Hitting the - Scottish Opera

Hitting the - Scottish Opera

Hitting the - Scottish Opera

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

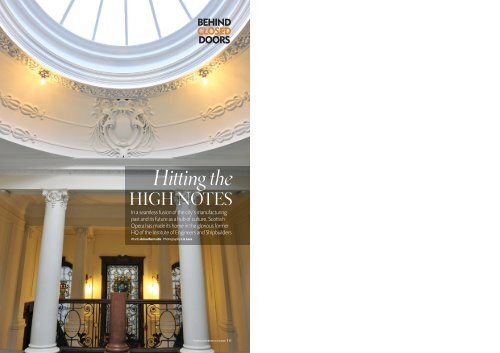

BEHINDCLOSEDDOORS<strong>Hitting</strong> <strong>the</strong>HIGH NOTESIn a seamless fusion of <strong>the</strong> city’s manufacturingpast and its future as a hub of culture, <strong>Scottish</strong><strong>Opera</strong> has made its home in <strong>the</strong> glorious formerHQ of <strong>the</strong> Institute of Engineers and ShipbuildersWords Anna Burnside Photography Liz LeesHOMES & INTERIORS SCOTLAND 111

BEHIND CLOSED DOORSIf <strong>the</strong> ambitious men responsible for <strong>the</strong> magnificen<strong>the</strong>adquarters of <strong>the</strong> Institute of Engineers and Shipbuilders ofScotland at <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> last century were to comeback to Glasgow and see it today, <strong>the</strong>y would be flushed withpride. The street, Elmbank Crescent, may have changed, but<strong>the</strong>ir former home remains as a tribute to its architect, JohnBennie Wilson, and his masters’ attention to detail. The palestone exterior is as imposing as it ever was, <strong>the</strong> Beaux Artsinterior just as lush, and <strong>the</strong> stained glass as intricate andthrilling as when it was installed in 1907.The sign above <strong>the</strong> door might give <strong>the</strong>m a funny turn,though: what exactly is <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> doing in <strong>the</strong>ir venerableold premises?But once <strong>the</strong>y’d taken a look inside, <strong>the</strong>y would be relieved tosee that <strong>the</strong> place has more than stood <strong>the</strong> test of time and thatdetails from <strong>the</strong>ir day, from <strong>the</strong> sliding bolts on <strong>the</strong> doors to<strong>the</strong> fire buckets in <strong>the</strong> entrance hall, are not just fully intact,<strong>the</strong>y are still in use.In fact, <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> has been in <strong>the</strong> building since 1962,when <strong>the</strong> decline of <strong>the</strong> city’s heavy industry forced <strong>the</strong>[Above] Glasgow’s shipbuilding heritage is illustrated in StephenAdam’s wonderful stained glass, along with a portrait of WilliamRankine; [opposite page] <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s musicians and soloistshard at work; double basses take up plenty of spaceengineers and shipbuilders to downsize. Those early days werea bit of a squash, with <strong>Scottish</strong> Ballet sharing <strong>the</strong> premises, andit remained a logistical challenge even after <strong>the</strong> dancers de -camped. The wardrobe department, for example, was splitbetween two floors, <strong>the</strong> sets had to be built in a warehouse inSpringburn, and it was hard work squeezing a timpani into atiny Edwardian lift.Today <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>, by far <strong>the</strong> biggest arts organisation in<strong>the</strong> country, uses all three storeys, plus a vast and largely un -touched basement, for office work and small-scale rehearsals.The company also has a custom-built production unit in anearby industrial estate, where it can manufacture its enor -mous stage sets, store everything from harpsichords anddouble basses to chandeliers, prams, net petticoats and button“IT IS MAGICAL WHEN THE CHORUS OR ORCHESTRA ARE IN. THE MUSICSWEEPS OUT OF THE RANKINE HALL, AT THE TOP, AND DOWN THE STAIRS”boots, and even replicate <strong>the</strong> stage at Glasgow’s Theatre Royalfor full-scale rehearsals. It’s <strong>the</strong> best of both worlds, giving<strong>the</strong>m an impressive administrative base and a functional homefor <strong>the</strong> business-end of <strong>the</strong>ir operation.Morna Gourlay, <strong>the</strong> company’s administrative assistant, hasbecome Elmbank Crescent’s unofficial curator. She clearlyadores every corner of her workplace. “It’s so robust,” she says.“I love <strong>the</strong> fact that it’s still standing and fully functional wheno<strong>the</strong>r buildings we remember from our childhood are fallingdown. And it is magical when <strong>the</strong> chorus or <strong>the</strong> orchestra arein. They are rehearsing Handel’s Orlando at <strong>the</strong> moment and itsweeps out of <strong>the</strong> Rankine Hall, at <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> building, anddown <strong>the</strong> stairs.”The musicians are put through <strong>the</strong>ir paces in <strong>the</strong> grandmeeting rooms where <strong>the</strong> engineers and shipbuilders oncedebated <strong>the</strong> finer points of industrial design. On <strong>the</strong> top floor<strong>the</strong> meeting hall, named after <strong>the</strong> institute’s first president,Professor William Macquorn Rankine, still has <strong>the</strong> originalgold lettering, brass handles and finger plates on <strong>the</strong> doors.The good professor himself stares down from <strong>the</strong> stained-glasswindow, through an impressive set of hand-painted muttonchopwhiskers, on <strong>the</strong> rehearsals below.The o<strong>the</strong>r windows celebrate <strong>the</strong> achievements of <strong>the</strong> insti -tute’s members: <strong>the</strong> Clyde-built liner Lusitania; Comet, <strong>the</strong>112 HOMES & INTERIORS SCOTLANDHOMES & INTERIORS SCOTLAND 113

