turmoil, and it wasn’t much fun being a European there. I flew up toStanleyville on some fairly routine consular work, and, unknown to me, and unknown toanybody, Bernard Salumu, one of the higher-placed Gizengists, had put out a decree that32

was dated, let’s say, on a Saturday and didn’t appear in the press until Tuesday. It saidthat any foreigners not provided with new identity papers approved by the regime bySaturday night at midnight would be arrested. And, of course, the deadline had alreadypassed, and on the morning I arrived the troops had gone around arresting everybody,dragging them out in their nightclothes in some cases. When I got to the Stanleyvilleairport, we were all beaten and made to squat in the sun with our hands over our headsfor some time, and we were searched and maltreated generally. The French consul’swife found me while I was waiting to be released – she had come to warn me not to gointo town. But I said, ‘Well, as I’m here, I shall go into town – it’s my job.’ In town, herhusband and the British honorary vice-consul were queuing for their documents outsideSalumu’s office, and I joined them in the queue.“We waited and we waited – mothers with their children, people half dressed – inthe sun for the entire day. The U.N. force did nothing to prevent this or to preventGizenga’s troops from occasionally beating up people in line – the troops were fairlydrunk. Finally, it was my turn to enter the office. Now, Salumu was someone I hadoften entertained at my house. To do him justice, he leapt from his chair when he sawme and said, ‘Oh, Mademoiselle, why did you have to come today?’ There was a smallroom behind him which I knew to be stuffed with people who hadn’t been given food orwater, and which had no ventilation, and I asked him if there were any British subjectsin that room and said that if so I wanted to see them and have them let out. He said thathe couldn’t let anyone out, and gave me a great speech about evil colonialists, and soforth, and he swore to me – truthfully, it turned out – that there were no British subjectsin there. He gave me my document, and told me I had to be out of town within twodays. Once I was outside, the Greek procurator-general rushed up to me and said that aBritish subject had been arrested and was being held in the main jail, where everyonewas in a pretty bad way. I asked him to drop me off near the jail, and to notify the Britishauthorities in Leopoldville if I did not return within six hours. When we got to the jail, Iwalked in and said I wanted to see the British subject, whose name I had been given – itwasn’t a very British name, but British subjects come in all different colors and sizes.The guard tried to send me away, but I sat down and said I would wait until I couldtalk to someone in authority. And the guard, foolishly, rushed away—to find somebodybigger and stronger to throw me out, I suppose. Usually, you could be absolutely sure33

that there would be a lot of armed troops standing around and getting in the way, but Isuppose they were all having their tea or joining in the fun outside, because the momenthe went away I saw that no one was around, and so I walked through a door in his officeand found myself in a central courtyard. It was a fairly horrible sight. There were a greatmany people, black and white, with bloody heads and broken limbs. I asked if therewere any British subjects there, and finally I found the chap, and unfortunately – in a way– he turned out to be a Belgian airline pilot who had flown with the R.A.F. during the warand had been entitled to become a British subject at the time, but hadn’t done so. But hehad now decided that being British might be a good thing under the circumstances, asBelgians were very much the public enemy.”The prisoners begged Miss <strong>Park</strong> to notify outside authorities about other people whowere being detained. Back at the prison entrance, she was threatened with arrest, butmade the counterthreat of going to Salumu, whom she now claimed as a close friend.The Greek procurator-general had loyally waited for her, and when she left the prisonthey went together to the U.N. headquarters, where they were told that they could notinterfere with internal politics. Only when she threatened to speak to the world pressdid the U.N. agree to send a representative to the prison to investigate.“They sent a commission of inquiry the next day, and I went along as the interpreter,because none of the U.N. people spoke any French,” she said. “The prisoners hadmeanwhile been cleaned up considerably, because it had been thought that the pressmight be there. Some sort of solution was worked out, whereby the Belgian prisonerswho were prepared to leave the country then and there were to be allowed to go inthe U.N. airplane to Leopoldville. That was the theory. I will never know how manyactually went.”It was for her service in the Congo and her protection of British subjects in this time ofdanger that Miss <strong>Park</strong> was awarded the O.B.E. “I do not have courage, but I do have amixture of curiosity and optimism,” she said of her activities at this time. “I have alwaysfelt that if I could talk to the people involved, and be allowed to treat them as rationalhuman beings, I would be all right. Also, I had come to know so many really bravepeople during the war that I had a model of a certain standard of behavior. I was alsooften trying to protect or negotiate for someone else – and that makes a difference.”34

HANOI, 1969-70If the Congo was the most eventful of the postings in <strong>Daphne</strong> <strong>Park</strong>’s diplomatic career,the most trying was surely her designation as consul-general in Hanoi, from Septemberof 1969 to December of 1970. It was, as she characterizes it, “a curious situation,” inthat Britain, like France, although it maintained a presence in Hanoi, did not recognizeNorth Vietnam. This anomalous state of affairs resulted in part from the failed Genevatalks in the early fifties, when the French and British had decided to stay on inanticipation of free elections that in fact never materialized.“The British bothered to be in Hanoi at all because it was desirable to have people therethrough whom messages could be sent. The Soviet Ambassador, for example, thought itworthwhile to tell me what the Soviet Union thought would happen if the United Statesdid this or that, and I was meant to pass it on.” The consequence of the British de-factorole was that the consular mission was treated by the North Vietnamese as the leastfavored mission, and the members of the mission staff, who numbered only two, wereessentially consigned to the position of nonpersons. Measures were taken to insure thatthey were as isolated as possible.“We weren’t allowed to talk to the Vietnamese, except chosen ones, like the head of thepolice or immigration. We were, however, invited by the other missions to receptions—Polish Military Day, national days, and things like that—to which the Vietnamese Politburoand a certain number of Vietnamese dignitaries were also invited. There one could meetthem, but it rather depended on the mood of the day whether or not one could actuallytalk to them. I used to clink glasses regularly with people like General Giap, who used tosay to me, with a wolfish grin, ‘Bottoms up.’ But it was a long time before any Vietnameseofficials had any real conversation with me. We weren’t allowed to learn Vietnamese—Ihad asked for a teacher and wasn’t allowed to have one. The only people one could talk towere the members of the diplomatic corps. Our movements were very restricted, and wewere given a scanty petrol allowance, so we could not stray far from the mission premises.All the other diplomats were allowed to go for rest and recreation to a place that was ‘inthe hills’—about fifty feet up. We were not allowed to go there. They were allowed to go toHaiphong. We were not. It was an uncomfortable life, and extremely unhealthy. My housewas full of rats. There had been an extermination program, but the rats didn’t know about35

it. Weevils and worms used to come out of the shower. It was the sort of place where onewas apt to get typhoid, although I never got anything—I was very healthy. But then I hadbeen brought up by my mama to boil all water three times. The temperature regularly gotup to a hundred and ten degrees. There was air-conditioning, but it never worked—and, inany case, electricity was in short supply. You just sweltered.“Once a month in turn, one of us had to go to Vientiane and fetch our mail, and we wouldbe gone for a week or four days, depending on the cycle of the International ControlCommission’s airplane, which was an ancient Dakota that used to fly between Hanoi andVientiane. The Vietnamese would play little games with us, like delaying the exit visa untilit was too late to catch the airplane. Shortly after I was posted there, I decided I would dosomething about all this. I put in for my exit visa in the usual way—through our Vietnameseclerk, who had worked for the mission for years and years. He used to go around to thepolice every afternoon to try to collect the visa—and, of course, to make his daily report onus. Once you have lived in a Communist country, you know that someone has to reporton you, and you don’t hold it against the person or feel rancorous about it. Every day, hewould come back and say that the visa wasn’t in yet. In the past, they had been known todeliver it just too late for you to get to the aircraft, so the ride to the airport was alwayshair-raising. The airplane wouldn’t wait; it landed and turned around very fast and tookoff again. This was for very sound reasons: the Pathet Lao were supposed not to fire theirmissiles for certain periods within the air corridor that the plane used, but either theirclocks were wrong or they used to forget, and occasionally it could be a rather dangerousflight. Therefore, the pilot never wasted time on the ground in Hanoi. About three daysbefore I was due to go, I said to our clerk, `Don’t bother with that visa—there’s a Polishreception next week that I’d rather like to go to. If the visa comes through, all well andgood, but if it doesn’t we can put in an application again next month, can’t we?’ The visacame through the next morning. I had to play little games, too—and after a few times theygot the message, and I had no more trouble with my visa. I don’t know if they decided thatit wasn’t worth it or they were genuinely afraid that I was having a better time in Hanoithan they had suspected.“One was necessarily aware of the fact that this was a war-torn country. It was a countrywith very little food, and people were living on the edge of considerable privation. Youcould see a certain number of wounded about. There was one terrible day, an Easter36