[This page] <strong>Opera</strong>s are not just about<strong>the</strong> music – <strong>the</strong> costumes and setsplay a leading role too. Dozens ofpairs of shoes and countless wigs arenecessary for each production, alongwith hand-made outfits for <strong>the</strong> chorusand <strong>the</strong> soloists. Transcribing <strong>the</strong>scores is time-consuming work too.[Opposite] <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> has had itsown dedicated orchestra since 1980THE MUSICIANS REHEARSE IN THE GRANDMEETING ROOMS WHERE THE ENGINEERSONCE DEBATED INDUSTRIAL DESIGNfirst commercial steam ship; and Stevenson’s Rocket, <strong>the</strong> firstmodern locomotive. Stephen Adam, <strong>the</strong> Glasgow stained-glassartist, was <strong>the</strong> finest practitioner in <strong>the</strong> country at <strong>the</strong> time,and <strong>the</strong> building is a testament to his talents and versatility.Outside <strong>the</strong> Rankine Hall, under <strong>the</strong> ornate cupola, <strong>the</strong>re is acontemporary brown lea<strong>the</strong>r sofa and several distinctly non-Edwardian chairs. One of <strong>the</strong> problems of fitting <strong>the</strong> 45-oddstaff of a modern arts organisation into a century-old buildingis that <strong>the</strong> ample square footage is often arranged in <strong>the</strong> mostinconvenient ways. While <strong>the</strong> public spaces are generous, someof <strong>the</strong> offices are minuscule, so staff are encouraged to spill outand use <strong>the</strong> hallways as much as possible.With a judicious use of imagination, partition walls andwireless technology, <strong>the</strong>y make it work and opera, <strong>the</strong> highestof <strong>the</strong> arts, is conceived in a building that was built to celebrate<strong>the</strong> industrial revolution. Staff pass <strong>the</strong> crests of <strong>the</strong> westcoast’s great shipbuilding districts – Govan, Partick, Clyde -bank, Port Glasgow – as <strong>the</strong>y climb <strong>the</strong> marble stairs everymorning. It is an extraordinary, poignant fusion of <strong>the</strong> city’smanufacturing past and its future as a hub of culture.A mile or so north, just off <strong>the</strong> M8, <strong>the</strong> production unitcould not feel more different from Elmbank Crescent. It has acafé selling scones and cappuccinos. The air smells of sawdustand fresh paint. What it lacks in stained glass, cupolas andsteam trains it more than makes up for in 21st-centuryfacilities.Staging an opera is a huge technical undertaking and this is <strong>the</strong>company’s factory, where <strong>the</strong> substance of each production is 114 HOMES & INTERIORS SCOTLAND HOMES & INTERIORS SCOTLAND 115

BEHIND CLOSED DOORS[Above] The impressive stone façade was built in 1907 by John BennieWilson; [left] <strong>the</strong> original fire buckets are just some of <strong>the</strong> details thathave been retained – and which are still being used by <strong>the</strong> occupantsTHE LONG SEWING STUDIO ISDOTTED WITH MASKS, BONNETSAND ROLLS OF PEA-GREEN LUREXmanufactured. “The raw material comes in to <strong>the</strong> south car park,and complete operas go out into <strong>the</strong> north car park,” explainsDouglas McGill, who runs <strong>the</strong> production unit. It’s true: as hespeaks, guys in hoodies load <strong>the</strong> set of Dr Ferret’s Bad MedicineShow into a pantechnicon in front of McGill’s watchful eyes.This is where <strong>the</strong> industrial and <strong>the</strong> artistic meet: <strong>the</strong>re areforklift trucks to carry heavy scenery and flight cases, atallescope (that’s a tall ladder mounted on a wheeled scaffol -ding rig) for putting up lights, and a heavy-duty laundry fordyeing, spraying and fumigating costumes. But <strong>the</strong>re are alsowhole storage cages full of period chairs, a row of differentchandeliers and, in <strong>the</strong> props room, a shelf of bottles thatwould put a student crash-pad to shame. All empty. And witha preponderance of champagne. “Somehow, in opera,” saysMcGill, “it is always champagne.”The wardrobe department, which was split between twofloors in Elmbank Crescent, finally has room to brea<strong>the</strong>.Several of <strong>the</strong> company’s most outré creations are dotted likesculptures around <strong>the</strong> building, as <strong>the</strong>y should be – <strong>the</strong>se aretoo fabulous to keep in a cupboard. The long sewing studio isdotted with masks, bonnets, rolls of pea-green lurex andvarious works in process. A plastic laundry basket is filled withstetsons; o<strong>the</strong>r boxes are labelled ‘peasant shawls’, ‘berets’,‘sewing machine manuals’. Two cutting rooms are hung withpaper patterns, one room for men, one for women. There is acosy kitchen area in <strong>the</strong> corner. They need it: in <strong>the</strong> run-up toa production, <strong>the</strong> costume-makers can pull some scary shifts.The costume store, which runs <strong>the</strong> length of <strong>the</strong> building,makes Mr Ben’s cartoon emporium look like a Cowdenbeathcharity shop. There are gowns Marie Antoinette might con -sider a little over <strong>the</strong> top, corsets in every colour, a whole rowof military jackets, a flesh-coloured body suit covered in luridtattoos, a pair of glossy black wings made from real fea<strong>the</strong>rs.Here, as in every department, <strong>the</strong> attention to detail is mindbending.The engineers of <strong>the</strong> Edwardian era might notrecognise <strong>the</strong> end product, but <strong>the</strong>y would surely raise <strong>the</strong>irhats to <strong>the</strong> love and care that goes into <strong>the</strong> process. www.scottishopera.org.uk116 HOMES & INTERIORS SCOTLAND